Second Season: Episode #17

A Feeling of Nostalgia

Whether you live in London or Los Angeles, Berlin or Bombay, our buses, metros, and trams use a patterned wool fabric called moquette. It comes in 1000s of different patterns and the sight and touch of each one enables us to reach into our memories and go back to a first love, a journey to school, or friends we have lost touch with. A moquette specialist says every one of us has a moquette that we want to hug. Find out what yours might be and why it matters in this episode of Haptic and Hue’s, Tales of Textiles.

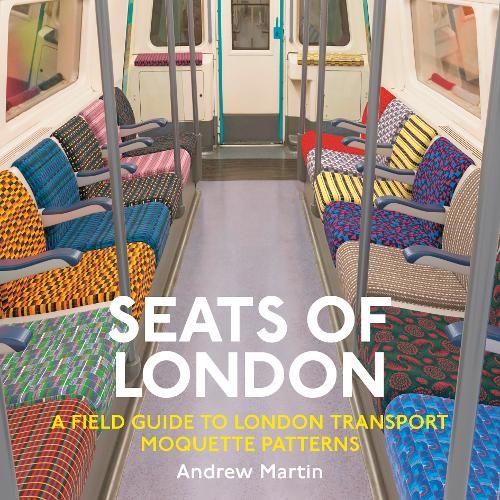

If you would like to find out more about the moquettes used on London Transport, Andrew Martin’s book is called Seats of London – A Field Guide to London Transport Moquette Patterns.

If you would like to source your own huggable moquette, Marcus Mayers at Shed No 2, has all kinds of patterns and moquette products. He can be found at https://www.shedno2.co.uk/ or on e-mail at sales@shedno2.co.Uk or Instagram https://www.instagram.com/shednumber2/

Vintage moquettes can also be seen and bought at: https://www.instagram.com/theheritagemoquettefolk/ and at the London Transport Museum https://www.ltmuseumshop.co.uk/?utm_source=ltm&utm_medium=website&utm_campaign=menu

Ashley Gray of GrayMCA, who is an expert in 20th-century textiles can be found at https://www.instagram.com/graymca/ or at https://www.graymca.com/, where you can see pictures of some of the beautiful vintage textiles he has: https://www.graymca.com/collections/modern-textiles.

Camira is at https://www.camirafabrics.com/en or https://www.instagram.com/camirafabrics/ and has a great deal of moquette on its site!

If you are interested in books on cloth and textiles generally, Elementum which is a small independent shop in Dorset specialising in Nature and Story has a curated Haptic and Hue list where you can view and purchase a number of books. If you would like Elementum to post any of these books outside the UK then please contact Jay Amstrong at jay@elementumjournal.com

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Andrew Martin

Andrew’s favourite moquette Routemaster Tartan

Cover of Andrew’s book – Seats of London

Marcus Mayers

Marcus’s huggable moquette LA Rapids

Moquette on the old Blackpool Tram

New Blackpool Tram moquette

London’s new moquette – The Elizabeth Line

Pink Elefant – Czech public transport

Ashley Gray, 20th century textile expert

The moquette that stopped Ashley in his tracks – Barman by Wallace and Sewell

New London Bus moquette designed by Thomas Heatherwick

Frank Pick, Managing Director London Transport

Enid Marx, Designer

Enid Marx’s Shield, 1937

A Feeling of Nostalgia

Nostalgia is a funny thing. It has a habit of taking you by surprise. A smell, a sound, or a sight can set off a stream of memories like suddenly opening an old box you’d forgotten you had at the back of the cupboard.

There is a bittersweetness to it, as you remember times passed, your childhood, a first love, a journey you made, someone who was part of your life. As we get older these memories come back to us more clearly. They allow us to put things in perspective, understand them in a new way. They are important and powerful feelings.

The French writer Proust famously built seven volumes of writing triggered by the taste and smell of a madeleine – a small, plain, sponge biscuit. How very French that it was food that set off this torrent of words!

But for nations less inspired by food, fabrics have an important role – one that is often unappreciated partly because we see these curtains, this pattern, this sofa every day and we take them for granted, until later when a chance encounter with the same pattern or cloth can set off almost overwhelmingly memories.

And there is one kind of democratic fabric that seems key to inducing powerful nostalgia in almost all of us and that is the fabric of public transit systems around the world. One writer calls them the madeleines of our journeys. Somehow they seem without our conscious knowledge to burn their way into our minds.

And there, there they were that that’s in my memory, that was sort of where they bluey green with a hint of red, but it was the feel of these, of the volcanic was that slightly velvety feel when you touch them, which of course, as a child we were forbidden to do, but there they were that lush velvet and closing my eyes. I can still see the sunlight rushing across them. If you hadn’t didn’t have anyone sitting next to you, you had those shadows and the sunlight literally cascading across. So when you suddenly think of that and you think of those moments from childhood it’s vision, it’s, it’s touch it’s, it’s all of those senses that completely catapult you straight back to where you were as a little child getting on that train

That’s Ashley Gray an expert in 20th-century textiles on how the fabric on the trains he travelled into London on as a child made him feel.

Welcome to the second series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews, a handweaver interested in how all kinds of cloth speaks to us and the impact it has on our lives.

Each of the episodes takes an emotion and unravels how we express that in textiles. This episode – which is the last in this series – is called A Feeling of Nostalgia and it looks at the role fabric and design plays in laying down our memories.

Each of us, depending on which form of public transport we used, and in what era, will have a reaction to different patterns. But from Blackpool to Berlin, from Los Angeles to Lahore a particular type of fabric has been used in buses, trains, trams, and metro systems. It’s called Moquette and it’s that slightly tufted, plush fabric that comes in a multitude of patterns. No one is more committed to this fabric than the British where it is ubiquitous, especially on London’s buses and Tubes.

This is about the district line moquette which is a nice warm colour: orange, black, and mustard. and it’s very popular. In fact, is the most popular moquette that you can buy because you can buy moquette on cushions and things at the London transport museum shop. And I was looking at a display of this D 78 moquette in the museum. The moquette appeared on district trains in the seventies. So hence the name, but also on certain buses in London. And so that goes I was looking at a display of this MCAT at the LT museum when a chap of about 50 came up with his young son, “all the buses I took as a kid at that, on those seats”. He said, “it reminds me of going home from school on the 294, and all the girls from Francis Basely school taking the mickey out of my purple blazer”. I couldn’t work out whether he was addressing his son because he was with a little boy or me, but then I realized he was actually speaking to himself, lost in a nostalgic reverie that the moquette can so easily trigger.

Andrew Martin is one of a number of people who are, in the nicest possible way, obsessed with moquette, and the different designs that have been used down the years. In Andrew’s case, this is the result of being the son of a railwayman with a very special freedom granted to their families.

Well, my dad worked on the railways in York and I grew up in the privileged position of having free first-class railway travel. And I could go anywhere in Britain, first class. And I would do it from the age of about 12 on my own. I would come from York down to London say or just go to Scotland if I was bored. And so I spent a lot of time in what was then compartments, not open carriages so sort of staring at term, but what I didn’t know at the time was called moquette, but patterns on railway seats. And the one that I most remember was the one that used to be in the first-class compartment. So on the London to York service, it was black and grey check. I think it was the first-class version of a blue of a moquette that’s normally blue and was known as Straub, the certain name of the woman who designed it, but it appeared as charcoal and grey in first-class. And you can see that at the beginning of the film Get Carter because Michael Caine is traveling from London up to the Northeast and he’s sitting on first-class Straub moquette, and it’s very elegant and very simple, just black and grey. And if I see that now I’m just transported back to my childhood.

Unusually for a child, Andrew noticed the patterns on the fabric and the quality of the fabric itself.

Well, because I could go into first class. I did notice being a little snob. I always thought the first-class ones were better than the standard or second-class ones. And I noticed that the standard ones were often blue. I’m not very keen on blue as in the moquette colour. Blue just seems to be the default colour. And blue is a chilly colour very often, especially pale blue. And yet now all London buses seem to be, they’re usually pale blue. I find it very dreary and depressing. So I like the first-class ones, which tended to be warmer, richer, and darker colours.

Andrew has spent his life writing about public transport both in fact and fiction. Recently he published a wonderful small book called Seats of London – A Field Guide to London Transport Moquette Patterns. It is a mine of wonderful information – during the Second World War Londoners had to do without their moquette seats and put up with wooden ones. London Transport has more than 400 moquette designs in its files. A good moquette last ten years – that’s ten years of relentless use, people eat, sleep and in some cases die on this stuff and it survives it all.

You do feel you want to sit down in it and you want to linger there, I think ideally on a tube and you don’t want to get off the train. I often have that feeling. I find it quite hypnotic, you know, that is soon disrupted if somebody is shouting or playing music too loudly. But if it’s fairly tranquil, then it’s really nice to just sit down. And so, in fact, sometimes I used to before the pandemic, just sometimes get on the tube and just think I would get off when I felt like it. I would just go around the Circle Line for a while.

Andrew says moquette first became popular in London in the early 20th century.

Well, moquette came in early in Edwardian times, it’s hard-wearing, it looks nice. It holds you into your seat. It has a tuft or a pile, which grips you to your seat, which is useful in London because London is very old and especially around the city, the tube, for example, the lines twist and turn to follow what is basically a medieval street pattern. So we’d thrown around a lot where you’re not ripped in your seat by the out it’s one thing, but it just looks nice. It’s luxurious, it’s good. And people came to expect it. And before London transport, there was competition between a number of different modes and railway companies and they, they were competing. So they strove to provide a good customer service, I suppose. And that meant moquette.

At first, moquettes seem to have been dingy and brown, a bit like London fog, but then as London Transport took shape, and moved into its heyday, Frank Pick entered the scene. Oddly Mr. Pick qualified as a solicitor – and he later became the Managing Director of London Transport in the 1920s. But he had an eye for design that was second to none. Frank Pick is the man behind the famous London Transport red and blue roundel and the elegant 1920s and 30s stations like Piccadilly Circus. He believed the public deserved good design on their trains: Here’s Ashley Gray an expert in 20th-century fabrics, who knows this kind of public design is important.

I think it matters enormously to the quality of what we’re seeing. The critical thing though is to remember that before 1938, all these designs came pretty well, generally it came straight from the, factories. The design wasn’t so effectively thought through. And it was the genius of the likes of Frank Pick when he was appointed to actually want to see something that fitted in with the spirit of modernism that was building at the time. And that’s what began to draw these extraordinary designers in, and they were fresh out of art school, and some very fresh out. I mean, Marianne Dorn was known for her deco rugs, one of which sold at Sotheby’s in New York two years ago for an incredible sum of money. These were real fine designers. It became the people’s art to my mind, these wonderful designs. So bringing these designs out into our everyday lives, otherwise, they were really just the, you know, the playthings of the elite, but suddenly what you had is this change where we had this sort of this access to in our everyday lives to things of great beauty

Frank Pick often choose green for his bus and tube moquettes because he thought it represented the countryside and he believed Londoners deserved a breath of fresh air, and he matched it with red, because to him red represented the city. So many of the early designs were red and green and so many of the early designers were women.

One of the best known was Enid Marx, cousin of the man who invented Communism, Karl Marx. It has always amused me that while Karl scribbled away about freeing the masses from their chains, it was his much younger cousin, Enid, who actually did something practical that brought joy to the lives of millions of Londoners down the years. Enid was born in 1902 and she wanted to be a painter.

Well, I think it was tough. And I mean, go back a little bit further. She’d gone to the Royal College of Art and she’d gone into the painting school and her work wasn’t considered to be up to scratch by the staff at the Royal College. So she was basically forced out of the department and went to work on the design side, on the textile side. Now, how ironic is that? Because during that time, she’s taught by the war artist, Paul Nash, and he actually names her in his article for a signature magazine which became known as the outbreak of talent article. And that included Edward Barrera board and Ravillious, but Enid Marks was, was there. So, you know, it’s so fascinating, real talent, in the end, breaks through. And we see that in spite of prejudice and in spite of all of this, and it took somebody as extraordinary and as versatile as Marks to be able to overcome that.

And Enid Marx overcame it in a remarkable way, she not only designed some of the best known and loved fabrics for London Transport in the 1930s and 40s, designs like Shield and Chevron, Belsize and Bushey. She went onto become one of the first people recognised as an industrial designer. Initially, these designers were often seen as the poor relation of the dress and fabric designers, but Enid Marx’s hand is behind so much of the design vocabulary of 20th century British life:

I wanted to underline this extraordinary character of Enid Marx because for me she was completely, the backdrop or the underlay of childhood for millions of millions in Britain, without ever knowing it. And when one thinks of what she achieved, and it was shown so beautifully in an exhibition at 2018 at the House of illustration, it’s called Enid Marx, Print, Pattern and Popular art. And you walked in and you saw pattern papers from the twenties block, printed textiles and from the thirties utility fabric from the forties, curtains, laminate from the fifties textiles from the sixties, illustrated books stamps from the seventies, and suddenly recognize things that took you straight back to childhood. And you saw things that, that, you know, the Christmas stamps that she designed and I even fell across the most extraordinary thing. There were the 1941 Chatto and Windus publication of Marcel Proust, A La Recherche de Temps Perdu, Remembrance of Things Past, those beautiful designs with the Lee, the powder blue, the hint of red. And when I saw the books there and I remembered my father, having them in, in, in a little hallway, at home, in my home in Kent, dark little hallway, they are beautiful books, they are beautiful designs. I had no idea that they were done by Enid Marx. And the amazing thing with her was that you could go to an exhibition and be transported back to key moments of your childhood through the touch of a fabric through the cover of a book, and literally down to a stand in the corner of an envelope. Now that is design genius.

And in a sense it is the very ordinariness of these fabrics and their setting that seem to give them their power:

it is funny really isn’t it? And it’s only it’s because it’s the very fact that it’s part of the, sort of the utilitarian moments of life, you know, w w we’ve focused on a, to B and, you know, we might be going shopping and we might be going to identity to the doctor or something. But actually, when you think back on the journey, it’s that subtlety of, of the fact that it was what it was the backdrop, it was the backdrop of what was there. And yet it’s only when you think back, and it’s a very clever design that actually immediately attracts your attention. but there was one fairly recently in the last, certainly the last sort of five, 10 years, which is the one that showed the London eye in the design. And I can still remember getting on to I didn’t know where I was panicked in or somewhere, and seeing that design for the first time. And it was so clever that it stopped you in your tracks and in a way that was something that moquette never really did, but that design, which was based on the earlier tradition, had something so contemporary in it. But just for that moment, he registered, it was there.

All the moquettes for London Transport and for so many of the transport systems around the world, including Los Angeles and Berlin, were traditionally made by one company in West Yorkshire. John Holdsworths is nearly 200 years old and it has been making furnishings for buses and trains for over a hundred years. Today Holdsworths is still making moquettes although it is now known as Camira fabrics. And they are still made in the traditional way largely from British sheep’s wool, in a remarkably complex weaving process. Sarah Mallinson starting working for them in the Mending Department when she was 17. Over 30 years later she is one of their Transport Designers.

It’s produced on looms used using Jacquard weaving techniques. The pile is made up of 85% wool and 15% nylon. We have two types of loom. We have face-to-face looms.. This is where two fabrics are woven at the same time. They are woven as one, while the pile yarn moves from the top to the bottom, and then a knife cuts the two fabrics in half. And this cutting is what creates the pile. Then we also have the Metex looms, which just weave one, one piece. It only produces the one layer of fabric and the pile is made by inserting wires across the fabric and the pile yarn loops over the top. So if the wire has a blade, the loop piece is cut, producing the pile and if there is no blade, then the loop remains.

Each moquette is colour tested, fire tested, and put through abrasion tests. The fabrics are rubbed by machines at least 80,000 times just to check that they can stand up to the wear the public inflicts on them. The company has produced the designs for London’s new Elizabeth line – regal purple with grey, cream, and a dash of red. They are also working on new fabrics for the deep tube upgrade programme, including the first air-conditioned tubes – destined to go into service in 2027. But it’s not just London where buses and trains wear British wool, its trains and buses in Istanbul, Sydney, Prague and in a number of American cities too. Sarah says she can usually tell the difference between the designs chosen by each culture and city.

I think the designs the colours do make a lot of difference. We’ve seen a lot of change. They’ve gone from garish designs to more subtle more conservative at the moment. We still do loud colorful ones for different areas. They are very different in the different areas. But I said we work with America. America used to take a lot of graffiti designs because they’ve got a lot of influence now from Europe. They’ve gone a lot more conservative.

And when she goes abroad, yes one of the first things she does is to get on public transport and check out the moquette designs

Yeah, it’s a nice feeling because you’ve been a part of it. I said, my two girls, think I’m crackers because we’ll go places and I’ll say, oh, that’s our so-and-so design. And it’s like, Mum, you’re absolutely Mad, but it’s nice to see it. You see it all around the world.

In recent years the habitat of moquette has been expanding – a bit like a bird taking advantage of climate change, it’s not just to be found on public transport anymore and it can be spotted in all kinds of unexpected places:

And, what I say is everyone has a moquette that they want to hug. The one I want to hug is the Los Angeles rapid metrics in a very vivid, vibrant one. You see people coming along, who’ve got no engagement with railways and they’ll go away, literally hugging a cushion. And that is just a joyful moment.

Marcus Mayers calls himself a railway person at heart. This began as a small child and has never left him. But as well as love for the trains he says the seat fabrics indented themselves on his brain and all of his happy times were spent surrounded by the stuff. Roll forward some decades and Marcus, facing self-employment, realised that moquette offered him an opportunity.

And I realized that there’s a market out there, but people who love trains at that point I was only looking at trains and their wives because there was normally men are into trains. So I hope that that, that, that’s an okay thing to say. Their wives don’t mind incorporating bits of their husbands and love into their house, but they certainly don’t want a dirty, great big oily cog on the front room table. So I thought, well, what if, what if you may, things which reminiscent of railways, which would be appropriate for a modern house and as a result, I just went off on a merry-go-round and started getting into the textures and the different colours and all the amazing things you can do with moquette.

It started with just the Railways buffs but now it’s gone far wider than that, especially when he takes moquettes to shows where people can see and handle it:

There is a pattern for everybody. And when I go to these shows, I normally find that there’s a number of probably ladies I get, again, there’s a bit of stereotyping or sometimes male partners who are trudging around somewhat bored and their faces light up when they see the store and they’ll terminate spent half an hour where they’re, while their partners go off and look at trains and things rummaging through because they love the pants. They love the texture, the fact that it’s got lines and Incruse cruising, and you can engage with moquette.

And then there are the memories, Marcus is a man who hears a lot of stories like this:

oh my God. I remember that I went to a party when I was 18. And when I was drunk, I came home on it, or that is the fabric I used to get on the bus every day to school to. So all of a sudden it opens up this emotional memory that people have this relationship with a past that they kind of forgotten they existed, but it just opens up. So it’s not so much about the MCAT. It’s about remembering the people and the experiences and the parties and the heartache and the joy associated with formative years.

He says there is something subtle about the impact:

It doesn’t matter what age you are over the years, you would have travelled on a lot of public transport, and you may not remember the Marquette that you sat on, and you might not remember the journeys per se, because it will blur into one. But when you hold, when you touch and you feel the fabric and you see the colours of the moquette, it reminds you of that here in a very tangible contactable way, because it’s something which was there and you can touch and feel. And as a result, it brings back the memories that you associate with it. And that can be quite subtle. So you can just be that feeling of being a teenager again or the feeling of having to, you know when you commute to work every day.

And there is something else surprising about moquette – another group of customers for whom it works:

A lot of mothers in particular of autistic children and autistic, there’s a strong, always been a strong correlation between autism and railways. So, for the mothers to be able to give their children a piece of their favourite train is brilliant because it’s kind of thing they could hug. They go hold the smaller items they can put in their pocket. It keeps them calm, it’s replaceable. So, so I get some really nice emails and responses from families who have kids who love trains and have other learning issues. And I think that’s one of the things I’m really passionate about is it helps connect them, helps them keep them in reality. And I get so much joy out of that bit at the market.

So wherever you are, on a bus, a train, a coach, in Sydney, Dublin, Chicago, London, Los Angeles, Delhi, Wellington, Prague, or Berlin, have a look at what you are sitting on. It’s remarkable stuff with a story that goes back nearly 200 years to the dawn of the railways. It might be, in Marcus’s words, the moquette you want to hug – that special one that brings back memories and a Feeling of Nostalgia. Here’s Andrew Martin, Author of Seats of London, on his favourite design:

Maybe the tartan that was on the old route master buses. the Routemaster was like being in a rather slightly rackety gentleman’s club. And that’s, that’s what you felt that you should be lighting up a cigar, which had probably some people to hit. When you, when you’re saying there, and it was just so mellow and so warm and both from the outside looked so attractive because of the moquette, because of the sort of yellowish foggy lighting. And it was like a lantern moving through the streets of London and you want it to be in it.

Thanks to Andrew Martin and Ashley Gray, to Sarah Mallinson at Camira Fabrics in West Yorkshire, and to Marcus Mayers at Shed Number 2 for sharing their knowledge and their wisdom of this curious corner of Tales of Textiles. You can find pictures of some of the moquettes discussed in this podcast on the website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen, where you will also find a full script of this episode.

This is the last episode in this series. Before I sign off for the northern summer I wanted to thank all of you who have supported Haptic and Hue and invested in Series 3 by Buying Me A Coffee. I have been overwhelmed by your generousity. All of you will own a piece of the new series which should start in September. I hope you enjoy your investment.

Thank you for your company, your suggestions, and most of all for listening.