Returning The Spirit Of A Soldier: Japan’s Yosegaki Hinomaru Flags

Episode #34

Yosegaki Hinomaru were good luck flags signed by the friends and families of Japanese soldiers going off to war. Soldiers carried them close to their hearts to remind them of their homes and families. Many became war trophies for Allied soldiers, who were under orders to search dead Japanese combatants. But now, after all these years, some of the families of veterans are seeking to return the flags to the Japanese families of the men who died on the battlefield. This is a difficult and often heart-rending moment, both for the family giving up the flag and for the Japanese family receiving back a small piece of cloth that represents the return of their relative’s spirit home after more than three-quarters of a century.

This episode deals with war and loss, death and mourning.

The people you hear in this episode are:

Keiko and Rex Ziak – who founded and run the Obon Society – which you can find at https://obonsociety.org/eng/ where you will also find a number of videos and pictures about their extraordinary work. If you would like to make a donation to help them continue their work you can do this at: https://obonsociety.org/eng/page/support

Terry Stockdale, who you can see in the pictures below.

You can follow Haptic & Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic & Hue name.

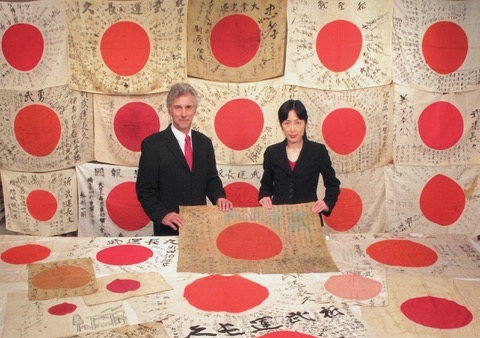

Rex and Keiko Ziak surrounded by Yosegaki Hinomaru Flags

A young man sets off for war with his flag surrounded by his family.

Soldier and flag from his friends

British soldiers displaying a trophy flag

Hazel’s Yosegaki Hinomaru flag – just received – will it find its family?

US Soldiers with a Yosegaki Hinomaru

Terry Stockdale in Osaka, Japan

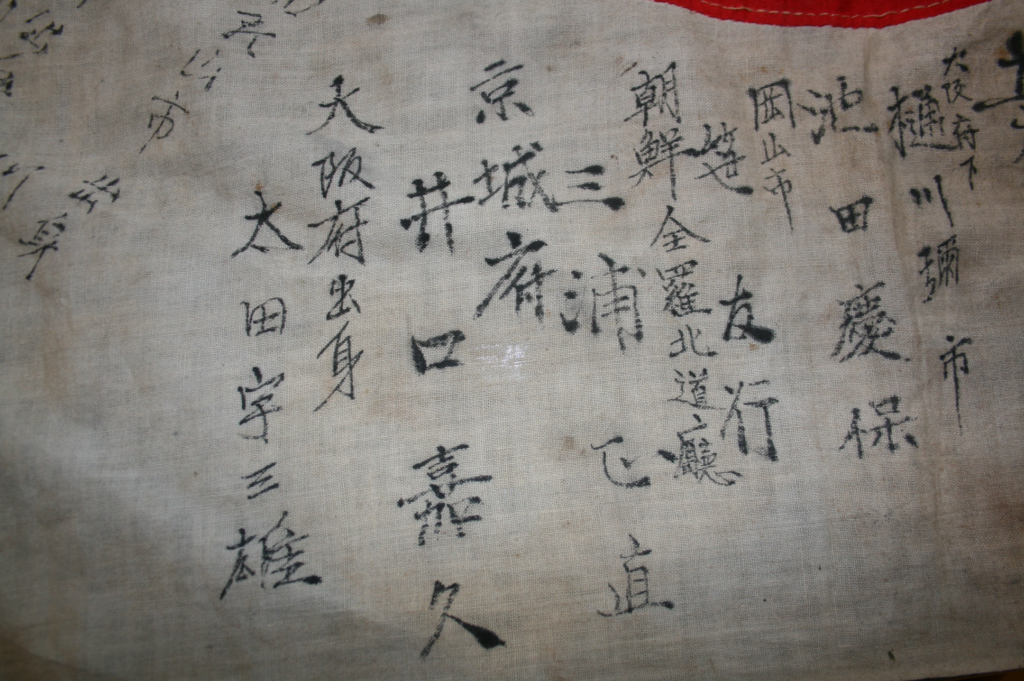

The Yosegaki Hinomaru flag Terry returned to the Kishi family

Masaru Kishi and Terry Stockdale toasting the return of the flag in Japan.

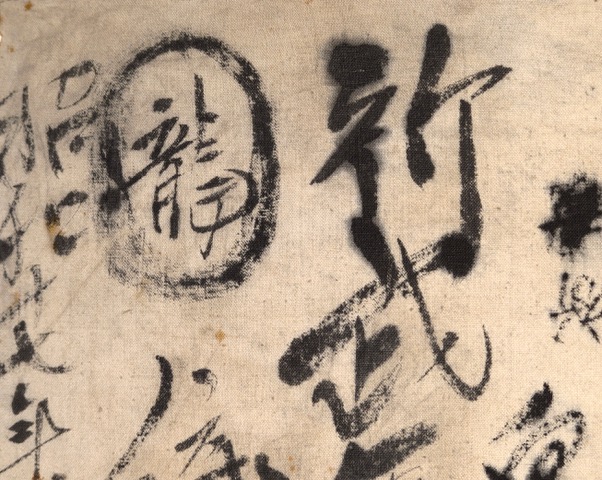

Close-up of writing on a Hinomaru flag

Close-up of writing on a Hinomaru flag

Terry Stockdale’s other Hinomaru flag, which has yet to find its family.

Returning the Spirit of A Soldier – Japan’s Yosgaki Hinomaru Flags

Textiles carry our emotions in an especially powerful way, and in a form that transcends borders and nations, language and culture. They can unite us across divides and heal bitter divisions. When we make something, it can be an expression of our love for someone, or a way to bring comfort. Fabrics can send messages about how we feel and wish to be seen – think of the glorious Renaissance paintings of princes and princesses projecting their authority or telling us how devout they were, or textiles can act – like an old cardigan – as a potent reminder of family members who are no longer with us.

Haptic & Hue’s second series was all about how feelings are bound up with textiles. But in all those stories I never came across one in which a cloth became specifically imbued with the spirit and the soul of someone.

This episode is about Yosegaki Hinomaru flags, personal flags carried by Japanese soldiers in the Second World War, but which over the course of 75 years have become something much more powerful – the last embodiment of a long lost relative:

Keiko Ziak explains what the words Yosegaki Hinomaru mean:

Keiko: Yosegaki Hinomaru has consistence of two words. Hinomaru part is national flag, just like American called their flag Star and Stripes, or British called Union Jack. We as a Japanese call Hinomaru as a Japanese flag. And the other word, Yosegaki, means: together to write. So the summary of Yosegaki Hinomaru means together to write on the Japanese national flag.

Keiko – who is Japanese, founded the Obon Society with her husband Rex, who is American. Their mission is to bridge the gap between the families of Japanese soldiers and Allied and American veterans and return Second World War battlefield textile trophies to Japan.

These flags are now more than three-quarters of a century old and in that time their meaning has changed dramatically. They began life as good luck symbols created by the friends and family of Japanese soldiers sent to war. They later became trophies for Allied soldiers, many of whom endured great hardship, and finally, in rare cases where they have been returned, they have been transformed again to become a way for Japanese families to welcome home ancestors they thought lost forever.

This episode comes as nations across Europe and in Canada gather for Remembrance Day, where we mark those that we have lost in conflicts. It is always a time of reflection and melancholy as the light fades and winter creeps in. And just to warn you, every one of the people I spoke to for this episode wept – me included, and there is no shame in that. We talked of war and death and profound feelings of loss, and if that isn’t your thing then listen no further, but I also found something miraculous and healing in this too, something delivered by very humble pieces of cloth.

Welcome to Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles, my name is Jo Andrews, and I’m a handweaver interested in what textiles tell us about the story of humanity and in particular, the meaning we attach to cloth and fabric.

Keiko explains how these flags were made and given to Japanese soldiers in World War Two.

Keiko: Before he was sent off to any of the battlefield, family who purchased or handmade small Japanese national flag, because they have surrounding the white margin of the part, they write their signatures or personal message encouraging for this soldier to a battlefield. So mother, wife children, if they married or friend, neighbour, relative, classmate, and if he works, maybe a company colleagues, or if he play kind club or soccer, football, any sports team, teammate. So anybody who knows this person who cares, they write personal message and signatures, and then give it to him.

Jo: And when the soldiers went away, were they just carrying one of these flags, or might they be carrying more.

Keiko: At least one easily, but if belong to one with a family or relative and friends, neighbours, one could be from companies, colleagues, or if he’s a student he was given by the school teacher and craftsman, that’s another type of the flag. So we would say sometimes one flag, sometimes two or three, bring the multiple flag with him.

Jo: And how would the soldier have carried the flag? Where would he have had it?

Keiko: Since the Japanese flag, it’s very easy to fold it, to make it small. And then most of the soldiers, they keep it very close to his heart and then he carry it with him very close.

Jo: So he would carry it inside his shirt or inside a pocket or something like that?

Keiko: Yes. Yes.

Jo: And did every soldier have one? How common were they?

Keiko: Well record shows during the World War II, about 8 million Japanese soldiers are drafted so easy estimate, at least one, sometimes two or three flags are carried by those Japanese soldiers. We would estimate at least easily over 10 million flags easily created it during that time.

Jo: And how would the soldier have seen this flag? Would it have been a very nice reminder of people at home or would it have carried some kind of protective thoughts with it? Would you have seen it as a protection for him in battle?

Keiko: Above all I would say this is reminder of the loved one who care for him back home. Imagine a soldier far away from home, he’s alone with a war, body, other soldiers, but all away from loved one. That flag written by each one of the loved one remind of him at home, who he defends for, why he’s there. So that’s to encourage him and also just comfort him. I would imagine. So that has everything spiritually. You are not with them physically, but spiritually, all the loved one, what he wanted to protect, they are with him close.

JA Script: Keiko’s family comes from Kyoto. Her grandfather was one of those soldiers who went off to fight in the War, and like hundreds of thousands of other Japanese soldiers, he never came home.

Keiko: My grandfather, he was no different than any other Japanese soldiers. He was just an ordinary farmer in the countryside. He had the two small children at the time, and then he was drafted and then sent off to Burma and then he just disappeared without the trace. So, no remains, nothing came back and the family didn’t know what happened to him at all. Except Japanese government sent a death notice to my grandmother. So, my grandfather we know he was killed in action in Burma, but nobody knows exactly what happened to him, how he died and how he died or where exactly he died.

Within Japanese culture, there is a great respect for a family’s ancestors and it is important to visit and to maintain their graves. But the deaths of these soldiers in unknown places made that impossible.

Keiko: My childhood memory, each summer season we call Obon season, that as Japanese, we believe ancestors come back on earth to visit each family. So we clean the grave and then we visited to a cemetery, each grave and pray for the ancestor, pay the respect and thinking of them. So that’s a very much Japanese custom. Each every summer season in August, we always go to grandparents’ cemetery and then visit including grandfather’s grave. And each, every time when we visited to pray for the ancestor, my mother said always, she said, grandfather died in Burma and nothing came back to the family except it was sent a small rock with a death notice. So, the priest and the family devastated, nothing to bury in the grandfather’s grave. So, since nothing to bury, priest decided to bury a small rock in his grave. So, my mother, I, I clearly, it, it just sunk to my brain. Oh, so Japanese custom is we cremate the bone. So that’s very important for the Japanese custom, but there’s no bone. There’s nothing. So, so my mother said, there’s nothing but just a small rock is in that grandfather’s grave.

Keiko says this wasn’t talked about in Japanese society and it was a long time before she realised that many other families went through exactly the same thing. They too lost fathers and brothers, uncles and sons, and instead of remains, they received a rock, or a piece of wood, or sometimes a small bit of coral. Rex Ziak, Keiko’s husband, was amazed by this story the first time he heard it:

Rex: I was just stunned to hear this story of her grandfather having been drafted and sent to Burma and disappeared without a trace, just gone, nothing. In fact, she told me that the story she was told that her mother had heard from her mother. So, the grandmother, she received a letter in the mail from the government some while after the husband had left. And along with this letter, which was announcing his death, there was a box, the small box. And I interpreted it to be like the size of maybe that a wedding ring would come in a little small, little, like maybe one-inch or two-inch square box. And inside of the box was a stone, just a little pebble. And, and I realized that this was the Japanese government’s way of informing a family that not only the person had died, but that there would be no remains coming back, rather than write in the letter that he is missing in action, or there’s no trace of his body found. Or you can just forget about expecting any bones to bury. They would send a rock to the family and from that, they could figure out if you got a rock, that means there’s, there’s nothing coming home.

JA: And for more than 60 years that was that. In Japan hundreds of thousands of soldiers went missing or were taken prisoner at the end of the war, and as Rex explains many mothers went on hoping year after year that their sons might come home.

Rex: In the years after the war the women of Japan would get news that a ship was coming in and they would all go down to the dock and wait to see this ship come in. And they would see the people get off the ship. And they were looking for their missing sons because some had been held captive up in Russia. Some were down in the south Pacific islands, holding out, some were being held prisoner here or there, wherever. And so, the soldiers didn’t come home quite like our soldiers came home, but they trickled in over the course of years and years. In fact, in 1955, Russia is still releasing back to Japan, captive soldiers. They’ve held for 10 years, mm-hmm <affirmative> alive. So these mothers would go down along the dock and watch every ship and stand there, as the people come off the gangplank waiting for their sons.

JA script: But in 2007 something dramatic happened in Keiko’s family which started with a phone call to her uncle:

Keiko: Well, it was a year, 2007 in summer, after 62 years from the end of the World War II in the middle of the nowhere, we have no idea how, but somehow my uncle received a telephone call and this telephone call was saying, do you know such this name? And that my uncle have never heard his father’s name for many number of years. And then my uncle said, well, that’s my father’s name. How do you know? Then that person said, well, I have something here. And then he like to have received will be happy to send it to you. So here they are in the middle of nowhere, my grandfather’s flag, Yosegaki Hinomaru, was returned to my uncle. He happened to be the same house where the grandfather resided in the countryside, he suddenly received it. And then that was a surprise to entire whole family, my uncle, my mother, entire whole family.

JA Script Rex says it took time to unravel the story of how this flag has actually been returned and it casts a great deal of credit on a very determined set of hotel staff who had Keiko’s grandfather’s Hinomaru flag left with them by the son of a Canadian veteran.

Rex: This Canadian man, who on a business trip to Asia had arrived in a Tokyo airport for a layover for several hours, jumped in a taxi, went to a hotel and handed the hotel staff a flag that, and then said, find this family. My, my father had this and he wants it to go back to the family. And then he left and this hotel staff spent, I don’t know, six or eight months putting notices in newspapers and whatever. And somehow through diligence and kind of this unusual name, they were able to trace this object, this flag, she talked about back to her uncle.

JA script For Keiko and her family though this was more, much more, than the return of a piece of cloth, it was as though their grandfather had finally found his way home:

Keiko: It’s not the flag. My mother said finally, grandfather came back home. His strong spirit really wanted to come back to see a family of family. So she said, finally he came home. So I wouldn’t say it was not a flag. It was a grandfather spirit, grandfather, himself, my mother and uncle. They do not have any memory of their own father, but something still exists in this world after 62 years took time that grandfather finally came home. So I would say that that was not the flag.

JA script: Keiko’s uncle keeps his father’s flag at home – his father name is clearly legible and it contains the signatures of many local friends, some of whom did come home from the war and one of whom Keiko remembers. The family still don’t know any more about how their father and grandfather died or where. But they do know that his flag ended up in the possession of a Canadian soldier and this soldier’s dying wish was that it should be returned to Japan.

Keiko: So all the miracle of the dots connecting, and finally came to, to my family. So we don’t know anything about what the truth, but what we knew, or my mother said it was a miracle. So absolutely a miracle. The strong spirit of the grandfather made this miracle, somehow the flag survived. And then I still remember, first time I saw the flag, I expected something maybe blood or a torn apart, or in the middle of the jungle or the wet. So that, that flag was very bad condition and dirty, or who knows. What I would expect is something really bad condition. And exactly opposite with my huge surprise, when I first time see grandfather’s flag was so pristine, white writing was clear and folded. It was so pristine. And I could not imagine how can they survive such a clean condition? It’s almost that they didn’t go through the battlefield. <Laugh> how does it happen? You know, so, so the conclusion of my family, my mother saying this only we can put our head around is a miracle.. So that was, that was our family story. Nobody can know how flag travel all the way through, around the world, coming back home after 62 years with a good condition.

JA: But for Rex, Keiko’s story had a different resonance. He is the son of a US veteran who fought in the Pacific and as he heard Keiko describe this ‘miracle’ – he wondered if there were other flags like this as well:

Rex: And so she’s telling me all this, and in my mind, wheels are turning and I have absolutely no idea what she’s talking about. And so later when I come home and I remember that story and I go to the computer and I start to poke around a little bit, I see one of those objects such as this Japanese flag with black letters written on a Japanese flag. And I see another one and I see another one. And I go into Google images of World War II and Japanese flags. And here are literally hundreds of pictures of American soldiers and British and Australians holding these up on battlefields. They’re holding up these flags and smiling, and this whole story unfolds in my mind. And I’m kind of like falling down this rabbit hole of this. I can remember writing to Keiko saying that flag that came back to your mother, that was not the only one like it in the world, there are many of them. And her responding to me, like, what are you talking about? And so gradually we fall into this, this world of, there were thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions of these flags during World War II, and they were taken and they are being held by veterans or the families of veterans.

JA: And that gave Rex an idea

Rex: Then when I saw the impact that the return of this single object had on Keiko’s family. I said to Keiko, maybe we should try to make a miracle for another Japanese family. Maybe we should see if we can find some of these or people will give them to us. And if we can trace them back to a, a, a, a son or a daughter in Japan and she readily agreed, okay, let’s do this. And that’s how we, we began.

Together they set up the Obon Society and its mission is to receive these good luck flags and other war memorabilia acquired by allied soldiers fighting in the Pacific and with permission to return them, if they can, to the Japanese families of the missing soldiers. It is meticulous and difficult work. So far, the Obon Society has received over 2,200 flags from Allied veterans and their families, and, incredibly, they have managed to return nearly 500 of them: Some of the stories are heart-rending:

Rex: We have on several occasions helped people, facilitated, made the arrangements for them to take the objects back to Japan and to have that face to face meeting. One in fact was a World War II Marine veteran from Montana in the state of Montana, who had recovered this on the battlefield and could remember it so vividly that he could tell you how the soldier was dressed. He could even go right down to describing how he was laying on the ground when he was discovered and how he rolled him over, whether it was the left side or right side. I can’t remember how he rolled him over and looked and realized that it wasn’t shrapnel or bullets that had killed the Japanese, but it was like a shock concussion of an explosion and how he had taken this flag and brought it home. And he sent it to his daughter, sent it to us to find a family. And when we found the family, it was a shock, we found a brother and three sisters, two or three sisters still alive, because they thought their brother had died in a, in a sunken ship, by a submarine. And so the fact that he had died in a battlefield in Saipan, and here was this American who not only knew where and how he had died, but was the last person to probably ever see him. It became this dynamic moment of, of these brothers and sisters who always wondered what happened to their eldest brother and this Marine who knew. And so, we made arrangements and we asked the, the Japanese, would you ever want to talk with the Marine? Oh, they would very much welcome him there to their town to hear him. And we asked the Marine, would you ever consider taking this back? Oh, he’d be honoured to take this back. And so, we made that historic event occur. and I’ll tell you something. That’s so fascinating for me that when that young brother is handed that flag by that Marine in this ceremony in uniform, he holds it up to his face. The young brother, now a man in his eighties, holds it up to his face and it looks like he’s crying into it. It looks like he’s he’s weeping, but he doesn’t. And, and, and we didn’t understand. And then later on, he explained to us that the last time he saw his brother, they sat under a tree eating this, these little rice balls that they prepare called ongeti. And he was there with his sister and his elder brother eating this ongeti and the wind was blowing. And he could smell some oil that his brother had combed into his hair. And that fragrance of that hair came to him. He was like 14 years of age at the time. And he could smell his brother’s hair oil. And he remembered that smell for those 80 years. And so when he picked up that flag, that textile, his first thought was to see if he could smell his brother.

Jo: Everyone must have been in tears. I mean, the Marine himself must have been in tears.

Rex: He’s a Marine and he is very stoic, but yes, he, he was, it was very, very emotional too for, for everyone. It was, yeah, it was a very, very emotional moment.

JA: Rex says the custom of taking battlefield souvenirs is as old as war itself. And in the Pacific, Allied soldiers were under orders to search enemy combatants:

Rex: So there was instructions of everybody on the battlefield to search every deceased Japanese and go through their pockets, looking for something of importance for the war. And then where that intersects the idea of the young man from Kansas or Michigan or Florida, who has never seen a Japanese person in his life. And here are these objects that he’s carrying in his pocket that are so exotic, whether it’s a fountain pen or a letter or whatever, with this odd writing that they want to bring home to their family. And so the whole intersection of battlefield souvenirs and the taking of things, and all this is, is this world that I had never, ever thought of. But, it has consumed me for these last 13 years.

Terry Stockdale is a man who knows all about battlefield souvenirs. His father was a veteran and one night when Terry was about 5 or 6, he showed his children the contents of his US army locker:

Terry: What I remember the first time ever is he took us down one night as a family with my brothers and sisters. And he opened his, he kept all his war memorabilia in a foot locker, which all soldiers did. It was a green government issue type thing. But anyway, he went through the Foot Locker. I remember at the time he had quite a bit of stuff in there, photos, letters from his mother from home, and from his father.

JA: He also had three Yosegaki Hinomaru:

Terry: He knew they weren’t battle flags, you know, and all that. He knew they were personal messages from home. The soldiers knew that. He called them good luck flags. So anyway, I was just intrigued by these flags because they’re, I mean, they’re works of art. If you’ve ever, you’ll need to see, look at one someday up close, because you’ll see how really, how pretty they are. I don’t know what intrigued me with these flags, but the, the Japanese flags is simple and beautiful in itself. I think just a white background with a rising sun on it, just by itself. I think it’s a nice flag. But the flags my father had interesting thing on them. One of ’em had blood on it. So, and as a kid that attracts you. You know, what’s the story behind that for sure? But the more interesting thing on there was just the scripts, the, the Japanese writing just beautiful. Like I know that’s maybe what intrigued me on ’em more than anything. And knowing that it was personal names on there. So that’s kind of my earliest memories of the flag.

JA: Terry’s father had been in the US Infantry for three years. His story wasn’t an unusual one in America at that time:

Terry: It was during the depression, he, he’d just graduated high school, nothing to do. So he joined the National Guard. Montana is just a local military thing. And he shipped off to Fort Lewis, Washington. And when he was in basic training when Pearl Harbor happened. Wow. So that started the whole thing. So, he was shipped off pretty much immediately after they trained, they were trained in Australia, then they went straight to New Guinea and fought in New Guinea in around ’42, somewhere in there. And fought all the way up to the Philippines till ’45. So he spent a lot of time fighting. So he saw the worst.

JA: When Terry’s father died in 2001, Terry took two of the Hinomaru flags, with the intention of seeing if he could return them. He sent photos to the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles, he took them to the local sushi restaurant and to the Japanese Department at the University of Las Vegas, where he lives. They were polite but had absolutely no interest. And then in 2015, Terry told a Japanese colleague at work about the flags by chance. This timemthere was immediate interest, his colleague translated the names and messages on the flags, and with his colleague’s help and support, Terry did some local media interviews, found the Obon Society, and sent Rex and Keiko his flag.

Terry: I mailed it late August 15. And about the end of September 15, Obon had found a family already. It was, that was like boom, like that. And then also, oh, well, in my interview when I was doing this online interview here in Vegas, I said, Oh, it’d be nice if, if they found a family, I would, I would deliver the flag to the family, You know, just how you say things in an interview, <laugh> and not ever imagining. So then, but that was when Obon saw that in the interview, they asked me if I wanted to go to Japan, deliver the flag, and I then I, so I said yes. From that point on that whole episode, my head’s spinning, you know, it’s just, it’s more like a fairy tale dream come true. Really? They found the family and I’m, I, I couldn’t say no, you know? So yeah, I was, you know, yes, I had, I packed my bags and made sure my passport was good and went over there. I had to, had to do it, I guess since I said I was going to do it.

JA: It was an emotional trip for everyone involved. He travelled to a town south of Osaka to return the flag at a local ceremony to the Kishi family.

Terry: But their first reaction to me is, was at the train station when, when we were go going down to where they’d showed up. And then that’s where they both came up to me crying and bowing and made me cry. Just thank me, thank me. Arigato, Arigato, you know, Thank you, thank you, thank you. I, I didn’t know my father. I had my interpreter talking there, which was wonderful. You know, I’ve never, I can’t, I have no memories of my father, you know, this is, you know, so yeah. Just completely the flag to them was their father.

Jo: And, and it was, you were returning their father to them.

Terry: Exactly. Yeah. Thank you for bringing Father Home. Wow. Yeah. It’s,

Jo: That must have hit you pretty hard.

Terry: If you’ve seen videos of me along the line, that’s what, you know, I’m constantly crying. I’m, I’m in tears right now thinking about it. So yeah, it was, but to them it’s their father, you know, that’s it you know.

JA: Terry is in no doubt that he did the right thing even though other members of his family didn’t agree:

Terry:Certain objects affect certain people and it’s just hard to explain. Best thing is it is better to give than receive, even though I did get resistance from my family. My father really didn’t want me to do it. We had discussed it. So that’s not easy to do either, but it’s still the right thing to do. I would do the same thing again. You wish, of course that everybody’d say, ‘Hey, yay. Great’. You know there’s two sides to every story too. So you wish everybody’d say, ‘Yeah, wonderful’, but no, I’d do it again. I would do it again. Plus I was treated like a king when I was over there. Anyway, <laugh>. I, I really was.

JA: Rex Ziak has helped to return hundreds of these flags to Japanese families and understands better than most the changing role the textile at the centre in this story has played over time:

Rex: When it gets down to the flag and I’ve thought about this a lot, as far as a textile goes, this unique fabric has had three different lifetimes to this with three different purposes, bringing joy to three different groups. And when it was created by the mother or the wife or the family or the community, and given to that young man who was being sent off to fight for his country. And you can just imagine that that young man, and it’s jungle, it’s night or cold or hot or whatever, and he’s alone, he’s dug into a foxhole or he is marching or whatever he is with all these other strangers. But here in his pocket, he’s carrying the, the wishes and the signatures of everybody in his world. And everybody in his life who cares about him, loves him. He’s carrying that with him. And that must have given him just this tremendous amount of joy and comfort and those lonely nights, then you have this American or Australian or British or Canadian soldier on the battlefield, finding this, digging through these pockets, finding this and holding up this, what they would call flag here is this treasure, this souvenir like none other that they can take home. And it’s first of all, a flag. So, everybody’s gonna know what it is. And second of all, unlike a rifle or a helmet, it will be easy to transport because you can stuff it inside of a sock and, and nobody’s gonna steal it and you can get it back home. And then here you are in Kansas or in, in, in Melbourne or wherever, and you hold up this textile with this Japanese.in the middle of it and all this writing and what pride and joy and happiness, it must have brought that soldier and all of his family and neighbours who would’ve seen this object. And so, this item, this textile is bringing joy to a whole other community and group. There, there, it sits now in a drawer, on a frame on the wall or in a trunk somewhere or up in the attic or in the garage for 50 years, 60 years, 70 years. And now it goes back to Japan and who it’s going to, of course, are the baby brothers and sisters, or the infant sons and daughters of that soldier. Now they’re in their eighties and nineties. They were two years old, three years old, four years old, six years old, 10 years old during the war. And they’re the ones who we now find and returned these items to. And for them, here is this person who they had heard about that was their brother or their father, who was just this sort of in, like, in my case of my wife, just this unspoken hole in the family. And here they come back.

Rex and Keiko know that in lofts and basements, in lockers, and hidden away in the cupboards of British, American, Canadian, New Zealand, and Australian ex-servicemen and their families are probably thousands of other Hinomaru flags. Only last week they unexpectedly received the tattered remains of a flag from Hazel in Britain, who says her father David, or one of his troop, undoubtedly took it from a Japanese soldier when they were fighting in the jungle. She says: “this information comes with a little prayer that I and my family sincerely hope it might help you repatriate this precious flag to another family still waiting. I have no illusion how my father came by this flag but I do hope that just maybe somehow we can put a tiny piece of the horror of war to rest. Please if at all possible, let me know if you have success, as it would enable me, to finally gently close an open door on the past. Rex knows though that others may not feel the same way.

Rex:Well, I what would I say to somebody who has one of these objects? First of all, some of these families holding these items, this is a very precious memento of their father or grandfather’s service and his experience and the stories he told makes them feel like they should keep that in his memory and in the memory of that, that, that his service and for those people who feel that way, that, that item from that Japanese person is important for their own feeling of comfort and their heart. I think they absolutely should keep that because we do not want to disrupt that harmony within that family and that feeling of how they regard their father or grandfather or uncle now, for the other people who can separate out their uncle or grandfather’s service from this object and for the people who actually can extend their compassion towards the feeling of another family, like my wife’s mother, who never knew her father, and would like to bring that joy, that, that feeling of comfort, just to another human of connecting them with a loss and missing family member for those people, they can, we welcome them to mail those objects to us, and we will do our very best to find that family and get it back to them.

For Keiko this is about family:

Keiko: So, it is bottom line is this is not about Japanese. This is not about American. This is not about British. This is all about family. And this is about humanity. Everybody has a family. So, when you have missing action, somebody disappear without a trace. Family has a hole in the heart and everybody you, you can imagine. So, I don’t really think what we return it is we are doing Japanese, or we are doing this beyond of Japan and America. I would say, this is absolutely. Everybody has a family. We care for the family, I think, is that somewhere, exactly opposite to war. After the war ended, I wanted to achieve this peaceful world around the world through returning the flag.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Haptic and Hue. Thanks to Terry Stockdale and Rex and Keiko Ziak for speaking so deeply and feelingly about their experiences. Rex and Keiko’s work is entirely funded by donations – if you would like to know more about it – or see some pictures of them, and the flags described in this episode, you can find it all on Haptic and Hue’s website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen.

I need also to thank Penny Hummel – a listener who first spotted this story and alerted me to the existence of these extraordinary spirit flags. Thank you, Penny.

Haptic and Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews and produced and edited by Bill Taylor.

It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee. If you’d like to contribute you will find the button on our website at www.hapticandhue.com.

We will be back on the first Thursday of next month with something slightly different for the end of the year, an interview with the author of our choice for Haptic and Hue’s book of the year for 2022. Think embroidery, Renaissance, France, and a tragic life. It’s a great book! Join us then.

Meanwhile, it seems appropriate to leave you with 2 verses from Laurence Binyon’s, Ode to Remembrance.

They went with songs to the battle, they were young,

Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow.

They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted,

They fell with their faces to the foe.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.