Samplers

And The Hands That Made Them

Episode #25

This episode of Haptic and Hue looks at how women in the past were united by their ability to use a needle skilfully. From the grandest monarch to the youngest scullery maid they could all sew. It was a common language – one that they shared and were fluent in. They were often better at forming letters and numbers with a needle than with a pen and pencil. It gave them a way of thinking that we have all but lost.

But what they sewed divided them, and never more so than in the 19th century when middle-class women were urged to take up the new idealogy of domesticity and create an idealised home for their husbands and families, places of rest and leisure, where berlin wool-work, firescreens, and antimacassars had their place, or where female family members gave hand-stitched gifts demonstrating their skill and devotion. Even Queen Victoria stitched and gave away her handiwork. At the same time working-class women were being prepared for an entirely different path – a life of plain sewing, of earning their living with their needles – working as seamstresses or mending clothing, stitching other people’s initials onto table linen and family laundry. We can track these stories through the samplers they made – although we cannot always put names to the work.

This episode runs for 41 minutes.

Joanna Teague is a community artist and researcher of historic embroidery. You can find her on Instagram @thingshandmade.

Roisin Quinn Lautrefin is an academic and teacher in Paris – if you are interested in more on material literacy – here is an academic article she wrote about it. It is available in both French and English.

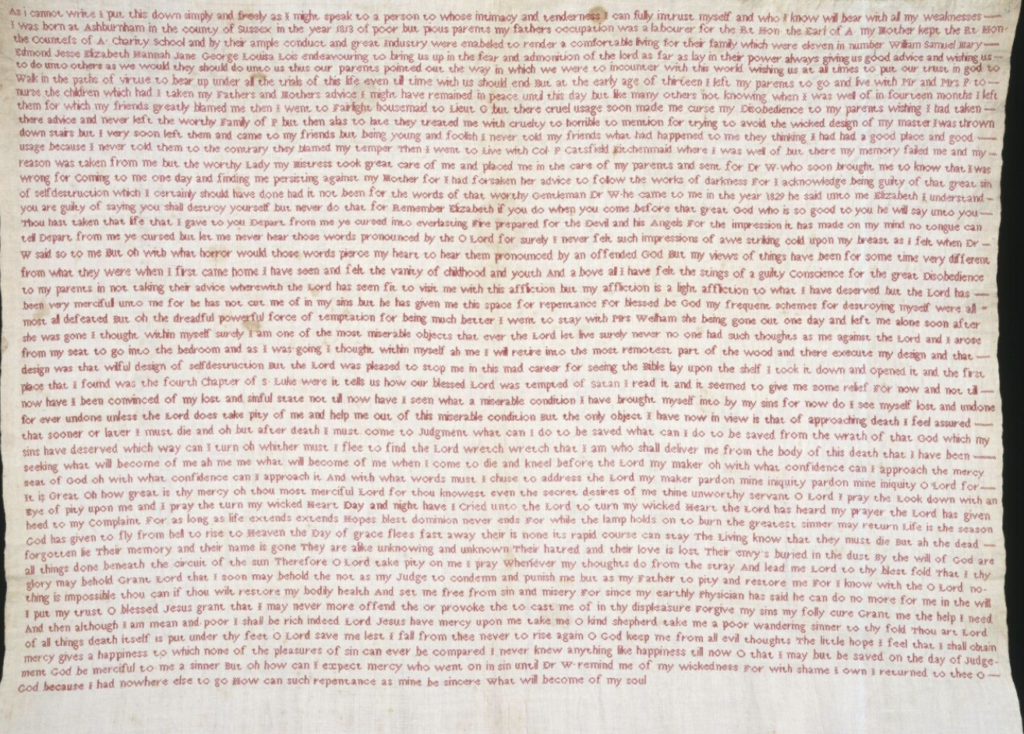

If you would like to know about Elizabeth Parker’s sampler the V&A has more details here.

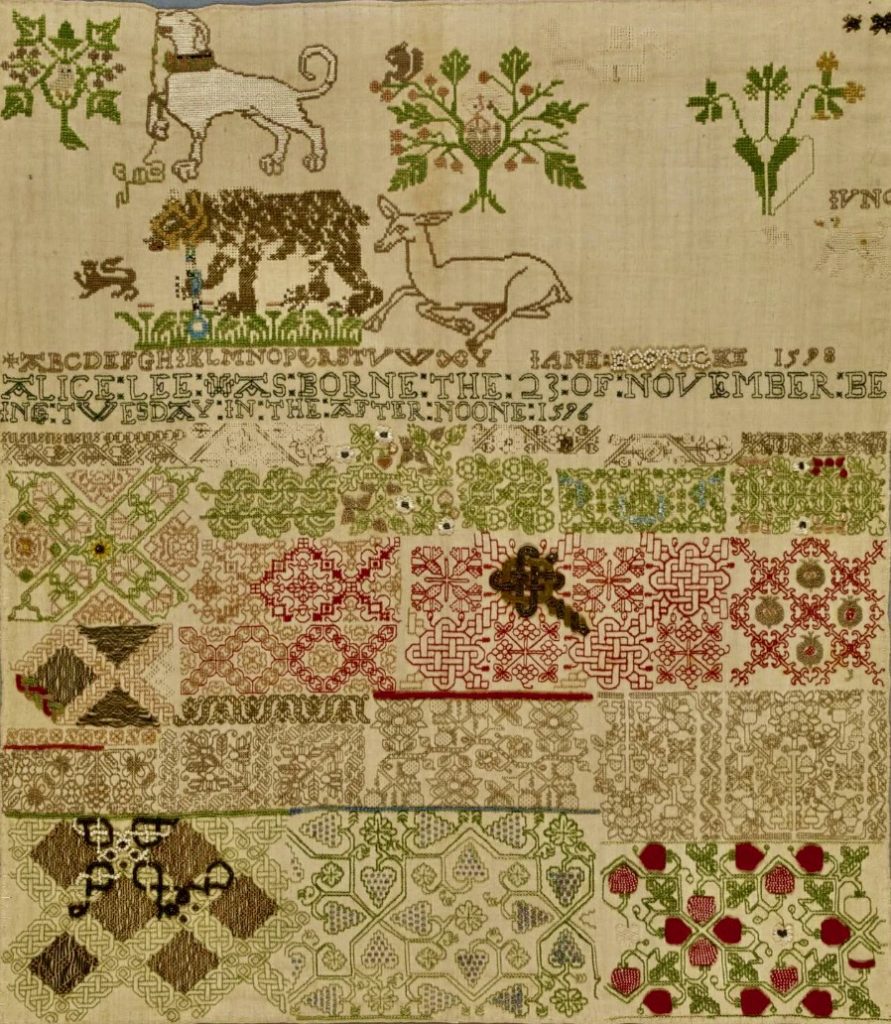

And if you would like to know more about the Jane Bostock sampler there are more details here

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Joanna Teague

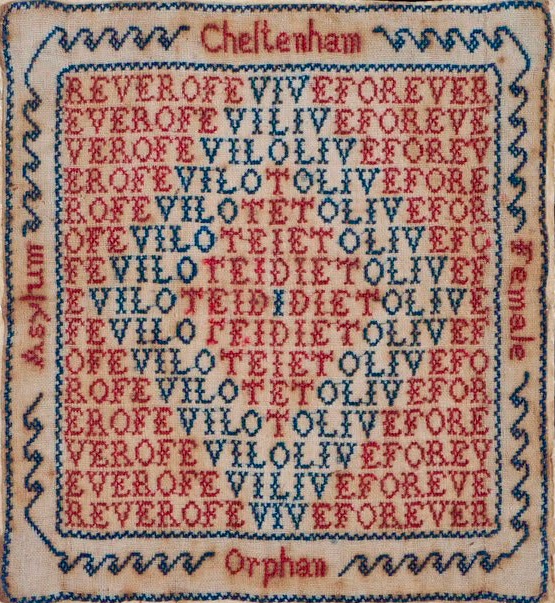

Acrostic Sampler – I Die to Live Forever

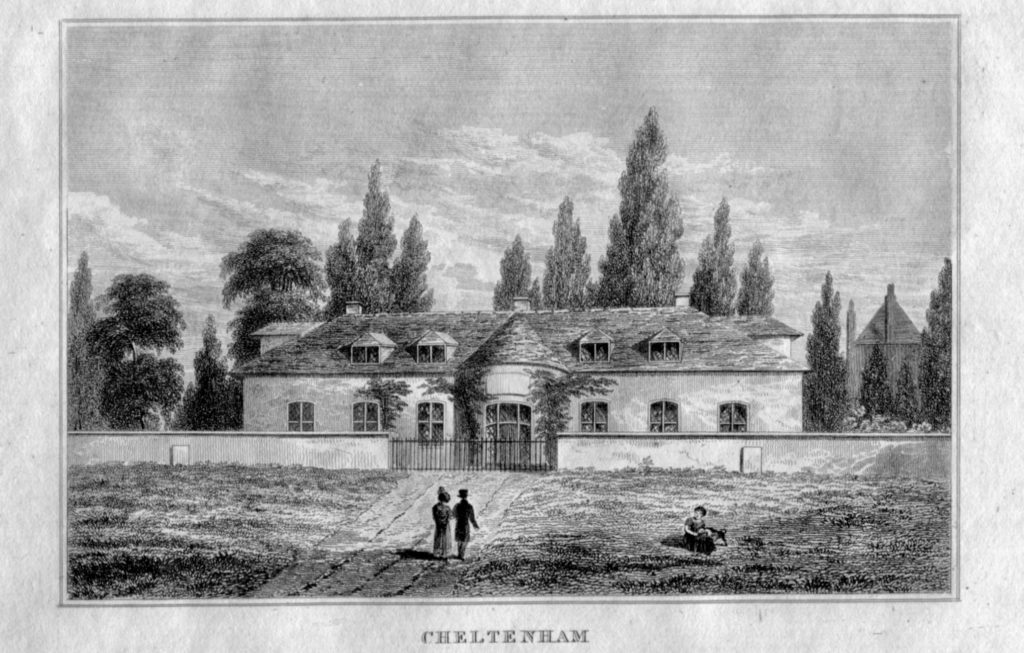

Cheltenham Female Orphanage

Roisin Quinn Lautrefin

Plain work – every day stitching

Learning to Darn – preparation for a life of service

Fancy Work Berlin Woolwork

Fancy work

Fancy work, hand made antimacassar

Sampler from 1598 sewn by Jane Bostock, V & A Museum

Elizabeth Parker’s Sampler or Textile Story, V&A Museum

Queen Victoria – who sewed, embroidered, knitted and crocheted

Samplers Script

There are some textiles that give up their stories easily, look at them, hold them and they will tell you what they are and where they come from. They will probably give you clues about who made them and what this cloth meant to them. Others are harder to understand, we think we see them, but everything is not quite what it looks. There is a surface story and then a hidden one that sits behind it. The textile that we start this episode with is one those:

The sampler I’ve chosen is quite small. It’s only about 10 centimeters by 10 centimeters, about four and a half inches square. And I first saw it in the middle of Cheltenham. There’s a small museum, a Victorian House museum that was once the home of Gustav Holst, the composer. If you visit and climb to the top of the house, to the nursery, there you’ll see small embroidered samplers, as you would often see in a nursery, the tiny stitches are embroidered in black and red with a complicated acrostic, that interlocks across the design, the words interlock to say I die to live forever and it’s repeated vertically and horizontally. Around the outside of the square are the words Cheltenham female orphanage asylum. And there are further scrolling angular, borders that frame the piece. When you see it, it does look rather tangled, massive letters rather than the usual straight lines that you see on a traditional sampler. It’s a typically religious Victorian saying, there’s no name of the maker. There are no pictures, there’s no decorative element. Other than the use of the acrostic, the colours are just black and red with the name of the orphanage.

Joanna Teague is a community artist and researcher of historic embroidery and she lives in the west country of England. She has been studying samplers made in orphanages and she suggested this episode to me as a listener to Haptic and Hue. It took me time to understand what she was getting at, but I got there in the end, and I think it is a fascinating tale. It made me think harder and deeper about stitching and needlework, about what it has meant for women and how it has defined their lives, helping us to unpick just a few of the layers of new meaning that textiles can show us. I have posted a picture of the sampler Joanna is talking about on the Haptic and Hue website. It caught her eye in particular as she realised that she had seen one exactly like it before.

This sampler I’d seen before in October, 2018, I’d seen on an auction website, a sampler sold for 14,000 pounds. That’s just under $20,000. And with no date, no maker’s name and no history attached. That was really was quite a price for a small sampler. The Cheltenham orphanage samplers are rarely sold. It’s quite a difficult thing to value. And so really the sales report records it as a sleeper that was in high demand. That’s the piece that really started my interest in samplers with the same design in two different places, that started my interest in Cheltenham orphanage pieces. I was fascinated by the idea that it’s sold for so much when there was no name on it. I work for Cheltenham museum, the Wilson museum and chaplain on the children’s workshops there. And in my work I’d seen pictures and photographs of the girls at the orphanage, but this was the first time I’d really seen those distinctive samplers. They really are quite an unusual design. It seemed an incredibly high price for such a small and anonymous piece of work. And as I started to research, I found more and more examples of the same piece and then variations on the design again, anonymous, from Cheltenham orphanage that started to intrigue me as to how and why these had been produced.

This idea of several samplers, each exactly the same with no name and no date intrigues me too. It goes against so much of what we think of as a sampler, the kind that many of us will have seen or had on family walls, with names of female relatives from the 17 and 18 hundreds showing their skills in wobbly stitches, letter,s and numbers. These are often precious links for us with past female family members, ones that carry a strong emotional connection. We cannot hear and sometimes we cannot see these women – but we can touch or view cloth that they have worked on and the words that they have made. But these samplers are different. Joanna says we know nothing about who made these samplers or what became of them, but her research leads us back to another age when opportunities for girls were not the same and the choices for those who came from poor backgrounds and had to earn their living were limited and the dangers intense. The key to this lies in the orphanage system. Cheltenham is a well-heeled town in the West of England and the Female Asylum, as it was called, was set up right at the start of the 19th century.

This asylum was established in 1806 and it’s an unusual asylum orphanage, because it was patronized by three different Queens. It started off with Queen Charlotte, the wife of George the Third, both of which of course are known for their patronage of the arts. And establishing that tradition, that the British monarchy continues today, of charitable work. The orphanage was originally a school of industry, a form of charitable education that took on destitute children and taught them an industry, some way in which to support themselves. Cheltenham is quite an unusual place. It had been a very small town up until about 1716 when famously the local mayor Henry Skillicorn found the first well, the first spa, the first point at which the mineral waters of the town became famous, people would come to the town to take the waters through Georgian times. It was a very popular Spa town, rather like Bath, but on a smaller scale. When a town grows quickly, there often is this wide expansion between the rich and the poor and the issues that come with urban living. So, it left many families struggling. This combined with the concerns over the need for domestic staff to support that growing tourist trade gave the right circumstances for the establishment of a school of industry. We don’t know a lot about the early establishment, but we know that money was raised by public subscription. And there are guides to Cheltenham such as in 1807, where the description gives a committee room, a schoolroom, small kitchen pantry, scullery, dormitories to sleep in, very plain furniture, brick floors, small beds, with flop mattresses. There were 40 public subscribers supporting 12 poor poor girls with the aim that they’d be trained into domestic service to help with the shortage of staff locally.

The new asylum was a success and very quickly doubled its intake and renamed itself an orphanage.

It now supported 24 girls, orphans or half orphans. There was a uniform to be worn, a brand search gams straw on its capes, black shoes, stockings, white tippets, checked bib aprons, and Duffel coats. The emphasis on education changed. And now the girls started and ended each day with a religious service. And then there was reading and spelling practice each day. During the last year, each girl was tested on her Bible knowledge. However, much of the day was taken with the task of learning all the skills needed to become a useful domestic servant. The girls learned the tasks through caring for each other at the orphanage, cleaning and lighting the fires. They were regular routines that week. So Thursdays was always cleaning the iron and the grates, all the skills that were needed to enter a local household. They learned to plain sew which was so important in all households they needed to maintain the clothing and furnishings of a household.

The future for these children was to go into domestic service, with long hours and poor wages. At best they might become lady’s maids in a great house, think Downton Abbey at the top of end of the social strata of servants. It seems grim to us and it’s not what we would want for our own children but at the time it was seen as an opportunity, Girls arrived at the age of seven or eight in the orphanage and stayed in the early days until they were 13 and then later until they were 18.

Competition for the places was high within this particular home. Children, girls have to be orphans or half orphans, although there is in the records, talk of girls being able to pay to come to it. So, if they’re an orphan or half orphan already in their family circumstances, they’re going to be struggling. Interestingly, the report does ask that girls have not received poor relief, they weren’t allowed to come from the workhouse. They couldn’t receive any parish relief. So we’re talking about a level of strata within the working class who are in modern terms, the, just about managing, in that they’re managing to keep life up and then circumstances, becoming an orphan, obviously changes drastically for them. They have to appear, they have to present the marriage certificates of their parents. They have to represent, present the baptismal certificates. They need to report from a local Vicar saying what an upstanding family they are. So we’re really not looking at girls the lowest or those that have fallen through to the strata that is in the workhouse. We’re really looking higher up than that. We have got Mayhew’s reports of the London poor which give us great documents about how people were living, but his focus on the very poorest in society. That’s probably not who is coming to the orphanage here. We’re talking about the daughters of tradesmen. We’re talking about the daughters of craftsmen who were falling on hard times.

The records show that girls came not just from the surrounding areas, around Cheltenham but from as far away as Glasgow and Cornwall.

It was a safe place to come and be. It was a place where they could learn a trade and move on in life. There was a very good possibility of you finding a good household in which to become a domestic servant. Many of the girls went on to the homes of the subscribers. So there is this idea that middle and upper-class people are creating almost factory fodder. They’re creating an environment in which the girls learn the skills that they will need for domestic stuff later on. But it’s a safe place for the girls to come to. It’s an upstanding moral house in which they can be. They know they’re going to be fed. Life is going to be poor. Life is going to be no luxury, but that’s going to be better than the alternatives that were available. We see in some of the reports that girls repeatedly apply to get into this orphanage. There is some status to being in there. You’re going to be guaranteed a job when you come out the other side.

And part of your training for that life seems to have come with a loss of identity. We have very little idea of what became of these women and what happened to them, Joanna says that sometimes she is able to track a young woman into her first position, but after that loses the trail, which is where these unnamed samplers come back in. The orphanage was supported by charitable giving, but still the orphanage needed to bring in some extra funds and for that they put their charges to work:

The orphanage used an early form of social enterprise. So they took in sewing. We actually have price-lists for the sewing and mending that the girls would complete. You could send in your sewing and mending ready for the girls to complete. And it was part of their training for the domestic service that they were very likely to enter after the orphanage. There was also an annual Bazaar for which the girls made small saleable items and these samplers were what were being made for that annual bazaar. They also made small pin cushions. It’s likely that they could have made other things as well. But the only things that we found that probably come from those bazaars are the pincushions and the samplers, because they are named as Cheltenham Female Orphanage Asylum.

There seem to have been about eight variations down the years of different samplers, all bearing improving mottos that were selected from Victorian periodicals and magazines. They tell us very little about the girls themselves, who remain silent here, and much more about the values of those who funded them:

Absolutely. Absolutely. So when I first started to study their samplers, I was hoping that these samplers would tell me through the iconography through the symbols would tell me more about the women who made them, the girls who made them. But I think in reality, it tells us more of the values of those women who were running the orphanage. So Cheltenham at that time was known as a bit of a party town. People would come for their holidays, enjoy it. It didn’t have the best of reputations. We have a famous horse race that is still run today, The Gold Cup, which was originated by George The Third, he donated the Cup. And so gambling, partying was, there was a lot going on in this town. And as I said before, that, that gap, that urban gap between the rich and the poor is having an impact on people. And so the well-to-do women of the town wanted to resolve this issue over domestic staff, but it also gave them chance to show their philanthropy, their generosity, that Christian spirit, another vital part of the women’s values of the day. So we have two committees running the orphanage. We have an all-male committee, which is the committee of the superintendents. They run the building. They look after the money. Then we have an all-female committee that run the day-to-day running of the household. Some of these are subscribers. Some are simply doing charitable good works. But really these samplers show us the values of that daily committee, the values that they wanted to show about the orphanage, the samplers are small. They use a small amount of cloth, so they are good value. They are clean. They’re neat, they’re precise. They’ve got a Victorian moral on there to show the good value. These samplers really show us the values of the orphanage and thereby the women running the orphanage, rather than what the girls want to express. They want to show people that your domestic staff that come from this orphanage will be neat. There’ll be organized, there’ll be precise. There’ll be careful with their materials. And that’s one of things we can read from these samplers.

Joanna believes that the women and men who supported the orphanage were doing two things, they were making themselves feel better about life, which has been one of the great drivers of philanthropic and charitable giving down the ages, but at the same time they were also keeping a relatively small number of girls safe for a period of time:

I think there was a touch of both. I’d like to, I’d like to think that there was a touch of both. I think there is both a sort of form of public do-gooding, that this is a nice, appropriate charity to get involved in. The girls will be clean. There is no danger as there would be with the workhouse of picking up some horrible disease. In order for the girls to attend, they have to have a certificate of health to show that they’re not arriving with anything that could be passed on. So I think it’s a very right and appropriate charity for women to get involved in. I also think that they are preventing these girls from entering the workhouse. They are preventing these girls from slipping any further with their morals or values that is certainly how they see it as doing. But I do think they are genuinely are looking after the girls, and we have no reports of poor treatment. In fact, the orphanage was regularly open to visitors. We have no reports of poor treatment from them

The point for me is that with a contemporary gaze we might look at these samplers and see a personal and emotional connection back to the women who made them, but in reality, although she worked the stitches, she did not choose them and in them, she is not expressing any personal choice of her own, and in that sense, these particular samplers are impersonal – and show us why it is so difficult to know the lives of working women in the past because so often they were effaced. There is though one sampler that utterly breaks this convention. By some miracle, it has survived and is now in the Victorian and Albert Museum in London. It is a stitched story, really a howl of pain and anguish from a young woman servant called Elizabeth Parker. It begins with the words

“As I cannot write I put this down simply and freely as I might speak to a person to whose intimacy and tenderness I can fully intrust myself and who I know will bear with all my weaknesses….” It goes on to tell her story of being a young servant and moving to a new household where her male employer assaults her and then throws her down the stairs:

So Elizabeth Parker’s work, and there’s some people call it sampler. Some people call it a diary. I like to call it a stitched text and it was made we think in the 1830s it’s an extraordinary artifact. It’s very unlike other samplers of the period. It has, you know, no alphabet, no flowers, no decorations, no variations. It’s just 46 lines of tiny cross-stitch letters in red. And so it’s extremely austere and simple which is striking for the period.

Roisin Quinn Lautrefin lives in Paris where she is an academic and teacher, specialising in Victorian women’s writing and in their needlework and craft practices.

And if you look at the text itself, it has no paragraphs, no punctuation. The capitalisation is quite unusual and erratic. And so it’s an extremely modern text. It reads like a stream of consciousness. And so about Elizabeth Parker: we read in her own cross-stitch words that she was born in 1813. She was one of 10 siblings in a family that she herself describes as poor, but pious, her father was a day labourer and she lived in a village called Ashburnham in East Sussex. And at the age of 13, she left home to enter service in a home where she was well-treated. And then four months later against her parents’ wishes, she left for another position as a housemaid where she faced what she calls ‘cruelty, too horrible to mention’. And scholars have interpreted this as sexual abuse. She eventually managed to escape and found a new position, but she fell into a deep depression and even attempted suicide. And this is something that’s she’s written too, you know, in her, in her sampler text. It’s an extremely introspective text. It doesn’t follow the codes of at samplers at the time, which were made for display. It’s an extremely private text and that’s why when reading it sometimes you perhaps can feel slightly uncomfortable. It’s almost like reading someone’s private diary.

And to me one of the most unusual things about this piece is that it is beautifully stitched and yet in stitches, she says she cannot write. This is the reverse really of how we would see things today. Women in most cultures are highly literate – but would find it hard to execute such extensive and beautiful stitching, which made me wonder if stitched words have an extra power and emotional intensity that written words lack:

That’s is a very interesting question because she says in the first sentence that she cannot write. So it’s extremely enigmatic, it’s extremely puzzling. And, you know, to describe yourself as illiterate, right when she’s, so obviously stitching these very words. Now I would say that she considered herself unable to write with a pen and paper with the ease and style as a man would have done. And, you know, after all, women have been historically marginalized from print culture and discouraged from writing in the 19th century, we have example upon example, and she probably viewed fabric and thread as an alternative space of discourse with which she felt more familiar and comfortable. Texts and textiles share a common etymology. So we know this, you know, and the continuity between writing and stitching is very natural. And I would add that at the time Elizabeth was stitching her memoirs paper was still being made from rags. So you could be very possibly at that time, you could very possibly be reading about a dress on paper that had been a dress in a former life. And the Victorians would have been very, very aware of that. And so by stitching words on fabric, women were able to engage in a specifically female form of discourse with its paradigms and its language, and its own grammar and so on. Needlework is extremely varied and codified and complex semantic practice. You needed to be fluent in Needlework in order to understand it. And this is what I call textile literacy. And so Victorian women who were instructed in textile literacy from a very young age would have understood stitched work and how it works and its codes.

This is a form of textile communication or material literacy that we struggle to understand today but in the 19th century, Europe and North America women would have been very aware of – to the extent that it added an entirely different layer of understanding to photos and stories by authors like Charlotte and Anne Bronte, George Eliot and Mrs Gaskell. Here’s Roisin again:

So 19th-century needlework was divided, you know very broadly into two practices. There would be plain work on one hand, which was the making the hemming, the mending clothes, and household linen. And then, on the other hand, you’d have fancy work, which was decorative stitching, such as embroidery or crochet or lace making. And the needlework that you did was directly linked to socioeconomic status. So in middle-class households, plain sewing would normally be left to the servants or outsourced to seamstresses in sweatshops. And the ladies of the house would engage in fancywork and making decorative items for the house.

And The Industrial Revolution emphasised this divide.

In the 19th century. Cities became increasingly busy and noisy, grimy and smoky. And this led to the relocation of middle-class households and families to the suburbs. So suddenly middle-class women found themselves on the periphery of cities and without remuneration, without paid employment, remunerative employment. So needlework provided them with an occupation, something to do, a socially approved occupation. So that’s one reason. And also as a result of the industrial revolution, we have the growth of the ideology of domesticity in the 19th century, which meant that middle-class women were expected to curate and fashion cozy homes, ideal homes for their husbands to return to after their day’s work. And they would do this by hand-making decorative items, embroidered slippers and tapestry, and Berlin wool work and antimacassars, and all these objects. And then in the 19th century, another thing that happened is mass production. And so because of industrialisation more and more items were mass-produced in factories. So we think of course of bolts of cotton, but it was buttons and needles and lace and patterns that were being mass-produced for the first time. And by the second half of the 19th century, you even started having needlework kits that started appearing on the market. So the industrial revolution and the mass production of goods instead of bringing domestic needlework to a halt it provided new possibilities for fancy work, for decorative needlework. And by the 1840s, by the mid-19th-century fancy work had become an absolute craze and it was a huge economic success. So I think these are the reasons why this divide was particularly salient in the 19th century, why it became so stark.

Joanna Teague spotted a good example of this kind of material literacy in Charlotte Bronte’s great novel Jane Eyre

I think we’ve lost some of our material literacy that is written about in those books. I think we can understand some of the basics, but we’ve lost some of the sophistication in there. They can often appear as a casual throwaway comment about picking up a piece of needlework or putting down a piece of needlework. In, in Bronte’s Jane Eyre, Jane positions herself with a piece of needlework when Rochester comes in after one of the fires, she picks a piece of needlework. She has been seen using that piece of needlework. And that is to show that she is a lady. She is no longer a member of the domestic staff. She has developed beyond that. So they are using these, they’re writing these paragraphs to tell us something, give us further into insight into a character or personality.

It gives us a clue to the mental framework of another age, we can never truly enter into their ways of thinking but textiles and an understanding of needlework can help us approach that, and whatever your class or occupation Roisin makes the point that the needle was a great leveller and that all women from the royalty to the poorest in the land learned to sew:

So I would say that needlework bound women in a common economy of textile. And obviously, their lives were extremely different, but all women, had this shared common experience, both social, geographic and historical because throughout history sewing has been considered has been envisaged as women’s work and women have sewn because they were women. Now this link between femininity and sewing was accentuated in the Victorian age, but it is something that’s that resonates with history. So the Victorian girls who had been taught textile literacy from a young age would have approached the world through a bilingual perspective, understanding the language of fabric as well as print.

And as I go back and re-read some of the great Victorian classics it’s a way of reading I will be taking with me to see if it can shed some fresh light on some old favourites. The other factor this has pointed up for me – which I have never properly seen before is the marriage between the needle and morals: somehow the two become confused and someone who could stitch well was assumed to be respectable, clean, and to have a high moral standing, and I think it is something that came down to us well into the 20th century – I struggled learning needlework at school – let us be frank I couldn’t do it – and this was seen – even for my generation as a deeper stain on my character than being rubbish at maths.

Do you know that in the 19th century Queen Victoria, so who was a great lover of fancy work, had photographs taken off doing crochet or embroidery or whatever decorative needlework she was doing. And this was viewed as a way of extolling virtuous femininity and an example for Victorian women in the 19th century. You know, so from the Queen to the scullery maid, all women did needlework. So sewing was considered to be women’s work and women’s sewed because they were women. And so, in other words, needlework was the signifier of bourgeois femininity in the 19th century, the mark of the respectable woman. And so the practice of needlework in the middle and upper classes was more about inculcating, industrious femininity rather than the end product. In other words it was a fairly performative practice. And I would say that the revival of domestic needlework today in fact would have some resemblance with the, the ethics of needlework in the 19th century in the sense that nowadays in industrialized countries I think it’s safe to say that all domestic needlework nowadays is fancy work. It is not the norm to produce our own clothes, and if we do it’s is a choice and a fairly privileged choice because it’s much cheaper to buy cheap clothes than to make your own clothes. So people often women still today, some needlework practitioners today, craft practitioners produce handmade items often do it out of thrift. Also with regard to the environment they’re rejecting mass-produced items. So it’s also something very performative, you know, a way of showing you that you have a desirable, moral code if that makes sense.

Roisin’s point is that in making or knitting our own clothes today we are in part making a powerful statement about our own values – just as surely as they did a hundred and fifty years ago. But the resonance for me in this story is the understanding that the women of the past often spoke much more articulately through the needle than they did in any other way, and if we to understand them we need to do so by understanding through that work. They told very different stories, tales of creating homes in new suburbs or demonstrating their skill and diligence, or of learning to form their letters and numbers. Working-class women often told other peoples’ stories, not their own: laundry labels, repairs, seamstresses in sweatshops sewing dresses. Pick up a piece of old linen and see the stitched initials on it, or the old laundry mark: I wonder now who made those stitches, is this the only memorial to a woman who left no other mark, whose name and fate we will never know? I have just finished reading a good book called The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams in it there is an exchange that expresses this beautifully. It’s between a servant, Lizzie Lester – an orphan who has no formal education and Esme the girl that she looks after: Esme asks:

“Why do you do Needlepoint Lizzie?”

“I guess I like to keep me hands busy”: Lizzie said: “And it proves I exist.”

“But that’s silly, of course you exist.”

“I clean, I help with the cooking, I set the fires. Everything I do gets eaten, or dirtied or burned – at the end of a day there’s no proof I’ve been here at all.” She paused, kneeled down beside me and stroked the embroidery on the edge of my skirt. It hid the repair she made when I tore it on brambles.

“Me needlework will always be here” she said. “I see this and I feel, well, I don’t know the word. Like I’ll always be here.”

Nicely put – And that other Servant, Elizabeth Parker, survived her rape, her breakdown and her attempted suicide, we now know thanks to recent research that she became a school teacher and lived until the ripe old age for those times of 76.

Joanna Teague says her research into samplers has sharpened her understanding of what she is looking at.

It has made me change. I also have a sampler on the wall. It’s not a relative, but I have a sampler on the wall and it, I now connect to that in a different way because I see it as a much more middle-class piece of work. I can see the difference now between those working house samplers, those school samplers and those middle and upper-class samplers that as that, to show us the values of the women that made them that when, when [inaudible] talks about someplace in a book in the subversive stats, she’s often talking about that those middle-class samplers where women had a choice and now I see much more connect with those samplers where women did not have a choice if they did not learn to. So how were they going to make their living? How were they going to survive in a society that wasn’t going to value them for any other reason? Prostitution is the only alternative that sewing is an important part of life for which they had no choice over we today. We’ll sit. And so, and it’s a relaxing, mindful exercise that allows us to explore our creativity, that women were sewing because they had to. So it was as essential to their life as eating is breathing in order to keep the household furnishings repaired in order to make their living.

Thanks to Joanna Teague, whose idea this episode first was. She has guided its creation, interesting me in her work on the Cheltenham Orphanage in particular, and in samplers in general. She has taught me that there is more to them than meets the eye. I have enjoyed the journey: Thank you Joanna, thank you also to Roisin for contributing her knowledge of samplers, and her thoughtful analysis to this episode.

If you would like to see pictures of the samplers and needlework we have talked about in this episode go to www.hapticandhue.com/listen where you will find show notes, a full script and links to books and articles that I found helpful for this podcast. If you feel able to I’d be delighted if you could leave a rating or a review for Haptic and Hue on the platform where you get your podcasts, or if you felt able to Buy me a Coffee, it all helps. And Thanks for listening this time. Next time we have the last episode in this series, Series 3. It is a special tale and has all the hallmarks of a great textile story, a quilt that is 80 years old and was made by unknown hands to send to unknown people as an expression of love and care, from one nation to another at a time of great need. Hear the extraordinary story of the Winona Circle quilt from Canada next time. Until then – if you are in the southern hemisphere enjoy the beach and the sunshine – you lucky things, and spare a thought for us poor northerners who are stoking up the fire and closing all the windows tight to keep out the cold and the dark. This time I will leave you with a wonderful poem called The Praise of the Needle, thanks to Rebecca Devaney of Textile Tours of Paris for pointing it out to me. It was written by John Taylor and published in London in 1631, complete with brass engravings. You can find the complete poem online and it goes on for pages and pages – so here’s an extract:

To all dispersed sorts of Arts and Trades,

I write the Needles praise (that never fades)

So long as Children shall be got, or borne,

So long as Garments shall be made, or worne,

So long as Hemp or Flax, or Sheepe shall beare

Their linnen-woollen fleeces yeare by yeare;

So long as Silk-worms, with exhausted spoyle

Of their owne Entrailes, for mans gaine shall toyle:

Yea, till the World be quite dissolv’d and past;

So long at least, the Needles use shall last,

And though from Earth, his being did begin,

Yet through the fire he did his honour win:

And unto those that doe his service lacke,

Hee’s true as steele, and mettle to the backe.