Episode #58

Jo Andrews

In this month’s episode of Haptic & Hue we hear from a well-known winner of the Great British Sewing Bee who has adopted the wartime system of clothes coupons as a way of limiting her consumption of fabric and clothing.

Eighty years ago, Make Do and Mend became the watch words of the day as people eked out their garments, repairing and re-making them over and over again. But clothes rationing in both countries also changed what people wore and hastened technological revolutions. In Britain many people had access to quality, well styled clothing for the first time and in America with luxury fibres scarce, man-made fibres entered the market much more quickly that they might otherwise have done.

Notes:

Julie Summers is an author and a historian who has specialised in books about the 20th century. Her excellent book Fashion on The Ration can be found in the UK Haptic & Hue Bookshop.

Julie has her website at www.juliesummers.co.uk She is also on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/julie.summers00/

Meghann Mason has her website at https://www.meghannmason.com/ and can be found on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/meghannm_makeupandwigs/?hl=en

Her great paper on the impact of rationing in the US and UK can be found at https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations/1390/

Clare Bradley is on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/clare.bradders/?hl=en where you will find a selection of her 1940s makes.

Julie Summers

British Governemnt Wartime Information About Clothes Rationing – Image Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

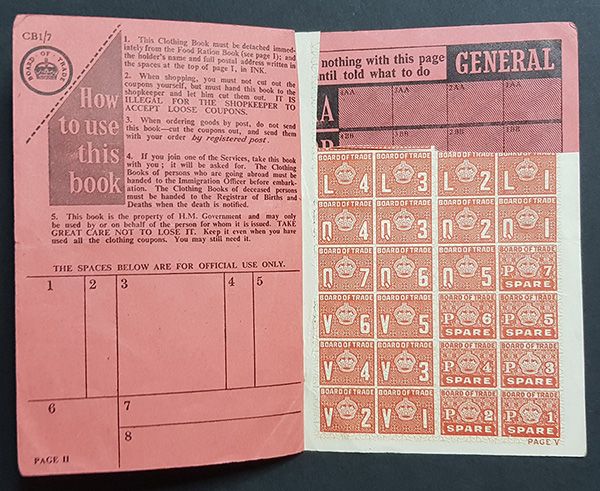

British Clothes Rationing Books with Coupons

The Famous Double Cheese Symbol CC41 – From The Marks and Spencer Archive

British Utility Suit

Close Up of CC41 Buttons on Utility Suit

British Utility Clothing 1943

Hardy Amies, The British Fashion Designer with Models Wearing Utility Dresses He Designed

Meghann Mason

Claire McCardell’s Famous Popover Dress from a 1943 American Catalogue

Claire McCardell’s Popover Dress 1943 Shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York 2021

Clare Bradley Wearing a 1940s Suit She Made

Utility Coat and Suit

Script

Coupons for Clothes: A Wartime Idea Made New?

JA: Welcome to the new episode of Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles – I’m Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver interested in how textiles and fibre change what we know about the human story. This information has been overlooked and often ignored in the formal accounts of our communities. And whatever else is going on in your life, I hope you find the next 40 minutes a calm space in which to hear tales that change the way you think about history, because, it seems to me that being able to understand the past in a better way, helps each one of us find a surer path through the present and the future.

This month’s episode about clothes rationing and the impact it had in Britain and America in World War Two isn’t just an exercise in nostalgia – as enjoyable as that might be. Clothes Rationing has an interesting history in both countries, it permanently changed people’s attitudes to garments and caring for them, but it also brought change and opportunity. More importantly, all these years later, it has some lessons for us all in an age of textile over-abundance. Clare Bradley who was the winner of the popular TV programme, the Great British Sewing Bee in 2020, has re-adopted rationing. She has limited herself to the British wartime standard for the past 8 years.

Clare Bradley: I definitely do it mostly to think about the environmental impact of our clothes, but also the sort of ethical side, thinking about all the fast fashion and the working conditions of people who make cheap clothes and some of the stories and pictures that you see of the conditions that those people work in is really terrible and I don’t want to perpetuate that system. So, I think it’s probably a twofold concern.

JA: There will be more about how Clare manages her modern system of rationing, but the environment and labour conditions were the last things on the British Government’s mind in June 1941.

Julie Summers: What happened was that basically half of all factory production for clothing went over to making uniform for a third of the population. So, the remaining two thirds of the population has only 50% of the factory production that it had pre-war. So, as you can see, that isn’t, isn’t just going to add up. So, the idea of clothes rationing was to reduce the demand for clothes and to ensure that when people bought, they bought thoughtfully.

JA: That’s Julie Summers, her book Fashion on the Ration is an enjoyable account of how rationing worked and the impact it had on people. She says the Government had been thinking ahead about how they were going to provide for all the uniforms they would need.

Julie: And rather brilliantly, the British government bought the entire Australian, New Zealand and South African wool clip in 1939, in the full knowledge that it will be having 15, even possibly 20 million people in the armed services and various other services that require uniforms. So, clothing was very much on the government’s mind from the get-go. And by 1941, several things had happened. One was that a lot of shipping had been lost in the North Atlantic, so there was a real shortage of materials, and there was a real focus on JA: Welcome to the new episode of Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles – I’m Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver interested in how textiles and fibre change what we know about the human story. This information has been overlooked and often ignored in the formal accounts of our communities. And whatever else is going on in your life, I hope you find the next 40 minutes a calm space in which to hear tales that change the way you think about history, because, it seems to me that being able to understand the past in a better way, helps each one of us find a surer path through the present and the future.

This month’s episode about clothes rationing and the impact it had in Britain and America in World War Two isn’t just an exercise in nostalgia – as enjoyable as that might be. Clothes Rationing has an interesting history in both countries, it permanently changed people’s attitudes to garments and caring for them, but it also brought change and opportunity. More importantly, all these years later, it has some lessons for us all in an age of textile over-abundance. Clare Bradley who was the winner of the popular TV programme, the Great British Sewing Bee in 2020, has re-adopted rationing. She has limited herself to the British wartime standard for the past 8 years.

Clare Bradley: I definitely do it mostly to think about the environmental impact of our clothes, but also the sort of ethical side, thinking about all the fast fashion and the working conditions of people who make cheap clothes and some of the stories and pictures that you see of the conditions that those people work in is really terrible and I don’t want to perpetuate that system. So, I think it’s probably a twofold concern.

JA: There will be more about how Clare manages her modern system of rationing, but the environment and labour conditions were the last things on the British Government’s mind in June 1941.

Julie Summers: What happened was that basically half of all factory production for clothing went over to making uniform for a third of the population. So, the remaining two thirds of the population has only 50% of the factory production that it had pre-war. So, as you can see, that isn’t, isn’t just going to add up. So, the idea of clothes rationing was to reduce the demand for clothes and to ensure that when people bought, they bought thoughtfully.

JA: That’s Julie Summers, her book Fashion on the Ration is an enjoyable account of how rationing worked and the impact it had on people. She says the Government had been thinking ahead about how they were going to provide for all the uniforms they would need.

Julie: And rather brilliantly, the British government bought the entire Australian, New Zealand and South African wool clip in 1939, in the full knowledge that it will be having 15, even possibly 20 million people in the armed services and various other services that require uniforms. So, clothing was very much on the government’s mind from the get-go. And by 1941, several things had happened. One was that a lot of shipping had been lost in the North Atlantic, so there was a real shortage of materials, and there was a real focus on concentrating the clothing manufacture towards uniform.

JA: Julie says this wasn’t just about uniform though – it was about all the clothing they needed for the different jobs they were asking women to do as well.

Julie: And if they were going to ask girls, for example, to go and work on the land, or it, it’d be the timber girls, they had to have clothes for them. So it was very much part of government thinking all along. And although Churchill initially was very much against rationing, Oliver Lyttelton, who was the president of the Board of Trade, managed to persuade him on, on the grounds that they simply did not have enough clothing to keep the country clothed if they didn’t start to ration.

JA: So on June 1st 1941 – well over eighteen months after the war had started, the government issued clothing coupons for everyone in the country. People got 66 coupons to last them a year and under the scheme it took 18 of those to be allowed to buy an overcoat, 11 for a woollen dress with sleeves, 8 for a pair of men’s trousers, 4 coupons for a woman’s blouse and 2 for a pair of underpants or briefs.

Julie: And that was calculated based on some research done by a person at the Board of Trade and a woman in the Bank of England. And between them for 10 years, they’d been looking at what the British clothing, average clothing purchase was, and therefore the Board of Trade based the 66 coupons on average spending. So people had very, very few clothes in those days, and Mass Observation did a survey in 1941, just after clothes rationing was introduced, where they established that the average working class woman had one skirt, one dress, one pair of shoes, two blouses. The average working-class man had one suit, one pair of shoes, and a pair of clogs. Now, a middle-class woman might have two skirts, three dresses, a couple of cardigans, and maybe one two-piece suit. So, people had very, very many fewer clothes in their wardrobes than we do today.

JA: Even so rationing was extra labour especially for women who had to manage the coupons for their families, clothes became horribly expensive and it didn’t solve the Government’s problems.

Julie: But of course, what happened was there was a colossal shortage throughout because clothes rationing helped, but it didn’t solve the problem of lack of factory space, which had been basically put over towards uniform production.

JA: So, the Government then introduced austerity design, it told the factories exactly what kind of fabrics they could produce and they seriously limited the sort of designs they could make with them:

Julie: And what that did was to was to gather together the little factories and try to turn them into bigger factories. So, people had to work together. And they also limited the number of runs of material dramatically. So rather than having something like 1,700 different types of cotton, they reduced it to six different types of cotton. So you could do massively long runs, which was far more economical. But the government realized this was going to be very unpopular because it would limit the different fabrics. So, in a really brilliant move the Board of Trade got in contact with Audrey Withers and Harry Yoxall, who were Vogue. And Harry Yoxall was the managing director of Condé Nast publications. And Audrey Withers was Vogue’s editor. And, in consultation with them, they came up with not only the idea of the austerity measures, so limited lengths of skirts, number of buttons and so forth, but also with the idea of getting people like Molyneux and Hartnell and Digby Morton to design the clothes in order to give the women of Britain the confidence that they could dress like the Queen, but on a tiny budget. So, a dress would cost 30 shillings rather than 30 guineas, but would be designed by Norman Hartnell. And it really worked. The press loved it. And, and Vogue loved Austerity Design. They really thought it was a very much better solution to the British clothing problem than just rationing.

JA: And while there were still shortages people loved the simple, unfussy, utility clothes that came complete with the very recognisable double cheese symbol designed by public competition. These garments were well made and smart, and for many they were a huge improvement on what they’d had before the war, when you could get them.

Julie: Oh, I think it was. And, and lots of people who I spoke to were very pleased with their utility clothes and said they were extremely comfortable and they fitted very nicely. But they said they were not always available. This was one of the issues. You know, they’d go into a shop and they’d want a size for sake of argument, size 10 skirt and they just were not available. It was, it was a problem of supply.

JA The Government also had an unbelievable amount of control over how clothes were made:

Julie: It dictated the width of the gusset in women’s knickers, which is just extraordinary. On the other hand, it didn’t ration hats. So, you could buy hats. If you could buy hats, you could wear any hats you liked. So, what they wanted to do is to ensure that the staple was utility and minimal in its need for the amount of material, but they wanted you to have fun as well. So, if you could get a hat, you could stick feathers in it, you could wrap tape around it. They didn’t ration gloves. I mean, gloves were difficult to come by, but, you know, gloves were not rationed. So they were very clever at allowing a little bit of freedom while all the time being certain that the coats, the dresses, the skirts, the blouses and the underwear was all perfectly designed. And the other thing that is a bit heart-breaking, I have to say, is that they only permitted six new designs per year. Which if you look nowadays, if you go into Marks and Spencer, for example, and you look at the range of say, bras, there must be 500 different types of bra you can buy Marks and Spencer, but in Britain, the design for the bra will be set, and that’s what you’d have to buy for that year.

JA: Julie says that initially people panicked about clothes rationing but they settled down:

Julie: Initially I think there was just shock because it was so out of the blue. Unlike food rationing, which had been pre-warned, clothes rationing came out of the blue. Literally, it was announced on the 1st of June. The 2nd of June was a bank holiday. So, the shopkeepers had time to get used to it. And I think a lot of women went into panic because they would have stocked up on, for example, stockings or, or blouses or whatever. So initially there was a sort of panic. And then people began to settle down and think, well actually, you know, my old suits will work and we can make alterations and so forth. But quite quickly, there became a very vigorous black market in clothing coupons. And there are stories, and it doesn’t reflect very well on the upper classes, but there are stories of women buying their maids’ clothing coupons from them. And the government clamped down on this, so you could only use your clothing coupons if they were still in the booklet that they were issued in.

Jo: Which had your name on it.

Julie: Which had your name on it, had your number on it. And it was very strict.

JA: It brought about a different way of thinking about clothes, material and yarn, one that never really left the women who lived through that period. The famous Make Do and Mend booklet was issued in 1943, and as the war went on the number of clothing coupons sank, to just 24 per person for one dreadful 8 month period.

Julie: People made their own clothes, made their children’s clothes, and what Make Do & Mend did, it did two things. Firstly, it gave very sound advice, but secondly, it made it not only possible, but actually fashionable to wear patches. So, you could patch clothes, you could stitch up clothes, you could wear multi-coloured leather shoes because leather was in short supply. S,o people had, you know, three different types of leather shoes. And, and those became fashionable as opposed to looking like a poor disgrace, which is to some extent what, what they really were.

Jo: And so people didn’t mind visible darns and patches. They were seen as a kind of badge of honour.

Julie: They were a badge of honour that was encouraged by the Board of Trade. Lyttelton was quite clear. He said, you know, I don’t want women to go around looking slovenly, but to wear a patch is a sign that they’ve made a sacrifice for a man overseas who’s doing his duty for his country. So, there was an element of that. But there was always this thought that actually they were very proud and they did not want to look scruffy. So, there was a super trend in mending stockings. And there were specialist hosiers who would have little booths in the big clothes shops, and they would specialize in blind darning stockings so women could wear their stockings again and again, even though they had you know, rips in them, because the government forbad the sale of silk stockings in October, 1941 or even earlier, I think December 40. So, you know, those precious, precious stockings were much loved and, and desperately sought after. So, anything you could do to mend stockings to keep them looking as whole as possible people did.

JA: It’s eighty years since the Second World War ended and there are very few people still alive in Britain or America who remember clothes rationing. But my father Michael – now in his late nineties has a vivid recollection of going without a vital piece of clothing:

Michael: My memory was that going back to school in I think it was the Easter term of 1942 must have been without an overcoat. I just took a Macintosh. And I suffered for that. I don’t know why my parents allowed this to happen, because they were very good parents. But I went back without an overcoat. I can’t imagine why not. But I got a terrible chill as a result of what, standing on the touch line, watching first 11 football matches, which was de rigour. You had to do that as mandatory, and you froze, if you hadn’t got an overcoat.

JA: Michael and both his parents spent much of the war in uniforms which were provided, and he says clothes rationing was just one of things you put up with.

Michael: We didn’t bemoan it in any way. And I don’t think it was discussed very much. But then you see on whole, during the War, people didn’t care a lot about what they looked like. They kept clean and tidy. because you jolly well had to, and they tried to keep warm in the winter. But there was no question of being smart. This extraordinary description of smart casual was decades away from then. Nobody had thought of that, I don’t think it it reflected on us much at all. I don’t think we thought about it.

JA: Across the Atlantic, America entered the war in December 1941. They had wisely learnt the need for fabric in wartime from the British, and didn’t wait long to bring in clothes rationing. Silk and rubber had already disappeared from the shops because of problems with supply from Japan and China, but just over a month after Pearl Habour, American manufacturers were being instructed what they could and could not make by the new War Production Board:

Meghann Mason: Stanley Marcus of the Neiman Marcus dynasty, he came in as the head of the Textiles Division of the War Production Board. So, they’re the ones that came up with our limitation orders, which were the L85’s. So, anything that was under a limitation order on the tag, it would have the little L 85 next to it, which meant it had been approved to be sold under the limitations. Because the difference in the United States versus like the UK was that the limitations were not placed on the civilians. They were placed on the manufacturers. That’s the main big, big difference between the two rationing programs, especially with the clothing. So it, it really kind of was very effective because the War Production Board relied heavily on propaganda to sell the idea of patriotism and doing your part to get people to go along with this. And one of the things they could say was, you don’t have to lose your creativity. You can still buy whatever you want. But the things that were given to them to buy were mandated by the government. So, I could go and buy it, but I had to buy whatever was in the store.

JA: That’s Meghann Mason who works as the Hair and Make Up supervisor for Houston Ballet, but is also a World War Two enthusiast and wrote her thesis on the impact of clothes rationing in the UK and US. She says that what Stanley Marcus did was to take the 1941 silhouette for men’s and women’s clothing in America and to freeze it. His aim was that with every year the war went on, 15% less fabric would be used in the production of garments:

Meghann: So, by doing that, that’s when they put in the orders of you can’t have a hood, you can only have one pocket. You can’t have a fake pocket. There’s no more fake pockets. You cannot have any Norfolk jackets, which were really popular because they have like the gathering in the back. So, it has like a little baby peplum in the back, but it’s extra fabric. So they were like, nope. I mean it went down to like sleeve circumferences. They had measurements out for that. The only exceptions were like wedding gowns, maternity clothing, and then any religious garments. That was it. That there were no other exceptions. <Laugh> outside of that.

JA: Manufacturers did not step out of line.

Meghann: And they would have very heavy fines if the manufacturers were found to not be complying with the L85 orders. They were heavy fines. There could be jail time. They were pretty serious about it.

JA: Hollywood was recruited to play its part – or more particularly to dress its part. Gone With The Wind was one of the last big costume movies – released in 1939 – before the wartime era of austerity came in.

Meghann: Oh my gosh. I mean, the costumes are amazing. They’re huge. They’re elaborate and luxurious. So much fabric, so much hooping, you know, it was just all the ribbon <laugh> all the ribbon in the world. And the budgets kind of reflected that. And so when we get into the War, what happened is we have what’s called a back stock, right? So in the costume shops that I work in, that anybody works in, there’s just usually a wall of, of bolts of fabric, just bolts and bolts and bolts of fabric. And that’s because if you have to repair a costume or it’s just the leftovers from what you made, you just have the back stock of inventory. And so, the same was with the, the movie studios. They had a back stock of inventory of clothes that they could repurpose, things they could make. So, if they really did want to use kind of a luxurious fabric, it’s not that they would have to buy it, it’s that they already had it. Sequins weren’t rationed, so they could use sequins and things like that. And then later, you know, sequins were made out of plastic, so that helped a lot. You know, they, that wasn’t rationed at all. So, the studios kind of got around having to deal with the rationing in that way.

JA: But was it right in wartime for Hollywood to use this kind of glamour even if they had the fabric in the back stock? Meghann has uncovered memos going back and forth about the way in which the stars were dressed in that iconic wartime movie, Casablanca, which was released in 1942. Hal Wallis was the film’s producer:

Meghann: And he is talking about the new costume changes that came across his desk for Ingrid Bergman’s evening outfits. And he is not happy about it. He said, I need you to look at them and talk to me. But I’m writing you, because the point is, we should think seriously about whether this girl would ever appear in an evening outfit. After all these two people are trying to escape from the country. The Gestapo is after them. They’re refugees making their way from country to country, and they are not going to Rick’s cafe for social purposes. It seems a little incongruous to me for them to dress up in evening clothes as though she carried a wardrobe with her. I think it would be better for Henry to wear a plain sport outfit or a Palm Beach suit, and if she just wore a plain little street suit, somehow or other, these evening costumes seemed to rub me the wrong way. And I, I was so taken aback by that because it is so true. Like they really were conscious of what the American person were consuming, even though it’s Ingrid Bergman. I mean, she’s so glamorous. And he said, absolutely not. Like we need to have a little bit of a reality check here, they’re not allowed to wear these things right now.

JA: It had a dramatic effect on costs. The costumes for Gone With The Wind cost over $165,000 – Casablanca came in at just $22,000. But Meghann says she doesn’t think cost was the point.

Meghann: It doesn’t seem so, it seems like it’s more for the reality of what’s happening. Looking back at photos, Winston Churchill, he went to go visit heads of state right during this time and he didn’t have suits on. And it’s the same thing. This guy is only in this thing. She’s only in this thing. It’s not appropriate for them to be in these lavish things during this time when they’re running from the Gestapo. She’s not gonna be like, oh, I’m so sorry, we’re going to dinner. Let me put on my beaded gown. Like, she’s probably hot <laugh>, you know, she just wants a cocktail and just to relax for a minute. And when you go back and watch Casablanca, the lines and everything in that film are very simple. Nothing is over complicated and overworked at all.

JA: Rationing changed American women’s experience of fashion and like their British sisters they learnt to make do and mend – lessons that stuck with them all their lives. But this new era also set free American design. Up until then, everyone had looked to France for new fashion trends, but Paris was effectively cut off and that gave American designers a chance to shine and they were a breath of fresh air – one of the best known was Clare McCardell.

Meghann: She really came to the forefront in this time period. And she had already been working in the Thirties and early Forties and was a really big proponent of like American women in sportswear, think Katherine Hepburn, Marlene Dietrich to a certain extent, but wearing the pants and riding the bikes and going to the beach and just a kind of a woman of practicality that was like, we don’t have time to deal with all this. I have kids, and can I have something that’s easy to wash please? that didn’t need to go to the dry cleaner. So, she came out with some really amazing designs during this time. One was called a popover dress, which was really more of like a wrap, but it was very easy, right? It’s very quick. It could be belted. It was a really light-weight material. Of course, it did have to go with the L85 regulations, but the popover dress was originally like a $7 utilitarian dress. And so, then she could put in different colours and things like that and have a lot of fun with it.

JA: And even though Paris re-asserted its dominance after the War with Christian Dior’s New Look, that clean all-American girl trend never quite left us either. The other thing that happened in the US is that the war gave the production of synthetic fibres a huge boost.

Meghann: So wool was out, right? Wool was also one of the first things that was pulled for the military for their uniforms. And so you had to repurpose the wool and things like that. So, one of the things that they had to come up with was a synthetic fibre that could mimic wool. And so, they came up with, you know, the different polyesters. So once this ball got rolling, really in the late 1930s, it has never stopped. And with the accessibility of natural fibres and textiles being taken away, the manmade fibres, I mean, these companies made just hand over fist money with all of these things so the other companies could keep going.

JA: In America, clothes rationing ended as soon as the war did – in 1945, in Britain, which was essentially bankrupt, it dragged on horribly until in 1949 a reluctant government finally rescinded all restrictions. It is hard to believe that this difficult period of our history may have anything to teach us today but Clare Bradley, the winner of the 2020 Great British Sewing Bee, had a moment of insight in August 2017:

Clare: I had a phase when I found a, a shoe brand that I really liked and I bought quite a lot of pairs of shoes from them.

Jo: How many?

Clare: Um five <laugh> in about two months. And, and I still wear some of them now and I’ve had them repaired many times. But I looked at the shoes and I thought, oh, that’s a bit obscene in terms of commodities and stuff. And I wanted to set myself a challenge or give myself a structure of some sort. And I looked around and I came across various schemes that people had used over the years to reduce their own clothing consumption. People have done things like nothing new for a year. One garment in, one garment out. And some of the schemes, particularly nothing new for a year. I thought, well what, what if you get to the end of the year and your, all your clothes have worn out? Are you going to buy a whole new wardrobe? That’s not something you can do every single year. So I wanted to find a scheme that I could repeat if I got on well with it. And being interested in Forties clothing, I was aware of the rationing scheme, so I had a look at it on the internet and I gave it a go. And with a few modifications, I’ve kept it up.

JA: Part of the reason this probably came to mind for Clare is that she has always been known for her love of forties fashion:

Clare: And I think the reason I particularly like and wear more forties styles is I like the balance it gives of you can look stylish, I hope. And they’re also a lot of them very practical. So, for a party dress, I might still wear a fifties big poofy skirt, or a pencil skirt. But those are not practical for riding around town on your bike. Whereas Forties is, you can wear a lovely dress and still cycle into town to go out for a drink in that shape of dress.

Jo: And also presumably it references that kind of wartime thing where trousers came in for women and you can ride your bike wearing a pair of trousers.

Clare: Mm-Hmm <affirmative>. Yes. And I mean the wide leg trousers that I really like, I’ve made three from the same pattern. I do have to tuck them into my socks because they are quite voluminous. But yes, it’s, it’s that balance of realistic workwear, you know, denim was coming in very casual, but you can put those kind of very practical fabrics into your wardrobe and still look feminine. It’s, it’s not my ultimate goal, but a lot of kind of very practical clothes are not very flattering. And so, I like that balance of being able to look a bit girly, but also go out and tromp through the mud in it.

JA: At the beginning of each of her clothes years Clare awards herself 66 coupons.

Clare: When I first started, I really made a game of it. I printed out little coupons, <laugh>, there were pictures if you search on the internet, you can find little pictures of coupons. I printed them out and I cut them off as I went along to really see how my allowance was going down. Now I just keep notes in a little notebook, but as I go along, I will make notes usually just on an app on my phone of things that I might need in the next year.

JA: But when she started not everything went to plan:

Clare: I started in August originally and I found myself using up all my coupons over the winter for heavyweight winter jackets and jumpers and things. And I’d get to about April and not really have much for summer clothes. So last year I shifted my dates and I’m now doing April to April and I’ve now used up all my coupons till April <laugh>. So I’m not sure how well that’s working. But at the start of the year, I have my 66 coupons. I will mentally set aside a small number for things that I definitely need to replace. And as I go through the year, I think of something that I need or I want or a project I need fabric for. And I’ll just consider to myself how many coupons is that going to take? Is that going to leave me short of something else later in the year?

JA: When we spoke Clare still had four months to run on her year and had used up all her coupons – I’m sure it’s a feeling every woman alive in the 1940s would have recognised. But as winner of the Sewing Bee, Clare is obviously a hugely competent seamstress, and she says that making for yourself does help you get more out of rationing:

Clare: It was definitely possible to get more out of your ration by making your own clothes. Part of the coupon cost of the garments takes into account the amount of labour required to make them. So, a very complicated men’s jacket, for example, would be a lot more coupons than a women’s cardigan, for example, because it takes into account not only the cost of the materials, you know, the, the multiple layers of fabric required, but also the hours of labour required to make that garment because labour was also a restricted commodity. So, if you bought the fabric, yes, you could definitely get more out of your coupons. You could eke more clothing out of perhaps a smaller amount of fabric than the commercial patterns were using. You could piece your fabric and there were patterns released that were designed for using very little fabric remaking clothes. So definitely, and obviously then if you bought your own fabric, you could have scraps left over to use for something else later perhaps.

JA: When I met her she was wearing an incredibly stylish pair of beautiful tweed trousers – How many coupons had those cost her?

Clare: The trousers I’m wearing at the moment are a replica of a land girl British pattern. Taken from, there’s someone who’s got a blog on the internet who traced off an original pattern. And these cost zero coupons because I made them out of an old coat.

JA: Clare says her rationing system has changed the way she sees her clothes.

Clare: It’s definitely made me more inventive. And I do look at things in my wardrobe and think how much do I wear that and what could I turn it into? I try not to be too much along the line of remaking something just for the sake of it or just for novelty. And there are definitely booklets from the forties that talk about that, that say, don’t remake this just as a frivolous thing. Remake it if it’s worn out or if you’re genuinely not wearing it, you know, if it’s completely out of style. So, I try not to just do rapid upcycles kind of things, but genuinely transform something into a garment I will wear more frequently.

JA: But she finds it difficult to say if it is just the rationing that has changed her wardrobe.

Clare: I think that’s a little bit tricky to answer because it’s hard to say whether it’s just my style changing as I’ve got older, I don’t care so much what people think about how I look. So, I do dress more eccentrically than I used to five or six years ago. I’ve stopped caring and my colleagues have accepted that. I think the styles are probably perhaps a little bit different. I I’ve always been a relatively plain dresser, so not lots of frills and laces and trims and things. The styles are definitely on the minimalist side, your plain shirts and plain cardigans and things that can be used in different ways or layered, or a top that can be worn with a skirt or with trousers or over something else. So it, it probably does mean that the things in my wardrobe have to serve multiple purposes where maybe they didn’t before.

JA: She doesn’t make everything for herself – she’s a keen hiker and buys all her cold weather and waterproof clothing, but so far, she says system hasn’t let her down – she has found an entry in the old ration books for everything she needs.

Clare: I definitely encourage anybody to give it a go. They could use this scheme. I found it helpful because it’s a preformed scheme. It gives you very clear breakdowns of the coupon cost, but different people have different habits and I would just encourage everybody to find a scheme that works for them, whether that be the one in one out or the nothing new for a year, just try it. And if you’ve been keeping something like that up for a year, you suddenly realize what you can and can’t do without. So it doesn’t have to be this scheme. I’ve just personally found it really helpful.

And if you do want to try this scheme we will be giving away copies of the book Make Do and Mend – Keeping Family and Home Afloat on War Rations, with the next episode of Friends of Haptic & Hue. Thanks to everyone who took part in this podcast. Julie Summers and Meghann Mason for their research and expertise, Clare Bradley for putting it into practice and showing us that the rationing still has something to teach us all, and to my father for searching his long stock of memories.

If you would like to see pictures of ration books and some of the clothes we have talked about then head over to the webpage for this episode at www.hapticandhue.com/tales-of-textiles-series-7. Haptic and Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews. It is edited and produced by Bill Taylor and sound edited by Charles Lomas of Darkroom Productions. Haptic and Hue is an independent podcast free of ads and sponsorship, supported entirely by its listeners, who generously fund us through Buy Me a Coffee or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue.

Friends get access to an extra podcast a month hosted by me and Bill Taylor and in the next episode we will be talking to Mary Ann Williams about the beautiful new book called Textiles of Ireland and to Mary Schoesser about her ambitious new exhibition which celebrates the ancient and deep entanglement between textiles, people and our world. To join Friends go to www.hapticandhue.com/join. But until then its good bye from me and enjoy whatever you are making.