Ukraine’s Revolutionary Act of Embroidery:

The embroidery of Ukraine is one of its secret weapons and an incredible defence against the cultural annihilation that has been practiced against it. What it means to be a Ukrainian is powerfully expressed in the complex and beautifully worked stitches that go into decorating their national dress. The knowledge of what each stitch means and the skill to make these shirts is thriving and continues to be passed down the generations. This episode of Haptic & Hue is about how the beautifully embroidered shirts and blouses of Ukraine have endured as a symbol of the country’s fight for existence and have become so entwined with the identity of Ukrainians that some refer to it as part of their genetic code.

Notes:

Lybow Wolynetz is Curator and Librarian at the Ukrainian Museum, Stamford, Connecticut, and also Curator of the Folk Art Collection at the Ukrainian Museum of New York, where she teaches classes in Ukrainian embroidery.

Lucie Heins is Assistant Curator for the Daily Life and Leisure Programme at the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton. She is an embroiderer and a quilt-maker. The museum’s collection of Ukrainian textiles is not currently on display, it is still being processed and will take some time to complete. but, part of the collection, including the embroidered shirts, will be available for viewing from the summer of 2024. In advance of that, anyone interested in a tour of the Orshinsky textiles with a party of between 10-15 people, can request one from the Royal Alberta Museum by e-mailing Lucie on Lucie.heins@gov.ab.ca

Associate Professor Taras Lupul, has been continuing his research at the University of Alberta through the Disrupted Ukrainian Scholars and Students Initiative.

There are some excellent pictures of Ukrainian embroidery and dress on the website for the Ukrainian Institute of Fashion However, this does not appear to have been updated since the war started. For those interested more generally in folk costume I recommend a good blog called Folk Costume and Embroidery, there are a number on Ukrainian costumes including a comprehensive collection of photos and videos of different styles of embroidery from the Zakarpattia region which you can find here.

Lubow Wolynetz

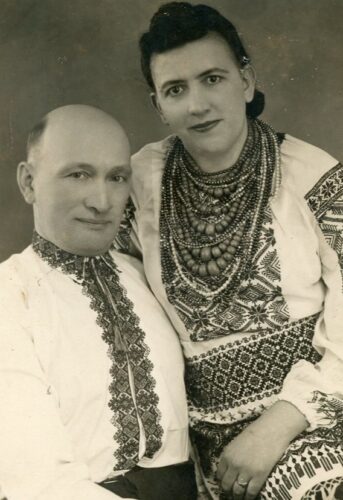

Lubow’s parents immediately after the war

Lubow and her elder sister during the war

Lubow teaching an embroidery class in America

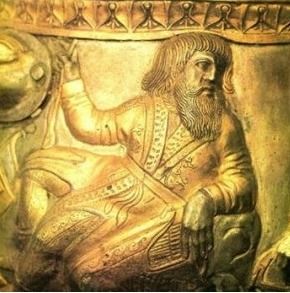

Scythian Gold Cup – Man wearing embroidered coat 4th Century BCE

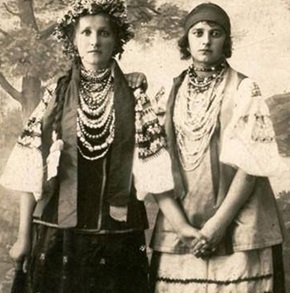

Women in the Donetsk region wearing embroidered blouses, 1924.

Lucie Heins, Acting Curator, Daily Life and Leisure Programme – Royal Alberta Museum

Woman’s embroidered shirt from Bushtyno, Western Ukraine, early 20th century.

Handwoven embroidered blouse from Galicia, Ukraine, circa 1880, from the Royal Alberta Museum

Detail of hand-embroidered blouse from Galicia (1880) – Royal Alberta Museum

Cutwork detail on a blouse’s hem, made in Shypyntsi, Ukraine, 1935, from the Royal Alberta Museum.

Detail of hand-embroidered women’s blouse, made in Shypyntsi, Ukraine, 1935, from the Royal Alberta Museum

Women’s long-sleeved embroidered shirt, made in the village of Shypyntsi, in Western Ukraine, 1935 from the Royal Alberta Museum

Women’s long linen blouse, made in the village of Boiany, in Bukovina Region, 1895 from the Royal Alberta Museum

Detail of beading on a shirt from Boiany (1895) – Royal Alberta Museum

Detail of beading and stitching on embroidered shirt from Boiany, Bukovina (1895) – Royal Alberta Museum

Dr. Taras Lupul

Detail of embroidery on a blouse made in Semenivka, Ukraine, 1930, in the collection of the Royal Alberta Museum.

Script

Ukraine’s Revolutionary Act of Embroidery: How Identity Survives in Stitches

JA: Nearly eighty years ago, at the end of the Second World a little girl called Lubow Wolynetz fled west with her parents after they had endured Russian occupation, Nazi invasion and had then seen the Russians advance again across their country. They, and a number of other Ukrainian families, ended up in a Displaced Persons Camp in Germany.

Lubow: And they all decided, well, you know, we survived. Let’s go and have our photographs taken. But what they did, whatever they had, whatever embroidery, whatever textile they had, they would exchange and dress in it and take photographs only in the Ukrainian outfit or some part of an outfit. And you know, that later when you think about it, they wanted to take the photographs to show that they survived. But how did they, they survived as Ukrainians, not just a regular person. It was so important to them to do that first photograph of, their heritage.

JA: That photograph of Lubow’s parents is an extraordinary one, it’s black and white so we can’t see the colours, these were refugees who had fled just with what they could carry, and yet her mother and father are beautifully dressed in incredibly detailed shirts. Lubow says her mother embroidered every stitch of the costumes.

Welcome to the start of the sixth season of Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles, my name is Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver, interested in what cloth tells us about ourselves and our societies. Often the stories and information that textiles give us are ignored and we lose a whole dimension of human experience. This episode is about how powerful textiles and stitch can be as markers of identity. Clothes don’t just cover us, they tell us who we are and what we believe in. For many of us the folk costumes of old are charming reminders of how our forebears might have lived, But, for Ukrainians their embroidered blouses are a living emblem of who they are, one that is central to their identity.

Lubow: The end of the war, we ended up in a little town in Germany and a few other families, you know, we were just there. And my mother was trying to you know, look through what we lost, what we had. And all of a sudden, she looked and she said that I, I grew up, grew, and I don’t have an embroidered shirt. And for her, it was like a panic, like as if I wasn’t a complete person because I didn’t have the shirt. And so, she called all these other few people who were with us, and she said, I have to embroider her. So she found a piece of cloth. The other ladies helped with the coloured threads. She had enough designs in her head. So, she quickly embroidered something. A German lady lent her the sewing machine. She made this shirt for me. And, and then she, like, everybody relaxed because it was, and maybe at that time when it was done, I maybe didn’t, feel it as, as deeply, but it did internalize in me. And, and this is how I, you know, went along with it. It was such an important act you know, so that’s the deep meaning, that I grew up with.

JA: Lubow was six or seven when this happened – she is in her eighties now – but it has never left her. She came to America when she was ten, straight from the Displaced Persons Camp and all her life one way or another she has been researching and teaching Ukrainian folk art, embroidery and culture. For more than forty years she has been curator of the Ukrainian Museum and Library in Stamford, Connecticut, which houses an excellent collection of Ukrainian embroidery. Interestingly this work is something that originated not with the elite but with the rural poor, and Lubow believes this is partly why it became such a powerful symbol of Ukrainian identity.

Lubow: I think primarily is because Ukrainians as a nation was subjugated by foreign powers for centuries. And the educated classes, small class as they were, were either destroyed or sided with the rulers., the majority of the people, the villager, they were left under their own. You know they had to do something for themselves, with the rich tradition that they grew up with, they wanted to preserve it to, to make a statement that they are different. This is the way we are. And, and so this idea of the identity of your ethnic belonging was very important because you were not free, you have to make a statement somehow you couldn’t fight because there was no way of doing it unless you wanted to be killed: And later on sent to the Gulag. But still, all wanted to make this statement, a political statement. In what way? And the only way they knew, they put on their traditional outfit, well, especially the embroidered shirt, this was their way of making the statement, I am Ukrainian. And for that shirt, they were beaten, they were jailed. They, they were persecuted, but that didn’t stop them because this was the only thing they could hold on to preserve their identity as, as Ukrainian belonging to the Ukrainian nation. And, and this runs to this day, But now, it’s almost international, and many other non-Ukrainians do the same to join with this idea of, of making a statement of our identity to the world.

JA: In Ukrainian embroidery colour and form are both important. There are over a hundred different stitches that combine with drawn thread work and cutwork. There’s some evidence that the origins of this goes back thousands of years. Ukrainians are partly descended from the legendary Scythian horsemen who founded an empire based on Crimea in the 7th to 4th century BCE. In one of Ukraine’s National Museums is a finely worked gold Scythian cup showing two men with what appears to be embroidered edging to their tunics, Lubow herself traces the meaning of the stitches and the emblems shown, far back before the arrival of Christianity in Ukraine.

Lubow: Because Ukrainians were an agrarian society, their whole life centred around the cyclical seasonal changes. They were close to nature which followed through into the Christianity, they were in awe of, of the natural phenomena, and they knew the importance of the sun. especially in springtime, you know, if spring came late, the poor farmers had a hard time catching up and, and having a good harvest in time. Nature is very powerful, and it doesn’t always follow the regularity that men would like. And so, his awe and his fear that some irregularity might occur always was with him. And he wanted to protect himself against these. And he felt that if he applied all these symbols on items that he uses that somehow in some way, they, he would be protected. He would appease nature from its kind of fickle type of, of changes that he cannot control. And he believed in, in that magical power. And he used symbols because the meaning was hidden. Only the initiates knew what it was. And so, so because then if it’s if it’s not visible if it’s hidden in, in this stylization, then it has power, then it has significance. If it’s very obvious, there’s no magic about it.

JA: The most important cloth for Ukrainians was the ritual cloth with its Tree of Life Design:

Lubow: It’s a long cloth. At a very two ends, it would have an embroidered design, and the more ancient one, it would have a tree of life design or goddess protect us, it could be woven or embroidered. You do the outline, but in, in each petal or, or in each branch, you fill it with different type of stitches. And it has that light and shadow effect. And the story is that peasantry saw the colourful embroidery of the elite, because they had all different coloured silk threads, but the peasants had only a red thread, maybe a little bit of blue. So they wanted to have that in their embroidery. And by applying different stitches to fill in that lotus or, or tulip or, or the branch, it gives you such a beautiful shadow and light that, that it looks almost colourful, rich. So that, so those, you had to know all of these little stitches. And in addition, you had to have an artistic eye, how to apply it within, you know, that framework of that, because it had to have a special effect. And though those, those cloths are beautiful, and they were created way back. We don’t know how they looked in the pagan days, but we know that the pagan religion in Ukraine demanded to have religious services in, in forest, in groves. but before you could, you had to sanctify the place and the way you sanctified it is you would hang ritual cloths on the branches of the tree, and then the head chieftan or whoever would start this liturgical service. And, and it was a really important protective cloth for Ukrainians. So, in the pagan days by the entrance door, they would have a special hook and would hang the ritual cloth so that when a stranger enters the home with evil intent, his eyes would fall on the cloth, the red design. And all of the evil intent would be caught into the cloth. And when he entered the home, the evil would not spread that, that this was the belief.

JA: This tradition along with Ukrainian folk music survived the arrival of Christianity, and the cloth gradually mutated into a long cloth to cover your icons with. But the Church in Ukraine also played a role in keeping embroidery alive – the churches needed finely embroidered cloth and they needed help from the poorest in society to provide that:

Lubow: So usually nuns embroidered it in their monasteries, but very often they used talented serf girls to help them with the embroidery. And up until as late as, as late 19th century, they still had serf girls or, or talent local embroiderers. Later on, when Serfdom was abolished young girls helped the nuns embroidered these beautiful s which used silk and, and gold thread, you know, gold embroidery. So, so that type of embroidery always existed.

JA: Serfdom was a form of subsistence farming or near slavery in which the labourer was bound to a small parcel of land generation after generation and obliged to work it even though it belonged to the feudal lord. In medieval times it was prevalent all over Europe, but in Ukraine and Russia it wasn’t dismantled until 1861.

Lubow: Once serfdom was abolished the elite began to see that those semi slave people were human beings, that they are creative, that they’re not just a working horse, but they also have something to say and produce, and to give something positive to society. So, this was like mid 19th century. This, this whole wave of interest into the full creativity began and admiration rose. And then when the academic artists began, like Picasso, you know, began to be inspired by primitive art, by folk art. And to this day, most, at these, most of those Ukrainian artists who were appropriated by Russia saying that they’re Russian like Sonya Delauney and Kandinsky, in their memoirs, they all say it was the Ukrainian atmosphere, the Ukrainian village, the Ukrainian rituals, traditions that they grew up with or saw, even though they were educated, that influenced their thinking and their style and what they put in into their work: So, it’s an interesting credit to the unschooled, talented peasant artists.

JA: Lubow says that this sense of design and beauty contained in the embroidery became an innate characteristic of Ukrainians:

Lubow: They had to beautify things around themselves. Their life was so hard. I mean, the, strict ruling of the seasonal changes of the cycle movement. If they didn’t do the work within that time, it would be a disaster. So, they had to uplift their spirits somehow, and they needed something beautiful to, to create, to, to make it a life lighter, they wanted once in a while to feel above the hard work, above the constant pain, or whatever. And, and they did it by, decorating the home, the clothing, especially the clothing.

JA: The oldest samples of folk embroidery in Ukraine go back to the late 18th century. Before that no-one thought much about it – it was just something the peasants did, but then this great awakening took place and things changed:

Lubow: And only in, in middle 19th century when finally the eyes were open to the society that we have to salvage as much as, because everything will disappear. Scholars in Ukraine began to wander from village to village to collect items, to do interviews and very often, which is very interesting, wealthy families in Ukraine. And very often, usually the women were, you know, interested in, in the clothing and in the decor, and began to collect and write about it. And so we had the first collections of folk shirts or for folk textiles or, or the Easter eggs or whatever were done by wealthy land owner women. And that’s how the museum started privately. And then usually at the end of their lives, they donated it to a national museum. What helped a lot is that the, the Czarist Russian government, like to look up to Britain, what the British did they wanted. And when they created the Royal Geographic Society, Russians did the same, but they had a lot of different ethnic groups. So, the Russian Geographic Society was divided into Kazak group and, and Turkman and so on. And one was called Southwestern Group, and Southwest means Ukraine, and so there were enough Ukrainian scholars who were members of this group, and they were the travellers collecting, writing down and preserving and saving what was still available, although saddened by the fact that they realized that much had been disappearing or destroyed because no one paid attention for it.

JA: At present a different kind of destruction is going on. No-one is sure what the current status of these textiles is. Ukraine has accused Russian of looting more than 30 museums, calling it the biggest art theft since the Nazis in World War 2. Amongst the items that are known to have been taken is beautiful Scythian gold work from the Crimea. Other museums in areas not occupied by Russia have been bombed and burnt down. The focus as ever has been on art and the built environment and it has been hard to find out the status of the textile collections. The Ukrainians call this cultural annihilation, an attempt to destroy a sense of who they are, it is has been practiced against them for centuries and it is something that their embroidery – passed through the generations as living stitches – is designed to resist: Here’s Lubow again:

Lubow: it’s like learning to walk or learning, to do personal chores. It was something natural. You were a certain age. My mother or any other mother would take a needle, a piece of, of sack cloth in the beginning and start teaching the child, the first stitches. Of course, not everyone took to it quickly, you always had rebels. But, on the whole, every girl knew at least the basic stitches and understood some of the motifs, some of the applications, some of the compositional arrangement. You had to show your ability that you’ll make a good housekeeper that you’ll take care of your family.

JA: And after you were married, Easter was the time when you went to church and showed off your new embroidery.

Lubow: And people went looking, and naturally, you know, how women are criticizing all, she didn’t do it this well, or she didn’t do any, a new one. You had to show at least if you didn’t do it for yourself, you had to do it for your children and your husband to show off that you are a good housewife that you manage to be creative, and manage to do all of this in the winter months so that Easter Sunday, you could show off. And then, interesting that in Western Ukraine, they say ethnographers loved to go on Easter to the different village churches, because then they saw that beauty and they could photograph or draw all of this novelty for them, it, it was beautiful. But even like Western Ukraine, when it finally, after World War, I came on the Polish rule, Polish scholars used to come, and they loved to go to these village to show, because they understood the beauty, the creativity, and they appreciated it. Even well, scholars would, you know, it’s the politicians who do not <laugh>, right?

JA: Ukrainians managed, against Russian opposition, to preserve their embroidery as a living tradition especially in remote country areas well into the 20th century, although often at great risk, especially if they included blue and yellow, Ukraine’s national colours, in their work. In the 1960s and 70s one of the first signs of active dissent against Russian rule came from the students in the cities who began singing Ukrainian carols – these are pagan songs celebrating winter– they have nothing to do with Christianity but they were banned anyway:

Lubow: These winter songs are one of the oldest oral traditions that we inherited from, from the villages that preserved it. And the, the communists forbade this carolling. And one of the first movements of dissent were young students, young professional journalists, artists all of a sudden around Christmas time would dress in costumes if they found in the grandma’s, and they would very often be arrested, reprimanded. Some of them later on naturally were sent to the gulag if they wrote poetry and died there. But, but this was one of the like first open protest in, in the end of sixties and seventies, the beginning of the return of, of the carolling tradition.

JA: The bravery of these young Ukrainians was incredible and it confirms the power contained in simple songs and stitches. During the 19th and 20th centuries millions of Ukrainians emigrated. They went east, west north and south and they ended up all over the world. Lubow says in her experience all Ukrainian migrants took embroidery with them when they left:

Lubow: It was like, an important part of themselves. They needed that. It, it was that route that they didn’t want to abandon, because it was part of their identity you know, the national consciousness was there and they needed that whatever they went to the farm, , they know they’re going to adopt a different country live in, in a different style, maybe. But they still wanted to keep this, this identity of their roots, of their ethnicity in some form. And they did it by taking and bringing with them some item one or two or many and preserving it. Because that made them complete. And, the children watching the grandparents’ benefited from it because they developed that affinity, where they came from why they came, and what they bring with them. Not money, not, not gold, not silver, but something much more tangible of their personal completeness as a as a human individual of certain ethnicity.

JA One of the places Ukrainians settled was the province of Alberta in Canada. Today there are more than 300,000 people of Ukrainian descent in Alberta including 30,000 who say Ukrainian is their mother tongue. Many of them came from the area around Bukovina and Galicia in Western Ukraine. They first started arriving in Canada in the late 19th century in response to the offer of free or very cheap land in the Prairie provinces:

Lucie: And there was a focus on the Ukrainian population because they were farmers, they were used to the climate, it was similar to Northern Alberta at the time. They were considered very hearty people. I mean, it brings to mind this archival photo that I have seen a a photo that was taken here in Alberta where obviously the farmer did not have any, animals to pull the plough. And in this photo, you see the farmer behind the plough, and approximately 12 Ukrainian women pulling the, the plough in order to be able to sow seeds. So, to me, that really represents sort of, the hardiness of, the farming community that came from Ukraine.

JA: That’s Lucie Heins who is the acting curator of the Life and Leisure Programme at the Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton. As well as their strength and energy the Ukrainians brought their textiles with them:

Lucie: A lot of table runners place mats a lot of kilims, we know them as, as rugs, but these were rugs that were placed on the walls of the houses, not as decoration, but to really keep the warmth in. Of course, at the time that they arrived in Alberta, we didn’t have, home heating or central heating. It was, you know, wood stove. The stove would stop heating usually in the middle of the night. And so, the rugs on the walls would help contain the warmth in, in the house. And many who came also they started out in sod houses, sod huts. And so, this is just made out of dirt and half built in the ground. They’re very small. They’re cold and damp. So, they brought what was going to keep them warm.

JA: But as well as practical textiles these families brought with them the textiles of their Ukrainian heritage, highly embroidered, hand spun and hand-woven linen shirts and blouses handed down through their families: and the reason we know this is thanks to a farmer from Ontario. Peter Orshinsky’s grandparents migrated to Canada from Ukraine in the early twentieth century and he grew up in Ontario speaking Ukrainian, although his mother’s family came from Alberta.

Lucie: So we do know he went to Alberta for the first time in 1959. So, and then in the sixties, the seventies and the eighties and the early nineties. He was going to Alberta probably yearly. To him, Alberta was his, his Ukrainian home. That’s how it was, the, the home of his heart as he puts it. And where he felt, you know, he was amongst a huge population of, of Ukrainian people where I, I get the impression that when he lived in Ontario, it wasn’t sort of a, a block of a region where many Ukrainians lived. But I think he just really felt at home here in Alberta, and, and he felt like it was his Ukraine.

JA: Peter was a born collector and he started travelling from household to household talking to the older women who had textiles to show him and stories to tell him.

Lucie: He became known in the area where the Ukrainian population were living at that time. And they were living, for the most part in close proximity to each other, although there were some that were in southern Alberta. But he focused mostly on the population, just northeast of Edmonton, because that’s where his mother’s family was from. So that was his initial connection. And from there, he would’ve been introduced to, other people that were not his relatives.

JA: Down the years Peter Orshinsky collected over a thousand items, not all are textiles but of those that are – nearly all were made in the Ukraine and had been carefully looked after for decades in Canada.

Lucie: So, I would say 98 to 99% of the textiles in this collection came from Ukraine. Just a small percentage were actually made in, in Canada, in Alberta. The earliest garment that was collected dates back to 1865, which I was totally surprised that people would have. And I believe that many of these garments, because they’re very loose fitting, they’re not tight-fitting garments, they were, were passed down from one generation to the next to be worn at special occasions. And that’s why some of these we have quite a few garments that are from the 18 hundreds.

JA: The amount of work that went into creating these shirts and blouses is immense as they were handmade from start to finish:

Lucie: The earlier ones from the 18 hundreds are primarily hemp. They’re very very like very sturdy, very strong, also coarse, somewhat, it’s not a, a refined hemp fabric. I mean, it is definitely home spun. And, you know, it would take them a year to make a piece of hemp fabric from, the growing of the crop and then, the harvesting and retting of the fibres in order to be able to to spin them. So, then they had to, to spin the fibres into, to a yarn that they could weave. And so it was not quite as refined as machine spun hemp as we would see today.

JA: And they have a character and a quality all of their own:

Lucie: But it gives you an idea of what life was like. You didn’t have fast fashion. You didn’t, you know, <laugh>, I mean, it wasn’t always easy to, or could one, afford to always purchase beautiful clothing and especially anything like the Ukrainian shirts, whether men or, or women’s shirts that are beautifully, beautifully embroidered. And I am an embroiderer, and like, it, it just boggles my mind the amount of time that it would take to make these, garments. They’re very special and that’s why people hold onto them for sure.

JA: These are pieces of clothing worn next to the skin made by your mother, grandmother, or great-grand-mother. They contain the code of your culture and the badge of your region. They encapsulate your past, and carry in their stitches the sense of what it means to be a Ukrainian into the future. They were certainly garments designed to last.

Lucie: They are in very good condition. All of the items that we received, there are very few that are in, in poor condition. I think a big part of that is because the garments themselves were made for special occasions, so they were not worn as often. And perhaps the reason we don’t have many of the very plain garments is because they were worn out, they were passed down, and because it takes so long to make these garments by hand you know, they just didn’t toss them out, if there were holes, they were refashioned into smaller garments for children. So, they were used up. Then they became maybe, you know sort of a table runner, you start cutting them down and use all the good pieces as much as possible.

JA: The Orshinsky collection came to the Museum nearly 20 years ago, and although it has been carefully stored since then, no work had been done on it. However, last year Lucie started researching it. She was prompted by the war in Ukraine, but also by local residents with Ukrainian heritage who wanted to see and understand more about their culture:

Lucie: And so that really, gave me the sense that this is important to them, and these individuals are, are descendants of Ukrainian families that, were the early settlers to, to Alberta. They felt they needed to feel now being connected and getting to know more about their culture was even more important now that these terrible things are happening in, in Ukraine. So I think it, it’s sort of elevated in everybody’s minds, whether you were a Ukrainian descendant or for us at the museum who has a Ukrainian collection that we want them to you know, I mean, we, we always care for everything that we comes into the museum, but I think there is this urgency to ensure that it becomes accessible.

JA: One of the people who has is helping her to do that is part of a new wave of Ukrainian settlers to Alberta. Taras Lupul arrived in Edmonton with his family on an Emergency Travel Programme shortly after the Russians invaded Ukraine:

Taras: Even now, after February last 2022, in Alberta came about 30,000 new Ukrainian displaced persons. But now Ukrainian language is everywhere in Edmonton.

JA: Like many other Ukrainians, Taras has cousins in Alberta who were there to help him. He is an Associate Professor at a Ukrainian University in the field of History and Political Science. In Canada he has been carrying out a project with the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies called Making Home in Times of Peace and War and speaking to the new Ukrainian arrivals:

Taras: And I had about 50, the interviews, especially the Ukrainian woman and mothers and their kids who came from Eastern Ukraine, Northern Ukraine, but from not many, but from Western Ukraine.

JA: And the question he asked them was what did you bring with to Canada that reminds you of the home you left in Ukraine?

Taras: And probably half of them said me one thing is embroidered t-shirts for me or for, for kids, probably just, just one thing. Some of them brought the key of her parents or grandparents even I brought the, Key from my parents’ house in <laugh>, my, in my native village. Yes. But yes, it’s a deeply feeling of existence since it’s a sense to be involved in eternity. In eternity or so this part of this community self- identification and community identification.

JA: We don’t know what has happened to the textile and embroidery collections in museums in eastern and southern Ukraine. It will take a long time for us to find out. But we do know that because Ukrainians value their embroidery as a such a deep part of their culture, they continue to carry the pieces and the knowledge of how to create them, to every corner of the world. There are diaspora collections in many places, not just Canada – and these are important – they ensure that whatever happens in Ukraine and despite war and hardship – these are stitches, just like the music of the Ukrainian National Anthem that can never be undone.

JA: Lubow Wolynetz came to America directly from the Displaced Persons Camp when she was 10, her parent woke her before dawn as they approached the American mainland.

Lubow: And they woke us up like before four, so we could see the Statue of Liberty. And so my mother asked me, what do you want to wear, when you come, in American land? and I said, I want to wear my embroidered shirt. And it was not that somebody prompted, I don’t know why I said, but, you know, it’s just like part of you that, that becomes it’s natural, you know? And so, I stepped on American soil in my shirt, <laugh>.

JA: Thank you to Lubow, Lucie and Taras for their time and knowledge of Ukraine and its textiles. Haptic & Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast independent, and free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you extra content every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted by Bill Taylor and me. You can find out more about this episode, and see pictures of some of the embroidery we have been talking about at www.hapticandhue.com

We will be back next month with an episode on a piece of clothing that has a good claim to being a universal garment. It is thousands of years old and yet it featured on the catwalks this year. Beloved by highwaymen, superheroes and witches on broomsticks, it was worn by the soldiers of the Roman army and the hobbits in Lord of the Rings. Join us next time on the first Thursday of the month and until then – thank you for listening and enjoy whatever making you are doing.