Second Season: Episode #10

A Feeling of Transformation – Part 1: Performance

Mark Twain once wrote: “without his clothes a man would be nothing at all; that the clothes do not merely make the man, the clothes are the man; that without them he is a cipher, a vacancy, a nobody, a nothing… there is no power without clothes.”

Clothes cover us and warm us, but at the same time, they reveal what we want to say about ourselves as well as the gap between how we’d like to be seen and how people actually perceive us. This matters to actors and this episode looks at how actors study the tiny details of clothes and costume to help them deliver great performances. Alessandro and Emily share the secrets of the work and thought that goes into their performances.

With thanks to Emily Mortimer and Alessandro Nivola for their time and thought on the subject of clothes and what they do for us. The transcript of this podcast is below the pictures.

If you would like to sign up for your own link to the podcasts as they are released, for extra information and a chance to access the free textile gifts that I’ll be offering for each podcast in this series then please fill out the very brief form here.

If you are interested in a long read or two, or want to know why and how cloth speaks to us then you can find articles at www.hapticandhue.com/read

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name. You can see more of my work and that of other makers there or on the website.

Alessandro Nivola and Emily Mortimer

Lady in Waiting, Elizabeth

Regency Buck, Mansfield Park

Lunch went down the dress

Flower Seller in Hugo

Costume design by Sandy Powell

Mary Poppins Returns

Not that pony

And not those shorts

Alessandro as Mr Dean, Black Narcisssus

Mr Dean, Black Narcissus

Mr Dean, Black Narcissus

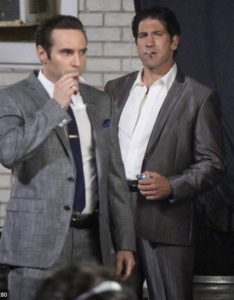

Mobster and Family Man,

The Many Saints of Newark

Emily, as herself.

Alessandro as himself

Mary Poppins Returns

Emily back left

Transcript

Every now and again you watch something on TV, film or, in the old days, on stage, and even though you knew a certain actor was in a show, you couldn’t see her or him, because so completely had they assimilated the person they were playing, they themselves had become invisible.

These performances are exceptionally powerful. And the demands it makes on an actor must be high, they become shapeshifters, moulding their features and personality into another being with a different history, another personality, and outlook.

The performances I’ve seen where it happens are rare: Laurence Olivier could do it, Kate Winslet can, and I’ve seen the actor, Mark Rylance do it on more than one occasion. This is at the heart of what we ask actors to do when they play a part, create a performance, and tell us a story.

This episode which comes in two parts is about how actors achieve that metamorphosis and the role that textiles play in helping them cast a spell in the essential make-believe of the stage and the film set. It looks at how costume helps create performance, what fabrics do to conjure the illusion, the suspension of belief that is needed. And then in the next episode of this podcast, we go behind what we see on stage and screen and look at the hidden hands that create the illusion, and hear from the costume designers and the breakdown artists who put their hearts and minds behind what we see.

Welcome to the second series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews, I’m a handweaver interested in how cloth speaks to us and the impact it has on our lives.

Each of the episodes in this series takes an emotion and unravels how we express that feeling in textiles. This time we are looking at a feeling of transformation.

It’s quite sort of ephemeral and strange the business of getting ready to do it, to become another person. And there are no real rules about how you approach it. And, and sometimes you can feel quite, you can feel quite at sea with it’s all. But it’s not really, until you go into the first costume fitting with the costume designer, that you actually start to sort of get your teeth into something that feels tangible and, real, and it really is where you begin to start to understand who the character is and use you, you go through, you know, the very first stages of talking about what the person might wear and, and it, it often is that you realize you do have an instinct.

That’s Emily Mortimer, an actor familiar to many for her roles in several well-known films, including the perfect woman in Notting Hill, Kat Ashley with Cate Blanchett in Elizabeth, Woody Allen’s film, Match Point, Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island, the 2018 film, Mary Poppins Returns, and she both directs and acts in a new BBC series of Nancy Mitford’s heartbreaker, The Pursuit of Love, which will air in the UK in the next couple of months. Emily says that costume is a vital element of any performance.

Yes, it just totally does shapeshift you when it’s the right costume and you feel that everything’s working in, unison with itself, you feel completely confident to go and, not have to think about it. It makes you walk a different way and it makes you talk a different way and move a different way and behave a different way when it’s right. And when it’s not right, it’s awful. And when it’s right, you don’t have to think about it. You’re just, you’re just being helped to step into this new person’s skin. And, um, and everything becomes easier, but when it’s not right, everything becomes harder and you’re battling against it and you aware of it and you’re worrying about it.

Every actor has a different way of grabbing hold of the corner of a new person and pulling on it to start the transformative process. Emily begins with books and research, Youtube and Google. Others do it differently.

Yeah. I mean, when I get offered a role, I often like to get in touch with the costume designer very early on in the process. It’s one of the first contacts that I request. And, um, I, and a lot of times the costume designers are the ones who are the first people to send me visual references for the entire world of the movie, not just the costumes of my own character, but for everything about the world of the movie. And especially if it’s a period, but whatever a milieu it might be. They’ve obviously, usually they’ve been hired before I have, and they have done a lot of research and have all these boards of photographs of inspiration for all the different characters mine included and for, um, the whole kind of, um, surrounding atmosphere. And so, I try to get in touch with them quickly and then ask them to just send me everything that they have so that I have a sense of, of all the different people and everything that, that the style and feel of the, world that,the director has in mind. And so, um, yeah, I would say it’s just a huge, huge part of, of character because I think that the way that people dress affects the way that they are physically, um, the way that they move, and it’s always a very strong reflection of a lot of things that are going on psychologically with the character. So, um, it, it really is a very high priority for me.

That’s Alessandro Nivola, who is Emily Mortimer’s real-life partner. He is a successful actor who has played a huge variety of roles from starring opposite Helen Mirren on Broadway to being in Jurassic Park 3 and British costume drama. He was in John Woo’s film, Face Off, playing Nicholas’s Cage younger brother and in Selma, the film about the US Civil Rights Movement. British audiences have seen recently him playing Mr Dean opposite Gemma Arterton in the TV remake of Black Narcissus. That film was first made in in 1947 by Pressburger and Powell with David Farrar in the role of Mr Dean:

Um, well, first of all, um, Black Narcissus, uh, had, um, one deal-breaker as far as costumes went, which was that David Farrar in the original spent most of the movie in these very short little shorts. And, I told the director that, that, that there was no way I was doing this movie if that was going to be the demand. There were two things, there were the shorts and the three-foot-tall pony that he wrote. Um, and, um, so the costumers were, uh, you know, forced to find ways around the, uh, original reference as far as that went.

So no pony and no shorts but there was something important about the character of Mr Dean that Alessandro wanted to get across:

it was very important to me to, draw the audience’s attention to, Mr.Dean’s World War One experience because although he doesn’t make a lot of reference to it and he doesn’t really explain to Sister Clodagh, why he’s chosen to kind of step out of English life and, move to this remote part of the world. It seemed like some kind of war trauma had a lot to do with it and, something that he’d experienced while fighting. And so as much as possible, we wanted to keep making reference to that. And Dean had a lot of, things that were leftover from his soldiering, stuff that he wore during the fighting. And so, you know, I had boots and, pants and hats and things that had been, that I’d worn during, during my work experience, my experiences as a soldier. So, and, you know, and then the props guys too, I can’t remember it all, but like, my gun was something that was issued from that period and, as much as possible that was there to kind of keep, suggesting that, that, that experience had had a big impact on, on him emotionally and psychologically.

And here is one of powers of cloth and costume for actors inhabiting another person – they can express things that aren’t spoken:

Yeah. And, and also, I mean, they’re not always things that the audience will even pick up on. I mean, sometimes they’re just things that, um, remind me of something that’s important. Uh, you know, that might be an obsession of the character or something that the character is fixated on. Anything that kind of keeps drawing your own imagination back to those things that are specific and personal to the character. Um, just root you in the reality of the, of the world and the person that you’re playing. And so it’s not all for the sake. It’s not all for the audience. Some of it is just for you.

Both these actors understand that although in one sense clothes conceal us, they also reveal us in a much greater way than we expect, and for actors, engaged in translating themselves and making us believe in that – it’s a gift. Here’s Emily:

What you’re looking for is clues is to, um, I mean, just from the way that people wear that clothes in real life, you can tell so much about somebody just from the clothes that they choose to wear. And, I think it is a combination of sort of things that you yourself are aware of, and you’re doing as a kind of presentational thing to the world to show who you are as a person, but then there’s a gap between what you think you are coming across as, and then what you really all coming across as, it’s something a little bit different because you’re, you’re revealing things about yourself without meaning to all the time. And I think the clothes one chooses to wear are exactly a manifestation of that, and so that’s what one is constantly on the lookout for when you’re trying to kind of do the detective work to work out who this person is, and then to find out what the problem is. And, the problem often manifests itself in a way that people are unaware of. And, that’s interesting. And so there are two things going on, in every part of sorts of, assessing and, and working out who the character is, the gap between how they want to be perceived and then what they are really perceived as without realizing. And I think that’s, that’s a really interesting process and, and definitely, costume is a major, a major part of that. It’s a giveaway, it’s like a tell, you know, how people choose to dress themselves.

For Emily the difficulty can lie not in having to play someone who is very different from you and but with someone who is close to your own personality.

You have to be careful because sometimes often when you’re not quite sure who the person is, and that they’re not a million miles away from who you are, you tend to just go for things that sort of look good on you rather than things that. I mean, obviously, you want to look good, of course, one does, but that’s not what you might wear in real life, is, is not the key to becoming, another person. And so sometimes it can get quite confusing if it’s something that’s set in the sort of, you know, now, and you’re playing somebody that might not be a million miles away from you, you have to kind of force yourself toe kind of go outside your comfort zone, as they say. And, wear things that you, you, you yourself wouldn’t wear in a bid to find who this other person is.

And then there are the moments when actors decide that it’s time to use costume to go in an unexpected direction and come up with something completely different, especially if, like Alessandro, you are playing a gangster alongside Nicholas Cage in John Woo’s film Face-Off.

I was playing Nicholas Cage’s younger brother. And, in the script, he was originally kind of a mini-me of. They both were described as having kind of leather pants and being these kinds of clubbing criminals or whatever who were, kind of sleazy or whatever. And, I knew that I could never like out wild at heart Nick Cage and, um, so that maybe I should go the opposite direction. And so when I arrived at my first fitting, they had all of that kind of like leather coats and all that kind of thing. And I told them that I wanted to look like Woody Allen and that, um, I needed wide whale corduroy and sort of, you know, boat shoes and like sleeveless sweater vests, and glasses and yeah, and they were kind of baffled by that, and sometimes on these movies that are so huge, um, nobody’s really paying attention to what you’re doing until you’re on set and the camera’s rolling. And so you can get away all kinds of things before people realize that you’ve kind of taken a left turn. And, so they dress me that way. And I showed up on set the first day and I was kind of paraded in front of John Woo to get his approval before we started filming. And I was clearly just not at all what he had in mind for this character. I mean, just nothing like the way that he’d conceived it. And he, um, I remember him sort of looking me up and down a few times and he, you know, he’s a very hard man to read anyway, but he then nodded and he said, okay, but you will have machine gun. And as long as I had a machine gun, he was okay with it. Um, so I was, I was Woody Allen with a machine gun.

Both Emily and Alessandro have played a good deal of costume drama from Jane Austin to 16th-century royalty, from bustles to corsets and it all carries with it its own kind of pain, especially for women:

They have to get your waist tiny and they have to, and you’re quite grateful for that often, um, you know, the need for the tiny waist, cause it just looks better in those costumes, but it is agony and, you know, miserable, and then there’s a great sort of sigh of relief when it comes to lunchtime when you can get, but it takes sort of 10 women normally to sort of undo all your stays and your corsets. And it takes another half. ….I’d basically have five minutes for lunch, you’ve got to undo it, loosen it in order to eat and then you have to tighten it in order to get back on the set. And, um, it all takes a huge paraphernalia and long, long time. And, so that is quite miserable. And then, some of them are so sort of conscientious about underwear, and say you didn’t have the kind of the bras that keep your boobs up in those days. And so you sort of have to wear these terrible bras that make your boobs miserable. And then sometimes you find yourself thinking with these sort of 1930s knickers that I’m wearing, ’cause I’m not sure that I feel that great about them. Um, but yeah, it’s also someone else’s knickers from the 1930s I’m sort of uncertain about.

But at the same time as the old-fashioned underwear you are also wearing a good deal of modern technology:

But then, then there’s all sorts of other things going on underneath because you’ve got, you know, you’ve got your sound pack and your microphone wire, and it’s all sellotaped to your bare skin half the time and running down your leg and down your trouser leg. And you know, you’ve got a million sound men sort of going up your skirts, trying to turn on the battery. And so there’s, there’s a lot going on underneath one’s costume, not just, not just ancient underwear,

And then there are the times when things go wrong:

I guess it’s sort of partly just the experience of doing the job maybe, but I have traumatic memories to do with costumes often because I’ve sort of slightly ruined them because as Alessandra will attest, I spill things easily. So, I do remember on Elizabeth, the movie of Elizabeth, which was Cate Blanchett’s, sort of big entry and entree to the world. I was her head… chief lady in waiting, and we were wearing all these extraordinary, really beautiful Elizabethan, you know, dresses with millions of petticoats, we’re in these exquisite clothes that must have cost, I mean, the material well itself, it was all imported from India, because it was directed by Shekhar Kapur. So, there was a lot of sort of Indian influence in the costumes and the set design and, and, um, Alexandra Byrne, who’s a famous costume designer, who has won Oscars and been nominated many, many times for awards designed the costumes. And I know because I met one of her assistants recently that she still talks about me spilling my lunch all down my, um, my outfit and, uh, in Elizabeth and, um, and how just sort of disgusted she was by the fact that, I had all but ruined one of these just sort of exquisite, extremely expensively made, one of a kind, sort of Elizabethan pieces. And, um, and the whole crew, the whole cast after I had this terrible incident with my lunch, uh, was forced in a really kind of humiliating way to wear bibs. And, um, and everybody hated me because of it, so I have a sort of trauma about it because I forced them into wearing these bibs.

And then there are the pleasures of working with people like Sandy Powell, who is the acknowledged Queen of Costume Designers.

It’s so amazing getting to wear one of her costumes and see how she works. And it’s just, you know, because very often, if the costume designer is sort of less than, um, you know, not, not, not, not such a superstar costume designer, there are times when you can feel a little bit anxious that maybe they’re you, that, that you’re the one that’s going to have to be kind of leading the charge in terms of finding the right look for your character. But when it’s someone like Sandy the detail to which she’s already thought about who your character is and how your character fits into the rest of the, of the piece and the world and the colours that you would never ever put together, yourself, because they’re brave and they’re odd. And yet they kind of somehow sort of sing on camera in a way that if, if it was something that you’d put together, it would never work. And she’s just so brilliant. And so it’s such a pleasure being, given one of her costumes to wear and going through the whole process of choosing what to wear with her. It’s really, you know, one of the great sort of treats of my life has been working with her.

It’s easy for us to think the clothes are being used just to create a new carapace for the actor to inhabit, and it’s an odd thing trying to become someone else, trying to cast off or repress your own being and assume the mask of another. In some sense, it could slightly be frightening or liberating. What Emily and Alessandro are saying though is that, it’s the textiles and the costumes that carry the weight of bringing out underlying feelings and truths that make up a person – things that might be hidden or which cannot be articulated but are transmitted to us by another means entirely, somethings that exists outside words but can be commandeered by a thoughtful actor to form the foundation of what they do in conjuring a performance.

This turns on its head my understanding of clothes. We perceive them in their most elemental form as being there to cover us, to warm us, to conceal us, but what actors understand is that they reveal us instead:

Last year I, I made this mob movie, that’s a prequel to the Soprano’s series. It’s called the Many Saints of Newark. And, you know, there was actually quite a lot of variety to the clothes of my character because on the one hand I was playing a kind of, you know, violent thuggish person. But on the other hand, um, somebody who is really stylish. And so there were times, you know, I had a range of things from like just impeccably tailored suits and, and, um, you know, a lot of kind of jewelry and tie clips and everything was coordinated, you know, cause cause Italian Americans who were kind of flashy in the late sixties tended to really like have everything matching. And, um, and so there was that, and then on the other hand, there were, was this kind of like home life that was really, um, kind of just the total opposite of, of that kind of peacock vibe where, you know, I was wearing like singlet uh t-shirts and, and these kind of like really ugly, um, kind of knit short sleeve shirts that had kind of a vertical stripe, big garish, brown, vertical stripes on them. And there’s these two kind of different ranges of presentation that were really important from scene to scene in terms of what the character was trying to convey at any given time. And sometimes, I could just say to the costume designer, I think he needs to come across as a little bit like insecure or pathetic or, you know, less, you know, confident or macho or something. And then there, you know, we would find something that was still in his wardrobe, but that didn’t feel as, you know, like much like his chest was puffed out, or, or this is a scene where I really need to like dominate the other character physically. And so we would find something that just like made me look as strong and intimidating as possible. And so, and then, you know, there’s a million other shades in between, but like within one character’s wardrobe, there can be clothes that reflect all these different kinds of states that, you know, that the character might be in depending on the situation and who the other characters are that, um, he’s interacting with. And that process is, you know, I’ve found that costume designers really love that and, and love being aware of, of those concerns, even if like it’s not something we would necessarily even share with the director.

Both these actors think a great deal about the costumes and even the fabrics they wear and how to use them, because they know how important they are when the moment comes and they are on set:

Everything about being able to sort of give your best performance on a set, you know, when the cameras are rolling you’re not having to think about anything, but listening to the other person and responding to them feeling like you can, you can be that and you can relax and, and listen and respond. And, um, and, but in order for that to happen so much work has to have been done previously leading up to that moment to stop working and stop worrying and just be there and perform, all this money, all the research you have done and you’ve thought about it and talked about it and, you know, sort of dreamt about it and worried about it and read about it. And, everybody that has to have done all this work including, importantly, the costume designer and if, if they’ve done it right, and all the work has gone in that should have been gone in and, and a bit of inspiration too, then, you just don’t have to think about it. And that’s, that’s the that’s, that’s when you can give your best performance.

Mark Twain wrote in his 1905 short story The Czar’s Soliloquy: without his clothes a man would be nothing at all; that the clothes do not merely make the man, the clothes are the man; that without them he is a cipher, a vacancy, a nobody, a nothing… There is no power without clothes.”

The challenge of acting is trying to be as specific as you can about character. That’s where, I mean originality comes from. The more specific something is, it’s those details that um, bring out the reality, because people in real life have so many little specific attributes and, um, good costume designers are really highly attuned to that. And I’m always amazed at how much detail has gone into, um, the design, both on, uh, with, with clothes and, and with, um, sets and everything. And, and it can’t help, but kind of catapult you into the reality of that world.

Both Emily and Alessandro are fiercely appreciative of the skill and eye for detail that talented costume designers bring to the set and stage. And next time that’s where we are going to hear from a costume designer and a breakdown artist about the huge variety of techniques and skills that going into what you see in the final production. Here’s Costume Designer, Sinead Kidao, talking about one costume she helped to put together for Walt Disney’s 2017 version of Beauty and the Beast, which starred Emma Watson in the role of Belle.

It’s a red cape and it’s one specific costume, but our breakdown and dying department, they actually made their own blocks to do block printing. We had I think there’s like 16 different fabrics involved in the whole costume, but some of the wool that we used was like a vintage Jacob’s wall that had been bought in a market. Another one of the linens we used had been sourced at been someone’s textile project from the 1960s that Jacqueline had sourced on eBay. And then that was over-dyed using madder. And then we use like a piece silk, which was sourced from India that we’d sourced for another project, but then that was blocked printed in our, in our work room. We we used some different vintage textiles. Hand-Woven like caddy cotton. I source a lot of cotton from India from hand weavers and local cooperatives. There’s also like a nettle fabric that we used quite a lot in a few different productions and we’ve used it in quite a few different ways.

Hear more next time about the materials and the processes that go on behind the scenes.

This episode of Haptic and Hue was narrated and edited by me, Jo Andrews. If you go to my website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen, you will find a full script of this podcast, pictures of Emily and Alessandro and some of the costumes we have talked about, You can also find a form there to get these podcasts directly in your in-box, which gives you a chance to win some of the textile related gifts I give away with each episode.

Thanks to Alessandro Nivola and Emily Mortimer for sparing their time to think about this. When you see them on stage and screen in future I hope they have helped you understand a little more of what goes into their performances.

Thanks for listening and I will leave you this time with an inscription from the grave of John Smith, who was a clothier in Frome in the West of England. He died in 1745. It was sent to me by Carolyn Griffiths and it’s not about the kind of transformations we have been talking about in this episode but instead about the transformation from life to death and I think it expresses beautifully the connection between threads and our life force.

Frail is the vestment once I made

death has dissolved this human thread.

My frame, I thought so firm, so whole

was but a clothing for the soul.

The cloth and thread I wove and spun

by time and weather were undone;

And now the Fates which upon the chain

have cut the thread of life again.