Strong Community Threads: The Folly Cover Designers

Episode #33

The Folly Cove Designers were an extraordinary group of people who created beautiful and inspirational textile designs in a small community in Massachusetts. They had no professional qualifications and they were taught around a kitchen table by one woman. For nearly thirty years they formed a close creative and supportive network making work of the highest quality. Even today, over half a century later the story of the Folly Cove Designers has a lot to tell us about how excellence happens and why communities matter.

The people you hear in this episode are:

Susanna Natti, the daughter of Lee Kingman Natti, who was one of the Folly Cove Designers.

Martha Oaks, Chief Curator of the Cape Ann Museum, which houses a wonderful collection of the Folly Cove designs and histories of the designers.

Oliver Barker, Director of the Cape Ann Museum.

Barbara Hoffman Souza, Kindergarten Teacher and Folly Cove Designer.

Trenton Carls, Head Librarian & Archivist at the Cape Ann Museum.

You can find the Cape Ann Museum online at https://capeannmuseum.org/ and on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/capeannmuseum/ From Saturday, October 8th they have a new exhibition opening about the Folly Cove designers at the Museum called: Designed and Hand Blocked by the Folly Cove Designers, drawing from its own collection and other lenders and exploring the group’s place in the Arts and Craft movement in America. You can find out more here. I enjoyed visiting this museum, it’s a great example of a small museum that has a lot to say and a great deal in it that is interesting – it’s also clearly well grounded in its own community. I’d be delighted if this was my local museum – no such luck I fear!

If you can’t get there, and most of us won’t be able to, many of the Folly Cove designs are also online in the Museum’s database and can be explored here.

There is also a new book coming out next month called Mid-Century Women Printmakers Virginia Lee Burton Demetrios and The Folly Cove Designers. It has been written by Elena Sarni and can be pre-ordered in both the Haptic & Hue US bookshop and the UK bookshop. Ordering from these bookshops supports the podcast in a small way at no extra cost to you.

You can follow Haptic & Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic & Hue name.

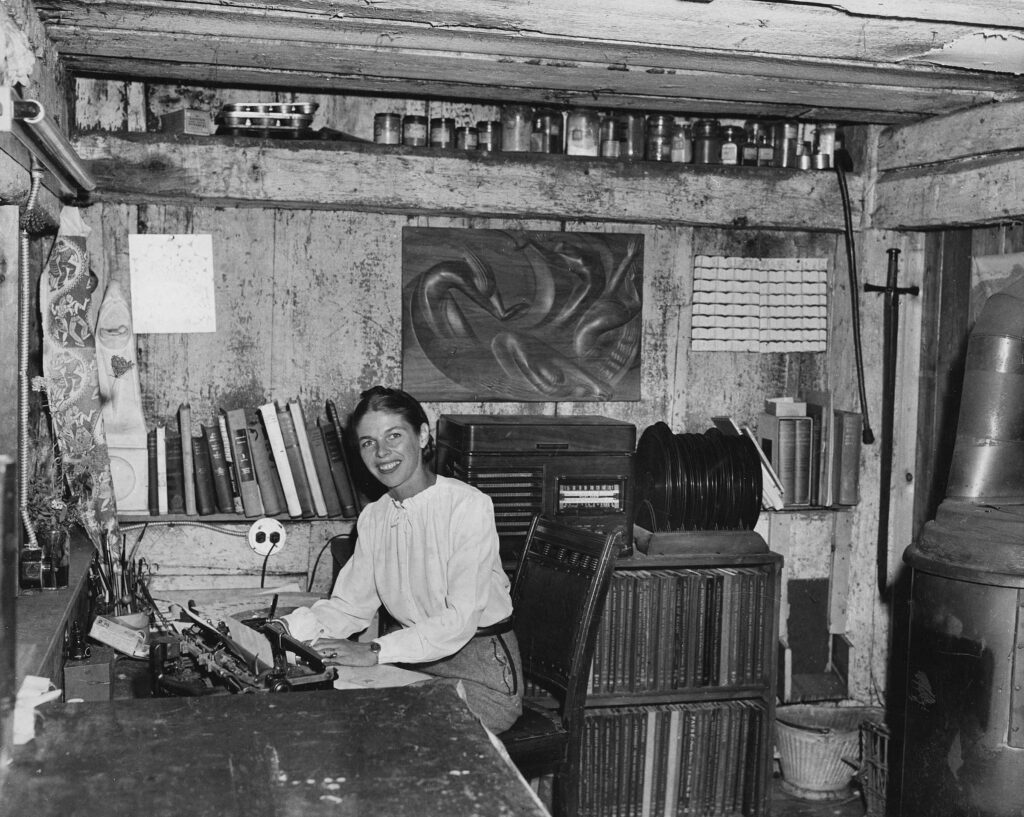

Virginia Lee Demetrios, 1948. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives

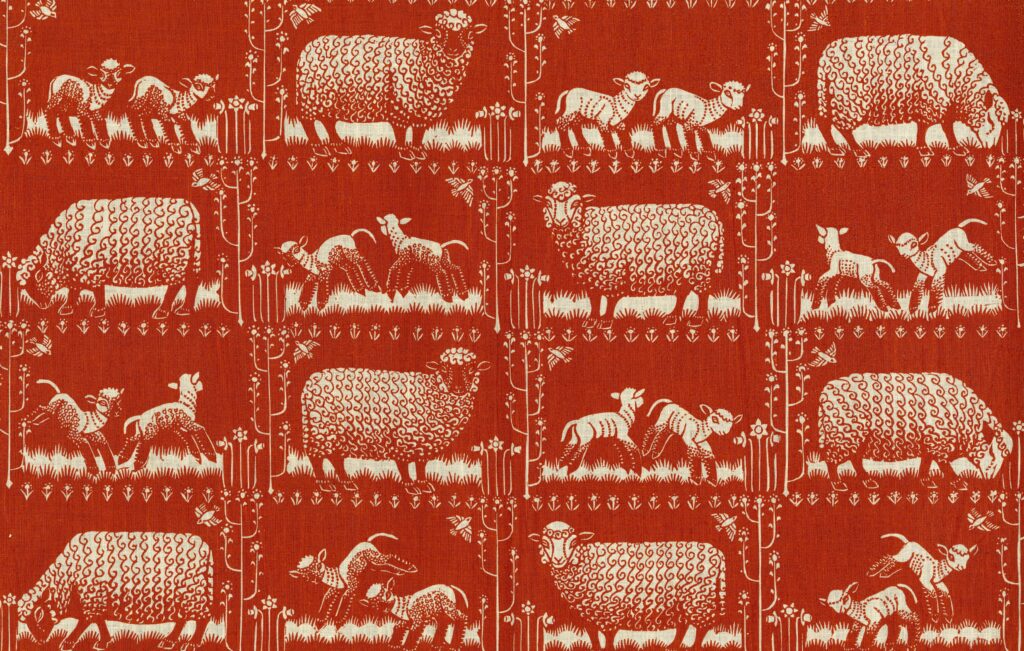

Spring Lambs II – 1951 Virginia Lee Demetrios. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

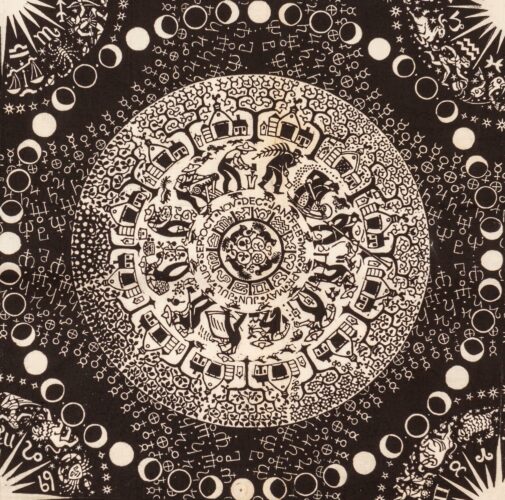

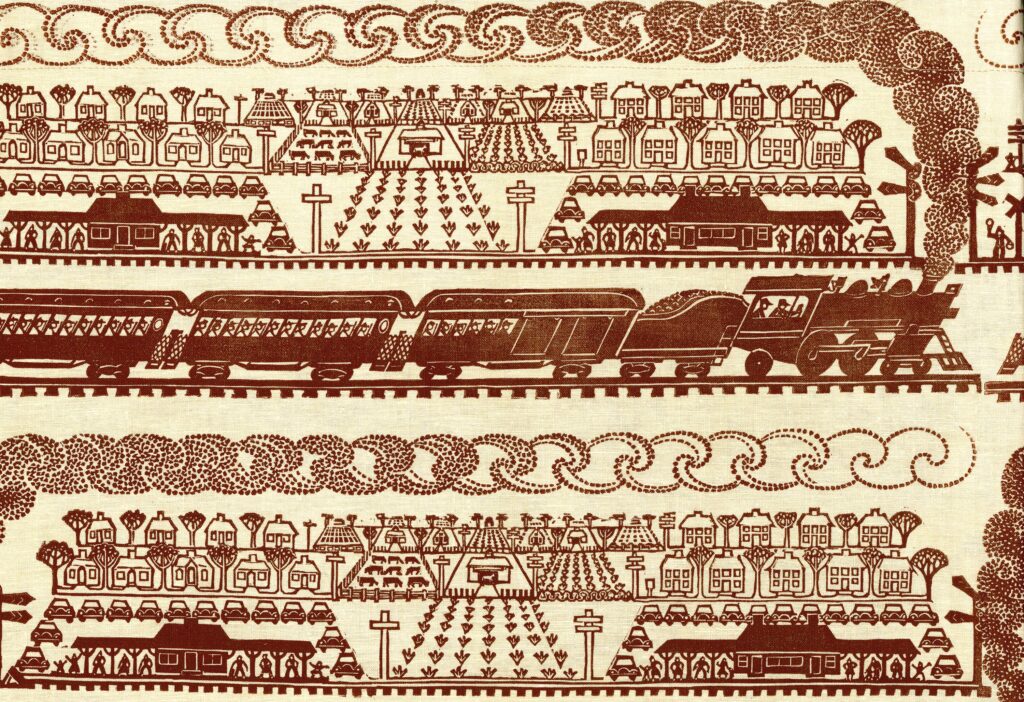

Farmer’s Almanac – 1954 Virginia Lee Demetrios. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

Susanna Natti

Lee Kingman Natti. Courtesy of Susanna Natti

Susanna, aged five, in one of her mother’s prints called Ring Around A Rosy. Picture courtesy of Susanna Natti.

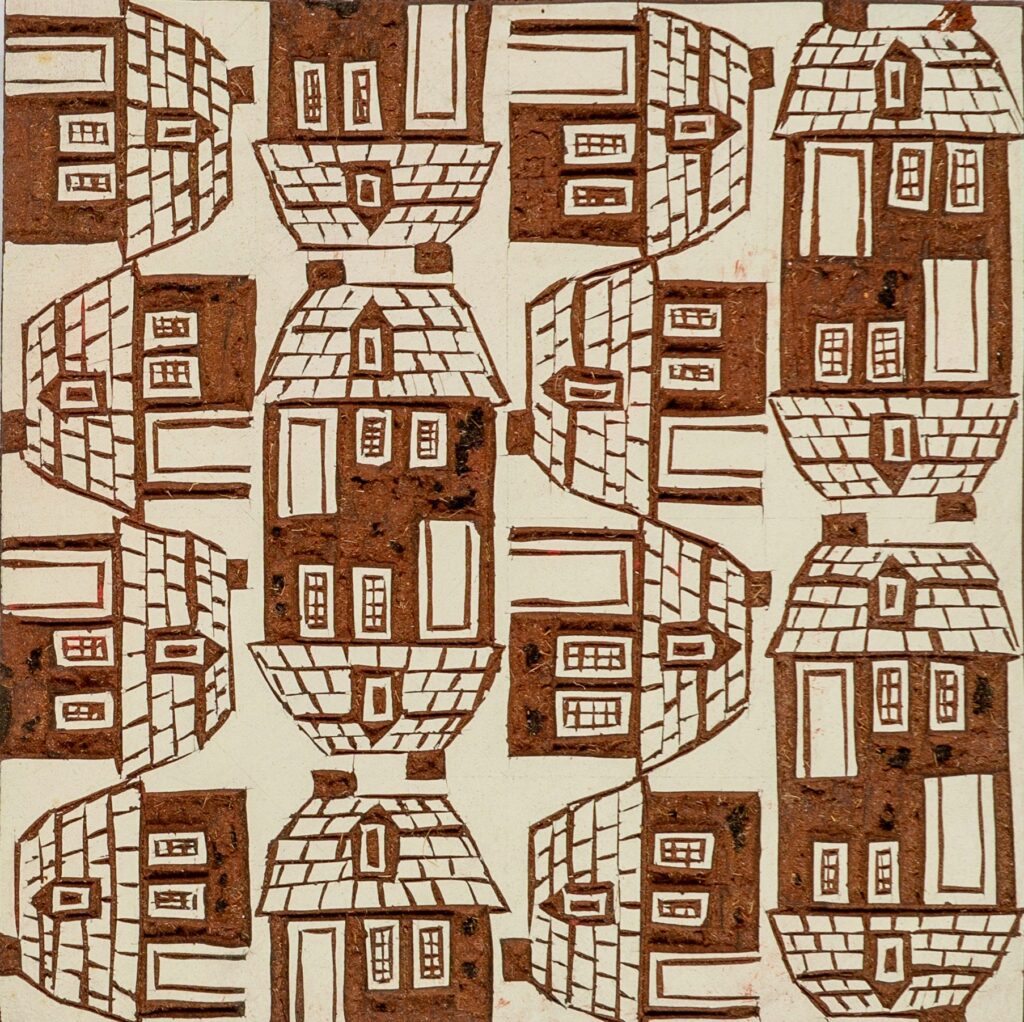

Homework for ‘Story and a Half House’ – Peggy Norton 1958. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

Commuting – Virginia Lee Demetrios. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

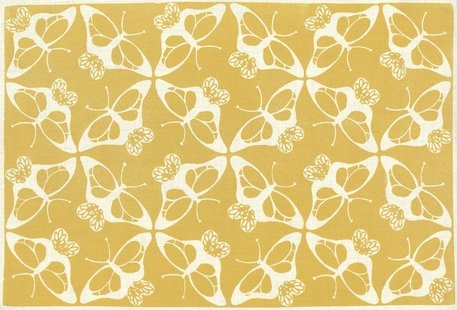

Butterflies, Elizabeth Iarrobino. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

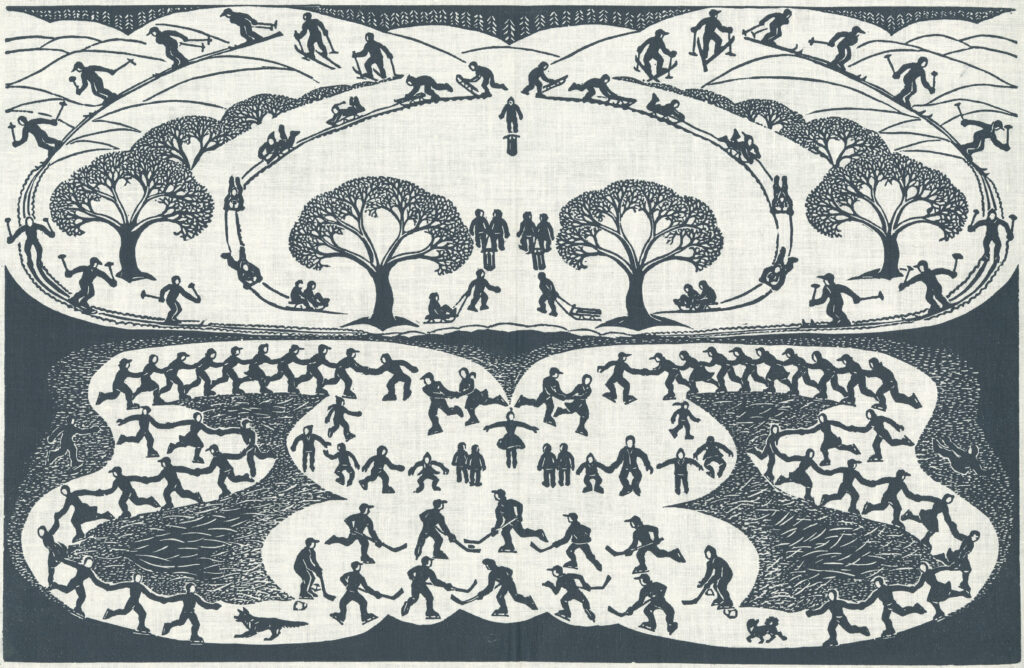

Winter Sports, 1958 Eino Natti. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

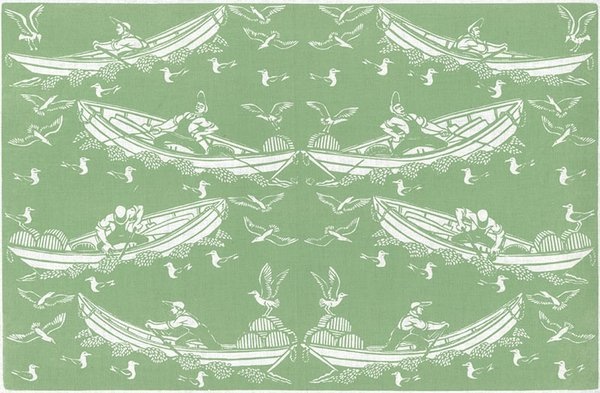

Yo Heave Ho – 1955 Eino Natti. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

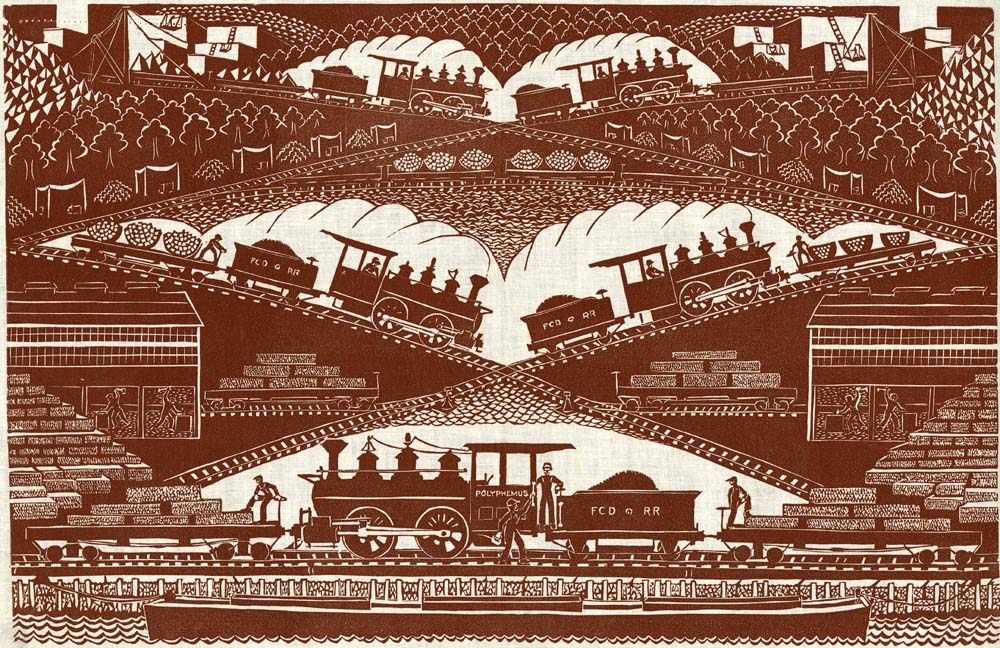

Polyphemus – 1950 Eino Natti. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

Members of the Folly Cove Designers Reviewing Designs Virginia Lee Demetrios third from left. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

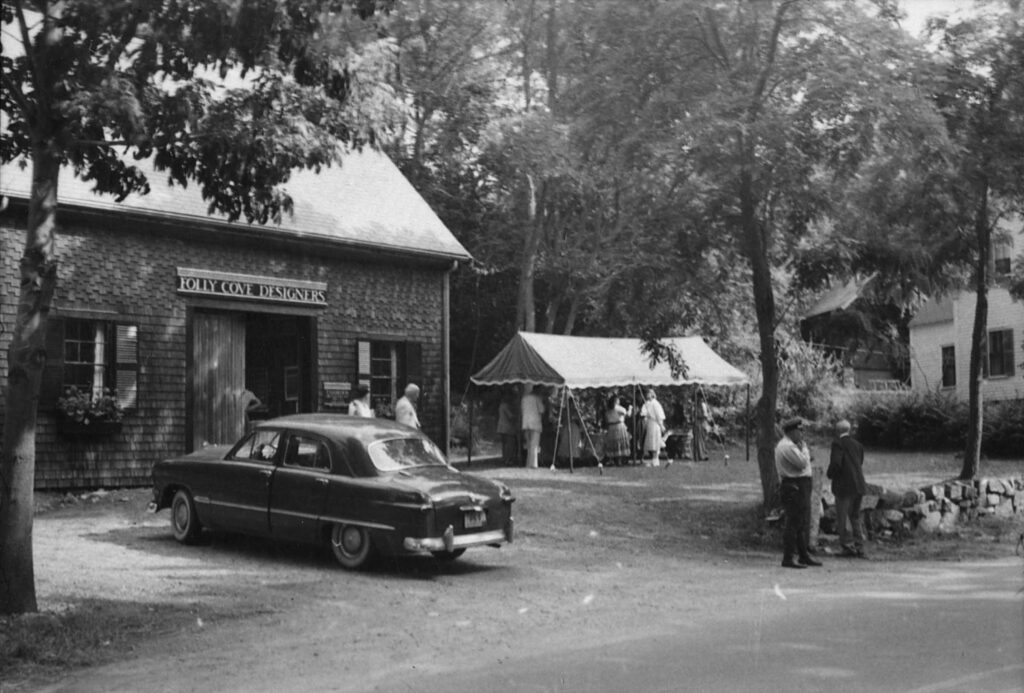

Folly Cove Designers Barn, 1951. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

Reviewing Designs, Folly Cove Designers – 1945. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

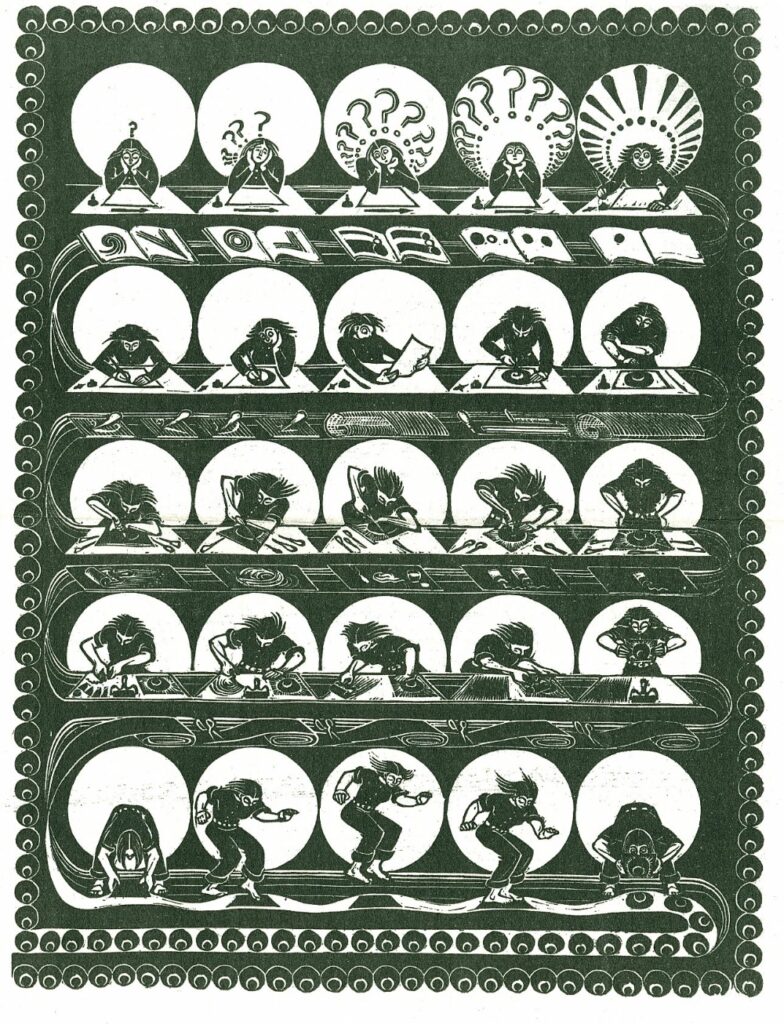

Diploma designed by Virginia Lee Demetrios for Folly Cove Designers. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

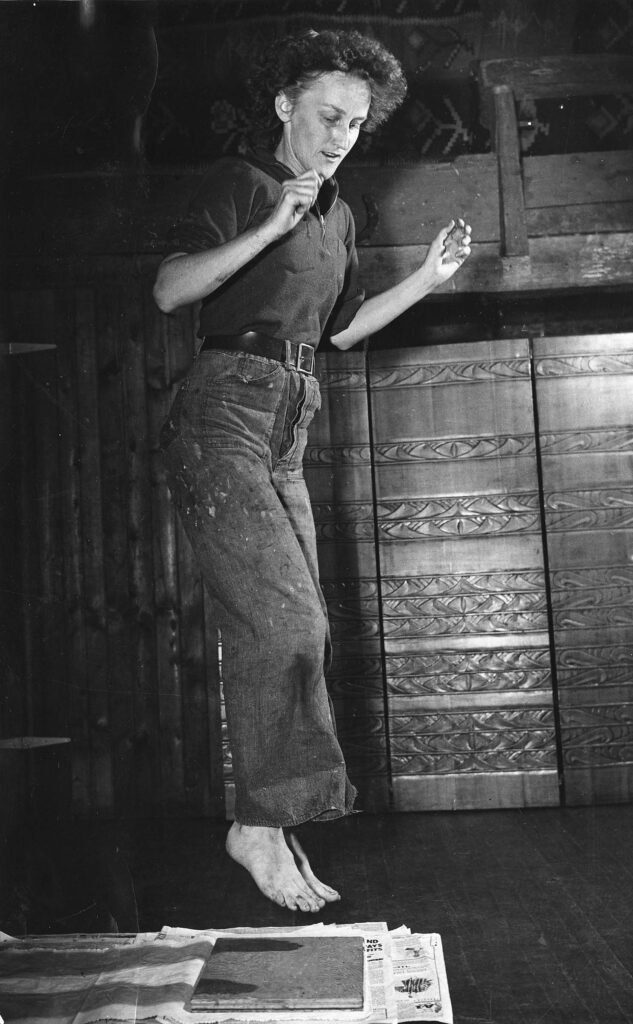

How to Print Without A Press. Aino Clarke jumps on her blocks – 1948. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

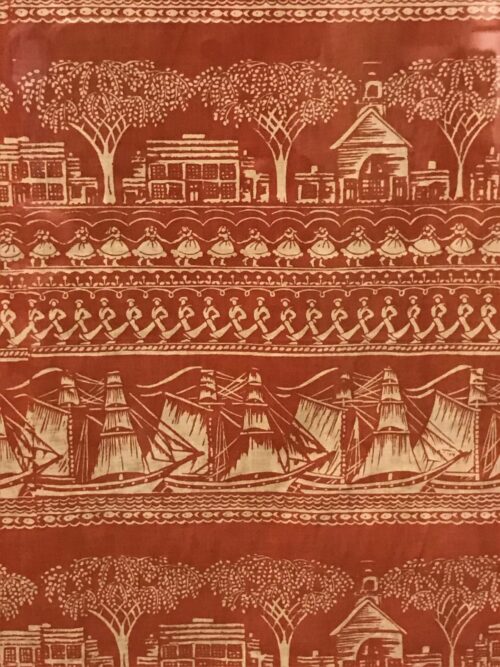

Home Port – 1949 – Louise Kenyon. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

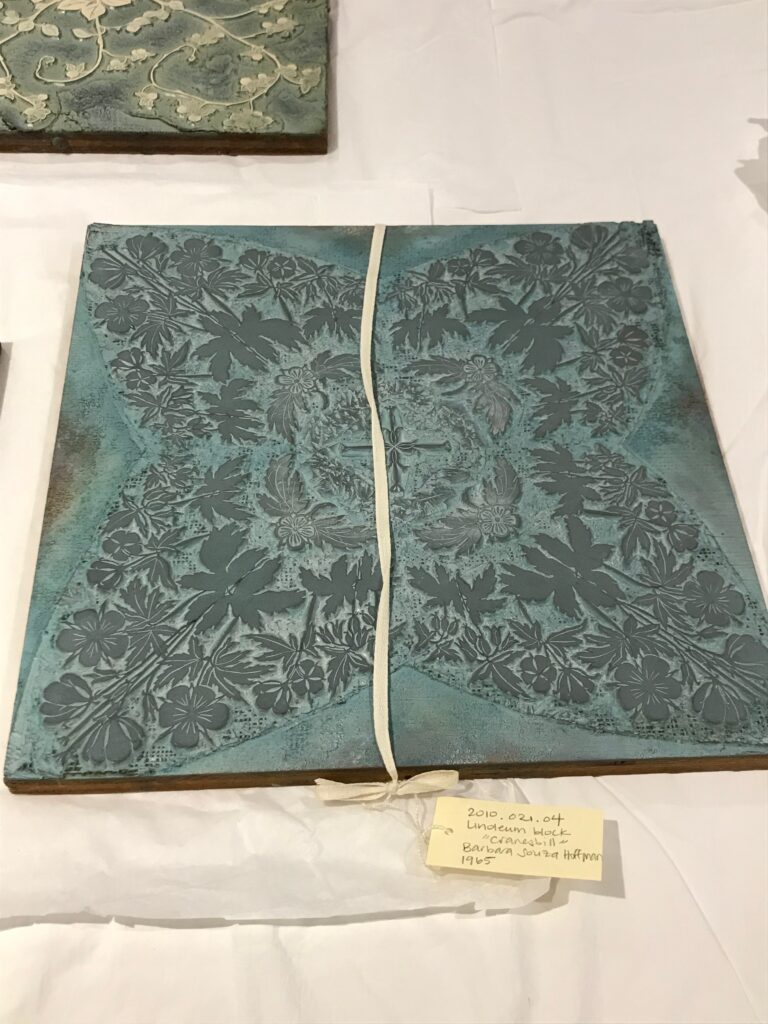

“Cranesbill’ block carved by Barbara Souza Hoffman, 1965.

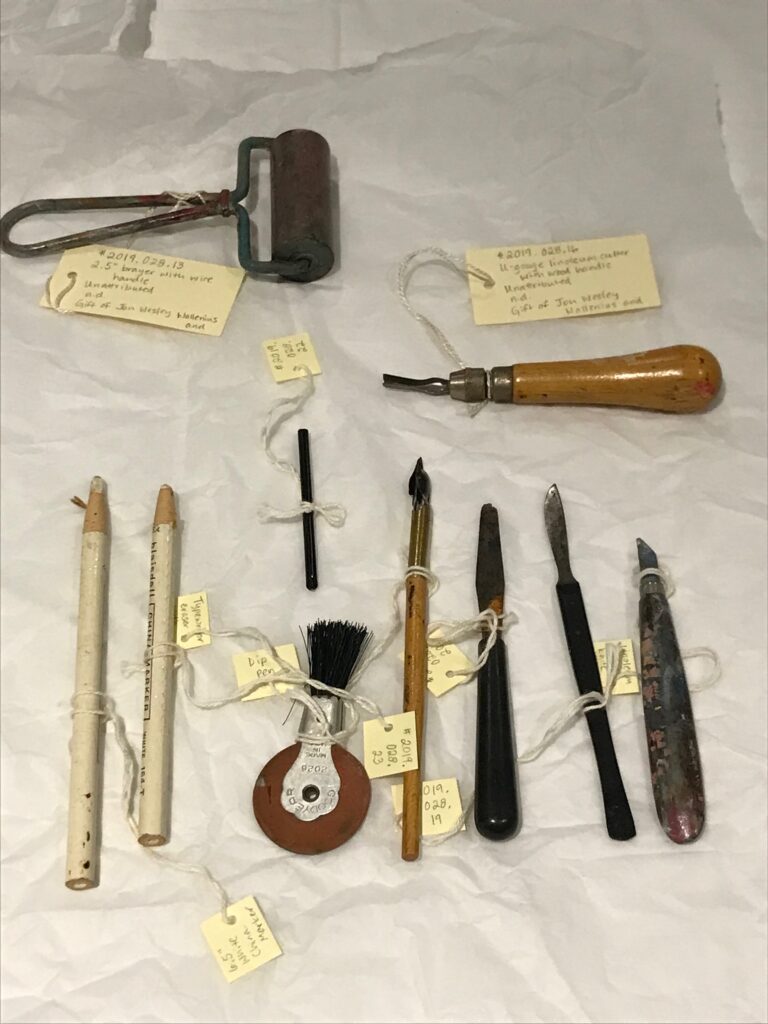

Tools for Carving a Block

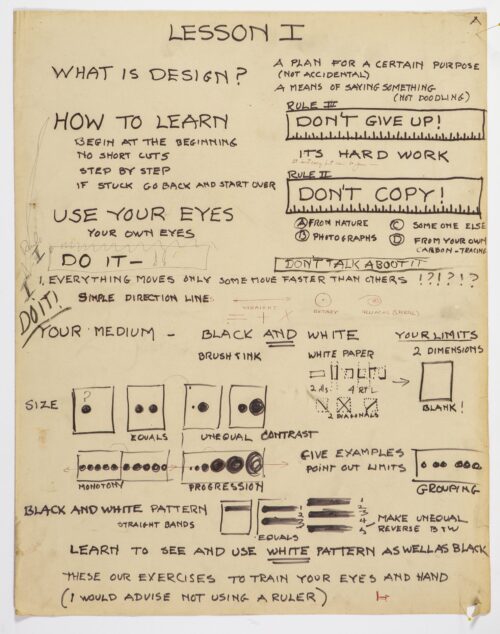

Lesson One of Virginia Lee Demetrios’ Design Course. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives.

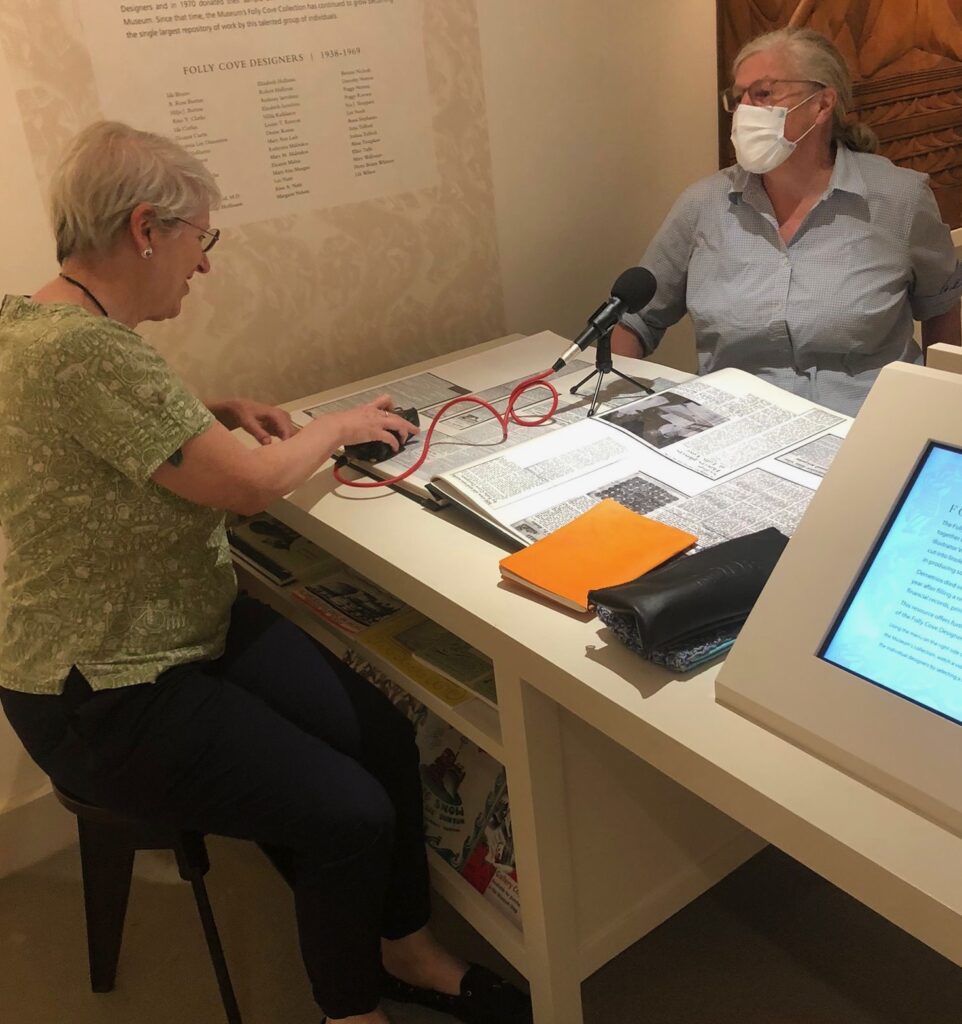

Jo and Martha Oaks

Oliver Barker

Trenton Carls

Strong Threads of a Community – The Folly Cove Designers

What does it take to become a designer? We think of designers as an elite, trained and professional – far removed from us, but here is a story about a little-known group of people in America who worked as quarrymen, and teachers, who were found behind counters in post offices, who ran coffee shops and florists, who were administrators and carers. They were people who did quite ordinary jobs, but at the same time each and every one of them was part of an extraordinary creative community that enabled them – without formally recognised training- to become skilled textile designers producing block printed cloth, that nearly 90 years later is a fresh and original as the day it was carved.

Susanna: There are these times, I think in places all around the world where just the right people happen to be together at the same time at just the right moment when there is something in the air. And that really described Cape Ann in some ways for the 1930s and forties and fifties, there was this incredibly great richness of creativity that everybody revelled in and you just took it for granted.

Susanna Natti is the daughter of one of those designers – Lee Kingman Natti – and Cape Ann, is where Susanna has lived all her life and where this community – the Folly Cove Designers began in the late 1930s. This story belongs in Haptic and Hue’s season, Threads of Survival, because it’s about the way in which the vitality and beauty of these fabrics have stood the test of time – as really good design always does. But there is something else important here – this is also about how strong community bonds, providing creative and practical support, enabled this work to happen and then survive over decades. This deserves respect – but it also has something to tell us about how innovation and excellence happen, whatever walk of life you come from and wherever you live.

Welcome to Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles, my name is Jo Andrews, and I’m a handweaver interested in what textiles tell us about the story of humanity and in particular, what they have to say about the lives of those who make cloth and fabric. Lea Rutledge – a listener alerted me to the story of Folly Cove last year – Thank you Lea – and earlier this year I managed to get to Massachusetts with a microphone in hand:

JA Audio: Cape Ann is an interesting area of America. Think rocky coves, fishing harbours, granite quarries and sailors’ missions. This is a place of tough New England lives. In Gloucester, which is the main town in Cape Ann, there is a big banner on the front of the local museum that says Storms Rage, Gloucester Endures. But it was in this unlikely setting that a unique textile story was born.

There’s a local tale that during the Depression the fishermen of Gloucester decided they needed money to rebuild the harbour, so they sailed their fishing boats down the coast to Washington DC to ask President Roosevelt for it directly – it’s that kind of place. Even today 75 active fishing vessels still use the port. But there is another part to this area as well. This is also a place that artists have come to for the quality of the light and the sea. Winslow Homer spent a couple of summers here painting outside, and the young TS Eliot and his family spent their holidays here – locals call them ‘the summer people’ and they stand in contrast those who make their home here. In the early 1930s a sculptor called George Demetrios, and his wife Virginia who had worked at the Boston Herald as an illustrator, came to Gloucester and settled in the Lanesville district. This was not smart Cape Ann, it was a gritty working-class area that housed quarry workers, many of them of Finnish heritage. They had two children and Virginia began to publish illustrated children’s books under her maiden name of Virginia Lee Burton, books that later became well known such as The Little House, and Katy and The Big Snow, but in the late 1930s she had a problem, as Martha Oaks, Chief Curator of the Cape Ann Museum explains:

Martha Oaks: Virginia Lee Burton realized that the price of paper that she needed to write her books and do her illustrations for the book was very high during the 1930s. And that if she offered design class or design instruction to her neighbour, Aino Clark, Aino would pay her a little bit of money in exchange for the design courses. And it turned out Jinnee was a wonderful teacher and Aino Clarke caught on right away and other neighbours in the Folly Cove neighbourhood realized that something really extraordinary was going on. That if you didn’t have to be an artist, you didn’t have to have gone to art school. if you came under Virginia Lee Burton’s wing, she would teach you how to design.

Jinnee Demetrios had found her mission in life. She’s been to art school for just one year, she wasn’t a trained textile designer, she was an illustrator who’d learnt on the job – but she had strong ideas about what good design was and she proved to be a genius as a community teacher.

Martha: I think it started as design. And so, the basis of everything was understanding good design and where to look for your inspiration. And Jinnee would tell first Aino Clark, and then other people as they joined the group to look to the world immediately around them, that’s where you would find your inspiration, whether it was in your backyard, in your kitchen down at the beach or something like that. And that was her main thrust, at least in the beginning. And I think that they realized in time that they could make the textiles from the designs that they created.

To begin with, people came to Jinnee’s house for classes and they were inspired by her belief that good design belongs to us all and that anyone – if they were prepared to work at it – could learn and implement its principles. Oliver Barker is the Director of the Cape Ann Museum:

Oliver: One of the exciting things about this group is that Virginia Lee Burton, she understood, and she believed that everyone had creative instincts and creative abilities. And through her very defined course, she believed that everyone had the ability to create something that was beautiful and functional for use in their own homes. And to me, that is, that is key in that, that she provided the training and gave everyone a diploma and, and launched them and, and the artists themselves they were inspired by the everyday things around them, the vegetables that they will grow in their garden until the 1960s late 1950s, there wasn’t a supermarket here on the Gloucester mainland. And people grew their own vegetables and had their own livestock. And when you look at the prints, and the designs, they celebrate those everyday activities growing of food, the harvesting of hay, the fishing that did take place here. And it’s completely amazing to me, it encapsulates their lives in this very distinct moment before this area was commercialized.

And this was a revolutionary idea that anyone could go, you didn’t have to enrol in a formal institution, you didn’t have to pay much, and you met your neighbours there, ordinary people like you. Lots of Susanna Natti’s family took up the offer.

Susanna: Well, Jinnee offered a course in design to the local populace. And my mother I think thought, well, why not? She was friends with Jinnee and I actually don’t know when it was that my father took the course as well, whether it was at the same time as my mother or not, but quite a number of my family members took the course and two of my aunts, my Finn aunts, Anna and Saima and one of my uncles, Eino, who became one of the prolific of the designers throughout the course of its existence. And my mother and my father, my father didn’t keep up with it. We have one runner of his, which is very basic, it’s of ants. It’s wonderful, which is, I mean, it’s ants, a totally typical and appropriate subject matter for a designer because they were taught to look at what’s around you take, take what you see. It is wonderful. They’re very busy, the ants. <Laugh>. And so, my mother took the course and I think she thought of it as a creative endeavour, but also as income once the, the designers began selling it, it was a real source of income. So, there was, there was a two-pronged reason for taking it and one was financial and the other was up artistic pleasure.

But this wasn’t a soft option, this was a serious class where Jinnee set homework and where you came week after week to have your work looked at by others, commented on, and above all, where you kept at it. Here’s Susanna:

Susanna: Well, my mother used to kind of laugh that at they had homework they had to do in between their sessions and that only one of the designers Peggy Norton actually ever did all the assignments. <Laugh> but I think that Jinnee’s sort of ethos was that art is, is serious. It’s serious business. I mean, you, don’t approach it with a grim face, but you approach it with focus and passion and that’s how you live. I mean, the way she and her husband George lived was really sort of a work of art because they were so focused on creating it was woven into what they did. And I think she just by example sort of passed that on to the designers and, and I think it would be, would’ve been deeply embarrassing to show up at a session and not have done your work. Oh my goodness gracious! Let’s say peer pressure probably had some, some part in this. And I think she was very good at, at setting expectations both, both by her example. And by saying, this is important. This is what I expect. Let’s see what you can do. And putting that into it too. That’s saying this is a joyful thing. And the very process of doing the homework was so enlightening. I mean, there’s all these little modules that you can put this way, that way to try different sets of shapes and scales and see how they fit together. It’s a little bit like working with a kaleidoscope.

And we have the voice of one of her pupils. Barbara Hoffman Souza was a 4th grade teacher teaching local 9 to 10 year olds. She heard about the classes from a colleague and started going. She died in 2010 but in the early 1990s she was interviewed at her home about what it was like to go to Jinnee Demetrios’ classes:

Barbara: She had a big chart and we would, each have the same type of homework to do because by then we had chosen a subject And, she said, the only way we could really know our subject was to draw it hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of times. In many different ways and so forth. So, this was part of her step by step process in creating a design. And she would put up all of the homework and we would look at it, she’d criticize it, tell us what to do differently. And, this is where you got the idea that the group worked together because they’d offer suggestions for you to go home and try. And I can remember Jinnee’s famous saying, don’t talk about it, do it, what if I, what if I did this? Or what if I did that? Don’t talk about it, do it, do it. You know, she was good at that. She was a wonderful teacher.

Jinnee’s passion for good design and passing on the principles of this are borne out by her original teaching materials which are in the Library of the Cape Ann Museum, you can still see the pinholes where she pinned up her charts. Trenton Carls, the Head Librarian & Archivist looks after them.

Trenton: So what we have out here are large sheets that she would use with the Folly Cove designers to teach them lesson one, what is design? A plan for certain purpose, not accidental, a means of saying something, not doodling. And so each week or each day, or whenever they would meet, they would go over these different lessons that she had. She had homework, things for them to do when they went home and tons of stuff in between. So yeah, it, it’s a really nice collection. And then as you look into some of these other boxes, you’ll get to see some of the work that went into creating the drafts. So, we have each of these different lessons: the circle, and these would be her folders based off of how one would draw a circle and how one would compare it to another size you know, unequal sizes, two part equal subject black, outside white and just really intense attention to detail.

Oliver Barker the Museum Director says the teaching was inspirational:

Oliver: The exercises, the one that we are looking at here that, that it encourages everyone to draw for half an hour making straight lines daily. I, I think it’s a course that we could all benefit from. <Laugh> I have heard that as an individual Virginia Lee Burton had amazing discipline, she was a mother an artist and an author. And so, I know that in order to do everything she did, she got up very early in the day and really grabbed every possible moment in which to create beautiful things for the enjoyment of others

But this wasn’t discipline just for the sake of it There was a purpose behind all of this it created excellent designers. Here were a group of people bringing up their families, working at their jobs, living on the face of it very ordinary lives, but through these classes they developed an extraordinary talent and skill and they put it to use. The classes seem to have begun without any clear idea of producing textiles, but at some stage they decided to transfer their designs to lino blocks and print them onto fabric or paper. Martha Oaks who is the Curator of the Cape Ann Museum spoke to me in their Folly Cove Gallery:

Martha Oaks: So the blocks that they used are plywood with battleship linoleum adhered to the top of it. And the design is drawn on the, on the linoleum and then carved on the linoleum. They would carve with something that almost looks like an Exacto knife. It could take hundreds of hours to carve, which is quite amazing. And some of the designers report using the blocks so much that the edges of their designs would become worn down. And so, they would recreate a block again, if it was something that was very popular and they printed it over and over again, they might need to re carve the block. Virginia Lee Burton created a diploma that she would give to her students as they completed a block, probably their first block. And there’s an example of it on the wall behind you there. And it shows the designer working, working, working. And it’s interesting to point out in the very beginning before anybody had a press the, the inked design would be transferred from the block to the fabric or the paper, whatever they were printing on by turning the block upside down and then jumping on it. And so, the diploma behind you shows the designer at the very end, she puts your block down and jumps on it, which is just wonderful to think. Cuz again, this is in the 1940s when there certainly were presses. And then in time they realized that wasn’t the most efficient way to mass produce designs. And so many designers acquired presses.

This was hard work but what they produced was exquisite. It is quite unlike other design of its time – very much unto itself. Detailed blocks of fishermen smoking pipes and mending nets, winter figures collecting sap from sugar bush trees in deep snow, spring lambs, oak trees and acorns, blocks called Picking Daisies, or Pigs in Clover or Cranberry Bog. The detail and sense of life about them is extraordinary: Here’s Oliver Barker:

Oliver: I think they date incredibly well. We were in the galleries today. And one of the prints that we have on, on display is the Gossips by Virginia Lee Burton. And you can, you can hear the whisper going between them, which I just love. And another wonderful print that we have in the collection is the Finnish Hop. And when you look at it, the vitality of these dancing figures is just, it transports you. So, I think that the, the images themselves and the sentiments that they embody are so relevant for audiences today,

Susanna Natti believes that the design is so good because Jinnee Demetrios taught them to think about what they loved and what they could see around them:

Susanna: I think first and foremost, maybe even before the elements of design, which were clearly the building blocks for what made these so successful, was her, her really adamant statement to them that do what’s around you? I’m always amazed at that, the diversity of the designs and the subject matter, but they’re all based on their lives. A lot of nature, a lot of activities, you know, even bird watching or skiing or something like that or farming and a few abstract ones, which I really, love. And some I think about, Aino Clark’s, it’s antique musical instruments, which, to my mind, is a tour de force of design because of the fineness of the lines that she had to cut, but she had a great love for musical instruments. This is something that she knew and loved and it comes through.

One of my favourites is Aino Clarke’s print, called simply My Friday. It does something startling, something I have never seen before or since on a piece of fabric, it tells a story of what a women’s life was like in 1950. It tracks her day in a series of vignettes from getting out of bed in the morning, dressing, showering, housework, ironing, mowing the lawn, hanging out the washing, digging the garden and playing the violin, it is full of life, humour and honesty. Gradually a system developed where the Folly Cove designers worked mostly on their designs during winter, and sold their work in summer: Martha explains:

Martha Oaks: At the height, you can see there were a lot of designers. I don’t know how many, we say 35 or 40 designers, and they would largely work on their own. They would come together for the instruction and for the critiquing, but this was something they could do at home in their own time, around other responsibilities. And I think that the goal as best I can tell was to have one finished block per year. Now some designers of course had many more than that. If you had no children or you didn’t have another job, you had much more time, but that there would be an opening in the spring or early summer in their barn in Folly Cove. And the new designs that were created over the winter were revealed and shared with the public.

But behind that system was a strong system of peer judgment and hard work as Susanna knew:

Susanna: It was very labour intensive and, and it was also reflected the seriousness with which they took it is that you would create the design you would meet, you would get input from of the other designers. You would make a final design, it had to pass a jury selection and then you would go and, and carefully transfer your design. The old fashioned way, I think, by rubbing, you know, carbon on the, on the back of the design and then pressing down into the, into the block to get the, I mean, it was that in itself was labour intensive and then India inking in all of the places that you were going to be cutting or leaving. I don’t remember, which was the positive space in which was the negative space, but and then painstakingly cutting it out. I just found a block that my mother had started and she was maybe one 25th of the way into it. And she apparently made a, made a mistake. So she had start the entire process over again, because there’s no correcting a mistake when you have a linoleum block and the designs were precise. You couldn’t just fudge it and say, oh, I’ll just change this a little bit. So, I was really glad to find that block, because it did show all of those possibilities and that particular stage. And then once it was cut, then you would have the laborious process of creating each print. And that was not the fun part that was seeing the first one come off the press. Yay. That’s wonderful. It works. But at, at printing number 750, maybe you’re not feeling quite the same way. <Laugh>

But as well as the peer pressure and the hope of a little extra money from the prints there was also something else that kept this group going year after year, design after design, and that was the support they got from each other and tightness of the bonds between them. Susanna remembers as a woman of enormous grace who was kind and funny:

Susanna: I think she was very aware of her body and because she had started as a dancer, her designs also reflect that kind of movement. And her illustrations too, you can see in the gestures and the sweep of people and just the way they’re standing, you know, that kind of body sense. She was she was funny. She had a great sense of humour. She was very warm and she and George gave wonderful parties. Our family would go down on Christmas Eve. They had a wonderful Christmas Eve party for quite a number of years where her studio would house the gathering. And there would be a table out with, you know, smoked hams and turkeys and breads and casserole and salads and desserts. And in one corner there was a little spinet, so somebody could accompany people singing the Christmas carols, and there was such a great spirit of togetherness. I mean, people loved being around each other. It was a very tight group. People knew each other well because you worked together, you lived together, you, you socialized together. And the same during the summer, I would see Jinnee down, at the rocks, we call them the rocks. Folly Cove itself is, a little Cove very pebbly sloping, granite rocks on one side of it and cliffs on the other side. So, Jinnee would go down and, in the summertime, and stretch out in her, her two-piece bathing suit and glistening with oil <laugh> and, and, we would find her down there, my parents and my mother and my brother, and I would go down there to the same hard rocks, you know, not a beach, just spread out a towel. You’re you’re gonna feel the lumps. <Laugh>.”

There is no doubt that the strong community bonds, plus an inspirational leader are what kept this group together and productive for so long – just listening to Susanna makes you almost envious of what they had.

Susanna: And there was so much village feeling to it. I heard a wonderful story from one of my cousins: my oldest aunt and, and her husband and, I think three or four little girls, she ended having five, had moved back to Lanesville from being away for a while. And they all got this ‘flu, they were all very, very sick. And my cousin remembers a knock on the door, the front door, and my aunt opened it and there was Jinnee and George. And the two boys with baskets filled with food for the family. I mean, it was just lovely. And that was how it was, I mean, people watched out for each other. I think I maybe am over-romanticizing it, but there was a real feeling of community.

They sold table linens and curtains lengths and some pre-made clothing and slowly they gathered a reputation and as Susanna remembers it did bring in some much-needed family funds:

It was enough to make it worth it. <Laugh>, but when I think of what people get paid now, I mean, it’s truly stunning what people lived on. And, and I think, you know, perhaps people’s expectations about what they needed for disposable income was very different, too. People, didn’t feel the need to buy a lot of things, plus which the designers were making a lot of their own things, curtains and tablecloths and all those things. But I mean a mat at the time was a, a dollar and 15 cents which is stunning for the amount of labour that went into create one mat. and now it kind of blows my mind, that was not considered you know, an outrageous price at the time to be charging for that. I think between my mother’s income as a writer and as a designer she really felt like she was pulling her weight in, in the marriage. And I think that was really important to her.

And because this design was good the Department Stores came calling – here’s Martha:

Martha Oaks: During the 1940s they caught the attention of some of the biggest department stores in America and were able to sell table linens in some cases pre-made clothing that they made with the designs on them. And it just caught people’s interest. It’s hard to know why. But they were quite successful. And from what I read, they could have gone further if they sort of had turned the process over to say Rich’s department store and let Rich’s mass produce them, but they didn’t want to give up control. They wanted to be the ones who printed and had sort of quality assurances about their work, but something about their work just caught people’s imagination. And this scrapbook in front of us here has numerous articles that every summer when they would have their opening, people would flock to the barn and to see what new designs had been created.

And these designs have a charm and a simplicity of their own. Something that endures in them and stands outside the cycles of fashion and style, as Martha knows:

Martha Oaks: I often come in this gallery and I find people here draped over these computers, looking at all the designs. I can walk away. I come back 20 minutes later, they’re still here. So I’ve thought a lot about why it is that people are so enraptured with them. There was a woman in here this morning. Oh, look at these teapots, look at these teapots. And maybe it’s because they’re just very simple in their design. They’re everyday things that we all see in our lives. I look at them and, and maybe visitors do too and think I could do that. I could draw that teapot or that apple and I could carve a block, maybe, they’re very approachable. And they’re very simple when you look very closely, and yet when they’re printed over and over again, four or five blocks when it’s a, a block or two or three blocks with multicolours, it all of a sudden becomes unbelievable, but there’s something just very every day and ordinary. And I think it’s has largely to do with the subject. Somebody dancing, somebody ironing, somebody riding a bicycle. But they do have great appeal to people.

After 30 years of running Folly Cove Designers Virginia Demetrios died in 1968:

Martha Oaks: She died of lung cancer. And the group decided before she passed away, that when she went, they would disband, they would stop printing materials. The designers took all of their things home with them. But they decided just stop. And some of the printers, some of the women continued to print a little bit on their own, but they largely stopped by then many of them were getting on in years. And because Virginia Lee Burton did not continue to offer her design class right up through the end of her life. There was not this next generation of people coming. Although there have been artists and still are today who are very inspired by the whole process and do do block printing sort of in the same tradition as the Folly Cove designers, but they just decided that they would stop and they all agreed they would stop.

Susanna says her mother, Lee Kingman Natti, was ready to call it a day:

Susanna: And when Jinnee died in 1968 the designers disbanded at that the following year and people often ask me well, why didn’t they continue? Well, I mean, why did they break up? And, and there were really two reasons and one was that Jinnee was no longer there to give the course, so that you couldn’t bring in new designers and it was a requirement to be a Folly Cove Group designer. You had to take her design course. But I think they also were all getting a little bit older, most of them. And they were tired. It was hard work. My mother was really ready to say this has been wonderful. But now I’m happy to hang up my blocks and that’s where they are. They’re hanging on the walls here in our house. <Laugh>.

And that is how this bright flowering of design came to an end, and here is the answer to the riddle of why the magical work of Folly Cove didn’t enter the design vocabulary of America and isn’t better known. The designs and the fabrics are still here, you can see them and marvel at them, but because the designers didn’t want the Department Stores to mass produce their work, and because they simply stopped when Virginia Demetrios died, and agreed that no-one else could print from their blocks, their work has remained almost hidden and their story untold – even though the designs themselves still breath life. Now that is beginning to change with a new exhibition at the Cape Ann Museum, and in the Archives of the Museum there is also a gem that might still be published – it is the draft for a book that distilled all of Jinnee Demetrios’ hard won knowledge for her design courses: Here’s Trenton Carls:

This is interesting to me because during the time in which she was teaching this and continuing on for over 25 years, she was working on a publication called Design and How! Design and How was never published. It remains unpublished, it was never fully completed. But we have probably about six or more mock-ups about how the book was going to look about, you know, ideas she would tip in and add in and get closer and closer to that final design. It’s a really elaborate and beautiful publication.

The Director of the Museum Oliver Barker believes it could be possible to publish it.

Oliver: We have to find the right scholar who would be prepared to take that on. And obviously we want to work closely with the family too in honouring her intentions. But there is, as Trenton was sharing, so much great material here that there, I hope in the future, is the possibility of completing this and making it more publicly accessible.

Susanna Natti, Daughter of Lee Kingman Natti, says it took a move away from Folly Cove for her to understand how special the place was:

Susanna: I took it for granted growing up, that this was how every place was <laugh>. And then I went off to college and my roommate said after she’d gotten to know me, but she said, do you have any idea how unusual this place is that you grew up in? And at that point it began to dawn on me <laugh> but I think there is, there really are two parts of the stories of of the Folly Cove designers. And one is the work and how well it stands up even without that context. And I think the second part is about the, about the community, the strength of the bonds, the caring that went on the creative support among all of them. I think the fact that so many of the designers were women and with independent lives and, and very interesting characters was also really important. I think the fact that it is now part of the Cape Ann Museum and the Cape Ann Museum has recognized that they have an important place in the art and culture of Cape Ann means everything to me, it was extraordinarily important to my mother and she was very glad to see that happen.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Haptic and Hue, and a huge thank you to all at the Cape Ann Museum for being so generous with their time and insight. Thank you also to Betsy Chittenden who acted as my Chauffeur and Path Finder on this trip, and with whom I shared one of the finest Lobster Rolls I have ever eaten. If you would like to see pictures of the Folly Cove designs and the designers, the tools and blocks they used, or read a full script of this podcast, you can find it all on Haptic and Hue’s website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen. Haptic and Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee. If you’d like to contribute you will find the button on our website at www.hapticandhue.com.

Haptic and Hue will be back on the first Thursday of next month with another tale – this time about re-uniting Japanese families with long-lost material possessions from relatives who perished in the Second World War. Meanwhile instead of a poem, I will leave you with Virginia Demetrios’ introduction to her unpublished book of design. It has something to tell all us of who work at acquiring a skill with our hands. She says: “This book is a primer for the beginner, and a primer for the designer, particularly for the designer-craftsman. It is an elementary course in design based on practice rather than theory. No previous training is necessary, and requirements are few…a desire to learn…a willingness to work…time to practice and an open mind. It is simple but not easy, it is a beginning with no end, and the more you learn the harder it is. You will get as much out of this book as you put in, because this a way that works if you work too.”