Shoddy

The Once & Future King

Episode #24

Shoddy cloth and its sister mungo were first produced in Batley in West Yorkshire, a town that became so filthy from the trade they said the birds flew backward to stop the soot from getting in their eyes. Shoddy production made this part of West Yorkshire’s fortune in the 19th and 20th centuries and at one stage there were said to be more Rolls Royces in the town than in London. But it also brought a myriad of difficulties with it – from accusations of moral hazard to charges of war profiteering and smuggling. This episode looks at shoddy’s past – its role in the American Civil War and how it changed laws and divided opinion. It also looks at how shoddy, as the ultimate recycled material, is now being recast as the perfect way to cut pollution from textile waste.

This episode runs for 43 minutes.

Hanna Rose Shell is a historian of technology, a filmmaker, and Associate Professor of Critical and Curatorial Studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She has spent much of the last 15 years studying secondhand clothes, and recycled textile materials such as shoddy.

Her book: Shoddy: From Devil’s Dust to the Renaissance of Rags is interesting reading. It is in the Haptic and Hue Bookshop. UK listeners can find it here. US listeners can find it here. All purchases through the Bookshop support the podcast at no extra cost to you. Here also is her most recent article about shoddy for the Harvard Review. Here are the details of her film about Shoddy, called Secondhand Pepé Her website can be found at http://hannaroseshell.org/ And she is on instagram @hannaroseshell

Dr John Parkinson’s company is called IINOUIIO (It Is Not Over Until It Is Over). It has a website with a shop to buy recycled yarn, fibre for spinning and knitting patterns. He is also on Instagram @iinouiiorecycledtextiles If you have any idea on where he can find a home for his business – contact him!

Samuel Jubb’s book, The History of The Shoddy Trade is still in print and if anyone is interested you can find in the Haptic and Hue Bookshop: Here for the UK, and Here for the US.

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

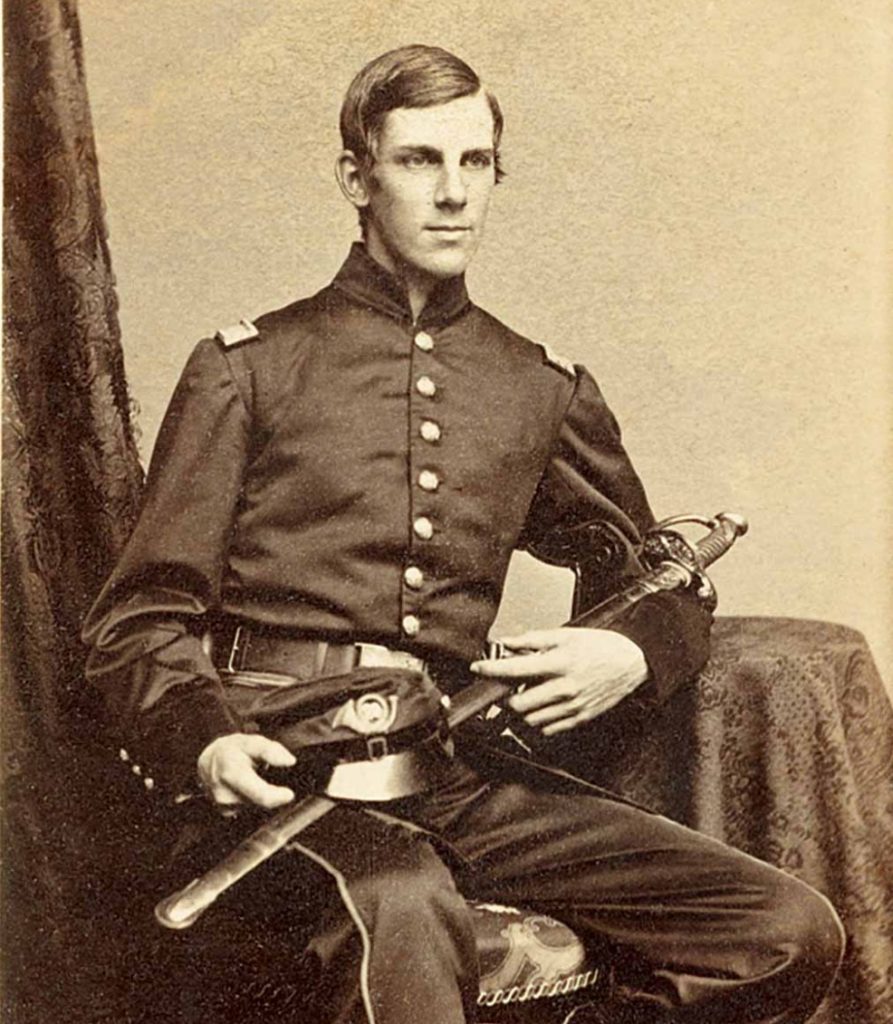

Oliver Wendell Holmes in Uniform (Courtesy Boston Public Library)

Blended Shoddy Fibre

Carded Shoddy Fibre Ready for Spinning

Hanna Rose Shell

Picture by Allegra Boverman

John Parkinson, IINOUIIO

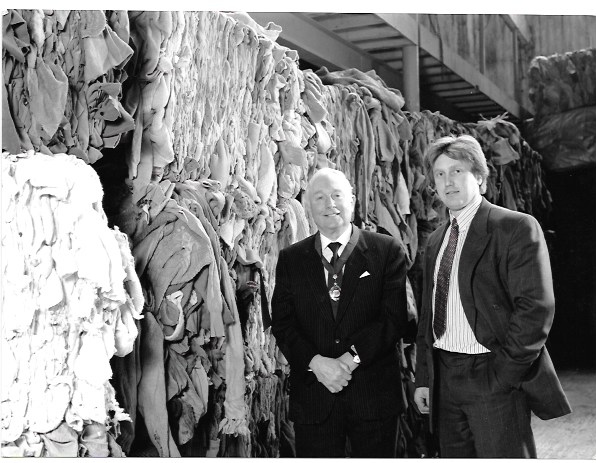

John and his Dad, Colin when they ran the first Shoddy Mill

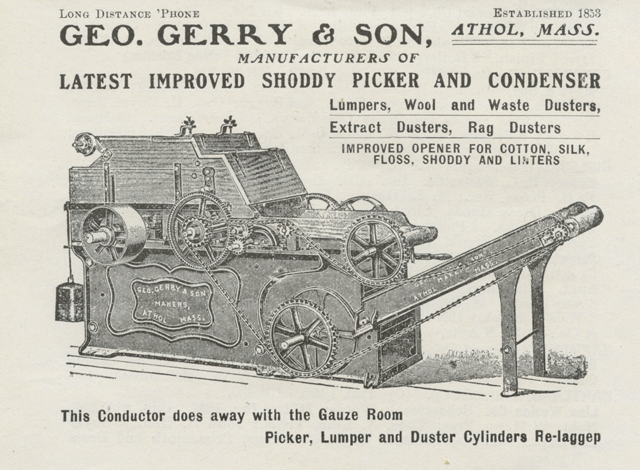

An Early American Shoddy Machine

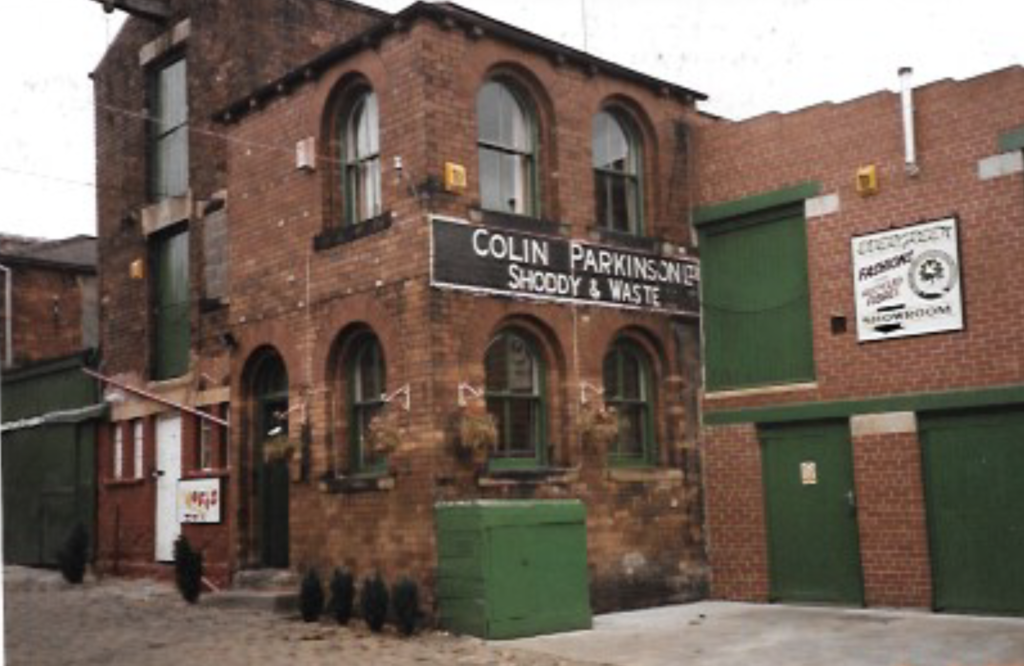

The Parkinson’s Original Shoddy Mill

Devil’s Dust – Still There – West Yorkshire, Picture: Hanna Rose Shell.

Touching The Devil, Picture Hanna Rose Shell

Dust Inside Old Mill picture Hanna Rose Shell

Devil’s Dust – Still There – West Yorkshire, Picture: Hanna Rose Shell.

Raw Material Limited Only By Our Imagination

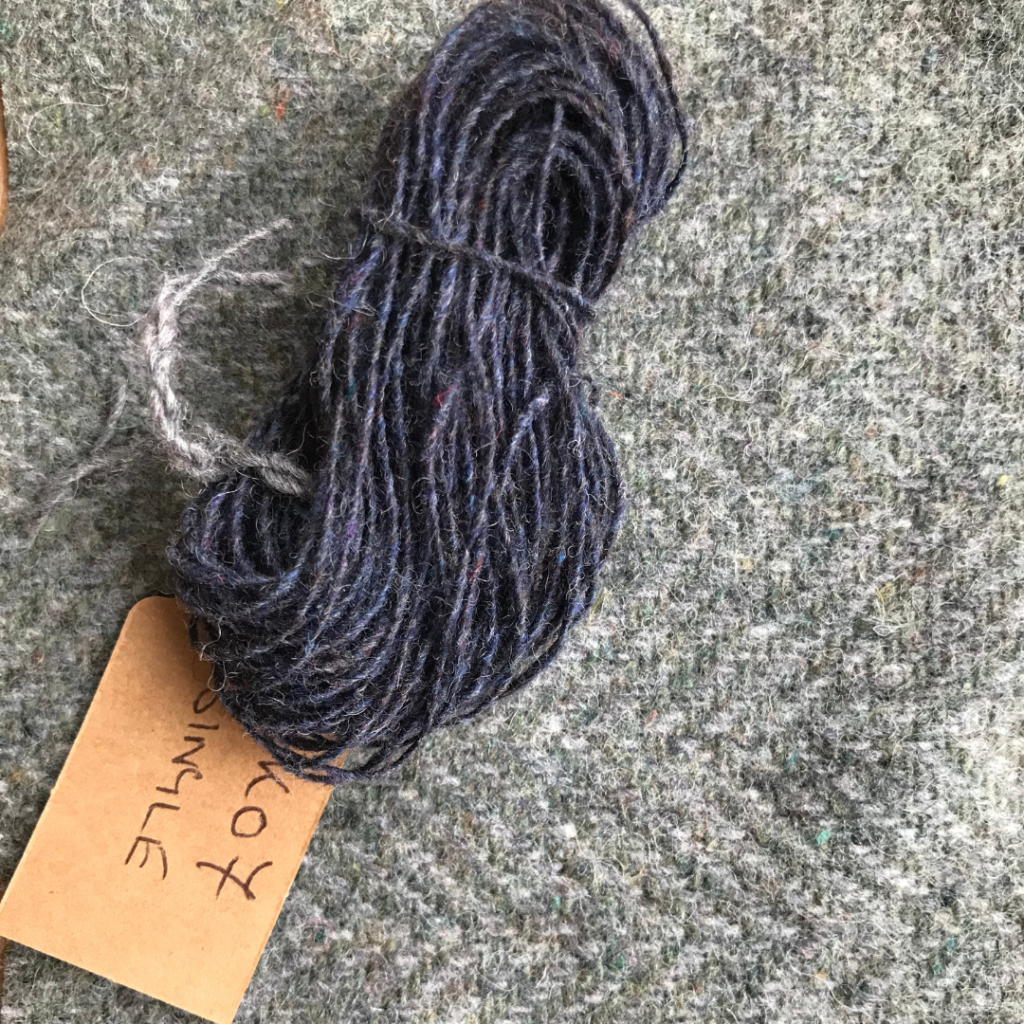

New Yarn From Old, IINOUIIO’s product

Fashion Models Wearing Shoddy Cloth 1990s.

Shoddy Script:

There’s a textile trade that has been called 200 years of secrecy and lies. – it’s played a central role in wars, slavery, affordable clothing, textile rationing, growing the finest rhubarb in the world, and the wealth of West Yorkshire. Its secrets have been smuggled across oceans and changed laws, and it has a terrible reputation:

Hanna: The machine that made shoddy had already been given the name, the devil, but the term devil’s dust sort of took off and began to be used, not just for the dust that blew up when the goods were being produced, it started to be applied across the board. So shoddy became itself that kind of excessive and useless and dirty and harmful, expression of all of the horrors of industrializing England generally

But in the age of climate change Shoddy has become something that holds tremendous promise for the future, a future in which our clothes don’t impose such a burden on the planet:

John: The world’s crying out for it, and we’re determined to not just protect the industry and the craft, but to reenergize it. And we want to learn new techniques, as well as bringing the best of the old, we want new generations, people that can bring new technologies and new ideas to train new generations, to keep this trade going and to do it better than we can, and to protect resources and, and protect the energy used to make new stuff.

Welcome to Haptic and Hue’s third series of podcasts called The Chatter of Cloth, I’m Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver interested in what textiles tell us about our lives and communities. Come with me in this episode and explore the incredible world of Shoddy and her sister, Mungo. The word Shoddy means many things, but in textile terms, it describes a cloth that includes a mix of new and recycled fibres. Shoddy is recycled knitted cloth and Mungo is recycled woven fabric.

We pick up this story on the eve of the American Civil War with a good-looking young man dressed in a smart uniform:

Hanna: So we’re looking at a carte de visite which was almost like a photographic postcard, that was, you know, becoming increasingly common in the 1850s and 1860s. and it’s a carte de visite produced in 1861 showing a very young Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. in uniform on his way, or just before he kind of went out with the 20th regiment to join the Union army in the American civil war. and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. would go on much later in his life to become an extremely important and influential member of the United States Supreme Court., but at the moment that this photograph is taken he’s in his early 20s, he’s just completed his, undergraduate school at Harvard. he’s the son of a very, famous and, kind of widely published doctor and, and writer, Oliver, Wendell Holmes, Sr. and in this, in this really beautiful photographic image, he’s seated with a kind of black curtain, sort of a black velvet curtain behind him, uh, wearing his uniform, a kind of nice-looking uniform with brass buttons and a Verizon from his, from his waist up rather high on his neck. He’s got these epaulettes, he’s got his rifle, sort of a cute cap. His hair is neatly parted on the side, and he, he looks dignified and, you know, ready to ready to do good for his country.

Hanna Rose Shell is an Associate Professor in the Art History Department of the University of Colorado at Boulder. The uniform Oliver Wendell Holmes was wearing, like most military clothing of the day, is highly likely to have been made of a mix of recycled fibres and new wool, in other words, shoddy cloth. In this case, probably good quality shoddy cloth, because this was a high-class family. But his uniform points us to the fact that when the American Civil War began, the North had a problem, a big problem. It needed to get thousands of men into uniform as quickly as possible, that wasn’t easy:

Hanna: But suddenly with the kind of beginning of this absolutely massive, civil war and civil unrest, there was a need on the part of the government and of the north for a huge amount of just kind of accoutrements of uniforms, blankets, jackets, pants, you know, all sorts of, things. And there were a number of different, big issues that arose. Um, first of all, a lot of the textile industry at that point, a lot of materials were being produced. Cottons were all being grown in the Southern states, uh, and during the civil war that sort of source for supplies was cut off to the north. Meanwhile, the Northern, um, textile mills and the woollen industry, was just completely overwhelmed by the need for uniforms. So a lot of actually a lot of uniforms, um, were, were being produced or started to be produced by some of the same textile firms and mills that had prior to the war been producing cloth for some of the slave plantations

The North didn’t make it easier for itself – it had previously established taxes on the import of British wool to protect its own industry, but it did have a small shoddy industry:

Hanna: So prior to the American civil war, this shoddy material, was at times imported, from the United Kingdom, but, but otherwise was produced primarily in the north, in the, in the kind of wool-producing regions, and it was used on the one hand for, army blankets, army uniforms, clothing suits for a working class kind of community. But one thing it was also used extensively for is it was used to produce these kinds of bolts of what was generally referred to as slave class. Um, so the several textile mills in, in New England, um, and in Pennsylvania would take these sort of second-hand wool and rags or textile clippings from the new woollen industry would shred them, would kind of re-spin them and would blend them with cotton, to create these kind of bolts, those of union cloth, which were also called slave cloth.

The problem was that the mills couldn’t produce any of this cloth fast enough and they didn’t have the materials to hand to do it, so here’s what they did:

Hanna: So, Abraham Lincoln’s first kind of declaration of war triggered, this kind of overwhelming demand for uniforms and the kind of related paraphernalia. Uh, and, and it, it led to this kind of overflow, I should say, of, of these, uh, mix materials and fabrics and uniforms that weren’t simply made of shoddy, right. That weren’t simply made of a kind of recycled material, which theoretically could have been in, can be great quality, but really low-end sort of shoddy materials. So, you know, materials were like, they weren’t even actually wool. So it was sort of dust that pretended to be wool but might actually have been paper. So really, really, low-end goods, which is to say that you have all of these, you know, these soldiers and they’re out in the woods and it’s wet, and their blankets, according to the press, according to journals, their blankets and their uniforms were kind of literally dissolving off of them.

This is one of the reasons, often overlooked, that the Civil War was the deadliest conflict in American history – there are other reasons too of course, but the uniforms the Union troops wore was not fit for purpose:

Hanna: The civil war was such a vicious and enduring kind of battle. And some of the images that have become so iconic in, in the, in remembering that the war, our pictures of union soldiers, their corpses kind of spread on battlefields, battlefields littered with dead bodies, in which we can actually see these kinds of deteriorating uniforms. So the war itself resolved with the union army winning, despite, you know, a huge number of casualties

There was a huge public scandal, the press was outraged and campaigned for reform, A number of articles survive, including this song:

Hanna: And it’s a song sort of told from three perspectives, army contractor, uh, kind of higher up in the army and a soldier. And I’ll just, I’ll just share a little bit of the lyrics because I think it gives a good taste. The coat contractors gave we’re of shoddy cloth of grey badly made and badly fashioned, much too large or small for men only for a day, we wore them and they came to pieces then bad, the buttons bad, the breaches, breaches only fit for mending. Oh, the ripping. Oh, the darning. Oh, the tailoring unending.

There were congressional inquiries, talk of criminal proceedings for war-profiteering, and of reform. These investigations became a model for future inquiries into contracting scandals. And the word shoddy escaped into the wider world and acquired new meanings.

Hanna: In the popular press and in the kind of popular imagination, the scandal surrounding this, let’s say shoddy shoddy, led to this word, shoddy becoming extremely popular and dominant in all sorts of different ways. So shoddy became a name, a kind of stand-in for anybody who was seen to be kind of nouveau riche somebody who, who didn’t have old money, but who had new money, which they may have gotten through, you know, the textile industry, for example, they would be called like a Miss Shoddy or a Princess Shoddy or a Mr. Shoddy. Oftentimes Shoddy also became a name given to immigrant communities and immigrant groups that, you know, made, have gotten in or been in these textile industries. A lot of Jews who had come in as immigrants into the U S were in the textile industry and sort would be encompassed in the kind of Mr. Shoddy, Mrs. Shoddy, these shoddy people often had Eastern European or sort of German Germanic sounding accents. So that was certainly, that was a way in which this word shoddy took on kind of larger than life connotations,

But there’s also a way of looking at this which says that America was lucky to have this technology at all. The shoddy process was invented in Britain, in West Yorkshire in the early 19th century. There are many stories about how it came about, but the man usually credited with this is Benjamin Law of Batley. There’s a blue plaque to him outside Batley Library. He put together a process in which old clothes were torn apart by powerful spiked machines known as devils. The resulting fibre could then be blended with new wool, spun into yarn, and woven into cloth. It was an ingenious way to recycle old clothing and its secrets were closely protected by law, that is until a blacksmith who had worked with the inventors of the machine, tried to make his fortune.

Hanna: What’s reported is that he shipped it out through Liverpool and was sending it to a contractor to a contact he had in New York, uh, declaring it, falsely some kind of rice threshing machine as a way to kind of cover-up that in fact, he was, he was kind of smuggling out this, this secret UK invention. He had intended to follow his machine to kind of take the next boat out, uh, and therefore be able to meet up with his smuggled machinery. And I’m sure in his mind become some kind of shoddy millionaire in the United States. But he in fact was caught and arrested by British costumes. But the shoddy picker itself had been shipped and, you know, somehow was able to connect with his contact. And then the machine ended up kind of making his way to New England and, and seeding a shoddy manufacturing industry in New England, in the United States.

Back in West Yorkshire the shoddy process had transformed places like Batley and Dewsbury. Here’s John Parkinson – a man with shoddy in his blood.

John P: So when, when Benjamin Law first sort of had his discovery and the early 18 hundreds, the towns surrounding the area were sort of very small. People were weaving and spinning in the homes, hanging in their cloth, out in the fields to dry, after to be washed up finishing. And that was that was the sort of extent of the trade. It was pre-industrial revolution as well. So it was very early on and they were competing with other areas in the country. Even there was a trade down south in the west country and in different places that were willing manufacturers and they didn’t have really any advantage over any of those. And that was where the difference occurred and the big advantage was when they were able to develop the shoddy material that could be included in a cloth and from very small hamlets, with a few people, Batley Dewsbury Morley, all those towns, and then into holy scales. They, they, they grew massive with both in population, as people went for the jobs and also the entrepreneurs that were starting up with machinery. And as they as the industrial revolution sort of took hold, they were able to develop more machinery and more efficient practices of powering the machines. And so all of a sudden a certain type of woollen cloth was becoming more affordable because it was cheaper., the forces started to use materials that were made, we lowered the costs. So as well as getting uniforms back, huge amounts of reclaimed material, were used during war times, to make clothes for the forces, especially when they couldn’t get enough wool, and it was cheaper. So as a huge trade in all that, and the historians said when the cannons roared, then the chimneys boomed, or the mills boomed, and they certainly were boom times to make fabric that was to make cloth that was cheaper. So it was hugely influential to the area and this cloth wasn’t just sold to the area. It was sold across, across the world. And it was said that largely because of some of that thread, hugely influential, that there were more Rolls Royces in the whole district than there were in London for a while, and all built on that kind of on, you know, they, all the idea that there’s brass in muck and brass being, of course, the Yorkshire term for, for money.

John was born to the shoddy trade, and some of his strongest childhood memories are helping his Dad when he set up his own Shoddy Mill in 1970.

John P: Jo it goes back, I guess to the earliest times I can remember. So in 1970, he remortgaged the house. And I remember him sort of talking to me, even though I was only 10, and telling me all about it. And typically as a 10-year-old being sort of disinterested, but not fully realized in the enormity of what he was doing. He always said, if this goes wrong, we’ll be living in a tent in a field. And that kind of sounded quite exciting to me. And my weekends and school holidays were spent helping out particularly in the first year or two when we were trying to keep the wage bill down and everything. So even though I’ve been around before then, around the mills, before I was 10, I became used to treading bails. So in the sorting room where there was often what we call rags, but today public or pre-loved garments, you know, post-consumer wool. And you climb up into the bales that were mounted with ropes on the old wood beams. And you, you tread down to make it a nice firm bale. The trick was always trailing to the corners in the middle of look after itself.): And he used to go from one bale to the other as they were empty baskets of different materials in, and then went around helping out with blending and that’s laying materials next to the fibre opening machines, what we call rag pulling. So pulling is the process of recovering fibre from garments and all the other jobs in the prism. And in the summertime sorting outside, which was lovely, but in the wintertime, not so great moving sort of skips with metal wheels across a cobbled yard with snow falling on you. And I remember one of my dad’s friends looking out from Luke says, office window two is doing this as young kids. And he said it looked like something out of Dickens.

John says in Britain too there was a sense of shame around shoddy:

John P: I think that probably, there’s always been a sense of shame in some respects or a little bit of kind of sort of playing it, playing it down amongst the people that worked within the trade. It wasn’t the best necessarily chat up line on a Friday night to say that you were a ragger or a rag grinder, how are you that kind of stuff your, your wages were below the work will be in poor conditions often dirty with the machinery dangerous that wasn’t guarded way back in the day. And it certainly wasn’t the most glamorous trade. And even within society if you were dealing with buying, wearing second-hand clothes, what we call hand me downs that was something of a bit of a shame. You wouldn’t necessarily talk about that, whereas today you’re cool, the trend if you go into vintage you’re buying but buying clothing, that’s, that’s being worn and used before. So very, very much different attitudes within society.

And that secrecy extended to the manufacturers and John says there was a great deal of cloak and dagger about the entire operation

John: And within the, within the industry many of the woollen manufacturers would try and hide the idea that they were using reclaimed wool to try and elevate their status as only using new world. And therefore that prices are higher, even if there were sneaking a bit, nearly everybody was sneaking a bit reclaimed materially, and there are stories, there are stories of woollen manufacturers, even having their bales delivered after nightfall undercover with a sort of coded descriptions on the bales. And so that people wouldn’t realize they were using reclaimed material. And also stories of competitors following the wagons around, people telling us, following the wagons down to say who’s selling to who and what’s happening. So there was this sort of idea of it being almost like an undercover thing. And to a large extent, apart from the people that live in the area, across the world many people weren’t aware that this activity sort of was taking place. And even today, even though there are other parts of the world where this happens so many times that I speak to people and they said, wow, I never realized this was possible. This is amazing. And it’s 200 years old. So it is a kind of a, it is a thing that’s been cloaked in secrecy.

One of the reasons for the secrecy is that in the 19th century Batley resembled a vision of the underworld: Here’s Hanna Rose:

Hanna: There are these, these rather vivid descriptions of the railroad tracks at Batley station in the 1850s on the railroad tracks being piled up with rags, with dust, uh, and then with the kind of blooms of gold in the eyes of the merchants doing the kind of the buying and the selling. Um, so the kind of wealth, the glitz, uh, but also the dust and the filth and the dirt and the coal, that that was needed to produce all of those things. They were, they were, yeah, the rag industry in the late 19th century was very successful and produced a lot of wealth for those in Batley.

The connection between shoddy and dirty rags was also a problem. In 1860 Samuel Jubb published a book called the History of the Shoddy Trade, and here’s how he described Batley – in an extract read by Bill Taylor.

This is the Famous Rag Capital, the tatter metropolis whither every beggar in Europe sends his cast-off clothes to be made into sham broadcloth for cheap gentility, of moth-eaten coats, frowsy jackets, reeky linen, effusive cotton, and old worsted stockings. This is the last destination. Reduced to filament a greasy pulp by might tooth cylinders, the much-vexed fabrics re-enter life in the most brilliant forms.

Descriptions like this helped form a connection between shoddy and moral hazard which were exploited by a vocal anti-shoddy movement:

Hanna: because the machine that made shoddy had already been kind of given the name, the devil, this devil’s dust referred to all the dust that blew off, but the term devil’s dust sort of took off and began to be used, not just for the, kind of the waste, the dust that blew up, you know, when the, when the goods were being produced, it started to be applied across the board. So shoddy became itself just to kind of have a dust that kind of excessive and useless and dirty and harmful, uh, expression of all of the horrors of industrializing England generally. Um, and so devil’s dust actually became a way and a topic that would be brought up by a lot of the Chartists and the Chartist movement in the 1840s in the UK, as a way to just talk about how horrible it sort of industrialism was in general, the sort of way in which that, that the shoddy industry kind of exemplified everything that was bad about these, these petty capitalists, these new companies, these factory owners needed to be controlled and you sort of actually get descriptions of shoddy mills and of the conditions of shoddy production began to be invoked as a way to kind of talk about factories more generally, being out of control, being unsafe, being unsanitary shoddy began to be criticized within that context and begin to exemplify the worst of, of that, that kind of situation.

Despite this shoddy was widely made and worn in the 19th and 20th centuries and depending on the mix it could deliver something flimsy or an excellent hard-wearing cloth. It was used for any kind of official uniform – train conductors, soldiers, sailors, nurses, policemen and firemen all wore shoddy usually without knowing. And over time the industry changed: Here’s John Parkinson:

John P: They used to say that the birds used to fly backward in Batley to stop the soot getting their eyes and all that kind of stuff until it cleaned over the years that reclamation of the materials got cleaner, the factories got cleaner and people got better at using the waste.

But the entire shoddy industry sank in decline in the second half of the 20th century as the mills in Yorkshire closed and the world moved on: Here’s John:

John P: The people wanted lightweight materials as they got warmer homes. And so when you’re spinning finer then reclaimed materials have limitations with how fine they can spin. And so there were issues that people started to use synthetics. So we had polyester duvets instead of wool blankets. And the wool blanket trade was really big, especially because those are heavier yarns to so the introduction of synthetics had a big effect and other fashion items like denim. It was also a time when, as time increased and people started to learn how to reclaim materials overseas, they could do it cheaper as health and safety meant that it was becoming more expensive for UK mills to use reclaimed materials and they have to work with higher value materials to compete. I don’t think that the English, UK Yorkshire mills perhaps kept up with technology and working with reclaimed materials can sometimes present different challenges to that. Perhaps it’s easier to work with new fibres and little by little, for lots of reasons as to say people used to have travel rooms in you know, over the on buses and trams. And then they got cars and they got heaters in the cars and all those kinds of things for warm clothing and formal wear started to decline for those reasons. And many more the shoddy trade began to decline the mills started to close, but mills were closing that didn’t you shut it. There was a general decline in the high labour-intensive industries in all the heavy industries in the UK began to decline. So, so for lots of reasons that happened until 2000, the year, 2000, the last traditional shoddy manufacturer closed.

John was working in his Dad’s company and things were difficult:

John P: We were sort of deciding whether it was, it was worth carrying on business had got so so, so low and dad got ill and we lost daddy died. And so we were left with, well, we’ve lost our leading, right? We were in this situation where we’re thinking about closing down, we’ll either after close, I will have to find a way of staying open, but we’d wrapped our brains until one time. We have that kind of a Eureka moment whereby we said, well, I’ve just been in supermarket and we’ve seen all this cardboard. It’s early days, it’s late eighties. And it’s got a trademark on it, or so mark on it, promoting it for being recycled. It’s old cardboard, and now it’s being made into new cardboard. And literally, it might seem, I feel stupid, but it was like, well, that’s what we do. So if he starts, if that’s good for cardboard, why can’t it be good for textiles? And we started to talk to some people and they pointed out that perhaps there’s a different thing to as a different cultural, sort of a connection between what you might put in a cardboard box and what you might wear as clothing and people were saying, you know, even then you don’t want to be promoting that. People have worn it before. And to which I say, well, when you use new wool a sheep’s worn it before, so like, what’s the difference?

For a time the business flourished as one of the first companies openly promoting themselves as a recycling venture, they were way ahead of the times and became one of the first to start recycling cashmere, denim, and polyester. They supplied yarn to clothing manufacturers and they were a big hit with catalogues from charities like Greenpeace and Oxfam. But it didn’t last and in the mid ’90s John closed the doors and had to find another way to make a living as a teacher.

But you can take a man out of shoddy but you can’t take the shoddy out of the man – and nearly thirty years later – John decided to give it another go when his daughter told him he held part of the puzzle of how to stop textiles ruining the planet.

John P: But I went back into the trade and people that I hadn’t met for 30 years, the few that were left and started talking to them, and it was, then I found out that there weren’t any traditional Shirley manufacturers left, and there’d been a generation since the last one in 2000 closed. And that the woollen mills didn’t know how to deal with it anymore. There were loads of myths about what was possible and what wasn’t possible. And I kind of, there was a great sadness that, and also a desperation that, well, we couldn’t get involved now because the infrastructure is not there, but at the same time, there was an excitement and an opportunity that, well, there’s no competition. So if we could open that up, the market stronger than ever now, maybe we could do this thing again.

So it was off to Companies House for John to register a new shoddy company – one this time that has a weird name IINOUIIO – and a wonderful explanation behind it:

John: I’m always telling the kids about not to give in and tenacity and all that kind of stuff. And the idea that waste materials are not really waste materials, it’s a raw material. That’s limited by our imagination and it can be used for new stuff, but how do you get all that into like a trendy name, I’m not sure where the analogy to trend your name, but I’m always telling kids it’s never over until it’s over, which for international listeners is, It Is Never Over Until It Is Over. And I went to Company’s House to start the business thinking I’ll make a contraction, I’ll make an acronym. And so I tried to do that with a single I. It’s never over until it’s over and amazingly somebody else has a business, very close to that name. So I did the full, it is never over until it’s over, and put that into the Company’s House thing. They said, yeah, you’re crazy. Nobody else would have a name like that for a new company and clicked the button and become IINOUIIO.

At the moment, John’s idea has survived the pandemic. He has secured the grants, bought the machines and is ready to make new shoddy – he knows there’s a market there for it – all he lacks is somewhere to site his machines and run his business, and time is getting short before the offer of funding runs out. Getting to this point has been an enormous effort and risk for him and his family but his zeal is undimmed:

John P: But even though I’ve given up my job as, as a, as a teacher to focus on this full time, we’ve been to lots of different UK manufacturers to say, we can do this job for you. Now we can take your waste. We can be a service to you, both for research and development, but for the first time in a generation, we can take your waste and repurpose it for you. So you can either put it back into your hopper and use it again. Or if you haven’t got that facility, we can make new yarns and fabrics to offer as ranges to your customers for waste that previously might’ve been landfilled burned, sold to the waste man. And you’ve no idea what, what he’s going to do with it. We can, we can provide this solution for you. This is like such a joyous thing that we can do when it’s like so amazing that we’re going to be able to, we’re going to have to provide the service to the UK industry in the back in a trade, be able to follow our passion again.

He’s not there yet but the old gleam is back in his eye. This story though has some threads to darn in: Oliver Wendell Holmes survived the Civil War, although he almost died from his injuries. He went on to become a distinguished Supreme Court judge. Over 40 years later a case came before the court about the transport of mattresses across state lines in the US. Mattresses usually are stuffed with shoddy. The other judges couldn’t see a problem but Justice Wendell Holmes could.

Hanna: Oliver Wendell Holmes, who had had this very wrenching and memorable experience as a soldier in the civil war, had seen first-hand that kind of state of soldiers having to deal with these very like shoddy shoddy-uniforms, was confronted with this case. And it was in 1926, he delivered a kind of searing dissent. The court as a whole basically decided that there was no problem with interstate commerce in this case. And that there wasn’t necessarily a problem with the cleanliness of the mattresses, which was what all the Wendell Holmes was really concerned about. And Holmes delivered a really searing dissent basically, just decrying, even the possibility that shoddy materials could be anything but diseased, but there was no way to know that shoddy, that second-hand goods could be anything, but sickly but ill. So it seemed that he really had brought over these kinds of memories and these associations from the Civil War, to his attitude and approach towards ruling when he was in this very kind of powerful position.

And I promised you Rhubarb as well. Yorkshire is the producer of the world’s finest rhubarb in an area not far from the old Shoddy towns called the Golden Triangle – part of the secret of that Rhubarb was the fertilizer that they used on it which was, of course, – nitrogen-rich dust from the old shoddy mills. If John succeeds in getting the space he needs to make shoddy again then the rhubarb may find a new supply of fertilizer, but for now he’s living on hope and a vision that he has a way to make a real difference to the planet:

John P: it’s absolutely the same kind of joy. I mean, I watch the processes happening right from the sorting and then what we call pulling the shredding, the opening out, then as it goes from blending into carding and spinning, and then making into new stuff, and I’m watching it, and it’s, it’s just a magic trick. Like, even though it’s all I’ve known and I still, you know, standing gazing wondering, can we do that? Can we turn this stuff into this? How is this happening in front of me, eyes? And that, you know, just the excitement that when you get a new project to work on it, a new yarn to make a new colour and you, that just, just the potential, just that, you know, being involved with this amazing transformation is, is just a joy and a privilege to be part of.

Thanks to Dr John Parkinson for sharing his passion for shoddy – if anyone knows of someone who want to house a new shoddy business – get in touch with him now. To Hanna Rose Shell for her research and expertise – her book Shoddy – From Devils Dust to the Renaissance of Rags is a great read and you can find it in the Haptic and Hue bookshop, as well as a curated selection of the best textile books in print recommended by listeners to the podcast – there are some great presents there and every purchase helps support this podcast at no extra cost to you.

Lastly thanks to, to Bill Taylor of the Lark Rise Partnership who produced and edited this episode. We will be back next time looking at what samplers tell us about the women and girls who made them and the times they lived in. Thank you for listening and thank you as ever for supporting this podcast via the buy me a coffee button – I appreciate it.