The Dog Hair Blankets of The Coast Salish People #65

Jo Andrews

Textiles have always been at heart of our culture and history, more so than we have ever been prepared to admit. For thousands of years the Coast Salish people of the Pacific North West, which straddles the border between Canada and the United States, made unique ceremonial blankets and robes from dog hair. Their woolly dogs long pre-dated contact with European colonisers and were specially bred for their lustrous coats. The coverings, which were woven or twined on looms, hold great meaning for the Coast Salish people and are at the centre of their sense of identity, and even though the dog hair is no longer available, blankets are still an important part of ceremonies.

Hooky Mats and Rag Rugs: How the Art of Necessity Helped Define a Nation #64

Jo Andrews

Hooked rugs are humble things made of recycled cloth and worn out textiles, originally born of need and lack: and yet they have come to mean much more to the communities that produced and enjoyed them. In America they became an emblem of homespun pioneer thrift and self-reliance and an important element in the definition of a certain kind of national values.

The Intelligence of the Hands and The Creative Brain #63

Jo Andrews

If you were asked to stitch a picture of your brain what would it look like? A project that looks at the connection between our hands and our brains asked people to do just that. It was aiming to measure creativity and to find out what impact skill and experience has on our actions. These are difficult questions to answer, but this episode of Haptic & Hue looks at what happens to us when we learn activities like knitting, sewing and weaving: how do our hands and brains work together, and which guides the other?

The Mysteries of The Marshes: Ancient Textile Secrets of Europe’s Bog Bodies #62

Jo Andrews

If we need proof that textiles can rewrite human history, then it lies with the bog bodies of northern Europe. Textile archaeologists are revealing a whole new past about people who, in some cases, are older than Tutankhamen, but much less celebrated. Across northern Europe there are hundreds of bog bodies, who long ago were buried in marshlands and were preserved down the centuries by acidic conditions and lack of oxygen. We will never know all their secrets, but slowly we are discovering more about who they were, and how they lived. It is their textiles that bring us closer to them and tell us, not just about their skills, but also how they thought and designed cloth and clothing.

Reviving Rocking Stitch and Saving Whole Cloth Quilting #61

Jo Andrews

Here’s a surprise: an extra episode of Haptic & Hue. We said we were taking a break for July and August and yes, we are. But we thought we would give you a taste of what Friends of Haptic & Hue sounds like and invite you to join the other podcast that we make every month.

So here is the episode of Travels with Textiles that was first broadcast in May this year just as UNESCO announced that it was adding an old quilting practice to the list of crafts that have Intangible Cultural Heritage Status.

The Witches of Scotland: How A New Tartan Became a Living Memorial #60

Jo Andrews

A very special tartan has just started to roll off the weaving looms of the Prickly Thistle Mill in the north of Scotland. This brand-new design in black, pink, red and grey is part of a powerful campaign to remember the thousands of overwhelmingly female lives lost to accusations of witchcraft between the 1500s and the mid 1700s. This was one of the bloodiest miscarriages of justice Scotland has ever seen. Records suggest that at the time Scotland accused and executed more people than any other country in the world.

Textile Waste and the Catastrophe At Kantamanto Episode #59

Jo Andrews

Early this year there was a catastrophic fire at the world’s biggest market for selling and upcycling second-hand clothes. Kantamanto market, in Ghana’s capital Accra, was accidently set alight, and most of the small stalls in the retail part of the huge market burnt to the ground. Two people died, many were injured, and the livelihoods of thousands of people were destroyed, driving many of them into debt and desperation. But the impact of the fire spread much further than that.

Coupons for Clothes: A Wartime Idea Made New? Episode #58

Jo Andrews

Creativity and invention aren’t words often associated with hardship and suffering, but in the Second World War, women in many different countries, including America, Britain, Canada, and Australia faced with clothes rationing rose to the challenge in many different ways.

Those days are long past, but in an era of textile super-abundance, clothes coupons may well have something new to teach us about how we buy and use our clothes. Can clothes rationing cure us of an addiction to fast fashion and help solve the environmental crisis that it is causing?

Pleats Please: The Story of The World’s Oldest Fashion Technique : Episode #57

Jo Andrews

There’s a fashion technique that’s been in continuous use for over five thousand years – proof, if proof is needed, that there is nothing really new in fashion. We have tunics that survive from the time of the Pharaohs in Egypt that use it and you can see it still in the catwalk collections of today.

The Quilts That Hold The Heart of Hawai’i: Episode #56

Jo Andrews

What happens when one of the most traditional museums in the world decides to revolutionise the way it presents the story of the past? The answer is not only a riot of craft and colour, but a reminder of the crucial role of textiles in framing our cultures.

Tapestries for Troubled Times: Episode #55

Jo Andrews

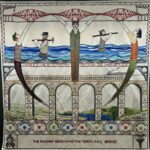

The stitches of the Bayeux Tapestry fix the story of the Norman Conquest of England in our imaginations in an extraordinarily charismatic way. But nearly a thousand years later modern stitchers are picking up their needles to reframe their stories in just as powerful a fashion, showing that textiles can rewrite our histories.

Images from Haptic and Hue’s seventh season of podcasts