Episode #62

Jo Andrews

In Denmark more than a hundred marsh bodies have been found – some in extraordinary states of preservation. They date from the late Bronze and early Iron Ages, and are between 1,500 and 3,000 years old. But what some of them are wearing can take us back much further than that, into a time when humans first started to cover their bodies with clothing. For this episode, Jo travelled to the National Museum of Denmark, in Copenhagen, to explore the textiles of two of the world’s most famous bog bodies.

Notes

The National Museum of Denmark is in Copenhagen and you can see both Huldremose woman and Egtved Girl and their clothing there. It is well worth the visit. Here is the website: https://nationalmuseet.dk/en and here are the pages about Huldremose Woman: https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-early-iron-age/the-woman-from-huldremose/ and Egtved Girl https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-bronze-age/the-egtved-girl/

You can find Ida Demant on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/idasybille/ and you can find Land of Legends at https://www.instagram.com/sagnlandetlejre/ and https://sagnlandet.dk/

Ulla Mannering with a reconstruction of Egtved Girl’s clothing at the National Museum of Denmark

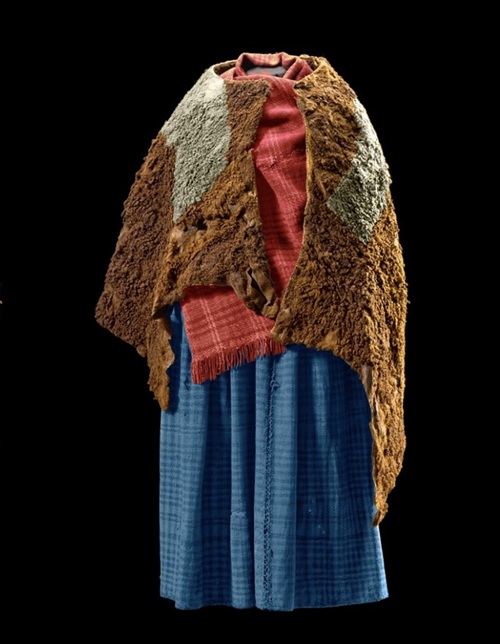

Reconstruction of Huldremose Woman’s clothing

What Huldremose Women’s clothing might have looked like

Huldremose Woman in the Museum

Egtved Girl’s oak coffin in the Museum

Typical bog landscape in Denmark: Photo Credit: Carsten Brandt I-Stock

How the reconstructed top and skirt fitted

Ida Demant at Sagnlandet Lejre: photo by Ole Malling

Ida recreating the string skirt: work in progress with assistance

Workshop at Sagnlandet Lejre

Dye workshop and textile workshop at Sagnlandet Lejre

Egtved Girl’s coffin and clothing in the Museum

Reconstruction of Egtved Girl’s Costume at the National Museum of Denmark

Venus of Lespugue from circa 23,000 BCE

Script

The Mysteries of the Marshes: Ancient Textile Secrets of Europe’s Bog Bodies

JA: On May 15th 1879 two Danish men were hard at work digging peat as fuel for fires in a remote area of north east Jutland called Huldremose. It was tough labour as they cut out the slabs of soft earth in long lines with wooden spades, working about two meters down from the surface when, suddenly, one of them struck something that didn’t feel like peat.

Ulla Mannering: And it must have been really a horrible experience for these people. I think they knew that there were bog bodies around, in the peat bogs, but they never knew when or where they would meet these finds. So, what happens is that they realize that, oh wow, there’s a body lying here. And they stopped working because they try sort of to uncover the body as much as they can, because she’s very well wrapped into the skin garments. And they think, oh, right, there was a man that disappeared here in this area, some 10, 15 years ago. Could it be him lying in the bog?

JA: That’s Ulla Mannering, Research Professor in Textile Archaeology at the National Museum of Denmark, and don’t worry, this hasn’t turned into a true crime podcast, it’s still very much Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles. Welcome back after the summer break, I’m Jo Andrews, a handweaver interested what textiles tell us about ourselves and our communities: stories that go far beyond the written word and explore the lives of those who had no part in great events and no voice in history but nonetheless have wonderful things to tell us. This is a story though that deals with bodies, ancient bodies, and if that is not for you, then listen no further. Back at the peat bog, as the workmen thought they had uncovered a recent murder they sent for the local policeman:

Ulla: And the policeman, he takes with him the doctor, next day they come to this bog and they take the body up and bring it to the nearest farm where they start to sort of unfolding and unravelling and cleaning the body. Quite fast, they realize, this is not a man, it must be a woman. And it’s not a modern corpse. It’s actually an ancient corpse. So of course, the policeman, he realizes that this is not a criminal case, <laugh. It’s a relief for him. He can go home. But the doctor, he has friends in Copenhagen. So, he knows that if it’s not a modern, then it’s probably an ancient, and then it is something that belongs to the National Museum. They carefully record when they unravel and take off actually the clothes of the woman. So, he knows that these are archaeological objects that, that the National Museum would like to probably have. So, they undress her and they bury the woman in the cemetery, in this local area. They take all her clothes off and bury her, because that’s what you would do with a body. Of course, they know she’s not a Christian, but still, I mean, it’s for courtesy. And you know what they would do with the body. You put her in a coffin and you bury her.

JA: So far so good, then the Doctor took all the clothing home. What happened next says a great deal for Iron Age clothing, and it also tells us a lot about the values of a 19th century Danish Doctor’s wife.

Ulla: And when he gets home, his wife washes all the clothing because they were not, I mean, in a peat bog, it’s not soil, it’s, it is peat, it’s plant remains. But there must have been a lot of plant remains to grow into and around these textiles. So, they must have been dirty looking, but it would not be soil like in a grave, in a sense. But, so she washes things and hangs up and, and it dries. It survives this quite nicely.

JA: Her name was Mrs Steenberg and although she didn’t know it, what she washed on that spring day in 1879, was some of the best-preserved and most complete iron age clothing we have. Huldremose Woman, as she became known, was buried for the first time in the bog around two thousand years ago. She was wearing a long plaid skirt – something I would be happy to wear myself today – it was dyed in blue tones, she also had a red scarf or wrap and over that two lambskin capes. As the washing was hung out to dry, Dr Steenberg telegraphed the National Museum:

Ulla: Very fast, when the Museum get this this news, they reply, oh, thank you very much that we would like, but we would also like to have the body. So now they are in trouble, <laugh>, because they don’t have the body, so they have to go back to the church and dig up the body, I suppose they put her in a coffin. So, she was probably a wooden coffin, very simple one, but she was probably fairly easy to dig up again. And he then brings the body back to the to the medical house where she is in store. He has to pay for the shipment of all the objects. And now it’s not just objects, it’s also a dead body. And that’s not so nice. He tries to negotiate a good price by steamboat. It sails from Grenaa to Copenhagen. And the Museum then receives all of it. They are very happy.

JA: Huldremose Woman was now at the Museum, and she should have been safe. But sadly, not. Her clothing was immediately put on display, but her body was stored, un-regarded, in the basement for years, before going missing. She was lost in an unlabelled box for more than seventy years, and only found by chance. It was only in 2008 that the Museum decided to reunite her with her clothing and to show her just as she was found. And it is an extraordinary thing to stand right beside this gently curled woman, fully dressed in her clothing in the dim lighting of the Museum, as Ulla and I did, and think how like us she is and yet how far from us:

Ulla: She’s very recognizable as a human. And of course, it’s in a way it’s I think it’s very touching to be able to face a prehistoric person like that. Some people think it’s scary. And I I understand that it can be a strong experience, but I think that I think it’s also very interesting to actually to see a prehistoric person and to recognize that they are just like us <laugh>. And that’s, I think that’s the beauty. It’s such a different and much more direct experience. I think that the bog bodies with their clothing, they speak directly to you. When a lot of people come into this room, they say, they look at it and say this, this can’t be 2000 years old, but it is 2000 years old. And I think just for people to realize that here you actually look at something, which in a way looks very, very modern and something that you can relate to. You can see the textiles, you can see that they have colours and, and patterns, and you can almost feel the nice texture of the skin colour. But it gives you this very direct and tactile experience of something, which to a lot of people is extremely difficult to grasp. What would prehistoric life be? How did they live? What did they see? But I think when we see a body like this with textiles that are in a way, very modern, and something which we just, with our tacit knowledge, actually do understand, that this could either be pleasant or unpleasant or warm or cold. And why has she got bare feet? And so, I think actually it brings up a lot of new questions for the Museum’s spectators that with a lot of words, it’s extremely difficult to explain to people about prehistoric life.

JA: To understand more about how Huldremose woman and other Iron Age people across Europe lived we need to know more about how they understood the bog. By this time in Denmark most of the trees had gone – it had become a society of small farms and these homesteads were built close to bogs, which Ulla says had a special meaning for them:

Ulla: It has probably been a very mysterious place. There is often a fog over the land because the water you know gives this temperature difference. And, so you get this foggy area. it could be that this is an area which is a place where they thought they had an easier access to their ancestors and to the gods. But it’s just next to their fields. It’s just next to the farm. So, it’s not something you have to walk for hours in order to use it. It’s just down the hill. There’s the bog, and we use it for peat, for heat. We use it as a, maybe a refrigerator, because the nice thing about a bog is that it’s almost all year round the same temperature. So actually, we know that they could store things that should have a cooler temperature, for instance, like butter, so it’s also in a way a refrigerator. And we know for later periods that when they start sailing long distances, they often took water from the bog because it lasted fresh for a longer period because probably of the slight acidic water content that came from the peat itself. So, they knew a lot about all the good things that they could get from the bog. And it was a very diverse resource area and very important in their agricultural every day.

JA: In Ireland they have found large lumps of bog butter more than 2,000 years old still in a recognisable condition. So, the bog was both an enormously practical place and also a thin, liminal place where ancestors and gods were probably easier to contact. Ulla says sometimes they find vessels with sacrifices of food in the marshes. But even so it was not the most common way to bury people in the Iron Age.

Ulla: Because at this time, you would be cremated and placed in a communal cemetery or graveyard and your things would be placed maybe where you had this, the fire, the cremation, and then covered with a small mound. And you would have these small communal grave areas that were probably belonging to several families or one family in this local area. So, something completely different happened to the bog bodies. They were not cremated, they were buried as full body in clothing. And so, this is an unusual way of treating the body. So obviously they are not part of the most common burial ritual in this period.

JA: We know that Huldremose women was around 40 when she died, at the end of her life span for the Iron Age, and at a time when clothing was time consuming to make.

Ulla: She was very brightly dressed. Yes. She is wearing two skin capes, sheep skin capes which have also multiple natural colours. The textiles are also made by sheep wool, and they are made in checks and stripes. So, what they did, they sorted the wool into different colours. Then they spun the yarn in these natural pigmented colours, and then they wove the textiles in checks and stripes. So, they had these really fancy patterns.

JA: Each of the capes would have taken the skins of four lambs, so at least eight sheep were killed for them. All her woven clothing was made on the simple but well established two beam loom, which by this time would already have been in use for many hundreds of years. But the dye colours have a great deal to tell about how fabric was used two thousand years ago.

Ulla: And then at the second stage, they started dyeing the items. And in a few cases, we have been able to prove that they dyed the yarn, but in most cases, it looks as if they dyed actually the finished textiles. And the most common colours are yellow. In a few cases we have blue, blue colours, and very rarely red. But the Huldremose woman is really exceptional <laugh> also because the scarf has yellow but also a red plant dye. And at some stage, also a blue.

JA: What seems to be happening is that rather than doing what we do, which go out and buy a new outfit, these people used different dye pots down the years to give a new look to their old garments, changing the colours and, if you like, upcycling or refreshing them.

Ulla So probably what we see is that the, the colours were not stable and that they had to re-dye at certain stages. They re-dye. And in that process, they changed the colours. And what we see is the whole sort of range of repeated colour changes in a textile’s lifetime. And these textiles, they are so well made that they could easily have been worn for 20, 30 years., so they would have a long lifetime of use.

JA: Huldremose Woman was also wearing a linen shift under her bright woollen clothing. However, linen isn’t preserved in the acid conditions of a bog, and nothing remains of it beyond a few tiny traces. What the textiles tell us though is that this woman was a respected member of a community, one that had of a great deal of useful cultural knowledge and access to resources. She couldn’t read or write, she wasn’t a great leader, but it infuriates Ulla that Huldremose Woman and the other bog people have been dismissed as of no importance:

Ulla: For many years people said, ah, but the bog bodies, they are poor people because they have no metal objects. There are no grave goods with these people. They were not recognized as rich people, in their society. And I say, these people were very, very rich because they had access to all the most important resources, clothing, and it was well-made clothing, with colours and all the details that showed that they were part of this community and had access to the resources and the knowledge in order to produce all of these fantastic clothing items. There were no textile shops in the Iron Age. You were producing all your raw materials on your farm, and if you were good farmer, you had good resources, you had good products that you could eventually make into clothing items. And we can see from the textile technology that it used an enormous amount of time in order to produce these textiles.

JA: So, she was wealthy, but that wealth wasn’t expressed in coin – and this has been a constant problem for textile archaeologist to get their colleagues to understand that although stone, metal and bone survive longer, they only give you part of the story – textiles hold the other half. They matter, especially in a society where if your harvest failed, you starved, if your sheep were badly fed, you had no wool. These resources were precious: so does this mean we can say this woman was loved?

Ulla: And to me, it shows that she was a cherished person. They could have stripped her of all the clothing, but they didn’t, they placed her in the bog with so many valuable objects that it must have been a really a big sacrifice for the living to give all of this. So, we have no idea whether these are personal belongings or are part of communal ownership. And she was 40 years when she died, so she was a quite an old woman. So she must have had a lot of experience and personal knowledge that was also important in this society, When you look at the textiles, she represents a care that is actually difficult for us to understand today. Because textiles are not our primary value way of giving value to things, but in this society, they were really, really important.

JA: But in Denmark textiles can take us much further back than this. In another room at the Museum, not far from Huldremose Woman, lie the remains of Egtved Girl. She’s wearing wool clothing that was made nearly three and a half thousand years ago. Old enough you may think in itself, but the design of her skirt points even further back, deep into pre-history to the very beginnings of human fascination with clothing. First though we have to deal with the values of the early 20th century, and what happened when Egtved Girl was first found. Here’s Ulla;

Ulla: She was excavated in a time in 1921 when of course archaeology was very important and also a political tool. And when they found this coffin with the textiles preserved inside, they brought the coffin without touching it too much straight to Copenhagen. And it was excavated here and recorded.

JA: There was a great deal of excited public attention as the solid oak coffin was opened and the public prepared to see what they thought would be a perfect flower of early Danish womanhood.

Ulla: But what was really the big issue was that she was wearing this corded skirt, and it’s this short skirt. It’s only 38 centimetres long. So, it’s really, it is short and it’s, made of, out of more than 300 cords. When it just hangs on the body, it looks solid. But as soon as you start moving, you can see everything underneath it. Your legs and your pelvis will be visible. And in 1921, clothing was starting to get shorter, but this length of clothing would be, I mean, out of the question for any woman, you might be able to show your ankles, but not anything above the knee. And so, in 1921, they had this idea of our glorious past and, and women in prehistory. And then actually being so exposed and not honourably dressed. people had really difficulties understanding that you could be in a way so naked and still be, an honourable woman dressed and placed in a grave with a lot of prestigious grave goods and all of this. So, this idea of the honourable woman and high status simply clashed, in society in 1921 caused a scandal. I think it caused a scandal.

JA: Debate has raged ever since about who Egtved Girl was and why she wasn’t dressed as an allegedly “civilised person”. But this probably says more about us than it does about her. We know she was between 16 and 18 when she died. As well as her corded skirt, she was buried with a big bronze plate fixed around her waist, a woven woollen top and she had a large folded blanket in the grave. So good is scientific dating now that from the oak coffin and the flowers placed in it, we know she was buried on a summer’s day in 1370 BCE. We also know that her skirt was not unique, there have been other finds of partial preserved corded skirts:

Ulla: So, it was an important part of female clothing. And we even have some small bronze figurines showing females in these very, very short corded skirts. That of course, has led to the idea that maybe it’s a kind of clothing that you wear in rituals and in combination with the dancers or ritual feast or whatever that she could have been or priestesses. But I think this is an everyday costume. I don’t think that we should sort of move her into a completely very sacred sphere, but just see this as something you could wear in the Bronze Age. And, many women were wearing these types of corded skirts.

JA: Ulla thinks these kind of skirts – corded skirts – may date back thousands of years further.

Ulla: Actually, the corded skirt is the most ancient clothing item we have from mankind. So, it’s probably an idea of making a clothing item that relates back to the Stone Age, and the earliest times you could easily do this, in a skin, or you could do it in a plant fibre or plant remains, and actually, we found there are corded skirts in many cultures all over the world. And I think, this goes back to the one of the earliest ideas probably of, of how to cover your body.

JA: The earliest known works of figurative art that we have in the world are the so-called Venus figures that date back to thirty thousand years ago. These are exaggerated female forms and have often been interpreted as fertility icons. Some of them – like the Venus of Lespuge from France, seem to be wearing corded skirts. If Egtved’s Girl’s skirt is their descendant then we can say that this kind of garment is something that has persisted for tens of thousands of years as a piece of clothing and seems to have been made all over in many different materials:

Ida Demant: I like the idea <laugh>. Let’s put it like that. I like the idea of it being part of a very old, idea or very old design.

JA: Ida Demant is an archaeologist who specialises in prehistoric textiles.

Ida: And I’m based at this place called Sagenlandet Lejre, they also call it Land of Legends in English. And there we have this textile workshop where we do weaving and spinning and dyeing, plant dyeing. And we work with reconstructions of ancient textiles and archaeological textiles, historical textiles.

JA: Ida has recreated the skirt herself in wool, it’s complex and time consuming to do – it took her around a month to weave it and twist the cords, and she says she is still struggling with idea of how it would have been made before the arrival of sheep’s wool:

Ida: But I think the idea of some kind of corded skirt as an ancient old design, I can easily believe that, just made in other materials and wool. And that’s this idea that’s been passed down and, and then transferred to wool because the twisting of the cords is reminds me of rope technology. So that’s why I totally like the idea.

JA: But for the moment Ida thinks we lack the conclusive evidence that this actually happened, as so far, no string skirt made from plant material has been found. Recreating a garment like Egtved’s Girls skirt is enormously valuable because it gives us a lot of new information about the thinking behind it:

Ida: How would they have set the whole thing up? As I see it, the skirt is a band weaving where you extend the threads out as long loops to one side. You pull them through as loops, and then you extend them out. And these loops you twist and they become the cords of the corded skirt of the Egtved girl or the Bronze Age skirts. And how they would set that band up. I’ve been thinking about a lot <laugh>. And, and how would they would’ve been sitting on the ground? Or would they have put it up on a loom in upright or horizontally? How would they have done that and what would be the most efficient and most practical from their point of view?

JA: Ida thinks the making of the skirt itself was the work of one pair of hands.

Ida: I think this is one-person thing. No, not spinning. Spinning. The yarn would’ve been a community thing could easily be, because that would’ve been the most time-consuming part that is always spinning the yarn. That could have been a community thing, but the actual weaving and twisting of the yarn, I think would be enough for one person.

JA: And so gradually from the textiles, we can reach back and build a picture of this community nearly three and half thousand years ago working together to spin the yarn and then passing it on to one person with the skills to create a skirt that held meaning and significance for them. They followed a design that seems to have come down thousands of years, passed by word of mouth from generation to generation. But they were working with a material that wasn’t that familiar to them. Wool was relatively new to Denmark and we can see this in the simple blouse that the Egtved girl was wearing, and another two from the same era that have been found: all of them are designed in the same odd way:

Ida: If you are looking at these tops and the way they are cut and made, they indicate that they were originally designed for a much smaller material of a more limited size. All three of them are extended at the bottom with an extra piece. And if you were only doing that in woven fabric, you wouldn’t need to do that. But because it, let’s say skin, any of some kind of animal skin was the original use for this design, then you would have to add more bits to it to make it long enough. But you continue doing that because that’s how you do, because the design in itself, I don’t think it’s suitable for woven fabrics the way you, you have no seam allowances. That’s, it’s very difficult to make proper seam allowances in the way it’s put together in, in it’s sewn together. So, I think it was originally designed for skin and these little extensions, they prove that, if we may say, <laugh>, but they continue to use them because that’s how they do.

Jo: Because they think that’s the right way.

Ida: That’s the right way.

JA: It took time for them to work out that they didn’t need these extra flaps when they were weaving with wool. But it took time to adjust to the new material. I love the fact that by looking at the the way textiles were constructed we begin to get an insight in people’s though processes all those years ago. Ida says she’s not a romantic person and she feels more of a connection to the textile rather than the person, but there is an exception to that:

Ida: Where I feel the sense of the person that’s actually where they make the mistakes. That’s where I feel the person behind it, the people behind it. Where they make the solutions, where you can see they’ve been thinking or not thinking, instead of where it’s just the repetitiveness of it. I always get more fascinated when they make a mistake or you can see they have thought out some clever solution to something. That’s where I feel the connection to the person who made the things.

JA: She says that Egtved girl’s string skirt was clearly mended.

Ida: The original is worn and they made repairs. I’m not recreating as such the repairs, but I can see the repairs. The end bit, that’s used to tie the skirt around the body. It’s been repaired it’s been worn out, out at the top. And then they just stitch some coarse stitches around this selvedge. That’s, that’s a repair, that’s where you can see. And you, I think the end of it has been much more elaborate than we can see today. But again, they’re just tied a knot. That’s something to prevent it from dissolving even more <laugh> falling into pieces. That’s where I can see the people in it. That’s where you can see, oh, this has actually been used. It’s not been made for display, just for putting in a grave. It’s actually been used by someone. It’s been used over a long time, so it’s been worn and they’ve done something to stop the wear, so, it can continue in use.

JA: We can’t go back thousands of years to see exactly who our ancestors were, but understanding their textiles and their designs, seeing their mends and mistakes allows us to follow their thoughts, and it makes their hands visible to us all these centuries later. Here’s Ulla:

Ulla: To dig into the world of archaeological textiles and especially Bronze age or early Iron Age textiles is absolutely fascinating. The care and the knowledge they had about the resources and how they transformed all of these resources into something so beautiful and useful and valuable, I think that’s amazing. We have a very superficial attitude towards our clothing and the way we use our resources today. We don’t think about all the hands that our clothing item has passed through until they get into the shops. We never think about where are the materials coming from, who knew how to herd the sheep, pluck the wool, to sort the wool into different qualities, to spin it into a yarn, to weave it into a fabric, to dye it with plants that they had collected in the environment or cultivated. Because they knew they had this specific land they knew could give red, or this plant could give a yellow or a blue colour. I think that that teaches us in a way that we have to be much more careful and aware of the value of things.

JA: For Ulla it is the textiles, and seeing the craft and skill of the Bronze and Iron Age people that she enjoys.

Ulla: And I think that these people, they knew very well was what was important. And the joy, the mere joy for me as a textile researcher, just to look at these textiles and see how they were constantly striving to improve techniques and visual appearance, to me that’s astonishing. And it gives me sort of a personal pleasure and, and joy that we are actually able to understand these people from their craft. I think that’s really important. If we didn’t have the craft and the things, the products that they used so much time in order to produce. I think it would be really difficult for us to relate to our, maybe not direct ancestors, but at least the people that inhabited, were living, in these areas before us.

JA: Thank you for listening, and thank you to Ulla and Ida for their enormously thoughtful input to this episode about how Bronze Age and Iron people thought and made. If you would like to see pictures of Huldremose Woman and Egtved Girl and their clothing, then head over to www.hapticandhue.com/listen and look for Series Seven.

Haptic and Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews. It is edited and produced by Bill Taylor and sound edited by Charles Lomas of Darkroom Productions. It is an independent podcast free of ads and sponsorship, supported entirely by its listeners, who generously fund us through Buy Me a Coffee or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. Friends get access to free textile gifts every month and an extra podcast hosted by me and Bill Taylor, where we cover interesting events and the textile news of the day. To join Friends, go to www.hapticandhue.com/join. In the next edition of Friends, we will be talking to Nicole de Ruchie who has just published a book called yes – Bog Fashion – all about how to make your own Bronze and Iron Age clothing.

We will also be back next month with a look at what stitching and textile crafts do to your brain – not your bank balance – your brain! But until then its good bye from me and enjoy whatever you are making.