A Dance To The Music Of Time:

The Costumes Of The Ballet Russe

Episode #40

The Ballet Russe was such a phenomenon that artists like Matisse and Picasso were happy to design for it, joining in-house artists like Leon Bakst and Natalia Goncharova. Today, over a hundred years later, very little survives of the incredible performances given across Europe, America, and Australia by the company, except for the glorious music and the wonderful costumes. These are often battered and bruised by a life on the road – they are far from pristine, stained with sweat and makeup, repaired and remade, but they have extraordinary stories to tell us, of where they were made and how they were used to change our ideas about dance and culture.

This episode of Haptic & Hue focuses on the costumes and the difference they made to our understanding of fashion and style in the early twentieth century. It also uncovers some of the unknown hands that actually made these costumes and night after night sat by the side of the stage repairing and darning, so that the show could go on.

The people you hear in this episode are:

Jane Pritchard, Curator of Dance at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Dr. Caroline Hamilton, Dance and Costume Historian. Her website can be found at https://carolinehamiltonhistorian.com/ You can follow her on Instagram at @_travellinghistorian

Jacqueline Winston Silk, Curator, Archives & Special Collections Centre, University of the Arts, London.

The book I made most use of and enjoyed, was the V&A’s Diaghilev And the Golden Age of The Ballets Russes, Edited by Jane Pritchard, which I bought on Abe Books

If you would like to explore the costumes online, three institutions have good collections: The Victoria and Albert Museum and The Dance Museum in Stockholm, these collections are both digitized and available online. The National Gallery of Australia has an excellent collection, but so far as I can see – it doesn’t appear to be digitized yet. But it has some wonderful pictures and resources from the exhibition it staged in 2011.

Jane Pritchard, Curator of Dance, V&A

Ikat costumes from Prince Igor for Polovtsian Girls c1909. After Nicolas Roerich. Courtesy of the V&A

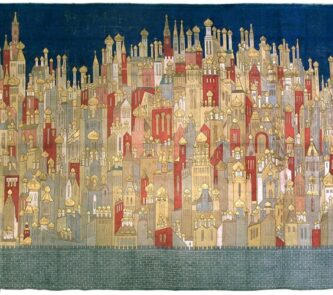

After Natalia Goncharova, Backcloth for The Firebird, 1926. Courtesy of the V&A.

Dr. Caroline Hamilton, Dance and Costume Historian

After Picasso, Costume for The Chinese Conjurer, from Parade, c1917. Picture courtesy of the V&A.

After Matisse, Mandarin Costume from Le Chant de Rossignol, 1920. Picture courtesy of the V&A.

Jacqueline Winston Silk, Curator, Archives and Special Collections Centre, University of the Arts, London.

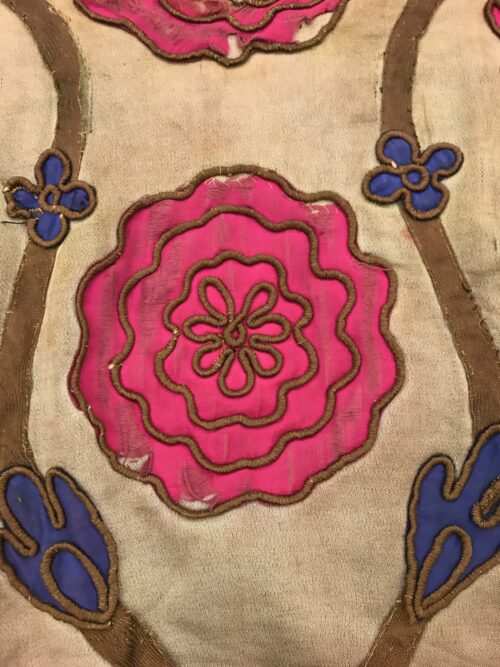

After Natalia Goncharova, Tunic for Aurora’s Wedding, the ballet opened in 1922.

Close-Up of Repeating Rose Motif and Metallic Thread

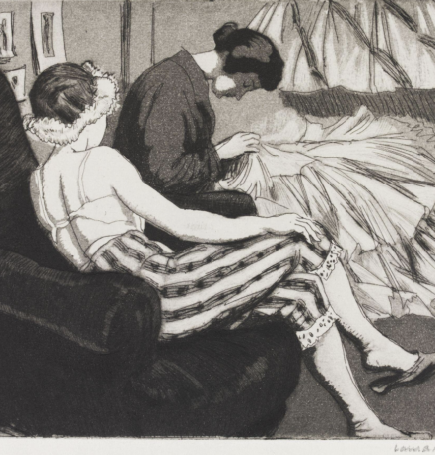

Dressing Room, 1923, by Dame Laura Knight, the dancer is Lydia Lopokova wearing part of the costume for the Ballet Russe’s Petrushka. Courtesy of the V&A

After Matisse, designed for a court lady in the ballet Le Chant de Rossignol, 1920. Picture, courtesy of the V&A.

Costume Design for the Young Rajah in Le Dieu Blue, by Leon Bakst, 1912. Picture courtesy of the V&A

After Natalia Goncharova, The Prince from Sadko, 1916. Picture courtesy of the V&A.

After Mikhail Larionov, the Buffoon’s Wife from Chout, 1921. Picture courtesy of the V&A

After Coco Chanel – costumes for The Blue Train, 1924. Courtesy of the V&A.

Script

A Dance to the Music of Time

JA: So, settle down! It may sound like an ordinary night at the theatre, but this is the story of how costume and textiles played a central role in one of the great artistic and cultural upheavals of modern times. It was a revolution that attracted artistic giants such as Picasso, Matisse, Stravinsky, and Nijinsky. But as ever, the skilled textile hands at the heart of this story have been largely forgotten until now. It’s a summer evening in Paris, June 1910, we’re at the Paris Opera House in the 9th arrondissement, waiting for the curtain to go up on a feast of costume, music, and dance. The evening we are about to enjoy will change the world of art and culture – ushering in the 20th century – and saying goodbye to the 19th. It will mark the debut of a remarkable new era of ballet with fresh music, dance, and magically innovative costumes. After this, it will be acceptable for dance itself to command our attention for an entire evening, and trace us a story in steps, music, and, of course, extraordinary textiles, rather than being part of a mixed bill of entertainment.

This is the premiere of The Firebird, with Stravinsky’s wonderful music, and Mikhail Fokine’s choreography. But for the audience, the costumes designed by Alexander Golovin and Leon Bakst and the beautiful painted backdrops reflecting the Russian origins of this folk tale would also have been astonishing. Everything about this evening was new. One Paris critic called it: “the most exquisite marvel of equilibrium that we have ever imagined between sounds, movements, and forms: a danced symphony”

That was the brilliance of the Ballets Russes brought together by the Russian impresario, Serge Diaghilev. The scores commissioned by Diaghilev shaped 20th-century music, the costumes shaped fashion, and more importantly were transferred from the stage to the street. They changed what people wore and how they decorated their homes.

Jane Pritchard: Certainly, the influence of the Ballets Russes is inestimable. I don’t think there is another performance organisation that has quite such a wide impact through, the rest of the 20th century and onwards. It’s still, actually there, which is quite extraordinary. And I think it was the fact that it really was sort of revitalizing. Ballet had become pretty moribund by the turn of the 19th century into the 20th century. It was very formulaic. And then suddenly there is this explosion of superb dancing, of interesting music, challenging music – of a wide range of designs that hadn’t been seen before.

JA: Jane Pritchard is the Curator of Dance at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. She knows that Ballet is the most fugitive of the performance arts. If you weren’t there in that theatre for that performance, with the lights, the costumes, the dancers, the smell of the makeup, and the music, it’s hard to describe the magic, and more than 100 years later no one is left who was there. But what does remain from all the wonderful performances given by legendary figures like Nijinsky, Massine, Markova, Fokine, and Lifar is the music and, amazingly, the costumes. These are extraordinary and they survive only by chance – a simple twist of fate. Jane is head of a department that cares for more of them than anywhere else in the world. These aren’t run-of-the-mill tutus and tights but works of art, designed by people like Matisse, Picasso, Coco Chanel, and others. And this episode of Haptic and Hue is about Serge Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe, its costumes, and what they tell us about the age in which they were made.

Welcome to Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles, my name is Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver, interested in what cloth tells us about ourselves and our societies. Often the stories and information that textiles can give us are ignored and we lose a whole dimension of human experience. This podcast is about trying to restore that. Jane at the V&A says that the creation of the Ballet Russe wasn’t really what Diaghilev had in mind at all:

Jane: The Ballets Russes in a way came into existence by accident, which was, sounds sort of a strange comment to make. But essentially when one looks at what was happening in the late 19th century in terms of dance, I think it had become fairly stereotyped. Russia was one place that, I think had very good training for dancers. It also devoted a lot of money. So the Imperial purse put money into it, and it was one of the few places where you would have evenings of just dance, just ballet. And you had some very long ballets. And those were works like Swan Lake, Nutcracker, and other works that people know now. And so there is an assumption that in the 19th century, everywhere was performing these sorts of long ballets. They weren’t by and large, if you were going to see ballet, it would be alongside opera.

JA: So, in Russia, there was an excellent and arduous system of training for dancers backed by the Imperial Court and a repertoire of familiar and much-loved 19th-century ballets. But America had no ballet to speak of at all. And in much of Western Europe ballet wasn’t an art in its own right, it was entertainment, music hall, and light relief:

Jane: There are a few exceptions, but they are exceptions. So, ballet did not have an independent existence in many countries, but it was popular, there’s no doubt about it. A lot of it was performed in musicals, in popular theatre, but it was, I think, fairly formulaic in the way it worked.

JA: And if the ballets were formulaic then so were the costumes:

Jane: You would’ve been looking at a hierarchical company with your ballerina who would wear a tutu. Definitely. And it was a status symbol. There are actually court cases whereby a ballerina is given a costume that is not a tutu. And so she takes the management to court: this is not what a ballerina should wear. So you have a tutu that through the 19th century got shorter as technique changed, so showing off the dancer’s legs. The costumes would reflect fashion to a certain extent, actually quite a lot of the tutus have a sort of bustle effect at the back. I mean, it’s only fairly small, but if you look at the profile, it’s there. So, I think you can see it is related to what was expected in society. A lot of the Corps de Ballet would be in probably more elaborate dresses because they wouldn’t be expected to move a great deal. And they would very often have a prop in their hand, something that sort of told you who they were. There was a lovely instance where there was an interview with Ninette de Valois who sort of said, well, of course, everyone had something in their hands. They never learned to use their upper body very much.

JA: Enter Sergei Diaghilev – a man who was the very definition of an impresario. He loved opera and art and thought he could make money and his reputation by taking Russian artists to Paris. In 1908 his summer opera tour was well received, but he lost money on it. In 1909 Diaghilev decided to repeat the experiment but to mix opera with some ballet because – and this astonished me – the ballet dancers were cheaper to take than the opera stars – and so the Ballet Russe appeared for the first time, in Paris, as part of a mixed programme. In 1910 Diaghilev returned with a new ballet, The Firebird, set to music by Stravinsky, with his star dancer, Nijinsky, and the Ballet Russe was born properly. From then on Diaghilev set about creating a company with Nijinsky, and Fokine his choreographer, Stravinksy his composer, Bakst his costume and set designer, and the Russian dancers. In 1911 it became a year-round operation based in Paris but touring London, Brussels, Berlin. As with everything else, the Ballet Russe’s approach to costume was different. They created designs like tunics that allowed the dancers to use their whole bodies and not just parts of them. They used different techniques, applique, embroidery, beading, painting, stenciling, screen printing and dying to create bold shapes and intense colours.

The Ballets Russes’ costumes begin to influence fashion and interior design as the ballet themes fed through in popular imaginations. Here’s Dr. Caroline Hamilton – a costume and dance historian who is also the daughter and the granddaughter of ballet dancers:

Caroline So at the beginning of that, it’s still very much, Edwardian clothing, we’re just moving into the teens and then obviously into the twenties. But I think this just explosion of colour must have just been quite revolutionary. And you can definitely see the impact directly in the fashion of the early teens when you get particularly French designers with sort of like the lampshade tunics with this kind of sense of turbans and hareem style pants, all that kind of look towards the East. I would say that is probably directly influenced by the Ballet Russe. Also, in interior design as well. But I think it was the use of colour, the freedom. So the fact that they were suddenly, wearing costumes more reflective of the characters, they weren’t wearing point shoes, they would be wearing, you know, bare feet you know I think that was quite revolutionary too.

JA: Jane Pritchard says for the first season the costume makers scoured street stalls for the production of Prince Igor:

Jane: They went to the markets apparently in St. Petersburg and acquired the ikat fabric which was so wonderfully colourful. I mean, gosh, that would pick up the light beautifully. And so you actually had these very, very colourful productions. So that was probably one of the most original at that point, that first season. We look at the other works, there was Cleopatra, that also had tunics, it liberated the body in terms of the style of the costumes

JA: But it was the second season when they bought Scheherazade – the Arab folk tale of the girl who tells the Sultan tales for 1001 nights that really began to influence fashion and design:

Jane: And that simply captures the popular imagination. Again, I think we have a sort of symbiosis of what is happening in fashion. So within fashion, you are really getting the sort of slightly simpler dress sort of late in the first decade. And here you get to the hareem pants, and wonderful decoration sort of coming through. So basically, there is again, costumes that liberate the body, costumes of a quality that captured the popular imagination. I mean, it was a whole production, the setting and the sort of the hareem and everything. Now, it’s not to say that some of the other earlier productions hadn’t used some of these devices, but not to the same extent, and not, I think with the same use of colour.

JA I would love to have explored the V&A’s collection of Ballets Russes costumes, but at the moment – except for a couple on display in the Theatre and Performance Gallery – all are packed away, waiting for the opening of the museum’s new archive centre next year. That meant we had to go elsewhere to see these survivors. Luckily London’s University of the Arts holds around 40 items from the Ballets – some of them dating from the earliest years – and Jacqueline Winston Silk who cares for them got out a number of them for us to look at:

Jacqueline: Well, I mean the garments are beautiful and you’ve got a mix of workmanship, so a lot of them look like they’re screen printed. You’ve obviously got some lacing, you’ve got some velvet. I mean we do know that the Ballet Russe were working with the times most influential people. Um, certainly in terms of designers, choreographers, musicians, and I assume that would extend to the people who are actually making the garments as well., but I mean certainly they’ve stood the test of time and they’ve certainly been extremely well worn. A lot of them have got staining on the inside. So it’s nice to have that more forensic look at the garments, things have been sweated in, there’s makeup on them, you know, things have been damaged. Things have been repaired. So the fact that they’ve been repaired and re-worn does suggest that, a lot went into them in the first place. Because why would you go to the effort of remaking something which you could make again?

JA: Above all these costumes were work clothes: Sarah Woodcock who writes about ballet wardrobe says they were “Redolent of the disreputable, ephemeral hurly-burly of theatre, costumes reek of life and perspiration, of the nightly stress of performance, when they were thrown on and ripped off, struggled into by other bodies than those for which they were made, then packed into skips still soaked with sweat. They bear honourable scars – hasty repairs, alongside more careful darns and patching, alterations for different dancers, the rotted fabric under arms and around belted waists, make-up ingrained into the necks.” One piece in this collection seems to sum up everything that was brilliant about the Ballets Russes and it bears its share of honourable scars.

Jacqueline: Let’s just lift the garment out. It’s actually quite heavy, heavily embroidered. The fabric is heavy. It must have been hard to dance in. So this tunic, it’s almost oversized, isn’t it? It’s this kind of outsized, oversized tunic,, very heavily embroidered and not, not screen printed this time, but almost using applique.

Jo: So what we’ve got is sort of, it’s difficult to tell what colour it would’ve been, but um, I guess a sort of brown or beige background and then appliqued onto that.

Jacqueline: Yeah, these kinds of roses or sort of rosette floral motifs.

Jo::With again, there’s beautiful bright pink and then rather lovely violet offsetting smaller pieces. And then it almost looks like frogging. Um, but it isn’t really, it’s the most fantastic stitching in really wonderful designs. I can’t imagine anything more different than a sort of classical 19th-century ballerina’s tutu.

Jacqueline: Well, no, I mean that it’s so far removed, isn’t it? But that, I suppose that in itself is, is the whole notion of the Ballet Russe. They were creating original performances. They weren’t necessarily rehashing existing ballet stories, they were producing performances that were unlike really any ballet that had come before them. And I think that legacy plays out even now. And even this has got this lovely, I don’t know what you’d call this, this almost additional kind of piece of material that no, it’s almost just adding in material for the sake of movement, I think.

Jo: And it’s right down the side.

Jacqueline: Yeah, A flap of material. It’s like a flank, isn’t it? Almost.

Jo: That runs from under the arms way down the hem. And this would’ve come what? Just onto the thighs of the dancer?

Jacqueline: Yeah, I think if my memory serves me correctly, I think in the image the dancer is, it’s a male dancer, and then underneath he’s just wearing tights. So a sort of long, long-ish tunic that would’ve gone, I suppose below or sort of halfway down the thigh potentially. But again here, lots of signs of repair here. So you’ve got, well there’s a very large repair in what would’ve been, I suppose, the armpit of, of this garment. And it almost looks as if, if we compare it to the other side. Oh no, there is, it’s almost the same on the other side. But you can see there’s this, I suppose, webbing that’s been applied on the top. And that’s completely threadbare. And you can see traces of repair in, the green thread. It’s almost quite difficult to distinguish repair from design in some of the places. But you can see here there’s a tear in the actual fabric and that’s been worked and repaired. Look on the other side again, you can see the areas that would’ve been under the most stress here on the back of the shoulder. You’ve got this repair. So you can see they’re real working garments.

Jo: And the repairs in a sense are quite minimal, aren’t they? It’s just to allow you to get up and perform again.

Jacqueline: Yeah, they’re quite quick. You’ve just got these very basic stitches. I think they’re just perhaps at the side of the stage, a seamstress, you know, fixing the garments ready to go back on stage doesn’t look like a great amount of care has been taken with the repairs.

Jo: And, again, this is fantastically heavy.

Jacqueline: Isn’t it? This is very heavy. I mean, not all of them are heavy, but I suppose if you are only dancing in this and a pair of tights, that’s not too bad. <laugh>, maybe the slightly more restrictive garments might be more difficult. It is heavy, but I think that just comes down to the level of detail that you’ve got onto it that’s been applied.

Jo: You must have got quite hot in it though, I think.

Jacqueline: Yeah, the makeup, the sweat. Absolutely. You’ve got, I mean, there’s, there’s staining all over the place, but I think it, it adds to it and it’s, it’s the kind of excitement of being on the stage, isn’t it? Who knows what these garments have been through?

JA: And the knowledge of what these garments have been through has a profound impact on the way Jacqueline approaches her work in caring for the costumes.

Jacqueline: Yes, you see these stains and repairs and you might perhaps think initially they make the garment look unsightly. But on the contrary, I think all of these marks this kind of patina builds up the object’s story. So if we were to remove that, you would be removing the history, the essence, the significance of the object. And I think embracing these marks or holes, rip stains, whatever they may be if they’re contemporary with the object. And I think that it’s, that enriches our understanding Absolutely, of what the object is. And to remove them would just completely change the object. And I don’t think you’d ever actually be able to remove them. I think if you were to try and clean something like this, you’d be setting yourself up for a failure. <laugh>.

JA: Diaghilev being Diaghilev wanted the best in terms of designers for his productions and his costumes. He believed in perfection. Each dancer was checked before going on stage and fined for any changes to the costume and makeup, or for wearing unsuitable jewellery. And perfection extended to his designers. In Paris he persuaded Jean Cocteau to work for him, then Picasso and André Derain, and after the First World War he invited Henri Matisse to design the set and costumes for the ballet called Le Chant de Rossignol.

Jane: With the Matisse, we believe with the costumes that Matisse probably did the painting on them. So they really are the work of the artist. It’s, interesting because different designers, artists, designers, some of them are much more interested in the set, which one can understand, which I think probably was the case with Picasso, So, that, you can sort of see. But he was hands-on painting the set. He wasn’t, as far as we know, hands-on in the way Derain was everywhere. He was very involved with everything. So, he would’ve kept an eye on what was happening with the costumes being made. I’m sure Matisse became far more interested in the costumes than in the set. And he went to the atelier and was there sort of, and the brush strokes are so loose on the decoration that, it’s not like someone’s got a stencil to do it. You can see they’ve basically been painted on. So, it is believed that he probably painted at least some of the costumes themselves. So, handling them is, I mean, it’s quite amazing actually.

JA: Stage costumes are not couture, they do look tawdry and tattered close up, it’s how they move when there’s a dancer inside them and what they look like under lights that matters. Making ballet and theatre costumes is a very different skill from dressmaking. This is not about the long term, instead, makers work towards the opening night and the hope that the run will be a success. Costumiers need to be able to translate a drawing into a finished garment, understand how to make a design work at a distance and construct them so that they are resilient enough to survive the dance itself and the process of touring. And this brings me to a question – one that I think is vital. We have heard an array of famous names in this episode, the Ballets Russes played a part in helping these people build their reputations, but in most cases, their hands were not those that actually made these costumes. The dancers were famous, the designers were famous, and even the costumes are now famous, but who were the makers? Here’s Caroline Hamilton, who among many other talents has been a dresser at Sadlers Wells in London and a costume maker for the National Ballet of Canada.

Caroline: That’s sort of what kind of took me down the rabbit hole of really looking at the construction of these costumes is because the makers often aren’t recorded. And that is something that a lot of research is going into now. The Victoria & Albert Museum has been really good about trying to find out who actually made these pieces, the same with the National Gallery of Australia. But we still don’t know who made all of these costumes. We know who designed them. And I think that’s a key difference here is costumes had not been designed like this before. They were employing artists not theatrical designers. So, they were coming up with these incredible, fantastical designs. If you’ve ever looked at one of Bakst’s designs for the early Ballets Russes they were beautiful pieces of art, now how do you turn that into a costume <laugh> And I think that’s where the real skill is, because that’s where these, often women, were turning that drawing, that beautiful rendering, into an actual garment that could be danced in, but also still had all the elements of the design. And it was also their responsibility to design the back because nearly always the designers only drew the front <laugh>. So, I think that’s such an interesting sort of dialogue there.

JA: The Ballet Russe didn’t have a wardrobe department – it wasn’t that kind of company – it was a ballet in exile and essentially it was always on tour

Caroline: They travelled with you know, sort of a maintenance, so, people that would look after the costumes, dressers, and a head of wardrobe in that respect. But they didn’t have a costume shop. So, a lot of the costumes were made in Paris, a lot in London and just wherever they were, and in some cases, you know, with varying skill. So, you get something like Sleeping Beauty, which was a huge ballet and there were multiple makers. I think there are at least five different makers and sometimes you get a set of couples’ costumes for instance. And the women’s costume was by one maker and the men’s costume was made by another. And although they go together and they look very beautiful from a distance, up close you can see that the female’s costume in this example is beautifully made. And the other costume, the man’s costume, is really rough <laugh> and you know, bits are just painted on because they didn’t have time to make all the detail. And I love that because that just gives so much more information and it also gives you information that isn’t available from any other source.

JA: Caroline says the Ballet did build relationships with certain makers at different periods.

Caroline: So one of the most prominent makers was Madam Muelle, Marie Muelle. And she was an opera costumier in Paris. She had her own atelier and she made nearly all the costumes for Bakst’s ballets. They seem to have formed this kind of relationship around 1911, 1912. And from then on, she and her workshop made all his ballets and made quite a lot of the costumes for Sleeping Princess as well. They just seemed to have had a really good relationship and she could make his designs a reality in a way that he was happy with and Diaghilev was happy with. In the first few years of the Ballet Russe, the costumes, a lot of them were still being made in Russia and being brought out. And then as they were permanently based in Europe, more were made in Paris, in London, etcetera They used companies like Morris Angel, which we know now as Angels, the big costume workshop and warehouse, which is still going today in London. They provided some in London. Yes, they provided some costumes when the company was there in the late teens, and sometimes, you know they would lose costumes, they would need additions made or, you know, designers would change the style of the principal costume, for instance, and things would need to be altered quite quickly.

JA: And she says that she can tell by looking at the stitching and the way in which a garment is constructed what period it comes from.

Caroline: Yes, absolutely <laugh>. I mean, it’s still definitely a little bit of sort of, you know, guesswork, but I’d say particularly someone like Mme. Muelle’s work is quite distinctive. The attention to detail is just incredible. A lot of really, really precise appliqué, beautiful use of colour and really, you know, no expense spared in the fabrics, in the trim, also in the detail when you think a lot of this is, all being hand done at this time and later on you get, use of embroidery machines and things like that, but early on it is not. And that is just really quite amazing. And then yes, you get costumes that are much more roughly made and then you can sort of hazard a guess about, around about when based on some of the other pieces as well.

JA: At the V&A they hold a number of costume receipts so they can follow the trail of costume makers around Europe, even if the actual hands – the petit mains – as the French call them, often remain unknown. They know that Stravinsky’s wife, Vera, made some of them and also that Coco Chanel began to design for the Ballet: here’s Jane:

Jane: So, Chanel for example, is very involved with the company in the 1920s. She begins actually, actually as a sponsor putting money into the company for the revival of the Rite of Spring. So, when Massine does the second staging of it she’s apparently behind that. Obviously very involved with Stravinsky at the time. But then she becomes an advisor to Diaghilev about the costumes and things like that and goes on and actually designs. And obviously, her Atelier is behind the making of the costumes for the Train Bleu, the Blue Train, which is a ballet about sport. So, you’ve got the tennis player, you’ve got the bathers you know, and the golf player? The golf player is sort of based around the appearance of the Prince of Wales. The tennis player is inspired by Suzanne Lenglen who was a great tennis player at the time.

JA: Part of Caroline’s job is to assess where and when a costume might have been made – acting as a kind of textile detective – and one of the first things she does is to look inside a costume – that’s where the information is.

Caroline: When you look inside some of these Ballets Russes pieces, you know, there are lists of literally names inside, you know, of all the different dancers that would’ve worn it because for dance ballet, you know, a new costume isn’t made for every cast every time the ballet is revived, it’s the same costumes. And that still is what happens with ballet companies today. You know, it’s very expensive to make these costumes. So, they will be worn for 20 years, sometimes even 30 years, by successive waves of dancers and they will be altered to fit them. But if you’ve ever been sort of close to the stage of more of a sort of tutu ballet, for instance, Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, something like that, and if you catch a glimpse of the back of the costumes, you might notice multiple rows of hooks and bars. And that is so because the next night that tutu might need to be on a different dancer and needs to fit that dancer as well. Wow. so yes, when you are in the audience and you are looking at them they still look wonderful under the lights, with that distance and up close, you know, they can look super scruffy, but that is part of the history, and part of their life as a working object.

JA: And this is what gives these costumes their power and emotional force. They may not look pristine but they hold the memory within their threads of skill and artistic endeavour – they whisper of opening nights, stage fright, and tumultuous applause – they are scented with exertion and curtain calls. Diaghilev died in 1929, but his companies lived on in various forms for many years and finally collapsed in the 1950s. The costumes went into storage outside Paris and were forgotten until the 1960s when interest in the Ballets was revived. In the late 60s and early 70s, three grand auctions of the sets and costumes were held in London. Many of them eventually came to V&A. The Museum of Dance in Stockholm also successfully bid for a number of the costumes and famously at the last auction nearly a quarter of the items went to 11-year-old Andrew Strauss, guided by his father, who was bidding on behalf of the newly established National Gallery of Australia. And now 100 years later it is the costumes more than anything else that have become the stars of the show in their own right, taking us both back to the past but also acting as inspiration to future generations of dancers and designers, reminding us of the need for renewal and innovation in all artistic forms

Thank you for listening to this episode of Haptic and Hue, and I owe a great deal of thanks to Jane Pritchard of the V&A, Costume and Dance Historian, and to Dr Caroline Hamilton, and Jacqueline Winston Silk, of the University of the Arts. If you would like to see pictures of some of the costumes or read a full script of this podcast, you can find them all on Haptic and Hue’s website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews, and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a member of the new Friends of Haptic & Hue, which costs £50 a year or £5 a month. This keeps the podcast truly independent and free from sponsorship and advertising and brings you extra content every month. If you’d like to find out more, it’s on the website at www.hapticandhue.com/friends.

To end this time, I want to remember all the unknown and largely female hands that worked on these costumes – that translated the designs of all the artists into practical costumes that could be danced in and looked wonderful under the lights, and who sat night after night at the side of the stage and repaired and darned so that the show could go on. Here is an unusual extract from Rimsky Korsakov’s ballet Sheherazade played on guitar.