Paisley – The Pattern Nomad

Episode #20

Paisley has many names and even more meanings. It is the sleeping dragon of patterns – retiring under the hill for decades of slumber before being re-purposed by new cultures and new generations to signify something different. It belongs to many hands and no one in particular seems to be able to lay claim to it, making it one of the truly global patterns. Listen to the journey of this nomad in this episode of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles.

This episode runs for 36 minutes.

Grateful thanks to:

Lucy McConnell, Textile and Dress Historian from Paisley in Scotland. You can find her on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/diary_of_a_dress_historian/ or Linked In https://www.linkedin.com/in/lucy-mcconnell/?originalSubdomain=uk or on Twitter @Diary_DressHis

Mira Gupta, the Textile Historian who is on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/miragupta20thcentury/ She is also a wonderful contributor to the Facebook community called Ethnic Textiles Community.

Rachel Mansi – Collector of 1960s and 70s textiles, you can find her on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/rainbowvintagehome/

Further Resources:

There are a number of YouTube videos of weavers making Kani shawls which will give you some idea of the labour involved.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3obD_jNY7bE

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GV7rDEkUHBY

The town of Paisley has embarked on a project to embrace its history of producing the shawl and has transferred its entire collection to the rather wonderful looking Victorian Art Gallery in the town, out of the slightly musty library where it used to be held. The Gallery is undergoing a major refurbishment and is due to open in 2022, but it is firmly closed at present (Autumn 2021). Also in the town is one of the original weaver’s houses, Sma Shot Cottages, and also Robert Tannahill’s Cottage which was a four-loom weaving shop. both are currently closed (September 2021).

The modern Kashmiri weavers’ enterprise run by Jenny Housego and Asaf Ali can be found at https://kashmirloom.com/pages/about-us

There are many books on Paisley/Buteh/ Kairi:

Valerie Reilly who was Keeper of Textiles in Paisley wrote The Paisley Pattern: The Official Illustrated History. ISBN 9780862671938. It can be found new or second hand at https://www.bookfinder.com/search/?ac=sl&st=sl&ref=bf_s2_a1_t4_4&qi=IQlZABmok2zEM9Oxqoj6orUWyes_1497963026_1:75:175&bq=author%3Dvalerie%2520reilly%26title%3Dpaisley%2520pattern%2520the%2520official%2520illustrated%2520history

There is also The Paisley Shawl by Valerie Reilly: ISBN 0-86122-026-9

In the Haptic and Hue Bookshop is The Victorian Paisley Shawl by Chet Gadsby which is a review of shawls produced in different centres in the 19th Century you can find it at: https://uk.bookshop.org/a/8778/9780764315701

Lastly, there is Avalon Fothingham’s wonderful book The Indian Textile Sourcebook which you can find at https://uk.bookshop.org/a/8778/9780500480427

If you use the links to the last two books and buy from those, Haptic and Hue receives a small commission at no extra cost to you.

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Lucy McConnell and the Shawl she chose

Lucy’s Paisley Shawl

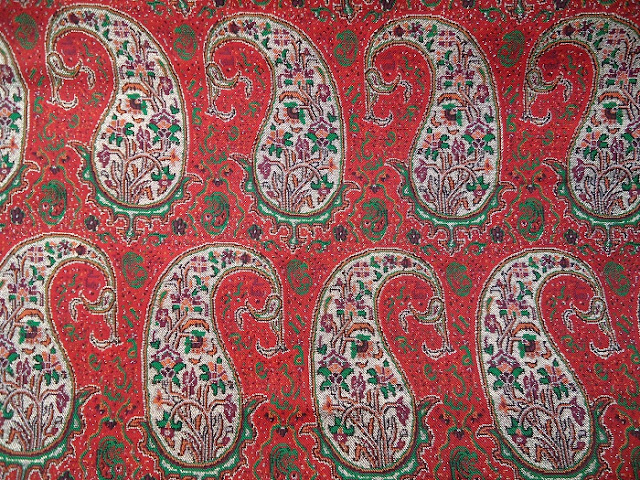

Woollen Paisley Shawls

Fanny Hunt by William Holman Hunt

Paisley Jewellery belonging to Queen Victoria

Captain John Foote, Joshua Reynolds

Mira Gupta, Textile Historian

Mughal nobleman in Paisley

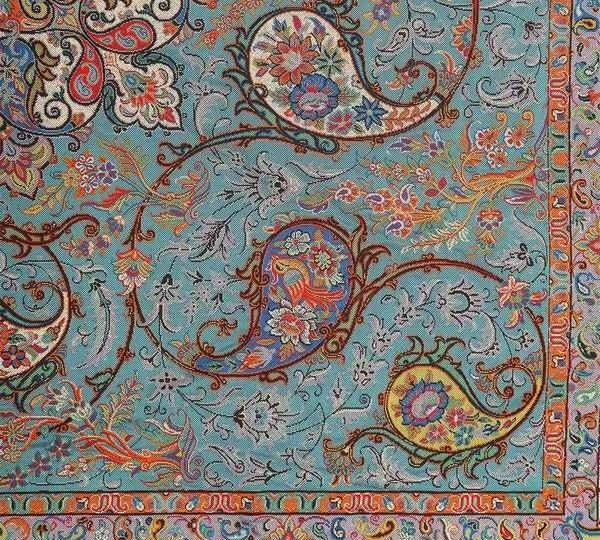

Kashmir Shawl

Kani Weaving

Pashmina Shawl

Paisley motif

Rachel Mansi

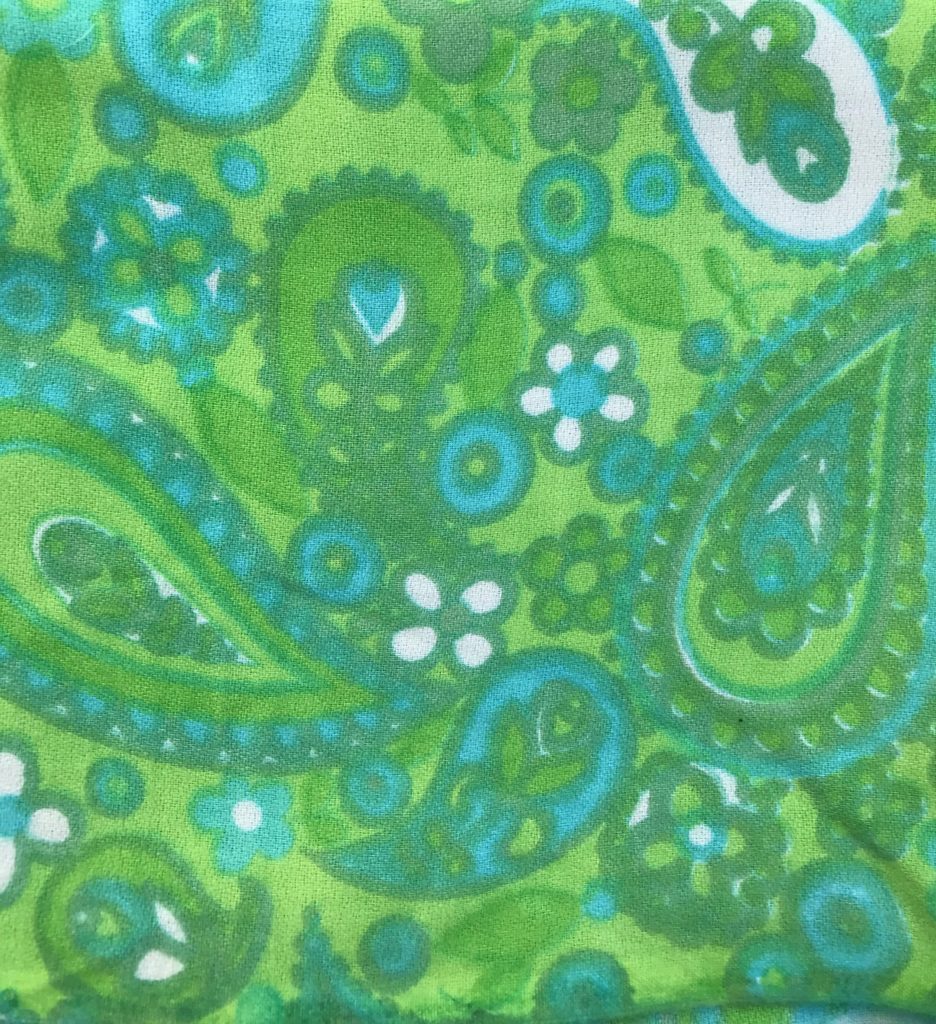

1960s Paisley Fabric UK

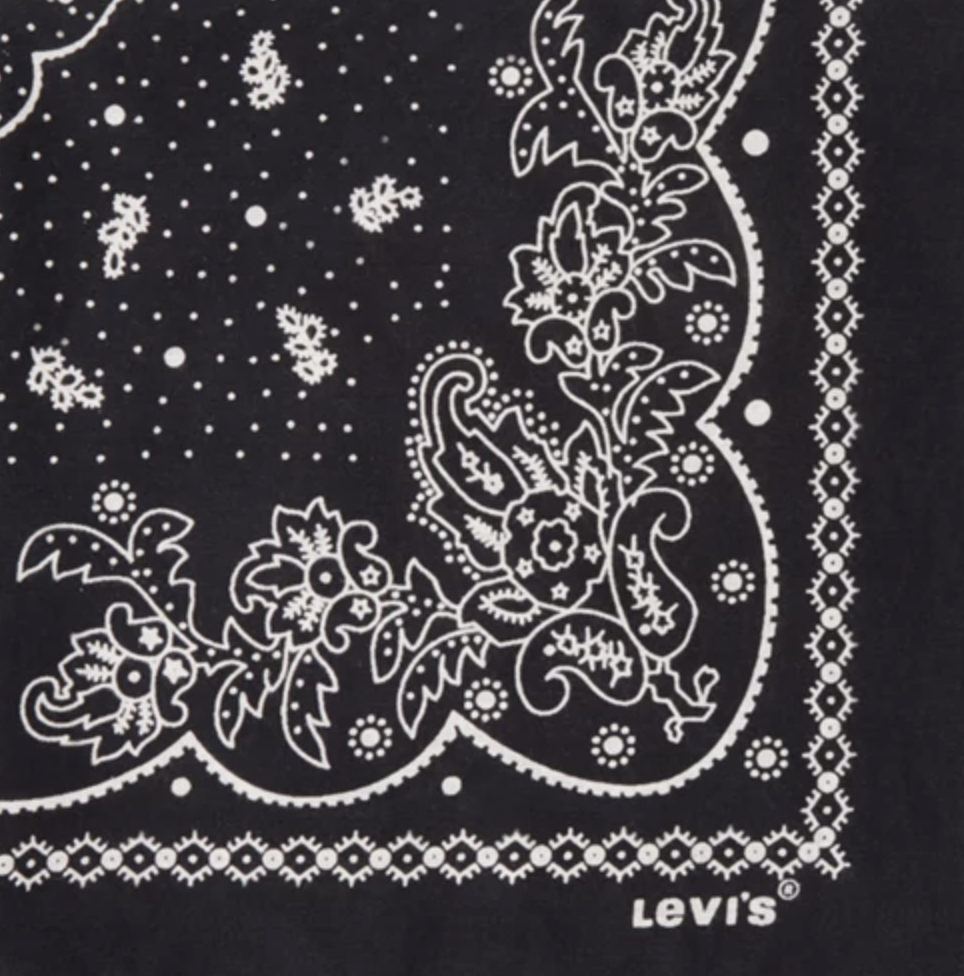

Cowboy’s Cotton Bandana

Paisley The Pattern Nomad

Script

Once upon a time is the way to start any good story, that’s not the problem here – instead, our difficulty is where in the world to pick up the thread of this? We could begin in India, Iran, or even Iraq, maybe London in the swinging 60s, in the Wild West, or perhaps in Japan, West Africa, Indonesia, or Uzbekistan. In fact, almost anywhere would be a legitimate starting point, because today’s episode is about a motif that has a good claim to belong to humanity as a whole rather than any one culture or set of hands. But we have to start somewhere, so this time the unravelling begins in Scotland

So I’ve chosen today, a Paisley shawl, which was manufactured in Paisley. And it is a large rectangular shape and it is from the 1840s, probably most likely 1842 to 1845 due to the brightness of the red colour that forms the base of the shawl. It has a plain centre and it’s surrounded by a border of Paisley pine patterns, which themselves are made up of different coloured floral symbols. This shawl is special to me because I feel that it exemplifies Victorian fashion in a way that most people don’t think about it because it is so bright. And also the vastness of the size of the shawl is really interesting. And it also is it pays a lot of reference to the original shawls produced in Kashmir India due to the colour and the patterns that are included in it. And I just find it such a beautiful piece.

That’s Lucy McConnell who is a dress and textile historian. And this is the third series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles which is called The Chatter of Cloth. In each episode, we start with a different textile and unravel its story. This time we are looking at the motif which is currently best known around the world as ‘Paisley’, although, as we will see that is only one of many names for it. Paisley is west of Glasgow in Scotland, Lucy lives there and as well as being a historian, volunteers at an old weaver’s cottage in the heart of this town which in the 1800s was transformed by these shawls. Paisley wasn’t the only or even the first place in Europe to produce these shawls, they started to be produced in the late 1700s in Lyon in France, Norwich in eastern England, and Edinburgh. And it was in Edinburgh in 1805 that a cloth merchant called Mr. Patterson, anxious to fill a big order for these wool shawls – turned to the Paisley weavers:

So Patterson chose Paisley because it had such a recognized, established history of textile manufacture here. And also the fact that the weavers in Paisley were used to adapt in their methods of production due to change in fashion. They were able to quickly employ different techniques, adapt their looms and things like that. So that was obviously attractive. But also due to the geographic location of the town, it had really good transport links on the river cart to Glasgow, and also Paisley was known to be able to produce things cheaper, much cheaper than other places. Especially in big fashion centres. There used different techniques that meant that they could produce things at much lower cost. And then that was, in turn, passed on to the consumer.

So Paisley was the Chinese textile hub of its day – able to undercut the competition with its looms, its skilled workforce, local wool, and good transport links.

So the shawl had a huge impact on Paisley textiles themselves did as well more generally from the 1740s, there were a thousand weavers residing in Paisley. And then by the time the show was at its height of production in 1834, there were 7,000 weavers, only weavers alone working Paisley and more people employed in subsidiary trades associated with manufacturing, the shawl. So the shawl itself, obviously just from those statistics, we can see impacted the population hugely. And this meant that the town expanded quite largely over a relatively short period of time encompassing surrounding villages and towns into its borders. And this is exemplified in the names of a lot of streets in Paisley. So there’s gauze street, lawn street, shuttle street, lots of different words associated with the textile trades, which is still in place today.

But this was an industry that at the start was very far from the large mills of later in the century. The weavers worked in their own homes.

So at the beginning of shawl production, it was very much a cottage industry and people were working in a kind of two roomed house. So they’d have their living space in one half and then a loom shop in the other half. But by the time there was an increase in the trade and machinery had changed. The jacquard loom come into operation. Owner managers were more involved in the trade and this altered the living and working environment, fish, all weavers, meaning that manufactories came into use. So these were a working space at the bottom, which would house around six to eight looms and then the weavers and their families would live above this. So rather than what we know is power loom, massive factories that were still on a relatively small scale, very artists and craft, but more people were involved in it. And because the technology had developed so much, it meant that more shawls could be produced on a larger scale again, to meet with a huge market and reducing costs and all the things that come with that.

To begin with weavers in Paisley used a draw-loom with a draw-boy to make sure the right shafts were raised. Later from the 1840s onwards they used the French invented Jacquard looms where the weft was controlled by individual pattern cards and the designs could be almost infinite. Efficient separation of the different processes designing, warping, beaming, weaving, tenting and fringing, meant that they were able to make shawls faster and sell them cheaper.

I think early in the production of the Paisley shawl the weavers did have a good life. They had a good income which was around 200 pounds a year at its height. But then as the century went on due to diversification, and they’re kind of taken away of their individuality as artisans, this reduced as weaving became a waged occupation as did the other subsidiary trades involved in shawl production. And that saw, the change in the industry from cottage industry to it kind of mass production

The demand for these shawls was immense, they flew off the shelves – for the Victorians the Paisley shawl was the equivalent of the mini skirt or the it bag – every woman wanted one and not just in Britain.

Everyone, every woman wanted one, essentially it was in Western fashion, the most desirable item, probably for the majority of the 19th century. And by 1830, the shawls produced in Paisley alone were reaching the amount of 1 million pounds worth in exports just for 1830. So that shows that it wasn’t only women in Britain that wanted them. It was across the world that were interested having them as the most fashionable item.

Paisley’s competitiveness and ability to produce lots of different colours and patterns meant that the emerging middle classes could afford them – they cost around 10 or 11 pounds – and just as importantly they worked well with the fashion of the day and the way people lived.

So by the mid 19th century, the crinoline skirt was hugely in fashion. And this was a vast hooped under-structure that went underneath the skirt, and this was deemed unsuitable to jackets and capes and things like that. So the shawl became something that was hugely popular for exactly that reason, to adorn oneself, to keep warm during the winter months, but also to show off your interesting fashion, your potential wealth as well, because the crinoline shape served as a perfect, beautiful canvas to lay the shawl across. And anyone seeing you, could see you were the height of fashion and could see the design of your shawl, reflecting the different changes, trends as we would look at them nowadays, in pattern, colour just from how it was draped and how it was shown across the huge skirt.

Queen Victoria is said to have bought 17 Paisley shawls in the 1842, and, in the way of these things, driving sales even higher. They started to appear in paintings and prints of the time. Women all over Europe were portrayed wearing their long-draped shawls with the famous tear drop pattern. One of the most famous pictures is William Holman Hunt’s portrait of his wife Fanny wrapped in her long red Paisley. The fashion also coincided with the start of mass migration from Europe with thousands of people seeking a better life in the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Many of them took their shawls with them, helping to fix them in our imagination as quintessentially British – an emblem of domestic and homely Victorian womanhood – and firmly gluing the name Paisley to this pattern. But that is about as far from the truth as its possible to be. There is nothing about the design we call Paisley that originates in the town, in Scotland or anywhere in Europe. The lovely curved tear drop motif arrived from thousands of miles away, where to this day it is a pattern held in huge affection and respect:

Well you know, in India, it’s, it’s so very common. It’s, it’s like a beloved sister or a beloved family member, so we’ve all grown up seeing it all our lives, you know, and it doesn’t just appear on textiles. I mean, it actually appears on our desserts. You know, so we have this dessert called the sun dish, which is from west Bengal, which is often shaped like a Paisley. We draw it on our festivals on the ground. You know, obviously it appears on all our textiles. I mean, there could be woven or embroidered or block printed or printed. It comes on hankies, it comes on our shawls. So we’ve all, we’ve all grown up with the Paisley. And, but because we’ve grown up with it seeing it everywhere, I don’t think Indians, I mean, other than, you know, the ones who know about textiles think about it too much about what it is and what it could mean.

Mira Gupta is a textile historian who lives just outside Delhi. In India the motif is often known as Buti, but Mira says most people call it KAIRI – meaning raw mango and you can see how it echoes that shape. For Indians it has a completely different set of feelings associated with it.

You know, I think somewhere in the back of our minds, we do know that it carries a spiritual significance. And, and it’s, it means many things that you do. I mean, it’s, it’s a symbol of fertility, you know, it’s also the yin and yang, which we have our own version of. And you know, we often incorporated it to some of our religious iconography, you know, when we draw things on the ground in some of the prophets. So it’s very familiar and a part of the everyday, but in India, a lot of our things are like that. You know, a lot of our spiritual things are also a huge part of daily life and which is one of the very charming things about India that, you know, for us spirituality, isn’t something that we keep in a drawer

The Kairi motif is now universal across India but it originated in the shawls that were and are traditionally made in Kashmir in the far north of India. They are made in a process that is as painstaking as it is beautiful. The yarn used in the shawls is fine soft Pashmina from the goats of Ladakh. And instead of throwing a shuttle, the handweavers use between 400-1500 spools of different coloured thread.

The loom is horizontal, but it’s, it’s twill, it’s a twill weave. But it’s more like brocading the whole process is more like brocading and they follow this system called the Talim. There’s a person who’s a kind of like he’s a leader of the shawl, weavers who, who calls out the colours. But it’s like a song, you know, so, and even carpets are woven like this. So he keeps calling off the colours and then the weavers weave the shawls based on the colours he’s calling out. And these weavers generally tend to be men. Well, they still tend to be men. And I think women follow, a very subsidiary role of sort of cooking and making the tea and all that, sadly, you know, so the weavers continue to be men and very sadly they’re not paid very well. I mean, they paid a fraction off of what the shawl is actually sell for eventually, you know, and weaving a shawl could take a year. It could take two years, you know, it could take three years. So it’s a very, very labour intensive process when done in the old fashioned way.

That is the sound of the Talim, being chanted to guide the weavers of shawls today. In the past these works of art were traditionally worn not by women, but by men and they had a very specific role in courtly and aristocratic life especially at the time of the third Mughal Emperor, Akbar the Great – who ruled in the 1500s.

Akbar had adopted this Kashmiri tradition which was also a Persian tradition of sorts because they looked to the Persian court for their cultural aspects and it was called Khilat. And Khilat is a Persian word, which means that you bestow robes on your favourite courtiers as a mark of esteem. So it kind of goes downwards, you know, so it’s not just the Mughal Maharajah who does this to his courtiers but the courtiers would do it their knights, I mean, just to take an English simile here. So the shawl became a very huge part of the Khilat ceremony during Akbar’s time and Akbar himself loved shawls you know, he was, he was a fantastic patron of the Kashmir shawls. And in fact, he used to wear two shawls, you know, have two opposite colours and then people in Kashmir felt that they could do better than that. So, then they started weaving double-sided shawls, which we call those Dorusha. So, now, because all these magnificent Shawls are being bestowed as Khilat, and Akbar himself was wearing them And as you know, the courts are normally where fashion’s trickle down from and trends. So everyone started getting acquainted with Paisley.

In those days the motif was not the same. It was more floral, then it became very elongated and then the tip started to bend over, and in other versions it became a sort of cornucopia, as Indian craftsmen pulled in design elements from China, Turkey and even from the botanical drawings being made in Europe. What is clear though is that across India – not just in Kashmir – they loved this, and the chintz makers, block printers, kantha stitchers and embroiderers of all kinds took the Kairi motif to their hearts. And then Europeans turn up in India in the late 1600s – in much greater numbers and the Mughal rulers start to bestow these hand-made Kashmiri shawls on the Dutch, British and French officials as Khilat, to show their esteem for them.

And then these officials would go back to England and obviously they weren’t wearing shawls, right. So they would give them to their wives and sweethearts and who, who loved them, who completely loved them. So that’s, that’s how they reached England in the first place. There’s a French strand in the story, so for some reason, a lot of Napoleonic soldiers settled in the Kashmiri area and they then carried back shawls to France. And, and so Josephine who was you know, was Napoleons’s wife, his wife happened to see these shawls and she loved them. And I think Napoleon also made her a present of, you know, like 20 or 30 shawls. So these two separate things were happening. So shawls reached England you know, because of the East India officials carrying them back and they reached France. And when they reach Europe, I mean, Europeans, couldn’t just couldn’t get enough of them. So I mean, and that affected the Kashmir industry very, very positively because you know, they have they started getting these enormous orders that they were not used to.

There are some glorious and slightly ridiculous pictures of British officials and other Europeans decked out in elaborate shawls and printed fabrics. One of my favourites is Captain John Foote by Joshua Reynolds, which I’ve posted on the web-page for this episode. But this sudden opening of the flood gates of demand, posed a problem, in fact two problems: first of all the Kashmiri weavers couldn’t keep up with the demand, every shawl took around 18 months to make, and secondly not many of the Europeans could afford the two to three hundred pounds the shawls understandably cost: which is where Paisley comes back into the story as the French and British manufacturers realised that although they couldn’t replicate the pashmina yarn they could make good shawls out of wool, more cheaply and much more quickly.

There is no comparison in the quality, you know, because one is handmade it’s made out of the pashmina, which is the finest and the warmest and the softest wool in the world, you know, the other is made out of well I’m sure a good quality wool, you know, but it doesn’t equal the questioner. It’s not as warm. it’s done on a, on a loom, so it’s not hand done. So, but these shawls are much cheaper than the Kashmir versions. And, and they have taken in London, Europe so much by storm that, that every you know, person at every rung of the social chain wanted to wear shawls. So, to answer your question it didn’t harm the Indian industry, but the Indian industry could not keep up with the demand.

So would we be right to see this beautiful motif as Indian in origin, rather than European? No – that’s not going to work either, as Mira explains the motif came to India from Persia:

It’s actually had a fascinating journey. So, you know, we were very lucky in the 15th century to have this enlightened Maharajah of Kashmir Zain al Abudin actually. And, and before that, there wasn’t a lot of craft in Kashmir not, not indigenous craft, but he was very keen on making Kashmir a centre of craft. So what he did was he got in touch with Persia, which was a repository of craft at that time, as you know, and he imported this Sufi mystic called Hamdani and Hamdani came down to Kashmir with about 700 disciples. And he actually trained, you know, along with the 700 people who’d come, many of whom stayed back in Kashmir, actually trained the locals in many of the Persian crafts, including shawl weaving.

And the Persians? There we can track back the design to the Sassanid dynasty which ruled in the third to the seventh centuries of the Christian era, where it may have originated as an important symbol in the Zoroastrian religion, a symbol of life and eternity. But it doesn’t seem to be Persian in origin either. Researchers and academics can track it to the ancient civilisation of Babylon. And now we are back in the mists of time, sometime between two thousand years and five hundred years before the start of the Christian era, under the rule of kings like Nebuchadnezzar. Here the Paisley motif was probably thought to be a representation of the unfurling date palm, a tree of life, which provided food to eat, fuel to burn, thatch for houses and fibre for weaving and tying. There is nothing simple in the story of this pattern, it doesn’t belong to any single culture or people and it holds a multitude of meanings.

India doesn’t own the Paisley either. I mean, India got it, you know, via Babylon via Persia. So I mean, Indian didn’t originated it either, you know, so I have no problem whatsoever. And, and I think it’s very healthy actually, you know, because After all, I mean, I’m speaking English to you. Right. You know? And I mean, I wear Western clothes, I eat pasta, you know, so I think these things in a, in a global world are very healthy that we should all learn from each other and adapt. And I mean, that’s what progress and civilization is about. Right. So, and especially something like the Paisley has been well, I, I believe even the Celts had their version of it. So I don’t think any one country can lay claim to it. I mean, I’ve, I’ve seen even a Japanese version.

Back in Paisley shawl production died out completely, seen off by a change in fashion as Lucy McConnell explains:

So fashion was hugely influential in the rise of the shawl but also in the demise of it, in the sense that the bustle skirt came into fashion in the mid 1870s. So this skirt rather than being a huge volume around the whole of the wearer, most of the bulk of the fabric is to the back of the outfit. And because it is so decorative in itself in the shaping that uses the large expanse the shawl, was seen as unsuited to covering this this garment, which in itself was designed to show off the fabric that the wearer was using to make the skirt, so short jackets and capelets came more into fashion at this period. And Shawls gradually went out of fashion.

Seen off by bustle, Paisley’s shawl production declined and instead the town became a centre for the production of sewing thread in large industrial mills. Kashmir fared little better, that is until recently.

So, the Kani shawls, which are the woven shawls had died out actually after the very late 19th or the early 20th century you know, when, when the market from the west dried up they had dried up, but there’s been very interesting revival in the last 20 years. And particularly by an English lady called Jenny Housego you know, who’s, who’s come to India and she started this company called Kashmir Loom. So there has been fantastic revivalism in the whole woven shawls space.

And perhaps we could end the story of Kairi or Paisley right here, but that would be an injustice to this pattern that every now again emerges phoenix-like and becomes the emblem of a new generation or way of life. In America, the cowboy’s bandana became one of the enduring symbols of the Wild West. Bandana is a word of Indian origin in itself, and the paisley motif was often used on the bandanas, these are now highly collectible. Speed forward to London in the 1960s and a new fashion for paisley emerged – but this time it signalled rebellion against old values, the birth of hippies and boho style. Rachel Mansi buys and sells 1960s and 70s textiles – although she says she is much better at buying rather than selling:

I think the resurgence of popularity of Paisley in the sixties is there’s so many factors that feed into it, but it seems to be, it’s a Bohemian sense. You know, there’s in the fifties and early sixties, everything was very sort of clean lines and modern and you know, that lovely post-war cleanliness and simplicity of modernism. And I think the Bohemianism of the sixties was a bit of a backlash against that. We’ve got the pop music going a bit more sort of psychedelic you’ve got Hendrix and people like that really creating these soundscapes that, you know, the people who were listening to that kind of music were also getting into sort of psychedelic drugs. They were getting into traveling the world opening fair, fair sort of perception. And you know, their awareness of the whole world was really opening up and broadening. And in parallel with that, you know, fashions became much more ethnically influenced.

But this was a very different Paisley – one that came in wild colours and was an extraordinary contrast to what had come before, Rachel says she can tell at a glance which Paisley is Victorian and which comes from the sixties:

Absolutely, the 19th century versions were much more sort of muted, earthy colours, burgundies sort of muted mustardy golds in the sixties. It was really an explosion. And I think that really ties in with the use of psychedelic drugs, to the desire for young people to really break away from traditions. The colours are much brighter. They’re really hot neon pinks, vibrant mustards, turquoise, and, and a real mix in one piece of fabric. Whereas I think in Victorian times it would have been more or warmish colours, you know, sort of grouped together so that it was quite harmonious and not really in your face, whereas in the sixties, they would Chuck it all in. You know, they’d be a bit of lime green, a bit of hot pink, a bit of mustard, but a purple and as well as the colours being really bright, the scale of the patterns I think was really increased, you know, so where you, might’ve had quite a small say motif in the, in the 1860s or whatever, maybe like, you know, inch long, little scrolls or laws in jazz in the sixties, you know, they’d be huge and they’d be mixed with florals, you know, really exuberant patterns where, you know, you can imagine the designers got completely carried away, just that adding in, you know, little floridly scrolls and flourishes all over the place and turning it into something that really would look quite spectacular and be very eye-catching.

And far from symbolising traditional Victorian values – or courtly rituals in Mughal India, this Paisley was about rebelling against it all.

I think it was really flipping it on its head. I mean, at that time you had men growing their hair long, you know, to great public consternation, people were horrified and shocked at the idea that you might look at someone and not be able to instantly tell whether they are a boy or a girl. So then you’ve got this whole androgynous thing happening, you know, men wearing caftans and tunics and women wearing trousers. And you know, that, that whole blurring of the gender sort of divide in terms of what you’re allowed to wear combined with the sexual revolution, where, you know, people, women had the pill, young women had a lot more sexual freedom. It was a massive rejection of Western traditional values and the wearing of wild, you know, colourful clothes was very much part of that. But you know that if you imagine someone on a psychedelic trip looking at a bit of pink Paisley fabric would have been quite a stimulating experience, you know, you’ve got these incredibly, they’re almost like fractals, you know, they’ve got these laws in patterns, but with these petals coming off the swirling lines that really lend themselves to listening to some psychedelic music and, you know, tuning out and disappearing into, into the kind of out of body experience. So I do think that everything ties together really doesn’t it in terms of what people were doing with their leisure time, in terms of the music they were listening to, the drugs they were taking and the textiles they were choosing to surround themselves with and to wear.

Today Paisley seems to have retreated in the West to the safety of men’s pyjamas and ties in sober greens and blues, with maybe a dash of red. But don’t be fooled, Paisley is the sleeping dragon of patterns, lying deep under the mountain, ready to wake and breath new fire into another age and another people who want to use it to symbolise new movements and attitudes. Paisley is a pattern that belongs to us all, part of our heritage as human beings, shaped and adapted by a multitude of hands down the ages. No one knows where it will turn up next and what it will mean to those who adopt it.

Thanks to Lucy McConnell in Paisley, Mira Gupta in Delhi, and Rachel Mansi in Bristol. For being so generous with their time and their knowledge. If you would like to find out more about them or about Paisley then you can find resources and links at www.hapticandhue.com/listen. You will also find a link there to the Haptic and Hue bookshop where the list called The Chatter of Cloth has a number of books in it related to this series. Each purchase helps this podcast. Thanks too to Bill Taylor of the Lark Rise Partnership who edited and produced this episode, and to all those listeners who helped to make this third series possible by supporting it via the Buy Me a Coffee button on our website. Next time will be a complete contrast, instead of looking at pattern that has roamed the world like a nomad, we will tell the story of a quilting technique that flourished in one small rural area and has remained firmly rooted there throughout its history. Meanwhile, thank-you for your company, and thanks for listening. I’ll leave you this time with part of a poem from the modern Persian poet Sohrab Sepehri who died in 1980. It’s called The Motion of the Word Life.

I and my gloomy heart,

and these wet windowpanes.

I am writing, and two walls,

and several sparrows.

Someone is sad;

Someone is weaving;

Someone is counting;

Someone is singing.

Life means a starling took wing.

What has made you unhappy?

Pleasant things are not scarce;

for instance, the sun

that shines there;

The child of the day-after-tomorrow;

Or the pigeons of last week.

Drops of water falling;

Snow lying on the shoulder of silence;

And time on the spine

Of the white jasmine.