This episode could not have been made without Rebecca Devaney, who tells her story of becoming an Haute Couture embroiderer. She trained at Ecole Lessage.

You can see photos of her and her work below. She wrote a blog about her training. You can find out more about her textile art practice, residencies, and research at: www.rebeccadevaney.ie

She can be found on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/textile_tours_of_paris/ or https://www.instagram.com/rebecca.devaney/

Rebecca runs Textile Tours of Paris, which is a wonderful walk around a different side of Paris.

Thanks also to Marie Berthouloux for sharing her insights with us. Her studio is called Ekceli, where you can see examples of her goldwork as well as the skill and knowledge she brings to this. You can find her on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/ekcelimb/

And to Frederique Crestin Billet, who founded and runs Maison Sajou. Frederique is a historian of haberdashery and her website is full of wonderful detail about the history of these essential items. https://sajou.fr/en/ Maison Sajou is on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/maisonsajouofficiel/

Haberdasheries in Paris.

Ultramod is the oldest haberdashery in Paris. Beware! Once you enter you may never leave. It doesn’t have a website, as far as I can see, but here’s a blog about it. https://www.rebeccadevaney.ie/blog/2019/6/3/ultramod-the-oldest-haberdashery-in-paris

It is, though, on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/ultramodmercerieparis/

Au Ver a Soie is not far away. They speak English and welcome visitors. Look for their threads on Etsy and at good haberdashers in most European countries. They too are on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/auverasoie/

Rebecca Devaney, embroiderer

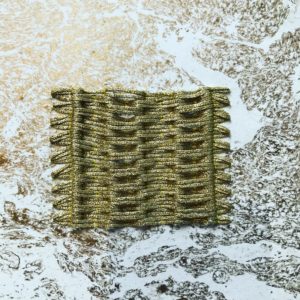

Rebecca’s Ecole Lessage sampler

Rebecca’s Ecole Lessage sampler

Marie Berthouloux, goldwork embroiderer

Goldwork by Marie Berthouloux

Preparing an exhibition piece

Sample

Goldwork by Marie Berthouloux

Work in preparation

Frederique Cresstin Billet at Maison Sajou

Handmade Sajou monkeys

Bias binding, Maison Sajou

The oldest mercerie in Paris

Ultramod

Ultramod buttons

1950s Duchesse Satin

Ultramod

Silk velvet Ribbons

Au Ver a Soie

Silk thread

Au Ver a Soie

Script

Stitches in Time

Unless we live in Paris, right now we are shut out of its rivers and bridges, away from the ancient bulk of Notre Dame, the little flower markets, and the neighbourhoods of the old city with their bars and pavement cafes.

This is the Paris millions of us know, but alongside it, there is another Paris, not so easily seen – a city that is home to the sound of sumptuous fabric being unrolled, the snip of scissors and the flash of a thousand needles pulling silk threads in the painstaking business of making elegant garments in the ateliers of the French fashion houses.

Across France, the modern fashion industry employs around a million people and contributes a big chunk to the country’s economy. But what interests me here is just one section of it – Haute Couture, custom made clothing that is constructed by hand from start to finish.

I will never own a garment like this – I don’t have the money or the inclination – but the story of the skilled makers who sit behind the seams of the garments we see on the catwalks and in the fashion magazines is fascinating: the feather artisans and sequin-makers, the weavers, corsage creators, button makers, seamstresses, lace-makers, and the embroiderers.

Rebecca:

I got to work with beautiful materials and I got to work on wonderful gowns for the Cannes film festival, the Met gala ball. And I got to work on pieces of embroidery that I personally loved which isn’t necessarily the case. You have to work on things that you don’t think are nice or wouldn’t be to your taste. And so that I certainly was learning the techniques and that was very enjoyable for me as an artist or a craftsperson.

Welcome to Haptic and Hue’s first series of podcasts, which looks at textiles of all kinds down the centuries and thinks about the role they play in our lives. I’m Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver and a broadcaster. Haptic means the feel of something and Hue describes the pure spectrum colours.

This episode explores the hidden hands behind Haute Couture and looks at how it fostered some of the most skilled textile artisans in the world. It also thinks about the way the system has developed and how it is changing in the face of modern tastes and pressures.

To make it I went to Paris in March and visited workshops, talked to artisans, designers and specialist shop owners. It was a privilege to do this in what turned out to be, in Europe, the last week of our old lives.

The secret foundation of Parisian style and elegance is its haberdasheries, known in French as a Mercerie and in American English as a Notions shop, a word that doesn’t begin to do justice to the glory of these treasure chests of fabrics and feathers, buttons and trimmings.

The best Haberdashers are in Paris’ second arrondissement, in a district north of the Palais Royale, called Le Sentier. This is the old fashion district, which once hummed with activity, today the ateliers have moved on, but the haberdasheries remain.

Shops like Ultra-mod where you can choose from its stock of 50,000 buttons, smooth its collection of 1950s Duchesse satin and ruffle vintage silk velvet ribbons beneath your fingers, or cross the street and enter its Chapellerie, a specialist shop that sells hats and all the trimmings to shape and decorate them.

Au Ver a Soie is not far away, it’s on the first floor of an old building just off the Grand Boulevards. You have to be determined to find it, it specialises in pure silk embroidery thread. If you enjoy colour, which I think most of us do, then this place lifts your heart as you open carton after carton of thread collections on tiny wooden spools in graduated shades and tints.

These are glorious places but they are also important places because this is where couture was born. In the 18th and 19th centuries. Paris’s haberdashers were fashion’s first stylists. The relationship between a Haberdasher and her client was an intimate one. The haberdasher had to know exactly what was in fashion, what the latest trends and colours were, and provide advice on how an old garment could be updated with new trimmings to make sure that her customer was appropriately dressed for the occasion- whatever it was. My guess is that rather like hairdressers today, haberdashers knew a lot of secrets.

It was on the strength of these expert suppliers that Charles Frederick Worth, an Englishman opened his haute couture atelier in 1858. He was known for his lavish use of fabrics and trimmings, and his attention to fit. He also pioneered a system of showing a range of garments on live models at the House of Worth. Clients made their selection and had the clothes tailor-made in his workshop.

By the end of the 19th century, this system had spread far beyond the small courtly and aristocratic circles of Paris and wealthy women were coming from all over Europe, and beyond, to have their clothes made in these ateliers.

By 1900, more than 170,000 thousand needlewomen, known as the midinettes were employed in Paris, mainly in Le Sentier. They were a formidable force.

Working-class women from Montmartre and Belleville who were employed by the ateliers and earned a living for themselves. They had their own dining halls and fought successfully for the right not to work on Saturday mornings but instead to have it off.

The demand for fine French textiles, ribbons, lace, artificial flowers, buttons, thread and everything to supply this industry spawned a supply chain of quality manufacturers across the country, suppliers, who because of couture, have survived in France in a way in which they haven’t in Germany, Britain or America.

Frederique.

I think we have very, very less than we had before, but I think that because of Haute Couture, you know, we still have people working. So for example, in the factory where they make my ribbon, my woven ribbons in the place where they are, I don’t know, 50 years ago, they were perhaps 50 or 60 or a hundred manufacturers. And now they are two, three, four, you know, but we still have a little bit.

Frederique Cresstin Billet is a Historian and collector of haberdashery. She has her own shop called Maison Sajou which specialises in traditional French-made fabric, threads, ribbons and trimmings.

Frederique

Well, first of all, it’s because this is our heritage, so French heritage. So it’s important for me. I think there is a quality and a know-how, but I agree, perhaps there, was the same, And I’m sure there was, the same knowhow in England and in Germany and, you know, but they forgot it. And now in France, we still have not so much, but we still have people producing, you know in Normandy where we used to produce pins and needles, we still have a manufacturer making that, you know, so this is perhaps a defense. We still have here some little things and I try to help them to, to stay, to still working.

Frederique has helped revive a famous French brand of thread, Fil au Chinois some of which is made with machines dating back to the 1890s, Ribbon manufacturers in St Etienne have re-started ancient weaving machinery for her. Her shop attracts buyers from all over the world and her determination to conserve French heritage helps keep around 30 suppliers going, suppliers using old methods with modern materials. She is clear that this is doesn’t make her a rich woman.

Frederique

Only passion, you know, passion, because if I had no passion, I think I will not be here anymore. You know, because I don’t earn a lot of money, but I have so much nice people working with me and, you know, and I, I can create because my, my, the reason of my life is this is to create, so I create every day something,

Frederique and the other haberdashers supply an industry that has changed greatly in the past 100 years, but which has had at its core skilled craftspeople, people like Rebecca Devaney who we heard at the start of this podcast:

Rebecca

So from when I was 18 and 19, I was always fascinated by the history of haute couture fashion in Paris. And I had a fairy tale dream of coming to Paris and learning how to do haute couture embroider.

Rebecca took a teaching job in the Gulf to save the money so that she could enroll for her professional qualification at France’s top embroidery school, Ecole Lesage, set up by the family who founded Maison Lesage, the top supplier of embroidery work to the French fashion industry. It was tough.

Rebecca

Yeah. (Laughs) in short that was very hard, you had of 150 hours class time. And so I did my qualification in six months on a turn I found out later that I could have taken a lot longer to do it, but I was under time and financial pressure. So I did three, three hour classes per week through French. And in the beginning I would have maybe six hours of homework each evening. And then by the end and I was doing, I’d say 14 hours embroidery per day, 14 to 16 hours per day.

JA: I should think you wanted to burn it at the end of that.

Rebecca Oh no, I’m going to be buried in that. That’s my funeral shroud (laughs)

Her sampler is a thing of wonder, in pink, blue and gold, studded with detail, precise in its execution and in the lavish application of sequins, flowers, feathers and tiny stitches. If you’d like to see it there are pictures on the Haptic and Hue Website on the page for this podcast. Everybody on the Lesage professional course does the same standardised sampler:

Rebecca

It’s 40 centimetres by 60 centimetres, it includes about 29 haute couture embroidery techniques in a huge variety of materials, like passementerie, beads, sequins, and threads. And I suppose it’s like a masterpiece like that, that piece, it’s like a C it’s like a visual CV. Like if I were to bring that to an interview and people would know that I can do these techniques. So it’s a visual kind of summary of all the techniques that I learned

As she came to the end of her studies she asked her teachers what the next step was to become a professional embroiderer.

Rebecca:

And they were saying that really, since the 19th century, the techniques for Haute Couture embroidery haven’t changed and they’ve remained the same. What has changed is the materials that you’re working with. And so they were saying the best way to gain experience and to broaden your knowledge is to start working in the ateliers, the haute couture ateliers. because you get can be exposed to all these different ranges of sequins and beads and things like that. And for me, I love the idea of that, of seeing all these materials and that I wouldn’t necessarily have the opportunity to buy myself, I would necessarily be able to afford them and, and to learn how to use them at the same time, because embroidery is full of hints and tips and tricks that you learn as you go.

There are three recruitment agencies in Paris that specialise in Haute Couture embroidery Rebecca signed up with all of them and was sent out to work in a number of well- known ateliers.

She found the work satisfying and interesting from a craft point of view and her love of embroidery still shines out of everything she says, but there is a big drawback in today’s system:

Rebecca

The cons would be that it was for me, a very stressful period financially, it is contract work and which depends on the seasons and fashion, the rhythms of the fashion season. And it also can change season by season in embroidery can be in or embroidery can be out and if embroidery is out, it means you won’t have work: And also the rates of pay were a lot lower than I expected. So working with the recruitment agencies and an embroidery working for the major fashion houses in Paris will be paid between 12:50 and 13 euro an hour. And in France, they work a 35 hour week.

JA So that’s about $15 an hour.

Rebecca That’s $15 an hour. And that’s gross. That’s before the French tax system and the French social charges are taken out, which is about between 40 and 50% and you’re living in a capital city. And so financially there was a great strain. And the other thing to bear in mind is that you might have very intense work for two weeks or three weeks. And then between periods, you sign up with unemployment services and the unemployment system in France works in a way whereby you are given 50% of what you earn. So with the unemployment service, because I was being paid 13 euro an hour unemployment was paying me 6.50 an hour in periods that I wasn’t working.

The gig economy has well and truly arrived in Haute Couture. The houses have anything between two and around 15 or 20 staff embroiderers, for the rest – they bring in freelances on hourly rates when they have the work.

Rebecca

Yeah, they have developed a system whereby young embroiders who have gone through their training at Ecole Lessage or in the national embroidery schools in France. They actually don’t have the time. They don’t have the opportunity to train in their craft. And previously it was said that embroiders needed one seven years working in the studio like any other craft. And before they had really gotten their wings and they had had a broad exposure to materials to techniques that they were able to work independently. But now with the system of contract or freelance work, you don’t have that time in the studio. So the embroiders that I would talk to who have, you know, 30, 40 years of experience are just a treasure of savoir-faire, and they’re really, they really lament actually, and the fact that they can’t pass down their skills.

I think it’s a very short-term approach. Embroiderers will talk about how it’s much, but the fashion industry has changed massively. And that has a knock-on effect for the craftsmanship that goes behind haute couture work. And so in the short term, there might be very high profits for certain people at the top of the, at the top end of the system. But it means that in the long term, they won’t have the craftspeople to do the work in France.

And already the industry is seeing an exodus of trained embroiderers like Rebecca, who now teaches embroidery and runs her own textile tours of Paris.

Marie Berthouloux is a goldwork embroiderer who works in a small studio in Paris. She started off by studying fashion but then as a post-graduate looked around for a craft to specialise in, and found her inspiration at the Arts School in the City of Rochefort.

Marie

Rebecca translates: So the reason that she loves gold work is because the material is very very interesting, it very supple and flexible but it’s also very fragile and can break very easily. Also, Rochefort is the only place in France where she could study goldwork embroidery and that was very rare very exceptional and that’s what intrigued her most.

So what was fascinating for Marie was that this technique was generally used for ecclesiastical or military embroidery, but when she was in school, they were encouraged to break the materials which were generally very precious, to play around with them and to create contemporary pieces.that were inspired by traditional work.

In the old days, Marie would have gone to work for an Haute Couturier but not now, instead, she has set up her own small company and takes commissions from architects and interior designers to create one off bespoke pieces. This is a new enterprise and Maire is still in the phase of sampling and developing a client base. Her work is glorious, fine, and intricate, and she incorporates the throwaways from the luxury textile industry where she can. She’s not sure she can make a living doing this, but it’s worth a try.

Rebecca translates: One thing is that embroidery is generally thought of as being very fragile and very delicate, but on the contrary embroidery can last for centuries and there is also the feminine side whereby embroidery can have negative connotations because its seen as a past time or a hobby of women. So in France possibly around the world, there is a tradition of embroidering at night, where you would be repairing or adding detail to your clothes, so it’s not at all seen as an area of craft or fine art, its seen as very utilitarian

But there is another deeper reason why Rebecca and Marie and countless other embroiderers like them no longer work in the ateliers. The label on your Haute Couture garment may say Made in France but particularly if it is embroidered that’s no longer likely to be entirely the case:

Marie

Rebecca Translates: Yes, that’s the truth. Actually, the prototypes or sampling is done in France but the production stages are done abroad.

JA: And the clients don’t know this?

Rebecca: Marie feels that everyone is aware that the production work is done abroad, perhaps everyone in France, however, it doesn’t affect sales. Because that’s the way the market is going at the moment.

Jo Its a high price to pay for something that says Made in France, when it isn’t made in France.

Rebecca; Marie thinks that the clients buy the label and the ambassadors of the label, they buy into the image of whoever is working as the ambassadors for the label, rather than buying the craftsmanship.

Even the Senate – the upper house of the French Parliament which had called a meeting with the artisans the week I was there – was surprised to learn that the Haute Couture houses were sending work abroad.

Rebecca translates – this is exactly what came up on Monday, an embroiderer who works in fashion said this, and the Senate wasn’t aware that the HC houses were having their embroideries done abroad and that they were still eligible for the Made in France qualification.

Rebecca explains how the system works:

Rebecca

And so the first prototype of a sample will be done in France. And so that kind of, that creative process to kind of over and back of adding these beads or these pearls or these stitches, once the client has agreed, they might decide that they need 10 or 20 or 30 or 40 pieces. That production stage is where it was previously done in France. And as you can imagine with embroidery for 10 or 30 or 40 pieces in just one house would involve an awful lot of work, and an awful lot of employment. It’s sent to India. Yeah. I know that this is a huge or a thriving Haute Couture embroidery industry in India. There’s also one in North Africa. And so what happens at that stage is that the sample or the prototype will be sent by somebody from the embroidery studio in France, to their collaborators in India and where the production stages will be completed. And then again sent back to France and in an extremely short turnover period

JA At a very economic price?

Rebecca: At a very economic price yes, but with very similar standards of quality.

I wonder if this matters as long as the Indian or North African embroiderers who tend to be men are paid fair wages, They deliver high quality, and after all a number of the embroidery techniques originated in particular India.

Rebecca

I know that the French embroiderers are very adamant that you can tell the difference that there’s a certain finesse or kind of standard of finish that is lacking in the Indian embroideries. But in conversation with the head of the embroidery studio Vermont, who, you know, collaborate with Indian embroiders, she would say that very much so, the standard is the same, and that they’re very proud to be working with the Indian Haute Couture ateliers.

JA: And yet when people buy Haute Couture that says made in Paris or made in France, they have an expectation that everything is done here?

Rebecca:

Absolutely. My understanding would be that haute couture is synonymous with Paris and on a whole culture was born here in 1858. And France continues to very much when you speak of Haute Couture, you think of France and you think of Paris. I think the discernment of the customer perhaps has changed over the decades and over time and where previously there may have been an awful lot of focus on the craftsmanship and the skills and the creativity behind Haute couture. And now there is an awful lot of focus on the labels and the brands. So, customers are now more buying into a brand and buying into a label, and they may not be asking questions such as where is this made or there they’re presuming.

And it also means that little by little the skills and the specialist knowledge that made Haute Couture stand out are leaving France:

Rebecca

What embroiders would say is that previously they were asked to work with a much broader variety of materials and that when they would come into the studio, they never knew what challenges they were going to face. And for them as craftspeople, that was fascinating problem solving, finding a solution. Beads are made to the design of the embroidery designer, the artistic director at the specialist sequin makers in Paris. And so the client and the artistic director might decide on a certain kind of sequin and, and it had never been made before. And then it was up to the embroiderers to figure out how to use it. So they would say the embroiders would say that there was an awful lot more creativity and excitement and buzz in previous times. While the quality has remained the same for them It’s not as challenging or interesting.

Rebecca believes that in time this will signal the end of the fairy tale:

Rebecca

I know a lot of my colleagues who I would have worked with, just can’t afford to continue working as embroiderers, it’s a way of life that involves a constant manage of stress and financial anxiety and you will find in Paris a lot of embroiders working as waitresses. And those who have a real love of the heritage of Haute Couture in France, including particularly if you speak to people who work in the recruitment agencies, they are very aware that the system that has come into place now will actually lead to the demise of Haute Couture because it is so focused on profit and rather than craftsmanship.

And while some of the large Haute Couture houses make efforts to train new young craftspeople, and to kind of incubate them on to, you know, begin systems or relaunch systems of apprenticeship. It’s, it is seen by some, as a token gesture, not enough., and I’ve worked in studios where you have, you know, tailors in their seventies being the best tailors being flown in from Turkey and other places in Europe to work on collections because there’s nobody coming up behind them. And the tailors themselves will say, you know, when we were in our late teens, early twenties up into our thirties, we were still doing apprenticeships and there is nobody here taking that places.

Marie Berthouloux puts it another way:

Rebecca translates: Marie believes that each country has an obligation to preserve the craftmanship or the heritage that was born in that country and that it’s very important that these crafts are supported in the countries and that they continue in those countries. Marie is well aware that in India and in other countries around the world people are very gifted in embroidery but in the same vein, she believes that French embroidery should be preserved in France.

Rebecca: so its also the consideration that goldwork embroidery can be seen in Spain or Madagascar or France, the technique stays the same, but it’s the manner in which the technique is interpreted or expressed creatively. This is what is interesting and this is what gives another regard and this is very much worth preserving as well.

There is a tremendous sadness that an era of respect for French craftsmanship and excellence is passing, but at the same time both Marie and Rebecca still find joy in the skills themselves, as they find new ways to earn a living

Rebecca:

It is really sad because, you know, despite the stress and the anxiety from the financial end, the embroidery work is absolutely beautiful. And it really needs the best of materials, really fascinating techniques, and just, you know, sometimes it can be breathtaking when you look at the embroidery particular in museums and galleries and things like that, particularly, you know, I always loved, I always thought it was beautiful again, once I’d studied it, And I knew how long it took to add each bead, it really just would take my breath away,

This episode of Haptic and Hue was written, narrated, and edited by me, Jo Andrews. Many thanks to Frederique of Maison Sajou for sharing her passion for Haberdashery, to Marie Berthouloux of Studio Ekceli for showing us goldwork embroidery at its best, and most of all to Rebecca Devaney for her skill, insights, interpreting, good humor, and willingness to share a glass of wine with me.

You can find out more about each of them with photos of their work and links to their own sites at www.Hapticandhue.com forward slash listen. All the haberdashery shops I mentioned have good online websites and ship around the world, more details are on the website. Your bank manager will not be best pleased.

You can also find show notes there, where I provide a complete transcript of this podcast and a list of resources and background reading that you might enjoy. You can also sign up there to get these podcasts directly into your inbox and have a chance to win the textile-related gifts that I give away with each episode. You will also find blogs and other information about textiles and Haptic and Hue there.

Next time, we stay in Paris to meet the woman who is the happy owner of the world’s largest collection of fancy yarns. Eve Corrigan has the yarn stash to end all yarn stashes, 900 tonnes of it. Find out why she needs it and what she makes it with it, next time on haptic and hue. Thank you for listening!