Episode #54

Jo Andrews

Sailcloth has been vital to humanity down the centuries: without it the Greeks could not have fought the Trojans, there would have been no Viking empire, William the Conqueror would not have invaded England, the Polynesians could not have settled the Pacific, Columbus certainly would not have sailed the ocean blue, Magellan would not have circumnavigated the world and there would have been no transatlantic slave trade.

Sails made so much possible. But even though these events form the structure of our history and cultural heritage, there has been very little focus on the sails that made them possible, and almost none on the communities that made the sails. This episode of Haptic & Hue looks at the most ancient sails we know about and takes us right up to the sails used for modern yachts. We talk to a craft sailmaker and hear how a small village in Somerset was once at the heart of the global industry of sail-making. We also hear from a Danish textile archaeologist about why Viking sails were unique.

Notes:

Lise Bender Jørgesen is an Emeritus Professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in the Department of Historical Studies. Her books include Creativity in the Bronze Age – which you can find in the Haptic & Hue US Bookshop and the Haptic & Hue UK Bookshop and The Roman Textile Industry and its Influence – also in the UK Bookshop

Ross Aitken can be found at Dawe’s Twine Works in West Coker. They welcome visitors on the last Saturday of every month. They serve excellent coffee and cake and they will give you a wonderful tour of the twine works. The new book just out about Coker Canvas, called Bucked in The Yarn by Terry Stevens, can be bought there, from Haptic and Hue’s UK bookshop or from online booksellers. Dawe’s Twine Works is also on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/dawes_twineworks/

Mark Matthews – heritage sailmaker is on Instagram as: https://www.instagram.com/mmsailsolutions/ He also works at the Boat Building Academy in Lyme Regis in Dorset https://boatbuildingacademy.com/ You can find out more about the UK’s Heritage Crafts Endangered List here

Professor Lise Bender Jørgensen

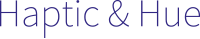

The Naqada II Jar, image copyright British Museum

The Twine Walk, Dawe’s Twine Works, West Coker

Ross Aitken at Dawe’s Twine Works, West Coker

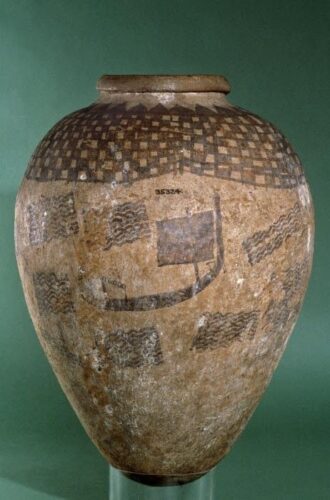

Relief of a Roman Sailing ship from Ostia in Italy

Replica Viking Longships – Wikimedia Creative Commons Licence

Inside the Twine Walk, Dawe’s Twine Works, West Coker

The Old Office Dawe’s Twine Works

More String Dawe’s Twine Works

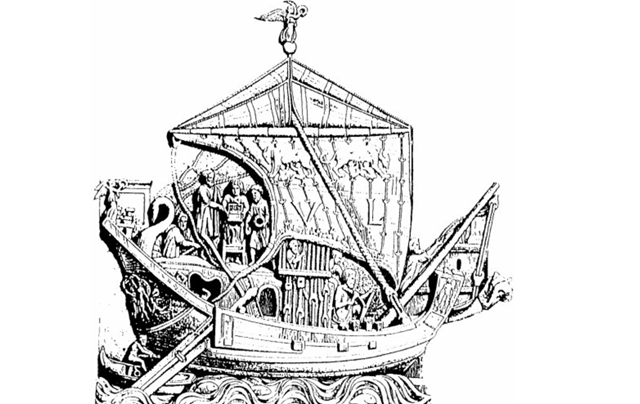

The Mayflower in Plymouth Harbour, by William Halsall. Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Buttersworth HMS Victory in full sail Wikimedia Commons

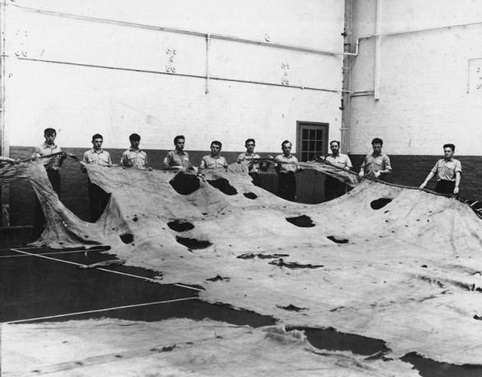

HMS Victory’s fore topsail displayed in the 1960s After Being Rediscovered

Mark Matthews – Sailmaker

Script

Plain Sailing: The Cloth That turned The Tide of History

JA: Sometimes when I say Haptic & Hue is about textiles people say: “oh that’s niche”. I don’t think textiles are niche, I think they are central to our history and culture in ways which are often not well explained and which haven’t reached the standard text books. Are sails niche? This is a simple coarse fabric that for millennia enabled us to move about this planet. Sails were the very stuff of travel, trade, exploration, war and empire. Without sails there would have been no Greek and Trojan Wars, no Viking empire, no Columbus or Magellan, the incredible Polynesian navigators would not have made it across the Pacific, James Cook could not have arrived in Australia, there would have been no Mayflower carrying pilgrims to America, or transports taking convicts to Australia and there would have been no Trans-Atlantic slave trade. But no-one has paid much attention to the sails themselves, who made these incredible pieces of technology and the impact they had on their communities.

Professor Lise Bender Jorgensen: I think there are a couple of reasons. one of them is that there’s hardly any preserved evidence of prehistoric sails from antiquity. They are organic materials, and they quickly disappear. And also, what we find is often fragmented and how to recognize a piece of a sailcloth in a fragment. Another reason is that textiles are studied by women (laughs), again, this is not quite taken seriously. It’s also because the industrial revolution has meant that textiles are now produced in huge numbers. we have forgotten the relationship between labour and raw materials because we can go to the shop and buy a nice dress or whatever for hardly any money made in Bangladesh or whatever. It’s made by badly paid people in the other parts of the world. And the raw materials are rarely the traditional ones, like flax or wool. It’s polyester.

JA: Professor Lise Bender Jørgensen – is an internationally regarded expert in prehistoric textiles, and I’m Jo Andrews, the host of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles and a handweaver interested in the stories fabrics tell us. Often the hidden hands that fashion fibre and cloth into something useful and beautiful have something new to tell us about ourselves and our communities. Sails are the very stuff of history and yet we don’t know when they were first used. The earliest depiction of a sail we have is on a vase in the British Museum and it shows a small river boat from the Nile:

Lise BJ: That’s from Egypt, from pre-dynastic times, about three and a half thousand years ago. One of those reed river boats with a mast and a square sail at one end. The Egyptians had sails, and, they also like to make models of all kinds of things, including ships. So, there are little ship models with small sails. So, I would say that’s, as far as I know, those are the earliest.

JA: But Professor Bender Jørgensen says we mustn’t assume the Eqyptians invented sails.

Lise BJ: it’s always very difficult for to argue from lack of evidence. I would say we have evidence from Egypt. We haven’t from as far as I know from anywhere else. But, inventions, rarely only appear once. We’ve seen that with a lot of archaeological things like agriculture, that for long it was thought it all started in the near East. But then when, American archaeologists started looking in their region, that was also their invention of agriculture. And of, of course agriculture has been invented many places, <laugh>, so, you should never say never. And, they could easily have invented sails other places like Mesopotamia, or China is often very early with a lot of things. but if we haven’t got any evidence, we can’t say so. <laugh>.

JA: But the oldest pieces of actual sailcloth we have come from around two thousand years ago. Fragments of a sail survive because it was torn up and used as packing for a mummy– a lovely piece of repurposing. Others come from the Red Sea and also date from Roman times. Several pieces were discovered in a port called Berenike near the border with Sudan. The textile specialists archaeologists working on textile remains from an ancient rubbish heap, Felicity and John Peter Wild, recognised that what they were looking at was a sail.

Lise BJ: It was fragmented, but, it was a piece of fabric with some strengthening, some bands, ribbons, and I think she knew about the sail from a mummy wrapping. She could also recognize that this was the way sails in Roman ships were constructed. You can see it in various images and they also found what’s called brailing rings that were used to attach the sail to the beam. Then, at more or less the same time, another team were excavating at Myos Hormos, the other Roman Port on the Red Sea. And of course, they found similar once they were recognized, you can find more.

JA: The port of Berenike was founded the Pharaoh, Ptolemy II to import war elephants to Egypt, which must have been an incredible sight. Later when the Romans conquered Egypt, they used the harbour to import all kinds of things from India, Arabia and East Africa. What the Wilds found was that they could tell the difference between sail fragments that were made in Egypt and those that had been made in India or Sri Lanka because the yarn was spun in the opposite directions.

Lise BJ: Of course, the trade came in from India, and the ships were Roman. But of course, when they went to Sri Lanka or to India, they would’ve needed repairs. And so, when they came back some of the, the sails were made of Indian cotton. Well, it would be necessary. Tell any sailor, <laugh>, even modern sailors, that, if you’re going on a long distance trip, you need to be able to have repairs made.

“And flashing eyed Athena sent them a favourable wind, a strong-blowing West wind that sang over the wine-dark sea. And Telemachus called to his men and told them to catch hold of the ropes and hoist sail, and they did as he told them. They set the mast in its socket in the cross plank, raised it, and made it fast with the forestays; then they hoisted the white sails aloft with ropes of twisted ox hide. As the sail bellied out with the wind, the ship flew through the deep blue water, and the foam hissed against her bows as she sped onwards. Then they made all fast throughout the ship, filled the mixing bowls to the brim, and made drink offerings to the immortal gods, but more particularly to the grey-eyed daughter of Zeus. Thus, the ship sped on her way through the watches of the night from dark till dawn.”

JA: Homer recording Telemachus setting off in search of his father – Odysseus – who had been missing for years. It’s a beautiful depiction of a culture that understood the power of sails and built a successful empire on the back of them, even though nowhere does Homer recognise the labour of creating sails. But it’s a description that would fit many times and many cultures: around a thousand years later much further north, the Vikings could be found doing almost exactly the same thing, except that, extraordinarily, some of their sails were made not from linen, hemp or cotton but from wool. Here’s Lise Bender Jørgensen:

Lise BJ: People everywhere made sailcloth out of the fibres that were available to them, and that’s probably why wool sails were made in Norway, because, sailcloth, tended to be made either of flax or of hemp. Those are the two main, materials or cottons as, as we’ve seen in, in <laugh> in the Red Sea harbours, that is plant fibres, but, along the Norwegian coast, you don’t have very much arable land.

JA: So the Norwegians didn’t have the flat land to grow hemp or linen, although Professor Bender Jørgensen thinks they tried.

Lise BJ: I looked at pollen diagrams for the Norwegian coast, especially in northern Norway. And I could see that, around 750, there was sort of a flurry of hemp and flax, but it disappeared. And, I imagine that’s my theory, that, when they wanted sailcloth, they first tried to do like further south, grow flax and hemp, and then found out it was a question of priorities, fibre, or food. What should you grow? Should you grow food? Or should you grow fibre? And in my opinion, they opted for food. At the same time, you could see that, there’s a special kind of landscape along the Norwegian coast, called coastal heathland, there are plenty of little islands, lots of them are not inhabited by humans, but they’re excellent for sheep who can in fact live there all year round. They eat seaweeds, and are quite happy. At that point, around 750, you can see that the coastal heathland, it grew. So that’s why I think in Norway, they probably did a lot of wool sails, because that was the fibre they could make without much problem.

JA: Around 25 years ago a number of museums and universities across Scandinavia and in the UK got together to answer a number of questions about the Vikings including reconstructing a woollen Viking sail, to find out EXACTLY how it was made and why it worked.

Lise BJ: What is it that makes a web suitable for sailcloth? Is it the weaving, the binding? Is it the fulling, or is it the dressing of it? The University of Manchester, they at that point had a Department of Textiles and one of their professors, Bill Cook, he took charge of a lot of investigation, including, the question of air-permeability. And, his results were quite clear. It’s not the weaving, it’s not the fulling that hardly made anything. It was definitely the dressing, or as he called it, the smørring <laugh> <laugh>. He had adopted a Norwegian word, <laugh>, for what was a combination of, tallow and fish oil, and ochre.

JA: It’s amazing how far good wool, tallow, fish oil and ochre can take you, but what is also is interesting is that this project enabled Professor Bender Jørgensen to understand some of the incredible labour that went into equipping a Viking warship. Her estimates show that for just one ship it would have taken 50-60 years of labour, and that at its height the Viking Fleet would have need a million square metres of sailcloth. Sails were a great success but the work of producing them meant more sheep and a reorganisation of society. No-one is sure how this was achieved: were there slaves to do the work? Was there a kind of putting out system with weaving workshops organised by the nobility? Lise Bender Jorgensen has a different theory.

Lise BJ: Those who went to Britain, et cetera, they usually were sort of what we would call noblemen and they had their followers, and if that was a local nobleman, he would be head of a, a number of farms and a number of cottages, and then it could be that a cottage should supply so and so much warp yarn a year, another cottage, similar amount of weft yarn, maybe one of the smaller farms should weave a length of cloth, et cetera., In that way it is not industrial, it’s a simpler system, and something that’s feasible within the household economy, in a rural setting. Of course, it would have meant a lot of extra work. So, I think it’s important not, to imagine that you had to make 1 million square metres of a cloth tomorrow. <laugh>,

JA: But the point here is that it took a community to turn out a good sail and certainly to equip a fleet. To me these really are the hidden hands of history. The creation of sails has changed the tide of human events over and over again, but the Viking, Egyptian or Greek spinners and weavers, many of whom would have been women, are forgotten, erased from the record, whereas the explorers and sailors who launched their expeditions on the back of those sails are honoured down the centuries. Sails were important technology and those who had the best, had a chance of commanding the sea. By the 17th century, as we truly enter the age of sail, some of the finest sails in the western world were to be found in a set of small inland villages in Somerset, that come straight out the English Tourist Board’s lookbook. East, West and North Coker are built of Ham Stone, once described as “the colour of biscuit, sprinkled with gold”: Here’s Ross Aitken, who was born in the Cokers and is the founder of the Coker Rope and Sail Charities.

Ross: Three little villages, you’re 20 miles inland, you know, why the dickens does a sailcloth of such importance grow up there?

JA: And no-one should doubt the importance of Coker Canvas – it became a world beating standard – a global brand that was adopted by pirates and navies alike, this is the sail-cloth they all wanted. So, what’s the magic of the Cokers?

Ross: But the reason is that the soils here, they grow hemp and flax, which is the basic materials for making cloth and twine and rope, grows better in this area than anywhere else in Great Britain. And it’s a band of middle Jurassic corn brash. And the soils on that grow hemp and flax better than anywhere else. The reason is that there are layers of what are called doggers in this geological formation, which means, and they’re impervious, which means there are springs everywhere here. And what hemp and flax likes is a damp soil. And so that’s why these soils are so good for it. And that’s why the industry built up here.

JA: Ross who is a former geologist and one of those wonderful people who has dedicated a big chunk of his life to unearthing and conserving the Cokers’ place in history, says archaeological digs show that sail production goes back to the 1300s, but what really put Coker Canvas on the map was the inventiveness of local people:

Ross: The entrepreneurs were very good. They realized the potential of it and put money in to develop it. The Industrial Revolution came a bit late to Somerset, I’m afraid. So, we are talking about the 1870s before there was any real machinery here at all. And so, all the weaving of sailcloth was done in cottages and in all the villages around here that’s what your wife and daughter did. They turned yarn into Sailcloth, oblongs of Sailcloth on the loom, and the looms were fixtures, so when the cottage was sold, that loom stayed, because that’s what your wife and daughter would be doing. And so, the whole of this area of southern Somerset and north Dorset was all tied up with either growing hemp and flax or turning it in to yarn or turning that yarn then into Sailcloth and rope.

JA: And the Cokers came up with a way of making sailcloth that made it stronger and longer lasting than anyone else’s:

Ross: The unique thing about Coker Canvas was that it was bucked in the yarn and not in the piece, that unintelligible phrase is, bucked is bleached, and the piece is the sail. So, what was different with Coker Canvas was they bleached the yarn before they made sails out of it. Everybody else bleached their sails, which meant, of course, that you weakened the sails in some places where the yarn wasn’t up to standard and you couldn’t do anything about it. Whereas if you bleach the yarn first, you throw away the yarn you’ve damaged. And so, Coker Canvas would last usually about twice as long as anybody else, and that’s why it became so important.

JA: We heard from Lise Bender Jørgensen that the Romans had to have their sails mended in India and Sri Lanka, and here is the same problem over again years later.

Ross: Do remember that the average sail only lasted eight months before it was rotten. So, if you began to think about the Navy, the Merchant Navy, pirates, everybody, just begin to realize that the requirement for Sailcloth was enormous. And so having a sailcloth that lasted longer was really, really important.

JA: Admiral Nelson’s Flagship, The Victory, carried Coker Canvas at the Battle of Trafalgar. By this stage sailing ships were enormously complex and the sails that powered them had multiplied.

Ross: A ship like Nelson’s Victory at Trafalgar had a full complement of about 60 sails, of which it set 32. And you would have two or three sail makers on board because for when they split and everything. So, they would keep them going. These ships were just awful. I mean that, first of all, they were at the beginning of the voyage, they were terribly crowded because they expected at least half the people to die during the voyage with scurvy and various other things.

JA: Each sail was made of strips of canvas sewn together by hand.

Ross: So, the smallest sail on the Victory was its top sail, and that had one and a quarter miles of twine in it to sew the oblongs of sailcloth together.

Jo: And the largest sail?

Ross: Yeah. Don’t think about it <laugh>. the reason for it is because it was so much bigger, and of course there were different weights of canvas. So, you would have heavier weights of canvas on the sail, the main sail, because they, were really propulsion, whereas some of the other sails were more for direction than propulsion. And so those sails weigh several tons, and that’s dry. Think about it when it’s wet, and then think about putting those sails up in a storm or taking them down, more likely, it must have been horrific.

JA: Nelson’s topsail from the Victory still exists, it’s at the Royal Navy’s National Museum in Portsmouth pierced more than 90 times by enemy shot. Nelson was a fan of Coker Canvas – but it cost more than other sailcloth – and the Royal Navy, which had a lot of ships to outfit, preferred to save money and buy cheaper canvas, but some US Navy ships were fitted with Coker Canvas:

Ross: Yes, it was very interesting actually, because they learnt quite quickly it was very useful, in fact, quicker than we did. And in the 1830s, there was a battle between the USS Constitution and a couple of English ships. And the USS Constitution out sailed the English ships. It was sailing with Coker Canvas and the English ships were sailing with Dutch canvas.

JA: But eventually even the British Navy gave in, and Coker Canvas became the pattern standard for all its ships. The Cokers thrived as a centre for sail-cloth and their method of bleaching the yarn first and then weaving the cloth became adopted world-wide, and as long as there were sails there was Coker Canvas. But all good things come to an end. And as the age of steam replaced the age of sail, the Cokers had mouths to feed and hands to busy. These small villages did not fail: instead of making sailcloth they turned to making twine, string, and rope:

Ross: And first of all, you turn it into the yarn and then twine, and the twine then is turned in, turned into rope. So, in this village alone, there were six twine works. And so, it gives you an idea of the amount of employment that was going into it. So, all that employment that had been for sail cloth was now to make twine that was turned into rope, mainly in Bridport. And Bridport still is at the top of the rope making worldwide. So, the arrestor cords for the space shuttle are made in Bridport. If you’re keen on tennis, Wimbledon, all the nets are made in Bridport. So, the big industry in rope and twine is still there.

Ross and I talked at the old Dawes Twine Works in West Coker. Ross and a dedicated community of volunteers have spent many years restoring it to its former glory, including one of the only twine walks left in Britain – a long covered space where you could wind twine into long lengths. The Dawes office is also a delight, full of string for every kind of packaging and wrapping – some of it deeply mysterious.

Ross: That in a way has been such a fascinating part of putting this twine works back together, is learning the history of twine and sailcloth, and suddenly learning how important these three villages were worldwide. I mean, this is not a small trade you can imagine. You know, that’s how we moved around on the sea, and for centuries were sailcloth and these villages were at the heart of that trade. So, they were incredibly important. And, you know, heart three very nice rather sleepy villages now, but they were the heart of international trade for 300 years.

JA: Today sail making is an endangered heritage craft and there is a risk that these traditional skills could be lost. Mark Matthews is one of the few traditional sailmakers left in Britain –he has his own workshop and the use of a sail loft in Portland – not that far from the Cokers – on the Dorset coast. The materials he is working with are completely different.

Mark Matthews: Okay, so there’s a huge range of different styles of fabric. S,o most cruising yachts will have a material which is polyester based, that’s actually got a trade name of Dacron. Then after that, we look into sort of laminates which are basically layers of material sandwiched together. And the fibres that are laid into those laminates are anything from, carbon to Kevlar, sort of aramid fibre. So, anything like Dynima, Spectra, quite modern style fibres used. So, all those are sort of layered together. And then the other material that’s used is a nylon, which is used for downwind sails. So, when you’re sort of going in front of the wind and going off downwind and you, you quite often see these sails, they’re quite brightly coloured sails on the yachts. So yes, that’s the other, the material that that’s used.

JA: One of the advantages is that the man-made fibres do last much, much longer.

Mark: If the sails are well looked after, then the Dacron can last up to 10 plus years. And because the, the, the polyester fibres in the Dacron they actually have like a resin coating on them and that actually holds the fibres in place. So, what tends to happen is that as the sails get older, this resin, although you don’t see it break down or come off the sail, it actually sort of weakens and goes softer. So, it makes the sail from being quite a firm sort of sale material, it goes quite soft and that’s when the sale starts to lose its shape and the material starts stretching.

JA: But while you can still repair modern sails there’s a problem when the fabric itself degrades often because of exposure to UV light.

Mark: Yeah, I mean, you can still repair the sails. If the material gets to a stage where it’s actually degraded through UV or just general wear and tear, then actually putting a new piece of material to repair that sail, all it’s going to do is actually create like a hinge point, so where the edge of the new material finishes and it then meets the old, that acts like a hinge point,, then the material will just tear along the edge of the repair. So, while sails are in very good condition and the material’s in good state, then yes, absolutely they can be repaired. But once the material gets so damaged to the point where you can actually tear it by hand that’s usually quite a good test in the sail loft is if you can actually physically tear the material, then you know it’s beyond its point of repair.

JA: And yes, when they are finished with generally modern sails get dumped:

Mark: Unfortunately, you know, sails generally have been going into landfill, unfortunately, but there are quite a lot of people now that are actually using the fabric and actually making sort of sail bags out of them. And also, there are a few people that are actually creating artwork from old sails, and then they’re actually sort of painting them or they’re adding, pieces of, of other threads to it. so some of it is being used for that. So, so there are a few ways that it, you know, now it is starting to get sort of recycled and, and reused. Yes.

JA: But the biggest change is that in the past making a sail was the work of many hands, be it a community or a company, think of the hours the Vikings put in for a single warship, or the numbers employed in the Cokers. Today sail-making is a much lonelier task.

Mark: They would’ve had in a sail loft probably up to about 40 people working on, on the sail. And a lot of it would’ve been hand sewing. Obviously the, the fabric itself would’ve been quite heavy, especially, for the, sort of sailing ships at the time. So, you would’ve had many hands working on those sails. So, all the ropes, external rings and, and grommets would’ve all been hand finished, so actually worked by hand to, to finish the sail. So, with now modern sails the materials are actually probably a bit lighter now, and stronger so they don’t stretch as much. And so a lot of the, like the rope work is all internal and inside sleeves and pockets now, and all the rings are hydraulically pressed in. So, the whole process is a lot quicker now. The other thing that, that traditional sails would’ve been is actually laid out on the floor. So when all the panels and all the sections of the sails are put together, they would’ve been laid out on a floor and then joined together. Whereas now in modern sail lofts, all the sails are now designed by computer on a sort of 3D design program. And then there’s actually a cutting table, bit like a CNC cutting table, and you roll the fabric out on this table, and then your designs, basically of the panels, get cut out on the table. So, the whole process now is a lot quicker. So, one person like myself, because I’m self-employed, and, and it’s only me making the sail, I will make a sail from the start all the way through to the finish.

JA: And sails are still sewn together.

Mark: We actually use a really high tack double-sided tape. So, we stick the panels together first, so that holds the material in its shape. And then you have to roll it up, sort of almost rolling up parallel to the, the join lines or the seam lines. And then yes, it’s very much putting it manually, putting it through the machine and sewing the sails up. Yes.

Jo: So, you are a good seamstress

Mark: <Laugh>. Yes, yes, you could say that, I love getting behind a machine and, and sewing with sails, yeah, absolutely love it. <Laugh>

JA: But apart from the sewing, for Mark there is still enormous skill in crafting a good sail.

Mark: Yes, very much so. I think that there’s doing all the finishing, what we call the finishing work, which is all the corner rings and all the edging of the sail and all the sort of hardware and components that go onto the sail. And then also I get the joy of when I’ve, especially if I’ve made a sail for a boat that’s local, I’ll actually go and fit the sail on the person’s boat and if the weather conditions are okay, we’ll like just hoist it up, see it all fits all okay. And check the shape. Looks good, it’s really nice to sort of see the project all the way through from right at the beginning of the design all the way through to actually fitting it on the boat.

JA: Mark also loves getting out on the water and spotting sails – both those that he has made and those made by others. Shortly a sail in original style Coker Canvas may be among them. Ross and his team found, by chance, an old sample of No 1 Coker Canvas in the British Library. He has had it rewoven and Mark is making it into a sail. Mark says that the canvas needs developing into a heavier weight sailcloth – but he’s happy to work with the first bolt of the Coker fabric.

Mark: We’re going to try and get hold of a sailing dinghy which hopefully we can keep at the Twine works, and then I’m going to make a sail for that dinghy. And I’ll make it very much the traditional way and although I’ll still use a sewing machine to actually join the panels together and the sections together, but all the edges will be traditionally finished by hand. So, it’ll have external ropes, external rings and grommets. And then hopefully, you know, once we’ve got that sail, we’ll put it on the boat and see what it looks like. Then hopefully we’ll be able to tow it down either possibly here to, to Portland or Lyme Regis. And yeah, it would be great to have the finished sail on a boat that we can actually then launch and then see the sail in action.

JA: A sail that, like every other, will be the inheritor of a tradition that is thousands of years old. Something that encapsulates the skill and knowledge of countless unknown hands that made this remarkable piece of technology possible. So, the next time you see the wind fill a sail and its seams miraculously hold, remember the work of the nameless people stretching back into the darkness – who made the age of sail, and all that it meant, possible.

Thank you to Ross Aitken and all the volunteers at the Dawes Twine works, if you are anywhere near West Coker on one of their open days, go and visit. It’s a great place for string and textile enthusiasts. And if you are a member of Friends of Haptic & Hue keep an eye out for the next newsletter. Ross gave me a length of Coker Canvas to give away to Friends, but sadly not enough to make your own sail. Thank you too to Mark Matthews and Professor Lise Bender Jørgensen both of whose skill and wisdom adds a great deal to what we know about sails, how they were and are made. You can find out more about this episode, and see a full script and pictures at www.hapticandhue.com/listen-series-6

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and edited and produced by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production entirely supported by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you something extra every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted by Bill Taylor and me, where we cover a whole range of different textile stories and news. This is the last episode in Series 6 of Haptic & Hue we will be back next year with, unbelievably, Series 7. Meanwhile the next episode of Friends of Haptic & Hue is in two weeks’ time. Until then have a lovely time and enjoy whatever you are making.