The Garment That Sweeps Through History:

The cloak has kept us good company throughout the centuries, it has marched with armies across plains and deserts, it has been sanctified and worn by saints, and was just as beloved by sinners like highwaymen. It became the emblem of witches on broomsticks and superheroes flying through the sky. It was worn by hobbits to make them invisible and it is still revered as the ultimate in stylish outerwear by Venetians.

This episode of Haptic & Hue looks at the cloak, cape, cope, mantle, and all its other many forms through history and tries to answer the question of why it has proved such a joyful, useful and versatile garment.

Notes:

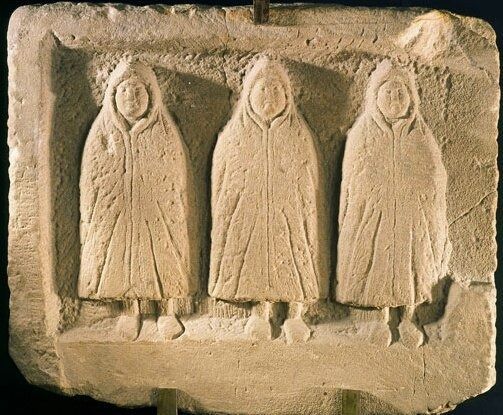

Hadrian’s Wall is a World Heritage Site in Northumberland and Cumbria. You can find out more about it at www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/hadrians-wall/ . At Housesteads Fort you can see the wonderful stone relief of three figures wearing the Birrus Britannicus.

Sue Day works at Chedworth Villa, in Gloucestershire, where you can see the mosaic of Winter wearing his cloak.

Amica Sunström is at the National Museum of Sweden in Stockholm and she is on Instagram as @historical_textiles

Maria Stella Busana is the author of several articles and books on Roman excavation and clothing.

If you would like to see the Zara family’s cloaks or even order your own – and frankly who wouldn’t – you can find their beautiful tabarros at www.tabarro.it

Sue Day holding a reproduction of ‘Winter’

Romano British Winter Cherub at Chedworth Villa, wearing a cloak

Stone relief from Housestead Roman Fort on Hadrian’s Wall showing three Romano British Spirits wearing the Birrus Britannicus

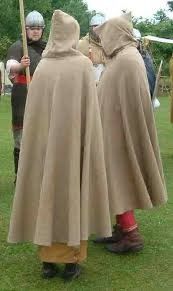

Reconstruction of a Birrus Britannicus. Photo courtesy of Stephen Kenwright

Amica Sundstrom

Gerum Cloak – Swedish National Museum

Gerum Cloak – Laid out, showing the stab holes. Picture courtesy of the Swedish National Museum

Sagum cloak, worn by a re-enactor

Maria Stella Busana

The Madonna and Child by Bernardo Daddi, 1338. She is wearing her blue cloak in the style of a Roman woman’s Palla

The Three Kings in their Magnificent Cloaks. Mosaic from 565AD, Ravenna

St. Martin of Tours gives his cloak to a beggar, 1474. Fresco, St. Mary of the Rock, Istria, Croatia

The Zara family in their cloaks. From left to right – Vittorio, his father Enrico, and his father Sandro

Cloaks made by the Zaras

The Italian army in their cloaks, 20th Century – Zara Collection

The 15-18 cloak

Katya Simeon who makes the modern Tabarro

Superman in his Cloak

Modern cloak fanciers in Padua, Italy

Princess of Wales wearing a red cloak, 2023

Script

The Garment That Sweeps Through History: The Everlasting Cloak

Jo: Its February and we are on Hadrian’s Wall in the north of England. The Wall was built in the second century AD at the command of the Emperor Hadrian to defend the north west frontier of the Roman Empire: its barely light, there is frost on the ground and a bitter wind is blowing straight out of the north east. As a soldier in the Roman army you are standing on the wall – on duty – probably wondering how on earth you got yourself into this mess. But, you can see that the local tribes are wearing something very practical that keeps them warm and dry – and it’s called the Birrus Britannicus:

Sue Day: The Birrus is an all-in-one cloak from ankles to head, and it’s got no seam and apart from one. And then it’s all woven on one loom in one piece, and then just sewn up the front. And the only way you can get into it is by climbing into it and hopefully getting your head towards the hole. And the hood is also attached. And so, when it’s on, it’s actually down to the ground and up above your head. And, you can’t do anything because your arms are inside.

Jo: That’s Sue Day who recreates ancient textiles, and I’m Jo Andrews, the host of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m a handweaver, interested in what cloth tells us about ourselves and our societies. Often the stories and information that textiles give us are ignored and we lose a whole dimension of human experience. This episode is about cloaks and capes, a piece of clothing that has as good a claim as any to being a universal garment. It crosses cultures and centuries. It has accompanied humanity down the long march of time and has been repurposed and reshaped by almost everyone from saints to sinners, from highwaymen to hobbits. You could spend a lifetime researching this one garment – but here is an episode of Haptic and Hue that looks at just some aspects of the all-purpose cloak.

Sue works at the Chedworth Roman Villa in Gloucestershire, and she has made herself a Birrus Britannicus.

Sue: It is very restricting, but it’s a waterproof coat or cloak, it would’ve been warned by virtually everybody, including all the plebs out in the fields. You may know of them as plebs, that’s the shortened word means the common people out in the field, the workers. But it would also have been worn by the, the higher officials as well. And the soldiers would’ve been wearing them as well. Now, it was well known that if the Roman army was on march, they would send out scouts and those scouts would go to any occupied area. So, for instance, our villa is only three miles away from the Foss Way, and they would actually go to the villa and several others that are around us and commandeer all of the woven material. And that includes all the cloaks and everything else. I always tell people that if you heard the Army were on the march, you hid everything <laugh>.

Jo: The important thing about the Birrus Britannicus was that it was warm – but magically it was also waterproof:

Sue: It was made from sheep’s fleece, sheep’s wool, and it was just washed. So, to get rid of all the dirt and all the mucky bits of sheep, it would then have been spun and woven in the grease. So, you’ve still got the lanolin. So, once it was made and you’re wearing it, it’s all covered in lanolin. So, when the rain hits it, that runs off. Now we know it would’ve been spun as a worsted spin. So that’s spun along the fibres because that’s the best one to help the rain also runoff as well. It’s almost like today’s wax jacket. You could think of it in the same way. You know, the Barber wax jackets, you put those on, they’re covered with the covering of oil to help the rain and their waterproof as well. And windproof, which the Birrus would’ve been as well, it was a tightly woven cloak.

Jo They were restricting to wear because they had no armholes and no open seams, if you wanted to use your arms you had to hitch the cloak up until your freed an arm, but they became highly coveted in Rome, where they were prepared to pay a huge amount for them:

Sue: But we do know that during the second century one of the emperors, Diocletian, actually wrote the Edict of Diocletian. And the second item on his list of exported items was a Birrus Britannicus, and that was worth, in today’s money, 250 kilograms of pork.

Jo: That’s a great deal of pig in anyone’s terms – about 550 pounds in weight. Diocletian was setting what he considered to be fair prices to be paid for items. Of course, being a textile, there is no surviving Birrus that we know of, but at Chedworth Villa there is a Roman mosaic of the seasons, and depicting Winter is a little cherub like figure wearing a representation of a birrus. And not far away in Cirencester Museum is a tombstone with three men on it, who could be soldiers. They appear to be wearing the British cloak. All you can see are their faces with their toes sticking out at the bottom. But there is a cloak that is more than two thousand years old and it’s in pretty good shape:

Amica Sundstrom: I will say it’s a perfect condition. It’s a fabric who is 2000 years old, and when it’s preserved in a bog it’s the best for wool. So, that one is, is a perfect shape. They have some holes in it, like they were digging. They make some holes and, and also, they have some holes from how it was used. And you can still like lift it without breaking it. It’s, it’s fantastic.

Jo: This is the Gerum Cloak which is around 2,300 years old, and that’s Amica Sundström, a weaver and textile archaeologist at Sweden’s National Historical Museum. This cloak is remarkable in so many ways. It was found by chance in the 1920s in Western Sweden.

Amica: And these two men, they were digging in the bog. They, they needed to light the fire, the the material. And they, they found this, it was a package, the cloak was folded in a packet and was three stones on top of it. So they thought it’ll be like something very expensive inside, but we know it was the cloak was the big present here. So maybe they was a little disappointed, but they still understand that this was an old thing. So they, they contact the museum in the area, and they come out and look at it and say, this is very special. So they send it up to, to Stockholm.

Jo: It’s Sweden’s oldest complete garment and the reason it survived and none of the British cloaks survived is because it was in a bog:

Amica: And for wool textiles in, in all part of the world, bogs is the best things ever. So from Denmark, they have fantastic bog finds. You have it in Ireland and probably we have much more Sweden, but we have so much trees here, so we haven’t digs so much in the, the bogs, like they have done in Denmark. (Laugh.)

Jo: This isn’t the British onesie – it’s a much more elegant and fashionable version of the cloak – especially for its day. It’s the earliest surviving representation of a hounds’ tooth twill that we have anywhere in the world. It was made from natural coloured white and dark wool, warped in four strands of white and four strands of dark wool and then woven in the same way. The cloak is all deep brown now because it has been stained by the bog, but originally it would have been a striking brown and white. This is a pattern that has come down to us and is still used by designers. In black and white it practically became the house pattern for Christian Dior, and Coco Chanel’s 1960s tweed suits made great use of it. And indeed, Amika thinks that when this cloak was made it too would have been the height of fashion:

Amica: So fabric is like something very new and very unique. And this, this one have also been amazing. You have to see the colour pattern is white and brown. You see it from long distance. It’s very powerful. So, it obvious there are only people who have connection or some kind of power who, who development is textile and, and been using it. And cloaks are a big piece of, of cloth. So, it’s of course a lot of effort put into it: And, and you can show it off in a big way. you see it and look looking and you see them, the person have it and say, wow, that the purpose is also wow. But then you have, the purpose of hold you warm. Sweden and Denmark is not a very warm country, so you also need it to stay alive.

Jo: So, it has these two purposes. It keeps you warm, but it’s also, it’s fantastic for showing off.

Amica: Yeah, I think that part is very important here, because also not everybody can have this, , so it’s very special, the knowledge about the weaving, and also to have the sheep and to make threads of is quite new

Jo: And the Gerum cloak is a big piece of material: two and half meters long and two meters wide, that’s about 8 foot by 6 foot 6 ins. It would have looked spectacular AND it would have been extremely useful in keeping out those cold Scandinavian winds. And here lies part of the cloak’s charm and the reason for its universal appeal, it’s both showy and practical. Amica and her colleagues know that this cloak was woven on a Roman style two beam loom, and they have been able to show that it was made by two weavers working side by side. The method they used was that both had a shuttle and entered it at each side of the warp meeting in the middle and crossing threads there: or as Amica notes not quite in the middle:

Amica: So, it’s actually very clear that you see that. And so on one side you see this crossing very well, and the fun part is also, they’re not exactly in the middle. It’s little more on one side. So, I imagine that they, that are two people, one have like longer arms or are faster on the other one, so they don’t come exactly the middle. And I love these times like this because you get very close to the people who have made it and like, yeah, it’s become your friends. Like you think about how they have sit sitting there and weaving this and, and like, I’m little faster than you and you the crossing coming on your side <laugh>

Jo: And that’s what the careful study of textiles can do for you, take you close to the women who sat beside each other thousands of years ago weaving a spectacular cloak together – one working slightly faster than the other. This particular cloak though, also hides a macabre secret. When the cloak first came to Stockholm they noticed that it had some holes in it, the Swedish scholar and archaeologist, Sune Lindqvist, suggested that these were stab marks:

Amica: And because then you can see the, the marks, the holes in it go through the two layers. And I, I have to say that I was sceptical. I thought that maybe it was like when they was digging this up and make this hole, but before this exhibition, they, they let a criminal who working with the, with homicide to look at it and they confirm that it also very sharp object to have go through the fabric and yeah, maybe Sune Lindqvist is right in this but they’re not finding any body, it’s just this cloak put on in, in the bog. So we don’t know the history around it. We just know that in some time someone have stab into it and they are not, like, especially in the chest, they are quite yeah, in the ending of it. So it, yeah, it doesn’t mean exactly that someone have been killed in it.

Jo: No-one knows what the marks mean and the Gerum cloak still guards its mystery close. I find cloaks fascinating, once I started noticing them, I saw them everywhere. So much ancient clothing seemed to be derived from or related to the cloak or cape. There’s barely a painting of the Madonna, Mary, the mother of Jesus, that doesn’t show her wearing her iconic blue cloak. The incredible byzantine mosaics of Ravenna, dating to the 6th century, are studded with cloaks, draped over the shoulders of the three kings arriving at Jesus’s crib, and the Empress Theodora and her attendants wear the most incredible collection of purple cloaks and gold embroidered stoles. These cloaks are rich, elegant garments displaying power and wealth. And at the civilised heart of the ancient world, Rome, there were cloaks everywhere:

Maria Stella: We know that there were many types of cloaks used both in the civic and the military fields. They had different shapes, each with its own name, but sometimes is not so easy to understand the shape from the sources. For example, the Sagum the Laena and the Lacerna had a rectangular shape and was closed in front, near the right shoulder with the fibula. The Paenula had an oval or circular shape, and about knee length with or without hood. For example, the CIrculus had a similar shape, but was shorter. So many kinds of clothes.

Jo: That’s Maria Stella Busana from the University of Padua, she is a Professor of Classical Archaeology, and a fibula is a kind of brooch or fixing pin. In Rome there was much to choose from, but each cloak told its own story and you could only wear the one appropriate for your place in society:

Maria Stella: Cloaks were worn overall by men, but also by woman. The typical feminine cloak was the Palla. The Palla was made up of a rectangle of fabric folded around the body and fasted on the shoulders, with pins, the fibula. The Palla was worn in different ways, either over the head and all around the body, or left draped loosely on the arms when the woman was sitting or in more comfortable position. And the matron wore it when she was in public, so she could cover her head as a symbol of modesty.

Jo: So here the cloak is a symbol of respectable, female, married, status, used to cover the body for modesty when necessary. In Greek and Roman times we are dealing with much simpler, less shaped clothing, more draped – like the famous Roman toga which in some ways sounds like a cloak?

Maria Stella: Hmm. In some respects, yes. In other, no. On the one hand, the toga is the shape of a cloak and was worn over the tunic as a mantle. But on the other hand, however, it was worn in a completely different way from the cloak, which made it a true ceremonial dress. The toga was the distinct element of the Roman citizen. Initially, the toga was worn by both men and women. But starting from the second century BC it becomes the prerogative of men alone, only loose women and prostitutes could wear it to distinguish themselves from Roman matrons.

Jo: So, a properly dressed Roman citizen might be wearing a tunic, a toga and a cloak over the top of all that. The one figure from Roman history who almost certainly will be wearing his cloak is the Roman soldier, who used his in a very different way.

Maria Stella: The clothing of Roman soldier has undergone numerous changes over the centuries. The first clear indication of the cloaks used by soldiers can be traced back to the Republican Age. Already in this chronological phases, there must have been at least two different types. The first called Sagum used by all troops, the second used by generals called Paludumentum.

Jo: The Sagum was an enormously practical item of military equipment, prized by all Roman soldiers – when they weren’t out stealing local cloaks – this was their fighting cloak, they lived in it and fought in it, and if you dropped your shield it could even be used for make do self-defence by wrapping it around your left arm as you fought on in the heat of battle. One Roman soldier and his cloak is still commemorated today all over Europe. In the third century a Roman soldier was riding towards the French city of Amiens when he met a naked beggar on the road. Feeling sorry for him he cut his cloak in half and it to the beggar. A vision later revealed to him that the beggar was Jesus. The solder left the army converted to Christianity and set up the first monastery in France, becoming Bishop of Tours. After performing many miracles, he was consecrated as St Martin of Tours and became the patron saint of France. The remaining half of his cloak became so important to France that is was used as a royal banner in war time and the French kings swore their oaths upon it. The structure in which the cloak was preserved was called a cappella or ‘little cloak’, which comes down to us today as the word ‘chapel’ or little church. In France, Italy and Germany, they still celebrate St Martin’s Day or Martinmas on November 11th. In Venice, the children wear small capes and rush from shop to shop banging pan lids and asking for treats. In Padua, the students wear long cloaks and parade around the town singing and drinking. And the Romans never quite gave up their love affair with the cloak. Their descendants – the Italian army – were still wearing them two thousand years later – although they had a different name:

Vittorio: The tabarro of the Italian troops during the First World War. This model nowadays is called the 1518. And it’s inspired from the troops, of Italian troops, because it was the, the period when Italy was in the First World War, so in 1915 and 1918. As you can see in the inside of the tabarro, we wrote that it’s made in Italy, in pure wool. And there’s really nice other thing, you have to clean the tabarro on the snow because, when the troops were in the mountains and they, they had this tabarro, the morning they cleaned this tabarro on the snow.

Jo: Vittorio is a member of the Zara family, Italian manufacturers who love cloaks and the stories behind them. They make a number of traditional cloaks to this day, close to Venice. One of the cloaks being the 15/18 – a reproduction of the Italian military cloak, that went on being used well into the 20th century: short ones for the enlisted men and longer ones for officers. There is no doubt that the cloak or tabarro has a particular Italian resonance, as Vittorio’s grandfather Sandro knows. Sandro is in his eighties now, he says he loves work so much that he would pay to come in every day to the production house where he keeps his collection of historic cloaks and coats and makes beautiful new Italian and Venetian cloaks. Sandro grew up in a world where everyone, whatever their class, wore a cloak as part of their everyday dress, from the postman to the judge, but then it began to disappear, as he explains in Italian, translated by Vittorio:

Sandro/Vittorio (02:29): clip 1

He asks himself a question that was why the garment that lived and survived for thousands and thousands of years had lost his popularity or its use. And so he asked himself this question, and he was really fascinated by the fact that the tabarro was worn by everyone in every type of citizen, from the nobles to the poor ones, from the merchant to the magistrate. So the word in Italian is ‘transversale’. It was worn by everyone. It could be worn by everyone. And these are the reasons why he decided to try to give life back to garment like this.

Jo: Sandro set about gathering all the information he could about cloaks. One of the things he quickly understood was that a lot of formal dress that is even used today derived one way or another from the humble cloak.

Sandro/Vittorio

We can see in the 1300s in Venice and in Tuscany, the tabarro was more considered as a long overcoat with wide but not long sleeves, like one of the magistrates have nowadays, or the one that the professors of university wear sometimes. And in fact, it was worn by doctors, magistrates and ecclesiastical people. And so, in <laugh>, so in the 13th century, the tabarro was a garment without refinements. It was a more humble garment. And at the end of the 16th century, it became the cloak and it covered the shoulders of the citizens, and the travellers. But only in the 17th century, it began to be used also by the nobles. And in the 1900s, it became a symbol of elegance and distinction.

Jo: Sandro says cloaks were used all over Italy and had different names, but they were particularly popular in the cold areas of the north.

Sandro/Vittorio: It was mostly used in in Emilia Romana, in Veneto, and in the Po Valley, these areas were the areas where the tabarro was most diffused. And in Venice, even before the 1900s the use of the tabarro was generalized also to combat the winter climate, the foggy and the humid that entered in the bones, we could say. And the same applies to Emilia Romana, where everyone rode their bikes to move. And wind and cold did not penetrate that armour, because the tabarro was seen quite as an armour because it defended you from this wind and cold.

Jo: So, your cloak kept the cold out, and it just as it had been a brilliant garment for riding a horse in, so it proved to be an excellent choice for a bicycle, and for the rich men of the Italian region of Emilia Romana what it concealed could be useful.

Sandro/Vittorio: And the landowners of Romana who rode around the plain by bicycle wore the tabarro, under which sometimes they carried some tools to defend themselves, And it is said, and there are some voices that go around about the fact that also Guiseppe Verdi wore in Emilia Romana this tabarro and had a small calibre pistol to defend himself.

Jo: I love that image of the composer Guiseppe Verdi bicycling furiously around Italy in the fog with his pistol concealed underneath his cloak. It gives us a clue as to why highwaymen and smugglers loved the cloak: the sheer volume of the thing made is easy to hide whatever you had underneath. In fact, the cloak became so associated with Italians that they were identified by them when they arrived in America as new migrants in the 19th century. But in the 20th century, Sandro’s Italian fashion contemporaries thought him nuts to try to bring back something so old fashioned.

Sandro/Vittorio: They thought he was crazy. Back in the past, but also nowadays designers try to produce something that is popular. And at that time when the tabarro was disappearing from the common use it was really unreal that the tabarro came back to its popularity. But Sandro was really fascinated from it. It has been really hard. because the fabrics with which you do the tabarro had disappeared. So, there were only the old people, or maybe someone that had a tabarro of their grandparents or someone that was old, we could say. And in this way, my, my grandpa Sandro, decided to call and search these people that had at tabarro, an old tabarro, to get the material, but also to see and to form an archive like the one we have to today.

Jo: But Sandro says he was born against the grain and that’s the way he is. The tabarro that he made is quite simply one of the most elegant garments I have ever set eyes on. It is Venetian in style, made of six metres of super soft felted wool that is produced specially for the Zaras. It is cut from two complete semi circles of rich fabric, which is warm and waterproof. Sandro and Vittorio are both tall Venetians and as they show me just how to sweep the dark folds of their cloaks over their shoulders – this is more like a dance than putting on a piece of clothing – you know that Sandro has created something incredible:

Sandro/Vittorio: So Sandra thinks that the tabarro is a magic instrument. And when you wrap yourself in it, you are only you and the tabarro. Wearing the tabarro is courage, its not caring about the fashion, the social fashion, and what is popular at the moment. The tabarro is synonym of courage because. You don’t care what the society thinks.

Jo: Sandro says you have to find the tabarro that is right for you:

Sandro/Vittorio:

And he was saying you got to try every tabarro and find the one that is yours, and it’s not like the fashion we wear every day. You can’t wear a tabarro if you don’t feel it’s yours. You got to find the tabarro that finds you. It’s a sort of idea where you got to find the tabarro that suits you in the best way. You need to have your tabarro and you can’t wear the one of the others.

Jo: I wonder if Little Red Riding Hood felt the same way about her cloak before she was gobbled up, or if witches on their broomsticks had such a personal relationship with their cloaks. Certainly, they seem to be irrevocably connected to flight in the modern mind. Hollywood heroes like Batman and Superman wear them, and that I think is because they came from comics and illustrations where the cloak easily conveyed drama and movement through the air, but equally it could because of the mystery and anonymity that cloaks symbolize even to this day. Back close to Venice, where the Zaras produce their magical cloaks, sits Katya Simeon. She is the woman at the sewing machine. She has worked there for 16 years and loves making the 1,000 or so cloaks that she constructs every year.

Katya/Alessandro

She has a very personal relationships with them. She actually feels like they are hers and she feels a lot of passion about them.

Jo: Katya believes very strongly that the tabarro choose the wearer and not the other way around – she sees it happen as people try them on in front of her.

Katya/Alessandro

So she’s saying that every single person must feel like the tabarro is theirs. And furthermore, depending on every single person’s characteristics, there are different models which let’s say are more suitable in a way. It is only in the moment when you wear it that you actually feel like it’s your tabarro therefore it is the tabarro that chooses the, the person, not the person that chooses the tabarro.

Jo: Katya’s own cloak is a green 15/18 – I don’t have a cloak – I’m waiting for one to choose me – and that might just mean a trip back to Italy – what hardship! Thank you to the entire Zara family for their hospitality and knowledge, but especially to Vittorio and his brother Alessandro who did the hard work of translating Sandro and Katya’s wisdom. Thanks too, to Sue Day, Amica Sundstrom and Maria Stella Busana for their knowledge.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and produced by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast independent, and free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you extra content every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted by Bill Taylor and me. You can find out more about this episode, and see pictures and videos of how to put on your elegant Venetian cloak at www.hapticandhue.com/listen

We will be back next month with a puzzle: when two different forms of artistry meet in a tapestry who is artist? Come with us as we explore this in the company of some of the best modern weavers in Scotland’s celebrated weaving studios in Edinburgh, and follow the progress of a turning a new piece of art into a tapestry. Join us next time on the first Thursday of the month and until then – thank you for listening and enjoy whatever making you are doing.