Episode #49

Jo Andrews

This episode uncovers the secrets of the 14th century cloth stainers which lie in a pocket-sized book, transcribed more than six hundred years ago, by monks at Gloucester Cathedral. The little book contains 30 recipes for preparing cloth and special water-based colours to permanently paint and block print wool and linen. Haptic & Hue took a trip to Gloucester Cathedral to explore the lost world of medieval textiles.

Notes:

The Gloucester Manuscript is kept in the Library of Gloucester Cathedral. You can find out more about the Cathedral as a whole at https://gloucestercathedral.org.uk/ and about the Library and the manuscript at https://gloucestercathedral.org.uk/cathedral/heritage/archive-and-library You can follow the Cathedral at https://www.instagram.com/gloucestercathedral/

Mark Clarke’s website is at https://www.clericus.org/ where he gives details of his research and access to some more recipes from different books.

Jorge Kelman is on Facebook as the Guild of Saynt Luke where you can get information about the workshops he runs and the cloths and stains he produces. https://www.facebook.com/23newthings/

Rebecca Phillips, Gloucester Cathedral Archivist

Gloucester Cathedral Library

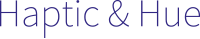

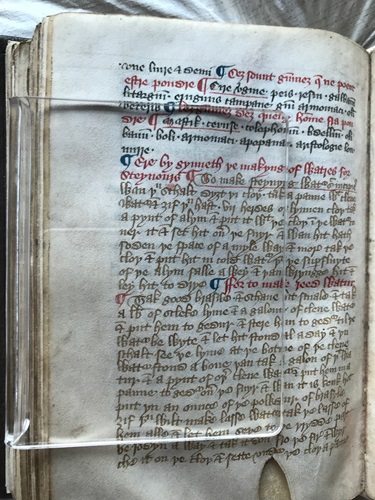

The Gloucester Manuscript

Mark Clark

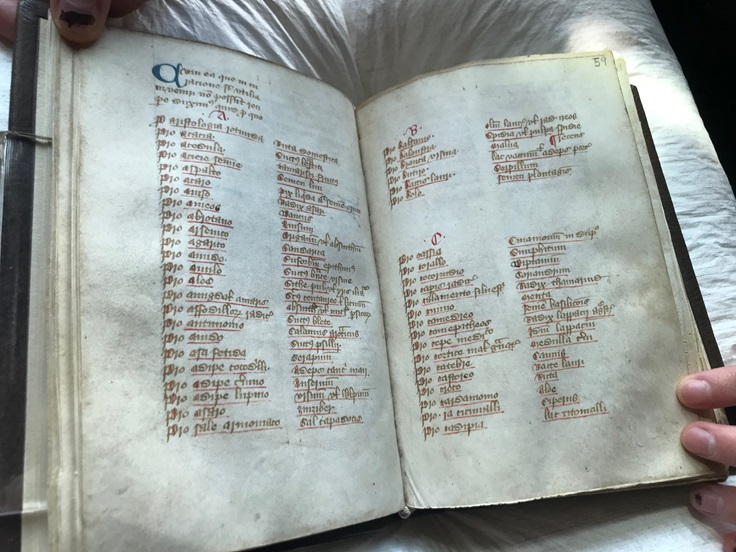

Cloth stained by Jorge

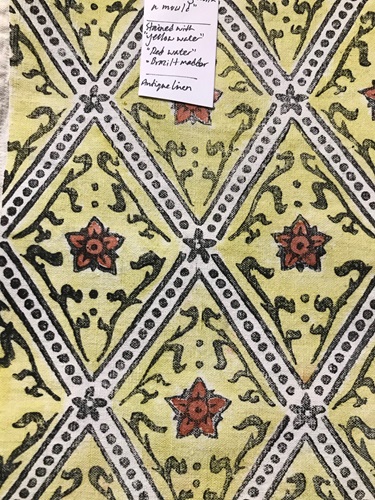

Cloth stamped and stained by Jorge

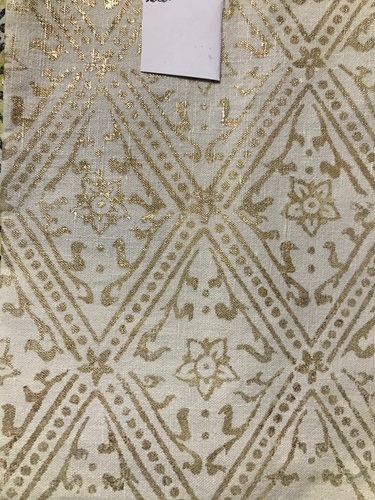

Gilded cloth made by Jorge

Jorge Kelman

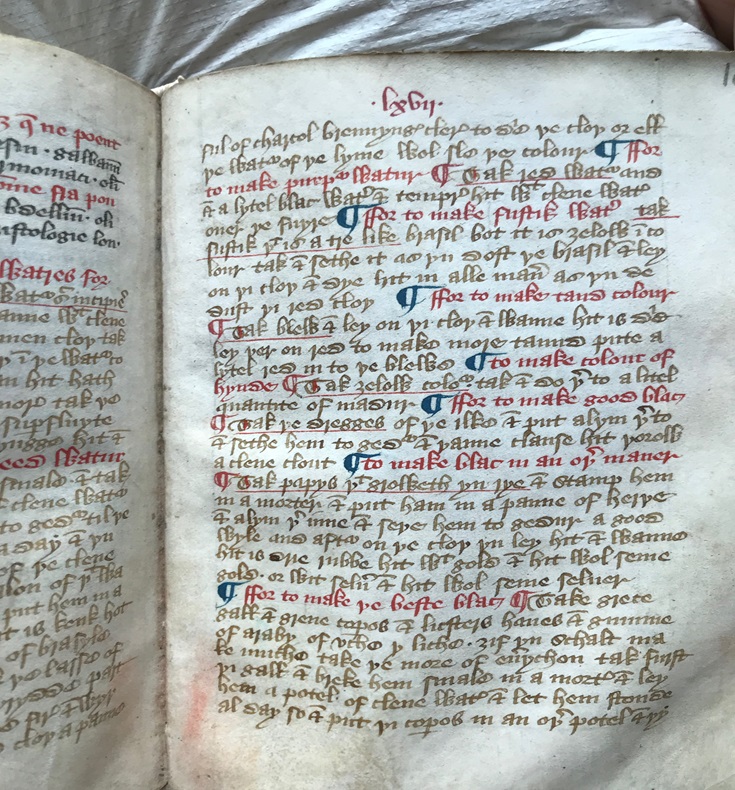

Staining recipes from the Manuscript

Staining recipes from the Manuscript

Painted front of the Hessett Burse

Back of the Hessett Burse

Script

The Forgotten Medieval Craft of Cloth Staining

JA: Gloucester Cathedral is more than 900 years old. It stands not far from the River Severn in the West of England. It’s honey coloured stone has weathered a great deal of history, and its share of celebration and tragedy, of death, war, famine and glory. The building we see today was beginning to take shape in the late 1300s, but even so it would have seemed a very different place then. It was home to a Benedictine Monastery with a number of monks whose role was to care for the spiritual and sometimes the earthly needs of the people. At some stage in the late 1300s the Gloucester monks, working in the open cloisters, transcribed hundreds of recipes, charms and spells covering almost every aspect of life at the time and bound them into a small book:

Rebecca Phillips: Unfortunately, my monastic predecessors never thought to write down on it the exact date when they’re copying it out. I love it when they do. Sometimes you get these little wondrous spits in medieval books where they actually put the date that they’ve been copying because kind of finally got here by my birthday, or unfortunately no margin a like that for us in this. But we can date the content from the fact that that chronicle stops at a certain date and they haven’t added to it. And that stops in the 1390s. So, we think it’s not been added to after the 1390s.

JA: That’s Rebecca Phillips who is Gloucester Cathedral’s Archivist. The book she takes care of is immensely important not because its beautifully illustrated or written – it isn’t, but because it gives us a glimpse into the lives of people of that time, how they coped, what they thought was important, how they celebrated and mourned. In a sense the book is a manual of how they lived, and it allows us that rare thing – to get a little closer to who our ancestors really were as people and the world they actually lived in.

Rebecca: So, we have no accounts, we have no minute books, we have no records of decisions, we have no lovely letters from monks to each other. We’ve lost almost everything that tells us about the life apart from this, this lovely little treasure for us. it’s the book that I would kind of, I would cry if we ever lost. I would cry about others, but this is the one that would make me sad to my soul if we ever lost it.

JA: Welcome to Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews. I’m a handweaver, interested in what cloth tells us about ourselves and our communities. Often the stories and information that textiles give us are ignored and we lose a whole dimension of human experience. Frequently the hands that create the textiles we treasure remain unknown and anonymous or the fabrics themselves have perished over the years and can no longer bear witness.

One of the important things that the Gloucester manuscript contains is 30 recipes for stains, you might think on first reading that these were dyes – but they were not. They were something else altogether – a forgotten textile craft that provided much of the colour, joy and backdrop to medieval life. Stains were water-based and sometimes oil-based colours used to paint and stamp textiles, and its only recently that we have begun to understand how important these were, partly because almost all of the stained cloth has perished and the recipes have only survived in books like the Gloucester Manuscript. Mark Clarke who translated the recipes in the Gloucester Book into modern English, is an Associate Professor of Technical Art History. He is very clear about the difference between staining and dyeing cloth.

Mark Clarke: Staining is different from dyeing. Dyeing is where you use a solid colour and you get the whole cloth and you immerse it in a vat and the whole thing comes out the same colour on both sides all over. Staining meant making figurative designs on cloth using a water-based medium. And that was the essential, it’s taken a while to unpick this. That’s not written anywhere as a definition. I’ve had to figure that out by looking at the recipes and looking at the law cases and the, the running battles in the streets between the painters and stainers over this, the painters and stainers fought for, for years until 15. Oh, well, 1502 I think they combined the two guilds in London.

JA: The point about stained cloth was that compared to tapestry or embroidery it was quick to make. It was painted onto hand woven linen or woollen cloth and it would have been used to provide colour in the poorest home, to the grandest palace. Every important ceremony, funeral, pageant, procession, masque, tilt, or tournament required banners, flags, pennants, or scenery. And before the Reformation it would have been ubiquitous in England’s brightly coloured churches, abbeys and monasteries. Here’s Mark Clarke again:

Mark: They were a truly, I don’t want to say democratic, that’s completely the wrong word. They were everywhere. So, we have wills and we have inventories and such like documents. And they show us that there were stained cloths in the royal palaces. There were stained cloths in the rooms of people described as servants and everything in between. They were in churches, they were in cathedrals, they were in lots and lots and lots of domestic settings. They were used as banners outside shops. They were used. If you have a, suddenly somebody dies, some big, big name person dies. You don’t have time to make a tapestry cover for his coffin. It’s not going to happen in time. Tapestries take months, years to make a decent sized tapestry. But you can knock up a stained cloth in a couple of days. They’re excellent for ephemeral things. So, say the king of somewhere is coming to visit, or the bishop of somewhere is coming to visit, or the king of your own country is coming to visit and you don’t have a huge amount of warning for this man coming. You need to line the streets with banners. You need tabards for people. You need tabards for the heralds. You need tabards for anybody who’s remotely important. You may, maybe you need little tabards for the, for the choir to smarten them up a bit. You perhaps want fake scenery. You want theatrical style scenery for masques in the sense of theatrical performances. You’ll perhaps build a mock castle entrance over the main street into town. You will build pavilions, you will have flags, you will have banners. And all these need to be made in a huge hurry. And there are records of these where somebody goes right to pay so and so to make, you know, some implausibly, large number of banners and he’ll knock these things off in, in a week. So, if you’re perhaps going to have a great meeting of, of, you know, major forces in a field somewhere. I mean, the Field of the Cloth of Gold is an example that springs to mind that’s famous because it was more dramatic. It was actually cloth of gold. But for pretty much everything else, they’d be stained all these tents and these pavilions would be stained. I’m absolutely convinced of this.

JA: And Mark says that people would have used them widely in their homes as a form of medieval interior decoration:

Mark: People would’ve had them for curtains to hang over the door. People would’ve had them to hang over the walls just to make the place cozier. And, of course, they keep the drafts out and they help with the damp, but mainly they just look nice. And they’re giving you a sort of an a, a double- glazing effect on your wall, you know, where the, the cloth is holding you. Lots and lots and lots of houses would’ve had these, great to a larger or smaller ones, bed hangings, testers over the bed cushions, bed covers and so on. Enormous amounts, there would’ve been acres of this stuff. Absolutely. Huge, huge, huge quantities of it.

JA This knowledge upends my view of this time as visually dull, especially for poorer people. Life was certainly hard and I had thought that to our eyes it would also have been relatively plain, bare and colourless. But it seems medieval interior decoration was more complex than I thought: because of the stainers, the age was much brighter and more saturated than we imagine.

Mark Clarke: So staining, you can do just patterns, simple repeats, which again is where the block printing comes in. You can stain with moulds, stain with blocks. So, you get a simple repeat or you can do pictures of things. Now you could be just painting simple designs of birds and flowers, or you can paint, sorry, you can stain mythological scenes. Very popular battle scenes, very popular. And again, these inventories and such, like will say, a stained cloth depicting St Cecilia and musical instruments say or depicting such and such, you know, King Alexander the Great and his generals or whatever. So, so you can actually, any, the best way to imagine what was on stained cloths is to look at tapestries. So, whatever was done in a tapestry was done in staining. They’re essentially the same pictorially, the same range of things you’d find in a tapestry, which could just be some birds or some flowers or some vine leaves on a cushion. Or it could be the glorious triumph of the current king against, you know, crushing his enemies on a massive wall thing. And exactly the same range of pictures of, of imagery. It was enormously fast. And, and these things were done on the floor. You lay them on the floor on a mat of rushes or straw, you pin the cloth in place using thorns. And then you walk all over and you slop this, this, this stain on. You really pour it on. And so the excess can run through to the, the straw underneath. So, you are really working fast and you’re putting on one coat on whack, whack, whack, whack, whack. Perhaps you’re using stencils. A lot of stencilling would’ve gone on. and you could knock one of these things off in a day or two. Whereas, as I say, with a tapestry, you’re looking at months to make something the same size.

JA: Mark knows from his study of documents and manuscripts that England and Flanders were centres of cloth staining and that it was also happening in Spain and probably Italy. But one of the reasons our knowledge of this is so poor is that so little of it survives. This was everyday stuff, it wasn’t elite or valuable – it was the medieval wallpaper of life and it rotted, got damp became unfashionable and was thrown out. Jorge Kelman is a practical researcher who specialises in experimenting with old staining techniques.

Jorge Kelman: I think that, the focus on historical art, has been the, the panels, the high-end stuff, the high society things that we see in museums. So, cloth painting probably seems to be much more a craft and, and less arts-based. And I think that’s partly prejudice also because not a lot of it survives at the domestic level. So, it is lack of physical visibility might be something to do with that. I think it’s special for me because I’m really interested <laugh>, it might not be special to most people who go, oh, it’s just painting on cloth. Because there are a lot of things that come up from doing this rather than simply the, the act of painting on cloth.

JA: Jorge says that the recipes in the Gloucester Book can produce rich and deep colours.

Jorge: Oh, certainly, they are bright colours. I’ve worked on most of those. And the, the Brazil reds are bright red. The welds are bright yellow. The, the greens can be quite vivid depending how you mix the colours. And the blacks can be quite dense. So yes, there’s a lot more brightness to the world than we would probably imagine. But I think the key issue is that they’re not the brightest colours that could be used. We we’re not talking about the mineral blues, the, the Ultra Marines and Azurites. So they, they work differently. But in terms of the, the human need for decoration and colour, it certainly is, is there with the, with the recipes that we have. Yeah, they’re very bright indeed. Even though they fade eventually, they, they’re, you know, quite stunning in some cases.

JA: Jorge has made up a number of the staining recipes from the Gloucester manuscript – and a word of warning – we are talking about medieval colouring processes – you might want to finish your food first:

Jorge: There is a really lovely, I say lovely guardedly. So, it’s to make a red, scarlet water. So, you take urine, essentially fresh urine, and you seethe it over the fire. And when it’s hot, you put in your powder of Brazilwood and you seethe it until you’ve reduced it by half.

Jo: Does seizing mean boiling?

Jorge: Yes seethe, S-E-E-T-H-E-I think. Yeah, So they, call it sothern, sothern. So yeah, boil it until it’s until it’s reduced in half. Then put in alum, stir it, take it from the fire, let it cool down. And then you put it in a glazed vessel for at least seven days, if not more, before you use it, it’s very clear about it, before you use it, and it can last a year. And the cautionary tale is do not decant hot or warm urine red into a bottle when your children are running loose outside the workshop and they startle you, and then you spill it everywhere, everywhere.

JA: But it once you manage to do this successfully it gives you a wonderful deep colour.

Jorge: Now, apart from the cautionary tale, the really interesting thing I think about this particular recipe is that you, you get this really lovely deep red because you have the urine, the alum. So, urine gives it a bit of alkalinity. So, Brazilwood usually when I cook up as a water, it’s a very bright cherry red, and it’s got a warm, warm red when it, when the pH rises, it goes to the blue part of the spectrum. So, it starts to be a much deeper colder red. So, you get that on top, and it’s lovely. And it’s, it’s a very, it’s a viable red. It’s a great colour, but what you get at the bottom is an extra, and it isn’t mentioned in the recipes. And at the bottom you have a precipitate, which is as a result of the alum reacting with the alkalinity of the, the urine. And then some of that colour that drops out is a solid colour. It’s used effectively as a pigment. And that can be used to glaze over gold. And it can be also used to boost up colours that you paint on. So, you might have painted with some red lead or, or vermillion. And then you can use these lakes to add increased vibrancy.

JA: Brazilwood came, confusing, from India and South East Asia – from the mid 1300 onwards it arrived in Europe in blocks and was then rasped into a powdered form and was used for dyeing. Jorge has also found unexpected combinations of materials:

Jorge: So, to make a purple water, take red water, that would be the Brazil red and a little black water. And the black water is made with essentially oak gall ink, it’s the residues of oak gall ink cooked up with a bit of alum, and turned into a black water. Now, we rightly would assume that you make purple by mixing red and blue together, and that’s you know, a standard thing. We know that. But when you mix the black, this ink black, it gives a purple, not a vibrant violet purple, but a, it’s on the purple spectrum of things. And that’s unexpected. I just thought it was one of these, oh no, they’ve just got that wrong. But actually it, it is, it’s, it’s a respectable cheap purple that is interesting. Because It’s not what I expected the colour to be. I didn’t believe it. Basically, I just saw this, I thought, no, that’s not how you make purple. But evidently it is. It’s a, it’s another viable colour. I quite like the gilding, laying gold on cloth because when you lay gold and silver onto cloth, it contrasts very greatly with the colours that you lay down. So that, it’s quite nice to see those aesthetics at play. And, and to imagine that somebody’s house in the 15th century, you know, that could afford it, has a, a, a nice glittering cloth that emulates woven cloth, but shines and glitters, which it does, I think they’re all really interesting. But yeah, the urine, the purple and the gold would be my favourites.

JA: What Jorge has done isn’t easy and it has taken years of trial and error. One reason is that the Gloucester Manuscript and other books of recipes like it are full of mistakes, often they leave out vital steps, sometimes the steps that would have seemed obvious to the people of the day, and then there are the puzzling instructions to the modern ear. Here Mark Clarke reads from a recipe in written Middle English at the beginning of the section where it explains how to prepare cloth for staining.

Mark: Here beginneth the making of water for stainers. To make staining water one, thou shall dip thy cloth, take a panne with clene water and if thy has eight yards of linen cloth, take a pint of alum and put it with the cloth in the water, cover it and set it over the fire. And when it has sothern the space of a mile way and more, take the cloth and put it in cold water that the super fluidity of the alum fall away. And then wring it and lay it to dry. A mile way means how long it takes you to walk a mile. So, so 15 minutes, thereabouts.

JA: Indeed, how do you calculate time in an easy way with no watches or clocks? Another instruction, sometimes given in an old recipes, was to do something, like boiling it, or stirring it for the time it took to say the Lords prayer. There are a small number of stained cloths that survive in European museums, mostly they are grand pieces, but one chance survivor is much more humble: Here’s Jorge.

Jorge Kelman: We know that there’s a, a thing called the Hessett Burse, which is a small painted cloth bag to hold the consecrated host. And it comes from a, a church in Suffolk, Hessett, but it’s now at the British Museum in store, and it’s beautifully painted. It is, has gold leaf, silver leaf. It’s executed with great skill that only survives by luck because it’s a local parish church.

JA: The Hessett Burse dates from the late 1200s or early 1300s hundreds and is a small envelope like piece of cloth painted with the face of Jesus on one side and on the reverse, the Lamb of God. It was found at the bottom of a Parish chest in the Victorian era.

Jorge has made some of these beautiful stained cloths for Haptic & Hue and we will be giving them away to Friends of Haptic & Hue later this month. Mostly these stains were painted or stamped onto woven linen and wool as these were cheapest and most easily turned out, and this episode is about the stainers, but, I do wonder about all the growers, spinners and weavers of linen and wool who were producing huge quantities of fabric to feed this industry.

Today the Gloucester Manuscript lives above the Cathedral’s Song School in a hidden space that was built in the 1400s as the Library. You climb the creaking stairs and open the heavy door on a room that is every bit as beautiful as you might imagine, with leaded glass windows, ancient roof beams and thousands of books and manuscripts lining the old stone walls. The Manuscript is not just a book of Staining Recipes, it contains all manner of other charms, snippets of information and practical knowledge that you might need in the late 1300s. It begins with a history of what was then St Peters Abbey, which is why Rebecca Phillips the Cathedral Archivist believes the book was made at Gloucester.

Rebecca: So we know it must have been made for us. There’s, there’s no one else who bothers writing the history of Gloucester Abbey apart from Gloucester Abbey. But certainly, by the Dissolution it isn’t here anymore. We don’t know quite whose hands it goes into. No one keeps a record of who takes anything away from here when Henry closes the Abbey.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries – that great upheaval in English life – Henry the Eighth’s famous break with the Roman Catholic Church over its refusal to allow him to divorce his first wife and marry his second – came after 1534. As England transferred over to its new Anglican faith, Henry and his men sacked and confiscated the wealth and possessions of nearly every monastery and religious house in the country. For hundreds of years the little book disappeared and seemed lost forever, but then something incredible happened:

Rebecca: But by the 1870s it is rediscovered, and it’s rediscovered in a Berlin book sellers. And as soon as the, the Cathedral finds out about it, we send someone out there with a big pile of marks to go and buy it, to bring it back home. So, it’s been back here in the Cathedral for about 150 years now. And it’s treasured as one of our, our very few artifacts from before the Dissolution because almost everything else pre-dissolution we lose. Because of course everything was, was part of a Catholic Abbey and it’s then made into a Protestant cathedral, an Anglican cathedral, and therefore all of that, that Catholic objects, Objet D’Art, all of the knowledge that was would’ve been collected here in this library. All of that passes away and we don’t quite know what happens to most of it. We can only trace the little bits that we find popping up now elsewhere. But we know nothing of maybe the textile culture apart from the knowledge captured in this book.

JA: The book is written in a mix of Latin, Middle English – the kind of English Geoffrey Chaucer wrote in and there is even a section in old Welsh:

Rebecca: And I suppose it’s one of the reasons I find it so lovely is because it’s so full of practical knowledge. It actually shows say in this the section we’ve got here, all these practical knowledges. We’ve got their knowledge of plants, we’ve got their knowledge of medicine, we’ve got random little bits of knowledge that we’re only just starting to kind of scratch at the surface of, because we’re just working our way through and trying to translate from Latin. Many of the, the recipes and the, the collected knowledge in here and finding that we’ve got, the one we found so far is a recipe for gingerbread, but we haven’t yet translated it to check that it’s safe for human consumption. So, we can’t share it without kind of a very strong kind of health and safety label saying don’t try this at home yet. And we’ve also got recipes in there for things like how to write on a knife blade, which just completely kind of surprised us when we discovered those tucked away in there.

JA: The book, towards the end, also contains a good deal of medical information and at that time it was part of the duty of the monks to tend to the sick. Rebecca thinks that this book may have been made to travel with:

Rebecca: It feels like this is a book that the monks made so that they could carry with them everything that they needed to kind of be that connection back to, to Gloucester Abbey whenever they were going out, maybe to a daughter cell, maybe even to to other sick individuals or something like that. So, this is a period when leper hospitals are not unknown. So actually, is it something they could carry with them when they’re going to their leper cells outside? It’s got that mixture of kind of, this is why it’s important that you are part of us, but also here’s all the knowledge that you might find useful to you whilst you’re traveling. And it is, I mean it sounds blase to say it’s pocket sized, but the pages are, are kind of not that much larger than maybe a modern Kindle screen or a modern paperback really, aren’t they? The actual kind of page size it thick. It’s a good three or four inches thick, but it would fit in a, in a kind of, in a parcel and easily within the pockets I’m wearing today. The only other versions of that history that we know of don’t have all this practical knowledge and they are much bigger books with much more decoration and they are all about saying, we are important and this story is important and they’re probably made to put on altars or on lecterns and showing off. This is about being taken with you, about traveling with you, about carrying that information of kind of connection and of use as they go.

JA: The Book also still has puzzles and mysteries to give up.

Rebecca: So, I I first met this book on probably my second or third day here at the library seven years ago, and was flicking through and was looking at the, the limited catalogue we had for it at the time. And in amongst that catalogue it said about this charm, this curse. So I turned to that and it’s the page before it that gripped me because as I was trying to find it suddenly stood out from the text was the line that said for, to help a woman that is with child. And it just jumped out me because I was reading it and thinking, but this is a group of monastic males in an enclosed order. What are they doing getting involved in childbirth? And I’m still not a hundred percent certain of that answer. Is it the very start of medicalization, of childbirth? Is it that they are only ever called in when the midwives can’t help and that’s why it’s got a charm in there? Is it much, much more? But in amongst the charm for that one, it includes four lines out of five of one of those palindrome squares, which are, we know of a, a carved version of this from Roman times down at Cirencester that’s in the Corinium museum today. But it’s the square that starts Sarto, Arepo, Tenet, Opera, Rotas. And they’ve written all four of those five lines out and the only one they’ve missed out is opera. So who knows why. And I don’t think as yet academics have agreed entirely on what the meaning of that square is. When they find it. They just recognize that it was, even from Roman times, it was being recognized as a, a grid of power as somehow kind of special that it can be read in every direction and it works in every direction. And that somehow it calls power into, into play. And the fact that it’s been included alongside a load of saints’ names and then it’s being used to help women in a male monastic culture is just it, it’s got so many layers of mystery there for me. I never get bored of that mystery.

JA: There are a number of Inquire Within or miscellanies like the Gloucester Manuscript in other ancient book collections. So why did they suddenly begin to appear at this time in the languages that the ordinary people actually spoke and understood, rather than the Latin of previous times. One reason was the Europe had just been through one of the greatest cataclysms in its history – the first wave of the Black Death which killed up half the population, between 25 and 50 million people were dead. Here’s Mark Clarke again:

Mark: This is my idea, is that a lot of these medieval recipe books from the middle of the 14th century onwards, they start being written in the vernacular. So instead of writing them in Latin people start writing them in their own language. And this is happening in Italy, it’s happening in Germany, and it’s happening in England. And I think that this is a reaction to the Black Death. I think that what’s happened is if you’re going to be a specialist craftsman, you need a critical mass of consumers to support that. And I think what happens is, in a stressed community, such as after the Black Death, what you have is a more of a D-I-Y mentality. So, you’ll have farmers who are also silversmiths, you’ll have farmers who are also blacksmiths. You’ll have monks who are no longer buying stuff in, they’re making, making it themselves. They’re households who are going, you know, the ink seller hasn’t been around for a while. Let’s just make ink. Or we need to make these clothes last even longer than we used to. There are recipes where, what they call refreshing cloth, you know, which is essentially dying it again, essentially, you’ve washed it and washed it and washed it, and it’s looking a bit drab. You’re not going to get new stuff. You can’t buy the materials. Nobody’s making it anyway locally. I will freshen it up by giving it a, a, a home dying much as much as you can now. And I think that there is this couple of things happening at once in, in the wake of the Black Death one is this DIY mentality that springs up a bit. Secondly, there’s this sort of panic among the literate about let’s just preserve this information for when civilization collapses.

JA: There was an end of times sense, that they had to get everything down in case the information was lost, and at the same time we see the beginnings of a new age coming, says Mark: the surviving elite began to take an interest in craftsmanship, and journeymen are travelling from place to place at the end of their apprenticeships looking to extend their craft skills.

Mark: You know, you go walking around and you try and find odd jobs from other masters in different towns. And they go, oh, you do it like that. And so they write that down. So stuff they haven’t personally learned that they haven’t internalized yet, they will write down notes of that. So that’s another source of recipes getting written down. Now you also get, again, in the 14th, 15th century, you get a top down interest in craft from the elite. And it was interesting. So you get things like the king’s chef will write down recipes of the best banquet and the best recipes. And this is happening in France and in England at the same time. And their best practice. And that, and these get copied for maybe a hundred years. So you can get a fresh copy of it that reflects a banquet that took place a hundred years ago because It’s amazing stuff. But there’s this sort of concern to preserve and memorialize best practice.

JA: And this is what Mark thinks was happening with the Gloucester Manuscript, it seems to have been written by one hand, copying out recipes and useful information from a whole host of sources to preserve it and to use it where necessary. Inevitably because the unknown monk was making a copy of a copy, mistakes have crept in, especially because he was a monk and not a skilled craftsperson in the trades and techniques he is transcribing. But we are still left with the sound of a monk hurrying to get down all the knowledge he could find and most of all with a lost world of colour created by the craftsmen called stainers, who have vanished completely leaving barely a ghost of the richly tinted and hued world they created. All we have now are the written records like the little Gloucester manuscript and the respect and understanding of people like Jorge Kelman who have worked to recreate their recipes:

Jorge: Well, anyone who explores traditional methods of things tends to find out that there’s a lot more preparation and creation of materials than there is today. So a painter would typically know how to grind their pigments and source them to where to buy them from and then prepare them, check them for quality, and then turn them into paint.

So yeah, I, I have a respect for anyone who has to make and prepare their own ingredients for things. And, that goes to my dyer friends and painter friends, carpenters and people that have to have to go. They can’t just buy what they need. And that goes to modern crafts people too. So, if I watch videos of, of block printers in India and Jaipur or something, I watch them with great fascination because they are the front end of those end products is the making of the woodblock, the cutting of them, the mixing of the dyed stuffs. That someone that’s has been at the physically at the end of those processes, it’s not simply come from a shop or factory, and that still happens today. I suppose any of those things that you have a primary interaction with your materials, I think is, is, is well worthy of respect. So I have a great appreciation of that, certainly.

Thank you to Mark Clarke, Jorge Kelman, and Rebecca Philipps who takes care of the Gloucester Manuscript in the wonderful library at the Cathedral. Without their knowledge, thoughtful research and scholarship this episode would not have been possible. Thank you too to Joanna Teague who took me to see the Gloucester Book, she too has been successful in making up a number of the staining recipes, as well as the Gingerbread!

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and edited and produced by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast independent, and free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you extra content every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted by Bill Taylor and me, where we cover a whole range of different textile news and topics. You can find out more about this episode, and see pictures of the stained cloths we have been talking about at www.hapticandhue.com/listen-series-6

We will be back next month with a new episode. Join us next time on the first Thursday of the month and until then – thank you for listening and enjoy whatever making you are doing.