The Language of Thread:

This episode of Haptic & Hue tells the little-known story of how two separate sewing schools on different sides of the Atlantic gave women all over the world a new life of economic independence, social status and personal power. One of these education programmes took the Singer sewing machine into every corner of the globe. The other, a ground-breaking teacher training college in London, had an impact on the lives of millions of girls all over the world.

Haptic and Hue uncovers some of the hidden and un-regarded history of stitching and needlework. This was a universal part of women’s lives that is in danger of being lost because it has been almost entirely overlooked. It looks at how women, and some men, from different countries and cultures around the world, were taught to use a needle, and later a sewing machine, to earn a living, and to sew for themselves and their families.

The people you hear in this episode are:

Vivienne Richmond who describes herself as a textile historian, maker and mender. You can find her website at https://viviennerichmond.com/. You can find her book: Clothing The Poor in 19th Century England in the Haptic & Hue UK Bookshop and in the Haptic & Hue US bookshop.

Vivienne also wrote a wonderful booklet about the Whitelands Samplers to go with an exhibition of them that was held in 2016. You can download it from the bottom of this page on her website. She is also Co-editor in Chief of the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of World Textiles which comes out next year.

Nina Sargaço is the founder of an extensive collection of the technical and methodological aspects of vintage and antique needlework. She collects and matches sample pieces she finds with patterns and instructions in the original books and magazines. She has an extensive collection of how sewing was taught and its practice, as well as its impact on women’s lives in South America. The collection is a private one, but she welcomes visitors with a genuine interest in understanding more about this subject. She has no website but can be contacted through Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/colecao_ninasargaco/

If anyone is interested in the magazines of this period then the Hathi Trust has an online collection dating from the 1880s onwards of The Delineator Magazine which was produced by Butterick showing women how to make the patterns of the day for their families.

Thanks also goes to Gemma Bentley at Roehampton University who made it possible for us to see the archive and explore it at our leisure, and also to Jo Teague, who after listening to me talk about Whitelands for months marched me off there one cold winter’s day.

Finally, thanks goes to Louise Kerr, of Resonance Voice Training who played the part of Kate Stanley.

Vivienne Richmond and Jo Andrews in the Whitelands Archive.

Child’s Cutwork Dress, Whitelands Archive

Details of Handstitched Cutwork

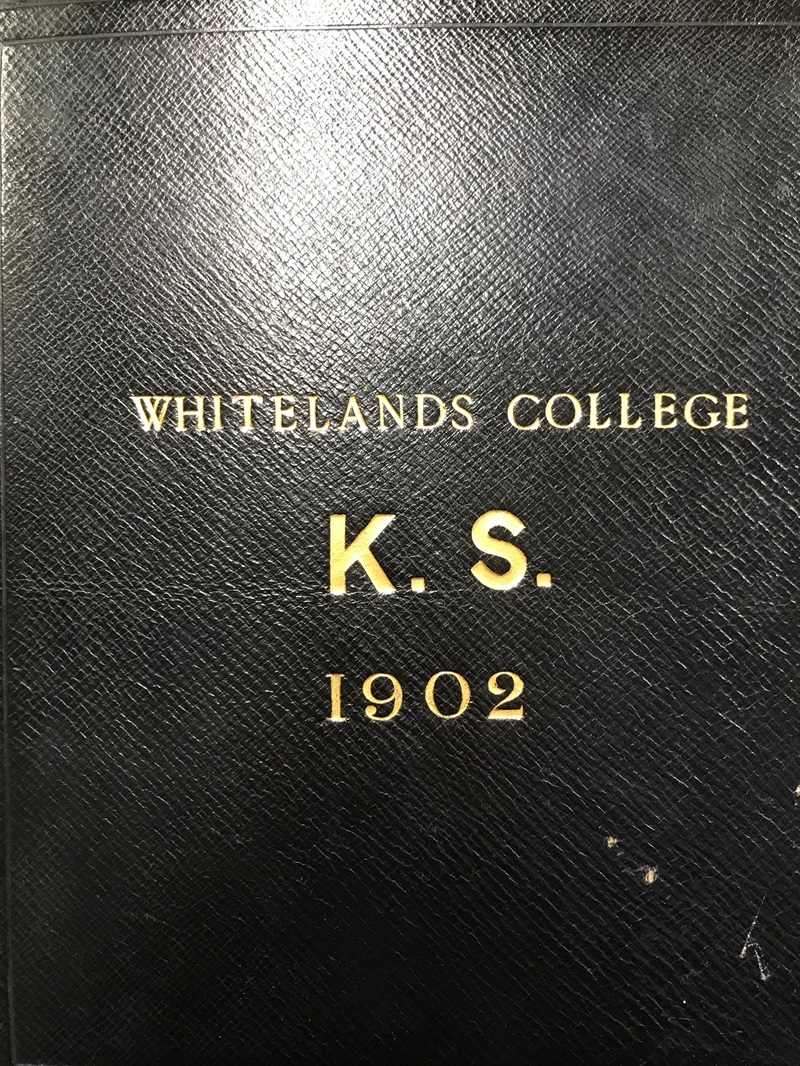

Kate Stanley’s Book, Whitelands Archive

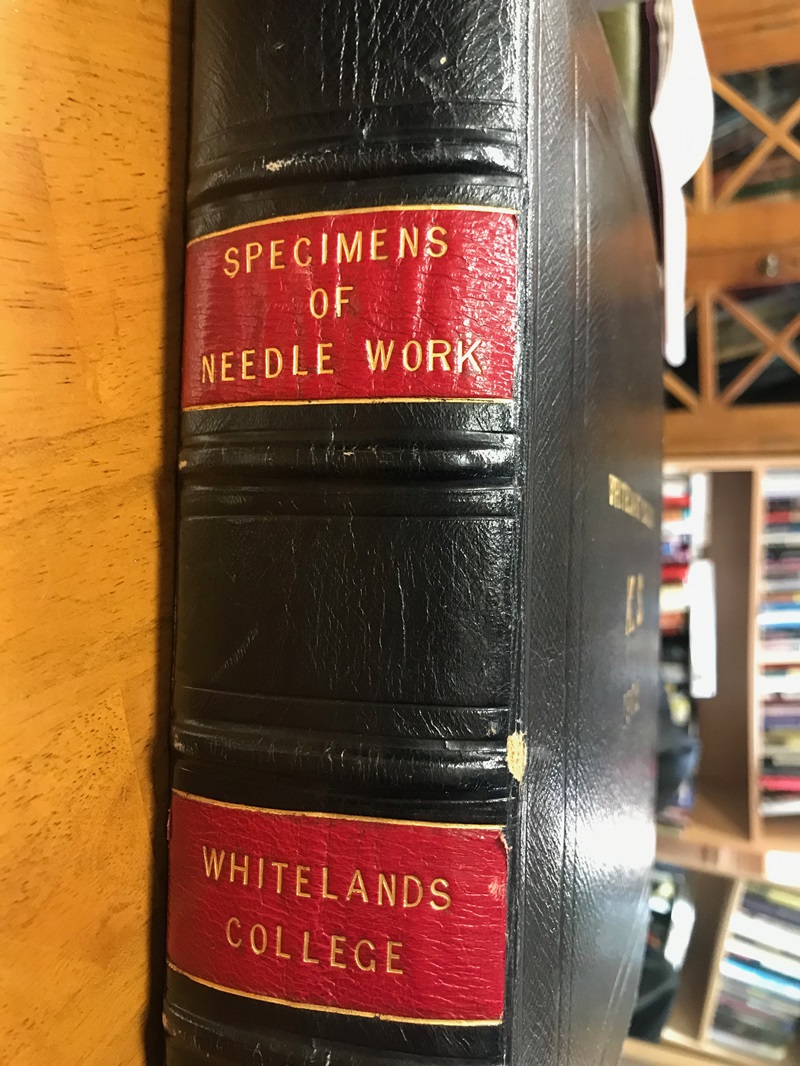

Spine of Kate Stanley’s Book of Samplers

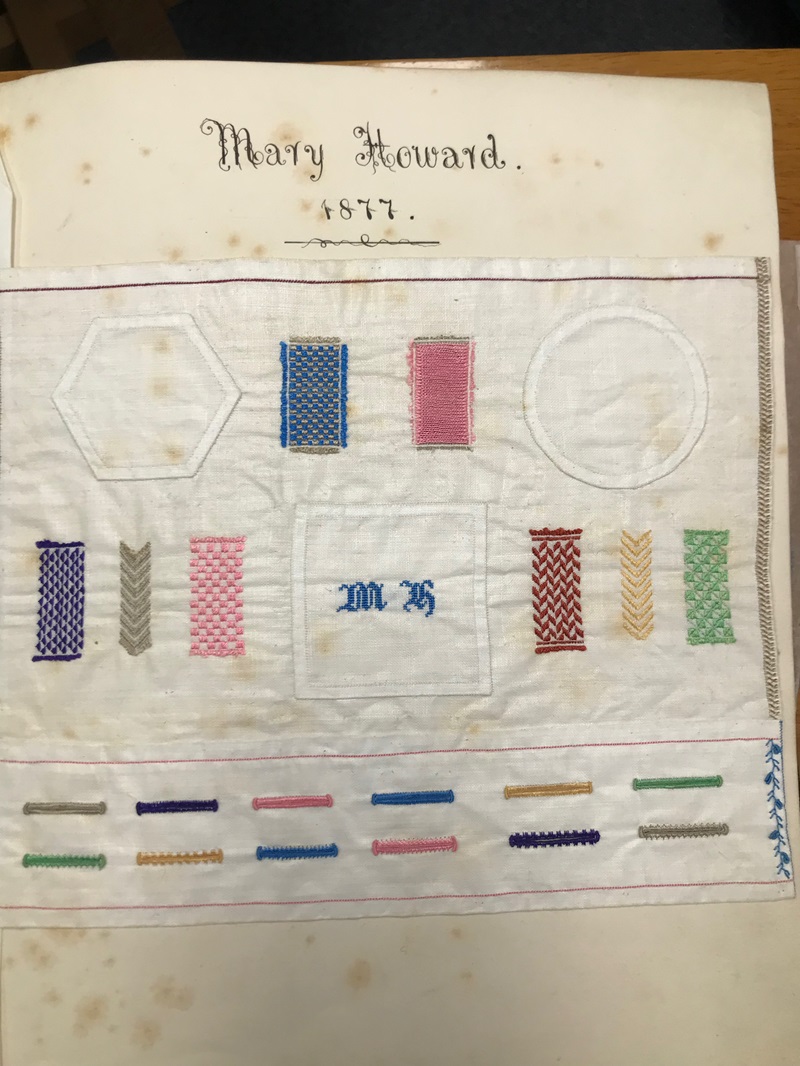

Mary Howard’s Sampler, Whitelands Archive

Detail of Handworked Damask Darning – Mary Howard Sampler

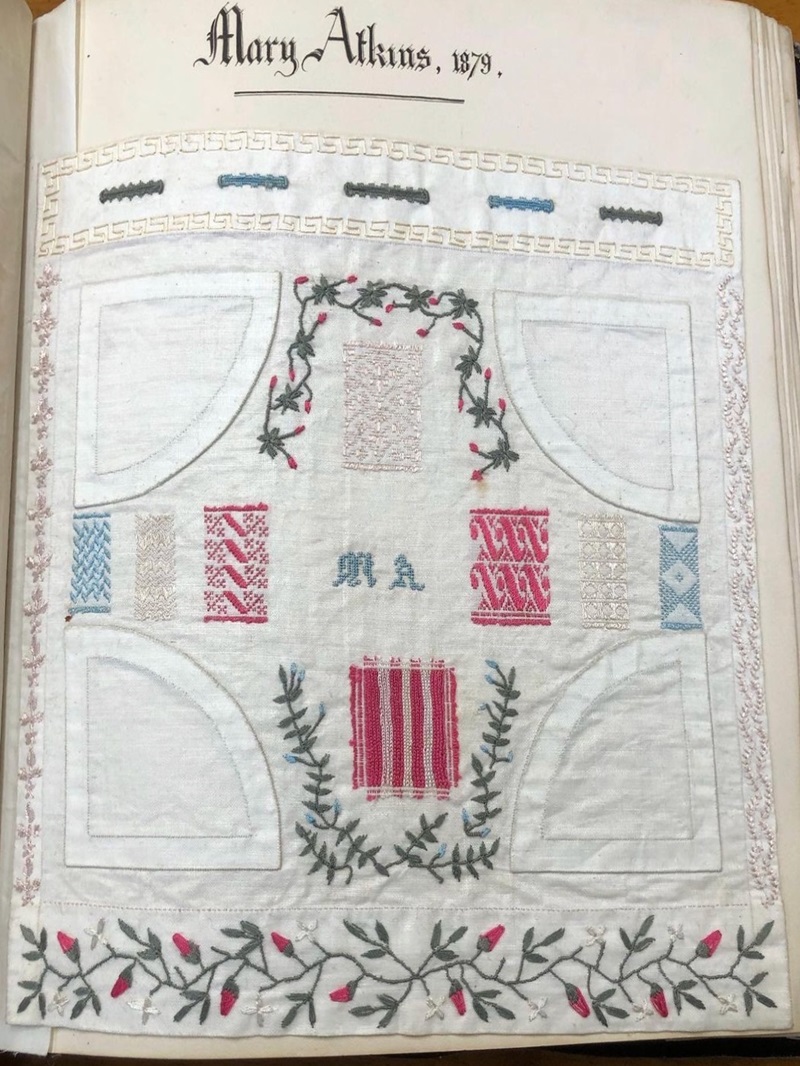

Mary Atkins’ Handstitched Sampler, Whitelands Archive

Ada Blanche Taylor’s Handstitched Sampler, Whitelands Archive

Stocking Web Darning, Whitelands Archive

Nina Sargaço in her Collection, Sao Paulo

Nina’s Collection of Sewing Methods and Samples

View of Nina’s Collection

Singer Sewing Machine in Nina’s Collection

Graduate of Sewing School, Sargaço Collection. Note the Scissor Garland

Unknown Graduate of Sewing School, Sargaço Collection. Note the Scissor Garland

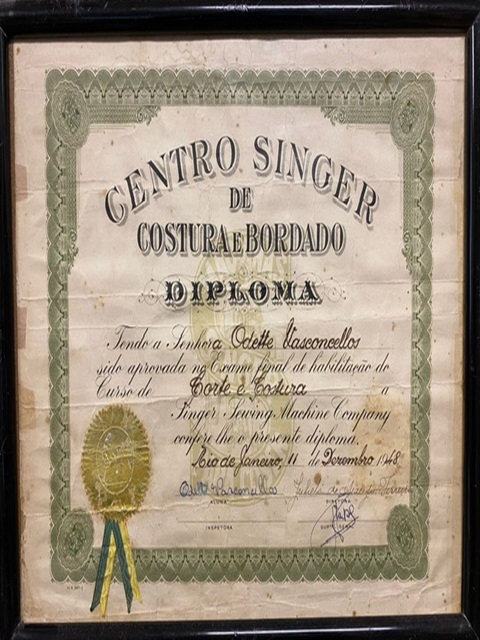

Graduation Certificate – Sewing and Embroidery Singer School, Rio de Janeiro, 1948. Sagaço Collection

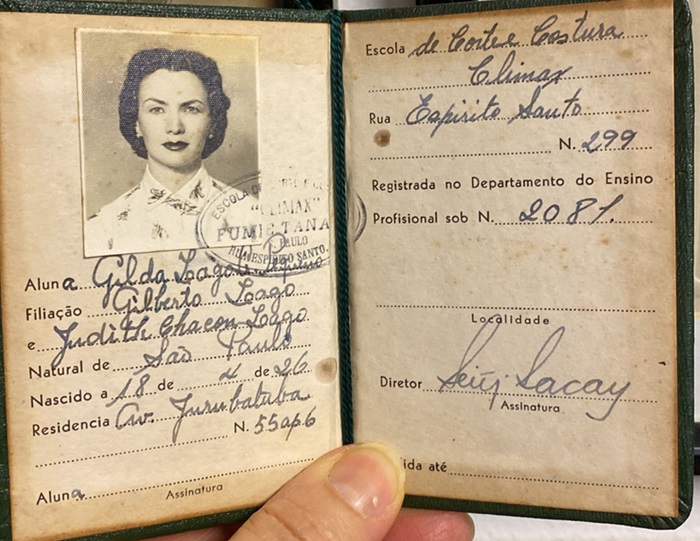

Gilda Loago – State Registered Seamstress, Sao Paolo, 1926, Sagaço Collection

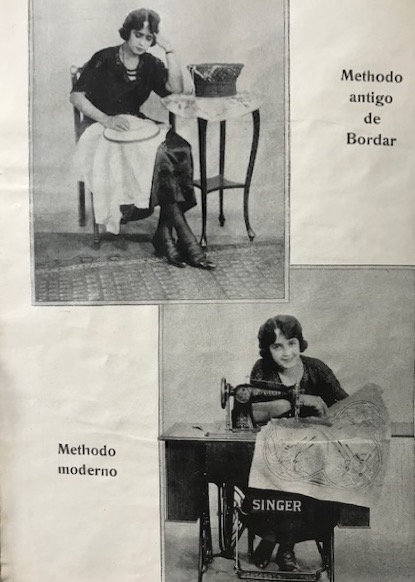

Portuguese Advertisement for Singer, Sargaço Collection

Singer Advertisement for Embroidery Course, Peru, 1920s. Sargaço Collection.

Script

The Language of Thread – Why Sewing Matters and How It Was Taught

JA: If you are listening to this podcast with any kind of clothing on then you will understand why stitching is important – someone sewed your garments. Maybe you did it yourself, but it is more likely that one of the millions of women and some men who are employed around the world in the vast textile industry used a machine to do it. Stitching is a language of its own – a rare language that unites humanity rather than dividing us – it rises above differences of ethnicity, geography, ancient hatreds and divisions. But its story is in danger of being erased, because very few have thought it important enough to collect or preserve the record.

This episode of Haptic and Hue is about the impact two separate sewing schools on different sides of the Atlantic had on women all over the world. One of these education programmes took the Singer sewing machine into every corner of the globe. The other was a ground-breaking teacher training college in London that affected the lives of millions of women around the world.

Welcome to Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles, my name is Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver, interested in what cloth tells us about ourselves and our societies. Often the stories and information that textiles give us are ignored and we lose a whole dimension of human experience. This podcast is about trying to restore that.

In the 1830s the British Government began worrying about education, and not before time, at least a half of women and over a third of men were illiterate, so it started to subsidise the building of elementary schools. What was needed then were teachers to staff these new schools, and in 1841 Whitelands College was set up in London. This was the first women’s teacher training college in Britain and its purpose was: “to produce a superior class of parochial Schoolmistresses.”

It still exists today – although its mixed now and is part of Roehampton University in southwest London. At the heart of the old Victorian building there is a chilly and lightless strong room. In it there are boxes of intricate needlework, samplers demonstrating perfect patterned damask darning, tiny handstitched children’s clothing, beautifully turned out smocking and buttonholes, a cutwork child’s dress each hole handstitched, minute knitted socks and handmade infants’ shirts. These rarely see the light, and are all but forgotten, but along with the records that Whitelands collected about their student teachers they have something important to tell us about how girls were educated and why needlework was central to that.

Vivienne: Needlework was seen as, arguably the most important skill that a woman could have. So, for working class girls, the expectation was that working-class women would make and maintain all the non-tailored clothing for their families, as well as all the household linen. You’re talking when Whitelands opens, if working class people want new clothes, they don’t go to a shop and buy new clothes, they buy fabric and they either make it themselves, or in the case of men’s tailored garments, they have a tailor make it. So, needlework was an incredibly important skill for homemaking. It was also important for employment because the expectation was that huge numbers of working-class girls would become domestic servants and they would be expected to make and maintain items of their employer’s clothing. But there was also a moral aspect to this that needlework was seen to instill in women the sort of feminine virtues of discipline patience, obedience. It’s no exaggeration to say that if you were a woman in the 19th century and you could not sew you were not a complete woman.

JA: Vivienne Richmond is a historian of non-elite dress. She knows the Whitelands Archive well and has written about it. She met me there one cold winter’s day to give me a tour of it and explain why it matters.

Vivienne: Well, well, gosh, where to start The Whitelands archive is particularly good because not only does it have all the, the material culture, but it also has all the records that, that tell us so much about these young, young women where they came from, where they went to after they graduated from Whitelands, what the curriculum was, how they spent pretty much every minute of every day. And that’s really unusual because it’s working class history and working-class history. We so rarely have such a complete picture. By the time people began to think that working-class history <laugh>, the history of the majority of people was worth looking after or looking into, so much of the record had been destroyed. So this is really great because it gives us such an insight: And beyond that, it’s also women’s history, working class. Women’s history is even more obscured by loss and neglect than working class men’s history. So if we want to know about the way that women’s lives could change in this really vital period of early industrialization, this is the opening up of a profession for women we are talking about a practical skill here in one sense, but the curriculum was very broad. So, alongside the needlework, these women were doing languages, history, geography, art, maths science. This was a, a professional training that gave them status and broadened their expectations enormously. And, and this archive shows us that so clearly this transition, this opening up of possibilities for working class women at this really, really sort of volatile period in history.

JA: The young women who arrived at Whitelands College to be trained as teachers were being offered an incredible opportunity for those days. Their places were paid for by scholarships or their fees were later taken out of their salaries in their first postings. They often came from poor backgrounds.

Vivienne: We know that they came from predominantly sort of skilled, semi-skilled working class parents. We know this because the archive contains a huge ledger, which has all the details about when the students entered, what their parents did, what students were doing before, where they went on to after they graduated from Whitelands. So, we can see they came from these semi-skilled or skilled working class. But there were occasional orphans who we don’t know what their parents did.

JA: They were women like Josephine Patterson who was 18 when she arrived at Whitelands in January 1887. She was an orphan from Gateshead in the North East of England. She was charged £12 for her two years of tuition and board which she would have paid back out of her first job, at a school in Leeds. Or Ada Blanche Taylor who was 20 and the daughter of a printer and stationer from Scarborough when she came to Whitelands in 1893. She too paid £12 for her training which she completed in 1895. Sewing skills and needlework formed a huge part of the curriculum Josephine and Ada were taught. They were examined in both years and it’s clear that they could not hope to become school mistresses without a very high degree of skill in hand-stitching. The work that remains in this archive is of an almost unimaginable quality, and at the centre of that is a leather-bound book of immaculate plain stitch samplers:

Vivienne: So, in 1877, a woman called Kate Stanley became the head governess at Whitelands. She had herself been at Whitelands as a teacher beforehand, and she began teaching at Whitelands in, I think it was 1859, and then became head governor. And she retired in 1902. And under her governorship, needlework took on this new elevated status at Whitelands. And she was also championed by John Ruskin, the leading Victorian art critic in arts and crafts movement promoter. And the students, when they graduated, at the end of their one or two years, mostly two years, they produced these darning samplers or samplers of needlework. And this album is an album from 1877 when Kate Stanley becomes the head governess until 1902 when she retires. And it is an album of the very best examples of these, what we might call graduation needlework, samplers throughout those years. Each page has a different sampler. They’re all about somewhere around 20 to 30 centimeters square. And each one is, has at the top, it has the student’s name, and it has the year that it was produced. And it shows you the development of the needlework styles throughout those 20 odd years that the album covers.

JA: Kate Stanley was the daughter of a plasterer and slater and she was fitting her students for a life in which they would instruct class after class of very young girls to become proficient at sewing, not just to keep themselves and their families clothed but also to fill the ever-present need for seamtresses, milliners, dress-makers, and of course household servants:

Vivienne: Okay, so this page, this is a sampler by Mary Howard in 1877, and it’s representative of all the earlier ones. So, it’s got three white patches on it. So, there’s an example of how to sew a hexagonal patch, a circular patch, and a square patch. And then it’s got 3, 6, 7 examples of what is called damask. It’s got one super fine example of stocking web daring. And then it’s got 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 button holes of various styles and a very little bit of very decorative stitching along the side. Oh, and some herringbone stitching as well there. And in the middle are Mary Howard’s initials embroidered and it’s interesting because the only reason that these girls were learning how to do these initials was not to show that they had made the sampler, particularly, it was so that when working class girls became domestic servants, they could mark their employer’s laundry with the employer’s initials. And so, when it went off to laundry, they’d know who it belonged to when it came back. And so, when I describe it as these bits of darning and some patches and a couple of initials and some buttonholes, it sounds very unexciting, but I find it very difficult to find the words to express just how marvellous this stitching is. It is absolutely minute. I know with the aid of a magnifying glass, I was at one point able to count up to 30 stitches per linear centimetre. It’s, it’s just marvellous, marvellous work.

JA: And although to our eyes the samplers look anything but plain, they are very far from the decorative samplers we see made by children in wealthier families in North America and Europe. They were making samplers with some degree of freedom about what they sewed – At Whitelands there was a strong moral prescription against anything fancy.

Vivienne: Absolutely. So the idea was that you would teach working class girls only to do the kind of sewing that is well, useful and necessary was a, a common phrase, or the useful and necessary stitches to make plain utilitarian garments, and plain utilitarian household linen. embroidery was seen as the pastime of wealthier girls and women, working class girls should not have time to waste on embroidery. If they had time to spare, there was surely some work they could be doing instead. And when the government did make education compulsory and free and funded it completely, and they published from the 1870s the schedules of needlework instruction. So, basically the curriculum for needlework in state funded schools, which were attended exclusively by working class girls, it’s specifically for bad the teaching of fancy work or which, which is essentially embroidery. So they were not allowed, they were specifically forbidden to learn how to embroider in school because

Jo A: This would be getting above themselves.

Vivienne: Absolutely getting above themselves. And really, as I said, if they had time to embroider, they were wasting time. They had, they, they should be finding, you know, more work to do. There was plenty of work.

JA: The teachers from Whitelands, and the other teacher training colleges, that were set up in Britain, had an influence far beyond the small parochial schools of the country.

Vivienne: So, the Whitelands’ teachers were, were trained, and off they went into the world. And, and I do mean the world, these teachers, they taught in over half of the schools in England and the teacher training colleges, and they went off to teach and head schools and colleges around the Empire. So, these working-class girls who, you know from their childhood would probably have imagined that the, the physical world that they were to visit in their lives would be quite circumscribed, could find themselves in India or they might find themselves in, any outpost of the British empire and beyond. America, there’s quite a lot went to America, for example. They would go there and teach. So, it opened huge worlds for the teachers themselves. But it also meant that all this ideology that was put into the girls’ minds through what they learned at Whitelands and often through the needlework, was exported around the British Empire, and to all those children across the Empire, who the Whitelands teachers were eventually to teach.

JA: Josephine Patterson, the orphan we met earlier, who arrived at Whitelands in 1887, taught at schools in the UK for four years and then in September 1893 she sailed for Shanghai where she lived and taught for more than 20 years. And Ada Taylor’s first job was at the Ecole Normale in the town of Tulle in the Corrèze in France. Others have addresses in New York, India, Canada and beyond, passing the methods of stitching they learnt at Whitelands and the moral attitudes attached to them, down the generations. In 1883 Kate Stanley wrote a book called Needlework and Cutting Out. By luck I found it in second hand book shop. Here’s how she starts:

Kate Stanley: “Within the last few years, Needlework has taken, and wisely taken, a much more prominent and important place than it formerly did in the Education code. And as the children in our schools are now examined in the subject individually, it is necessary that they receive special teaching to prepare them for the test. The need for some guide in giving such lessons made itself felt among my own pupils, and induced me to comply with the request that I should write a series of papers for the Schoolmistress.”

JA: It starts with Elementary Stitches and Sewing On Buttons and Tape Strings and ends with cutting out and making up A Woman’s Gored, Flannel Petticoat, and as ever the moral purpose of this work sings out:

Kate Stanley: “It is most desirable that girls should be taught to be good thrifty housewives, and a critical test of household management is the state of the linen. It often happens that sheets and pillow cases are torn at the wash, or by being caught on hedges or bushes in taking them in after drying. Girls should therefore be encouraged to learn how to repair such damages so as to make them as little observable as possible.”

JA: It makes you wonder when washing lines arrived, but it also helps me understand why my failure eighty years later to master the basics of this subject in primary school was seen by my teachers, and my grandmothers, as signalling something worse than mere incompetence. Miss Stanley also includes in her book examples of the needlework exams of the 1880s for girls – here’s one for 7-8 year olds.

Kate Stanley: “To fix and work a sew and fell seam of 5 inches, in cotton of two colours, so as to show a join in the cotton, both in seam and fell. Or cast on 12 loops and knit, 12 rows, ribbed, purl, and plain and afterwards cast off. Or pleat 7 inches into 6 pleats and hem into a band of 3 inches.”

JA: Miss Stanley would be horrified to know that a recent survey suggests half of adults in the UK would have to ask their mother for help just to sew on a button, although many of them wish they could do it themselves. When Kate Stanley published her book – almost every woman in the country, apart from the wealthiest, would have had to know how to sew by hand as a matter of course.

This is even though Isaac Singer had patented his sewing machine in 1851. But it took time to take off. It wasn’t until the 1860s that machines began to be manufactured in any numbers and even then, priced at $100, they were much too expensive for ordinary American families. It was really the 20th century before sewing machines began to change people’s lives around the world, and that had a great deal to do with the Singer company’s realisation that they needed to teach people to use them.

Nina: So as soon as the sewing machines was ready, Singer started putting out the Singer Centre, which was a shop, where it would sell everything, the sewing machine, the oil, the needles. They were beautiful, the architecture plan was all the same worldwide. Some more fancy, like the one in Moscow, it’s absolutely an Art Nouveau building. It’s like a palace. It’s something, I mean, it’s a chin dropping building.

JA: Nina Sagaço is a woman on a mission. In Sao Paolo, in Brazil, she has established something that no-one else has thought to do. This is not a grand collection of textiles, or couture, but instead she has a people’s museum of sewing and sewing tools. Amongst her collection she has an extensive history of how Singer Centres worked:

Nina: And there they would sell materials. They would sell notions, embellishments, buttons, everything on those Singer Centres and the sewing machines, of course. And there they used to give the classes too. Inside the Singer Centre, there were classrooms for embroidery and for sewing. Sewing used to be for clothes and for home decoration. You could have a, a degree study, an opportunity of learning how to sew, but not for people, but sew carpets, because they had all kind of tools for making the carpets, to make curtains, cushions, embellishments for the cushions, pillows, everything. Upholstery, they would teach this all how to change your chair or your armchair, the dressing, because this is all fabric. A house is dressed with fabric, right? Chairs have fabrics. So you have this three main courses: sewing for children and women, sewing for home decoration and embroidering.

JA: And, best of all, if you signed up for a course of classes you could take your own Singer Sewing Machine home right there and then without paying a cent.

Nina: They would first provide the person with a sewing machine that she could take home without paying. In exchange of making the class, she would get a package of 25 lessons, she would choose embroidery classes, what I told you, sewing for people, sewing for the home. She’ll choose on into that. She’ll get skilled, take her sewing machine home, and start working, getting customers. This was under a contract. And then, the Singer collector, the money collector would knock at her door on the established date, and she would pay on instalment. It was like an instalment plan. Singer was the first company to establish the instalment plan. First company in the world to have its system established was Singer.

JA: So Instalment plans were invented by Singer to help women invest in the capital cost of a sewing machine. In Brazil and other Latin American countries in the early 20th century Nina has no doubt that this was liberating:

Nina: This is the heart. The seed of the women’s financial independence was sewing, that like was the first step of being financially independent because women would have a lot of children. So, it was hard to be in the market, before birth control methods. But anyway, being pregnant all the time, so hard to, to want to be working out outside of the house was something very difficult. So, the sewing machine allow women to work at home.

JA: Nina’s collection focuses on the lives of poorer and middle-class women, she has wonderful manuals not just from Brazil, but from around the world, of the courses Singer and other sewing schools taught, and she is clear about what those skills brought the women who went on them:

Nina: Power, money, survival, independence. Because many women we don’t think about this. They would have lots of children and would be widowed. Okay. Men would die in wars. Okay. tuberculosis. So, women were left alone out in the rain with eight, 10 children to, to grow up, to feed. And where they would find this source of, of financial power? Sitting down at the sewing machine.

JA: Nina knows this was often poorly paid work but she also says that in a different time, for many women the sewing machine was their only hope. And she adds that because of the widespread skills that women grew to have in the first half of the 20th century, a whole economy and expectation grew up around elaborate and exquisitely executed clothing.

Nina: Absolutely. Absolutely. And then when you get a piece of a simple clothes, I’m not talking about those very embellished dresses as we see on museums. No, but, like a, a baptism piece of clothes, A regular one, medium class. There was many different types of embellishment applied to it. And it would be made by different people. So different women would make different works on a single piece of clothes. One would embroider, the other one would apply the lace. Just apply the lace. Maybe another one just making the pattern and the other cutting the patterns. I mean, you would have big, big shops with lots of women working. And there was the owner, probably a woman or maybe even a man, who owned that shop and had like, sometimes hundreds of women working in that certain shop, specialised on a certain kind of clothes, type of clothes, baby clothes, baby, christening gowns. It’s not baptism in English. We say christening gowns. They were very fashion bridal clothes, like wedding dresses. They were all on specialised people would make wedding dresses.

JA: This is exactly the kind of overlooked history that Nina has in abundance in her collection which she started over 20 years ago.

Nina: In the beginning of the year, 2000, I understood that this skill was being wiped out. People will go into fashion schools and they didn’t know, and they not interested on learning how to sew. They would understand that sewing was a minor career. They want big careers, they want the catwalks, they want to be on the great fashion show. They all want to be Karl Lagerfeld. But they didn’t care about learning how to sew. So, I spotted, I noticed that this knowledge would fast was disappearing, already, 2007 already I saw that people sometimes will complain, oh, I don’t find a seamstress to do some a certain piece. Oh, there is no seamstress. No, there is no seamstress because nobody cares about training new seamstresses. So I collecting old books old methods of sewing and notebooks on sewing and like students notebooks from classrooms. I was very much dedicated on doing so collecting in Brazil, collecting on eBay, collecting in Argentina, because I have a picture now that this kind of school used to exist all over the world. So, I started collecting these books on the how to sew, how to correctly take measures. How do you make a pattern, how do you do the finishings? I would say these are the grammar, grammar books on sewing.

JA: Her collection now fills her apartment and another one close by. Anyone who is interested can visit to see some of the extraordinary sewing tools, samplers, manuals and magazines she has from all over the world. She says that from the collection she can pinpoint the moment that sewing skills started to decline:

Nina: By the end of the seventies, is when they start declining. We see the declining on the publishings, the magazines. Women wouldn’t buy anymore a magazine to do some knitting or to do some crochet, crochets kind of coming back a little. But they start dying on the seventies with the hippie movement, the birth control pill. Yeah. people start going out of the house to work. The economy in general required women to go out and work. The economy didn’t allow anymore just a man to support a house full of kids. They need both to support less kids So, this all started on the end of the seventies when women, they wanna go to university, they wanna become doctors, engineers. They, they wanted to have other careers than careers in like a home related career.

JA: And then as these women died, their relatives threw out the old sewing and flower making manuals, the dress making and knitting magazines. Only Nina saw value in them:

Nina: I think, oh my God, I gotta save this. I gotta find a place, which is my main concern nowadays, to make a donation, to give a destiny for this collection. Because nowadays, now people don’t care about, like those young women. They not interested. It’s different than when in the past that when they understand this as a career. And nowadays I look a place where I could donate my, my collection, because this was something that worried me very much during Covid, that if I die, my daughter, she doesn’t like any of this. And if I die, this all go to the trash the next day.

JA: Nina believes it’s important to save her collection:

Nina:I want to know that this is preserved. Because I know my collection is important. It’s humble. I don’t have any government support. And, and I don’t look for, I’m not rich either. I wanna keep my collection. That’s all that matters to me. But I wanna donate this. Like if one day I could get a hold of someone on the Victoria and Albert and they want my collection, it’s all theirs, because this gotta be saved. I have over 150 of those samplers albums plus sample fabric, I have crochet, I have lace, I have sewing, I have darning, I have flower making. And this gotta be kept preserved somewhere. I’m doing my part, while I’m alive. But we don’t last forever.

JA: Nina’s point is that if the samplers and the sewing tools, the magazine and the books of instructions are lost, then we will lose part of ourselves and our history – and without it we will never fully understand the beauty of what we see in the grand museums of dress and fashion, or how clothing is constructed or what cloth and fabric can be made to do:

Nina: And this is what’s important for me in my collection, is to save this knowledge, because this is something important that I would like to tell you, is that we see many fashion museums in the world. I’ve been to many, I’ve been to the Victoria and Albert, I’ve been to Bath where there is the fashion museum in Bath in England. I went to FIT, I lived in Washington. There was this Smithsonian, all of them. They have beautiful collections, period. In Portugal the Museum of Traje, Build, Barcelona. But no, no museum that I know of keeps the how to make those pieces. They don’t have the methods. I do have the methods.

JA: But for me it’s not just the methods and know how – which is important – it also the understanding of how the sewing machine opened new doors for millions of women and allowed them to make their own living. It’s a universal tale that unites women, and some men. Sewing is a fundamental human activity that connects us directly with our own past and has something important to tell us about who we are and why we stitch today. And yet it is a story that has been almost completely overlooked. There is almost no research on what women felt about this, how these skills did actually change their lives or how it helped the economic circumstances, not just of their families but of their countries too. And if it wasn’t for the chance survival of archives like Whitelands, with its immaculate plain stitch samplers, or for the passion and care of Nina Sagaço, these lives would have been erased and lost to us forever.

These are slender threads on which the experiences of so many women around the world rest. There is a lot more to be discovered and said, and next month we will hear from someone who has much more to add to the story of why sewing is important. Until then I want to thank Nina Sagaço for her ability to see the value in something others tried to throw away and Vivienne Richmond for her research into the lives of the young teachers at Whitelands. I also want to thank Louise Kerr – voice coach extraordinaire – for her excellent reading of Kate Stanley’s book.

If you find yourself in Sao Paulo, Brazil, contact Nina and go and see her collection. She welcomes visitors. You will not be disappointed. The details, along with pictures, are on the page for this podcast at www.hapticandhue.com/listen. It is episode number 44, series 5.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews, and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast independent, and free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you extra content every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted by Bill Taylor and me.

Meanwhile we’ll be back on the first Thursday of next month with news of Haptic & Hue’s book of the year. Join us then for another episode and until then enjoy your making and thank you for listening.