Episode #57

Jo Andrews

It’s incredible to think that the simple pleat has pleased the human eye for so long and in so many different ways. Pleating adds movement and life to garments and often signals wealth and abundance. Each culture has found its own way to use them, from the stitched smocks of early English farm workers to the glorious billowing dress Marilyn Munroe wore above the subway grating in the 1950s.

This episode tells the story of the pleats on the world’s oldest surviving woven garment, hears from an expert modern pleater in New York, and tries to unravel the mystery behind one of the world’s most famous pleated garments.

Notes:

The Petrie Museum is just off Russell Square in London. It is free to visit. There are a number of things for those of us interested in textiles, including the Tarkan dress. Watch out too for the earliest known representation of a weaving loom on a piece of pottery.

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums-collections/petrie-museum-egyptian-and-sudanese-archaeology

You can also find the Museum on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/petriemuseum

Tom’s Sons International Pleating is at https://internationalpleating.com/ . They are also on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/internationalpleating/ Where you can get completely mesmerised by watching them pleat incredibly complicated patterns.

George’s Book is called: Pleating: Fundamentals for Fashion & Design and it is in the Haptic & Hue US bookshop and the Haptic & Hue UK Bookshop

Rachel Elspeth Gross is a Fashion Historian. You can find her on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/rachel.elspeth.gross/ or find out more at her website: https://www.rachelelspethgross.com/

Leann Kanda is a behavioural and population biologist at Ithaca college. https://www.ithaca.edu/faculty/lkanda. Her wonderful article about her nine year project to recreate Fortuny like pleats can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03612112.2024.2312021#d1e85 I hope you enjoy it as much as I did!

Anna Garnett, Curator of the Petrie Museum

The Excavation Site at Tarkan 1913. Courtesy of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology, UCL

Original Photograph of the Excavation at Tarkan, 1913, Courtesy of the Petrie Museum, UCL

Tarkan dress showing Pleats. Picture Courtesy of the Petrie Museum, UCL

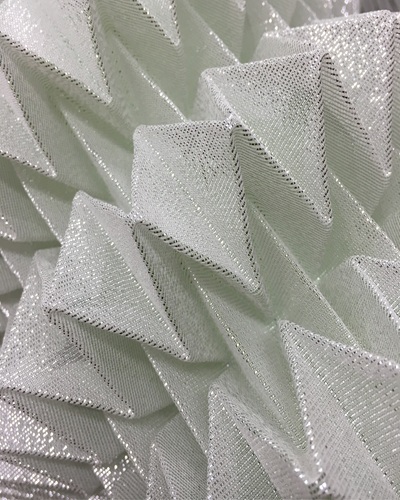

Some of the Intricate Pleats Created by Tom’s Sons. Picture Courtesy of Tom’s Sons

Fantasy Pleat Tom’s Sons. Picture Courtesy of Tom’s Sons

Fantasy Sunburst Pleating. Picture Courtesy of Tom’s Sons

George and Leon Kalajian. Pleating at Tom’s Sons in New York

Tom’s Sons Sunburst Pleated American Flag

Zebra Pleating. Picture Courtesy of Tom’s Sons New York

Rachel Elspeth Gross

Henriette Negrin – Painted by Mariano Fortuny, 1915

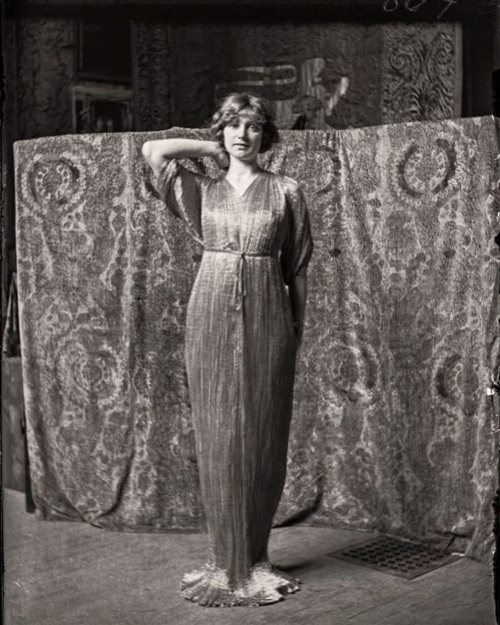

Henriette Negrin Wearing an Early Version of the Delphos Dress

Leanne Kanda’s Recreation named Daphne, with Fortuny like Pleats and Ripples.

Leann Kanda’s Recreated Pleated Dress after Fortuny – Beautifully Pleated and Rippled

One of Leann’s Dresses Properly Stored in a Box to Preserve The Pleats

Script

Pleats Please: The Story of the World’s Oldest Fashion Technique

JA: Welcome to the new episode of Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles – I’m Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver interested in thinking about how textiles and fibre change what we know about the human story. For too long this information has been overlooked and often ignored in the formal accounts of our communities and nations. And whatever else is going on in your life, I hope you find the podcast a calm space in which to hear stories that change the way you see history, because, it seems to me that being able to understand the past in a better way, helps each one of us find a clearer path through the present and the future.

It’s incredible to think that there is a fashion technique that we can say with confidence has been in continuous use for over five thousand years. Put an ancient Egyptian in the front row of a fashion show today and they would marvel at the colour and the abundance of the fabrics on display but they would nod knowingly at the use of pleats which has comes down the millennia from them to us. It seems pleats please us all:

Rachel Elspeth Gross: I feel like there’s just something elegant and something magical about a pleat. It’s like a place where fashion and life and math all kind of like the coalesce. I I just think it’s magic <laugh>. People sometimes write fashion off. We as a culture can look at clothing that is expensive and say its luxury, it’s decadence, it’s excess, and it can be all of those things for sure. But clothing also tells us about what its wearer likes, loves, fears, worries about. I mean, all of that’s in our clothing. And if you are adding pleats for any gender, any type of garment, you’re adding like a kind of gravitas. You’re giving movement, but it’s hidden, it’s sleek. They’re just fun.

JA: That’s Rachel Elspeth Gross a fashion historian, and we will hear from her again as she has been looking at a very important set of pleats and their creator, but first we travel to a small and little-known museum in London. The Petrie Museum is free to visit, its tucked away in the centre of the city and it has some real treasures in it including the Tarkan Dress.

Anna Garnett: We know now thanks to scientific analysis that the dress is the world’s oldest known most complete woven garment. So, we know that it’s over 5,000 years old to be precise. It’s been radiocarbon dated to between 3,482 and 3,102 BC with a 95% accuracy.

JA: Anna Garnett is the Curator of the Museum.

Anna: So, the pleating is sort of all over the bodice and down the, the sleeves and while there’s some debate over how the pleating was produced, the strongest argument is that it’s a type of knife pleating. So, a hot metal knife type object would’ve been used to pleat the material which is a technique that’s still used today. So this is, you know, many thousands of years ago, this is a technique that you know, really produced such a beautiful end product in this garment.

JA: It is a miracle in many ways that the Tarkan dress survived at all and was then identified as a garment. It was found in 1913 at a dig being run by the man who is known as the father of Egyptian archaeology, Professor Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie to give him his full name and title.

Anna: And it was excavated by Flinders Petrie and his Egyptian workforces as part of, so it goes, a very, very large muddy bundle of textiles. So, this bundle was at some point it had been turfed out of an elite burial at the site of Tarkan which is one of Egypt’s oldest and most important cemeteries. And, the Tarkan dress, as we know it today, was excavated as a very muddy, apparently absolutely stinky, bundle of textiles along with many other textiles just bundled up.

JA: Flinders Petrie didn’t really know what this bundle was and interestingly he didn’t try to find out:

Anna: So, Flinders Petrie, he had an approach that was incredibly innovative at the time. So, he is known to have kept small objects or strange objects, something that he just didn’t know what the function of them was, because he believed that someone in the future would’ve developed the scientific analysis and the knowledge to be able to study that material and to find out more. And so, the Tarkan textiles are really testament to that approach. So, Petrie retained these textiles in a very stinky, muddy bundle. They were exported to London to what was then the UCL Egyptian Museum. And ultimately, they lay in wait during the period of the Second World War, right up until the 1970s when they were essentially re excavated in the museum.

JA: Two textile experts, Rosalind Janssen and Sheila Landi, set about incredibly difficult task of prizing the dress from the mud – not at that stage really knowing what they had.

Anna: I don’t know if we have a, an old garment in our wardrobe from 50 years ago. I have a dress of my grandmother’s it’s well made, but of course, the textile is old and fragile. So, we take good care of it. We’re talking about textiles that are 5,000 years old. So, Rosalind Janssen worked closely with the Victoria and Albert Museum’s conservation labs, and a wonderful conservator called Sheila Landi. Their dedicated work over several years meant that this muddy bundle of textiles was sort of re excavated and conserved really beautifully to reveal these internationally important textiles.

JA: And what they discovered was that incredibly this garment showed clear signs of having being worn, it was inside out and had other signs of wear.

Anna: Yeah, so it was found inside out. And we know that because when this muddy bundle was kind of excavated this was noted by Rosalind Janssen and, and Sheila Landi. So, the garment itself would’ve been worn by someone and then taken off, turned inside out and placed in the tomb. And we don’t know if it was deliberately turned inside out for the burial. We’re not sure about that, or whether it was just the case that someone had worn it, turned it inside out, and it was not turned right side out before it was put into the burial. I think it’s quite telling that so firstly we know that someone at least tried it on to turn it inside out, but there are also traces of use wear that Rosalind Janssen noted. So, these are in particular creases on the elbows, but by all accounts, there’s also slight staining under the armpits. So, this is 5,000 year old wear of this textile.

JA: Who knew that even after more than five thousand years, sweat stains under the armpits persist. It makes the Egyptians – who we are accustomed to think of as gods, queens, kings – seem that much more human. Anna says we will never know who the dress was made for, when you see it, it looks small and its true the Egyptians were smaller than us – their diet wasn’t so good. She has her own dreams about the original owner:

Anna: I’d like to think it was worn by a child or a teenager, and partly because there’s so little evidence for childhood in the archaeological record in ancient Egypt. Often a lot of what we know about children is through their parents and how they’re, shown with their parents and, and part of their family. But those sorts of material traces of childhood in, in the archaeological record are largely absent. So, for me, and this is, you know, this is really just me daydreaming here. There’s no evidence for this, but I, I would like to think that what we’re looking at is something that was worn and enjoyed by a child 5,000 years ago. That would be very nice.

JA: It seems from the beginning of time people have tried to give that extra dimension to their clothes. We have surviving fabric from the Iron Age that uses spin patterning to produce a 3D semi pleated effect, this is where yarns are tightly spun in different directions and then woven together. Also, a form of weaving known as barred damask can produce a ribbed effect. But if you want to know about folding fabric then the man you need is George Kalajian – he comes from a big family of Lebanese, Syrian, New York pleaters and he has written the definitive book called Pleating – Fundamentals for Fashion Design – published last year.

George: So, if you boil it down, there’s only three ways to fold a piece of fabric. Okay. there’s an accordion pleat, a side pleat, and a box pleat. Okay. And there’s only two shapes of pleating, which is straight pleating or sunburst pleating. Basically, straight pleating – the lines are all parallel, and sunburst pleating, the lines are all emanating from a centre point. And if you take those combinations and mix them together, you get basically eight classic styles of pleating. The dividing point between these types of pleating is, can something be done on a machine or can it be done in a mould? And usually if something is very small, you know, smaller than, let’s just say seven millimetres, six millimetres, usually it’s in the domain, of a machine. And if it’s something where the lines are not necessarily parallel to each other than it is in the domain of a mould.

JA: George runs a company called Tom’s Sons’ International Pleating in New York’s Garment District and they are contract pleaters to anyone and everyone who needs a pleat:

George: The moulds are just made of cardboard, and they’re scored and they’re folded over and over again and broken into to be able to flatten and contract flat on a table with a positive and a negative.

Jo: And you fit the fabric to the mould?

George: Correct. So, we basically stretch the mould so that it’s as flat as possible. We place the fabric inside of the mould, and then we put a cover on it, and then we contract it, or I should say we condense it together so that it’s collapses. And then we bind it and we put it in a giant steam cabinet, we say we cook it. And it, it basically permanently sets the pleating or permanent is a relative term, but as permanent as possible.

JA: George’s grandmother first taught herself the art of pleating back in Syria, and George says her hands were like gold – she kept the technique of what she did completely secret only passing it behind locked doors to his father Leon. Although in time his entire family became involved in the business. It’s something that makes watching red carpet events with his family a very different experience, it’s not the dresses they are looking at, but the quality of the pleats.

George: I can’t tell who did it often, but I can definitely tell whether they knew what they were doing. <Laugh>, <laugh>.

Jo: So, can you can look at a dress and go, God, that’s terrible.

George: Oh, totally, totally, totally, totally. I mean, that’s actually how I was raised, when I was a child, you know, my father and my mother or my uncles, they would go to all the big department stores here in New York, and they would look at the, the garments in the window, and there would be very big names in the window. And they would say, that’s, I’m not gonna say any names. That’s huh. Look at that seam. Why did they put it there? What? Those people don’t know what they’re doing over there. Can’t anyone see this? So, you know, when I was a child, I would hear all of this like, nit-picking and not really realizing I wasn’t paying attention. I would say consciously I wasn’t paying attention. But it wasn’t until like, I would say 20 years later, that I realized how much I learned when I was a child, just by being in the room and being in the environment and hearing people, no, no, move it again. Do it again. Or you have to do it this way. So, you know, I’m a big proponent of people starting very early, and especially family businesses. I mean, literally like me, I started when I was apparently seven years old. It wasn’t like my father gave me a punch card and I had to log in my hours. You know, I mean, you come to work with your, with your mother and father, and you have to help them, you know, and son, come here, put your hand here one second. No, don’t hold it like that, son. Hold it like this. And, you know, by doing this over and over through the years, I was learning, you know, I was learning and I was contributing to the family, you know, to the survival of the family. I didn’t realize it back then, but now I realize.

JA: The result is that everyone who wants a difficult pleat comes to Tom’s Sons:

George: All of the local high-end designers come to us. We do have a lot of international designers that come to us usually when it’s something that can’t be done by someone else locally or closer to them. We’re kind of known for doing things that defy the laws of physics. And the Metropolitan Museum has come to us, a lot of people that need to restore garments come to us when they want it to be done meticulously, as close as possible to actually restoring the garment. And also, just regular home sewers that have a passion for sewing. I mean, we do not exclude anyone who wants to experience what it means to work with a professional pleater.

JA: That means that no matter how small their budget Tom’s Son’s Pleaters will help them get the perfect pleat. George has also carried out some incredibly demanding pleats:

George: There was one project, which doesn’t seem very exciting to think about, but it was just an incredibly long pleat. It was 14 feet long, the pleats. And when you get to that l length, you know, it’s very difficult to draw a straight line. You know, you take for granted, you grab a ruler, a little ruler, and then you draw a straight line and you do them parallel, and it looks fine. But when you’re doing it 14 feet long it’s really hard to find something that is that straight. I was finding like long steel beams, but they would flex, they were flexible, you know. And so you would draw the line and literally one eighth of an inch, a quarter of an inch, this giant piece of metal would be bending. So, doing that particular project was very, very enlightening. And required me to really dig deep into the physics of like, what’s happening. You know, as you start to grow, you start to look more at the minutiae, the smaller details than the bigger details.

JA: For George nothing really replaces a pleat on a garment.

George: What is unique to pleating that something else cannot do is volume. You know, it has a way of collapsing a tremendous amount of volume in a very neat in a very neat, systematic way. And it creates a lot of drama by exposing that volume. You know, I mean, it allows, from a comfort perspective, it allows more movement. But in my opinion, the thing that really makes pleading beautiful is seeing the movement of the pleats and deep pleats. And what I mean when I say deep pleats is that pleating that consumes a lot of fabric is just, for me, it’s so beautiful to, to look at, you know, the most simplest, straight, deep pleat hanging on a hanger doesn’t look exciting. But when it’s moving, I mean, for me, it’s, it’s just so much beautiful movement that I love it.

JA: And yes, he does have a couple of favourite pleated garments:

George: So here’s what I feel about that. I fall in love with many garments, and then till the next one comes along, because, we’re always making something new. But I will say this, two of my favourite garments were the dresses worn by Marilyn Monroe. So, you have the iconic subway dress, and you have the gold dress. And if you think about it, I remember I saw a website one time, and it talked about the 10 most iconic dresses in the world. And the top three were the Audrey Hepburn dress, and then the other two were the two Marilyn Monroe dresses. So the top two of the top three most iconic dresses in the world were pleated. So that should say something about pleats.

JA: There is another 20th century dress that is also iconic and it too was pleated, but this one wasn’t made for Hollywood, instead it was made in Venice. Early in the 20th century Mariano Fortuny registered a patent for a rippled and pleated fabric that would make up a long, free flowing and revealing garment – called the Delphos dress. Fortuny was an extraordinary man – an artist, inventor and a fashion designer, who worked from a palazzo in Venice. The dress that Fortuny launched in 1907 came hot on the heels of an era in which women had dressed in bustles and been trussed up in corsets with pinched in waists: unsurprisingly it caused a storm.

Rachel Elspeth Gross: It was a very strange time to have the imperial kind of the world coming to an end, having the religious world start to become less religious. Having women talking publicly about not wanting to wear certain types of undergarments. Even the bicycle, right? Like, so the bicycle’s 1870 something, I think. But, you can’t ride a bicycle side saddle, right? So, the first bicycle dresses were like wide cut culottes, they’re large pants. But we can’t say that that would be scandalous. And the idea that within 30 years you don’t have to wear a bra, let alone a corset. I mean, there’s no panty lines because it’s loose. I mean, it is scandalous. If you think about 1907 and you know, someone who’s dancing on stage, showing their shoulders, you know, I mean it’s, we, it’s hard to be as scandalous right now. It’s, it probably was, you know, a century back. People thought of it as dangerous. I mean, religious leaders preached against it. It was going to make you sick. Your kids were going to be deformed. I mean, all kinds of social problems because you happen to have shoulders, <laugh> wanted to show your ankles.

JA Rachel Elspeth Gross – the fashion historian – says when Fortuny’s Delphos Dress came out it felt exotic.

Rachel Elspeth Gross. I mean, the end of the Victorian, the beginning of the Edwardian, the way that people treated clothing and the way that they interacted with their wardrobes is so different than what we do right now. I think when the Delphos gown came out, people referred to it as a tea dress because it had the implications of informality, even though the hemline was like seven inches too long to actually be a tea dress. But it had that decadence, the silk, it had the mystery that comes from these incredibly fine pleats. It felt new. And I think that there’s an exoticism to the ancients that has intrigued, civilized in quotes, you know, people for as long as we’ve been considering our history.

JA: To begin with only a few women had the courage to wear it.

Rachel Elspeth Gross: People who wanted and were able to afford to shock in public, I think often of the modern dance movement, which was at the same time was coming out. So we’re talking Isadora Duncan and all of her dancers, her adoptive daughters. I mean, ballet as a formal dance has been forever. But the idea of modern dance, of what eventually becomes like jazz and musical theatre and all of the variations and all of those things, these women wearing these dresses at this time we’re able to introduce the world to movement in a way that we hadn’t thought of as appropriate for women or even allowed women to do. I mean, you think of all the formal dancing you’ll see in a period piece, and it’s all very compact. It’s all very refined. It’s all very exact. And when you can spread your arms, when you can spin, there’s a liberty that comes, I think.

JA: Over time the Delphos dress became incredibly successful, thousands were made, in different styles. People came to love, wear and collect them They became Fortuny’s signature item. The dresses now sell for thousands of dollars apiece and most fashion and textile museums hold a number of them. The dresses now sell for thousands of dollars apiece and most fashion and textile museums hold a number of them. After Mariano Fortuny died in 1949, his widow decided the day of the Fortuny dress was over and production ceased. But the folds of these lovely dresses still hold a number of mysteries. The first is the secret of the pleats, which never leaked from the little waterfront factory in Venice, and the second puzzle is who invented the pleating process and designed the dresses? It has always been attributed to Mariano Fortuny, but Rachel Elspeth Gross says there’s good evidence that it was in fact his lifetime partner and wife Henriette Negrin.

Rachel Elspeth Gross: Well, it’s actually, Mariano never said it was Mariano’s. That’s one of the parts of this whole story that just like makes me nuts. And I copied the exact language from the patent and it says, this patent is the property of Madam Henriette Bressard, but that’s her mother’s maiden name, who is the inventor. Like it’s written in his handwriting on the patents for the pleating machine to make the Delphos gown. And there’s a few theories, a few reasons that people think this. One is that women may not have been able, even if it wasn’t officially illegal, it just may not have been allowed for women to get patents in their own name. And if they were able to do so, was it going to take a whole heck of a lot longer? Was it going to be a bigger, more invasive process? And patents are interesting because on the one hand, you really want to protect what you’ve created. On the other hand, you don’t want to make public how you’ve done what you’ve done. So, there’s this dance between exactly enough information to say, Hey, this is mine, but also keep it, it hidden, which is why people say, we still don’t know, you know, how they did this, how they made these pleats, but it’s his, I mean, he wrote down it was her <laugh>. So, it’s, hard for me to take anyone else’s thoughts about that.

JA: The patents that were filed were for the undulating silk and for the dress design, but neither patent described exactly how they made the pleats, and yet we know that Henriette Negrin had all the skills to do this.

Rachel Elspeth Gross: She was like a designer, yes, but she was also an engineer. And she had been working with dyes, like textile dyes for so long. In many ways. She was a scientist. I mean maybe like a citizen scientist by today’s, , view. But there are so many photographs that he took of her working like at a work bench. Sleeves rolled up like, you can see her in the moment. You can see her thinking and you can see her working it out. And I don’t think that the kind of person who could see their partner through that lens and wants that to be the picture, you know, like of course he wrote her name down in the patent. Of course, he gives her credit. It’s a very interesting dynamic that the person who we might villainize in another context for taking, taking responsibility, taking credit, all of that. Like he did all of the things you’re supposed to do, but the world doesn’t remember, even though he’s yelling.

JA: So even if the Museums and reference books ignored her, Rachel Elspeth believes Mariano himself tried his best to give her credit – but the era worked against her and in the end it is his name – Fortuny – that is remembered – just as we remember Christian Dior, Yves St Laurent or the other big designers rather than the people who work with them. Nonetheless Rachel Elspeth says Henriette has achieved a kind of immortality:

Rachel Elspeth Gross: She did work under his label, right? Fortuny is the brand. And so that probably has something to do with that confusion. I mean, I don’t know. Without having, you know, her, her words. I think we’re always going to be surmising, guessing. But it’s fun to do that. And it’s neat to see that in a time and a place when women were not encouraged to work, that she could effectively make herself immortal, right? Like it’s a hundred years later, 200 years later and 50 years, and my kid’s going to college and she’ll know her name, my daughter will remember.

JA: Which leaves us with the mystery of the pleats. And to understand a bit more about that we need to go to a small town in upstate New York to consult an Associate Professor of Biology at Ithaca College who likes dressing up.

Leann:Ecology and sewing have both been part of my life as long as I can remember. I was one of those kids that was, the little nature scientist. I had my microscope. I ran around in the woods. I learned small mammal taxidermy when I was 10. Biology has always been part of me, but so is sewing. My mom taught me how to sew very early on how to make clothes and how to do hand embroidery. And, you know, that stuck with me. Did a lot of costumes for theatre in high school. Did it in college just as a, a volunteer in the costume shop. And that’s where I learned to do things like drafting. And so then, you know, that sort of love of, of sewing has just stayed with me. And I, I do a lot of fancy dress. So, I live in a small college town and nobody dresses up for anything. And so back oh, I mean, this is now over 10 years ago, my group of friends decided like, well, you know what? We want to dress up. So, our New Year’s party, it’s going to be black tie. And me being me, I was like, oh, this gives me the opportunity to make an evening gown, because why else would I ever get to do so?

JA: Leann Kanda does nothing by halves as you can probably tell, the next thing that happened was that she bought herself a Delphos dress.

Leann: And I’d been watching one of these very, very high- priced vintage auctioneers, just so that I could see the, the dresses that were coming through. And there was this small miracle of one that was put up for sale that was very badly damaged and therefore was much less expensive than the other ones that were being offered. So I, I bought it knowing that I could never wear it, the entire upper shoulder, all the pleats are, are ripped. There’s a very bad stain on it, but it got my hands on one.

JA: Just so she could see how it’s made, and hers is one of the versions made in the 1930s.

Leann: it’s that sort of like slightly greenish blue. And it is sleeveless with a basic boat neck. And the shoulders are actually gathered and sewn which is what most of the later Fortuny dresses, how they were constructed. And, and from there, it’s just, you know, the open arm hole and straight sheath down. Pretty much all of the Fortuny dresses are really, they’re just tubes <laugh>. I don’t know if you ever had one of those Halloween costumes as a kid, where you, you just take a trash bag and cut some holes, right? That’s actually, that’s the Fortuny dress. <Laugh>. That’s the Delphos. It’s just that because it’s very finely pleated, it then forms itself to your body much more and looks elegant instead of like a trash bag.

JA I’m not sure that’s what Henriette Negrin had in mind – but trash bag or no trash bag Leann wanted a Delphos dress of her own that she could wear to the New Year Party.

Leann: It started with just seeing a Delphos dress and wanting one, and having enough confidence in my own sewing ability to be like, well, I can be able to create something somehow that will get me there. I just need to learn how to pleat <laugh>. And by the time I was, starting this, there’s quite a bit of, mostly through the internet but, you know, a lot of popular repetition about the Delphos dress and the Delphos pleats with very, very, very little information. But the, the kinds of things that were being said was like, it is very hard to permanently pleat silk and over and over again. Nobody knows how they made the pleats, and then they just full stop <laugh>. Well, why don’t we try some pleat techniques and find out what gets you something that’s like, why don’t we try it?

JA: Leann wasn’t joking, she started a proper scientific experiment. The first thing she tried was a shibori technique from Japan of making pleats by wrapping them around a pole. It made pretty good pleats but they wouldn’t last by themselves and no-one wants a saggy bottom on their Fortuny dress. She tried a number of other approaches including a sort of alkaline perm, but she had a eureka moment when she realised that she needed pressure and a high temperature to set the pleats properly. Her lab had just the thing:

Leann: We have what we refer to as an autoclave but they’re also called steam sterilizers. They’re big pressure chambers that get filled with steam and heated so that liquid water in there can go well above a hundred degrees, goes to about 120 C. And that’s why it’s able to, to sterilize equipment. But I also thought maybe would give me a non-scorched but robust pleat.

JA: That was a major step forward: the autoclave delivered a great permanent pleat. And the added bonus was that her colleagues didn’t seem to mind.

Leann: My colleagues are wonderful. They just laughed at me <laugh>. They were very good sports. And yeah, the, the only thing is actually that, that very first blue piece that I just showed you, I dyed it before I did the pleating, and I did find out that I have to be very careful about having dye and then putting it in the autoclave that the dye ran all over. Luckily, I had set it in a tray, so, there’s still one of our autoclave trays floating around the, the lab room that is stained blue <laugh>.

JA: Leann’s next problem now was to scale up the production so that there was enough pleated fabric for a dress. She had to buy a big pressure canner and take it home to save the science lab’s autoclave. And finally, after nine years of trial and error she came up with a process of pleating that she felt did justice to the Delphos Dress.

Leann: The final technique that really gets the proper Fortuny pleat is not using the arriyo shabori, but actually hand basting threads and then pulling the, the pleats by, by pulling the silk along the baste threads, the key being that you have to do it under tension so that when you’re pulling that fabric along the threads and there’s tension lengthwise. And so, as it collapses on the one thread and collapses on the next thread, it forms a nice straight pleat line between them. Once that hank is created of it concertinered, and then you can tie off the threads and it will hold it in a, a narrow strip, then it goes through the pressure cooking process.

JA: Leanne has written about her precise process and anyone can download her paper and try it out for themselves, the link is on our website at www.hapticandhue.com. She has now made 7 dresses out of her beautiful pleated silk and to my eye they look like pretty perfect and yes, she says it was definitely worth nearly ten years of work.

Leann: Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah. And also one, one of the things, especially now that I have a bunch of them that I can feel more comfortable wearing them, it’s like, well, if I, if I mess this thing up wearing it, it’s fine. Now that I think is one of the reasons why they were so appealing, like for, for people who, once they had them, that they wanted to wear them over and over and over again, they’re so comfortable, so comfortable. I, there’s zero restriction, right? It just beautifully lays against you and that’s it. And it’s like you’re wearing nothing at all, but you’re perfectly concealed. And it, it feels so good. <Laugh>.

JA: A dress is never just a dress – it carries with it its own stories and messages, so the next time you look at a pleat remember how ancient it is – it whispers of pharaohs and film stars, it can tell you how it travelled across Iron Age Europe and lodged in the kilts of Scotland, how it formed the chitons of ancient Greece and the skirts of China’s Song dynasty before it was recreated in the soft silk pleats of Fortuny in Venice.

Thank you to everyone who took part in this podcast for their long experience and understanding of the world of pleats and in Leanne’s case her for extraordinary determination to recreate the right kind of pleat. You can see pictures of her dresses and of the other pleated garments we have spoken about in this episode on our website at www.hapticandhue.com .

Haptic and Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews. It is edited and produced by Bill Taylor and this episode was sound edited by Charles Lomas of Darkroom Productions. Haptic and Hue is an independent podcast free of ads and sponsorship supported entirely by its listeners, who generously fund us through Buy Me a Coffee or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. Friends get access to an extra podcast a month hosted by me and Bill Taylor and in the next episode of Friends we will be talking to Professor Andrew Groves at the unique Westminster Men’s Archive about the different functions the clothing of men and women perform and the way in which men think about their garments. To join Friends go to www.hapticandhue.com/join. But until then its good bye from me and enjoy whatever you are making.