Whole Cloth From The Hills

North Country Quilts

Episode #21

North Country whole cloth quilts are very different from patchwork quilts. Their showmanship lies in the swirling design of the quilting stitches on a completely plain background. Quilting is a technique that goes back centuries, used by rich and poor alike to keep warm, as a rudimentary armour in battle, and to dress babies. The episode explores how it became identified with an area of England that stretches from North Yorkshire up onto the Scottish Borders and developed an elaborate artistry all of its own – one that even today is little known and appreciated.

This episode runs for 37 minutes.

A very big thank you is due to Deborah McGuire for her help with this episode – her skill with the needle is only equalled by her wonderful store of stories about quilting of all kinds. You can find her website at https://plainstitch.co.uk/and you can find her on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/plainstitchdeb/

Thanks are also due to Heather Audin, Curator of the Quilters’ Guild Museum Collection in the UK. You can find the Quilters Guild Collection at https://www.quiltersguild.org.uk/about/the-quilters-guild-collection. You can find Heather on Instagram @audinheather, and the Quilters Guild @thequiltersguild.

Thanks also to Frances Wood – friend, Haptic and Hue listener, and Northumbrian Piper and Pipemaker – for his rendition of “Because He Was A Bonny Lad”, a traditional Northumbrian tune. You can find out more about Northumbrian Pipes at https://www.northumbrianpipers.org.uk/

The Bowes Museum can be found at https://www.thebowesmuseum.org.uk/ It has a current exhibition of some of its collection of whole cloth quilts, which ends on January 9th 2022. It has a good virtual display of the exhibition – which you can find at https://www.thebowesmuseum.org.uk/Exhibitions/2021/North-Country-Quilts-In-Celebration-of-New-Acquisitions. At the bottom of the same page, you can find two good books on these quilts, both by Dorothy Osler: one is called North Country Quilts: Legend and Living Tradition, and the other is called North Country Quilts: In Celebration of New Acquisitions, which is the catalogue for this exhibition.

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Deborah McGuire, Quilter and Quilt Story Teller

Deborah at Her Quilting Frame

Deborah Quilting Outdoors at Frame

Traditional Quilting Frame

The Quilters Tools

Heather Audin, Curator, Quilters Guild Collection

The Original Misses Barron Quilt made in Allendale 1900-1925

Quilted at The Bowes Museum in 2000, mainly by Evelyn Jones and Elsie Gibson

Detail of Quilting by Elsie Gibson and Evelyn Jones

Deborah’s Quilt made in Tribute to the Misses Barron Quilt

Deborah’s Quilt at The Great Northern Stronghold, Bamburgh Castle

Detail of Whole Cloth Quilt, from The Bowes Museum.

Whole Cloth From the Hills

Script

Most of the textiles in this series are great travellers. For millennia cloth has been an efficient migrant, wandering the world by sea and land to tantalise and interest human beings ever in search of the new, the different, the colourful and the beautiful.

But every now and again we come across a cloth that doesn’t do that, instead, it settles in one place and puts down strong roots, becoming part of that region’s identity and culture. People develop great pride in it and see it as part of their heritage. This episode is about one of those textiles.

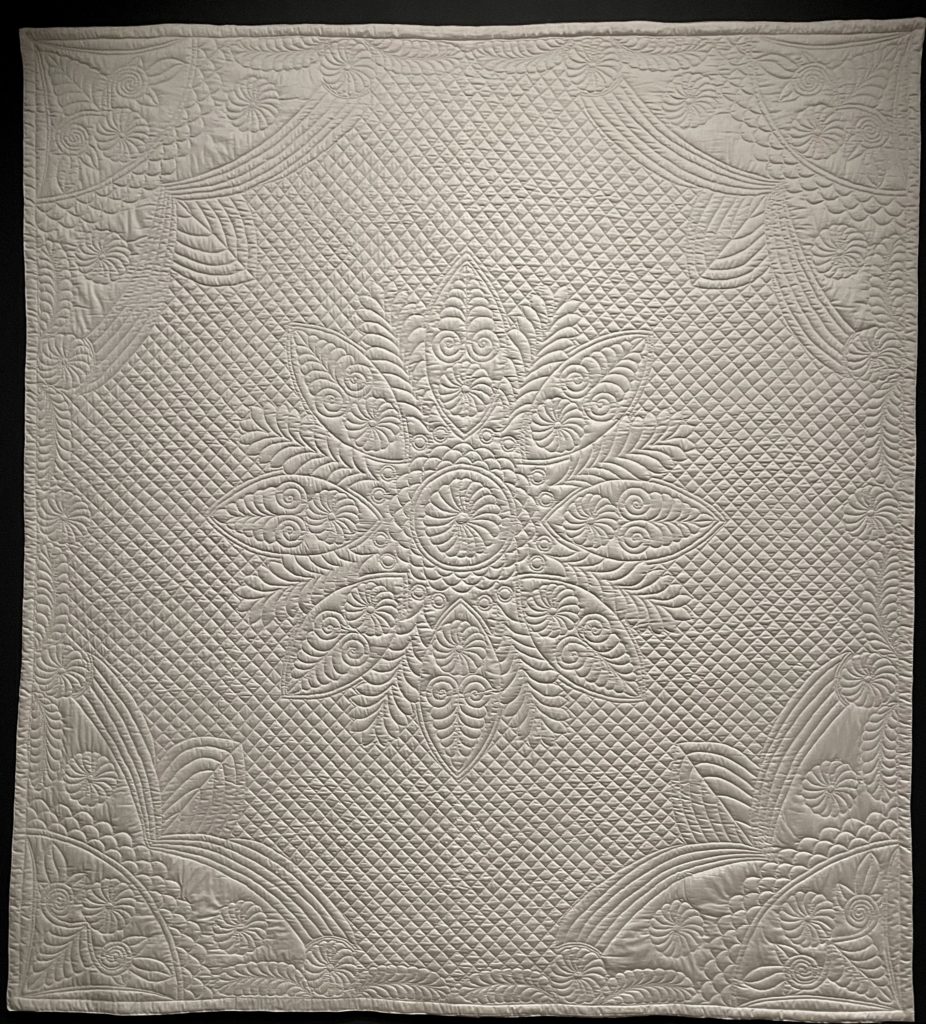

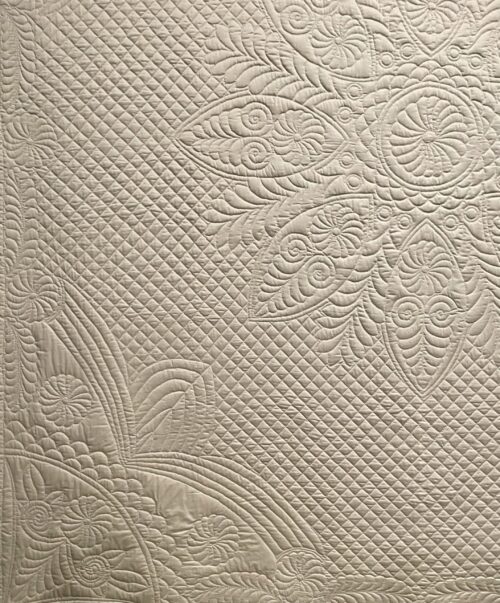

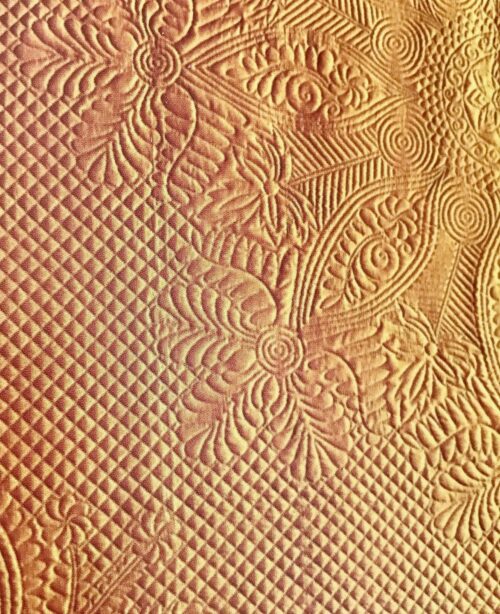

So the quilt that I have chosen to talk about today is a beautiful ivory coloured sateen, whole piece quilt. So this is a single piece of fabric with a slight sheen to it, a cotton fabric, and it has been quilted all over quite tightly, so close together to make a sort of undulating pattern. And it’s been quilted in such a way that there is a large kind of round or pattern in the middle which almost looks like a flower full of sinuous curves and swells and flowers that then sits in the centre of the quilt. And then around the outside is a large swagged border. So more floral motifs large swags of feathers and swells and scallop shows. So this is something of great beauty, very glamorous but also very subtle. It is, is made of a single piece of white or cream fabric. All of the pattern, all of the interest comes from the texture that is created by the quilting stitch and the quilting. Stitch is just a running stitch. There is nothing clever or complicated about creating the quilting, stitch it, it just allows you to create, these are areas of light and shade, which then in the correct light produces a quilt of, of great kind of glamour and complexity.

Deborah McGuire is a researcher and an incredibly skilled stitcher of whole cloth quilts and this is the third series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles, which is called The Chatter of Cloth. My name is Jo Andrews and I am a handweaver interested in how textiles speak to us and the impact they have on our lives. In each episode, we start with a different textile and unravel its story. This time we begin with a cloth that has become associated with a deeply rural area of northern England, a district that spreads from North Yorkshire up to the Scottish borders – which is sometimes known by quilters as the North Country Quilting Counties. These are not wealthy areas, in fact, quite the opposite. Most of the landscape is rugged moorland that bears the scars of Britain’s early adoption of the industrial revolution. The quilts that were made here have an integrity and a strength of purpose which reflects this countryside in which they were made. But before we go on any further we need to establish that whole cloth quilts are something quite other from patchwork:

This is a fundamental difference that often gets sort of smoothed over in modern parlance. So we tend to say patchwork and quilting almost as if it’s a kind of compound word, but patchwork and quilting are two very different things. And they have their own rich histories that stretch back into the past. Our whole cloth is a, a quilt made of just a single piece of fabric on the top and a single piece of fabric on the bottom. And some sort of fluff in between, whereas patchwork is people will probably be more familiar with is taking lots of little pieces of fabric and putting those together in a style that then creates a pattern on the top. Patchwork is often also quilted. It is sewn to a wadding and a backing in order to make a sort of fluffy three-dimensional quilt, but obviously, all of those teams stand in the way of really dramatic quilting. It’s quite hard to execute that kind of rocking stitch of quilting stage over lots of scenes. And, and that’s the reason I think, why a lot of people no longer use a whole cloth or no longer use hand quilting as a method to finish their quilts because it has become so intertwined with patchwork. And that is a more difficult way to sort of access the skills of quilting. Whereas in the past it was a separate sort of method of creating fabrics that really wasn’t very often connected with Patchwork, the two things only really came together at the beginning of the 19th century when people could access lots of cotton fabric.

Whole cloth quilting – where the stitches are the star and not the pattern made by the fabric, requires a different approach. First of all, you need a quilting frame, something that looks a bit like a wooden single bed frame, the quilt is lashed to that and then the quilter uses a specific stitching method to create the pattern.

And anybody who is a hand quilter will know that the method of hand quilting is something that’s very kind of rhythmic. It’s a muscle memory that is a sort of rhythm. The needle is, is held and rocked in a sort of method that is very unique and is you know, hard to learn, but not complicated. If you see what I mean, it’s a kind of technique that rewards perseverance.

Heather Audin is the Curator of The Quilters’ Guild Museum Collection in Britain. There are more than 900 pieces in the collection. She is interested particularly in the social history of costume and textiles and says that whole cloth quilts have a very different appeal to patchwork.

Sometimes they’re a bit niche. So people don’t always take to them if they are very into printed fabrics or they’re into patchwork designs. But actually, I think once you start to look very carefully at whole cloth quilts and you realize all the hand quilted detail and the skill of the draftsmanship and creating these beautiful patterns you realize just how amazing they are and how skills the people are that must have been making them. So they do have a very different appeal to patchwork. And I think, you know, sometimes people find them hard to get into, but they, they have beautiful designs beautiful and motifs. And once you realize that the whole design that you’re seeing, when you look at a whole cloth, the quilt is just purely created from running stitches, which have gone through the three layers. There’s no cutting up. There’s no adding bits on, there’s no embroidery embellishment, all the design and the beauty of the textured relief that you’re seeing is just created by a running stitch and very well designed and thought out running stitch, I think you gain like a, an extra level of appreciation for what whole cloth quilts really are.

Quilting itself is an old and venerable craft, one that sits much more within what we think of as the tradition of embroidery, as Deborah explains:

The history of quilting goes back before history. So, you know textiles are fragile and they decay. So we have to look beyond the existence into examples of quotes in literature that reference quilts. The terminology was very rich. The spelling was very rich. So you’re often looking for, we kind of interesting ways that a quilt can be spelled with a C w or, you know, all sorts of different sort of ways. And they also had lots of different words that described quilts. They were called coverlets or coverlets. They were often you know, refer to in lots of different ways, but we know that quilts existed. So some of the earliest references to quilts describe whole cloth quilts. So we can go back into the sort of 1590s. So Edmund Spencer wrote the lyrical poem, epic poem the Faerie Queen, he wrote that poem for Queen Elizabeth the First and in that poem, he references a quilt and he describes this quote as being light purple silk woven upon with silver quilted upon satin, milky white. I mean, that’s a very glamorous quilt that all of us aspire to sleep under. And we know through the Tudor period these very sort of glamorous sounding, very expensive quilts were part of the normal inventory of elite houses. We know that Henry the Eighth had a vast number of quilts in his inventory. They are mentioned in the inventories when he passes on quilts to his many wives. Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester has a particular kind of evocative description of a quilt in one of the inventories of his house or another castle in the inventory. It describes this quilt as being a fair quilt of crimson satin, all lozenged over with silver twist in the midst of cinque trefoil with a garland of fracket staves, fringed about with crimson, lined through with white fustian.

I’ll definitely have one of those! And here we have one of the problems with the past – it’s the records of the rich that tend to get preserved not those of the poor, but Deborah says it wasn’t just the high end of society that had quilted clothing.

So certainly, for warmth also for protection. So we know in descriptions of armour and armaments, that people wore quilted Jerkins underneath the heavy metal armour, and that would protect the body and also give heat. And that tradition continues. So if we follow the kind of silken thread of quilting through the decades when we get to the 18th century, we know that quilted clothing was very popular. It was the height of fashion. Women wore quilted petticoats and open-fronted gowns. Men wore quilted caps in bed, when they took off their large powdered wigs, their shaved heads would be cold, so they would wear these little kind of quilted caps. Certainly, babies, elite babies, would wear these quilted layettes where they would have effectively like a mummy and me kind of connection. So they would create these little quilted jerkins for the baby. And then the mother would have a similar waistcoat or jumps, so a sort of loose form of corsetry that women could wear when they were breastfeeding a child, those were very often quilted as well.

Quilting was a professional trade. And then as the eighteenth century progressed things begun to change. Cotton cloth, much of it wonderfully patterned, began to arrive across Europe and later America, from India. By 1800 it had become widespread and affordable and It brought about a revolution in what people wore and bought.

The history of quilting runs through the centuries independently of patchwork. And then the two of them come together at a point where cotton fabrics became more available. And that’s really where people tend to kind of root their understanding of this. They think about patchwork quilts and patchwork quilts were a huge fashion at the beginning of the Victorian age when these fabrics became available and they, often were also quilted. So the waters become a little more muddied in the Victorian age. And it’s only in certain places where the whole cloth quilt retains its sort of power.

Heather Audin makes the good point that at this stage the two quilting traditions – patchwork and whole cloth were practiced by different kinds of people.

And traditionally patchwork has always been seen certainly in the 18th and early 19th centuries as an upper-class pursuit. So, the ladies would sit there and do their patchwork in the evening and it would be very much something that ladies of leisure would do to kind of take up time, but also to create beautiful and decorative things from very expensive fabrics that they had at home. And certainly, in the 18th century, the two crafts were all always considered quite separate. So you would get patchwork and you’d get quilting, but you wouldn’t necessarily get them together. And certainly, the ladies who did the patchwork would not then quilt those pieces. So, you get very beautiful 18th-century quilted pieces, but they’re often made in a professional workshop rather than a lady doing that. So, you have quite a separation of the crafts, which I guess kind of polarizes it slightly into considering something kind of higher status or lower status.

Middle-Class Victorian society came to look down on quilting – this was something that people more commonly might have done for money – not as the decorative leisure activity that was patchwork. So, it was in the poorer rural areas, Devon and Cornwall, the Welsh Valleys, and above all rural northern England where quilting survived later into the century.

In order to understand why people were still making whole cloth quilts in these places, you really have to go inside their homes. So what was it about living in a farm in the Durham Dales or in the Yorkshire Dales or in Cumbria or Northumberland that meant that you were still making quilts that looked like this, because obviously at first glance, there’s a slight dichotomy there isn’t there? These were places where rural poverty was significant, people were farmers, they were lead smelters, they were miners, they were doing jobs that were not, the sorts of jobs that meant that you were living in a pristine home where this beautiful kind of silken item would be part of your fashionable display, but the quilt became something different. It became an element of regional identity. It became about I’m from this place, I’m from this family or even this valley, because the patterns that were being used what always, so at the beginning of the 19th century, they were always based on what was around people. So we see lots of whole cloth quilts down in Devon and Cornwall with sort of beautiful flowing floral motifs in Wales, you see some of the kind of Celtic influenced shapes and swells, sort of patterns. For these people, quilting was not a discipline that existed outside of people’s everyday lives. You see the same kinds of patterns on things like coughed, butter pats, as you see on quilts on carved stonework and woodwork, these were effectively patterns that were being taken from everyday life.

Deborah McGuire believes that these whole cloth quilts, tell us a good deal about ordinary people’s lives, their culture, and their identity:

I feel like the whole cloth quilt is very much under-appreciated, you know, for its power of telling working-class histories, because I think we tend to look at whole cloth quilts and we think of it as being something very kind of sumptuous and about neat interiors and very much a kind of domesticity there, that we’re not quite so comfortable with today, but actually, these were items of hope weren’t they? When you were living a precarious life when you were working incredibly hard every day in order to kind of keep food on the table these items were items of loud, aesthetic ambition. It tells us about how people dream, about how people value beauty in all circumstances. The economic history of whole cloth when it moves into our century is still about poverty, but it’s not about poverty in making quilts from scraps point of view. It’s about facing poverty square in the eye and making the best of it.

These quilts were created as part and parcel of people’s lives, and as an expression of their enduring relationship with fabric. These people lived in a time of immense change, they had one foot in the rural past, and the other in an industrial future. One way in which they dealt with these changes was through an assertion of identity in the patterns they created on very simple cloth, It was something that belonged to them and which they had control over, reminding me very much of the belief that things make us as much as we make them.

They were not necessarily something that you talked about separate to your everyday life. And so they pass under the kind of radar of history in the same way that we don’t talk about how we’d clean the floor, or how we did some weeding, they were a part of people’s everyday lives and therefore they were in plain sight, but not commented upon. And that’s part of the challenge today is in re-igniting or repopulating the stories, thinking about that kitchen in a north country farm, you know, with its large blacked range, the cast iron ranges were also cast with beautiful patterns. Some of those patterns are the same as patterns that we see in quilts. In busy houses quilt frames were on the same kind of dolly maid, you would dry your laundry on, that could be taken on a pulley, up to the ceiling. So, they could be moved out of the way when normal life went on around it. These women were quilting by candlelight, by reed light, who knows. It’s when we actually place the quilt in the context of the home, it was made by the people who stitched it, but also the people who slept underneath it.

And it’s the contrast between the quilts and the difficult hard toil of a subsistence life that Deborah finds interesting: this very human trait of seeking something beautiful even though you might be surrounded by poverty and industry. These North Country quilts have the ability to help make houses into homes, give comfort and provide pleasure for the eyes and solace for the hands.

But you see, I think when we’re thinking about that, the reason that this is so important that it gives us this context of how it was made is to think about these shimmering whole cloth quilts in that environment. So they’re killing the swine, they’re salting the pig and the women are working on this beautiful artistic whole cloth, shimmering white, satin quilts. the juxtaposition is so interesting. This was not really about the idea of a fashionable home. It was much more tied up in the idea of having a home that was representative of your efforts and your work, it was about people taking pride in their living conditions and also their identity being tied up in the idea of hard work, graft. A whole cloth quilt was something that very perfectly matched that, it measured out the extent of your labour. Every one of those stitches is there for people to see it was about I have made an effort in order to make an item of beauty that enhances my workaday life, and that’s where that magic is.

That’s the sound of the Northumbrian pipes, which like whole cloth quilts are part of the community traditions of this part of the country. People came together to play the pipes just as local women came together to work on Wholecloth Quilts – not in quilting bees as in America, but in what was called Twiltings:

But certainly, in the North country, people did come together and work together on quilts. It was more likely to be kind of family groups. So it was a part of everyday socializing. It was about how you visited your parents after church on a Sunday, and you worked on the quilting together. So with the twilting, that was the sort of vernacular way of describing quilting. And that again has its roots in a kind of old English, quilts were described in lots of different ways with TW’S, and with CW’S. So the twilting that is, is being done here is just part of, kind of socializing visiting. It’s also about a shared economy.

And in time as skills were honed people realised that there was also a commercial opportunity here, there were professional quilters who would make your Wholecloth quilt if you had the funds to pay them, and then there were the quilt stampers, the people who made a business out of tracing the design onto your cloth so that you could follow the lines and stitch these astonishingly complex patterns for yourself.

So, by the 1880s, we start to see what were known as quilt stampers. So, these were people who the most famous of which is a gentleman called George Gardiner. And he was a Draper in a village in Allendale. And he, I guess, had an economic opportunity to reinstate a skill or a trade that would have been there a hundred years before where he would mock out the pattern for you. But certainly, these quilt stampers in the North East had a thriving business. So, we know from some of their records that they took on apprentices a particularly famous apprentices for George Gardner. It was a woman called Elizabeth Sanderson. And she went on to create quilts of her own style, which became very popular. And you still see vast numbers of these quilts. And they were very much influential on what we now consider to be the kind of North East style of whole cloth.

But by the 20th century, the practice of making whole cloth quilts was dying out, people were beginning to lead different lives. They were briefly revived in the 1930s as part of a government-backed scheme to help mining communities earn some income in the Depression, but then they seemed to disappear again. Heather Audin, Curator of the Quilters Guild Collection, says everything goes up and down in popularity:

So, we’ve had times in the past where whole cloth quilting has been very popular and then it’s perhaps declined again, as skills are not passed on to the next generation or people just start to prefer other things and fashion and society changes. So whole cloth quilts are sometimes seen as a little bit old-fashioned, something that your grandma might’ve had, and we want something a little bit different. I suppose some people see it as only being able to produce a certain type of look. So there are perhaps more options when creating patchwork pieces because you can do a patchwork quilt in two different colours and fabrics and prints and designs. You can paint fabric. Now you can do different dyeing techniques. So perhaps there’s maybe a wider appeal for things which have a little bit more variation to them and whole cloths tend to be quite traditional in their look.

The Guild began collecting quilts in 1979 and Heather says that 2 whole cloth quilts were among the very first items they were given.

So they were donated in 1980 and we call them our collaborators quilts. So they were from quite an important period in whole cloth quilts in history because in the early 20th century, there was a real fear that the skills of whole cloth quilting were going to die out and not being passed on to the next generation. So as part of the Royal industries bureau, which was trying to revive a lot of traditional crafts, which were dying they had a whole scheme whereby they would get quilters to teach the next generation, but also produce commissions. And these commissions went to very high-class clients, such as London hotels, like Claridges, and they would employ women to create these pieces, which would then go in very fancy hotels. So these two Claridges quilts were created in the 1930s as part of the Claridges’ newly refurbished art deco wing.

Heather also says that the tradition of whole cloth quilting is being updated and re-worked by modern quilters:

So we’ve got a couple in our collection, which are very much rooted in that traditional style of whole cloth quilting but are very, very modern. So we have two pieces in the collection by an artist called Michelle Walker. But she’s kind of changed the traditional design and also the materials that she’s using as well to reflect some environmental and political statements that she’s trying to say. So, one of them is called field force and it’s a huge whole cloth quilted piece done on a sewing machine. But the quilting pan instead of being traditional motifs is actually tire-tread patterns. And the top layer of the quilts is actually pieced together from household plastic bags. So, it has a very environmental statement to make. And it’s about the churning up of the countryside and the tire tracks that kind of forging their way through the countryside. And obviously, the plastic bag has that environmental feeling too. And then another one in the collection and also by her, it’s a very similar feel to it. And it uses a rubberized coated cut and lining material. So, they’re not traditional materials in any way, but, the three layers and the stitching through the three layers and creating the whole cloth pattern is the same as it was traditionally.

The Bowes Museum in County Durham is one of this region’s great treasure houses of formal European art and painting. In the early 1960s in what was then an astonishing departure, the Bowes started collecting whole cloth quilts. It now has one of the best holdings in the world of these lovely quilts, which have seen so much life and given such pleasure to the makers and the receivers down the generations. Its current exhibition of North Country Quilts ends in January 2022. At one stage the Bowes Museum thought that all the significant whole cloth quilts might have been located – that is until the Quilters Guild set out to locate family quilts. The textile curator at the Bowes, Joanna Hashagen, was astonished by the result as Deborah McGuire explains:

The Quilters Guild ran a, effectively like Antiques Road Show. So, a heritage project where they went from town to town around the UK at the beginning of the nineties. asking people, locally, advertising in newspapers to bring in family quilts. And one of the locations for that was The Bowes Museum. And they had thousands in that period, and I think Joanna admits at that point that she realized that, these are items that have as much significance in the emotional lives of the people that own them as they do in the kind of social and historical story of our country and our regions. And I think we’re finally recognizing that and work like the exhibitions that were put on in the North East of England at The Bowes Museum which came about from the work of the quilt historian, Dorothy Ostler, have done huge amounts to cement their importance in British quilting history, yet still many people don’t know a lot about these histories.

Which brings us back to the quilt that Deborah chose to start this episode. It has a very special history as it represents a stepping stone between the quilters of the past and today’s quilters. It isn’t an old quilt, it was made just over 20 years ago by two women who worked on it in public at The Bowes Museum as part of a landmark exhibition there:

Evelyn Jones and Elsie Gibson in the year 2000, when they made this quilt, they were older ladies. They had trained in the 1930s in the skill of quilting. And that came about due to a scheme an economic scheme called the Rural Industries Bureau. And this was a way between the wars of economically stimulating the regions. So, these workshops were set up in places where quilting was still traditional, where people still had those skills. And these two ladies worked in that workshop in 1930. So, they were trained by women who themselves were elderly at that time who had been working in this vernacular tradition in the Victorian times. So, they are effectively a link in the chain of the passing on of the scale, the practice of making these quilts. Amazingly the information about the exhibition talks about how they hadn’t done any quilting for maybe, you know, 60 years in between, but they fell straight back into this. And so that makes complete sense to me that they would be able to fall straight back into creating these little stitches. So, the fact that these women were able to bring that back, they introduced a whole new generation of quilters at that time.

The quilt they made 20 years ago was a new version of a classic north country whole cloth quilt. There is another variety of this design in the Bowes Museum which was by two sisters in Allendale both called Miss Barron, in the early 20th century. The final stepping stone in this series is represented by a modern quilt inspired by the work of the Barron sisters but interpreted in a different way to celebrate the shapes of the unique patterns of these quilts, which was made by Deborah herself in tribute to the quilters who have gone before her.

And so, you know, this was about resourcefulness. It was about you know, people making beauty out of what they had, but in ways that weren’t about lack, they were about bounty, you know, creative, bounty, luxury beauty. And I think in that is the story, the vernacular story of the North East. You know, it’s a very powerful story today in a world where, you know, we talk about levelling up and regional identity. But that we’re so aware that we’re in a global economy. The stories of patchwork and of quilting are global stories, the sorts of stories that you tell all the time on your beautiful podcast about, you know, flows of labour, about fabrics moving around the globe, but essentially this is about people living in a locality and relying on their neighbours and making things that reflected their own individual identity. And you know, that’s, that’s a really powerful story today as it was in the past.

Thanks to Deborah McGuire and Heather Audin of the Quilter Guild. If you would like to find out more about them or about these quilts, then you can find resources and links at www.HapticandHue.com/series-three

Thanks too to Francis Wood for his rendition on the Northumbrian Pipes of the tune Because He Was a Bonny Lad, and to Bill Taylor of The Lark Rise Partnership who edited and produced this episode, and lastly to all those listeners who helped to make this third series possible by supporting it via the Buy Me a Coffee button on our website.

Next time we will be on the trail of a cloth that is having a real moment in fashion at the moment. African wax cloth, or Ankara cloth, is supremely associated with Ghana, Nigeria, and Togo where it has become woven into a rich cultural heritage. But its story is not what you would think – it’s a curious one of chance and a long voyage across the face of the globe. Join me next time to hear more.

I wanted to leave you with a poem about the beauty of north country whole cloth quilts and a sense of the women and men who made them. But it is part of the vast literary gap that there are, of course, none. No one thought these lives or this activity worth committing to poetry that I know of. But the landscape of this area is remembered. There are a number of poets who loved the wild open moors dotted with old industrial workings. One of them was WH Auden. He spent enough time here for the landscape and the place names to enter his soul. In 1940, as the world was engulfed in fear and war, he was in America, but this was the place that called to him as he wrote his long poem called A New Year’s Letter. Here’s are some verses from it.

Whenever I begin to think

About the human creature we

Must nurse to sense and decency,

An English area comes to mind,

I see the native of my kind

As a locality I love.

The limestone moors that stretch from Brough

To Hexham and the Roman Wall,

There is my symbol of us all,

There, where the Eden leisures through

Its sandstone valley, is my view

Of green and civil life that dwells

Below a cliff of savage fells.

Always my boy of wish returns

To those peat stained deserted burns

That feed the Wear and Tyne and Tees

And, turning states to strata sees

How basalt long oppressed broke out

In wild revolt at Cauldron Snout.

For all in man that mourns and seeks,

For all of his renounced techniques

Their tramways overgrown with grass

For lost belief, for all Alas

The derelict lead smelting mill

Flued to its chimney up the hill

That smokes no answer any more

But points, a landmark on Bolts Lane

The finger of all question.