Episode #48

Jo Andrews

This episode of Haptic and Hue looks at tapestry weaving and the process of collaboration that goes on between an artist and a weaver to produce a new work. It asks if tapestry weavers are forever destined to be seen as anonymous helping hands, or if their skill, craft and artistry are now, finally, beginning to be recognised as an art in its own right. We talk to a gifted tapestry weaver about what it is like to work on a piece for several months and how much of herself she pours into each new weaving. You can also hear an artist and a weaver talk about how they collaborate to turn a piece of art expressed on paper into one expressed in wool.

Notes:

Katrina London is Curator at Kykuit, which is on the Hudson River not far from New York City. The House is open in the summer for public tours. You can find out more information at https://hudsonvalley.org/historic-sites/kykuit-the-rockefeller-estate/

Dovecot Studios is in Edinburgh and is free to visit. You can watch the tapestry weavers at work from the balcony. https://dovecotstudios.com/ You can follow Dovecot on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/dovecotstudios/ . Dovecot also holds excellent textile exhibitions and shows of different kinds and it has a good café. If you are in Edinburgh it’s a great place to meet as there is always something interesting to see.

Weaver, Ben Hymers is on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/ben_hymers/

If you want to discover more about Sekai Machache and her work head over to https://www.sekaimachache.com/. She is on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/sekaimachache/ and you can find out more about her art from this conversation on You tube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4PX93QSB6vE

Katrina London – Curator Kykuit

Picasso Gallery at Kykuit – Courtesy of the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation

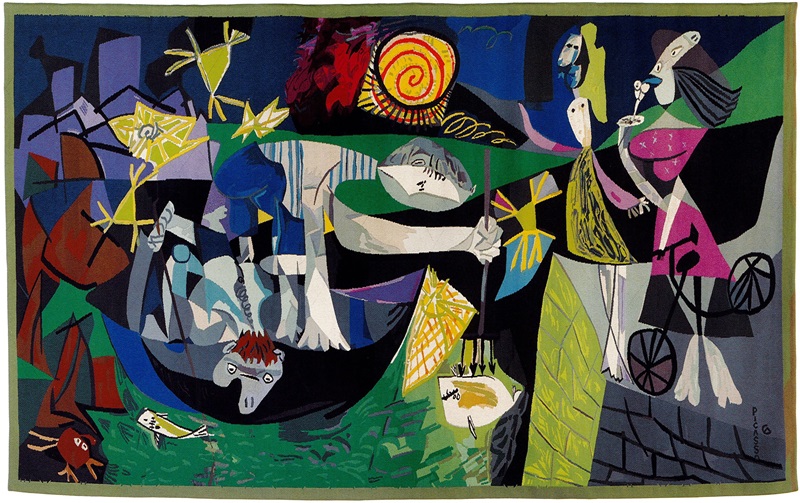

Night Fishing at Antibes – Courtesy of the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation

Three Musicians – Courtesy of the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation

Jacqueline de la Baume Durrbach – Municipal Archives Marseille

Durrbach family – Muncipal Archives Marseille

Dovecot Studios Edinburgh

Naomi Robertson, Head of Studio, Dovecot Weavers

Celia Joicey, Director of Dovecot Studios

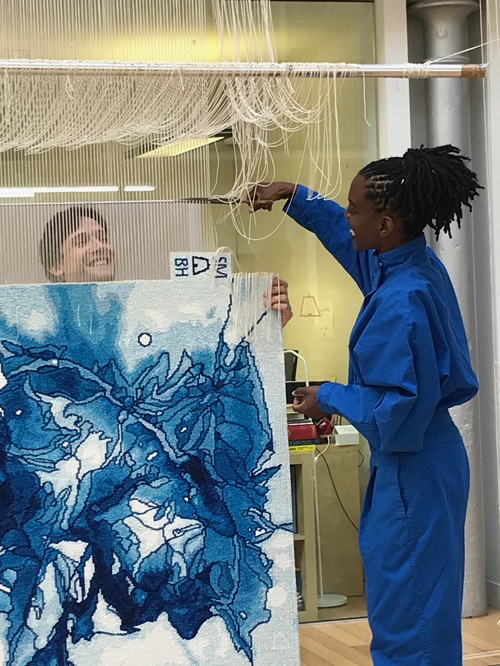

Sekai Machache cuts off Lively Blue as weaver Ben Hymers holds it up

Lively Blue designed by artist Sekai Machache, woven by Ben Hymers

Black Cat – Part of a Tapestry woven by Dovecot Weavers of a Painting by Elizabeth Blackadder

Flower, From a Weaving by Dovecot Studios, designed by Elizabeth Blackadder

Script

Invisible Hands: Tapestry Weavers and Artists

JA: Welcome to Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews. I’m a handweaver, interested in what cloth tells us about ourselves and our societies. Often the stories and information that textiles give us are ignored and we lose a whole dimension of human experience. And far too often the hands that create the textiles we treasure remain unknown and anonymous. That’s very much the case in this episode where we look at the relationship between artists and tapestry weavers. It is the weavers’ hands and skill that transform an artist’s ideas into tapestry and often transform it into something special, textured and tactile with a depth that is unique and yet it is the famous artist whose name is attached to the piece and the weaver who is forgotten. I want to understand why this had happened and if it is changing.

Some time ago when I lived another life with a job that required me to get on planes and think about the problems of the world, I was invited to a conference at a centre about thirty miles outside New York City. I remember nothing about the conference, but at some stage I was asked if I would like to see the grand house on the hill and its art.

It was an incredible collection of painting and sculpture, the kind that lifts your heart even when you are suffering from appalling jet lag. And there was something truly special there – that I will never forget. A long gallery in the house was filled substantially with extraordinary woven tapestries rendering the work of Picasso into something new and exciting, somehow transformed from flat canvases into images with much greater texture and density, to my eye they were true masterpieces:

Katrina London: Visitors do have that impression that you, that you had as well. Those who are familiar with Picasso immediately recognized that it’s Picasso’s work, but they see that this is something different and they are not usually aware that he was involved in tapestries. And so they’re usually amazed by them. They’re very striking, brilliant colours. And, you know, it’s, it’s great to see their visitor’s eyes widen in amazement as they turn the corner into the gallery. And most of the visitors, even if they’re not that familiar with tapestry techniques, they always marvel at the high-quality Mm-Hmm. <Affirmative> of the weaving. The visitors who are the most blown away by the tapestries are often very reluctant to leave. One Frenchman who visited even said he wanted to spend the night there, <laugh> <laugh>

JA: That’s Katrina London who is the Curator Collections at Kykuit, which is the mansion the Rockefeller family built themselves high above the Hudson River. It was members of this family who helped to found the Museum of Modern Art and New York’s Cloisters Museum which displays Medieval Art. With money and taste the Rockefellers also filled their own home with fine pieces:

Katrina: Kykuit is a four storey Beaux Arts Villa that was built between 1908 and 1913 as a country home for Standard Oil founder John D Rockefeller Senior and his wife Laura Spelman. It’s located in Tarrytown, New York, which is about 25 miles north of Manhattan. And it’s perched high up above the Hudson River with astounding views. The house was, was home to four generations of the Rockefeller family. And the first three generations in particular left a mark on its collections, which include highlights such as English and American furnishings, antique Chinese and European ceramics, significant portraits, 18th century French prints and exquisite, woven textiles.

JA: In particular Nelson Rockefeller – Governor of New York and also Vice President of the US under Gerald Ford – loved the work of Pablo Picasso and he commissioned or acquired 19 woven tapestries of Picasso’s work as a sort of retrospective of his career.

Katrina: So the tapestries depict some of Picasso’s most notable paintings from over 50 years of his career, from his early cubist works of the first quarter of the 20th century, such as Girl with Mandolin and Harlequin to a more ominous scene, Night Fishing at Antibes, which was painted on the eve of World War 2 and then some more jubilant depictions in the south of France after the war, like Nude on the Beach with Shovel. Three of the tapestries were actually based on paintings from Nelson Rockefeller’s own collection. He owned Interior with Girl Drawing, Pitcher and Bowl of Fruit and Girl with Mandolin. And then four of the tapestries were based on paintings that the Museum of Modern Art had in their collection. Harlequin, Three musicians, the Studio, and Night Fishing at Antibes. The tapestries are all much larger than the original paintings. Some are as large as nine by 12 feet, so they’re really like mural size.

JA: Nelson Rockefeller was a man who could afford the actual paintings of Picasso so why did he commission so many tapestries?

Katrina: We don’t know the exact stated reason that Nelson, you know commissioned such a large amount of these tapestries. But it has been noted that it allowed him to really display almost like a small retrospective of Picasso’s career transformed into another medium, which I think was exciting for him. They were also less valuable and fragile and much more portable than paintings. So, they would lend themselves to changing installations and locations, which appealed to Nelson because he had a real passion for art installation. And he loved to move works in his collection around frequently trying out new placements. Also, another possible source of inspiration, or at least appreciation of tapestries as a medium. He grew up around some of the best tapestries in the world. His father John D Rockefeller Jr, who was a philanthropist, displayed the incomparable unicorn tapestries in their 54th Street town house before he donated them to the Cloisters in 1937. So Nelson’s father was a great lover of medieval art. He was one of the founders of the Cloisters. And his mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, was a major patron of modern art. And so it’s kind of interesting that the Picasso tapestries sort of marry these two traditions in a sense.

JA: There is little doubt that Nelson Rockefeller loved his Picasso tapestries. He took many of them to the Governor’s Mansion in Albany New York, Katrina says he really wanted to show them off and share them with others, and he was happy to lend them freely to museums and galleries:

Katrina: One last anecdote about Nelson’s reception of the tapestries is that he wrote a touching thank you letter to Picasso in 1970. He writes, quote, it would be difficult to express fully the joy and excitement of anticipation that I continue to have in living surrounded by these masterpieces. End quote.

JA: If you ever have the opportunity to see these tapestries – please do it – they are simply incredible. But this story raises a whole host of questions for me about hidden hands. Nelson Rockefeller wrote his letter of thanks to Pablo Picasso, when visitors see these works of art at Kykuit they immediately recognise them as Picassos. But it was not Picasso who made these tapestries, these were not worked by his hands and it was not him who laboured over a twenty-year period to finish this commission. Very few of us will ever have heard the name of the weaver who did.

Katrina: So she is Jacqueline de La Baume Dürrbach. She was born in France in 1920, and she studied at the Académie Julian in Paris, where she met her husband, René Dürrbach. He was a sculptor, painter and designer of tapestries and stained glass. Jacqueline studied sculpture for three years, and then she trained in low warp tapestry weaving with the Aubusson Master, Beaudonnet. And then she set up a studio in Cavaliere France in the Var region. And there Jacqueline began to weave her own designs, also designs by René, and then began making weavings after cubist masters. And then each Picasso tapestry that she made took her between three and six months, depending on the complexity and the size. And Picasso was living nearby in the south of France, and he collaborated with the weaver on colour choices, and he always approved the cartoons, and then the final weaving. He gave Jacqueline permission to weave three identical versions of each composition. So, the first was meant for Nelson Rockefeller’s collection, the second was for Picasso himself, and the third would remain at Dürrbach’s manufactury.

JA: So here is someone who spent twenty years of her life in close collaboration with Picasso producing something that extends his art and transforms it into another medium – but she remains unseen – well almost.

Katrina: The designs of the tapestries are certainly by Picasso. His name is woven on the front of them in block letters, very visible. But the weaver, Jacqueline de La Baume Dürrbach is also attributed on the face of the tapestries with her trademark symbol, which is an A within a C. So technically they’re co-signed, but of course everybody always sees Picasso’s, <laugh> name first and doesn’t necessarily know what the A in the C is. But during tours and in our labels and text panels in the galleries, the Weaver really gets her credit for, for the, as being the maker and the one who translated them into the tapestry medium. And so our museum educators definitely talk about this during the tour. But I think you’re right that a lot of people just see them as Picasso and they’re confused about the whole commission and, and the collaboration and how it all came about.

JA: But Katrina says in some sense Jacqueline’s hands are incredibly visible, as it is her work you are looking at when you see the tapestries:

Katrina: So we try when we’re sharing with visitors to talk about how important her role is and, and you know, I think for a long time her artistic career was sort of in the shadows and many people just dismissed the tapestries as copies and not so important.

JA: But importantly Katrina thinks those shadows may be clearing a little:

Katrina: Yeah, I do think it’s changing. There’s been a good deal of new or recent scholarship on modern tapestries and the vogue for them at mid-century and all the different players in the, in that realm and the makers. And I’ve, I’ve heard murmurings of, you know maybe exhibitions will be organized that involve Jacqueline De La Baume Dürrbach or feature her. So, I think things are finally starting to change.

JA: The close relationship between a tapestry weaver and an artist is not unique to Picasso. Marc Chagall, the Russian French artist, had more than 40 of his works transformed into luminous works of tapestry by the Belgian weaver, Yvette Cauquil Prince. They had a close personal relationship, so much so that Chagall’s wife, Vava, became intensely jealous and banned Yvette from Chagall’s company for ten years. Chagall called Yvette the Toscanini of Tapestry and she said of herself: “I am like a conductor, and Chagall is the music. I must understand the work of Chagall so profoundly that I myself do not exist.”

But how do modern tapestry weavers see themselves: as craftspeople like Yvette aiming to disappear, or as artists in their own right? Naomi Robertson is the head of Studio at Dovecot Weavers in Edinburgh. She manages a rare modern tapestry studio of six weavers who work to a mix of commissions and speculative pieces which they hope they will find a buyer for.

Naomi Robertson: I see myself as a, a weaver, a crafts person and an artist. I think as a weaver, and because we’re a studio weaver and because we’re weaving alongside each other, the technical needs to be constant. So everybody needs to be able to weave in the same manner. So that’s very important. But then I think the interpretation of somebody’s work that we bring to it is very much and artistic. We are, we are looking at colour, we’re looking at mark making and in each different project we have to find the weaving solutions for that person’s work. So, we are not copying paint marks, but we’re finding solutions in our medium for it. So, I think of it as a really creative process. So, I think of myself as an artist and a craftsperson.

JA Naomi herself is a gifted weaver. I love her rendering of a painting by Joan Eardley called July Fields. Eardley was a celebrated Scottish painter of the mid twentieth century, and Naomi has given this work both a depth and texture that transforms a beautiful painting into a different but equal art form.

Naomi: So by translating it into wool and yarn, it has a different quality. In something like a painting, the light reflects on that surface. If you weave it, the, the wool absorbs the light and almost resonates. It’s, you get a much richer feeling. And I think we all probably also connect with textiles in a way. So I think there is a kind of living relationship with the textile and a tapestry, but there’s definitely a depth of colour. And I think a lot of that, again, is to do with the way that we mix colours. If you wove with a flat, perfectly dyed matched colour, the tapestry would look very flat. And one of the things that we pride ourselves on is the mixing of yarns on the bobbin, which really brings a colour to life. And often it can have something quite unpredictable in that mixture that just makes a colour ping.

JA: As a studio Dovecot has a number of weavers and each of them might work on the same tapestry. This is very different from being a lone weaver working on your own. You work in a much more collaborative way with you colleagues.

Naomi: At the start of a project, we do a lot of sampling. We work out a palette, we work out the mark making, so we are all coming at it from the same place. And a weaver wouldn’t necessarily sit on the same spot in a tapestry. We might move across from one bit to another. You might pick up somebody else’s bobbins. And we do a lot of talking while we’re weaving, I might say, oh, I like that colour. What’s in it can have, it’s all talking to each other while we are talking, so so is the tapestry. So it’s, it is a constant kind of conversation that’s going on about what’s happening.

JA: To Naomi this is a conversation amongst the weavers themselves and then between the weavers and the tapestry which speaks to them.

Naomi: I think so. And yeah, it’s it’s all embroiled up in one. Your whole life is embroiled in the tapestry. As you’re weaving it, you know, you weave in your worries, you weave in your happiness. It all all gets woven in because you know you’re living it at the same time.

JA: And when she looks at a tapestry she has helped to weave Naomi remembers what was happening in her life at that time:

Naomi: Absolutely. It’s quite scary how I remember things because I remember what was happening in my life at the time that I was weaving it. I mean, you live and breathe it for so many months and you have good days and bad days and it’s, it’s all very much, excuse the pun, but interwoven. Yeah.

JA: Dovecot Studios over the years have worked with many famous living artists and translated their work into tapestries. These include David Hockney, Eduardo Paolozzi, Elizabeth Blackadder, Yinka Shonibare, and Kaffe Fassett to mention a few. The pop artist Archie Brennan, of course started as a weaver at Dovecot. And at the beginning of each new project there is an interesting dialogue between painter and weaver:

Naomi: I suppose at first you’re in awe, but you very much, I feel quickly become an equal once you get down to that artistic conversation and it’s just two people or whatever round the table. You are equals and you’re just discussing how to get to the right place with that tapestry. And it is just such a wonderful thing when you get down and, they respect us because they have to trust us with their work. So trust building’s probably one of the first hurdles to get over once you’ve got that relationship established, but trust because they are putting their work in your hands, they’re putting their name to that work, so they need that reassurance that you’re going to represent their work in the best way possible. And then you get down to things like colour and mark making and you know, in an artist’s work, there are marks, they didn’t make that happen. So it might be a paint splash, it might be a pool of water, it might just be a scrape. And they’re often not aware of them, but they, they make their work, you know, they are part of their work. But we have to decide which of those goes in or doesn’t. So, things that are made by, you know, the flick of a hand or a spot of paint and are incidental, we have to make the decision to put them in, do you make more of that mark? Do you make less of it if you took them all away? It wouldn’t be the artist’s work either. So, when you make an artist peer into their own work in the way that we do, they do see it from a different perspective. And because we start at the bottom and work up again, an artist, we’d never start at the bottom of a canvas and work up. So again, they are looking at a strip of their work at a time so that, you know, it’s, it’s quite interesting.

JA: I love the idea that the tapestry weavers can help artists see their work through new eyes by really looking at it. All the pieces that Dovecot finishes are marked with the artist’s name and also, importantly, Dovecot’s own symbol of, yes, a Dovecot. For a long time, I thought this was deeply unfair, and that the individual weavers should get equal billing, but Celia Joicey who is the Director of Dovecot Studios has a different view:

Celia: Dovecot Studios is a studio tapestry workshop. So, we see the team as a, as a team, and often a tapestry can be created as a collective endeavour. And I think that’s where we see our place in modern contemporary tapestry. And it’s exciting to work on collective projects. And I think as a society we’re not always as good as we need to be about talking about an achievement that is made by a number of people. It’s not just one person who makes something successful. So, we would like for tapestry to be seen as the embodiment of how as a team you can create something that’s beautiful. There’s a vision that a team can have as a team.

JA: Celia says that all of Dovecot’s pieces do contain some record of who worked on it.

Celia: On every work that the studios create, the initials of the team members who’ve worked on it are recorded along with the Dovecot symbol and the initials of any artist or designer that came up with the original imagery that’s been interpreted. We recently contributed to a study day at the Burrell, which is the famous tapestry collection created in the early, well late 19th, early 20th century by William Burrell that’s in Glasgow, that’s reopened. And at the Burrell study day, the historians of the Renaissance, even earlier medieval tapestries, were talking about their challenge in not knowing that detail, not knowing who had actually worked on different tapestries. They could tell the studio, but not the individuals and how many individuals and, and what that story and that journey was. So, it is important to record the individuals, but equally going back to the point about collective endeavour, it isn’t always the will of the media, the sometimes the museums and the galleries, to want to represent the collective act as opposed to the hero individual. And that’s interesting.

JA: She’s right it is interesting and in contemporary society with its emphasis on individual celebrity and freedom– the hero artist is routinely lionised over the work of a team. It seems too that textiles crafts are almost by their nature collective or team work, think of linen production or wartime quilt-making in Canada, and because many of them have been traditionally the work of women does it mean that their names are more likely to have been subsumed within the team? But there is also the hard economics of life for a studio like Dovecot. A buyer is far more likely to pay the price it costs to create a new tapestry if it is by a famous artist – rather than a studio collective.

Celia: So it would be nice to think that the economics of what we do are made more viable through clever choices in terms of who we work with. But alongside that is the opportunity to cross-fertilize the funding that we have to work with an artist that might be emerging. So in the last couple of years, we’ve provided opportunities for our weaving team themselves to come up with their own designs. It’s not always the case that they would weave their own designs. And then we’ve come up with opportunities to work with emerging artists and we’ve supported that.

JA: And on the day I was at Dovecot they were cutting off a completed tapestry that was a result of working with just such an emerging artist. Sekai Machache is a young Zimbabwean Scottish artist. Cutting off days are times of celebrations and moments of anticipation. Finally, a work that has been planned and then executed over long months can be seen. Often the artist is there to see what the weaver has made of their art, as Sekai was to see the work called Lively Blue inspired by her abstract ink drawings taken off the loom:

Sekai: It’s really exciting. It’s kinda surreal actually, because I just remember making this ink drawing alongside all the other ones that I was making years and years ago. It was 2019, 2020 sort of time. And to see it turned into something completely different. But, you know, with so much of what the, the original has, but it’s, it’s, it’s very, I don’t know of another word apart from just exciting. And it is a bit surreal. It feels like they’ve really, really captured it.

JA: But she says there is also something extra seeing her work in a new medium:

Sekai: Yeah, definitely. There’s new textures, there’s new dimensions of colour. There are things that I couldn’t, wouldn’t have been able to do with just the ink on paper. There’s just so much density to it and so much intricacy and detail.

JA: The piece is a kaleidoscope of different bright blues against neutral colours and the original ink drawing is a work that stems directly out of Sekai Machache’s interest in indigo:

Sekai:. And I’d been sort of investigating the history of indigo in lots of different cultural contexts, but particularly related to the transatlantic slave trade and the ways in which Indigo was traded alongside many other commodities such as sugar and tobacco and so on. I felt like one of the things that is missing from our conversations a lot of the time around the slave trade is the reason for it. And it’s about extraction, really. It’s about extracting commodities and selling them and trading them around the world and utilizing those commodities to create wealth. And in doing so there was this exploitation of labour of African people. So for me, it was about looking at the commodity to understand the trade, to understand the history. So I went specifically with indigo because I was already working with the colour blue.

JA: There was just one weaver of Lively Blue – Ben Hymers. He suggested making this work to Dovecot:

Ben: I’d seen Sekai’s work at Still’s Gallery and remember saying out loud, like, to anyone passing by that, that would make a really nice tapestry, which is obviously probably my want to go around and look at stuff like that. It’s almost like a ready-made tapestry design, if you like. It’s got such a nice connection to cloth generally. And also just, just the weight of the lines and the shapes that are made in Sekai’s drawings are sort of naturally made shapes for tapestry. Just something about it, look at it and thought that would, that would be a pleasure to weave. And it has been, it’s been a joy to weave.

JA: Ben says his work is about effective transformation.

Ben: I’d describe myself as a crafts person rather than the artist. It’s like translating something into another language. You can’t just do it perfectly word by word because it wouldn’t actually make sense. You have to get the essence of the idea, of the whole sentence or paragraph or metaphor across. And that’s kind of what you’re doing in, in the tapestry situation, is turning anything to some extent into the language of tapestry, hopefully.

JA: But interestingly it is the artist here, Sekai Machache who sees Ben as her co-creator:

Sekai: This is a collaboration and I think that Ben is the artist of this tapestry. I am the the designer of the image. And I’m very, a very like important aspect of my practice as an artist is collaboration. I actually collaborate with people all the time. Yeah, there’s a whole group of people that are involved in making my work all the time with me. So, I’ve never really felt precious about anything in the sense of I know what I bring and I, I invite people to, to support and work with me all the time. So, in this instance, it’s kind of an extension of something I’m already doing in my, in my own practice.

JA: And as an artist with a different, more collaborative method of working, and working in lots of different media, including film, she rejects the notion of the hero individual, the famous single name that stands above all.

Sekai: I don’t think that’s a fair way to work. Like I feel that crediting people is really, really important. I’ve been working to make sure that Ben’s voice is really, really heard in the process of making this, we’ve been making a film which is going hopefully be part of the exhibition sort of process and everything. And it’s going on my website and it’s, yeah, interviews with Ben, talking about the process of making these interviews with me, talking about the process of making the ink drawings and the overall ink drawing project that I’ve been working on for a few years now. So it’s important to me that, that Ben gets to speak about this because this is hours and hours of work. I think exploitation of labour is something that I’m talking about in my work already, and I wouldn’t want to, you know, forget the people who made the work.

JA: Lively Blue – the beautiful piece designed by Sekai Machache and woven by Ben Hymers – is for sale at Dovecot if you have deep pockets. Thank you to both Sekai and Ben for letting me pester them with questions on a big day. Thank too to everyone else at Dovecot Studios who weaves in that beautiful place and helps to keep it going. Pay them a visit if you are in Edinburgh, and if you can’t get there, there are always Jaqueline de la Baume Dürrach’s fantastic translations of Picasso’s work at Kykuit on the Hudson River in New York – thank you to Katrina London for sharing her knowledge and expertise of them.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and produced by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast independent, and free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you extra content every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted by Bill Taylor and me, where we cover a whole range of different textile subjects. You can find out more about this episode, and see pictures of the tapestries we have talked about at www.hapticandhue.com/listen – series-6.

We will be back next month with a mystery book that lies in an ancient cathedral. It contains everything you might need for a good life at the end of the 1300s, including some wonderful recipes for creating brightly coloured fabrics and banners. Join us next time on the first Thursday of the month and until then – thank you for listening and enjoy whatever making you are doing.