Pears and Pomegranates

Episode #30

Five hundred years after the Renaissance it is often paint and art that survives, rather than the fabrics depicted. But the extraordinary skills needed to produce the lustrous and sumptuous cloth that we see reflected in the paintings lit up this age, provided a rich spectacle, and told us so much about how the people of this time wanted to be seen and the stories they told about themselves.

Across Italy, as machines replaced humans those skills have faded almost – but not quite – entirely. This episode explores how people of this era used cloth to convey messages and to maintain their hold on power and authority. It also tracks down two workshops, still functioning today where the old ways are still followed, and ancient skills are kept alive as beautiful fabrics are produced and processed by hand.

The people you hear in this episode are:

Lisa Monnas who is an independent textile scholar and historian. She is the author of the book, Merchants, Princes, and Painters, which is hard to find, new or secondhand, but is the authority on this subject. If you do see it – grab it!

The weaving house of Luigi Bevilacqua can be found in Venice. They have a showroom which you can visit by ringing the bell. Their website is an interesting introduction to the handweaving side of the business. They do also weave velvet by machine at a different location, but it’s not the same. They are also on Instagram @tessiturebevilacqua and on Facebook as TessituraLuigiBevilacqua . You can see a video of Silvia Longo weaving soprarizzo velvet by hand on Vimeo by following this link. https://vimeo.com/712232851

Stamperia Marchi is in the small town of Santarcangelo di Romagna. It is well worth a visit! They are on Instagram as @stamperiamarchi. And on Facebook as stamperiamarchi.

Other books to read if you are interested are: The Merchant of Prato by Iris Origo. This was written in the 1950s by an American writer who married an Italian nobleman. It’s a wonderful description of what it was like to be an Italian merchant on the eve of the Renaissance. You can find it in the UK bookshop and the US bookshop. Embroidering Her Truth: Mary Queen of Scots and The Language of Power by Clare Hunter. This book, which has just been published, is about Mary looked at through her textile records. It begins with a wonderful description of how cloth and fabric were used in the Renaissance and what they meant to people. At the moment this has only been published in the UK, and you can find it in that bookshop.

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Isabella D’Este – one of the most stylish women of the Renaissance

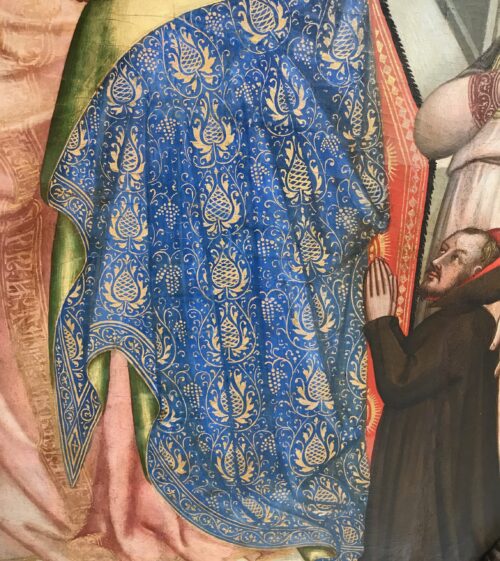

Virgin and Child by Vitale di Bologna

Close Up of her cloak

Bologna Art Gallery

Close up of her garment

Luigi Bevilacqua Handweavers, Venice

Weaving Room, Luigi Bevilacqua

Alberto Bevilacqua

Silvia Longo weaving Soprarizzo

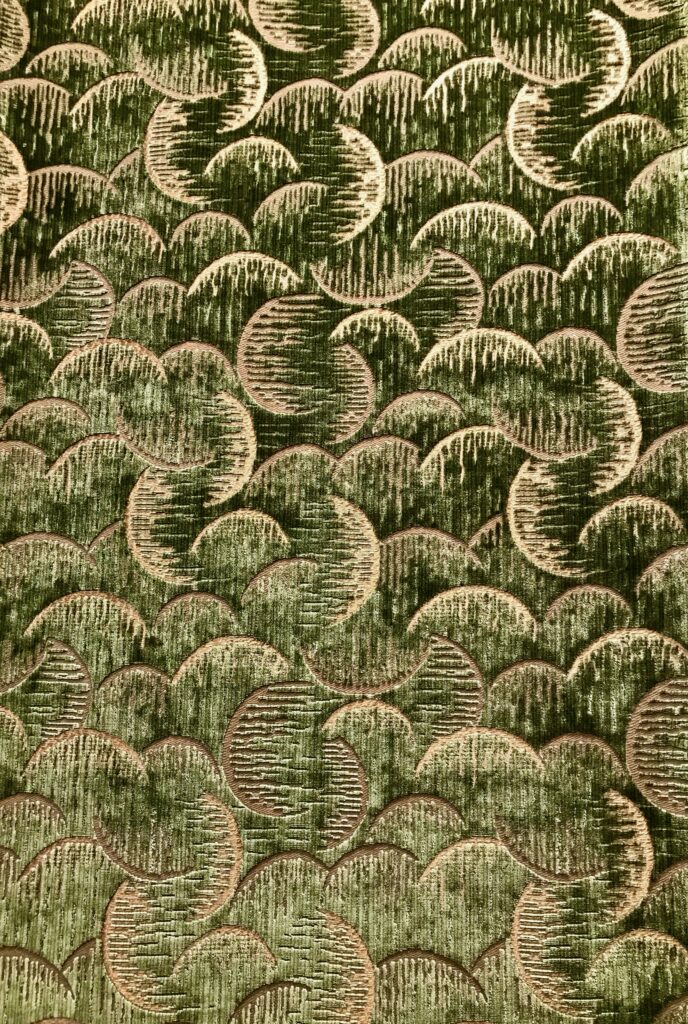

Handwoven Velvet

Modern Design for a Bevilacqua Velvet

Handwoven Velvet

Mangle at the Stamperia Marchi

Stamperia Marchi

Linen being pressed by the giant weights

Gabriele Marchi in his workshop

A Library of Print Designs

Prints by Stamperia Marchi

Alfonso Marchi and the Mangle

Storing Antique Linen

Lisa Monnas

Script

Pears and Pomegranates:

JA: There aren’t many better places to be on a sunny morning than Venice, by the side of a small canal. And that’s where I have the privilege to be in a city still largely empty of tourists. In Italy so much is about the past, reflected in the glory of its Renaissance and Venetian Paintings. I’ve been looking at these and enjoying the beautiful and complex fabrics the people in them are wearing and wondering are textiles like that still made here – can Italy still do that?

Welcome to Haptic and Hue – and Season 4 of Tales of Textiles, called Threads of Survival. My name is Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver interested in what cloth in all its forms tells us about ourselves as human beings. Textiles have an incredible power to talk to us if we can hear them. They comfort and console us, create memories, and define who we are. They can tell others what we think and more than anything they tell us what sort of society we live in.

The Renaissance was a time of glorious cultural, artistic, political and economic “rebirth” across Europe following the Middle Ages. And no-where more so than in Italy with artists like MichelAngelo, Leonardo Davinci, Botticelli, Titian, Raphael, Fillipo Lippi, Fra Angelico, and Artemesia Gentileschi to name just a few – producing art that we still love today.

But take a look at these masterpieces prized as part of our global heritage and you realise that there are other artists there whose work was also hugely skilled, well rewarded, and just as valued by the elite of the day – the princes and kings, duchesses and bishops who could afford to buy it. But the names of these spinners and dyers, these weavers and tailors are lost, and their work has largely disintegrated. We can see it only at one remove through paint. But Italian Renaissance art is dramatically enhanced by the quality of the rich and lustrous fabrics depicted – to put it another way – Renaissance art would be deeply impoverished without the movement, the colour and pattern of the rich textiles they depict.

Lisa: Well, I think that artists look very carefully at the textiles that people wore and that were being produced around them. And it was a source of enormous pride for the silk weaving centres. So, it was in, in some ways an advertisement for their cities to, to, to show off the textiles that were produced in these places.

That’s Lisa Monnas an Independent Textile Historian, and author of the book, Merchants Princes and Painters. She points out that Italy at the time was simply better at many textiles production processes.

Lisa: Well, we know they were very good at it because of the production that we see, the results that we can see they had very good technical knowhow. They were in the forefront of spinning technology for yarn. They had a long tradition of weaving and dying wool. And if you look at the early records in the 14th century of the dying shades available for wool and for silk, they had many subtle shades in which they dyed wool with lovely colours which they called poetic names like apple blossom or dove or something like that where they’re more restricted in silk, gradually the silk industry caught up with that, but they did have these experts already in place from that section of the industry. And the silk weaving technology of course, had to catch up because for the very complex patterns, they needed draw looms that they hadn’t needed for the wool. So it was, it was a question of constant innovation and getting ahead of the game, that was one factor. The other factor for the predominance of Italian silks was the incredible banking and trading system. And so you had long-established colonies of Italians throughout Europe, in major centres, such as Bruges and Paris and London, and in Spain as well in Valencia and places like that. And so they made sure that their products were well represented in the market. And the Italians in the 15th and 16th centuries had quite a monopoly in supplying the English court, with silk.

Both the painters and the people who sat for them used textiles to tell stories – ones that we often need help to decode today. It was an age in which if you wore a hat trimmed with miniver – which was a specific kind of fur, it signified you were a knight or a doctor, if you wore pinks or reds it showed that you could afford these fantastically expensive dyes derived from insects, and of course, it was an era in which only people of a certain standing or wealth were allowed to wear silk and velvet:

Lisa: This was an age where decorum was very important and you dressed according to your status and otherwise you were penalized. And so you would not really have been permitted to wear silk and cloth of gold If you were from a lower class, or if you had an insufficient income, if you were sufficiently rich, you could transcend this class barrier. There was some class mobility. And also I have found that there was a silk merchant in Florence in operating in the mid 15th century called Andrea Banchi. And in his accounts, it shows that some of his silk workers actually did buy silk for their wives, although they were not of sufficient rank to do so. And they would spend sums quite disproportionate to their salaries to try to give their wives some silk, not very often and not very much, but they did. So, you can’t make absolutes out of this really, but as a general statement, they were too expensive for most people to wear. The restrictions really did prevent people from wearing things publicly, but on state occasions and for particular important events for the civic life of a city state, they would suspend the sumptuary laws so that people could wear things well beyond their rank and sometimes beyond their means in public.

So these complex fabrics carried messages about status and power of different kinds: they might be used to glorify the wearer as a divine religious figure, or to show their status as a prince of power, or maybe in an age before photography the picture was used as a diplomatic tool where many reproductions of the portrait would be made to be sent round the courts of Europe.It was a picture like this that the English King Henry the 8th famously saw before he agreed to marry his fourth wife Anne of Cleves. He clearly felt the artist had been far too kind to her when he set eyes upon her in the flesh. But In all these uses cloth played a central role and the more beautiful and sumptuous it looked and the more difficult it was to make and extravagant it was to buy – the better it did its job. Almost the polar opposite of what we have today when fabric is cheap and produced in bulk. So, you would expect the artists of the Renaissance who had to reproduce these complex fabrics to keep a stock of them in their studios so that they could get them right.

Lisa: No. For the simple reason that it was too expensive to be a studio prop. Even damask would’ve been regarded as a huge luxury. If you see inventories of painters’ things, they didn’t own a lot of silk for a start, they didn’t wear silk themselves. It would’ve been, you know, a foolish luxury to buy silks. Neri de Bicci, who was one of the richest painters in Florence in the second half of the 14th century. We, have his Ricordanze which are his daily accounts of expenses and he dressed himself and his children in very good quality wool and linen, but they never wore silk. You were forbidden to wear silk under the sumptuary laws in Florence, unless you belonged to certain classes or had a certain income. And for instance, people like doctors and of law and of medicine and knights were exempt and could wear far better silks, far better textiles than people like painters, for example, who wouldn’t have been allowed. The exception is sometimes their patrons would give them silks to wear. So Andrea Mantegna who worked in Mantua was given silks by the ruler of Mantua to wear because it reflected well on his patron. So, it’s a whole conundrum really, but I I’m sure that they didn’t buy rich silks as props.

Even getting access to see these fabrics was a problem. Painters had to take their chances where they could:

Lisa: People officiating in the church were exempt from some provisions while they were conducting mass. So the churches had an enormous stock of wonderful textiles. Some of them were made from the clothing of lay people, rich lay people who gave them as donations to the church. So they didn’t always have only secular motives on clerical vestments. And artists after all were mainly employed to produce religious paintings and they would’ve had opportunities in the church to study the investments. And I’m sure that’s one way, in another case, if you lived in a silk weaving center, there were, of course, the shops of the silk merchants, but in these shops, the best textiles were kept, locked away. They were so precious, they were locked away carefully, but on days, like in Florence, the feast of St John the Baptist they hung out these silks in a festive way. And also painters could have visited fairs and markets where silks were sold as well. So there were a variety of ways. And also if they were if they attended a procession, or something like that, or obviously saw a bridal procession passing by you, had opportunities to see these silks, how often you got the opportunity to study one carefully, I don’t know.

I love the image of painters on feast days busy scribbling away trying to get down every detail of the incredible fabrics they saw sweeping past, sometimes just for brief moments. So much of what we know about these fabrics comes down to us through paint, as the textiles themselves have often crumbled to dust, but we do know that weavers of complex material like velvet cloth of gold earned well. In the 15th century their wage was the equivalent of a branch manager of one of the Medici’s banks, and it’s been a long time since a weaver earnt the same as a bank manager. But these were truly fabrics of inequality and we forget that at our peril. Not only were certain people forbidden to wear them, they were simply out of reach. Lisa Monnas tells the story of Isabella D’este of Milan who in the 15th century asked her brother in law to buy her a velvet cloth of gold woven with special emblematic designs. Each yard of this precious fabric cost him more than the annual wage of a skilled labourer – He has gone down in the records as a generous man! Those days have gone, but has the making of this kind of glorious fabric disappeared too? Can human hands still fashion textiles like these and is there a market for this and people willing to pay for it?

Alberto: Consider that in the 16th century, in Venice were 6,000 looms for the production of the velvet. Then thousands of people works in the production of velvets and people from all the world coming in Venice to buy the, Venetian velvet. And now we are the last <laugh> producer of this. Otherwise, if you stop this kind of activity, you lose, you lose the knowhow the savoir-faire.

Alberto Bevilacqua runs Luigi Bevilacqua in Venice, which was set up by Alberto’s great grandfather. It is now the last velvet handweaving studio in this city. You can find it in the Santa Croce district where it has been since the 19th century, although Bevilacquas have been involved with textiles in Venice for much longer than that:

Alberto: it’s difficult. I have seen that for example, in a picture of 1499 is written Giacomo Bevilacqua, Weaver. And I have seen that our family was in textile for six centuries.

The painting is by a pupil of Bellini’s and it’s called The Arrest of St Mark in the Synagogue. It was completed in 1499 and delightfully at the bottom there is a little scroll with names of those who commissioned and paid for it, amongst them is Giacomo Bevilacqua who gives his occupation as a weaver. Alberto also knows that some of his forefathers were silk dyers. Velvet weaving didn’t start in Venice but it did flourish here in the Renaissance and later, and Alberto is deeply aware of carrying on those skills:

Alberto: We are very proud to continue this tradition. It’s very important that there is the transmission of the knowledge, otherwise you lose, you lose the possibility. I am seeing, for example, in French, there are some factories like this, they have the same looms, but they have no people that are able to weave and then you lose this.

And for Alberto it is unthinkable – in a very Italian way – that he ends this tradition – he says simply It is important to maintain the past and this for him is explanation enough. All the handweavers at Bevilacqua’s Venice workshop are women, working on Jaquard looms. When we were there they were creating a variety of fabrics, some of them modern velvets like silk leopard and tiger skin, which use hundreds of subtly different shades of colour all on different bobbins, and others were working on weave designs that date back to the Renaissance but interpreted today in modern colours. Silvia Longo has been a weaver here for more than 20 years. She was creating a velvet which only Bevilacqua can now produce commercially; the famous Soprarizzo which demands extraordinary skill of the weaver, an intense simultaneous intelligence in your eyes, hands and feet. She was working with a cotton ground warp, and a supplementary pile warp of shocking pink silk to create the velvet pattern of fruits and leaves and a warm golden slightly metallic silk weft. In making a handwoven velvet after every third pick the velvet warp is cut by eye with a special razor to create the soft pile. But in a Soprarizzo there are patches of cut and uncut weave giving a three D effect where the light falls on them differently. Machines can’t do this – only trained and skilled human hands like Silvia’s. You can see a link to a video of Silvia weaving this on the Haptic and Hue website. She produces around 50 centimetres, or 20 inches, a day, and translated here by Francesca De Stefani, Silvia explains why this gives her satisfaction:

Silvia/Francesca: To see a perfect finished product. And also because she feels that she has contributed to creating that type of pattern. And, you know, so that’s the most satisfying thing.

Francesca: It’s her creature, but she’s because she’s creating each millimeter to it. So she sees its growth. She’s always giving birth to it. Yeah. She tries her best. So since it’s handmade there are bound to be imperfections here and there, but she’s always trying to achieve perfection.

The result is extraordinarily beautiful – these velvets are a joy to touch, as the cut silk moves under your fingertips. and the price? – well Bevilacqua’s handwoven Soprarizzo velvets cost over two thousand three hundred euros per metre, around the same in dollars. So where’s the market for this, who buys them? In the past it was the noble families of Europe decorating their palaces and castles, There is Bevilacqua Velvet in the White House, and the Kremlin, and some very rich corporate offices. But today its more likely to be a line for one of the big Couture Houses to make into a designer handbag or fancy menswear, or perhaps a discrete commission from an interior designer working for a modern Medici – a successful singer, a celebrity or an oil billionaire, or someone who lucked out on a Hedge Fund. Sometimes someone wants a velvet just for them – because they can have it and Alberto believes people see the value in this:

Alberto: The future? Now I think it’s very in Italy, we call it pink, rose, I don’t know if in English <laugh> yes. It’s because I see that is return of interest in this, in this production. There is now there is people that don’t want the massive but wanted some exclusive, because once you have to consider that the very rich people lived in castles in great palace. Now, for example the younger, rich people lives in the Manhattan in London in Beijing some, and then it’s important, for example, to make modern design with the old technique.

And it is that combination that keeps this workshop alive, handcraft married to modern colour and design, something that Italy excels at. This is still the fabric of inequality – not on the same scale as it was in the Renaissance – no one is actually forbidden to wear it, if you can afford it, you can have it. But not many of us can. But the skills of women like Silvia endure because people are prepared to pay for what she produces – and to me the world would be a poorer place without her ability, to create pick by pick, astonishingly beautiful fabric that can trace its origins back several centuries. It would be sad if we lost this knowledge, just as it would be sad if we lost the work of another family in a very different town in Italy.

JA: A couple of hours south of Venice in a small hilltop town close to the Adriatic there is a unique textile survivor hidden away in the streets of SantArchangelo di Romagna. I’m at the Stamperia Marchi. Go inside and you find a print workshop that has been here nearly 400 years, and a giant linen press that looks like something Leonardo Da Vinci might have designed. All of it has been in use since the 1600s

We are not dealing with high luxury here but something very different. This is a country craft kept alive in the past by local Italian families who wanted to decorate the linen that they had handwoven themselves with inexpensive and traditional printed designs, and more recently by the passion of Marchi family who have kept this workshop and the skills it depends on going. The busy and colourful shop above ground at street level is filled with their beautiful prints, apples and pomegranates, twining ivy and pears – all the symbolic designs of renaissance Italy are here – along with some much more modern designs of their own making. You pass through the shop and back into a dark cavern filled with rolls and rolls of antique Italian linen – stored until they are needed. And in the centre of this room built into an old wall is a huge wooden mangle. Alphonso Marchi, father of the current family of artisans tells us more. He is translated by Francesco Boni.

Alphonso/Francisco: This is a unique tool in all of Europe. It was built here in 1633. And at that time, this room where we are standing right now was located outside the city walls because it’s a very large space and it couldn’t be included inside the tiny alleys of the medieval time of the medieval town of that time. They regard themselves as the last guardians of this unique heritage of ancient times that still works today. It’s not fake. We can see and perceive it in front of us.

Mangles have been used for many purposes right back into the ancient civilisations, we know they were used by the Greeks and Romans as an ingenious way of moving loads or exerting very heavy pressure for minimum effort. In this case the mangle is used to put huge pressure on woven linen or hemp to give it lustre and shine and to flatten it. Believe me it makes a real difference! Here a person climbs right inside the giant wooden wheel and walks it round to lift the vast stones on top of the linen to flatten it. This is a glorious machine that Alfonso has come to love:

Alphonso/Francisco: He considers this mangle as an essential part of his family. So it’s like a relative to him. He played a very important role in preserving the mangle and the workshop after the war, when everything, or the ancient crafts were jeopardized and were threatened to be replaced by more modern techniques of production. So alongside his, his being very keen on the job, he developed a very strong passion as a child for what he, what his hand, his father, his grandfather had been doing in previous centuries. But along alongside this, it’s just it’s important role as saviour of, of this, of, of this ancient tradition could be retained thanks to his commitment.

And in a wonderful blend of ancient and modern – that Italy is rightly celebrated for -Alphonso’s son, Gabriel has trained for the New York Marathon on the Mangle. Gabriel’s domain lies beyond the Mangle’s cavern in a much lighter rooms at the back of the workshop. This is where the printing takes place and he is the master printer. There is a store of pear wood blocks, some of them dating back to the 16th century. These are works of art in themselves, drawing on local country patterns from this region as well as Christian motives and emblems of noble families: and if a block wears out Gabriel carves a new one – exactly the same. Each block is inked with a mineral dye – one is made of rust from iron filings – and the recipes are so old no-one knows who perfected them:

Gabriel/Francesco: And the origins of the, of this, of this dye, the recipe of this dye is so old that its actual origin has been lost in time. So they cannot date back to a precise day or a precise name of the author that made it possible. It has been handed down and passed down a generation after generation father to son.

And then once inked, the wood block is stamped onto the pressed linen or woven cotton. Gabriel loves his job and he says every day is different.

Gabriel/Francesco: So beginning in his childhood, very early childhood, he would play with this mould and stamp following the heading, the example of his father and grandfather before him. And then he actually got satisfaction from what he did and found out he, he loved the family’s job, family’s tradition.

The two craft workshops – the Stamperia Marchi and Luigi Bevilacqua in Venice are the polar opposites of each other – one caters to the rich metropolitan global elite and the other draws on the indigenous traditions of the country people of their area. But Alberto Bevilacqua and Alfonso Marchi would understand each other very well – they both share a passion to see complex human skills preserved and passed down to the next generation: Here’s Alfonso Marchi:

Alfonso/Francesco: The workshop and the craft here have been preserved and retained over, over time, thanks to the, the traditions that were preserved and were handed down the generation after generation. So it’s the commitment of the, of the offspring that didn’t surrender and wanted to carry out the, the same job at their, as their ancestors and just not to be forgotten and forsaking in the lapsing of time.

Thank you for listening. If you would like to find out more about either of these workshops or see pictures and videos of some of the processes in this podcast, find links to background reading, or read a transcript of this podcast you will find these resources at www.hapticandhue.com/listen. Haptic and Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production which is supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee. If you would like to contribute you will find the button on our website at www.hapticandhue.com. We would like to thank everyone who has written an online review of Haptic and Hue, these are intelligent, kind and generous and we appreciate them enormously. We would also like to thank the translators in Italy who worked hard to overcome the language barrier, Francesca De Stefani and Francesco Boni both contributed a great deal to this episode, and of course our thanks also go to the staff and management of Luigi Bevilacqua in Venice and the Stamperia Marchi in Santarchangelo di Romagna for opening their doors and allowing us to come in and ask a lot of questions. Join us on the first Thursday of every month for a new episode of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. Next time we’ll be travelling up a creek on the coast of southern England to find out what they were smuggling from France in the dead of night. But I’ll leave you this time with part of a poem by Lucy Larcom, an American poet of the 19th century who spent some of her life in the weaving mills of New England:

All day she stands before her loom;

The flying shuttles come and go:

By grassy fields, and trees in bloom,

She sees the winding river flow:

And fancy’s shuttle flieth wide,

And faster than the waters glide.

Is she entangled in her dreams,

Like that fair-weaver of Shalott,

Who left her mystic mirror’s gleams,

To gaze on light Sir Lancelot?

Her heart, a mirror sadly true,

Brings gloomier visions into view.

“I weave, and weave, the livelong day:

The woof is strong, the warp is good:

I weave, to be my mother’s stay;

I weave, to win my daily food:

But ever as I weave,” saith she,

“The world of women haunteth me.

“The river glides along, one thread

In nature’s mesh, so beautiful!

The stars are woven in; the red

Of sunrise; and the rain-cloud dull.

Each seems a separate wonder wrought;

Each blends with some more wondrous thought.

“So, at the loom of life, we weave

Our separate shreds, that varying fall,

Some strained, some fair: and, passing, leave

To God the gathering up of all,

In that full pattern wherein man

Works blindly out the eternal plan.

“In his vast work, for good or ill,

The undone and the done he blends:

With whatsoever woof we fill,

To our weak hands His might He lends,

And gives the threads beneath His eye

The texture of eternity.