Episode #50

Jo Andrews

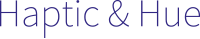

The Rajah Quilt – named after the ship the women were transported on – has nearly 3,000 individual pieces. It is one of the only items made by convicts that survives from this part of Australia’s past, which was buried in shame for so long. The quilt gives us a rare chance to re-assess what it meant to be transported and to see how it has become an important part of Australia’s history and a powerful symbol of how many people first came to this country.

Notes:

The National Gallery of Australia’s Exhibition, called A Century of Quilts, is on in Canberra and runs from March 16th – 25th August 2024. You can find out more at https://nga.gov.au/exhibitions/a-century-of-quilts/

Patchwork Prisoners, written by Dianne Snowden and Trudy Cowley can often be bought from the Cracked and Spineless Bookshop in Hobart, Tasmania. To contact them, e-mail

crackedandspineless@outlook.com. Alternatively, it can sometimes be found second-hand at Abebooks.

If you are interested in the records of the female convicts who were transported, here is the website: https://femaleconvicts.org.au/registration/access-the-database

There are a number of arts projects about the women of The Rajah and female convicts in general.

Thanks to Sue-Ellen from New Zealand for alerting me to Roses from the Heart https://waterfordwomenscentre.com/?page_id=48 which celebrates women from Britain and Ireland transported to Australia.

And also Bern Emmerich’s work about the women of The Rajah.

https://www.portrait.gov.au/content/so-fine-bern-emmerichs

The Rajah Quilt, Picture Courtesy of the NGA, Canberra

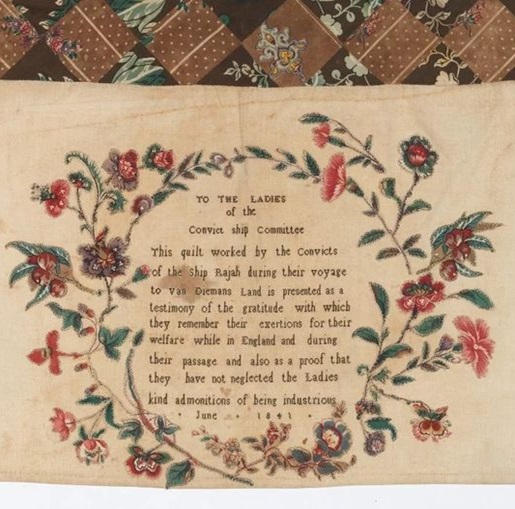

Inscription on the Rajah Quilt – Picture Courtesy of the NGA, Canberra

Simeran Maxwell with The Rajah Quilt – NGA, Canberra

Dianne Snowden

A Ship Like The Rajah, Unknown Source for Picture

Condtions On Board A Convict Ship – Picture Source Unknown

Capt. Charles Ferguson Circa 1845. Courtesy David Ferguson

Portrait of Kezia Hayter Circa 1845, Courtesy David Ferguson

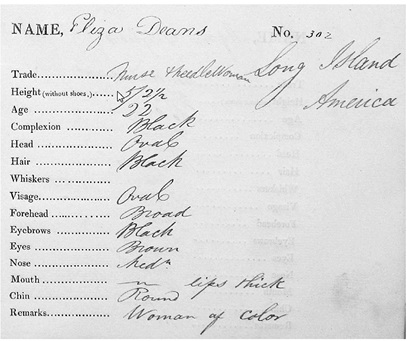

Offical description of Eliza Deans from Convict Records

Jane Burt With Her Husband James Wright, Courtesy Traralgon & District Historical Society

Script

Australia’s Convict Quilt: Something to be Proud of

JA: On April 5th 1841 a British merchant ship slipped her moorings and left the Pool of London on the tide. The Rajah was a forty-foot wooden barque made in Whitby in Yorkshire. Her cargo was human: 180 woman and ten children. She was bound for Hobart in Van Diemen’s Land in Australia and the women were being transported as convicts. There is no record that any of them ever saw Britain or Ireland again. The voyage took 105 days and in that time these women, who were poor – and had led difficult and chaotic lives – created an intricate and beautiful quilt of nearly 3,000 pieces that has become one of Australia’s most loved artefacts, an enduring symbol of its colonial history and the role its convict past has played in creating it as a nation.

Dianne: I think for a long time Australians were shy to admit, or embarrassed to admit that they had convict heritage. And there are very few tangible indications of our convict ancestry. And The Rajah Quilt is something that we can see, that we can understand and gives us a reason to be proud of our convict ancestors. And when you think about it, the fact that it was hidden in a loft in Scotland for such a long time and then reappeared, it’s a remarkable story in itself. But that makes us think that, well, you know, the convicts weren’t that bad. They could create a thing of beauty like this, and I think we all would like to have a Rajah ancestor who’d done that.

JA: Dianne Snowden is a researcher of women’s convict histories and co-author of a book called Patchwork Prisoners. She is proud to have more than 20 convicts among her direct ancestors. This episode of Haptic & Hue is about The Rajah Quilt and the women who made it, who despite their incredibly tough lives, have left us something precious and beautiful. I’m Jo Andrews, a handweaver interested in the stories textiles tell us, and the often hidden hands that make cloth and bring it into being. These tales cast a fresh light on the human story and almost always have something new to tell us about the lives of the people who work with fabric and fibre.The Rajah quilt is the only example of work completed on board a convict ship that survives – nothing else from those painful transports has surfaced, partly because for so long this was buried in shame, and also because those transported had so little to start with. This quilt’s story is an extraordinary one, as we will see, but purely as an object it still has the capacity to charm:

Dianne: It’s intricate, it’s creative. It is the work of convict women. And that in itself is rare. The colours are really vibrant. There are little birds and flowers all through it. It’s just, it’s just an amazing thing to see. And it’s still so colourful after all these years.

JA: The work Dianne and her co-author Trudy, have done on the women who were transported on The Rajah allows us to understand how it came to be made and also to see these women as individuals rather than as anonymous convicts.

Dianne: Poverty was a long-term problem in England and in Scotland after the Industrial Revolution. The women are, victims in a sense that they were victims of that, but they also had a certain amount of agency where they took their lives into their own hands

JA: Some on board The Rajah were first time offenders, others were not. The vast majority were being transported for stealing and often stealing textiles and clothing:

Dianne: And it does seem particularly unfair that they should be transported for seven years or even longer for what was really a minor offense in something we, we wouldn’t even take to court today. But overwhelmingly, they were transported for stealing for some form of theft, including picking pockets. There were a couple of cases of assault. One woman had an argument with a man and threw vitriol over him. But for the most part, it was either stealing or receiving. There’s another case of coining, so making counterfeit money. But, they were thieves.

JA: The records show that many of them were also prostitutes:

Dianne: You couldn’t be transported for prostitution. That wasn’t a crime. And a lot of the convict records, which are rich in detail, will have marked on them on the town and give the time, the length of time that the women stated that they were on the town. So, you know, six months, two years. Stealing, I think, was a form of survival. You could steal a petticoat and you could sell it off, so you’d have some money to live on for a short term. And duping gentlemen and taking away their goods was also, I think, a way of survival.

JA: It was a hand to mouth existence. One crime that comes up is stripping middle class children out alone of their clothes so they could be sold on. Jane Burt aged 15 and her sister Caroline aged 14 were convicted in Dorchester and transported for 7 years just for stealing linen from a hedge. Maria Musgrove, who is one of those whose story we can follow in this episode, stole a blanket, and other items. She was tried in the quarter sessions at Exeter where her husband explained that she’d done it because they were being pressed for the rent and he had been ill and in hospital. He pointed out that she had a five-month-old baby that she was feeding and pleaded for mercy – to no avail – she was sentenced to ten years transportation. In Scotland, however, often the courts didn’t pass a sentence of transportation unless the woman had a reputation for crime:

Dianne: The Scottish women were rarely convicted first time. And there’s a wonderful phrase in the Scottish legal system that they were convicted of larceny and habit and repute, which meant that they had reputation of being a criminal.

JA: Women like Eliza Deans aged 22 who was tried in Edinburgh and transported for stealing a pair of boots, and then there’s Rose Ford, convicted of housebreaking, tried in Glasgow and transported for 7 years. She was, at best, 13 years old. All three of her sisters were also separately transported at different times. Dianne believes there was a grim official purpose to all of this:

Dianne: It was a way of getting rid of a lot of troublesome women, you can’t find the evidence to prove that. But, you know it seems to me that that’s what was going on. And of course, we needed women in Van Diemen’s Land, or Tasmania, as, as it’s now known, because there was a huge imbalance. There was one woman to every 10 men. So we needed to do something about that. The people who’d gained land in the colony needed domestic servants. So it was another way of providing labour for the colony was to transport these women from England, Scotland Ireland, and other British colonies.

JA: But first they were imprisoned in Britain while they waited to be transported. Conditions were appalling, but not as bad as they had been nearly thirty years earlier when the Quaker reformer Elizabeth Fry visited Newgate Prison in 1813. Here are her daughters recording what she found:

Extract Fry Daughters diary.

“Nearly three hundred women with their numerous children were crowded, tried and untried, misdemounts and felons, without classification, without employment and no other superintendence than that given by a man and his son, who had charge of them by night and by day, in the same rooms, in rag and dirt, destitute of sufficient clothing, sleeping without bedding on the floor. With the proceeds of their clamorous begging when any stranger appeared among them, the prisoners purchased liquors from a regular tap in the prison. Spirit were openly drunk and the ear assailed by the most terrible language”.

JA: Mrs Fry set about changing this through the British Ladies Society for Promoting the Reformation of Female Prisoners. She advocated basic care for the women providing them with clothing and bedding and teaching them skills that might help them pursue a life away from crime, like literacy, laundry and needlework. In time her reforming eye spread to the women embarking on the long and unknown voyage to Australia, and a separate committee was set up called the Convict Ship Committee, dedicated to the moral and physical welfare of the women being transported and their children. Sewing kits and fabric were given to every woman who embarked.

Dianne: There were probably two ideas at the centre of it. One was to give them some form of religious instruction which was consistent with the Quaker reform movement. But the other was to give them something to do on the ship so they could be under control, because the last thing that you needed on a convict ship was a, a ship full of unruly women with nothing to do. And that’s when the trouble started.

JA: And these were women who had spirit and energy:

Dianne: They were unruly women for the most part. I mean, there were some who were very quiet, and wouldn’t have caused trouble, but for others that they didn’t want be there. You know, they were going to be on the other side of the world, they were going to a future, they had no idea of what it would be like. So, and under the circumstances, I think I’d be playing up a bit as well. But, giving them something to do giving them some religious instruction, whether they took that on board or not was one of the central ideas. The other thing that Elizabeth Fry really advocated was that women should be looking after women. So instead of having men on the convict ship controlling the women, there was a matron, and the matron on The Rajah was 23 years old and from a genteel family. And she was given the passage if she agreed to be matron, and she had to do some work at the other end. But she was very young. Some of these women were, you know, as I said before, quite unruly. They were rough working-class women. And to be in charge of 180 women and their children was a big ask for someone like Kezia Hayter.

JA: And the matron on board the Rajah, Kezia Hayter is central to the story of the quilt. The voyage changed her life just as surely as it changed the life of the women being transported. She was just 23 as Dianne says, and the idea of making the Rajah quilt seems to have been hers.

Dianne: Certainly, yeah. It was her project. I’m quite convinced of that. The women were given bags of patchwork squares and a whole lot of other things when they boarded the ship, that it’s a gift from the Ship Committee. And they were able to make their own quilts. But none of those have survived. And we think that The Rajah Quilt has survived because it was a presentation quilt. It was designed to be presented to someone at the end of the voyage.

JA: What also convinces Dianne that the quilt was Kezia’s project is the very genteel inscription embroidered at the quilt’s centre.

Inscription

“To the Ladies of the Convict Ship Committee. This quilt, worked by the convicts of the ship Rajah during their voyage to Van Diemen’s Land is presented as a testimony of the gratitude with which they remember their exertions for their welfare while in England and during their passage and also as proof that they have not neglected the ladies kind admonitions of being industrious. June 1841”.

JA: The quilt is enormously complex. It is huge, over three meters square – that’s ten feet by ten feet, and it is made up of nearly 3,000 pieces. It should properly be described as a quilt top as it has never been made up into a covering. Simeran Maxwell who is the curator at Australia’s National Gallery has been preparing it for display:

Simeran: So when you look at something like this and you look at the detail and you think about the conditions that the women experienced, you sort of are in awe. And for me, I always love the detail. I love to see the juxtaposition of fabric choices, for anyone who hasn’t really, really looked at something like a, a beautiful quilt, you just go, oh, yeah, it’s sort of, it’s sort of like, just throw it up, actually, to put something that looks just so casual together is incredibly difficult. So, to match a pattern with another pattern that works visually and doesn’t look too matchy, matchy but the, the two pieces really pop, and you really see them both is incredibly hard. And you see that in this quilt with the borders. So, it’s a medallion, a pieced medallion quilt, essentially. The central part is a embroidery purse, and there’s flowers and birds, and then there’s four larger birds, and then there’s a square, and then there’s applique flowers in a border, and then there’s 12 more borders, and then there are flowers around the edge. And there’s also an inscription. We know that certain parts were done with one, one hand. The more complicated areas would’ve been given to somebody who had experience in embroidery. And to create a cohesive look. But then as you go through the border patterns you start to see some stitching that is not as tight as others, or not as even as others. Some of those seams are really, really small, which again, is, is kind of fabulous.

JA: So the work of creating the quilt was most likely overseen by Kezia Hayter, but whose hands were involved? That’s the question Dianne and her co-author set out to answer with their research. They can’t definitively provide the names, but they have gathered a list of 45 women amongst the 180 who could have worked on the quilt because they had the right skills.

Dianne: We knew from what we’d been told by the National Gallery, that it was the work of many hands, and we wanted to find out who they were. So we ended up with quite a list of people who had sewing skills, very basic sewing skills to dress making skills. And we’ve listed those in the book, and there’s quite a few, but we can’t categorically say which ones made the quilt. We did have someone come up to us when we were talking once about the blood stains from pricked fingers on the quilt, whether she could get her DNA from that to prove that her ancestor had actually made the quilt. But that came to nothing surprisingly. The quilts been here once in 2004. I saw it again in 2011 in Melbourne. And I’m always amazed at the vibrancy of the quilt. You think after all of this time, it would’ve lost some of its colour. And its brilliance, but it hasn’t. It’s the most amazing textile I’ve ever seen.

JA: Our boot stealer from Edinburgh, Eliza Deans, is one of those who had the skills to have worked on the quilt. She was 22 years old, and she gave her trade as nurse and needlewoman. And then there is Maria Musgrove who stated her trade as a dressmaker. Maria had left her husband Thomas behind, and by the time she was transported her little daughter Mary Ann was two. We can’t prove these two women were quilt makers but we know they were skilled needlewomen. They certainly weren’t the only ones who worked on this project.

Dianne: Some of the pieces are done with great skill, and they’re exquisite. And there are other bits where, or originally people thought that the the patches had faded, but in fact, they were inside out. And when you think about the conditions on the ship, it’s not going to be bright light, you know, people were working under difficult conditions. It’s, it’s really, it’s, it’s astounding. It was actually finished and created, presented and survived. So it’s you can see the differences in the skill level in, in the patches and the embroidery on the quilt.

JA: Another question is why did they do it? Here’s Simeran Maxwell again:

Simeran: We know that there were 400 different types of fabric used in the quilt, and that most of these were new. There are makers’ marks on some of them. Because it’s an unlined quilt, we can also see the reverse. We also know how much fabric and materials that the women were given before they boarded the boat. So the idea of the quilt is very unusual. Women did do make things on board. What, what else would you do for three months? But it was usually things that they kept or that they sold along the way to make some money so that when they arrived at their destination, they wouldn’t be destitute. They would have some something to start with. Whereas these women put all their energy into making something to prove to the Lieutenant Governor’s wife that they were somebody, they, they weren’t just useless, the, the hope was that she would look favourably on the group and then help, help them.

JA: The quilt was finished almost a month before The Rajah arrived in Hobart in modern day Tasmania and it was presented to Lady Franklin, wife of the Lieutenant Governor, Sir John Franklin. She seems to have made very little of it and it rapidly disappears from sight for over 140 years. But because they were in the charge of the British state, the women do not disappear: they are processed and detailed, which is how we learn that Eliza Deans, although from Edinburgh, was a woman of colour and so was her ship-mate, Jane Johnson.

Dianne: So what was happening in the 18 hundreds during the convict era was that anyone who was in a British colony could be transported to Van Dieman’s land, or one of the other places like Bermuda. People from Hong Kong, for example, the West Indies. But these women were from Scotland. The two women of colour on The Rajah were actually from Scotland. The convict records are really rich. So we have a, a conduct record, which is a record of what the women did and where they were after they arrived in the colony. We have a description list, which is quite detailed, and we have an indent, which is, which came with the women and gives information about living family. So they’re really rich records for historical research. The description list for Jane Johnson and the other woman of colour, Eliza Deans, described them as having a black complexion, black hair, brown eyes. So, you know, they would’ve stood out in the colony.

JA: Eliza was born in America and gives her birth place as Long Island. Her father is thought to have been a planter from the West Indies, her mother is unknown. When Eliza arrived in Australia, she was assigned first as a domestic servant to the clergyman, the Reverend Mr Lillie of Hobart. Her ship mate and likely fellow quilter, Maria Musgrove, was not so lucky. Mary Ann was quickly removed from her.

Dianne: When they got to Van Dieman’s Land, the children were taken from their mothers and placed into an institution called the Orphan School. Now, it wasn’t a school for orphans, but it was a school, an institution for destitute children. And it’s unlikely that the women knew that the children were going to be taken away when they got to, to Hobart. And I find that really heart-breaking.

JA: Conditions were dreadful and without their mothers to care for them, many quickly died. Mary Ann lost her life at the age of 3 succumbing horribly to gangrene of the mouth. Ten children made the passage with their mothers on the Rajah, but many others were left behind.

Dianne: They had to choose which ones to bring. So they would take perhaps the two youngest ones. They left children behind, and it’s unlikely that they were ever reunited with those children that were left behind. So it’s a heart-breaking story.

JA: It’s known that the women on The Rajah left 90 children behind when they sailed and they never saw them again. But for some the voyage was a way to re-join their family. Mary Sullivan, who had pawned a jacket that didn’t belong to her, said she’d done it because she wanted to join her husband, Michael who had been transported in 1837. They were eventually re-united and in 1850 left Australia together for San Francisco.

Dianne: It was quite common for families to be transported either on the same ship or women on the same ship or later ships. So, there’s an entire family, and it is an Irish example. The father was transported. He applied for his wife to come out under the convict Family reunification scheme. She couldn’t wait that long. So, she committed a crime and came out. And all in all, there were eight members of that particular family who ended up in Van Dieman’s land. Yeah. And that was the tip of the iceberg. I did my PhD thesis on women who were transported from Ireland after the famine. And they stated that they deliberately committed the crime in order to be transported. So, they’d set fire to something and stand there and wait till they were arrested. And some of them gave reasons, like I did it to better my conditions. I did it to join my father. I wanted to find my mother. So, there are heart-breaking stories about the reasons women committed crime.

JA: The journey to Tasmania took all of the woman to a different land and changed their lives forever. For Kezia Hayter, the young matron who had organised the making of the quilt, the voyage marked a turning point in her life.

Dianne: Kezia Hayter was taken under Lady Franklin’s wing, and she was given tasks to do such as visiting the women where they were housed. We think that the quilt was presented to the Franklins. We think that it then went back to Scotland, because there’s another side of Kezia’s story in that she fell in love with the ship’s captain and married him, and he took The Rajah back for another voyage while she stayed here. And the Franklins in 1843 left on The Rajah. So, we think it went back with the Franklins. There’s no evidence of it being here, and there’s a missing link between it going back to England and ending up in Scotland, and it’s probably Captain Ferguson had something to do with it, but I can’t find the evidence. But the yes, the young refined, gentle matron of all of these unruly women married the ship’s captain.

JA: No-one knows what became of the quilt, until quite unexpectedly it turned up in 1987 more than 145 years later.

Dianne: And it’s found in a loft in Scotland, and it would’ve been so easy for the people that found it to say, what’s this bit of rubbish? Now let’s get rid of that. We don’t need it. But miraculously, it was saved and, and came back to Australia, and it’s in the National Gallery.

JA: Where it is cared for by Simeran Maxwell and her team:

Simeran: And it looks like it was never washed, which is fantastic, so the materials that were used by the prisoners, they reflect the printing industry at the time. And a lot of the printing techniques, if they had been exposed to light and also washed against one another and there are nearly 3000 pieces on, on the textile, then you would’ve got bleeding, you would’ve got a lot of fading. And that’s why we don’t have it on display very often, but I mean, not because of the bleeding, because our textile conservators know what they’re doing when they’re cleaning it, but the fading is a real concern. So the fact that it was in somebody’s, you know, living closet is a blessing in terms of the, the condition that it now appears in. And the fact that when, when we are able to get it out that people can really see that very clear, crisp snapshot of what textiles would’ve looked like well over a hundred years ago.

JA The Rajah Quilt is the National Gallery’s most requested work of art and Simeran knows it will be a big draw at the new exhibition.

Simeran: And it, it comes out so rarely because it’s sheer size. We’ve had to build this purpose-built showcase, which is enormous and takes up quite a lot of the gallery space. And, you know, from the moment I started working on this show, you know, we always have budgetary issues. It’s the sort of never-ending discussion. And I said, you know, like, we can juggle any work in this show. We can make, make it work. This is the only one that absolutely has to, has to be on display. And of course, it’s the one that’s <laugh> caused the most problems because of the purpose-built showcase and the special lighting and the glass and the size of it.

JA: For the women who stitched it – it would be almost incomprehensible that their quilt should be much loved and in Australia’s National Gallery. Although all of them eventually won their freedom by servitude, their lives were never easy. Maria Musgrove gave birth to two more children – one of whom seems to have survived. Before she was freed she was convicted of misconduct in having a bottle of wine concealed for which she could not satisfactorily account and of being in a man’s bedroom undressed for an improper purpose. Devoid of family and support networks, it seems she was never able to establish a stable life but survived on the margins. She died in 1885 aged 71 in the New Town Pauper Establishment in Hobart, which is what the Orphan School where her daughter had been placed all those years before had become. Like her little daughter she is buried there.

Eliza Deans’ sentence was extended by three years for breaking various rules. When she was finally free she left Tasmania for Victoria on the Australian mainland. She married twice – the second time to the widower of one of her shipmates. When she was 60 she was admitted to the Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum in Melbourne where she died six days later of a disease of the brain. And Jane Burt, the girl who did nothing but steal some laundry from a hedge in Dorset, married and had seven children. She lived to the age of 90 and she is one of the few women from The Rajah of whom we have a photograph. When she died in 1911, her obituary in her local newspaper described her as ‘a bright and cheerful old lady….very highly esteemed by all who knew her”.

Dianne: I have yet to see an obituary that says, I came out on the convict ship and then I did. Well men are referred to as old hands and quite often we’ll find that the convict women are pioneers of the district and, and much loved, or, you know, a much-loved midwife if they went into midwifery, those sorts of stories. But it, it would’ve been a very tough thing for my grandparents, great-grandparents to admit to their convict ancestry. And all of my grand, all of my grandparents were descended from convicts, but it was never discussed. The other thing about women when they went, served their sentence is that during the time they were under sentence, they were housed, they were fed, they were clothed. After their seven years, or whatever their term was, was up, they were on their own hands, and they had to find a way of living. Marriage was encouraged for all sorts of reasons. But even that didn’t provide a secure income in, in a lot of cases. And desertion was common, particularly at the time of the gold rushes in Victoria. So, it, it could be really tough.

JA: But what was created on The Rajah all those years ago in such difficult conditions has become an important icon for part of Australian society – here’s Simeran Maxwell:

Simeran: In a sort of, I guess a similar way to some people in America who feel, you know, that connection to those people who came out on the Mayflower, the people who came out as convicts, they didn’t choose to come here, they were sent. There is that connection with Australia with, with the development of White Australia within history. So, for many people, this idea is quite embedded. I also think that quilting communities are very dedicated. These women worked so hard and they were not given the recognition. But there is a huge part of particularly our women visitors who are aware of how skilled these sort of things are and how beautiful they are. So, they want to come and see them.

JA: Migration, forced or voluntary, is always hard, we leave part of ourselves behind and carry forward our hope. These women arrived in Australia as convicts with nothing, and even though they lived their lives in hardship and obscurity they managed to make something skilful and beautiful – something that survives to this day and stands for all us who have ever had to start a new life somewhere else, which gives the quilt a global resonance far beyond Australia.

Dianne: And at the end of the book, I wrote that the journey of writing the book was like making a quilt, you know, a little piece here and a little piece there until you’ve got a whole. And I think, I hope we’ve done justice to the stories of the women and their children.

JA: Thank you to Dianne Snowden and Simeran Maxwell, without their knowledge and scholarship this episode would not have been possible. The extract from The Fry Daughters’ Diary and the Quilt Inscription were read by Constance Wookey. Thanks also to listeners, Jo Davison, Debra Mika and Pat Scholz in Tasmania all of whom separately suggested this story should be told: They were right! Haptic & Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and edited and produced by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast independent, and free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you extra content every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted by Bill Taylor and me, where we cover a whole range of different textile news and topics. You can find out more about this episode, and see pictures of the Rajah Quilt and some of the women who travelled as convicts on the ship at www.hapticandhue.com/listen-series-6 We will be back next month with a new episode about feed sacks, yes these are the stuff of American mythology – the frugal fabric of the Depression, but there is so much more to their story than that. Join us next time on the first Thursday of the month and until then – thank you for listening and enjoy whatever making you are doing.