Episode #55

Jo Andrews

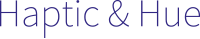

The Bayeux Tapestry was created by women in an age of great violence and uncertainty. It became the defining narrative of the battle between Harold Godwinson and William, Duke of Normandy, for the throne of England that took place in 1066.

The Great Tapestry of Scotland – finished just over ten years ago is an incredible work that retells the story of an entire nation from its very beginnings. It shows that when women tell the story in stitches a very different kind of history emerges.

Neither work changes the facts – nothing does that – but both are demonstrations of the power of stitch to re-define how we see ourselves and give us different perspectives on events, which ones we find important and what we feel about them. This episode of Haptic & Hue is about the power of stitch, ancient and modern, to frame and reframe our stories.

Notes:

More about the Bayeux Tapestry can be found at https://www.bayeuxmuseum.com/en/the-bayeux-tapestry/

And more about the Great Tapestry of Scotland at https://www.greattapestryofscotland.com/

Michael Lewis and David Musgrove’s book is called The Story of the Bayeux Tapestry and it can be found in the Haptic and Hue UK Bookshop and the Haptic & Hue US Bookshop

Michael Lewis is a member of the Bayeux Tapestry Scientific Committee (2013 to present), advising Bayeux Museum on the redisplay and reinterpretation of the embroidery. He is also head of the British Museum’s Portable Antiquities Scheme, established to record archaeological finds discovered by the public in England and Wales. He can also be found on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/tostig1066lewis/

Friends of Haptic & Hue have adopted Bayeux Stitch at the Royal School of Needlework’s Stitchbank and if you would like to find out more about the stitch or even try to re-create it for yourself here is the link: https://rsnstitchbank.org/stitch/bayeux-stitch

Clare Hunter’s books are Threads of Life and Embroidering Her Truth, about Mary Queen of Scots. Clare was interviewed about Embroidering Her Truth on Haptic and Hue when it came out, in the Episode called Stitches by Candlelight. https://hapticandhue.com/mary-queen-of-scots/ Clare is also on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/sewingmatters/

Alistair Moffat is the author of many books about Scotland and its history. You can find his website at https://alistairmoffat.wordpress.com/ and his many books in most good bookshops. He has just published a new book about the making of The Great Tapestry of Scotland, which is in the UK Haptic and Hue Bookshop and the US Haptic and Hue Bookshop. It has a picture of every panel.

Dorie Wilkie is on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/doriewilkie/ and is the collator of a wonderful book Sharing Yarns which records the Stitchers’ experience of making their panels.

Professor Michael Lewis

Bayeux Tapestry

Bayeux Tapestry

Clare Hunter

Bayeux Tapestry

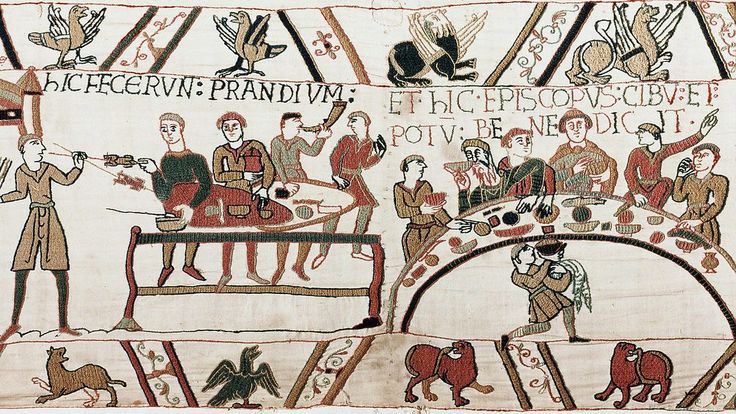

Horses showing Bayeux Stitch

Shetland Knitters Great Tapestry of Scotland

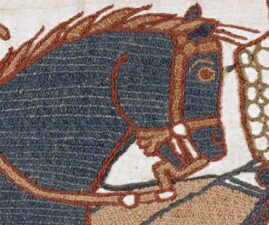

Harris Tweed Weaver Great Tapestry of Scotland

Alistair Moffat

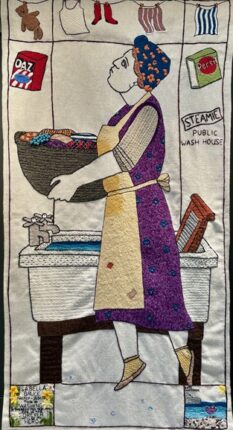

Washerwomen Great Tapestry of Scotland

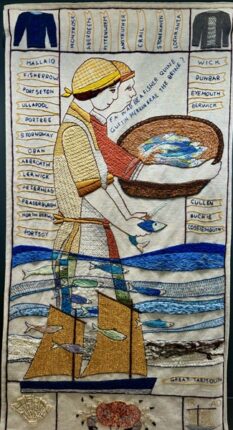

Fisher Lassies Great Tapestry of Scotland

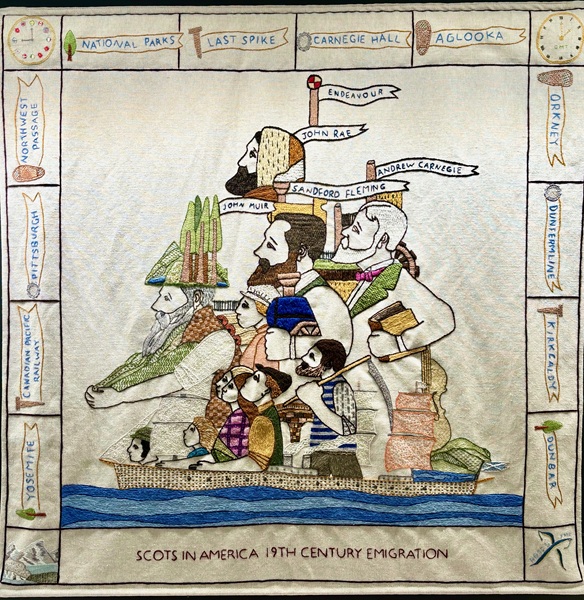

Scots in America. Great Tapestry of Scotland

Jo Andrews and Head Stitcher Dorie Wilkie

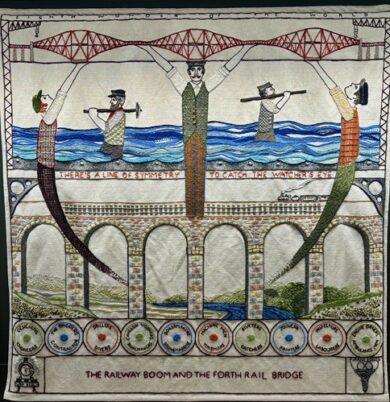

Building the Forth Road Bridge Great Tapestry of Scotland

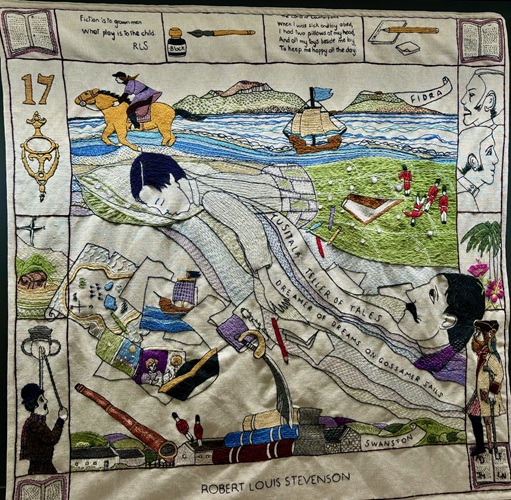

Robert Louis Stevenson Great Tapestry of Scotland

Script

Tapestries for Troubled Times

JA: Nearly a thousand years ago a group of women were gathered together to stitch the story of the Norman Conquest of England. Almost everyone knows the work of art they made over years of labour. The Bayeux Tapestry is recognised by UNESCO as a Memory of the World and it has come to define, in stitch, an age and a story. It survives, miraculously, to this day in Northern France in the little town of Bayeux, and is rightly celebrated. But few think about the Anglo-Saxon women who made it – women who came from the families of the defeated – and the desperate age of change and deep uncertainty that they faced.

Michael: We’ve got a group of women essentially that are coming together that might have had quite individual experiences of the Norman Conquest. And those experiences might be quite varied maybe their husbands even got killed in the Battle of Hastings or their sons or other people. And they would be reflecting upon that, I guess, as they were creating this work of art. I think they would’ve had quite interesting conversations, whether it helped them make sense of it, I don’t really know, but it certainly would probably trigger quite a lot of different emotions, I would’ve thought, wouldn’t it? And you know, maybe there was an element where speaking to other people was, was helpful to a degree as well. But I guess that a lot of them would’ve had a similar sort of experience of the Norman Conquest, what had happened to their families, and then maybe their kind of fears or hopes for what the future might bring.

JA: Michael Lewis is a member of the Bayeux Tapestry Scientific Committee and co-author with David Musgrove of a recent book on the Tapestry. I’m Jo Andrews the host of Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles and this episode – the first of Season Seven – is about the power of stitch to define our histories and to tell and re-tell our stories, particularly in ages of profound change and uncertainty.

As many know the Bayeux Tapestry is not a tapestry at all but an embroidery – it got stuck with its name by a French monk called Bernard de Montfaucon in 1729 when he published engravings of the work and called it a Tapisserie: sadly it stuck and ever since it’s been the Bayeux Tapestry, even though it’s unlikely to have been made in Bayeux. The more or less settled thinking is that it was commissioned by Bishop Odo, half-brother to the victor of the Battle of Hastings, William, Duke of Normandy, the new King of England. Odo was both Bishop of Bayeux and the newly created Duke of Kent. The thought is that the tapestry was stitched in or close to Canterbury in Kent.

Michael: It seems that the Bayeux tapestry designers have been influenced by Canterbury produced manuscript art, or at least manuscript art that was in Canterbury. And so there’s a suggestion, which I believe that the Tapestry designer had access to the libraries of both St. Augustine’s and Christchurch at Canterbury or manuscripts based in those. Now, there is another problem with that in that <laugh> in that Canterbury is probably one of the best preserved archives in terms of the books produced there. So maybe we have a bias in the information that leads us to, to go to Canterbury, but nonetheless, there’s a couple of scenes within the Bayeux Tapestry that almost seem to be directly borrowed from Canterbury manuscripts.

JA: We will never know exactly who the stitchers were or what they thought, but the tapestry they made allows us imaginatively to reach back to them and the age they lived in. The tapestry is stitched on linen and worked in wool dyed with plants. A lot of scholars thought it might have been created by nuns, but Michael Lewis says that at the time embroidery skills were far more widespread.

Michael: But when you look at the historical sources that talk about embroiderers and people doing this sort of work in the late Anglo-Saxon period into the Anglo-Norman period, they talk a lot about aristocratic women, not to say that aristocratic women made the Bayeux Tapestry, but they were certainly doing embroidery and other sorts of textile works. But they also talk about people you know, on an everyday basis, producing garments and materials. And if you look at late Anglo-Saxon society, that makes a lot of sense, doesn’t it, really, that people are making their own clothes. They would probably learn a lot of the techniques that go with that, in terms of embroidery as well. They talk about people making garments for other people, which tend to be high status people. But you could see that that would kind of sink right through the whole strata, really. So, I think the pool of women that potentially could have worked on the Bayeux Tapestry could be quite large in some respects. And some people have said, well, you know, how experienced were they and how expert were they? And a few other things that can potentially be gleaned out, looking at the embroidery work itself and the skill needed to do that. Now, if any of us were plucked out of the <laugh> out there and asked to do a bit of embroidery work, and I’ve done some myself, you’re not very good to start with, are you? But I think it is something that a lot of people could potentially be quite good at with some training and some time. And I think a lot of Anglo-Saxon women would’ve had that naturally in the course of their lives.

JA: There have also been thoughts about the age of the embroiderers:

Michael: Other things people talk about, which I think are really quite interesting is in terms of, you know, how good is your eyesight and what impact does that have on, creating sort of textile works. So, i.e. are these mostly likely to be younger women than older women potentially. Also, what sort of time of the day is best for embroidery, for example, in the winter, is it really a good place to be embroidering inside a house when it could have been quite dark and all you’ve got is the fire. Maybe this is a thing that you would do outside when the light is natural. So, I think there’s kind of quite interesting things here in terms of the mechanics as well as the people that may have produced this. So, in short, I see these as probably what we might call secular people predominantly being brought in to work on this project probably through kind of different sort of local connections based on them having a level of expertise saying that when you look at the Bayeux Tapestry, it’s fairly clear that there are some embroiders who are better than others, probably.

JA: We also don’t know how they were recruited or persuaded to carry out this work.

Michael: What basis were they there, had they been sort of picked out and invited to come and produce this lovely tapestry that was going to tell the history of the Norman Conquest and make everybody feel much better about it all afterwards? Or were they sort of, you know, taken by the cuff and neck to say, right, you’re doing this, get on with it. So, I suppose that might make a slight difference in terms of, you know how they engaged with this project. Maybe they were just grateful of course, that they were getting kind of a good income as well in terms of producing this work.

JA: Clare Hunter has worked as a community stitcher. She is also the author of the much-loved book, Threads of Life, in which she writes about the Bayeux Tapestry. She says that for the women stitchers, there would have been an emotional side to the work but also a physical one.

Clare: They would’ve had an overseer overseeing their work. They were working with difficult materials, you know, wool yarn for those that use it, know it’s actually a very difficult yarn to use because it snags when you work with it, it’s, it’s tricky. It breaks in the needle’s eye. And they were only using four colours. So, there was a very limited palette, they might have had other shades attached to those colours, but only four stitches. And trying to express the whole story of what led up to the Battle of Hastings. And then the ghastly aftermath of the defeat in all those, you know, incredible river of narrative that they made in just those four stitches with their four colours. And so, they had to really think very hard about how to capture, you know, the pounding of a horse’s hoofs. So, all those things were technically difficult. And practically, of course, they’d be sitting for hours and hours and hours over long tables the way they sewed. They would have one hand underneath a frame. The other hand on top, repetitive strain injury must have been something that they experienced. So, I think all that would’ve made it arduous. I think it would’ve been a difficult task. And, of course, it would’ve taken years.

JA: On the other hand, they had the solidarity of sitting together:

Clare: And what I think is interesting is in the Bayeux Tapestry, while we’ve got over 200 horses, over 600 men, over 500 other animals, we actually only have six women. And those six women are depicted as being smaller than any of the other figures in the tapestry. So it is thought, and I do believe this, that the women inserted those images covertly and basically put in these tiny, small cameos of what their own experience was. And that’s where we get to the kind of emotional sense of what it was like for those women to sew. Because what they were having to revisit was their own trauma in terms of that battle, in terms of defeat and sewing it down, sewing down their own dead and wounded soldiers, their own men folk and sewing their own places that had been decimated. So emotionally, I think it must have been very heart-breaking at times for them to depict what was there. But then as I say, they put in these tiny images, a woman holding the, the hand of her son fleeing from a burning house, another woman being advanced upon by a man with, an erect penis which suggests rape. Different kinds of images that would’ve been dangerous, but which they were determined to put in some evidence of their own personal testimony of what their experience was like. So in that sense, you’ve got this sense of a different kind of camaraderie between the women themselves saying, yes, let’s do that. Let’s put in that image. He won’t see it. The overseer won’t notice it, but at least our story will live on. So you’ve got the emotional heartbreak of what they were pursuing and the emotional defiance of what they were then inserting themselves.

JA: Michael and others believe the Tapestry was started around 1070 and it was commissioned by Bishop Odo at a time when the Normans still believed that the English would welcome them.

Michael: When William Duke Normandy came over and became King, he believed himself that the English would embrace him. He felt that that was the natural thing that was, was going to happen because he’d been promised in his view the Kingdom of England. And when that didn’t quite happen he uses, these various tactics really to try and bring the Anglo-Saxons inside. Sometimes he befriends them, sometimes he punishes them. And you can see these different activities at play, which obviously happens nowadays in a modern political environment as well.

JA: And Odo’s Tapestry is part of that play – it’s an attempt to tell the story of the Conquest in a balanced way that tries to do justice to both sides, it’s a piece of political story telling, trying to get the conquered to accept their fate.

Michael: I think what’s interesting about the Bayeux Tapestry is the story is not one of Triumphalism really, in a way. It’s clear obviously what happens in the Bayeux Tapestry. It’s not kind of mixing its words, you know, it kind of shows the Normans beating Harold at the Battle of Hastings and the events leading up to that sort of result happening, if you like. But there are things in the tapestry which are much more balanced, I think, when you look at some of the other sources. So, if you read, the typical Norman sources, they’re really, really championing William in particular and the Normans in general at the expense of the Anglo-Saxons. And you don’t really get that in the Bayeux Tapestry in quite the same sort of way. It’s a bit more of a balanced account, I think of those, those years.

JA: But the problem for Bishop Odo was that about the time he commissioned his tapestry William realised that his softly, softly approach doesn’t work and to survive he has to be much tougher.

Michael: But then he sort of snaps and he is had enough of these Anglo-Saxons, and from about the late 1060s, early 1070s, His regime is, is more of one of oppression rather than trying to, to work with the, the Anglo-Saxons. I suppose what’s really important about this period is, is there’s an assumption that William came over you know, beat Harold at the Battle of Hastings became crowned King at Christmas Day, 1066, and everybody just said, okay, thanks very much. We’ve got a new king. Let’s just kind of relax now. But that’s exactly not what happened. There was kind of rebellions, you know, all through pretty much William’s reign, some of them very destabilizing. And now of course we know that, you know, that William was able to, to keep the crown on, it was passed onto his sons and, and, and, and, and onwards. But that wasn’t, I don’t think, any means certain in 1066 or 1070s when the Bayeux Tapestry potentially could have been made.

JA: And that left Bishop Odo with a problem – one that is ultimately vital to the survival of the Tapestry:

Michael: It’s kind of interesting that you’ve got the Bayeux Tapestry being, being produced with a more nuanced and balanced version of history in a period where that sort of goes out the window. And, you know, Odo is basically told, well, this doesn’t really work with the new political reality. So, you can’t really use it in the way you thought. So perhaps it could have been, you know, while Odo was establishing himself in Kent and the Normans were establishing themselves throughout the country that this object would’ve been taught to, to various places, and somebody would’ve presented in front of it and said, well, this is what happened. And Harold wasn’t that bad, but, you know, you’ve got William now. And that all just didn’t really work later in as we went into the 10 seventies. So Odo is sort of left with this thing to think, well, what do I do with it? And that’s probably why it gets presented to Bayeux Cathedral. Then it may be changed from something that had a purpose to something that is more like a gift, I guess that kind of recounts, if you like his life in, in terms of the Norman Conquest. That’s my kind of working theory at the moment in terms of the, the purpose of the Bayeux Tapestry.

JA: And down the ages the Tapestry – as a slightly puzzling gift – stayed more or less safely in Bayeux, brought out only on special occasions, allowing it to survive nearly a thousand years. Clare Hunter believes its continuing emotional power lies in the fact that it is a tactile narrative:

Clare: It was really interesting when and I think the 19th century, they sent over an artist to draw the Bayeux Tapestry in its entirety for the London Society of Antiquaries. When they actually got the drawings back brilliant, though they were, they didn’t capture the essence of the tapestry. And so basically, they made a mould of it. Now, the only reason they could have done that was in order to capture its textual presence, it’s three dimensionality in the stitching afforded it. Because it’s in that, that lies its emotional potency.

JA: Clare understands the power of stitching very well. She is one of over a thousand stitchers who helped to create a modern tapestry that has just the same kind of charismatic impact as the Bayeux Tapestry. Its scope is much bigger than the tale of a battle – instead it reframes the story of an entire nation, 10,000 years of history in more than 160 beautifully worked linen panels. The Great Tapestry of Scotland is the biggest community arts project ever undertaken in Scotland.

Alistair: I often talk about the music of this thing. You can walk around this tapestry, and if you listen really close, you can hear its music. And that music is played by women, completely played by women. And that makes it a unique cultural artifact, in my view. And something that Scotland badly needed. And now it’s got it.

JA: That’s the historian and author Alistair Moffat who was one among many who played a major role in bringing the Great Tapestry of Scotland into being. One of the wonderful things about this modern tapestry – which exercises just the same kind of hold on those who see it as the Bayeux Tapestry – is that we have a wealth of information about how it was created and who made it. Alistair got involved when he was rung up by bestselling Scottish author, Alexander McCall Smith, who asked him to go and have a look at a tapestry on show in Edinburgh, which was about the Battle of Prestonpans.

Alistair: I thought, tapestry, how old fashioned, how strange? And yet, as somebody who’s been in, I suppose, the entertainment business all my life, I, I looked at the faces of the people looking at it, and they were enraptured. And so, I rang Sandy back on my mobile and I said, this is brilliant. He said, yes, why don’t we do a tapestry of the history of Scotland? And why don’t you do the narrative? And I said, okay, two conditions. One, we call it the Great Tapestry of Scotland. And two, nobody interferes with me. Nobody tells me what to do. It’s my narrative or nothing. And he said, fine, fine deal. Done.

JA: Alistair worked with the designer Andrew Crummy to draw up cartoons of different scenes from Scottish History that Alistair thought should be included:

Alistair: First of all, it’s gotta be people’s tapestry. We can’t have the tired old procession of kings and queens staggering across the landscape, you know, boring everybody to death, battles and all the rest of it. Or Columba, you know, hectoring the sinful in the Highlands. What we need is something that is about Scotland’s people. That’s the first thing. Second thing is, it’s gotta be all over Scotland. It can’t just be Edinburgh, Glasgow, and, you know, Bannockburn and the good bits, it’s got to be all over Scotland.

JA: And one of the wonderful things about this tapestry is that it includes the fabric of ordinary people’s lives: this isn’t just the story of elites.

Alistair: And I came up with the idea of doing generic panels. So, we would do weavers, fisher lasses, we would do people who made linen. We would do people who, who worked on the land, ploughmen and so on. We’d do the harvest, because these are eternal things, and ordinary people did that. And so that worked. And the other thing I was very keen to do is to have a laugh. You know, we couldn’t be too po faced about it, because that’s just boring. And so in the tapestry, The Great Tapestry, there are lots of good jokes.

JA: The critical figure in creating any tapestry, particularly one as ambitious as this, is the Head Stitcher. Andrew Crummy – the designer – and Alistair had someone in mind:

Dori: <Laugh>? I thought they were mad <laugh>. I, I think I was a bit living in denial slightly because I was thinking about the practicalities of it all. And as more and more panels that Andrew had drawn came into my studio, which was then called the Hub we were in separate places, they just kept coming and they just kept coming.

JA: Dori Wilkie had been the head stitcher on the Prestonpans Tapestry – but this was a much bigger job. She and her volunteers had to select the colours and the variety of stitches for the panels, order the linen and the wool and cut it all up into different kits and send it out to the stitching groups the length and breadth of the country:

Dori: I made up three pages of suggestions of what stitches could be used what they could do. They could you know, just enjoy it, use your imaginations. Most of the volunteers were in groups and so it was keeping contact with them. Gillian helped me allocate the panels and we allocated them according to geography and where the volunteers were living as much as possible and subject. And so, hobbies were listed on this form that was sent out to anybody who applied to do it. And I was very keen, it wasn’t just Embroiders Guild ladies and rural ladies, I wanted hobbyists, people who couldn’t sew and there were a load who couldn’t sew. And they got themselves involved in this, this project, a meter square of embroidery. But they soon learned, because there’s a lot online <laugh>.

JA: Some people were overwhelmed by what they had taken on, others simply put theirs away and didn’t take it out for months, and others got started straight away. Dori had ten volunteers working with her in the hub, tackling inquiries and questions from the 60 stitching groups.

Dori: There was a lot of angst at the beginning and worry that they would get it wrong and they had to be reassured nothing was wrong. They thought that perhaps they had to do all traditional stitching and it would be judged. But as we had halfway through making the tapestry, we had a meeting and it was called the blather. And all the groups came along that could with their, their panels at whatever stage, and they could see each other’s panels and get excited about how, oh, they’ve stitched that, like that we weren’t sure what to do, that’s what we’ll do. Or see how loosely they could stick by loosely I mean avoiding necessarily tradition, you know, building up textures and things like that. And then it turned into research and how, how do you stitch molten steel? Well, how do you stitch <laugh> molten steel? But you should look at the panel, it’s beautiful. So, they got ideas from each other, loosened up, began to get excited about the end. There were many reports of stitching till three and four in the morning exhaustion, exhilaration when it was done. And they just felt as if they’d been bereaved once the panel went away because they’d spent so much time working on them.

JA: There are tremendous stories that come from this time. One panel was allocated by post code to the Outer Hebrides, unfortunately the two stitchers lived on different islands, with an hours ferry crossing between them. Between January and April each would stand in howling wind and heavy downpours on jetty slipways to hand over their precious cargo to the obliging ferry men for onward transmission to the other stitcher.

Dori: It’s storytelling and stitching and working with thread is therapeutic. And very often we had people saying, oh, I’ll just sit down for five minutes and stitch and then four hours later they’re still working on it. A lot of problems were solved, sitting, stitching, and a lot of friendships were formed. So, it, I can only think of beneficial once you get over the initial shock of stitching on such a large scale. I can only think of therapeutic moments, stitching and problem solving and bonding, a lot of women bonding and men, there were the occasional men who stitched and did a wee bit. But the other thing was it brought in all the network of all these stitchers who had expertise on geography of the age area, the history, the whatever. So, there was an inclusiveness with it as well.

JA: And in time the stitchers asked for more of their own stories to be included and to me these are some of the most beguiling panels.

Dori: A lot of women were saying, why is there not more about the women’s history? And so about 40 half panels, as we called them because they were a meter by half a meter, were added depicting jobs that women stereotypically did. So, in the washer woman one, for example one of the stitchers’ grandmothers had to do work because her grandfather fell and couldn’t earn money for the family, so she took in washing. So, she remembered her grandmother, for example, used to roll down her stockings down to her ankle and had these pinnies that tied at the back and the other grandmother used to sew teddy bears for charity. So that’s depicted in the panel as well.

JA: Clare Hunter believes that the Great Tapestry of Scotland is a powerful record partly because it is the work of so many hands:

Clare: Because it has been stitched by a thousand women and a few men throughout Scotland, then it’s an authentic testimony. It’s not the narrative of one person. It’s actually the kind of evocation if you like, by a thousand different people of their country. And a lot of those people are sewing, it’s bit of a history which belongs to them part of their place, part of their community, part of their legacy. And so the kind of authentic testimony of it, I think gives it another kind of power. And it’s both a celebration and it is a commemoration. So, imbued within it are the thoughts and the knowledge and the, and the emotions and say of the people who sewed it. And I sewed a footballer <laugh> in mine. We, we group of us from ow got together and and then we, we, we basically posted it to each other and we got the football panel, which we were a bit disappointed about at the time because we’d wanted to have something much more kind of well, not the football isn’t interesting, but you know, something, a river in sea and landscape, or a battle or something might have been more riveting But, as my great-great-great grandfather, been one of the founding member members of Celtic Football Club, then although this doesn’t address any particular club, then I felt that I was actually sewing part of my own legacy when I did my footballer. You know, I have to say it was very frustrating to sew because of that wool yarn, but I was very glad to put my little bit into the tapestry.

JA: The Great Tapestry of Scotland draws some of its inspiration directly from the Bayeux Tapestry, the centre was designed by Andrew Crummy, but the borders going around each panel – subdivided into squares – was left up to each stitching group to fill as they wished. Dori says the stitchers of a thousand years ago were present with them.

Dori: My feeling about the embroiders of the Bayeux Tapestry is that this was perhaps their work depending who did it. And these were people who more commonly did this type of embroidery, but also it made us think about working together as people. I think it’s this feeling of kinship doing something and just referring back to them and thinking about the days when women were really tied to the house and had to do housework and chores constantly, but had sewing bees and how they left to do that, whereas people sewing the Bayeux Tapestry probably this is what they did routinely. And then we saw the value of women getting together and talking through problems and encouraging each other with life. So, yes, we thought about them a lot, but we also thought about them more as an influence on what we were actually doing and carrying forward.

JA: Eventually the day came when all the panels were finished. No one had given a great deal of thought about what happened next. Here’s Alistair Moffat:

Alistair: Anyway, so it came to the point where we had to decide how we would show it for the first time. Now, I knew the guy who, who ran the Scottish Parliament, and a lovely man, Paul. And I said, we’ve got this tapestry, Paul: We’ll show it, he said, we’ll show it at the Scottish Parliament, it’s the only place to do it. I said, but you haven’t seen it. He said, I don’t care. It’ll be good. I’m sure it’ll be good. I’m sure it’ll be good. And so we agreed that we would show it in the foyer of the Scottish Parliament, <laugh>. And I remember parking my car in the Queens Park in Edinburgh, and walking across for the sort of evening preview, you know, the, the evening launch thinking, oh geez, there’ll be three men and a dog there. It’ll be awful. And I got in I’ll never forget this, and I could see away in the corner of Sandy McCall Smith and Andrew Crummy, and Jan Rutherford and various others. And I thought, I have never seen this tapestry hung together. I’ve seen of individual panels, but I’ve never seen it go from one to a hundred and sixty-five. And so, I started to walk around, and after about five minutes, the tears were running down my cheeks. I couldn’t believe how powerful it was. It was amazing. What these women had created was staggering, staggering. The thing just sang in a way that I’d never, ever possibly been aware that it could.

JA: He returned the next day:

Alistair: I went back, because it was the first day open to the public thinking, yeah, okay, well, maybe I liked it, but you know, who else is gonna give a tinkers toss? And there was a queue round the block, there was a queue round the block to see it. They couldn’t cope in the Scottish Parliament. All the officials were really worrying about the capacity of the foyer and the adjacent rooms to cope with the number of people. Alex Salmon was First Minister at the time, and he made a joke in the chamber saying he thought it was people waiting for First Minister’s questions, <laugh>, but essentially it was rammed. People were desperate to see it.

JA: The same thing happened wherever they took the tapestry across Scotland. Thousands of people came to see it. And when the tour came to an end Alistair Morton was determined the Tapestry would have its own bespoke building in the old Borders textile town of Galashiels:

Alistair: It was a fight to get the money. And, you know, I’ve done an enormous number of Burns suppers. I can tell you as political favours, <laugh>, this is so hard. But basically it was, the whole thing was a labour of love. It really was. You know, I I, I’ve, I’ve been doing this since 2010, God you know, involved in it in some way or other. And here I’m still <laugh> involved in it.

JA: Last Year King Charles and Queen Camilla came to visit and Alistair showed the Queen around.

Alistair: The women who made this made something completely unique. It’s the only huge, all-encompassing history of Scotland written by women, made by women, not by men, but by women. I mean, there were five or six guys and about a thousand women who made this. And the Queen said to me, and what did the men do? I said they made the tea.

JA: And I doubt they did that for the women of the Bayeux Tapestry. Trip Advisor now rates The Great Tapestry of Scotland among the top 10% of the world’s attractions, many people come back and back:

Alistair: Even though I know everything that’s in every panel, I still get surprised by it. I mean, you forget stuff, of course, but I still get surprised by it and taken aback by it. And I love that. I mean, how many things in your life do that to you? Very, very few. And it’s also about it’s about a place we love. I remember Joanna Lumley saying to me, this is a love story. This is a love story. This is what it is, darling. It’s a love story. And she’s right. That’s what it is.

JA: There is something about these embroideries that connects us at a heart level to these stories, perhaps it’s the quality of thought or time that has gone into them, or maybe it’s just a rest from written words that makes them so much more accessible and allows us to read our own meanings into them, but never under-estimate the power of stitch to re-define who we are and how we see ourselves.

Thank you to everyone who took part in this podcast and especially all the stitchers, living and now dead, who contributed to both The Great Tapestry of Scotland and The Bayeux Tapestry, you have all done something truly incredible. If you find yourself are anywhere near Galashiels or Bayeux do go and visit.

You can find out more about this episode, and see a full script and pictures at www.hapticandhue.com/listen-series-7 Haptic & Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and edited and produced by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production generously supported by our listeners, who fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue.

At the end of last year, 2024, Friends of Haptic and Hue adopted two stitches from the Royal School of Needlework’s Stitchwall, which is an effort to preserve the human heritage of every stitch in the world: and yes one of the stitches we have supported is Bayeux Stitch – one of the principal stitches used in the Tapestry – if you would like to find out more have a look at the web-page for this episode.

And If you become a Friend there’s an extra podcast every month – called Travels with Textiles hosted by Bill Taylor and me, where we cover a whole range of different textile stories and news. This month we will be looking at another very special tapestry that tells the story of oil, coal and climate change. But until then – its goodbye from me and enjoy whatever you are making.