Second Season: Episode #12

A Feeling of Resilience

This episode looks at the case for mending and thinks about how different cultures approach this, from the wool-rich districts of Yorkshire with their darning to the rural areas of Japan with Sashiko and Boro textiles, and onto Indian traditions of telling stories in Kantha cloth and making something completely new out of something old.

Thanks to Claire Wellesley Smith, who is a community worker in Bradford, West Yorkshire, Hikaru Noguchi who lives in Tokyo and is an expert darner now writing a new book about Sashiko, and Ekta Kaul, who tells stories of place, history, and belonging through thread and fabric.

If you want to see more of Claire Wellesley Smith’s work you can find it on her website: http://www.clairewellesleysmith.co.uk/ or on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/cwellesleysmith/. Her new book: Resilient Stitch: Wellbeing and Connection in Textile Art is published by Batsford and can be ordered from independent booksellers at https://uk.bookshop.org/lists/the-fabric-of-life. You will find a number of other wonderful books there on stitch and fabric curated by Elementum Journal. This page may only work for subscribers in the UK, but as soon as I have more information I will paste it here.

Hikaru Noguchi’s website is at http://hikarunoguchi.bigcartel.com/, and she on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/hikaru_noguchi_design. Her book called Darning: Repair, Make, Mend, published by Hawthorn Press, can be found at https://uk.bookshop.org/books/darning-repair-make-mend/9781912480159. Her new book on Sashiko is due to be published next year.

Ekta Kaul’s work can be seen on her beautiful website at https://www.ektakaul.com/. She is on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/ekta_kaul/. Ekta is running virtual courses on Kantha stitching and a variety of other classes over the next few months – you can find details at https://www.ektakaul.com/product-category/embroidery-masterclasses/

If you would like to sign up for your own link to the Haptic and Hue podcasts as they are released, for extra information and a chance to access the free textile gifts we offer with each podcast in this series, then please fill out the very brief form here. If you are interested in a long read or two or want to know why and how cloth speaks to us then you can find articles at www.hapticandhue.com/read

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name. You can see more of my work and that of other makers there or on the website.

Claire Wellesley Smith

photo by Carolyn Mendelsohn

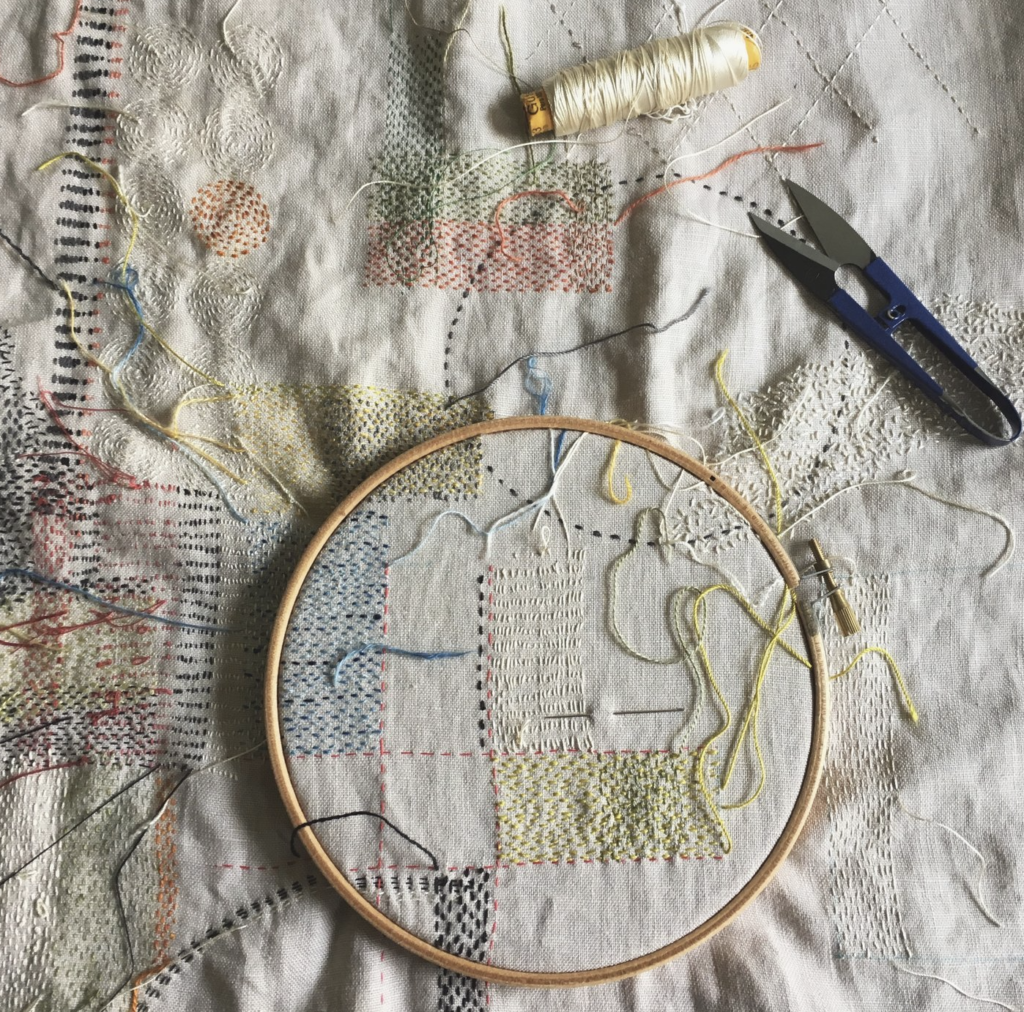

Claire’s Stitching

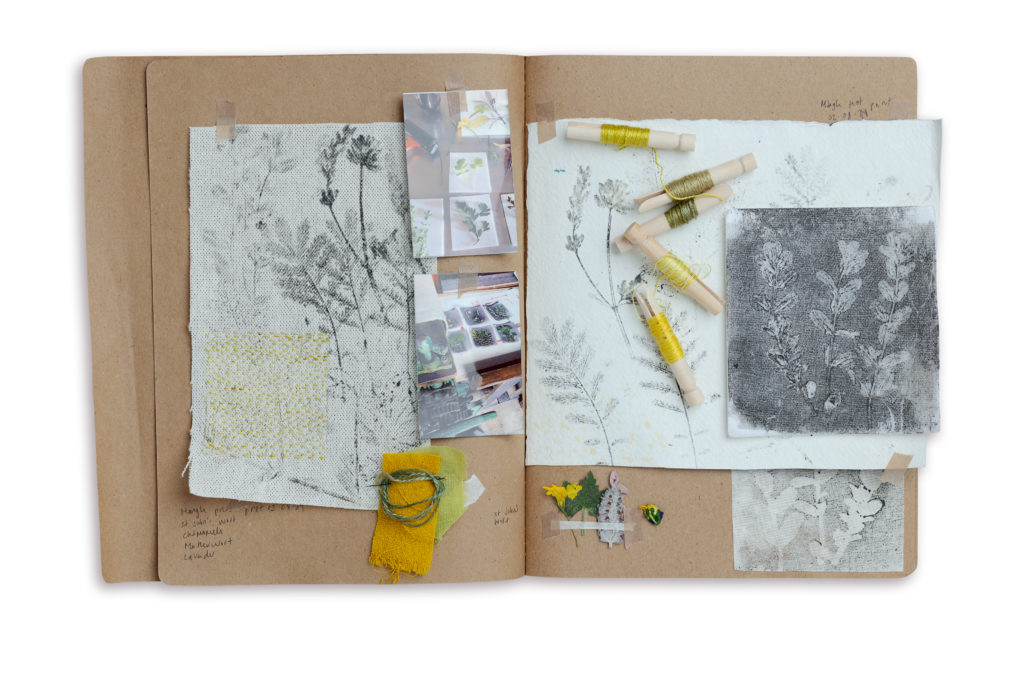

Claire’s Stitch Journal

‘Much Vexed Cloth’

Claire’s Resilient Stitching

The Hungarian Textile which

is Claire’s favourite

Claire’s stitching

Claire’s Stitching

From Claire’s new book,

Resilient Stitch

Ekta Kaul

Ekta’s stitch artistry

Ekta’s work in creating

stitch maps

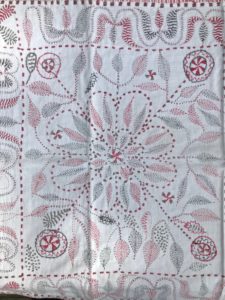

Kantha cloth

Kantha, something new

from something old

Kantha stories

Hikaru Noguchi

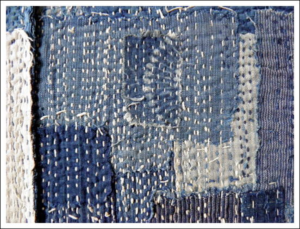

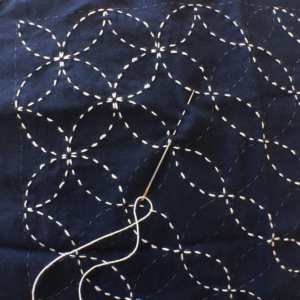

Layered sashiko, creating Boro cloth

Modern sashiko

Transcript

Every year 400 billion square metres of new fabric are made – that’s a number I have trouble picturing. 80% of garment workers are women and they earn some of the lowest wages in the world.

Point two: Oxfam says that from growing cotton to the dyeing process, it takes around twenty thousand litres of water, or over five thousand gallons, to make a single pair of jeans and one t-shirt.

Point three: Britons threw away an estimated 67 million items of clothing during lockdown last year.

I could go on, but most of us understand the problem here. We have gone from a time when cloth was expensive and difficult to produce and every scrap was precious, to now when the stuff is coming out of our ears – produced cheaply and discarded at will. We are the victims of our own technological success and so is the planet.

It hard for us as individuals, to know what we can do about this. One path is to buy less, much less and that means reverting to old skills.

Mending has been called a quiet and possibly futile protest against modern excess, but it’s lies within our power and it also has the capacity to open new doors for us.

I like to think about textiles as small storytelling objects that you can really unpack a story from the layers. But when you get an garment or a textile object, that’s been patched, reinforced, repaired, I’m thinking about, you know, the craft of use, the time and the life that’s held in those objects. And I suppose that gives them great resonance really, for communication and for comfort, that, that could hold a lot.

That’s Clare Wellesley Smith who has a new book just out called Resilient Cloth – For 17 years she has been a community worker in ethnically mixed and often poor communities in the city of Bradford, which is in the north of England.

So that work involves working with community mental health organizations, sometimes hospital settings, and community groups, , around the city. And I suppose, over that period, I kind of started picking up that the word resilient was used again and again in the context of health often, also in the context of communities, and that kind of flexibility, their ability to kind of absorb shocks and change. And so I suppose in my kind of movement around the city, you know, with a car boot full of textile materials, kind of working with really diverse groups of people, I started making connections between the idea of the flex and the ability to change, in the communities that I work in, and also in the way that you can prolong the life of the materials I like to use in my work.

Welcome to the second series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews, I’m a handweaver interested in how cloth speaks to us and the impact it has on our lives.

Each of the episodes in this series takes an emotion and unravels how we express that feeling in textiles. This time we are looking at a feeling of resilience, something that all of us have had to find in the last year. I wanted to understand the ways in which different people, faced with different materials, had made their clothes last a bit longer and in this episode we explore British, Japanese and Indian mending traditions.

We could have made it simple and left it there, but the further down this path I went, the clearer it became that it’s through mending and re-making that the stories of cloth are often heard most clearly. Repair tells us about the resilience not just of the piece of cloth we are holding, but it also tells us about the endurance of our families and communities.

I think we can learn so much from really ordinary objects, I suppose that the ordinary thing can, can become quite extraordinary through its lifecycle. I suppose I’m always interested in, that. And one of the things that I’ve really enjoyed doing with groups in my working life is, is, is asking people to bring things in, that normally they wouldn’t talk about. So we’ve challenged people, for example, to find the oldest garment in your wardrobe that you still actually wear and, and tell the story of that. And you get extraordinary details and stories about, you know, a dress that, , takes somebody sometimes through 20, 30, 40 years of their life. I suppose, I’m looking for the story, in the object or the garment, and I find that endlessly fascinating.

A friend of Claire’s, an antique textile dealer sent her an old quilt, which had no fewer than 17 layers. Claire unpicked it bit by bit.

The layers included pieces of garment you could tell came from plackets, and seams, interior seams, you could see shirts or dresses, pieces of darned wool, possibly old blankets, some, pieces that were really so used that they were literally shreds, but I suppose every layer, you know, adds to the loft of the quilts, and traps more air, it’s is an extremely practical thing. Going through these layers, you see also the fashions over time. There were shreds of Turkey red dye, cotton bits of Indigo print, tiny prints, what would be known as a conversation prints on cotton. I once read an interesting article that tracked the life of patchwork quilts and the time-span found in the materials. And I think they’d have reached over around a 40-year period. And when you think about maybe a family scrap bag, that would make sense to me. You know, things maybe that your mother or grandmother had carved the patches off, added into things maybe that you’d made yourself and having this collection of stories can be made by these textiles.

Claire calls this quilt archaeology, and there’s an idea here, which I have always found interesting, that repair and remaking by hand imbues an article with love, and acts in our minds as a powerful force for protection. There is a way in which the presence of the mender sits within the cloth, even if they are no longer with us.

Claire points out that in the UK certainly, and in many other societies as well, there is a strong generational divide around mending,

There’s a real difference in, different age groups in terms of how we think about repaired cloth. In a community-based project that actually explored the heritage of textile reuse and repair here in Bradford, there were lots of conversations about mending and repair as being essential. But that visibly repaired things were something to avoid. So invisible mending would be the thing that you would prefer to, show on a garment. And so I went along to a session one day wearing a heavily patched cardigan, and I’ve kind of patched it in multiple different fabrics around the elbows and pockets, and it became a bit of a talking point in the session. And the question that I was asked was why would I draw attention to the holes in that way? so, you know the preference really is to mend as invisibly as possible in a lot of groups. I think as a practitioner, I think maybe we need to address the privilege that accompanies some mending practices today, because in some communities, showing that you’ve, mended something rather than bought in new is a sign that you can’t actually afford to buy something new and that’s very problematic. I’ve had this conversation with my own mum about this. She’s particularly good at prolonging the life of her clothes. She made her clothes when she was younger. She she’s got some great textile skills, and yeah, invisible mending would definitely be her preference. yes, I’d say it’s a generational thing.

She says that you have to have confidence to show off a patch or a darn – but she believes that is gradually altering.

Maybe what’s changing around repair and reinforcing, , is that there are more conversations around now around consumption and excess and I think that, there is increased understanding about the global textile industry and production. But I suppose as a practitioner working mainly with communities, I’d say that communication around these issues at community level, is something that can be very successful. But you have to have the kind of projects really to get those conversations going. And so one of the things about working in an area that’s got, a huge tradition, a huge heritage of textile production is that it’s good to be able to reference a local industry. And then, you can look at how production of textiles and clothing has changed. It’s moved out of our cities, you know, to the side of the world, and the sorts of conversations you have then around, where we live today and how other people work in other parts of the world. those sorts of things are really valuable in how we think about a cheap t-shirt for example, or indeed buying second hand.

And there are few places in the world like Bradford for textile history. In the 19th and 20th century it was known as Woolopolis, the world centre of wool production bringing in fleece from all over the UK, as well as Australia, New Zealand and South America and turning out yards and yards of woven woollen fabric for suiting, coats, furnishings and everything in between. Interestingly alongside the production of new cloth in West Yorkshire sat the process of recycling and remaking old woollen cloth into something new. At the heart of this was the production of Shoddy – a term for cloth that had a proportion of re-cycled fibres in it.

There have been lots of projects where they’ve explored the weaving heritage, and, the wool processing heritage, less about the kind of other end of the industry and it’s quite, it’s a very dirty business. it’s the least glamorous aspects I suppose, of a big industry. The research I did into, it with, with community researchers and the local historian, Jenny Quilth, into the, heritage of the local recycling textile recycling industry, included my, reading a book by Samuel Job, called the History of the Shoddy Trade and it’s Rise and Progress to its Present Position. This was written in 1860 at the sort of height of shoddy production in the West Riding. And so he describes the system. Nothing is wasted, where even the dust that’s generated by the processes is sold on as fertilizer as it’s nitrogen rich, and it’s sent down to the hop fields of Kent. Anyway, he describes Dewsbury in his book. And, I’ve got the quote here as, “the famous rag capital, the tatter metropolis where every beggar in Europe sends his cast-off clothes to be made into sham broadcloth for cheap gentility, of moth-eaten coats, frowsy jackets, reeky linen, effusive cotton and old wool stockings. This is the last destination, reduced to a filament of greasy pulp by two mighty cylinders, the mix of much vexed fabrics re-enter life in the most brilliant forms”. And so I was really taken with this, this idea of the much vexed fabrics and, my own much vexed cloth, broken down textiles that I’ve worked on then returned t,o sometimes after long periods. I leave fabric outside sometimes, and the materials begin to break down, sometimes in, areas that I’ve printed due to the kind of processes used on the cloth. And so the cloth perishes. But it’s a very hands-on process, , a much gentler form of vexing. But again, one that uses things up and reinvents them.

Japan’s contribution to mending, Sashiko, is also a startling re-invention of cloth. It’s very different process from making Shoddy and this stems from the very different materials that Japanese people have had to hand. They grew and dressed themselves in cotton, linen and other bast fibres. These are garments that demand patching and reinforcing, not the darning of the wool rich communities in Europe.

Hikaru Noguchi lives in Tokyo, she was taught to darn by a friend in London and has written a book about it called Repair, Make and Mend which introduced Japan to the freer stitch work of darning. She is now writing a book about Sashiko, which she says can be tracked back to the 700’s and was originally carried out by Monks:

And that there was the belief that the spiritual calmness always affected the quality of stitch. So, if you are the good Buddhist practitioner the old stitches must be really beautiful.

Hikaru says that unlike western mending, Japanese Sashiko has always had two aims: one to repair but the second to please the eye:

So the decorative purpose of Sashiko and the mending purpose of Sashiko, it may be different, and the decorative purpose of Sashiko, of course, it’s the creation. So do more interesting patterns, but for the mending purpose of Sashiko people try to be discrete as possible. And that’s the mentality is the same as the Western, or I’m sure it’s all over the world because people try to hide the in their condition or the comment, I guess.

So we have the same sense of shame about having mended clothes in Japan as we see in Europe. Hikaru says it is a very long time since people in Japan have needed to reapir their clothes.

It’s died out completely. And so even I think my parents’ generation, their eighties the, they never habit that my mother come from the countryside and she never worn the patch or Don garment in her life or, or during the second world war or before after the Japan has been suffered for a very poor period, but then that’s only maybe 10 years or less.

A piece of clothing that has been heavily stitched or patched, is known in Japan as Boro, which really just means worn out or broken fabric. It came as a complete surprise to the Japanese, that western textile collectors not only loved these garments, which came from very poor farming areas, but were prepared to pay a good deal for them too.

The people think: what the Western textile lovers are really interested in these boro clothes and, you know, Yeah, so, and many people didn’t know that kind of things has existed. Like many of my student, if you’re, you know, sixties or 70 years old, and they haven’t seen anything like that, or they haven’t heard about it. And, and so it’s a really interesting, but I understand, I, I love Boro as well, I can feel human, the creative energy in those rotten layer pieces, and from stitching maybe the love in the family or, or yes, I can feel those stories in them and those stories really move to our audience.

It has taken time for Japan to understand that both Boro and Sashiko have made important contributions to their culture.

Japanese needlework lovers has done, so French style embroidery or American style patchwork, or the British style fisherman Arran sweaters, knitting, or the FairIsle sweaters, or Belgian lace you know, the Japanese ladies, especially ladie,s loved those Western styles for maybe 50 years. But I think the last 10 years Japanese people start to understand that the beauty of our traditional cultures not only Sachiko many others like young people start to be aware of. And, you know, that kind of the culture movement I think influence the textile or needlework lovers and they started to realize the Sashiko techniques is unique, Japanese wonderful, unique, and simple needlework techniques. And they just started practice, I guess.

And over the past five to ten years Sashiko has undergone not just a revival in Japan but it has taken the world by storm. Hikaru thinks that’s because very effective designs can be created with a simple running stitch. And she is unmoved that something so quintessentially Japanese has become a global practice – rejecting any suggestion of cultural appropriation.

You know, the cultural heritage stored in the story is really interesting for me. I think we just love other cultures, people enjoy Sashiko a lot, we are very practical about it and we don’t think about it being stolen. Japanese people can’t understand that because maybe we understand that Japanese, so-called Japanese culture, has been influenced from many, many different cultures. We always enjoy taking some element of other cultures. And after the war, the American cultures came and, you know, we understand the cultures is mixed or influenced from other cultures and we make own cultures. So, Oh, yes. I’m really looking for, to see new styles of Sashiko in other countries.

The great sculptor, Loiuse Bourgeois, came from a family of repairers, her parents were tapestry restorers in Paris. She said of her own work that assembling a sculpture “is a nurturing mechanism. . . it is not an attack on things, it is a coming to terms with things. . . . , there is the restoration and reparation . . . You repair the thing until you remake it completely.”

I can think of no better way to describe India’s great contribution to the re-use of old cloth

My earliest memory of quilted cloth is from those that my grandmother made, and that tradition of reusing old cloth to make something new exists in nearly all parts of India, it might be referred to by different names. So in Bengal, it’s all Kantha, but in the North where I grew up, this was called Guteri, which were very lightweight quilts that were made using stitch and kind of stitching multiple layers of cloth, which my grandmother loved, particularly not just because of its lovely feel as you slept in the summer nights, but also because it held a lot of memories, you know, looking at the pieces, you could always recount stories.

Ekta Kaul grew up in northern India – the daughter of two scientists – both her parents were academics focusing on insects. But her mother and grandmother were also passionate about textiles which had a profound impact on Ekta. She trained at the National Institute of Design in Gujarat, before coming to Scotland as a post-graduate. In her intricate work, she makes incredibly beautiful stitched pictograms and maps, which to my eye seem to connect directly to Kantha.

I don’t necessarily look at it as simply taking the tradition of Kantha. However to me, it’s, it’s the idea I’m pursuing that is important, which is that of, you know, stories of place and mapmaking and finding meaning and the memories. But a strong connection to my heritage through Kantha feels significant. And I have loved running stitch, you know, ever since I can remember, and it’s called by different names in various cultures, but I love the simplicity of it. And the fact that you know, it seems to travel between these two or three different layers bringing multiple layers together as quilting or on a single layer. It can be a line as a texture. It could represent, you know landmarks or water bodies or legs in the way that I like to use it. And to me, the fact that it, it is something that kind of takes me back to my culture. My heritage is rooted in Kantha is another beautiful layer of the whole, it’s not the primary driver, but it’s I think, a meaningful, significant part of it.

Kantha involves taking old cloth, anything from frayed silk saris to worn-out cottons, and stitching them together in swirling coloured designs to make something new. Unlike darning or Sashiko there is no sense of embarrassment about Kantha in India.

But as you rightly said, the association of those two are rooted in shame, but it’s completely different to what Kantha represents. In India it is very much about a celebration, you know? So, the fact that you’re using you using old cloth is something that can be understood in the larger cultural context. What I mean by that is the idea of repurposing. The idea of very deep respect of materials is, is still rooted, in, kind of it’s the DNA of the Indian way of life that you would never consider throwing anything away because it’s considered, you know, a big waste of resources.

So if you, if we look at food, so I remember my mother, you know, using the using leftovers, but kind of transforming them in a completely different dish the following day, it’s the same sort of attitude to fabric, which is about repairing or mending old, or not even old, whatever needs repairing your first instinct is to restore it, to repair it, to mend it. So whenever there was a big occasion in the family, or like an important rite of passage, whether it be a birth of a new child or a marriage in the family, or the arrival of honoured guests and a Kantha given as a present, it was something that a mother would start at the birth of a new baby or a grandmother would give the baby to be wrapped in. So it’s very much associated with gifts, with celebration and it’s, I think the complete antidote to a feeling of shame.

There is also a much more overt sense in the Kantha tradition of these pieces of cloth telling family stories and expressing future hopes.

You know, just the importance was that it was made of textiles that once had a previous life there, they were things that were used within the family or belonged to a much loved and cherished member of the family and it was being passed down the generation. So that there was a sense of it being an heirloom that you would look after and when they passed on is very much associated with it. Also, it’s seen as an inventive expressive art, you know, where you’re expressing stories from everyday life, you’re embroidering your hopes and dreams for the child, for the new child, or for your daughter. And in that sense, passing it on as a blessing. So I think the theory that it was second-hand doesn’t hold true. I often like to think of it, as you know, in, in Indian philosophy, you would, you would talk about rebirth and multiple lives. And it’s also connected with that idea that you know, a cloth lived a certain life, and then it’s being kind of rebirthed into something new, and then it’ll go on to kind of live a whole other life, but with, you know, kind of flavour of its previous existence, isn’t it

And these are stories that have not been heard so clearly, the stories of women – often women who were could not read or write and yet they could outline their story and demonstrate their artistic ability in stitch:

So to me, they are such strong examples of individuality of expression and of a feminine universe. I mean, I get so excited that if they were all done by women and kind of how women viewed the world, how they interpreted it, how they express themselves through it it is just so fascinating.

Kantha like Sashiko has travelled all over the world. I can walk down the high street of my small town in Dorset and see Kantha cushions in the windows of one of the gift shops. It made me wonder how Ekta thought about these very personal textiles effectively being sold to people who have little understanding of what they might mean. But Ekta says the history of textile exchange between India and Europe goes back for over a thousand years, this is just one more example.

So now that, you know, you are seeing cushions, for instance in England, I think it’s something worth celebrating. It means that some of the connections that were lost are being restored again. And it may be that you know, they might seem to be made by hands that are not necessarily expressing their personal experiences, but we can look at them in the context of a generation of a woman or a man sitting and working on something that is meaningful, that is going to go to another country and hopefully bring joy and colour to somebody’s home. So I feel that it is the response of the Indian artisans to the present times. And it still means that hand embroidery continues and it’s not kind of died out. But, the way our lives are now, with the digitisation of things, isn’t that lovely to actually have something in our homes that was done by someone rather than, you know, being produced by multiple machines. So, I see that as something worth celebrating,

Textile mending and remaking is a complex thing, much more complex than we think at first sight. We might think we are just prolonging the life of a piece of clothing, but we are also enjoying the nurturing activity of stitching, and we are telling new stories with old fabric or keeping alive family histories. Here’s Claire talking about one of her favourite textiles:

It’s a piece of, Hungarian embroidery, and it now looks at my house and I actually, I was looking at it through the day and it really, really needs repairing again, but it’s a piece of white linen, with red cotton, traditional embroidery, folk art motifs, and I think it was probably originally made as a cloth to put on a side table, and it’s moved around. Um, it came from my great grandparents’ apartment in Budapest where they left it until, they fled, during the Second World War. And it ended up in Australia with my grandfather and I have a photograph of myself as a toddler, um, visiting them in Sydney. Um, and it’s over the back of a very 1970s, um, sofa, and then it moved onto my Mum’s dressing table and it was there through my childhood. And you can really see the kind of the front side of the embroidery got quite faded at that point. So the thread is a lot less bright on one side, and then she gave it to me. So for me, I suppose it speaks to my family and it tells story of their movement during the 20th century. And it’s a story of survival, many of my grandfather’s family didn’t survive the war, and it’s heavily darned around the edges. So, it kind of tells a story that people have been bothered about it. So they’ve wanted it to kind of, to have continued use over time. Um, so yes, that would be my, probably my favourite.

Part of what Claire calls the tenacity of material and the messiness of life.

Thanks to her Ekta, and Hikaru for sharing their thoughts. I hope it helps cast some light on why we enjoy this and how we might use some of the materials we have at the back of wardrobes or the bottom of mending bags.

If you’d like to look at pictures of their work or see links to some of the books that I found useful then please go to the page for this episode at www.hapticandhue.com/listen, where you will also find a full script of this podcast and a form that enables you to get these podcasts directly in your inbox, which gives you a chance to win the textile-related gifts I give away with each episode. If you feel able to rate or post a review of Haptic and Hue’s podcasts it’s always a help and it will enable others to find it more easily too. Next time we will be going back to wool and sheep and tracing the fate of fleece from the back of a sheep and tracking its journey to arriving on the back of a man or woman in the shape of a smartly tailored jacket.

Thanks for listening and I will leave you this time with a poem from Hazel Hall an American poet from Oregon who died in the early part of the 20th Century.

Here are old things:

Fraying edges,

Raveling threads;

And here are scraps of new goods,

Needles and thread,

An expectant thimble,

A pair of silver-toothed scissors.

Thimble on a finger,

New thread through an eye;

Needle, do not linger,

Hurry as you ply.

If you ever would be through

Hurry, scurry, fly!

Here are patches,

Felled edges,

Darned threads,

Strengthening old utility,

Pending the coming of the new.

Yes, I have been mending …

But also,

I have been enacting

A little travesty on life.