The Refugees Who Dazzled London

Episode #28

This episode of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles tracks the story of the Huguenots, who they were, and why a summer wedding in Paris, four hundred and fifty years ago this August, ignited a violent massacre that forced them to flee France. It looks at some of the striking parallels between today’s Ukrainian refugees and the arrival of the Huguenots in Britain as refugees. It also thinks about the astonishing silk cloth the Huguenots were able to create on draw looms, working entirely without power in London weaving lofts, cloth that was designed to shimmer in candlelight and delight the Royal Court.

The people you can hear in this episode are:

Tessa Murdoch, who can be found on Instagram: @tessavioletmurdoch. Tessa has just published a new book on the crafts that the Huguenot families excelled in. It is called Europe Divided: Huguenot Refugee Art and Culture and it can be found in the Haptic and Hue UK bookshop and the US Bookshop.

Mary Schoeser is an acknowledged textile expert and co-founder of the School of Textiles in North Essex, UK. The School of Textiles issues a wonderfully informative newsletter which you can sign up for via their website. It also holds highly recommended study days and courses. The next event coming up is on Thursday, April 28th and it is on Sanderson Textiles. There are a few places left. You can find out more here. The School of Textiles is on Instagram as @schooloftextiles.

Mary is the author of several authoritative books on textiles, including World Textiles, which you can find in the UK Bookshop and the US Bookshop. And Textiles: The Art of Mankind, which is also in both bookshops.

Barra Little is Chairman of The Spitalfields Trust – which is a building preservation trust that campaigns for the historic environment. They have done a good deal of work in East London but also now work beyond that area and take on other projects as well.

The Victoria and Albert Museum holds many pattern books and original designs for Spitalfields silk. Their book called Spitalfields Silks, by Moira Thunder, is a good and relatively inexpensive place to start learning about these wonderful textiles. UK Bookshop/ US Bookshop

Many countries – as Tessa says in the podcast – have Huguenot resource centres. In the UK the Huguenot Museum in Rochester in Kent has been closed because of COVID, but they hope to re-open again shortly. If you want to find out more about your own Huguenot family that is an excellent place to start.

Kate Mosse, the author, has written two fiction books in a series about the Huguenots. The first is called The Burning Chambers in the UK and the US, and the second is called City of Tears, and so far, I can only find it in the UK.

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Spitalfields, London

Weaving Lofts, Spitalfields London

Barra Little, Chair of Spitalfields Trust

Spitalfields Weaving Lofts Seen From The Street.

Jamme Masjid Mosque, formerly a Huguenot church

Weaver’s House

Tessa Murdoch

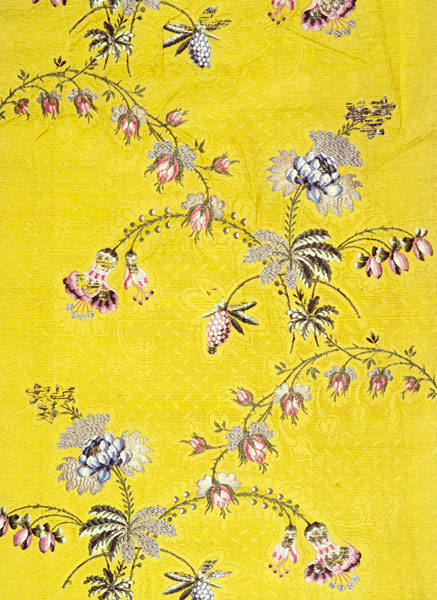

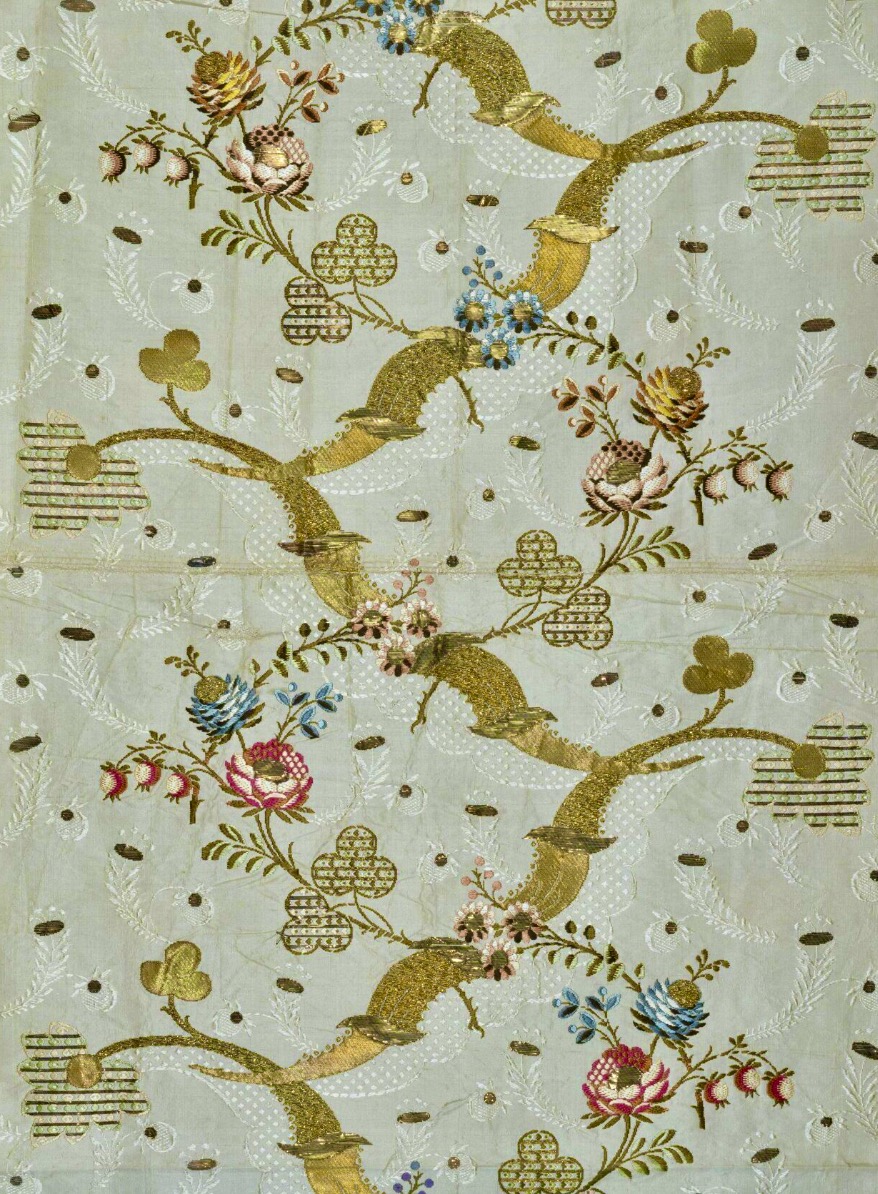

Spitalfields Silk, image courtesy of the V&A Museum, James Leman Design

Spitalfields Silk, image courtesy V&A Museum.

Spitalfields Silk, Image courtesy V &A Museum

Spitalfields Silk, Image courtesy V&A Museum

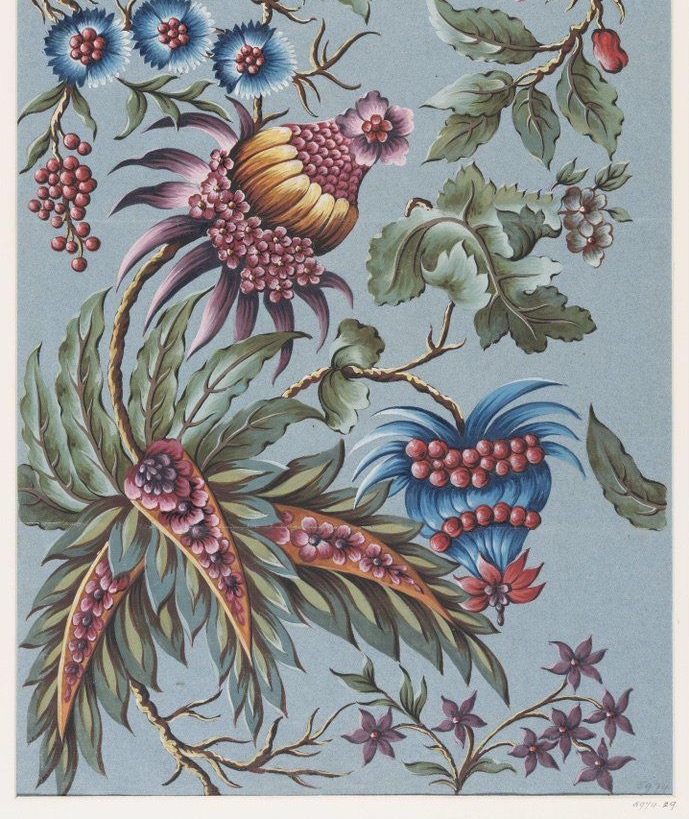

Design by Anna Maria Garthwaite. Image Courtesy V&A Museum.

Mary Schoeser, Co-Founder of the School of Textiles

Image Courtesy V&A Museum

Anna Maria Garthwaite Design, Image Courtesy V&A.

The Refugees Who Dazzled London

Welcome to Haptic and Hue and the start of a new season of podcasts, this time called Threads of Survival. My name is Jo Andrews, and I’m a handweaver interested in what cloth tells us about ourselves. I’m standing in the middle of London on the edge of the city’s financial district in an area called Spitalfields on the corner of Brick Lane and Fournier Street in front of a very plain brick building. These days, it’s the Jamme Masjid mosque, but you can always peel back the layers of history in London. And we find that before it was a mosque, it was a synagogue serving the Jewish community that fled here from Russia and Eastern Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries. And then if you peel back another layer, we find that this was first built as a church in the 1700s by French Huguenots in Spitalfields. This community were skilled silk weavers, and they were the first people in the world to be called refugees.

The Huguenots and their craft shaped this area of London. It was because of these drawloom weavers that Spitalfields silk became a byword for elegance and fabulously patterned and intensely coloured silk cloth in the 18th and early 19th centuries. This was complex, well-designed fabric, that could hold its own against material produced in France or Italy and was coveted around the world by those who could afford it. Even today the mark of these weavers remains, anyone can wander through this area and see the beautiful houses the Huguenot weavers built themselves. If you look up, the weaving lofts sit perched at the top of these houses. Barra Little, Chair of the Spitalfields Trust lives in a silk merchant’s house with a view over the whole district:

So here, you’re standing on the roof of our house in a roof garden which overlooks Spitalfields to the east. You can see all of the rooftops of Spitalfields from here. This house is the tallest in the neighbourhood. So, we’re looking down on the weavers’ houses built in the 1720s and 1750s. To my left is a row of houses on Wilkes Street. All of which have weavers’ lofts at the top of the house. And across from us, you can see the rooftops of Fournier Street, which is a mix of early and later Georgian houses. There are mixes of houses which are very much in the shape they were in when the Huguenots left and houses, which have been changed over the years to accommodate new owners.

JA: It always amazes me. The looms are so heavy and they’re getting them right up to the top of these houses. But then I suppose there was absolutely no electricity or nothing like that. So they had to do it.

Barra: You had to be up at the top to get the light. You’re sitting here on a cold day, but with absolutely gorgeous sunshine. And you can see by vantage of being up here to catch the rays and extend your day. These houses in some ways are fragile, but they are built with enormous internal beams. And so they would’ve been well able to handle the weight of the loom at the top of the house.

But as much as they made a success of their lives in London – the Huguenot weavers weren’t in the city by choice. They were forced migrants and this episode is about how they became refugees and what they made of it. Their influence – not just on London and not just on cloth – has been profound – nearly half of all US presidents have Huguenot ancestry. In many ways, they stand for the best of what migration brings a society. And in current circumstances, this is so much more than the dry and forgotten history of centuries ago. There is something profound in the story of the Huguenots and there are many parallels that show us a light along the path in the anxious days in which we find ourselves, even when stories have dark beginnings – as this one does. 450 years ago this summer in 1572 – A wedding was held in France – the marriage of Henri of Navarre – a future King of France – to Margaret of Valois and it should have been a cause for celebration, but instead it triggered Catholic mob violence which resulted in the deaths of thousands of French protestants and their families across France. Known as the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, it set off the first wave of Protestant Huguenots fleeing to Amsterdam, Germany, Switzerland, and Britain. Tessa Murdoch, who has Huguenot ancestry herself, and published a book last year on Huguenot Refugee Art and Culture explains who they were:

They were French followers of the Protestant reformer theologian Jean Calvin whose dates are 1509 to 1564. The French Protestants came from all over France, but by the mid 16th century, they had established centres. I think the first Protestant community was at Meaux and pretty soon after Paris, the metropolis, where the first national Protestant Synod was held in 1559.

For more than 100 years the persecution in France ebbed and flowed until in 1685 the Catholic French king definitively outlawed Protestantism – setting off an appalling wave of murder and terror:

Well, interestingly, the persecution of the Huguenots builds up during the sixteen seventies. So, one of the most sort of vicious campaigns was the Dragonards, the billeting of soldiers on Protestant families who forced their hosts to convert, ate them out of house and home, and destroyed their furnishings. If caught attempting to leave France, Huguenot men were sentenced to a lifetime’s penal servitude as galley slaves. So again, this resonates with the whole development of awareness of slavery. And we had Huguenot slaves operating in the Mediterranean, in the back door of Europe, as it were, women would be imprisoned or confined in Catholic convents, but perhaps the worst aspect was that any children captured, were taken away from their parents and educated as Catholics in convents.

But despite the terrible dangers many of them did manage to flee:

They did escape and there are many remarkable family stories about the way in which children were concealed in baskets of fruit or wine barrels. And then there are sort of accurate diary descriptions of how for example, those families, I’m thinking particularly the Perigal family who came from Dieppe, how they managed to cross the English Channel at night. And of course, many of these families had relatives who’d already managed to escape, which obviously encouraged them to aim and achieve this really very difficult journey. And there were established links between many Huguenot merchants in Normandy for example, particularly Rouen, which was effectively the port of Paris, and London. So, these trading links were very important in helping Huguenot families to plan their journey effectively.

Jo: It’s very like what’s happening today in a sense of people trying to cross the Channel in small boats. Isn’t it?

Tessa: Very much so. And I mean, I think in the last year, 2021, 25,000, roughly, refugees cross the English Channel in that way, and it is believed that of the some 50,000, probably more Huguenot refugees that made their home in the British Isles from the late 17th century into the early 18th century, 25,000 settled in London, the British metropolis when the total population of London was about 600,000. So, it’s a considerable proportion of the local population.

These were the people who were first called Réfugié by the French, which translates into English as Refugee, and down the years has become our universal word for anyone who flees persecution. Not all Huguenots came to Britain and of those who did, not all came to London, many settled first in Canterbury, Dover, and other parts of Kent. But despite the difficulties and the numbers, in the 1600s there was an outpouring of support and sympathy for these refugees – public money was collected in Britain and Ireland to support them, and by and large they were welcomed by the Government and people.

Tessa: Well, surprisingly they were actually if you remember that Charles II before the restoration of the monarchy had spent years of exile on the continent in the low countries, and in France, he was in terms of taste and aspiration a great Francophile. And so he issued an Edict of Welcome in 1681, enabling Huguenots to bring in their stock in trade and tools duty-free. In addition, there were house-to-house collections, and the royally endorsed Royal Bounty provided grants for those most in need that was administered by an English and French committee through the original French Protestant church, the Threadneedle Street church in the heart of the City. So, they were welcomed, yet the many hundreds of craftsmen who settled here were able to demonstrate a higher level of skill and formal training, than the native equivalence. And there were petitions from English Freeman members of the City Guilds, discouraging, the admission of, they were described as necessitous strangers, but interestingly, the Goldsmith Guild that I know well, I’m happy to be a Freeman of, recognized the advantage of these foreign craftsmen, that their high level of skill would encourage the development of the native skill. So, they turned a blind eye eventually. And, I suppose by 1710, there were some 30 Huguenot goldsmith masters accepted by the Goldsmiths Company. That’s one specific example.

Mary Schoeser, Co-Founder of the School of Textiles in North Essex in Britain and a renowned expert on Spitalfields silk draws a strong parallel between the reaction to the Huguenots and to Ukrainian refugees today.

Mary: Really what is it within humans that creates a sort of invisible bond? It’s a shared view of life. It’s a shared list of priorities. And so, for the weavers, it was independence. You know, a control of their own timing, weavers were, were self-employed and they got paid by the piece rate and whatever. So that meant, they were very proud of the fact that they had control of their working life. And they had control of their apprentices and their journeymen, et cetera, they were known to be well-read educated. So what have we got there? We’ve got independence. We’ve got a sense of self-determination. And we’ve got pride skill, real skills you know, hard work belief in hard work. Now that’s not too far a cry from what I think many people today feel deeply is something that we also see in the Ukraine. There is pride, there is hard work in this case against a terrible situation. There is a shared sense of the right way to do things. It’s less of a political alliance and more of a philosophical alliance that human beings have the right to determine their future and that those who work hard succeed.

The Huguenots tended to be skilled people – as well as weavers they were lace makers, goldsmiths, upholsterers, clock and watchmakers. And their workmanship was excellent, they were well trained in the French guild system and they were used to the demands of the stylish French court: here’s Mary:

Mary: The Huguenots had the clientele of the Royal Court. The French Court and Louis the 14th in particular was very determined that his Court would appear in the latest fashions, many say so that he kept them without funds to raise an army against him. That might be conjecture, but there is some logic behind that. And so, they had the clientele and that’s always what counts in this story. It is the wealthiest, the royalty, and the aristocrats who support the work of those weavers, like the Huguenots, who are making the most elaborate cloths. There was silk weaving already in Britain from the 16th century, but not brocades and not the very thick oh, so scrunchy sort of class called Pas de Soies. So not the kind of things that essentially were requirements for attending the French Court. And so, they brought those skills with them and that’s really what made the difference in the way the trade in Spitalfields began.

And in weaving they transformed what Britain could produce and changed the nature of what was available to those who could afford it.

Mary: So what defines Spitalfields’ work is that they’re working with silk, and silk is the finest of fibres. So, you can really draw with silk on the loom and it has to be a drawloom. And the drawloom was what the Huguenots really had extreme experience with because of their work for the Court. So, what did they look like? Well, they changed in fashion of course through time, but extraordinary lace-like patterns, floral patterns, big hefty elaborate Baroque patterns before that, when we get into the middle of the 18th century the English do begin to develop a style that’s recognizably their own. That’s the Rococo style. And that’s the use of very accurate botanically, drawn light, little bouquets and sprigs and meanders of flowers and leaves. And so, the ground is left without much evident patterning, but when you look at it really closely, you can see this really skilled use of the fact that the drawloom can manoeuvre every thread and you see really subtle single coloured patterns, damask patterns, little textures, things like that. So, in a candle-lit room, these gowns with these lovely single coloured textured surfaces would have glistened as the cloth moved. So, they were enticing and you know, they demanded attention. And that of course is what makes them perfect for court and aristocratic occasions.

These fabrics took London, then Britain, and then America by storm. Everyone wanted it even in small pieces, enough for ribbons on your hat or a waistcoat, if you were a man. But to afford a whole dress in Spitalfields silk you had to have deep pockets, although you might get one second-hand.

Mary: Essentially, if you could get it, you would wear it. And there were markets, of course, you know, it was the pattern that was setting the fashion rather than the shape of the garment. And so, these were gifted by royalty and aristocrats. They were gifted either to, you know, cousins or a poor aunt or to their lady in waiting. And they often then went into the marketplace as second-hand gowns.

Mary says Spitalfields silk changed the way dresses were made. It was so expensive that no one wanted to cut into it but instead, the dress was constructed around the silk.

Mary: Actually starting from the 1680s when the Huguenots arrived the construction changes very little in that what they do is preserve entire lengths of cloth in the construction. There isn’t a lot of tailoring in that kind of cut. The cloth is about 21 inches wide, and you have lengths, as in the sack back, where it’s just big pleats at the neck, and then it flows down all the way to the floor. Now that means that what you’re doing is walking with your bank account on your back, because that silk still has a value. And so you can gift it generously, or you can take it, to a market, or you can have a discussion with your tailor or whatever. So they had several lives. And it’s the magnificent Natalie Rothstein, the scholar now no longer with us, who was able to establish that, because she’s the one who studied every extant design for a Spitalfields weave, and went round the world and could point to a garment that had a provenance of say, 1756 and say, no, no, that pattern was designed in 1734, and I can show you the design for it. You see? So, you know, that really amplified what we understand about the provenance, the lifespan of these cloths, because silk is long-lasting. It’s very expensive, but it has tremendous tensile strength. It’s stronger than steel. So as long as you are kind to it, it has a long life.

This community over generations achieved enormous success, often using mercers – cloth merchants as middlemen. Spitalfields acted as a magnet for other weavers of non-Huguenot descent who married into the families and continued the craft. It’s also because of the complexity of Spitalfields silk that we begin to see the first emergence of weave designers:

Mary: Centuries and centuries of tradition, and still to this day is that the weaver is the designer. But really what we’re talking about is a very subtle almost invisible expression of the coming of the industrial revolution. It’s about the division of labour, you get the development of the wealth of the master weavers and the mercers. And it’s the master weavers who purchase the designs, sometimes on behalf of the mercers, sometimes the mercers themselves purchase a design and put it to the master weaver that they’re working with. And then that design is translated. It has to go through a complex process of being drawn out onto spread paper. And then the loom has to be tied up in order to lift it as per the design. And that can take two weeks, three weeks, four weeks, five weeks. It depends on how complex the design is and that’s a specialist skill. And so those exercises, if you like, begin to separate out in the way that the industrial revolution does create skill-specific enterprises. And so, there’s an opportunity there.

One of the people who we know first took up that opportunity was a Huguenot weaver called James Leman

Mary: And he was apprenticed in Canterbury, but moved up to Spitalfields. Now the Canterbury tradition still in the late 17th century was of a designer weaver, and then we watch it moving. And, the reason we know about James Leman is that it’s his designs that survive. And we know that he wasn’t necessarily always weaving them himself. And then you get to Anna Maria Garthwaite who must have understood the loom because you can’t design, it’s not like designing for print, even today. Really you can’t design a complex weave without understanding the weave structure. But she then is if you like, the first freelance designer in Spitalfields and she moves to Spitalfields specifically to pursue that work.

Anna Maria Garthwaite was an extraordinary figure, born in 1688, the daughter of a Leicestershire vicar with no Huguenot heritage – She was drawn to Spitalfields with her widowed sister and defying every stereotype of the day earnt her living as an independent woman. She designed more than a thousand patterns, and was influential in creating a recognizably English style of silk design based on floral motifs and botanical drawings, and was clearly a shrewd businesswoman.

The Huguenots didn’t only deal in silk – they also had a profound impact on another yarn – Linen. Louis Crommelin – a Huguenot born in northern France to a family of flax growers, came to Northern Ireland in the late 1600s and with the support of the King and Queen instituted a system for processing and weaving linen as well training for local apprentices in how to produce high quality woven linen. He is regarded as the father of the Irish linen industry.

And they have had an impact around the world – here’s Tessa:

Tessa: The Huguenot Society published a roll of the Huguenots who settled in the United Kingdom, which lists 500 Huguenot names, but also illustrates coats of arms for the leading Huguenot families, including the Bosanquets, the Bouveries, the Cazenoves, the Champion Du Crespigny, Chevalier, DeBoulay, Ligonier, Lefroy, Luard, Majendie, Martineau, Papillon, Romilly, and Vilolle families. And if you want to find out more and whether your name is a Huguenot name, there are Huguenot museums today in Berlin, in Rochester, Kent, adjacent to the French Hospital, in Paris, the Society for the History of French Protestantism Library and Collection, in France, and in the USA at historic Huguenot Street, New Paltz, upstate New York, which claims to be the oldest continuously inhabited street in North America. And, of course, in South Africa, there’s a Huguenot museum in Franschoek. And there are Huguenot societies in Australia, in America, in France, and in Germany.

No fewer than 21 American Presidents have Huguenot ancestry including Joe Biden. Paul Revere of the famous midnight ride was a Boston goldsmith of Huguenot descent. Davy Crockett, Joan Crawford, Daphne du Maurier, Laurence Olivier, Simon Lebon, Charlize Theron, Henry Longfellow, Gustav Faberge, the dizzying list goes on and on of those with ancestors who survived the persecution of the Huguenots. Back in Spitalfields as soon as the railways came and weaving began the transition from craft to industry production, the Huguenots started to depart, although they did not leave weaving. They took their businesses out of London and set up thriving enterprises in places like Sudbury in Suffolk and Macclesfield in Cheshire, some of which have survived into this century. With their departure the noise of looms was heard no more and Spitalfields rapidly became a Victorian slum – although its days of textile production were not quite over: here’s Barra Little of the Spitalfields Trust:

Barra: So Spitalfields declined quite quickly and these houses became houses for multiple families crammed into these spaces and stayed that way. There were waves of migrants after the Huguenots moved out of Spitalfields. There was, in the 19th century, a big influx of Jewish migrants. And so, this neighbourhood, which had been really dominated by Huguenot residents, became almost entirely Jewish and that wave of migration in was followed by a wave of migration out of Spitalfields and another wave of Bangladeshi migrants in the 20th century. And these houses were, actually interestingly, returned to their original purpose in a sense, which was mixed residential and commercial. They were what you might describe as sweatshops. This room was full of weaving equipment to make t-shirts or the like when it was first restored.

And as the Bangladeshi community began to move out in the later 20th century, the old weavers’ houses faced a new challenge.

Barra:Well, there was the threat of demolition that started the focus on these houses. They were at that point, actually remarkably well preserved, but very much undervalued. And as the wave of migrants who were generally single workers filling these houses, became more successful, the houses again were starting to empty and they were under threat of demolition on Elder Street, which is just across the street. A row of houses was in the process of being destroyed when the Spitalfields Trust founders decided to squat the houses to prevent their destruction. That was really at the beginning of a wave of awareness of conservation in this country and managed to attract a lot of support because these areas right at the core of London had been effectively forgotten about. The trust was formed after the success of saving those two weavers’ houses and has gone on to save dozens of houses across Spitalfields, London and now beyond.

Today this is a thriving area filled with people who value the houses for their history. Sadly there are no longer any weavers here, but Barra Little points out that they live on in the buildings they shaped and formed for their needs:

Barra: Well, we started in Spitalfields and you see, as you learn the language of these houses, how weaving was really integral to the way they were built and used, and those skills have continued to be applied. I first was involved with the Trust because of some very small houses down in Whitechapel, which were entirely derelict, and were about to be torn down. The Trust stepped in to save those houses and added weaver’s lofts to the houses to make them now new family homes. So, we borrowed the language of the architecture from Spitalfields and applied them there. And those sorts of practical solutions to building is something that we really pride ourselves on. The reason we have weaver’s lofts at the top of these houses is so that people working on the looms could catch the last of the daylight. And of course, today it’s equally important to have spaces in which people can work and live catching the light. So, I think we carry with us the history of the interaction between weavers and these buildings.

The story of the Huguenots has something to tell us about refugees, whoever they are and where ever they come from. Few of those who flee persecution have an easy passage, especially today, when the world often seems tired of their plight. But as we look back at the Huguenots it allows us to ask the questions born of hope: can we see today’s refugees not just as victims, but ask as well what do they bring us and what will they contribute to our societies in the future?

There are some changes to Haptic and Hue this Season. Episodes will now be uploaded on the first Thursday of every month and will continue throughout the year with a short break in the summer. This is to give us a chance to explore more widely and to research some topics that we don’t know so well. But Haptic and Hue remains me, a handweaver with a microphone, Bill Taylor, the editor and producer with a laptop, and you – the fantastically supportive listeners who bring us ideas and support this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee. If you would like to help us you can find the coffee button on our website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen where you will also find pictures, more about the people you heard in this episode, background reading, and a full script. This time I’ll leave you with an extract from a poem called Home by the British Somali poet, Warsan Shire.

No one leaves home unless

home is the mouth of a shark.

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city

running as well.

your neighbours running faster

than you, the boy you went to school with

who kissed you dizzy behind

the old tin factory is

holding a gun bigger than his body,

you only leave home

when home won’t let you stay.

no one would leave home unless home

chased you, fire under feet,

hot blood in your belly.

it’s not something you ever thought about

doing, and so when you did –

you carried the anthem under your breath,

waiting until the airport toilet

to tear up the passport and swallow,

each mouthful of paper making it clear that

you would not be going back.

you have to understand,

no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land.

who would choose to spend days

and nights in the stomach of a truck

unless the miles travelled

meant something more than the journey.