A United Nations of Cloth

The Chatter of Cloth: Episode #19

Karun Thakar believes that every fabric in his collection has a story to tell us about the people who made them and the way they lived their lives, from the luxury of trade fabrics like the Ashburnham Panel to the home stitched art of the Kantha cloth that depicts the sad story of the murder of Elokshi. Karun’s brilliant appreciation of textiles means that he was collecting Kantha cloth, Japanese boro garments, Ottoman and French embroidery, English smocks, Tibetan aprons, Indian Phulkari and more before most of us appreciated them. Now he lends and donates his pieces to museums around the world hoping to deepen the understanding of what they mean and the cultures they belong to. Listen to him talk about why he collects and what he’s trying to achieve in this week’s episode, the United Nations of Cloth.

Runs 36 minutes.

You can find more about Karun Thakar’s collection at http://www.karuncollection.com/

You can also follow him on Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/karuncollection/

Or on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/karuncollection/

The Karun Thakar Fund supporting the study of Asian and African textiles and dress can found at www.vam.ac.uk/research/projects/karun-thakar-fund

Details of the current and upcoming exhibitions that will include parts of Karun’s collection are as follows;

Baghs – Abstract Gardens at the Brunei Gallery, SOAS. On until September 25th

Africa Fashion Exhibition – opening at the V&A in June 2022.

Indian Textiles: 1000 years of Art and Design – opening at The Textile Museum, George Washington University, Jan 2022.

Saima Kaur has written a lovely piece for The Modern Quilt Guild about her connection to phulkari. You can read it here

Books that relate to this episode:

Note: Some of the links will take you to the Haptic and Hue Bookshop at Bookshop.org. If you make a purchase through these links, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a small commission – which goes to support the costs of this podcast. At present Bookshop.org only works for those based in the UK.

African Textiles: The Karun Thakar Collection can be found here

Indian Textiles: 1000 years of Art and Design can be found here

Making Kantha Making Home by Pika Ghosh

Hali Magazine which comes out 4 times a year has lots of well-researched articles about textiles of all kinds. Back issues have a number of articles about Karun Thakar’s collection

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

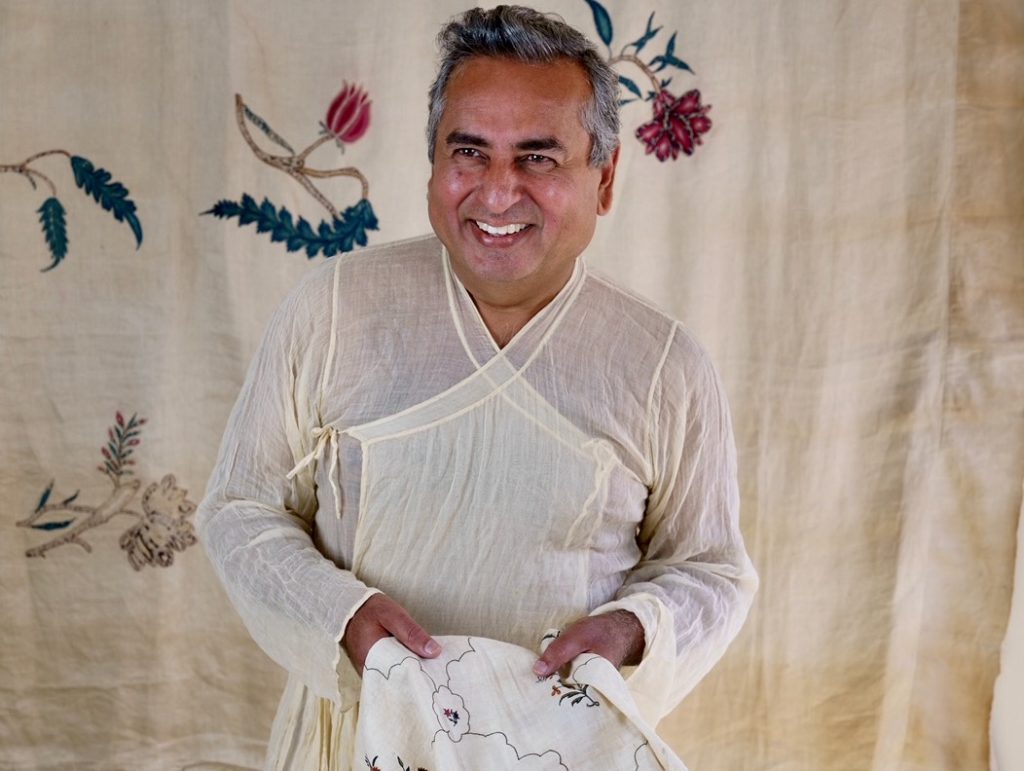

Karun Thakar

Karun Thakar’s Uzbek Suzanis

Karun’s collection of Baghs and Phulkari

The Fragment Karun’s Aunt gave him

Bagh, Karun Thakar Collection

Phulkari, Karun Thakar Collection

Bagh – Karun Thakar Collecton

Bagh Karun Thakar Collection

Phulkari, Karun Thakar Collection

The completed Ashburnham Textile

Detail of Ashburnham Textile

Detail Ashburnham Textile

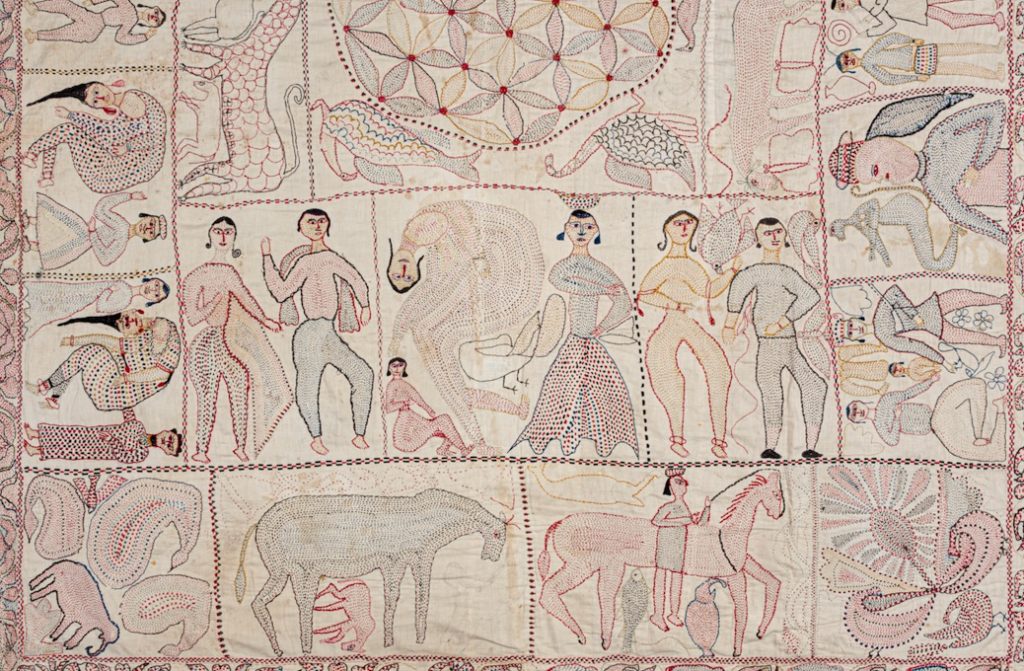

Elokshi Kantha Cloth

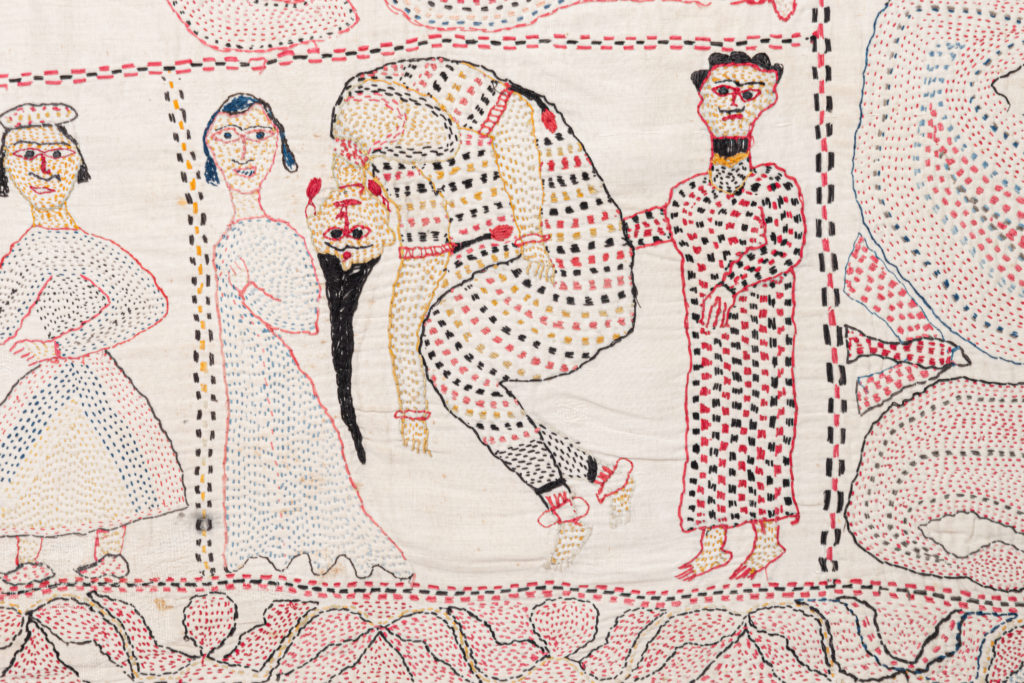

Detail of Elokshi’s Murder

Indigo Dyed Textiles

A United Nations of Cloth

Script

Welcome to the THIRD series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews, a handweaver interested in how all kinds of textiles speak to us and the impact they have on our lives. This series is called The Chatter of Cloth, and each episode begins with a single cloth and then unravels its story.

If you look at a piece of fabric it tells you a great deal about itself. How it feels, what it’s made of, what colour it is, what pattern it has, and you can probably make a guess at what it might be used for. That’s the surface story, and I hope these Tales of Textiles tell that, but they also try to tell another story – the understory. Where does this cloth come from, who made it, or where was this pattern or technique developed and what does it mean to different people around the world, and most of all to the person who owns it or loves it?

The cloth that starts this episode is a fragment, embroidered in red and green silk – one that tells a tale of flight to safety from great danger and is the starting point for an exploration of one of the most beautiful and interesting collections of handmade textiles in the world today. The piece we begin with is called a Bagh – a word that means Orchard in Hindi – it comes from The Punjab, which was split in two in 1947 at the time of the traumatic Partition between India and Pakistan. Hand-stitching Baghs is part of the tradition of Punjabi grandmothers intricately embroidering in silk to cover, completely, a ground cloth. The pieces shimmer and glow with a depth of colour, and they were designed to be passed to their granddaughters to wear on their wedding day.

My aunt gave it to me. It’s a tiny fragment. And within that fragment, there are three fragments each joined. So, I remember, it’s about 35 years ago, she just found out that I was buying Baghs and other textiles, and she’d never mentioned anything like that to me before. So, she produced this piece and started telling me the story of the Partition, which obviously I knew about, and also listening to my mum and so forth how traumatic the whole thing was for the whole family. So while they were leaving, she had to wrap some jewellery. So, she found these three strips of this Bagh that she had, and she wrapped the gold in it and hid them in her purse. And they didn’t bring in any other textiles, basically just travelling with really simple clothes for the fear of being looted, because in 47, The Partition was a huge turmoil for both countries. Millions were displaced, millions were killed. So that tale was very poignant to me. And also the fact that she kept that piece and she hadn’t even told her children about it. They didn’t know about it. My mum didn’t know about it. And when I told them this story, they were not really that interested in it either. So they all talked about the pieces of jewellery which had to be sold how terrible that was because you lose something worth value that they could equate to that. So, it was quite touching that she gave that to me.

That’s Karun Thakar – his story made me wonder: if I faced that dreadful circumstance – the need to leave my home now, taking only what I could carry easily, what textile would I choose and what memories would that cloth hold for me in future?

But this happened to Karun’s family not once, but twice. After Partition his parents left India and settled in Kenya – re-building the family’s fortune with property, and then once again they had to flee in the 1970s when the East African nations expelled their Asian communities. This double experience of loss was traumatic:

Yeah. I mean, if you look around us, what migration does to people, the daily stories we’re reading now, people are arriving with almost nothing with a small bundle of belongings. So you lose a lot. And in particular with the Partition with Pakistan, my parents’ family, mum’s family, they had everything in property. So that’s something you couldn’t lift and move. And then again, moving to the UK, the whole of your childhood you leave behind. For example, I think the first thing I started collecting, which may sound quite odd, is Bollywood film cards. So, I had boxes of those and we had to leave all of those behind, but I left them in the care of a neighbour and a relative. But, unfortunately, they moved and whole things were just dispersed.

This time the family came to Britain, but that was far from easy either:

We came in sort of mid-seventies. it was quite a horrific time for us. Racism was rife. School life was quite terrible for me and my young brother, basically, the only memories you have are how Karun you’re going to survive being abused that day, or running away at the end of school. So if you’re not picked up and beaten then, you know, that’s good. Starting my first job, I was attacked by some skinheads wearing union jack t-shirts and one had a swastika. So those things can have quite horrific memories, but obviously, as I’ve lived here for so long, decades now, and my home is Britain now. So those things evolve, you know, your memories fade and you get support and love and you move away from those and they can become quite positive things.

By calling this ‘positive’ what Karun means is not that the attack was positive – it was brutal and left him significantly injured – but the love and kindness he received in the wake of the attack – which happened just as he had started his first job – has left good memories. And this is something that marks out Karun: he doesn’t ignore hardship but he believes in focusing on the positive. This is important because out of the ashes of his family’s experience of loss, Karun has built up, over many years, an astonishing collection of textiles. He has dedicated his life to this and he has thousands of handmade pieces from Asia, Africa, and Europe.

He lives with his collection in an old 18th-century house in the West Country of England. Opening the door to each room in this home with its bare floorboards is like stepping into a new museum – museums that together form a United Nations of Cloth. Imagine the whispers along the corridors at night, as the Uzbek Suzanis, and the Ottoman Chapans swap stories of hard winters with the overstitched and patched Japanese farmer’s coats, as the hand-dyed and woven Tibetan aprons gossip with the Bengali Kantha cloth, and all the fragments of the Fante people’s glorious Asafo flags chatter to each other about festivals long past.

Their common language speaks of fold and drape, wear and tear, of make do and mend. They form a library of the intelligence of our hands and the determination of human hearts to snatch beauty from hardship, to create meaning from what we have, and most of all to protect, clothe and love our families and communities.

Karun is not a collector because of a great desire to acquire and own – but instead because he is passionate to educate people and to help them understand what textiles mean to us and our societies:

I really don’t want to be sitting in a circle of elderly collectors, mainly white collectors, men talking about how wonderful my eye is, and then folding your objects away and putting it away until you die. And then it comes up for auction. That is not my reason for buying, that is not my reason for dedicating my whole life to these objects. I really want to inspire young people. So when I go to SOAS and I see young people looking around my shows and writing these wonderful comments after the African textiles show, that they didn’t realize there were these amazing abstract pieces being woven in Africa. Because you had the Anni Albers show at Tate Modern, and then people saw the show, African textiles, which were done centuries or decades before that work. And nobody really wanted to cover the Africa show, but that’s just the way a lot of African textiles and arts are covered in the west. So I wanted to inspire that young person to say, I want to study it. I wanted look at that design, or African people who visited that show saying that’s very much part of their history, part of their culture. And they weren’t aware of it. They’d never confronted it. So that is a different form of collecting that I’m trying to promote.

Karun lends and gives, advises and writes, publishes, and photographs day in day out. If you don’t know his name now you will soon. Many of the world’s museums, small and large, are beating a path to his door to ask him to lend his textiles for their shows. And thanks to his work we are starting to see a number of new and different textile exhibitions, ones that are not purely about the lives of elites – like most museum shows – but ones where domestic and handmade cloths made by ordinary working people living tough lives are given their proper place as a critical part of human endeavour.

There is the free exhibition of Indian Baghs and Phulkaris at the Brunei Galley just off Russell Sq in London, the Washington’s Textile Museum’s show on Indian textiles opening in a few months, the V&A’s much-anticipated show on African Fashion next year, or the planned exhibitions on Japanese textile recycling, all these have different parts of Karun’s collection at their heart. There is also the new Karun Thakar Fund at the V&A in London which gives grants and scholarships to study Asian and African textiles and dress.

I wanted to know how Karun started to make this extraordinary library of touch and colour one that has the capacity to change the way in which textiles are seen and assessed by us all.

Everyone has a different answer when you ask a collector, but I agree with what my late friend, Alistair McAlpine used to say: most children collect at an early age. Well, they used to collect. Now they have far more exciting things, like a tablet in front of them, you know who wants to collect little pebbles when you’ve got the whole world on your lap? But people used to collect, especially children. But most grow out of it, you know, they collected cards, or as I said, pebbles, marbles, anything: small dolls, Teddy bears, but people grow out it and it’s something I didn’t grow out of. I remember in Delhi saving my pocket money when I was nine or ten going to the markets to buy little bronzes. And I mean, I bought some Ganeshs, they were only like few pounds and some of the dealers were very kind. They would laugh at me. “That child wants to buy these old bronzes”. I still have some of the bronzes in the cabinet behind here. So, I just felt the need to buy stuff. And it has never left me.

It took a little longer for him to discover that textiles were the things he really loved:

I finished university in the early eighties and I met my partner and Roy was collecting some Oriental rugs at the time. And also he had a couple of abstract EWE textiles. I was fascinated by them and he was a pure mathematician, and he was really into music. So he was really into abstract design. And so that was my first introduction to seeing textiles, which I thought were wonderful. And at the same time, I started to earn, and so I was traveling to Delhi to see my sister who still lives there. And I started looking for embroideries. And in those days around Imperial Hotel, there used to be all these women sitting in rows, selling embroideries. And I had very little budget and I used to see dozens of Banjara embroideries that I was really attracted to, basically, because it was just, I thought abstract masterpieces in small sizes, beautifully embroidered. So I set myself a target of a few each trip, but I only had a maximum budget of five pounds a piece. So I had to limit myself to what I could buy. And also it meant I had to be really selective in looking at things and seeing what I wanted to focus on. So I think that started to train my eye in a way. And then I also felt it wasn’t just enough just to see what was on the market, and living in London I had the Victoria and Albert museum not far away. So, it was very important for me to visit those institutes and see what was being held there, what the aesthetics were of objects, earlier objects, which didn’t actually relate to my Banjara. I was looking at all sorts of European sculpture, medieval art. But to me that was training my eye, I have a similar language, which I was able to transfer to textiles. And then I started to travel to Pakistan, North West, Afghanistan, to quite remote areas. And I really got into costumes. So, I made a huge collection of costumes from those regions. Fortunately, a lot of those areas we can’t travel to and all the material has dispersed which is really tragic because we’re not really able to pinpoint some of the costumes to the exact region they came from.

But Karun did manage to rescue many textiles from this deeply troubled area which will be closed to us now for some time, and that is one of his hallmarks. Karun understood, long before others stumbled on the truth that textiles tell an important part of the human story, rather than just being beautiful things to display.

If I collect and I have to love the things I collect, that has to be the primary goal. I can’t buy things I don’t like. And once I start looking into an area it’s very important, important to me to do proper research in the field. And now I may even consult curators in various museums about those things. So that it is crucial that I have to really think, I have to think about, do I want to live with those things because it is almost impossible to manage this sort of collection. I have very few at little help. So my life is basically looking after objects. It’s a constant, it just doesn’t stop. So people looking from outside say, oh, wonderful, look at your lifestyle, look at the things you have, which I am very lucky to have those things, but my daily life is spending 12 to 14 hours or 18 hours a day looking at things, sorting them out, selecting them for exhibitions. For example, this show, which is opening in January in the Washington Textile Museum, that has been a huge amount of work for the last three years in separate trips to Washington. And in the end, this show, about 80% of pieces which are going to be exhibited, are from my collection. So it’s a huge show for me. So it’s very important for me to stay on top of what I’m buying.

Part of what is important and unusual about Karun’s textiles is that they tell a different story from the pieces in most museums. His pieces are not pristine, they tell tales of human wear and tear, of meaning and belief, of extracting beauty from poverty. He says that museums have huge gaps in their textile collections and that’s because of the people who set up the collections as the 18th and 19th-century museums were established:

So they were mainly made by men, who went out in the 19th century to buy things and they bought what was available, so you don’t have much domestic embroidery. So we’re talking about the lives of women which are invisible in these museums. So we’re talking about in the 18th to 19th century, of the daily lives of women. And to me, those objects are so important. Not only are there visibilizing women, they’re also telling their tales. For example, one kantha I selected recently has embroidery on it with women who look like they are acrobats. But in reality, it was a very tragic case in 1873 of a young girl. Elokshi, who was 16 years old, who was decapitated by her husband because there was a rumour that she was having an affair with the priest and she was 16 years old. So the Kantha actually depicts that murder. So you’ve got the husband holding the dagger. But if you look at this Kantha, a woman who’s decided in the 19th century to make embroidery of it, each stitch around the throat that she’s made in red thread showing the blood gushing out. It’s, it’s almost painful to look at that piece, but she wanted to record it in her way. So it’s, it’s not like we looked at the print or we looked at the news story on it. She spent months embroidering it. And then she also put some dancing figures around it. So, so many things were considered while embroidering that tragic tale of Elokshi. And obviously, the husband just got three years in prison and the priest was released because under British rule that happened. So it’s very important to see what the gaps are in the museum and most museums still have those gaps. You look at Boro textiles, which are very much in vogue, but for the wrong reasons. Because you know, Boro textiles are about the daily hardship of people suffering in north Japan, and whatever people like to say, it wasn’t about aesthetics. They didn’t sit there saying, oh, that blue looks nice I will patch it there. It was what was available they had hemp in it, and whatever they could get, because you imagine the bitterly cold weather in the region. They just layered it. And some of the pieces had backings which had been taken off. So the pieces which I really loved with lots of patches, people wouldn’t even have seen those when they were using it. So that’s another area where there are huge gaps in museums that they don’t have any material of ordinary working-class, poor people. So it’s really important to me to highlight that to show again what it was like for people who didn’t have money, who don’t write history, to make the needlework. So that’s the record they’ve left because they haven’t had the power to write the history for us, but they did have the power to make those clothes.

Karun’s work. is driving a re-assessment of the cultural value and place of textiles overall. But he doesn’t think that they will ever be seen in the same way as painting.

I think it’s interesting because in terms of textiles, you look at contemporary artists, and then you look at the wonderful work of Tracy Emin, Louis Bourgeois. So you have got some women in the western sphere whose work is regarded as important, but you also have the majority of women who are not in the Western world, their work, I don’t think it ever will be, or will have the same power. It used to be the case any time somebody looked at textiles, the first question, and I think there’s been some research, first question people ask, oh, how long did it take? And that is a question, with textiles which is odd: they don’t confront a painting and say, how long did it take or placing themselves in installation and seeing how long did that take? So somehow people equate the length of time it takes to do something in textiles to how good it is. And part of it is, I mean, I understand it is a sort of nervousness of the viewer because if I equate that with the people who are unsure walking into shows, museums, the first thing that hit is the caption. I mean, I’m really anti captions. I would get rid of all the captions. Because I want people to confront the piece and see what it does to them rather than read about it. Because nowadays it’s very easy to get that information digitally, although it never used to be. So, so I think it’s really important that we present those pieces partly as art as well, because some people question that.

Karun stitches, crochets and knits and he knows very well the desire of the maker to understand not just what they are seeing – but also to confront how things are made and what they mean.

I want to see the unfinished pieces. I want to see the drawing, if they’re presented in not just the best in cost context, but in context as an object of beauty, then we’ll appreciate that. Okay. It may not have that use anymore, but it’s still part of that culture, and that culture’s history. Cultures evolve, which is a good thing otherwise where would we be in terms of women’s rights and LGBTQ rights? So cultures evolve and we have to preserve those things. So, we are showing it in a different context, but it is part of your history and part of global dialogue, that informs where people are coming from, what sort of arts they lived with and, you know, I feel so passionately about that.

He also understands that the making and embellishing of textiles have been a creative refuge and means of expression for many women who have led shuttered and constrained lives.

A lot of women talk about the sort of escapist, meditative qualities of a needle in a cloth, making that stitch and I mean as I grew up stitching and crocheting and knitting, from the age of 10 my mum taught me all those things. I still do a lot of stitching, it’s sort of quite grounding to me and you’re really focusing on that small area of stitching. It is very meditative, but I think we have to be careful when we say those things because a lot of 19th-century writing and early writing talk about these happy natives who are singing, dancing, and then, you know, in their spare time they’re doing this wonderful embroidery. You know, you have to look at where women were in the 19th century, especially in rural settings in Africa and Asia. So they had very little time to embroider and also the light factor, but they were still able to do that work.

Karun maintains and houses his entire collection himself, he doesn’t have reams of curators and regiments of restorers, this is just Karun, working largely on his own. He has just spent three years of his life fitting together an extraordinary textile jigsaw puzzle, day in day out sorting small pieces of the Ashburnham Textile.

This is a glorious embroidered piece, produced with a straight needle at the height of the early trade in textiles from the Indian province of Gujarat. It was made in the late 1600s and shows European, Chinese, and European influences. It was installed in Ashburnham House in Southern England as wall hangings, curtains, and chair coverings. In 1953 everything was sold at auction. The Victoria and Albert Museum got a large chunk of this miraculous fabric, another piece went to the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the rest was a ragbag of fragments. A few years ago, Karun managed to buy these pieces, he was determined to re-assemble them so that he could create an entire pattern repeat:

So I spent well over three years working on fragments. Some of them were just bags of embroideries that they’d cut out all the surrounding fabric. I think that was done in the 19th century because whoever had those, they would have taken the embroidery and put them on dresses or bonnets. So it was dozens of pieces, which each one had to be catalogued and photographed, and then HALI magazine, very kindly printed every piece out for me. So we made a jigsaw out of them. So I had to spend months going through the jigsaws because obviously there’s a repeat pattern in it. And my aim was to try to come up with the original yardage of the fabric as it would have been made, to get one repeat. So I was quite lucky that one piece, which is about 2.6 metres long now, shows the exact repeat as the panel would have been done. ‘Cause I looked at the fragments and pieces at Victoria and Albert Museum and the other one at the Metropolitan Museum because there were some gaps. So I was able to fill those. So it as near as complete yardage. And then I’ve also got about at least another 10 pieces. One is another two-metre panel and the others are smaller pieces. So the large repeat panel is going to be exhibited at the Washington Textile Museum. So after sorting it out, there was obviously the really long process of stitching it onto a new fabric. So that took forever with the very skilled conservation people.

This wasn’t easy to do and a tremendous headache both metaphorically and literally but Karun is clear – it HAD to be done:

Oh, because it was dying out to be put together, I just had to do it. I mean, when you confront that embroidery, people absolutely fall in love with it, it’s the most beautiful embroidery to look at and behold, it was a joy to work on. I mean, although it didn’t feel like that some nights when at two o’clock you’re struggling with it.

Karun also has some sound advice for anyone who is thinking of collecting textiles themselves and it doesn’t have anything to do with the size of your bank balance. Rich or poor you too can collect textiles if that is what moves you.

First thing would be, you have to train your eye and see what you like. So don’t just go to one or two dealers and say, yes, I’m going to buy that because it’s written the term rare in front of something. So you have to do your research. It has to be something you really want to live with. If you think you’re going to collect textiles, because they might go up a lot, then I suggest you don’t buy them. Because when I started people used to laugh that I’m buying all these dresses and textiles because no one was seriously buying them in the quantity that I was buying them in the Eighties. And I was buying them because I loved them. I didn’t think they would go up, or that Museums would buy them or there would be shows of them. So you have to be really careful that you want to buy them because you love them. And the second thing is that you, I mean, I keep saying and going back to that about training your eyes, that is so crucial because even working with a lot of curators that I come in contact with daily, for example, let’s say EWE weaving, which is the most beautiful weaving from Ghana. Most of them would have only seen two or three pieces. And then I don’t think they can make informed decisions when they’re exhibiting one in a show. I mean, I travel and I go to see, I’ve seen tens of thousands of them. So, you really need to see a lot of pieces to see what is it that you love about that textile, then focus on those. And the other thing is, as we know, a lot of early textiles are, because a lot may be in vogue or going in and out of fashion. So the prices go up and down, but they tend to be quite expensive early textiles. But I don’t think there’s ever a time when you can’t find something new to collect, particularly with textiles. So a number of years ago, I started buying English smocks, working men’s clothes. ‘Cause they were not very expensive at all. And I have a good collection that will go to a museum, but I mean, they have become quite expensive recently. But somebody pointed something out to me on eBay recently, they were like samplers, pockets and little dresses, buttonhole sleeves done by young women in Victorian times. So they are early pieces because then 60% of the time young girls spent doing needlework in schools. So there’s a lot of that material and for 20 pounds people can buy this beautiful part of history, and they’re so wonderfully done and the whole story of young girls learning to sew in schools is there. So there is always something to buy as far as I’m concerned. The other thing which I think you should think about is dates, you shouldn’t focus on dates. There is a recent international show and a very prominent international dealer dated something as 1700. And I knew, and some of my curator friends knew, it was dated from 1890s. So just by giving a wrong date to something, an early date to something, doesn’t make it good. So I would focus on those things.

Karun passionately believes in trying to attach the right information to the right textiles and he has a healthy disregard for some of the so-called fact attached to some items.

So there is a lot of misinformation about textiles, and I think people feel just because you repeat it, doesn’t make it fact. So, you’ve got a number of shows happening even in the Museums. So you’ve got people with this agenda, particularly some dealers who are selling material to a museum, they’re selling a story which is made up, they’re giving dates which are made up. And then these museums are putting on shows because somebody donated these things to them. Or you’ve got some makers as well who have their own agenda because they want to sell their work. So they’re making up history, making up stories. So it’s really important for me that we challenge that. So we don’t just replace one set of misinformation with another set. So if we are decolonizing information, really inspecting things, we also need to have a critical eye about what we are saying, where the information is coming from. So we should be able to challenge makers and dealers.

Karun knows that his stewardship of these pieces will come to an end when he has run his life’s course. His aim is to give them all away, and is this his generosity is matched only by the immense sense of responsibility he feels for his collections:

Yes, I do. Totally. I feel totally responsible for them because you know, some of the pieces I’ve got, they were made in the sixth and eighth century, some Indian textiles exported to Indonesia in the 13 hundreds, you know, you’ve got eight metre yardage of a textile, which was made in the 13 hundreds, and none of them survive in India. So, you are getting it from Indonesia, it’s arrived in London, I have bought it. So my lifespan is a very tiny blip in the history of those, it comes and goes. But what I want to leave is – I don’t like the term legacies – but I want people to see that I looked after them and not only just looked after them because there are a lot of very wealthy people who can buy priceless things, you know, they can afford anything. I can’t. What I want to do. That’s why I spend all my time researching, publishing, doing books, writing essays, doing exhibitions, spending hours, you know, in between getting migraines, which are constant so that people know about and learn about it. That’s what I want to ensure. Not that I collected it.

Thanks to Karun Thakar for being so generous with his time, and for his passion for textiles – it is something we will all benefit from. Thanks too to Bill Taylor of The Lark Rise Partnership who edited and produced this episode, and to all those listeners who helped to make this third series possible by supporting it via the buy me a coffee button on our website.

You can find pictures of some of the textiles we have been talking about in this episode at www.hapticandhue.com/listen, where you will also find a full script, and details of some of the exhibitions that Karun is contributing to.

Next time we will be looking at a pattern that has become truly global – one that unites east and west. It has a history that tracks back several hundred years, find out more next time, meanwhile, thank you for your company, and thanks for listening.