Episode #63

Jo Andrews

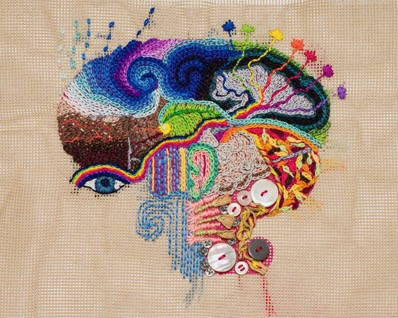

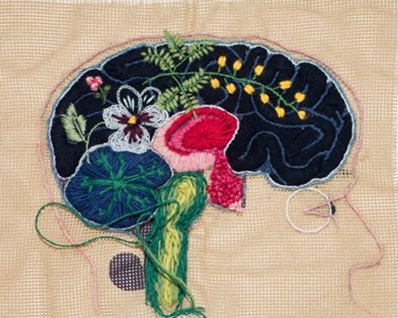

About ten years ago a doctor in The Netherlands started what sounds like a simple and practical project. She sent off embroidery kits with a print of the human brain on them and asked participants to stitch a picture of a brain. The results, captured in recently published book, are glorious, with a variety of stitched, fringed, appliqued, woven, beaded, woollen, and embroidered brains.

Those who took part in the Stitch Your Brain project were being asked to do something complex: to use their handcraft skills to think about their brains and what happens to them when they make. It brought into sharp focus the incredible relationship between our hands and our brains and how we use them together to practice or learn a new textile skill and use it with ease and enjoyment.

Notes

Monica’s Auch’s website with more on Stitch Your Brain is at https://monikaauch.com/research

We will be giving away 9 kits of Stitch your Brain with this month’s episode of Friends of Haptic & Hue that goes out on October 16th. www.hapticandhue.com/join

If you want to stitch a brain yourself you can order a kit at: https://cargocollective.com/stitchyourbrain/Order

For those in Europe you can find her book at https://www.japsambooks.nl/products/stitch-your-brain

For those elsewhere it is also on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Monika-Auch-Stitch-Your-Brain/dp/9492852772 or you may find it in good independent textile bookshops.

You can also find Monika on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/monikaauch_weeflab/

Eva Andersson Strand is at The Centre for Textile Research https://ctr.hum.ku.dk/ which is on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/centrefortextileresearch/

Mark Schram Christiansen is in the Dept of Psychology at the University of Copenhagen https://research.ku.dk/search/result/?pure=en%2Fpersons%2F228267

Monika Auch

Stitch Your Brain

BRAIN 48 by Marga Lansink

BRAIN 80 Wendela van Popta

BRAIN 69 Regula Müller

BRAIN 28 Gesine Hackenberg

BRAIN 89 Inge Bosman

BRAIN 68 Raija Jokinen

BRAIN 98 Maxine Derksen

Mark Schram Christiansen

Eva Andersson Strand spinning while being monitored

Woven Tapestry of Eva’s Brain While Struggling With Spinning. Made by Ulrikka Mokdad

Script

The Intelligence of the Hands & The Creative Brain

JA: Monika Auch is an extraordinary person: both a trained doctor and a weaver, she set out to answer a question that down the centuries has perplexed the great philosophers:

Monika: Well, I hoped to find out what really is creativity, and if you can actually measure creativity. A lot of people had been trying to pin down what is creativity, but I know from doing medical research that you just have to frame your question. So, what really interested me is how hand and brain cooperate in creativity.

JA: What I like about Monika is that she approaches this from an utterly practical angle, but also an artistic one – this is a marriage between her scientific and artistic backgrounds and because of that she works in a different way.

Monika: The un-meditated way I worked, which was a mixture of intuition, but as well just making, and of course, technical and material knowledge, which I just already had. So that again, made me thinking about that, that combination between my brain, the knowledge, the memory of materials, and what my hands were doing. So, I decided to look into this much more.

JA Welcome to Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews, a handweaver interested what textiles tell us about ourselves and our communities, stories that go far beyond the written word and often explore the lives of those who had little or no voice. This episode is about one of the great questions that lies at the heart of being human – our creative intelligence. This is not the kind of intellect that we can test for on any kind of exam or IQ assessment, and yet it is the sort of tacit knowledge that has been fundamental to our survival down the long centuries of our presence on earth. Trying to understand it though is not easy. Preparing this episode at times reminded me of being in a university library many years ago and reaching for a philosophy text book to find another perplexed student had got there before me and written in the margin: “Man this is so far out it is coming back” I will do my best and Monika is a reassuringly practical guide:

Monika: I come from a, a working-class background and very strong women who always kept everything going. So, instilled in me was the idea that you have to be able to earn your own livelihood and as well to explore your potential. But while I was studying medicine, these five years of theory are really tough. It’s a lot of book knowledge you have to put into your head. And I really, really missed to do something with my hands. And this friend of mine said maybe you should take up weaving. And I, I laughed because at craft at school, I always just about passed because I made these really weird things that my teacher did not approve of. So, I was absolutely working outside of the box all the time. I didn’t really care about that. So, I thought weaving really <laugh>, but just for a laugh, I started and I absolutely got hooked on weaving. So, I went on in two different ways to study tissue in a medical <laugh> in a medical setting, and as well in a textile setting and I thought there were quite a lot of similarities.

JA: Monika had a medical career specialising in women’s health, and she says that her hand skills served her well.

Monika: You had to perform sensitive procedures, but if you have good hands, it, it helps the patient and yourself. So, this sort of went parallel to each other.

Jo: So, you were using your hand skills both in the medicine and in the weaving?

Monika: Yes, absolutely. This was the time before we had all the devices to do medical investigations. I mean, we did not have MRI scans then. We, we had CAT scans and this kind of, or x-rays or whatever. So, you had to really rely on your hands and your senses as well, your sense of smell sand hearing and palpating which I really, really enjoyed as well, and I enjoyed stitching up people. That sounds a bit gross, but I mean, it’s nice to, to do neat work Yeah.

JA: Later she took a four year degree in textiles in Amsterdam and decided to try to combine her scientific and creative backgrounds and design a research project to see if she could measure, or at least understand more, about creativity and the relationship between our brains and our hands.

Monika: So, then of course, I had to define creativity, it’s my own research, so it’s my own definition. I could do whatever I want. So, I defined creativity as the moment when you make a mistake and when you have to learn and you have to step on to doing something new, which as, a lot of artists know, is very often the moment that you get a sort of epiphany.

JA: That moment when it all goes wrong and you realise that this piece of work isn’t going to turn out as you thought unless you intervene. In weaving, which is the craft I know best, they say every piece needs at least two mistakes, one to let the god of weaving in, and another to let her out. But Monika isn’t talking about those kind of mistakes – these are, if you like, errors – she is talking about something more fundamental – something that needs a proper fix, where you have to use your brain to come up with a workaround that will solve the problem, so often that’s the moment of inspiration.

Monika: I think creativity is really what makes us human to, to always driven by curiosity or whatever, or playfulness. I like playfulness very much. I think play is very important, but to experience and to develop what is there already, hopefully into something more positive.

JA: We are a privileged generation compared to our ancestors in that we have some idea of what our brains look like from drawings and from MRI scans. This is data that most us will be familiar with, from TV shows if not from personal experience, but although each MRI scan is unique to us, it tells nothing about the person there. As the contemporary artist Susan Aldworth says: “You can look into my brain but you will never find me”. She describes: “the enigma of invisible thoughts arising from material structures”. If Monika wanted to discover more about what those brains were thinking, she felt imaging wasn’t going to help her.

Monika: And I think that’s the whole main point is that we all have brains. We as humans, we are very, very similar if you just look at the brains and the structures. But at the moment when emotions enter the whole thing, then we become individuals.

JA: And here is a paradox that has been recognised by philosophers and thinkers down the ages – if we want to reflect on our thinking it helps to work matter with our hands. The artist and inventor Leornardo de Vinci could not think without drawing at the same time. The philosopher Descartes wrote “while I write – I understand”. The activity of thinking and using our hands are closely connected to each other. So, to get people to think about their own creativity what Monika asked people to do was to stitch a brain:

Monika: So, people were sent a template with a printed midsection of a brain on it and yarns and the needle, and they were asked to stitch a brain. And they could do with those scanned materials, whatever they wanted. The, the point about setting up a good research is that you, especially something like that, where you want the cooperation of as many people as possible, is to leave it open at, but at the same time define it so it doesn’t go into a vacuum. But the next step was that if people sent me a photograph, I offered them the service that I set up a website and I put up a photograph of their stitched brain. And after that, I invited them to fill in a questionnaire with 15 easy questions, which was about how old are they? Were they brought up in a craft environment or not? And, and in the end, they could fill in personal remarks about the project.

JA: Monika was asked to present the project at a number of symposia and the idea of Stitch Your Brain simply exploded. She found herself handing out around 1000 kits.

Monika: What happened as well is that people started to send me the actual works. I only wanted the questionnaires and the photograph, but all these packages arrived in the post and <laugh>. And I realized that the idea really took hold of people and they really got triggered, which actually is what I wanted. I wanted people to use their creativity and just only to trigger them to make something. So, the whole awareness about what the brain is, has become very much common knowledge and was relatable for people. And the big thing as well is that if you ask people to stitch your brain, just imagine if I had asked them stitch your heart, that would’ve given completely different results because stitch your brain, we, we identify with our brain, our brain is what we are. And, and this ended up in everybody sort of in the end stitched a self-portrait of themselves.

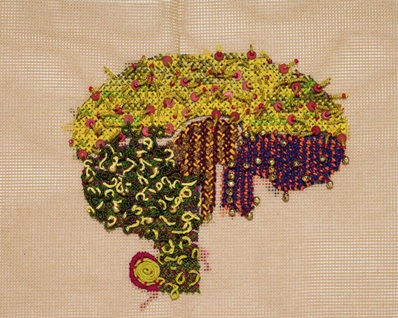

JA: Many of the brains have been gathered together into a book that was published earlier this year. As a collection of art, the brains are utterly beguiling. They are beautifully realised in many different techniques and forms. The sheer complexity of the way people expressed connections, emotions, the multitude of information that the brain holds, the balance between creativity and chaos, all of this is breath-taking. They seem to me to embody creative thought. I have posted pictures on Haptic & Hue’s website and also a link to Monika’s webpage.

Monika: Quite a lot of people took it as an invitation to share quite real, really personal, intimate thoughts, which is really interesting. I’m talking about what I call the Amsterdam Brain Collection, which has 102 stitched brains. There’s only eight people who actually tried to make a visualization of the brain. And there’s just one, just one, and she’s a neuro-scientist, who stitched something that was like an MRI scan. And the other seven who said they were actually trying to image the brain. They did it in the most artistic way. Like they stitched five birds, which represented the different areas of the brain, or they stitched flowers, or they made a tangle of threads to show the connections. So that’s the interesting thing that of all of the brains and as well all, most of the other ones that are on the website, there’s hardly anybody who relates stitch your brain to an MRI scan.

JA: One of the most important things Monika learnt from the project was how fundamental recollections and experiences are to our creativity.

Monika: I think that thing that struck me most is how important memory is. Memory is a gift, it lies dormant within us, and it just needs a trigger to come out. And very often it, it takes years and years and years until something comes out. And my own memory at the moment is about all the sculptures I make really have a connection with the photographs my father took as a steel worker, which are the same sort of constructions. So, I think, and that works for a lot of the participants as well, that they really go back to memories and, and they visualize them as well in a very material way, which I think is interesting because it shows that our memories very often are connected, for example, to sensory input: smells or sounds, but very often as well to, to textiles, especially to textiles.

JA: She believes that people begin to build up a vital understanding of touch from birth.

Monika: I just think materials are just so important in our lives, and it starts from the very beginning when, when babies start to explore first with their mouths, but then with their hands, what material is like. I think materials can be really, really inspiring. And in that way children nowadays are too much involved on screens. I think this might hamper their development of building up your own personal material library because you have a material library through your fingertips. You, explore the world through your fingertips, and all of that is stored in your brain. So, I think even sometimes looking at material can definitely trigger to make something, to touch it. I mean, just looking with your eyes at something, you can feel the sensation of, oh, this is wool, or this is metal. So this obviously is a sort of very direct connection between our sensory tips fingertips and, and our brain. And it, it can be a really strong impulse to start making then.

JA: Not everyone who took part in the project stitched healthy brains, some created their experience of depression and neurological disorder:

Monika: The main body of people who took part in, in the project were women older than 50. So very often they were as well carers. So, there are stories stitched mainly of carers who show the difference between a diseased brain and a healthy brain or as other ways to show what, what happens if a brain is not functioning, one thing is that try to visualize that in, in, in the stitched brains, and you, you read it in the comments. And the interesting thing is that these are the great life events. If you care for somebody you love and who will eventually die, I mean, this is what art is about, that you try to get hold of the, of the great life events and to put it into material and to put it into a form, a visual form, not just in words, but into threads, textiles again, means as well that if it bears you down the moment you get all the dark thoughts about the terrible things you are witnessing and, and you’re taking part in, the moment, you can, you can get them out of your head and give them a form, a material form, it’ll lighten your life. And that’s something that once a patient from psychiatry said against me. And I thought that was a marvellous way to, to say it. and he said, I can still hear the ravens circling around my head, but I can prevent them building a nest in my head.

JA: And that is an incredibly important part of what working with material, any kind of material, can do:

Monika: And I mean, that’s just what making with your hands does as well. And, and there’s the meditative aspect, and of course in, in psychiatry and in therapies, this is being used as well as, as a therapy to help people to get dark thoughts out of their head and to put them into form, which makes them in some way manageable and, and lighter.

JA: When I read the notes that went with the pictures of the brains I was struck by how many people said that they started their pieces not really know what they going to do, they let their hands lead them, and Monika says that one of the principal things that the project taught her is that there is a dialogue that goes on between our hands and our brains when we make things.

Monika: I got one of the technical art historians, and I employed her to analyse all of the brains for materials and techniques and so forth. And, and she, Mané van Veldhuizen, I have to name her. She wrote an excellent article in the book about material knowledge. And she introduced the term of affordance of materials, which is that you start working with a material, but the material will answer back and will show you what is possible. So, then you realize that in your brain and you see what with your hands, you can stretch that material too, and then the material will answer back in a way, it’s possible or not, or you can do this or that or the other. So, there’s this constant dialogue going on between your brain and your hands and the material.

JA: Here is tacit knowledge – a form of wisdom that has to be experienced through our senses and cannot be put into words. Its far easier to tell the difference between fabrics like a thick wool or a vintage silk by touch than to try to explain it in words. This is how your sense of touch informs your brain and the two start to work together. But unless we have the memory of having felt both fabrics we have no knowledge to draw on, and Monika strongly believes that tactile deprivation amongst today’s children has a strong impact on their well-being and health.

Monika: Well, my mission really is that I, I wanted to have facts to show how important it is to have good craft education. I’m just completely frustrated by the way our governments keep cutting all, all the expenses. And that started with when my two children were at primary school, all of a sudden the craft teacher was gone and they had to do these really stupid tasks., I just thought you have to prove in numbers how important it is to educate people about what they can do with their hands, because it gives them a sort of self-reliance and, and an idea about what they could, what they can do, and independence, which is just uncomparable to anything else.

JA: If you want to try your hand at Stitching Your Brain, Haptic & Hue will be giving away nine of the kits with this month’s Friends of Haptic and Hue. We will also post details of where you can buy you own kit on the webpage for this episode.

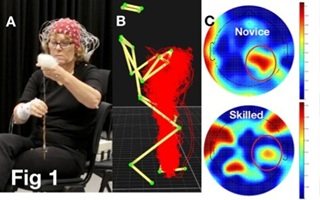

Those of us who weave, spin, knit, quilt and sew or take part in any of the wonderful myriad of textile crafts use more than just our hands, our bodies are involved as well, Sore muscles and creaky joints come with territory, but this is where brain imaging – in the form of electo-encephalography – can tell us much more about what is going on in terms of the connection between the brain the hands and the body: Here’s Mark Schram Christensen from the University of Copenhagen:

Mark: My own background is in experimental psychology and cognitive neuroscience. I’m associate professor in cognitive psychology and psychological methods. And I am really interested in looking at this intricate interaction between mental processes and how we use our bodies.

JA: He set up an experiment with the Centre for Textile Research to see if the learning processes that take place when you spin a piece of yarn, were visible.

Mark: When we compared novices and skilled spinners, what we could see was actually that the way that the brain communicates with the muscles that are doing some of the very intricate parts of spinning a yarn. So, pulling out the wool from, from a lump of wool to actually create the yarn, we could actually see that novices, they seem to have a much tighter communication between the brain and the muscles, indicating that there is some kind of learning process taking place when they, for the first time are actually doing this. Whereas our expert spinners, that didn’t seem to be the case. So, so we could actually have some early indications that there is a difference between whether you are a skilled spinner or you are a novice. And that gave us an indication, okay, maybe we can actually use that also to differentiate between the use of different tools in skilled spinner. So, we could actually start to think about the fact that you use different tools, whether that is something that you can just shift between those tools or whether it requires an additional effort in in learning to use a new tool.

JA: One of the tests he carried out was with Eva Andersson Strand, one of the founders of the Centre for Textile Research in Copenhagen, an archaeologist who specialises in textile tools. He recorded her using a drop spindle to spin two kinds of yarn, one spinning session went well and the other not so well – and on the brain scans it produced greatly different results- Here’s Eva:

Eva: Well, the first test we did was feeling very well. I was very happy to see that there was an activity <laugh> in my brain for the first to see. And I also thought it was fascinating too, when then Mark analysed the data that we got, that he could not just see that there were activities, but also when I was doing the different processes, which is in spinning when you pull out the yarn, when you turn spindle around and so on. And that is actually visible in the data. And I think that was also why I was so frustrated the second time that I, I choose the wrong material, because the wool I choose was not good to spin with a tiny, small spindle. It, I would have needed a much larger spindle to, to spin it. And I didn’t have that.

JA: So, Eva had two tests: one where she was spinning very happily and the second where everything went wrong, her frustration showed up quite clearly in her brain:

Eva: But it ended well, it was interesting also how we could see when we, you put the graph beside each other, the graph when I could see how my brain looked like when it was working and the other graph when it was not working. That was quite interesting.

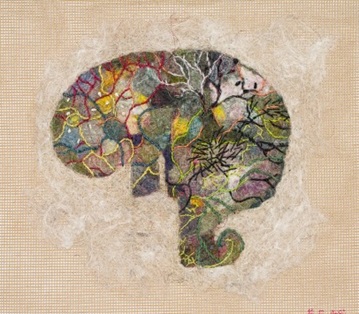

JA: Mark picked out part of her brain activity from just one electrode above her motor cortex and looked at a time frequency plot from the spinning session that didn’t go so well – you can see there are certain frequencies where Eva’s brain oscillates more – much more. As a present for her the staff of the Centre for Textile Research turned Mark’s brain plot into a wonderful tactile tapestry that hangs on Eva’s office wall: a picture of her brain struggling to spin with unfamiliar material:

Eva: Today, there is a lot of effort put into what we call craft therapy. Craft is very healthy. Many people enjoy craft. We have a flow, you can concentrate, you get relaxed and so on. But there is also the backside of it, like when it’s not working, what is happening then? How long time does it take to learn craft from when you were the beginner to the skilled one? What happens when you get older? Can you still perform the craft the same way you did when you were young? And also, this, yes, it’s nice to have a flow, but you also got this very romantic shimmer, so to say of it. But when you have to do the craft, when you really have to perform it for spinning all the yarn for sail cloth, for example, Viking sail cloth, you need to spin around, yeah, more than a hundred, maybe 150, 200,000 meters of yarn. Yes, it’s nice if you have a flow, but do you really enjoy it? How does it affect the body? Well, the, the challenge is that I have so far never worked with a craft person that don’t have problem with her body. It’s either the hand of the spinning or the shoulder of the weaving. And that is something that we can learn more about.

JA: As well as using brain imaging Eva and Mark have also used motion capture technology – the process of digitally recording human movement to create animation. Neither project has been able to continue for lack of funding – but they hold out the possibility of greater understanding for archaeologists.

Eva: I think what is really, really important here is that we produce, when we are spinning, when we are doing the spinning test, we, we have a material that we can then compare with an archaeological material. We can look at the threads that the beginner spun, for example compared with the threads that experience spinner spun. And that give us some idea that we can then look at archaeological textiles and, and start to discuss are these, are these beginners or are they, how experienced are the spinners? Because we have also in the materials uneven and evenly spun yarn. But it’s also more the bigger picture because the question you always get as an archaeologist working with craft, especially when you come to specialized craft, they say, how did I come up with this? How did I start to do it? And that is a very difficult question to, to answer. But the thing is that if you are producing something, and that is, it makes your body feel very good, well, when you are performing that of course make you do perform even more and to continue and to develop. So, I think that is also an interesting aspect of this project. And it’s also when do you stop to learn, when can you do everything?

JA: For Mark the project goes to something fundamental about being a human being on this earth. When we move, he says, we are in constant interaction with our environment.

Mark: So, the small intricate sensory perceptual experiences that we have, and for instance, we hold the yarn or we touch a piece of wood is actually feeding into the online decisions that we’re doing while we take actions. So, we are not just creatures that think of, of a detailed plan. And then we execute it. All those small intricate sensory experiences that we have and, and sensory inputs that we get from all of our senses, from the vision, from, from our bodies. They actually influence the way that we make our movements and how we decide to do one movement compared to another movement. And it’s not like a, a necessarily a, a conscious decision that we make. It’s taking place extremely fast. And that I am really intrigued about with, with these types of experiments that we can actually look at both how the body acts and we can then analyse the material that we’re looking at afterwards. So, my dream about this project is that we can really start to understand this close loop between us as humans acting in a world that provides us with some sensory information. And we cannot really separate ourselves from acting with the, with the external world. It’s something where we are in constant interaction.

JA: The example he gives is working with wood:

Mark: Let’s say you, you were involved in, in in carpentry or something like that. Then, then there is a small knot in, in the wood. You would have to sort of negotiate that and, and move around it in, in certain ways. And that ends up being then how we have actually acted on, on this piece of the material. And that closed complex circuitry of interactions between us as human bodies and the external world, and then the processes that take place in the brain, why we do that is, is really where I could see that, that using these crafts processes where we have this immediate feedback from the world is, is really important to understand, because we as humans have evolved with our bodies with certain capabilities. And that has probably also been decisive factors in, in how we form our lives in, in this closed interaction with the environment. So, so my ideal avenue in, in this field is that we can actually investigate this, and we need these very closed interactions where we immediately feel something from the external world that influences the decisions that we take.

JA: Stitch Your Brain and Mark and Eva’s project measuring how the body and brain work in harmony are very different projects – one sets out to measure creativity and the other skill and how we execute that skill, but both tell us an enormous amount about who we are and why textile crafts matter, not just in the past but as a modern living practice and part of an interesting and fulfilling life. And if you are contemplating a project and don’t quite know where to start here is a final word from Monica Auch of Stitch Your Brain.

Monika: I did another little survey and I just asked a few people what they thought about the project now in hindsight, there’s a few people who said they’re just so happy that they did this because they did realize how important it is to, to work with your hands, and that you shouldn’t be afraid that you will fail or whatever, because you, you just have to go on and you find a solution and, and you just, you just get into a dialogue with the material and you do stuff. So, I think that that showed me that you have to trigger people. You have to find a good task or just a good impulse and, and give them the most ordinary materials in order to get them going.

JA: Thank you for listening, and thank you to Eva, Mark and Monica for their insight and input to this episode. If you would like to see pictures of Stitch your Brain or Eva’s Brain woven in tapestry then head over to www.hapticandhue.com/listen and look for Series Seven. Haptic and Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews. It is edited and produced by Bill Taylor and sound edited by Charles Lomas of Darkroom Productions. It is an independent podcast free of ads and sponsorship, supported entirely by its listeners, who generously fund us through Buy Me a Coffee or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. Friends get access to free textile gifts every month and an extra podcast hosted by me and Bill Taylor, where we cover interesting events and the textile news of the day. To join Friends, go to www.hapticandhue.com/join We will also be back next month, but until then its good bye from me and enjoy whatever you are making.