Episode #56

Jo Andrews

The Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford, in the UK, has just added 15 brand new, intensely colourful Hawaiian quilts to its collection of extraordinary artefacts. These skilfully stitched quilts were specially made for the Museum, which holds more than half a million precious objects from all over the world and from all periods of human existence.

Quilting is a craft that over two hundred years Hawaiians have made very much their own – although it was first brought to the islands by incomers. They have developed a unique style that embeds the deep beliefs and rituals of Hawaiian life and keeps them alive in the designing, making and gifting of these beautiful quilts.

Notes:

All the Quilts are on show in an exhibition called Hawaii: From Ma’uka to Ma’kai, Quilting the Hawaiian Landscape, at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, you can find out more here. https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/event/hawaii

Commons Threads Press has published a wonderful book about the quilts edited by Dr Marenka Thompson Odlum called Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands which you can buy here: https://www.commonthreadspress.co.uk/products/mauka-to-makai-hawaiian-quilts-and-the-ecology-of-the-islands We will be giving away several copies of this book with the next Friends of Haptic & Hue.

Dr Marenka Thompson Odlum is on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/lucianmagpie/

You can find the Poakalani Quilters at https://poakalani.net/

Cissy Serrao is on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/poakalani/

Pat Gorelangton is also on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/hawaiianquiltsbypat/

The traditional Hula chanting or Oli that you hear in the podcast is licensed from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. It comes from a recording called Sounds of Power in Time and you can hear the voice of Mary Kawana Pukui.

Marenka Thompson Odlum

The Pitt Rivers Museum

Nai’i or Dolphins, Quilted by Mie Tashiro, Designed by John Serrao

Na Mea Ali’i Wahine, Quilted by Nobuko Nakagawa, Designed by John Serrao

Kalo (Taro), Quilted by Kimi Kumagai, Designed by John Serrao

‘Ulu or Breadfruit, Quilted by Tomoko Kato, Designed by John Serrao

Manu Palekaiko or Bird of Paradise, Quilted by Takako Jenkins, Designed by John Serrao

Honu or Turtle, Quilted by Yoko Nakayama, Designed by John Serrao

O’hia Lehua, Quilted by Susie Sugi, Designed by John Serrao

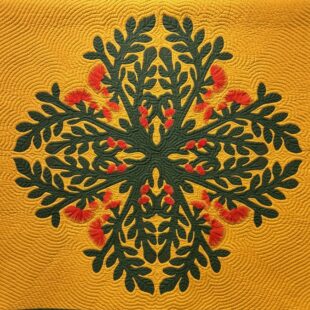

Ti Leaf and Laua’e Fern, Quilted by Pat Gorelangton, Designed by John Serrao

Cissy Serrao

Pat Gorelangton

Catherine Imaikalani Ulep

Script

The Quilts That Hold the Heart of Hawaii

JA: On a dark winter’s afternoon the brown cases of the dimly lit museum in Oxford are stuffed with object after object. The Pitt Rivers Museum organises its objects by type, rather than by time or region, in a system it calls a democracy of things. but as everything takes on a sort of sepia tone in the crowded cases – it’s hard to imagine anything further removed from the pellucid light and warm air of the Hawaiian Islands.

But in a small modern gallery off to the side of the main hall you will find that Hawaii has come to Oxford to lend just a little of its light and joy, and also to show us that textiles don’t just change the way we frame our histories, they also have the power to keep our stories fresh – living things rather than the stuff of memory and the past:

Marenka Thompson Odlum: And, you know, one of the things I always say about the Pitt Rivers, it’s great in many ways, but also gives people the idea that either a lot of these cultural groups are dead, dying or stuck in like a, like a dragonfly in amber. And I wanted to show that that is not the case, that, you know, these are thriving communities. They are, you know, they are still working towards, you know, kind of reclaiming a lot of their cultural heritage, but also changing it and growing.

JA: Marenka Thompson Odlum commissioned these new quilts for the Pitt Rivers Museum and curated the exhibition that they are now part of. I’m jo Andrews – a handweaver and the host of Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles. This episode is about how Hawaiians are using their unique style of quilting to keep alive and to cherish their traditions and their understanding of the ecology and environment of their islands. It’s also about the place new work has in museums at a time when the many of the objects they hold are often understandably deeply contested.

Marenka: I think this is what this entire exhibition kind of represents. It’s the family, the traditional family and quilting, but also the idea of the, the Hawaiian environment being your family, your ‘Ohana as well, and not separating the two. And so, the idea of you being stewards of the land as well. So, if, if we go to the kalo or taro quilt, I think that really brings together the other side of this exhibition that looks about Hawaiian ecology as kind of your family really well.

JA: Hawaiian quilts are immediately recognisable and very different from other quilting traditions, these are not patchwork or pieced quilts but instead appliqued quilts. They are designed in a balanced repeating pattern just as you would a snowflake. Pat Gorelangton has been making Hawaiian quilts for nearly 20 years:

Pat Gorelangton: Well, <laugh>, first of all, you have to imagine what it’s going to be like being interpreted from an eighth of a pattern, which is how the pattern is designed and cut on both the paper that you design the pattern on, and then you place it on your fabric, which has been folded into eighths, like you would make a paper snowflake, that we all learn how to do that in school, you know?

JA: But doing this on a large scale is not easy:

Pat: The cutting is hard because it’s physically, you have to cut through eight layers. And depending on the complexity of the design, you’re going to be cutting tiny little points or valleys or flowers or whatever and then comes opening the pattern, and you need a large space for it. So, I do it on my living room floor. And if you’re making a king size, you’re talking about 108 by 108 inches. And my husband, God bless him, has put sliders under all our furniture. So, I can slide everything to the side <laugh>, but then you’re opening it, and it’s a, a very important part of Hawaiian quilting is symmetry. So, when you open the, or unfold the eighths into a quarter, then a half, and you have to make every effort to have each portion, each eighth as symmetrical to the other in its placement. So, that all eight look as pleasing to the eye as, as balanced as possible.

JA: The motifs are sewn onto a background and the quilt Pat made for the Pitt Rivers exhibition is called Ti Leaf and Laua’e Fern – both plants native to Hawaii’. It’s an incredibly intricate pattern of leaves and fronds on an oxblood red background.

Pat: Well for the Laua’e fern, it is all over the islands and, and it’s used whether, whether it’s in people’s yards or as shrubbery around a hotel or something. And I just, I’ve used it in many of the quilts I’ve made. I just think it’s a beautiful shape. And then the Ti leaf plant is so much a part of Hawaiian culture, whether we make Hawaiian hula skirts out of it, or we serve food in it, especially in the old days to, to serve a portion of food wrapped up in it or served on top of a Ti leaf. They use a Ti leaf when they’re blessing a building here or commemorating something, they’ll have like holy water, but they’ll dip the Ti leaf into it and then spread it that way to sprinkle around the grounds and, and the people who are there, we even will take a Ti leaf and shred it down the length of it and then weave it into a lei and wear it that way. So, the Ti leaf is, is very much involved in the past culture of Hawaiian islands as well as the present.

JA: As Pat says the Ti leaf is very much associated with the Hawaiian practice of Hula or dance But as Marenka discovered, the old customs of Hawaii are having to give way to new environmental pressures.

Marenka: You know Hula is not just dance, it’s a form of communication. It’s a form of storytelling. It’s through that dance. You tell the story of how to care for your land. It’s not only through the dance, but through the cultural practices associated with hula. So for example, a hula practitioner will go up into the mountains to pick the Ti leaf and that, that specific fern but they won’t pick any of it on their way up into the mountains. They’ll only pick it on the way back down. And the idea is on your way up, you see what is growing, how much is left. So, then you know how much it’s okay to take. So, you don’t over pick, And so, in that way you’re being mindful and you’re leaving enough to kind of regrow and repro and propagate the land. You know, so it’s also about sustainability and land stewardship, right? Today, hula practitioners have to change these practices because, for example, Ohia Lehua plant is being threatened by a new fungal disease called rapid Ohia Lehua death. And it is literally like decimating like thousands of acres of lehua forest. And so, one of the things you do is when you come out of the forest, now you actually have to clean your shoes off. So, like all these forest trails, they have these little wash stations to clean your boots. The whole idea is you’re not taking the fungus from one place to the other. So, when hula practitioners go in now they used to, you would take the ferns and the Ti leaf and create what you wanted, and then you’d return those back to the forest to decay, right? You’re giving it back. But because you don’t want to now transmit for fungal disease, for example, you will not do that. You’ll maybe leave it into your backyard to the decay instead of bringing it back into a, a Lehua forest kind of idea. And so, they’re having to change their practices <laugh> to fit the current situation. And that is what you’re seeing in that quilt as well.

JA: And it is what lies behind the quilts, why they were made and who for, that makes each Hawaiian quilt important. Here’s Pat

Pat: The story behind the quilt is just as important as the quilt pattern itself. And there are so many different stories that are the reason for a quilt coming into being. Whether it’s just you have found a colour of fabric that just grabs you or, or far more meaningful, I guess you would say. You want to commemorate a certain event, like a wedding or a birth, or you just see a flower or a, a tree or anything that you want, you want to express it, and you want to be able to show it. But there’s, there’s so much more, the Hawaiian word for it is mana, MANA, and it means the spirit, the energy. And we feel that because Hawaiian quilting is all by hand, we feel that it’s your mana, your spirit, your energy is passing through to the quilt, which will then get passed on to the recipient or the person who asked for it, or and it’s, it’s, it’s a very, it, I don’t mean to sound like it’s a a religious thing, but it’s a spiritual thing, and it certainly means a lot to me.

JA And there is a tradition that to truly pass on your power you add a little more of yourself to a finished piece

Pat: Once you complete a quilt, you sleep under it for a night. So that, that even more of the mana is passed on. And nowadays, I usually just take a nap or <laugh> you know, something maybe a little bit shorter, but it, it, it because you’re doing it by hand, you’re thinking of the person you’re making it for. You’re contemplating how maybe you might wanna embellish it just a bit to highlight the design in some way, but there’s so much more meaning behind it.

JA: One of the most important quilt designs for Hawaiians is of the Kalo and yes there is one in the Pitt Rivers commission, it’s a glorious lime green on a mauve background: Marenka talked about its significance as we stood in front of it.

Marenka: So here we have a quilt called Kalo. Kalo is a Hawaiian name for taro, which is a root crop. It is arguably the most important kind of staple crop in in Hawaiian life. You pound it to make poi. I’m not a huge fan of poi, but don’t tell anybody that <laugh>. What I really love about this quilt is that it depicts the whole plant but also uses the chicken foot stitch at the end as an applique stitch. It creates a whole other dimension to the quilt as well. But the story of Kalo or, or taro, is also just really important because it’s called the older brother, older sibling of the Hawaiian people. And because in kind of the creation myth in Hawaiian cosmology is that the these two, the sky father, earth mother gave birth to a son who was still born. And so, they planted their foetus and that foetus grew into the taro plant. And then the second child was a human being and was then fed from the taro. And so, the idea is that the taro nourishes the people and you take care of the taro as you take over care of your sibling. It’s that kind of symbiotic relationship and that is how, you know, for generations on Hawaiian Islands they kind of fostered the growth of taro as the idea of, you take care of me and I will take care of you.

JA: And the more you look at these complex designs the more you see in them:

Marenka: I just realized that when you look at it, you think it’s four different pieces, but then you realize they’re all connected. They’re not connected by the taro leaves or plants, but they’re connected by the Hawaiian utensils to pound the taro. So, we call them poi pounders, which are usually made of volcanic rock. So, as you can see here, these two leaves are connected by a poi pounder, the same here and all across. So yeah, it’s really, really intricate and detailed and I don’t think I could have done that. It’s also worth mentioning that every single stitch you see is hand stitched. Yeah. So, there’s no machine stitching in the Poakalani group.

JA: All 15 quilts created for the Pitt Rivers Museum were made by members of the Poakalani Quilting Group which is based in Hawaii. Neither it, nor the quilts in the Museum, would exist without a Honolulu policeman called John Serrao and his wife, Poakalani. When John retired from the police in the 1970s he started to create Hawaiian snowflake designs. He turned out to be a genius at it, but perhaps it wasn’t all that surprising as both John and Poakalani had quilting in their blood.

Cissy: My family came from quilters. My mom’s family were quilters. My dad’s family were quilters. When they got married, eventually it was like, okay, guess what, you know. And my mom, it was her passion. She loved quilting. She always talks about watching her grandma, you know, she was not raised by her mom. She was raised by her grandma. And she said, oh, I used to sit underneath the horse and watch the women quilt. And she just loved it.

JA: That’s Cissy Serrao – John and Poakalani’s daughter – who with her sister, Rae, now run the Poakalani Quilting School named after their mother. And the reason their father John began designing was because his wife was born with just one hand and although she had inherited more than 200 hundred historic Hawaiian patterns from her family and she loved quilting she wasn’t able to execute them, until John came up with the idea of making the patterns smaller and allowing her to create cushions.

Cissy: And so yeah, she became the cushion lady. My dad, what he did was he made the pattern smaller for her. She had more control when she put it on the hoop. And what he did was he eventually made a special frame for her. It was squared. Everybody had round hoops back there. But he made a square frame and they put the cushion top at the centre and then they stretched it through Elastic. And she was able to quilt that way. She was amazing.

JA: John’s designs for his wife were so good that word got out and others wanted him to design for them and this is the thing about Hawaiian quilting – it’s not a static regulated thing: here’s the true pattern, it’s an ever changing, flowing art that tells different stories:

Cissy: So, when my dad started designing, the women said, we don’t want what’s in the barrel. We don’t want the old patterns. We want to do our own patterns. And they actually said, John, I know you can do it. You made cushion patterns, you can make the large ones that he started. And so, if you came to him, he still kept in tradition of cutting it out in one piece. But he would always tell the quilter, what’s your story? What do you want to pass on? The tradition is in the Hawaiian quilt, but let’s pass on your story. And some of the designs that he made for these women that reflected their family life and their kids is quite amazing to hear. Some people made a breadfruit and they would put the names of all their kids or their grandkids onto that quilt, and they would just say, my husband loves the ocean. In fact, he is known as the first to actually put sea life on a Hawaiian quilt. Nobody had sea life on a Hawaiian quilt before. And so, he started putting dolphins. And I didn’t realize that until I met another quilter. And then I said, oh, my dad’s John Serrao. And she goes, oh, he’s the sea life designer <laugh>. I was like, okay, I’ve never heard of that before. But that’s, that’s okay. Yeah. He, he took the women’s desires and he says, let’s put it on a quilt. And, and he did it. And he was interested in being able to do that for the women. And so, it was not just a culture of Hawaii, which is in the quilt itself and the echo quilting, but the design started reflecting that specific tradition of that quilter.

JA: Quilts may reflect the ecology and the natural world of Hawai’i, they may tell the story of its creation or they might have a deeply personal meaning:

Cissy: And you have one called Kamekani Kaili aloha, where a woman made a design over the loss of her husband. And it was called The Wind That Took My Loved One From Me. And so you had another quilt called the Kaomi Malie, which means Rub Me Gently, the love between a husband and a wife. And we have one called the Kahili O Enia, where one of the legends talk about how the God Kamapua’a, who basically has a place here on Oahu where they say he exists. But it was not just nature, it was legends, it was desires, it was, you know, stories that touch and that’s what they put into their quilts. That’s why sometimes if we see a design, we don’t like to name it. Because even if it was a carnation design, it could have been made specifically for a loved one or someone. And so, when we see a design, we can say, oh, it looks like a carnation. Oh, it looks like, but sometimes we don’t want to say, because we don’t know what the original intent was of the quilter and the designer. Yeah.

JA: Cissy says that even though Hawaiian quilt design evolves all the time it’s important that the basic principle remains the same

Cissy: The tradition itself is that centre medallion. And then my dad would always say, that centre is your centre, you yourself. And it’s also Hawai’i, because he has always had that belief that Hawai’i was the centre of Mother Earth. Everything started here. And it’s an indigenous tale from all different indigenous cultures. So, you have your medallion at the very centre of the quilt, and they said the echo quilting is the love going out from Hawaii, which is the centre medallion, or from yourself going out to the rest of the world. If you have a border on that quilt or what we call a lei, the love that is going out into that new world and out, it is returned back into the centre. Because when you do a Hawaiian quilt with the medallion at the centre for every quilting line, echo quilting line, you quilt out from the centre, you’re quilting in from the border. So eventually you’re going to have your quilting meeting up together. Yeah. So, every part of the quilt has a significance, it does tell the story of Hawaii, its tradition and its culture, but it also has changed where it’s not just about Hawaii culture. There is a huge significant in the quilt itself, but it tells the story of you, yourself and your family.

JA: All of the quilts that were commissioned by the Pitt Rivers Museum were designed by John Serrao, for Marenka this was an important point of principle.

Marenka: So, all the designs that are in this exhibition were designed by John Serrao specifically. So most of them were created between like this 1970s to 1990s. Although a lot of them also draw on older patterns as well. But the reason that we are very specific about using only John’s patterns is because Hawaiian quilt patterns are not the, they are heirlooms, you know, they’re specific to family, specific to place and you don’t want to kind of use a design that wasn’t meant for kind for commercial reproduction. It might have been for a specific person. They all tell their own stories. And so there have been times in the past when kind of large conglomerates use kind of use patterns without the permission of those families and have run into trouble <laugh>. So, we used ones specifically that we know John created and that were okay to be reproduced within this setting.

JA: Cissy and Rae Serrao gave their permission for these designs to be used and wanted the story of Hawaii to be told properly in these new acquisitions to the Museum. But these quilt designs are imitated and frequently ripped off by commercial companies for profit.

Marenka: Yeah, to me there’s like no excuse for us to kind of fall into that trap of appropriating someone else’s, like family heirloom, their, their intellectual property. That’s what it actually is. And we often don’t like talk about designs, especially indigenous designs as intellectual property. And that is something that a lot of culture groups are fighting for today. But it is, it is something that they’ve created that has been passed on through generations, but has been appropriated many times by many big other big companies and fashion groups that have the money, for example.

JA: But the quilts in the Museum are objects with immense beauty and power, Mana – in the Polynesian languages and as the Commissioner of them, Marenka was required to add something of herself to each one of them.

Marenka: So when I got all these quilts, I had to actually sleep under each one of them. Because that’s kind of the tradition. It’s the idea of, you know, the quilters put a piece of themselves into it. So as the commissioner, I also have to put a bit of myself into it. And if you think of museums, museums are very much like these are accessioned objects. You don’t like handle them without gloves. You don’t sleep under them <laugh>, you know. And so it’s kind of what I call cultural care or cultural conservation. It’s not what we usually think about as a museum conservation. But it is what the quilters ask for. And it’s, so it’s kind of like a kind of a contract between me and them saying that I will care for these. And part of caring for them is me taking a nap under each one. <Laugh>.

Jo: So, excuse me, but where did you take this nap?

Marenka: Oh, I just, you know, did it in my office. <Laugh>, don’t tell anybody I nap in my office, but I often do <laugh>. But yeah, it was just, you know, 20 minutes. I did a one a day, so it was 15 days. <Laugh> of a little bit of foot love. Yeah, so that is, I mean, I, I need to do a lot of things for some of the commissions. So this one’s actually fairly easy ’cause I love napping.

JA: But there is something even more remarkable about these quilts which have come to represent so much about Hawaiian life, and the stories of people who first settled here. Woven fabrics came relatively late to these islands. They were not part of the traditional culture of Hawai’i. Hawaiians originally had a rich but very different material culture – represented perhaps most famously by the intricate and beautiful feather capes or ‘Ahu’ula:

Catherine: Those feather capes were not only made for for male chiefs, but also for warriors. Sometimes it would be worn in war and battles. And those are really symbolic, especially for our chiefs. You needed to have a lot of people go into the forest to, to catch the birds. And then to get the birds off the nest, and then pluck the feathers off of the birds. And that took a lot of time. And imagine they were mostly taking yellow for Hawai’i island. Those were the most rare, the yellow feathers, red feathers, and sometimes black and green feathers. And they were thousands and thousands of yellow feathers, or just bird feathers in general to make one ‘ahu’ula, a feather cape, or a cloak, or a kahili, which are other objects that were waved to symbolize the presence of a chief. So, can, you can imagine the importance of an aula and how much resources it took for the chiefs to get to make that. But also, because birds would fly into the air. They also symbolized the gods that the Hawaiian chiefs descended from and were physical representations of. So we believe especially at that time, that our Ali’i, our chiefs, were physical manifestations of our gods. So when they wore the ‘ahu’ula or the ‘ahu’ula or feather objects were, were waved. It symbolized a chief’s presence as well as it reminded people that they are descendants from the gods.

JA: Catherine ‘Imaikalani Ulep is a historian of Hawaiian material culture. She says that at the other end of the scale, cloth for every day was Kapa cloth or barkcloth made from the bark of the mulberry tree. It was adaptable and easily replaced when it came to the end of its life, but it didn’t last long and it was time consuming to make. Hawai’i is one of the most isolated Island groups in the world but even here woven cloth began to appear in the late 1700s:

Catherine: And that’s a largely when we see a lot of European ships crisscrossing Pacific to access markets in China. And the trade of cloth is one of the, one of the one of the early, early material objects along with other things. They were trading for guns. They were trading for ivory, ammo, ammunitions. There were a lot of other things that were being traded, but cloth was really significant for several reasons. Number one, cloth became almost like currency. And even in America, right? Cloth was currency in early America as well, in the early 1800s. Well, it was the same in Hawai’i. Cloth was currency and was really, really important. In ship logs, we would see the, the sailors taking out a lot of cloth when they would come to Hawai’i. My research shows that sailors were interacting with Native Hawaiian women on a high level. So, we can easily infer that a lot of times they were bartering with these women for cloth as well as, as Native Hawaiians later on went to work on ships as seamen. When the ships log show that when they were discharged, meaning when the Kānaka Maoli men were discharged, they were paid in cloth. When they, the Christian missionaries from came in the 1820s, they were asking for a lot of clothing and cloth from, from Boston. They were writing letters saying, please, please send more cloth, because they would try to pay Native Hawaiians who would work for them in cloth. So, cloth was really, really important in early Hawaiʻi.

JA: On March 30th 1820 the Thaddeus, an American ship carry missionaries from Boston came to Hawai’i to settle. The story goes that the missionaries’ wives brought fabric, thread and needles with them – as well as a lot of assumptions about how Hawaiian women should behave – and they held the first sewing circles in Hawaii – Here’s Cissy Serrao:

Cissy Clip 6 Dress:

So Hawaiian quilting itself was not the first thing they talked about. They talked about how to make clothing, how to dress the women, you know. And so the missionary women, they, you know, they really worked hard with the Hawaiian women in trying to say, okay, cook for the husbands, clean the house, and you know, that’s what they did. Cover yourselves up. Yeah. Cover <laugh>, basically cover yourself up, what can you say? Right. Okay. So what happens is that they did eventually Hawaiian, not Hawaiian quilting, but quilting came into Hawai’i and they started doing more patchwork styles of quilting, taking fabrics from what we understand and sewing it back up together. A lot of the fabric was coming from the East Coast, and the fabric would be scrap fabrics, and some of them would be good fabrics. you know, there’s a saying that say, oh, they cut it up and they sewed it back up together again, that could be true because of the different styles of type of quilting that came in. But it was the tedious idea of having to take fabric and cutting it up, you know, to get that perfect square or that perfect star and sewing it back up. And the Hawaiian women, time is precious. Time has always been precious in Hawaiian culture, you know, because of the way we lived back then. And so, they couldn’t see cutting and then sewing things back up again. So eventually they say about in the 18, you know, maybe forties, fifties, you know, they’re not sure the exact time, but you started seeing quilting with that central design, that Hawaiian motive, that reflected Hawaiian nature. And that’s when they say, oh, look at this type of quilt. And it was cut out only in one piece.

JA: Catherine thinks the story may be one of fabrics and skills arriving gradually.

Catherine: Native Hawaiians had enough food and resources to support themselves. We, the they wanted these items, but we really don’t know if it came from missionary wives or even earlier sailors that were coming prior to the missionaries. Then, again, you know, ships and vessels and seamen, they needed to learn how to sew, these sailors needed to learn how to repair their sails. And also, another big trade item is they were trading for Kapa, right. Kapa bark cloth to repair their sails in Hawai’i. So, if you think of it that way, a sailor could have, you know, brought and showed needle craft skills well before the missionaries

JA: And Catherine has found evidence that a Spaniard called Francisco di Paulo Marin known as Manini who arrived in the Islands in the 1790s and became a confidant of King Kamehameha the First was sewing for the Hawaiian elite.

Catherine: And Manini was a really important counsel for Kamehameha for many, many reasons. Manini spoke multiple languages when you have foreign ships coming from different ports. He could speak Spanish, he could speak English, and he can speak Hawaiian, but Manini could sew as well. And in Manini’s journals, he wrote down, well before missionaries came, that he was sewing shirts for the chiefs. So, we can see even well before, the missionaries arrived, we have Manini who is making clothing for, for the chiefs and maybe even other seamen who knew needle craft could have been doing the same thing. So, we really don’t know where the quilting and needle craft and where native Hawaiians wanted it. But we know they did well before the well before the missionaries arrived

JA: The missionaries’ primary objective was to bring Christianity, but the Hawaiians had other priorities. They were interested in learning to read and write, and as Catherine says the elite – the Ali’i – were just as interested in the textiles and sewing skills the missionaries brought with them too.

Catherine: Because that was very important, right? The Ali’i wanted to make sure the people who they’re allowing to stay are going to make clothing and fabric, or clothing and attire, which is highly, highly desirable. And that’s what the Chiefs want, right? So we know because there’s a lot of scholarship that the chiefs want reading and writing. They want to understand reading and writing, and they want to learn it. But I also argue that they want textiles, clothing, and fabric in my own work. And during the first initial years, I would say maybe the first two to five years, the missionary wives, their, their major task is to gain favour. Well, not only missionary wives, the missionaries in general, their task is to gain favour. We see a lot of the men teaching, reading and writing. The missionary wives, on the other hand, are sewing. They’re doing a lot of sewing, and they write, they’re doing a lot of sewing to gain favour from the Ali’i.

JA: And suddenly in Hawai’i it became fashionable to be dressed in full Victorian clothing, complete with, yes, bonnets.

Catherine: And for me, I’m like, bonnets, why would you: bonnets? But that was a very fashionable Native Hawaiian women wanted bonnets because missionary wives were wearing bonnets. So <laugh>, we have Ka’ahumanu, she is a very, very powerful chief, is from Maui. And she even wanted a bonnet. We have later on, native Hawaiian commoner women who wanted bonnets, so <laugh>, and also there are images as early as 1823 with Keopūolani‘s death. She was a high ranking Ali’i as well. And, and those images from her death in 1823 show women wearing bonnets. And we can assume, especially from that image some of the women were missionary wives, and maybe some of them may have also been Hawaiian women as well. But, you know, even as early as then we see in images, bonnets.

JA: These strange and exotic imports were fashions that came and went in Hawaiian society –. But the quilts have endured because they tell a much deeper truth about Hawai’i and its people: Here’s Cissy

Cissy: They symbolize a very cultural tradition. All our stories, our legends, our nature is in the design. And so, they said, if you want to learn some history of Hawaiians, of history of Hawai’i itself, sometimes you just have to look into the quilts

JA And, it probably wouldn’t please the missionaries to know that the sewing skills they spread amongst the Islands have been used in the quilts to reach back past the import of Christianity to a much older well of understanding.

Cissy: Christianity came in and the Hawaiians had lost all their gods. Their whole culture is based on their religion and their Gods. So, when that was taken away, a lot of their culture of who they are was also taken away. A lot of the quilt designs reflect the old culture of what the Hawaiian people missed in the old Hawai’i versus the Christianity Hawaii that we know today. But like all quilting, it developed, it evolves, and it’s still evolving today.

JA: Thank you to everyone who gave their time and wisdom to contribute to this podcast, particularly those quilt makers from the Poakalani Quilt School in Honolulu, whose creations now light up the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. Do go and see the quilts if you can, and if you can’t with the next Friends of Haptic and Hue we will be giving away several copies of the wonderful book Marenka edited about the quilts, called Mauka to Makai, which has pictures of all the quilts and interviews with the quilters too: to join go to www.hapticandhue.com/join. You can find out more about this episode, and see a full script and pictures at www.hapticandhue.com/listen-series-7 . Haptic & Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and edited and produced by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production generously supported by our listeners, who fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. If you do become a Friend there’s an extra podcast every month – called Travels with Textiles hosted by Bill Taylor and me, where we cover a whole range of different textile stories and news. But until then – its goodbye from me and enjoy whatever you are making.