The People’s Art

Material and the Modern Masters

Episode #42

This tells the story of how fresh and fashionable art-textiles were among the first items people were able to enjoy in the peace that followed the Second World War. It focuses on a short period of production, in America, when manufacturers turned to established artists, like Picasso, Raoul Dufy, Marc Chagall, and Miro, to help them create technically sophisticated and beautiful new textiles. It looks in particular at Daniel B. Fuller’s attempt to create what he called “A Museum Without Walls’ with his Modern Masters series of textiles in the 1950s.

It also tells the story of a young artist, unknown at the time, called Andy Warhol, who worked for these same textile producers as a pattern designer, and used his experience and skills to change the face of twentieth-century art. Until recently his textile designs have been lost – listen to how they were rediscovered and the painstaking process of proving that Warhol had designed them.

The people you hear in this episode are:

Leigh Wishner, design historian and expert in American patterned fabrics. Look out for the book she is currently writing on 20th-century textiles. She is a fund of interesting information. Follow her on Instagram @patternplayusa

Dennis Nothdruft, Head of Exhibitions at the Fashion and Textile Museum in London. The Museum has a rotating series of exhibitions and workshops that are always worth checking out. You can follow them on Instagram @fashiontextilemuseum

Richard Chamberlain and Geoff Rayner founded the Target Gallery in London which has led the way in sourcing and curating artists’ textiles. www.targetgalleryuk.com .

Matt Wrbican: Richard and Geoff want to acknowledge the help and support they received from Matt Wrbican, who was the Chief Archivist at the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, who sadly died during their research.

If you want to find out more: Richard and Geoff are the authors of the main books on artists’ textiles – which are in the Haptic & Hue US and UK Bookshops:

Artists’ Textiles by Geoff Rayner and Richard Chamberlain UK

Sadly, this doesn’t appear to have been published in the US – but you may be able to get it second-hand on www.bookfinder.com

Warhol: The Textiles, By Geoff Rayner and Richard Chamberlain UK

Warhol: The Textiles, Geoffrey Rayner and Richard Chamberlain US

The V&A’s collection of the Modern Masters fabrics can be seen at https://collections.vam.ac.uk/context/organisation/A19202/fuller-fabrics

Leigh Wishner

Life Magazine November, 1955

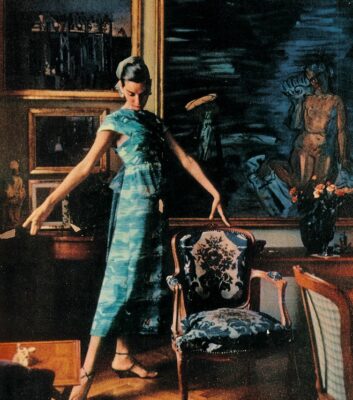

Model in Raoul Dufy’s Studio for Life Magazine, 1955

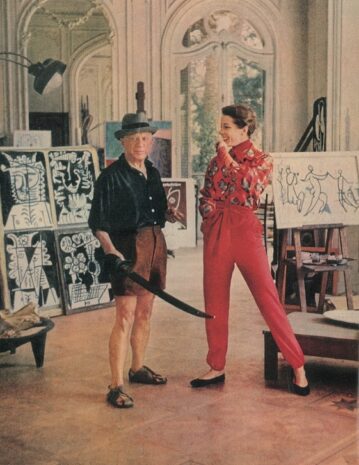

Picasso and Model for Life Magazine, 1955

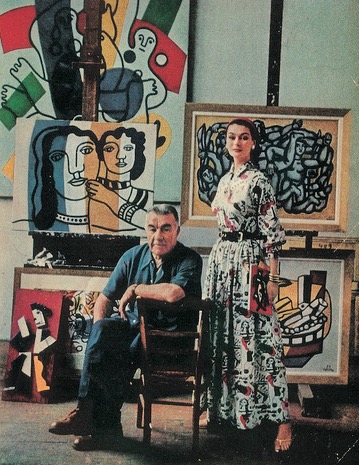

Ferdinand Leger and Model for Life Magazine, 1955

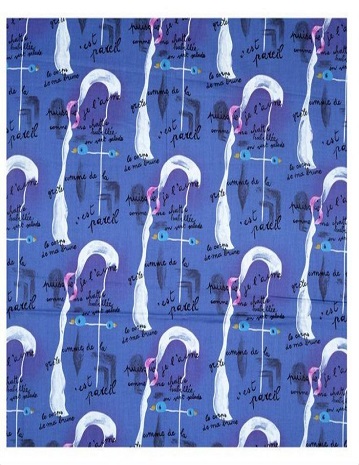

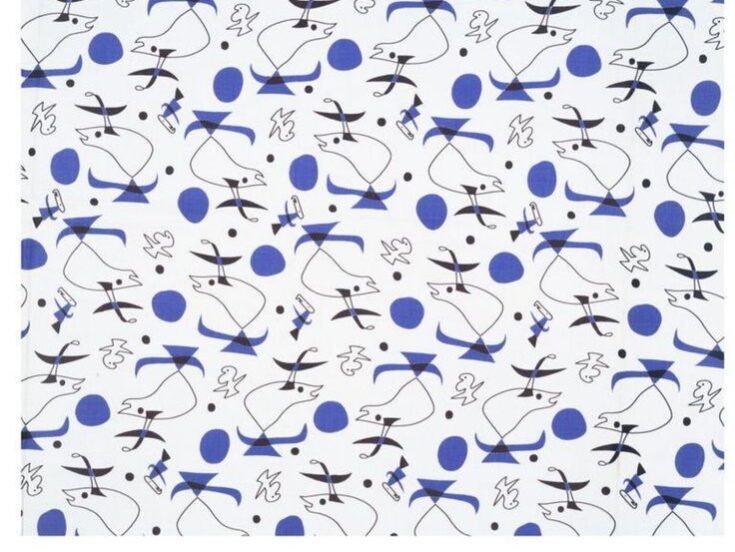

Joan Miro – Peinture Poeme, Fuller Fabrics, Modern Masters, 1956. Picture Courtesy of the V&A Museum.

Joan Miro – People and Birds, Fuller Fabrics, Modern Masters, 1956. Picture Courtesy of the V&A Museum.

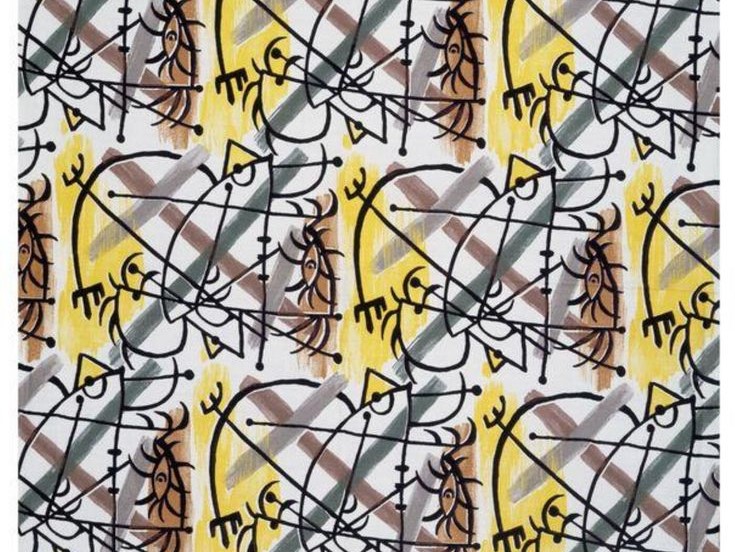

Pablo Picasso, Length, Fuller Fabrics, Modern Masters, 1956.

Picture Courtesy of the V&A Museum.

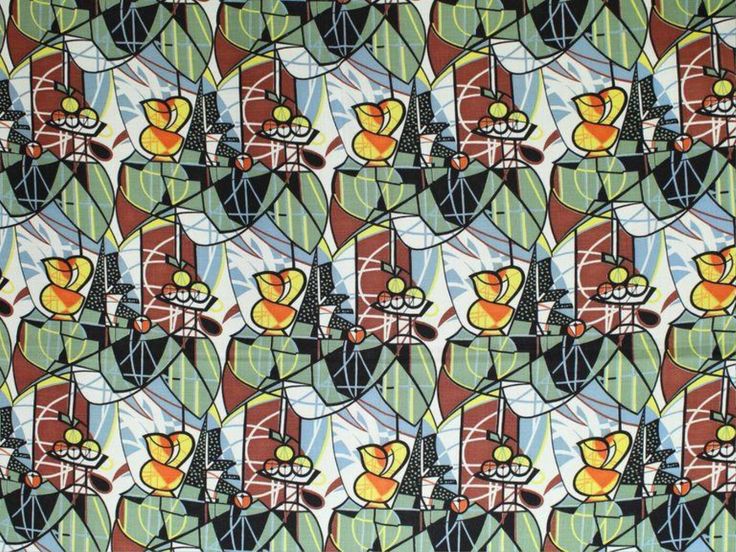

Pablo Picasso – Pitcher and Bowl of Fruit, Fuller Fabrics, Modern Masters, 1956. Picture Courtesy of the V&A Museum.

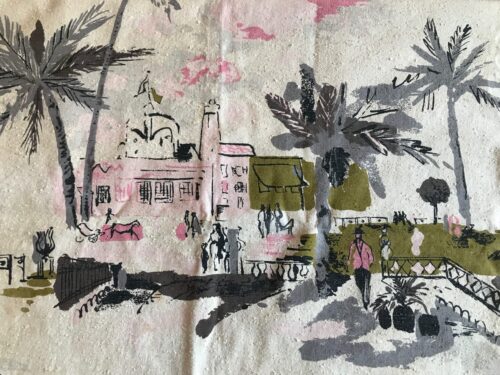

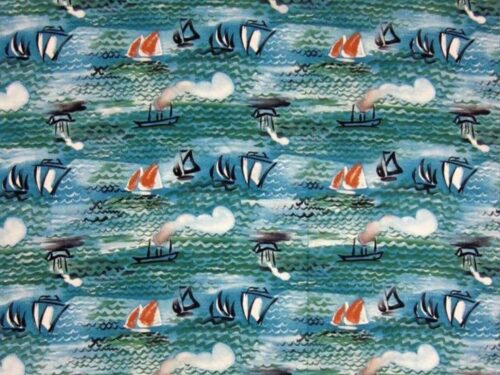

Raoul Dufy – Fabric ‘Cannes’ for Fuller Fabrics, 1955

Raoul Dufy – Le Havre, Fuller Fabrics, Modern Masters, 1956.

Picture Courtesy of the V&A Museum.

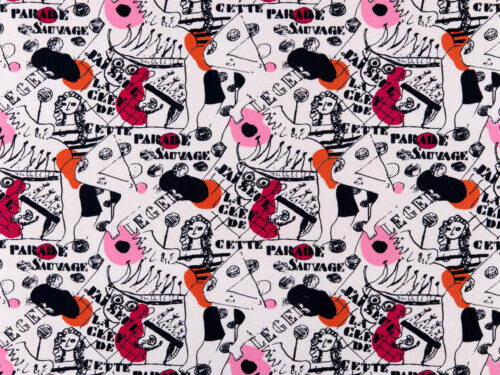

Fernand Léger – Parade Sauvage, Fuller Fabrics Modern Masters, 1955. Picture Courtesy of Gray MCA

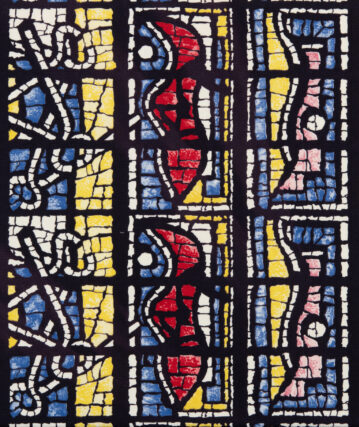

Fernand Léger – Vitrail, Fuller Fabrics Modern Masters, 1955. Picture Courtesy of Gray MCA

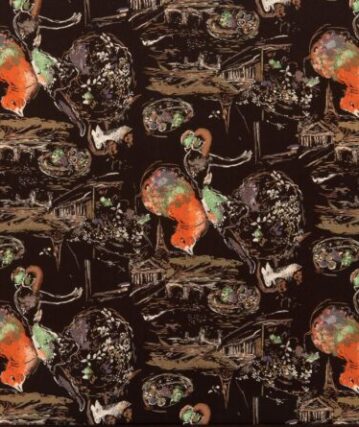

Marc Chagall – Les Amoureux, Fuller Fabrics Modern Masters, 1956.

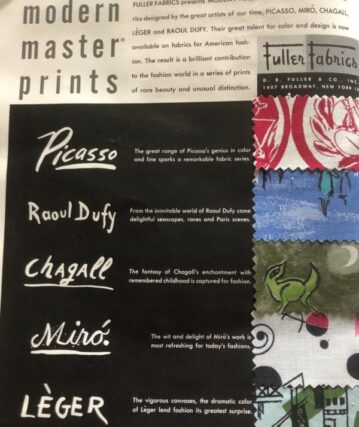

Fuller Fabrics’ advertisement for its Modern Masters fabrics

Richard Chamberlain and Geoff Rayner

Skirt in Flag Design – Andy Warhol Design

Toffee Apple Dress – Andy Warhol Design

Pretzels Dress – Andry Warhol Design

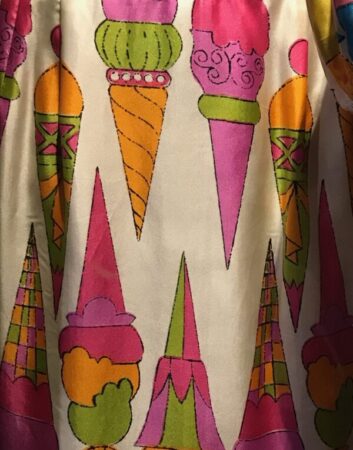

Ice Cream Cone Fabric – Andy Warhol Design

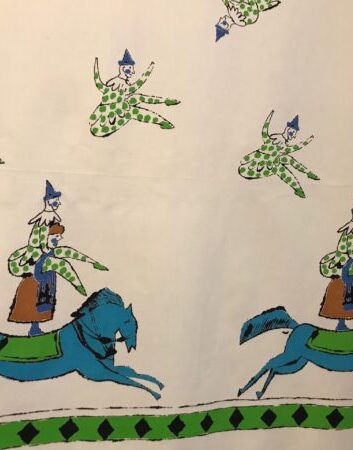

Tumbling Clowns – Andy Warhol Design

Happy Day Bugs – Andry Warhol Design

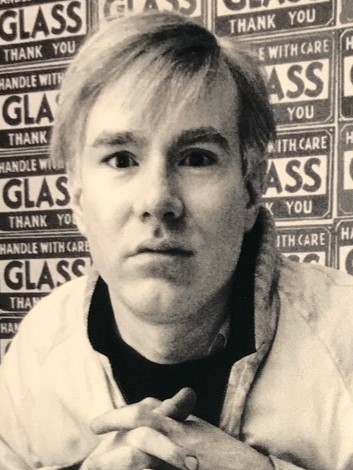

Andy Warhol at the time of his brief textile designing career

Dennis Nothdruft

Script

The People’s Art – Material and the Modern Masters

JA: There’s a lovely thought from that most magical of weavers, Anni Albers, who said of weaving that “like any craft it may end up producing useful objects, or it may rise to the level of art.” The boundary between craft and art is an interesting one, because its disputed territory, and the border changes all the time. The traditional question is when does craft become art? But let’s turn that around and ask what impact textiles have had on fine art and what happens when famous artists like Picasso, Dufy, Miro and Chagall lend their art to textiles. Does this then become fine art or does it remain textile design?

Leigh Wishner: I love this question because they are both, but I would never call them art. I believe fabric design is an art in itself, and that not everybody can do it. you can’t lose sight of the fact that every fabric in the Modern Masters line was made as a commodity, there’s a lot of advertising or a lot of promotional that shows a piece of the fabric in a frame on the wall. You can do that, absolutely. But it was never the intention. The intention was for this product to be used. Artworks are not defined in relationship to use. They are standalone things that don’t have to have a purpose. But the fabric was created as yard goods for a purpose. The art exists to express ideas, and the ideas that are being expressed by the Modern Masters Project are definitely about taste in art and accessibility to the art. But it’s, but it’s underscored entirely by consumerism.

JA: That’s Leigh Wishner – a design historian and an expert in American fabrics. Welcome back to this edition of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. It comes after a summer break which we spent on the streets of Edinburgh and the beaches of Northern Scotland – the results of which will turn up in podcasts to come! But this episode is about artists and textiles. My name is Jo Andrews, I’m a handweaver interested in what cloth says about ourselves and our societies. This episode focuses on a particular period in America when a number of renowned artists became involved in textile design resulting in a line of fabrics called Modern Masters Prints. But it’s also about a young, unknown fabric designer who was working at much the same time, often for the same companies, who took the discipline of textile design and pattern repetition and used it to change the face of late 20th century art.

Dennis Nothdruft: I think one of the strong points, one of the things that really stands out for me is this use of repetition. And I think Andy Warhol as a fine artist, exploits this idea of repetition very, very successfully. And these were things that he had used in his commercial illustrations and in his textiles. And that’s the same idea that he explores with his silk screen. So, if you look at 360 Marilyns you can see that, the image is degrading as he’s printing more and more and this, the ink runs out or there’s a blotch. So, you get this amazing sort of sense of movement through all of those Marilyns and you get that similar idea through his work as a textile designer.

JA: Dennis Nothdruft is the Head of Exhibitions at the Fashion and Textile Museum in London where an exhibition about Andy Warhol and his lost textile designs from the late 1950s and very early 1960s, have shed new light on his work as a fine artist. But this story starts in the late 1940s in America – the war is over and people’s thoughts are turning to peace:

Leigh Wishner: Towards the end of World War 2 and in the post-war period, the American art market in particular was sort of experiencing this incredible boom. Auction sales, or starting to reach the record highs that we, well, maybe not the record highs we see today, but in their time, they were reaching all these highs. Galleries were popping up, and gallery purchases were also surging. Wartime shortages of consumer goods, they had led to a surplus of money in the pockets of average Americans, or maybe not average, but upper middle-class Americans. And that translated a lot into increased spending on luxury goods, including art. And so that, if you backtrack even a little more the public art programs of the 1930s in this country, they definitely increased the aesthetic awareness and appreciation for art, it was sort of demystified, like, not only for just the rich people, you could even get art in department stores actually.

JA There was also a strong demand for new clothes, something bright and different after the war years.

Leigh: On the parallel track, the fashion consumption in the United States was also on the upswing. And there was a really robust demand for resort and sportswear, junior apparel what they called and we call still play clothes. And they just reflected a different modern, casual lifestyle. And, you know, it’s really interesting that just artists and galleries and, and textile companies started to all kind of put this together at the same time that they, they, these, the trends and the entities work together to create a desire for this in the marketplace.

JA: There was a hunger too for things European, America had been cut off from European style and savoir faire for many years. The American market was a strongly competitive one with lots of manufacturers all looking to differentiate themselves from the next company. And to give themselves a bit of cachet and exclusivity some companies like Laverne Originals. Lowenstein and Sons and Milton Schiffer started asking artists for designs that could be sold as artists prints. Often, but not always, these were American artists. Then in 1953 Daniel B Fuller of Fuller Fabrics decided to create a line of artists’ fabrics that featured the greatest names of the day.

Leigh: Well Dan Fuller approached Picasso through a mutual friend. And, you know, I think a lot of people nowadays would think that no fine artist would, would wanna work in a medium like fabric design. It’s tainted with commerce, right. <Laugh> though he was, he was hailed in his day, in that moment in time, they were reporting on him as the highest paid and most individualistic artist of his era. He’d been known to turn down invitations to do such projects, but because Fuller was able to guarantee a high level of fidelity to any artwork selected for the finished product Picasso decided that he would accept the challenge. And I will say that that <laugh> that opened the floodgates for Picasso and Fabrics, but that’s another, that’s another story altogether, <laugh>. But yeah, so once, once he was on board, he just kind of reached out to his friends, Miro, Chagall and Leger, and they were all enthusiastic about joining in on the project.

JA: There was by this time something of a history of artists crossing over to a textile format. The Ballets Russes had collaborated with many artists including Picasso and Matisse, Dufy had had designs block printed as early as 1912. And after all what is an artist’s canvas but a piece of fabric? But this kind of mass-produced fabric was new, and maybe after the War the artists needed the money – maybe they fell under Picasso’s spell or maybe the ethos of the project just charmed them.

Leigh: They were famous and they were, I’m sure, comfortable as artists, but the auction values never reflect what actually goes into an artist’s pocket. So, I’m sure that they were handsomely compensated for the project by Fuller, but I don’t think they thought I’ll make a lot of money on this. They were definitely enthusiastic about it, and I think that they, delighted in the idea of, of giving this democratic affordable entree into art connoisseurship. I think that it was more than a novelty just to have the ability for somebody who admires their work, but can’t afford a print or a painting even to, to wear their artwork and make life a museum without walls that’s a quote that always sticks with me. That was part of the ethos of the whole project, is that they’re trying to erode the boundaries between art, art appreciation and access and, and the average person.

JA: Whatever it was, Mr Fuller got his artists and his line of fabrics:

Film clip: ”I’m Daniel Fuller, President of Fuller Fabrics, in recent years, we have all been aware of the tremendous impact the work of modern artists has had on the design of everything we use. More than a year ago, we at Fuller’s decided to go for ideas directly to the artists who have been sources of new design in our time. We chose, Miro, Leger, Dufy, Chagall and Picasso as five artists who have made outstanding individual contributions to the thinking of contemporary designers.”

JA: And Fuller committed his company both to the artists and to the quality of the product going to extraordinary lengths to get it right – nothing quite like this had been seen before in American textile production:

Leigh: The artworks that were chosen, they were sort of selected to represent different milestones in each of the artists’ careers. So Fuller would have a design team aid the artists in selecting the right motifs that would translate into the repeat format, which was very, very compact because it is a roller printing process. The rollers themselves took more than a year to engrave. Which is kind of astounding, because, you know, Picasso would only sign on if he felt like you’re going to reproduce my artwork with exactitude. It’s true. The printing really captures like different textures and nuances of paints and glazes and pastels. Even stained glass, Léger has a really famous stained-glass pattern. They’re very faithful. And I’ve done a lot of the, the homework on matching the source material with the fabrics. And you can really see that they, they definitely hued right to the source, even in when they just strayed from the original colours of the pattern to create additional colourways. There was, there’s still something you can see. And it, it does have a quality that really does, the way that they capture the spirit of the artists really sets the collection apart from the imitators. Because believe me, there were plenty of Picasso-esque and Miro-esque patterns on the market. And a lot of people will send me something like, is this one of them? Is this one of them? And usually I have to say, I don’t think so because the quality just doesn’t look right. You know, if you actually looked at a Miro and looked at that, you’d say, eh, it’s an imitator. But when you look at a Miro from this line, you, you definitely don’t get the sense that it’s an imitation. And I think that that also is a credit to the Fuller Fabric in-house design team. Yeah. Because they had to collaborate. And, and can you imagine the pressure of like collaborating with Picasso and being like, hi, do you like this? Is this okay, <laugh>? Do you approve this artwork and have him come back with a lot of, you know, notes.

JA: So the artwork that the design team started with, belonged to the artist, but the skill and craft of turning that into a pattern that repeated successfully on a piece of fabric, that was down to the design team at Fuller Fabrics.

Leigh: They had to look at this artwork, whatever it was, and either they would pluck a single motif out of that artwork and recompose it into a textile repeat. Sometimes the entire artwork was the full motif, and then they would have to get blended into some sort of a repeat. But basically what <laugh>, even though the Fuller Fabrics promotions and selvedges, they centre the artist as the creators. I think that the key element that’s missing is <laugh> to design the repeat. That is it. You need somebody to help you with that. If you don’t think that way already, and you’re not trained to think like, I need to crank out a continuous Picasso off of this wall, then you don’t think that way. You need somebody who understands the mechanics of making that artwork translate and then not look clunky. Where do I shift this? How do I put this in a half drop? Well, you know, to make all those pieces come together as something that’s actually successful. And most of them were very successful.

JA: One of the things I love about these art textiles is that you get this marriage of skills – there is not just the artist’s vision and style, there is also the craft of the textile designers in pulling out the motifs, scaling them, designing the colours and ensuring that everything is faithfully reproduced, and If they are successful their hands are invisible.

Leigh: Yes, it takes an incredible amount of work, just from inspiration to printed, finished product. There are so many people involved and so many steps and so many approvals and yeah. And right down to copywriting them. So, it was a, a very deliberate effort that they obviously took the time to get a hundred percent right. And so, I can’t imagine that many projects being developed for that long without coming to market. So it’s really a great moment in, in American fabric history.

JA: And it was a successful moment too. The fabrics with the name of the artist on the selvedge went on sale in 1955 at between a dollar forty-nine and a dollar ninety-eight a yard. In today’s money that’s between $17 and $22 a yard. A second batch was commissioned including the artists Paul Klee and Georges Braque – and in the end there were over 60 different designs and colourways.

They sold well, the fashion houses bought them and made up their own lines, Life Magazine featured models wearing garments made by Claire McCardell from the fabrics alongside the artists in their studios in France. People loved their Picasso dresses, their Miro resort-wear, there were children’s clothes, men’s sportswear, Georges Braque covered sofas and Chagall curtains. Elsa Schiaparelli even used the prints to design swimwear. They caught the mood of the day.

Fuller Fabrics was what was called a textile converter, the company made cloth and then sold it to department stores or fashion houses. It didn’t sell directly to the public. Usually a company would advertise their fabrics to the fashion and fabric industry, but in this case Daniel Fuller had other ideas. Yes, he wanted to sell this fabric he had spent so much time and work on, but he really did see these textiles as art, committed to his idea of these fabrics contributing to life as a museum without walls.

Leigh: Absolutely. And Fuller was very conscious about this. There was a traveling exhibition of these textiles, and it hit several different institutions but most notably the Brooklyn Museum, where there was a whole, almost an educational display about how they were made, the process, some great photographs. Fuller was very conscious of promoting it within the museum context, like very calculated. That’s, that’s why several institutions have excellent collections of Fuller Fabrics. Actually, in the period he decided that there should be, these, these pieces should be in museums. Fuller made donations to three institutions each having to do with design, history and education. The Cooper Hewitt Museum, the Berea College Art Gallery in Kentucky, of all places, and the Victoria and Albert Museum, which I know you’re familiar with, they received 42 one-yard lengths in total, at the request of the curator there actually. And many of the designs are in two different colourways. And so, they are actually represented in at least the two premier design institutions in the world, as far as I’m concerned, the Cooper Hewitt and Victoria and Albert. And now subsequently to that, I will say that Lacma, Los Angeles County Museum of Art also has several designs in their holdings, which I helped place there when I worked for Titi Halle at Cora Ginsburg.

JA: Seventy years on these prints are highly collectable. They sell for thousands of dollars and sometimes are offered for tens of thousands – far more than they retailed for when they were first made. And Leigh believes that the designs have stood the test of time.

Leigh: I think they’ve dated incredibly well, actually, as well as the modern art from that period dates, it still looks fresh to us in many ways, but I do think that to say they’re timeless is not the right approach, they speak specifically to that, that post-war American moment. But I still think that because we have a very current appetite for the modern masters still in, in our own century, we still look to Picasso and Miro and, and they still pace set in the market in ways that are surprising. When people discover them today, the fabrics, the Fuller Fabrics project, they’re always enthusiastic and appreciative and, they always marvel that these big names would work in such a commercial medium. So that is still, a constant, and they’re still very, very sought after in the vintage community and, and definitely by museums.

JA: Leigh says there is still a mystery out there. The paper designs, the letters, the rollers engraved with the work of Picasso and the other artists, the artists proofs, the production details, all are lost. Fuller Fabrics was eventually bought by another company and no-one has been able to find any trace of these items. So, if one day you are clearing out an attic or a basement or you see something at a yard sale that looks like a Miro or a Klee, or maybe a Braque or a Chagall, it might just be one!

These artists were already well known when they lent their names and their designs to Fuller Fabrics to create the Modern Masters line – but at much the same time that the American public was enjoying the designs of these incredibly famous men, something in a sense much more interesting was happening under the radar. A young artist was using textiles and textile design in a very different way. He was not at the height of his career, a well-known name on the selvedge who could sell yards and yards of fabric – but he was at the start, and his understanding of the discipline of textile design was to have a huge impact not just on his work, but on the global art world in the second half of the twentieth century:

For years it has been well known that Andy Warhol started as a commercial designer, but it has been an incredible textile detective story to show that Warhol was also a prolific and talented fabric designer. The two sleuths who have dug out the wonderful story of the lost textiles of Andy Warhol are Geoff Rayner and Richard Chamberlain. They had seen lots of textiles by different artists but they just had a hunch that there might more out there – here’s Richard:

Richard: But there was one man conspicuous, or one person conspicuous by their absence, and that was Warhol. And we had no idea if he had designed any textiles then. So we approached, well, firstly, the foundation, the Warhol Foundation, who put us immediately in contact with the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, and a very helpful person to us, we met up with Matt Wrbican, who was the Chief Archivist there, and he really couldn’t tell us if Warhol had done a lot of war textile work at all. But he, he was able to point us in the direction of a particular book, which accompanied an exhibition called The Warhol Look from the nineties, I think it is. And in it are two images of dresses, dresses by Stephen Bruce for Serendipity Three. And these were using Warhol textiles, silk textiles. So that’s where it began, really.

JA: So now they knew there were at least some Warhol textiles, Richard and Geoff who are specialist researchers and acquirers of art textiles for museums and collectors, started the hunt for more.

Richard: So, we’re talking about online auctions, we’re talking about vintage clothing stores, et cetera, et cetera. But we are talking, you know, Canada, New Mexico, wherever. But it did involve a real labour of love, a dedication, really. So, a regular daily sweep or, or survey of what had come up on the internet in all of those type of venues overnight. And of course, America gets online later than we do, so we’d have to look, you know, later at night as well. Mm-Hmm. <Affirmative>. And it did start to bear some potential fruit. We found a few textiles, a handful of textiles, in fact, one or two originally, over a number of years. But I think the first one that really cemented things was the ice cream desserts one. So yeah, it just, it just grew. And of course, the internet became the primary source of finding out further information, possible links to other people that might have been involved in the textile world companies. But of course, American companies, lots of New York textile firms, a lot of their archives have been junked. They’ve been amalgamated with other firms that’ve been taken over, or they just went bust in the seventies. So, I’m sure there’s a lot more work to be done stateside, but we, we were able to pull together what we could and start this sort of process of, of finding and, and authenticating textiles by Warhol.

JA: This was long slow work, and they were very much out on their own. No-one else had heard of Warhol textiles, and unlike the Modern Masters fabrics these didn’t come with Andy Warhol’s name helpfully inscribed on the selvedge. But what these textiles do have is a look, in particular Warhol used a broken or blotted line to outline the motifs on the fabric: Here’s Geoff:

Geoff: He used that extensively. It’s almost exclusively is. And he drew, drew up on that for all his graphic work. He did do some other work, you know, with other stuff, but mostly the broken graphic line is what he used to describe the work he was doing. It is a line which is broken deliberately. It’s, it is artificially created. He does a drawing and then a piece of paper is pushed onto it, and when you take it off, you’ve got a broken line of the drawing. That originally was just a plain, simple drawing, but now it’s a broken line and it looks like a printed work. And he used that extensively on all his work at that time.

JA: So, sitting in London and scouring the world, Geoff and Richard got their eye in and learned to recognise Andy Warhol’s designs:

Richard: Christies, Sotheby’s, Bonhams, et cetera, et cetera, have sold hundreds and hundreds of drawings and preparatory works for various advertising, et cetera. So there’s a great pool of work to draw on, literally to look at. And so one has these, these sort of traits in his work subject matter, and of course the colouring as well. Mm-Hmm. <Affirmative>, they’re all things that we used as a template really to try and locate textiles that were in that style. And once, once you get your eye in on that, maybe after a couple of years it, it, they kind of jump out at you. They do have a very distinct style. He’s working in that novelty or conversational print in industry really. But his designs have that certain something and I think that’s why they appealed greatly and why he produced or was able to sell quite a few of them because they were exactly what the converters in New York were looking for, for their summer prints, for dresses.

JA: These designs have a joy and a vivacity all of their own. I was blown away by the collection Richard and Geoff have amassed over 13 years of work when I saw it at the Fashion and Textile Museum in London. There are ice cream cones on fabric in pinks, peaches and pistachios, orange and green butterflies winging their way across pretty dresses, broomsticks flying around skirts, quirky pink and purple bugs pinned to full skirts, material printed with hats, socks and buttons, there’s even a dress fabric pattered very successfully with purple, pink and scarlet pretzels. This seems very clearly where Warhol learnt the art of repetition and played with the significance of everyday objects – themes that were to dominate his life as a fine artist. Here’s Richard:

Richard: Well, he was dealing every day with depicting everyday objects, you know, household mass produced objects in his graphic work for journals, magazines, et cetera. So he’s taking those really from the, from the printed page or the drawn page, and he’s putting them into repeats. Those repeats are particularly prescient of the soup cans and the coke bottle paintings of 1962. So, he’s got almost a one up from other pop artists because he is so directly involved with consumerism, advertising, et cetera, et cetera. It’s almost a sort of seamless switch to what he’s doing. Then textile design, as we’ve said, is something that didn’t have a brief or an agenda. So, he was able to play with pattern design, putting things into repeat, repeating motifs all went to inform his pop art.

JA: It’s one thing to learn to recognise what you believe to be a fabric designed by Andy Warhol, but it’s quite another to prove it. Geoff and Richard have managed to do that through assiduous work on a paper trail. They were lucky in that they could talk to a number of people who were still alive who had worked with Warhol directly on these fabric designs, then the chief archivist at the Warhol Foundation, Matt Wrbican, became enthusiastic about their project:

Richard: But he was very encouraging and very enthusiastic about our quest for these textiles. And he was able to point us into directions of where we should look for like-minded artworks design, et cetera, et cetera. And by then, he had also investigated the collections there, and they had found that they had five floral textiles five floral silks, which we actually photographed for our book, Artist Textiles. And subsequently in one of these so-called time capsules, which are actually these, those sort of file boxes data boxes ones that Warhol used to just fill and dump with all associated flotsam and jetsam of his life. And I think there are over 500 of these, something like that. And they’re all in the Warhol Museum. So, there’s things in ones from the later seventies and early eighties that have things from the fifties in. Anyway, they found another couple of textiles, one of the bright butterfly textiles and another one of the Balmoral loom florals. So, he was kind of energized by the whole thing and supported us really.

JA: Then there were papers showing that Warhol had worked for a particular textile company – although not specifically which designs he had worked on, and slowly bit by bit each piece was documented.

Richard: Everything, for the publication of the book had to be put to the Warhol Foundation via Dax. And we had to present what we had in the book as our evidence really, plus other things that we have that aren’t in the book. And from that point of view, everything has been accepted. I haven’t seen any negative reviews yet either of the book or the exhibition, in fact generally people seem to think that it’s a, it’s marvellous to see that facet of his work brought together and the joy and the sort of colour that it brings into people’s lives, particularly as, as we’ve mentioned before the fact that, you know, a month ago particularly, it was cold grey London, and then you come in and you see all this marvellous colour, this sort of saturated colour. So, so far I think everyone is with us.

JA: They are playful and interesting, and just as the Modern Masters fabrics caught the post war American mood, these trap an essence of the late fifties and the very early sixties. The Beatles and Rock and Roll is still in the future but there is something about these fabrics that tell us, – just faintest whisper – that it’s coming. In Richard and Geoff’s book called Warhol: The Textiles, there is a black and white picture of Janis Joplin with friends and family from around 1960, long before she became Janis Joplin – but one of her friends is wearing a skirt in Warhol’s very cool Happy Day print of butterflies and bugs.

Dennis: But I think the thing that I really like about it is, it’s just for me, Warhol’s early illustrations that commercial art period has such a lovely sense of spontaneity, of a sense of humour, of things that I think maybe didn’t necessarily translate all the way through his fine art career. So, some really lovely things. And I’ve always loved Andy Warhol’s early illustration. So, it was really nice to see them in a context that I hadn’t associated them with, which was textiles. And then fashion.

JA: Dennis Nothdruft has curated an exhibition of Andy Warhol’s glorious textiles at the Museum of Fashion and Textiles, in London, but so far they haven’t yet been seen in the US, and as a result this story remains largely unknown there, which is a pity. In time I’m sure that an American gallery or museum will get around to honouring the textile work of one of its greatest artists. But one obstacle, and one reason these textiles were lost was the attitude of Warhol himself: Here’s Geoff:

Geoff: In 1970 a bookshop in New York was going to, well there was an exhibition of the 40s and 50s work. And he didn’t want to know about it. He just said it didn’t happen. It was unimportant. It was just something I did. And that was it as far as he was concerned. Yeah. So it wasn’t important to him. What was important was his fine art. Yeah.

Richard: I think by, yes, by that time he really was focusing on fine art and anything else from that period, 62/3 backwards was, was a hindrance and an embarrassment, which is crazy because it’s such a, a rich and, and fantastic period in his work. It’s very different to the fine art, but it, goes to inform, certainly directly inform his fine art.

JA: Dennis says part of the reason for this is the pedestal on which Fine Art has been placed:

Dennis: I feel that Andy Warhol makes a clean kind of move into fine art. Like there’s that period where we have a transition and then when he fully commits to fine art, he becomes the fine artist. And he closes the very successful studio, he was a very successful commercial artist and graphic designer. But he closes that and he becomes a fine artist. And I think it’s something that the art world has always done. There’s a hierarchy and fine arts, paintings, sculpture are high, and the applied arts, decorative arts, textiles and commercial arts, are low. And that has always existed. I think it’s not quite the same today, but definitely in Warhol’s time. There’s a hierarchy. And you’re a famous fine artist, you’re not a commercial illustrator. So, you can kind of understand why he made that shift and then he became a fine artist.

JA: And yes, says Dennis, this was partly to do with good old-fashioned sexism:

Dennis: Textiles have never been the most sought after. And I think it’s hierarchical and I think it’s sexist if like, you know, I can say that I think it’s, it’s textiles is a domestic sphere. It’s, it’s what women do. And I think historically art history has been dictated by males and the fine artist is the male. And you know, applied arts, decorative arts, textiles are embroidery, are knitting, those types of things are domestic arts and are second class citizens in the art world. And that has always been the case. And that’s changing. There’s that amazing book that’s just come out about a history of art without men and it’s fantastic and there’s so many women who just don’t get a look in and they haven’t historically because it’s been, you know, run by men. <Laugh>. That’s my take on it anyway.

JA: Dennis is right it is changing – and that is one result of women having a louder voice in the world of art. But it is vital for me that textiles aren’t seen just as second-rate art, they are something different, they give you something a painting can’t: Here’s Leigh Wishner again.

Leigh: And there is something that a fabric can do that a painting can’t do, and that’s move. That to me is also a part. whether it’s in a dress and you see it in motion, motion is a changer in textiles. And that doesn’t change with a painting. I mean, you can stand on one side or you can stand on the other and look at it from different, like, raking side views, it’s not built to move. Fabrics are, even something as simple as taking a panel of fabric and letting it fold in a ripple changes the pattern. And it, so it changes the way something looks. It changes your appreciation for it and your interaction with it. And in that way, I believe that textiles have greater powers than paintings. But I understand what you’re saying about the artwork as it translates on the actual cloth. I think certain colours just also glow more from a fabric depending on the substrate that you’re using. You know, if you’re using a sateen or a synthetic, there’s different lustres and properties inherent in the fabrics that can really impart a different level of beauty than just your average painting.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Haptic and Hue, and a huge thank you to Richard and Geoff for their dogged research over 13 years to rescue the wonderful Andy Warhol Textiles – their book is on sale in the Haptic & Hue bookshop, via our website at www.hapticandhue.com Thank you too to Dennis Nothdruft for recognising the joy in these fabrics and creating space for the exhibition, and a big thank you to Leigh Wishner for her role in ensuring the Modern Masters textiles continue to be seen and valued by us all. If you would like to know more about the speakers, or see photos of the fabrics we have talked about, please have a look at the page for this podcast at www.hapticandhue.com/listen. It is episode number 42.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews, and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a member of Friends of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast independent, and free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you extra content every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted Bill Taylor and me.

This episode of Haptic and Hue was about artists and textiles in America, but a very similar movement was going on in the UK at the same time. If you’d like hear more, there’s an interview about this with Ashley Gray of Gray MCA at www.hapticandhue.com/friends called Artists Textiles of the 20th century.

Meanwhile we’ll be back on the first Thursday of next month with another Textile Tale. It focuses on a recycling revolution on the one of London’s most famous streets, Savile Row, where some of the world’s finest men’s suits are made. Join us then to find out what’s happening in the next episode of Haptic and Hue.