No Costume? No Carnival!

T

Episode #38

T

This episode looks at how different Carnivals developed and how textiles and masks play a central role in the ideas behind these festivals. We start in Venice a thousand years ago with a carnival created to allow the poor to let off steam once a year, and to imagine themselves, with the use of a mask, as equal to the rich. We cross the Atlantic as the rich plantation owners brought Mardi Gras to the Caribbean. There it was creatively extended and developed by the enslaved and the poor into a series of glorious feasts of costume, music, and dance. We track Carnival as it was re-shaped and brought to Britain by Caribbean migrants, as a celebration of their culture and community. And in all of these, this episode looks at how textiles and clothing play a central role.

The people you hear in this episode are.

Dr Christine Checinska: whose website is at https://christinechecinska.com/ . She is a curator of the current Africa Fashion exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London.

Francesca de Stefani – who is a Venice City Guide https://bestveniceguides.it/de/guida/francesca-de-stefani/

Pennie Mendes, Fashion Designer,

Pax Nindi who is a Global Carnival Director and the founder of http://www.globalcarnivalcentre.com/pax_nindi

Pennie has very kindly provided a number of links and books about Carnival for anyone who wants to study further.

The Traditional Mas Archive: https://traditionalmas.com

Youtube videos with former Mas Performers in Peter Minshall’s bands:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qzapc21MXRg

Peter Minshall talking about River and other performances: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=37mqAho09N8

An Article by Nicholas Huggins about Peter Minshall’s work. https://nicholashuggins.wordpress.com/2015/10/20/the-work-of-peter-minshall/

“Can a Masquerade Salvage Humanity’s Declining Star in the Era of Spectacular Power?” Clair Tacons https://www.clairetancons.com/writing_spring/

A Decade with Minshall by Sean Drakes. https://www.caribbeanlife.com/a-decade-with-minshall/

“Carnival, Camboulay and Calypso; traditions in the making” John Cowley. Academic study of the origins of Trinidadian Carnival music.

‘Parade of the Carnivals of Trinidad 1839 -1989” Michael Anthony. This can only be bought secondhand – try www.bookfinder.com

“The Dragon Can’t Dance” by Earl Lovelace. Prose work about Carnival: Can be bought new or second hand from www.bookfinder.com

“Play Mas” Mustapha Matura: Play about Trinidad seen through the lens of Carnival:

Dr Christine Checinska

Modern Venetian Carnival figure

Modern Venetian Carnival figures

Francesca de Stefani

Dame Lorraine figure, Trinidad

Dame Lorraine figure Trinidad

Pennie Mendes

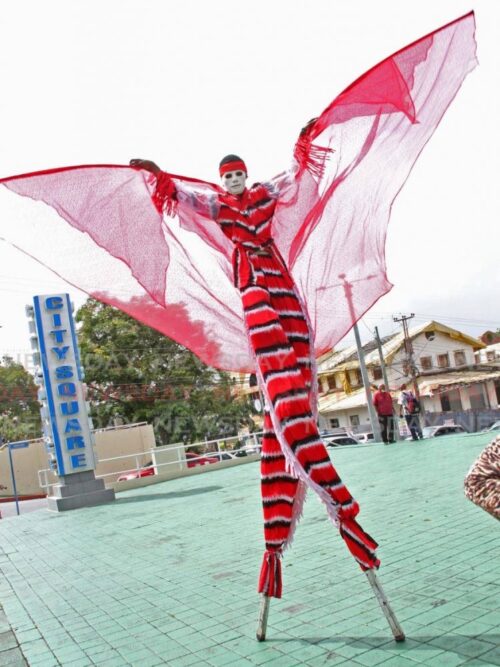

Moko Jumbie figure, Trinidad

Moko Jumbie figure, Trinidad

Peter Minshall

Peter Minshall’s Midnight Robber

Man Crab with Washerwoman behind him

Sherri Ann Guy, Hummingbird, 1974, Photo copyright Noel Norton

Participants in River, Pennie Mendes’ photo

Participants in Callaloo, Pennie Mendes’ photo

Peter Minshall’s Papillon

Madame Hiroshima

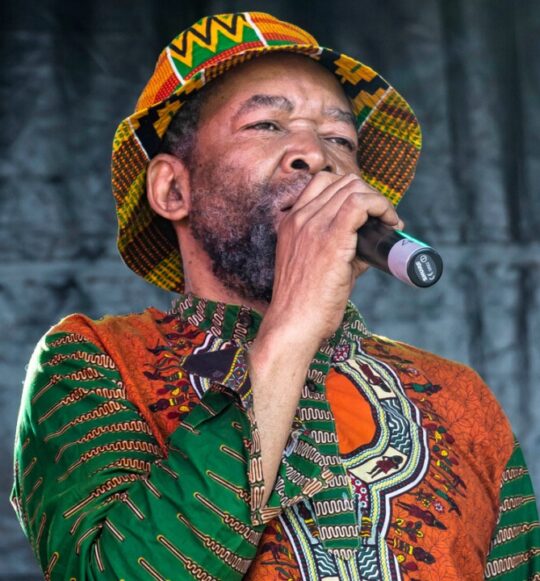

Pax Nindi

Script

No Costume? No Carnival!

JA: It’s Carnival time in many places around the world – and the first thought for most of us will be this is a giant party with music and dancing and, yes, lots of people dressed in not very much except bikinis and beads. But down the centuries, the reason Carnival has become such a special festival and what lies at the heart of it is the way people have used textiles to transform themselves. Above everything, Carnival is an opportunity for people to dress up, put on a mask and a costume, and leave themselves and their troubles behind, and for a few brief hours become someone else.

Christine: I think Carnival is really special because it’s a power reversal that happens typically in Carnival. If you look at the history of Carnival across the world and Masquerading Carnival in West Africa and the Caribbean. Donning the carnival costume. It’s not just about kicking up the heels to a great sort of Calypso track or a dance hall track. It’s subversive, you know, it is about upending power relations for that weekend of Carnival. So it’s, it’s almost a sort of a twilight time or a twilight zone that happens within Carnival. Things are never quite what they seem, but it, for me at its heart is that it’s actually about politics. It’s about freedom. And I think costume plays a key role in that, in the acting out of that.

JA: That’s Christine Checinska, who is an artist, curator, and story-teller and this episode of Haptic and Hue is about the power and the joy of Carnival and the central role textiles, and masks play in the mysterious process of enabling people around the world to become shapeshifters and assume new identities. Welcome to Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles, my name is Jo Andrews, and I’m a handweaver interested in what textiles tell us about the story of humanity.

No one knows where and how the practice of using textiles to assume a different identity, dressing up, developed, or where the idea of Carnival comes from. We know that the word itself means literally, farewell to meat, as in the Christian calendar you were giving it up for Lent with its bare tables and empty cupboards, before Easter and the start of the spring growing season. Some have suggested that the great feast is related to the Roman Saturnalia festival when strict Roman dress codes were overturned and according to one ancient account: ‘Everywhere there is clapping and singing and playing games, and everyone, slave and free man, is held as good as his neighbour”. Sounds a lot like Carnival to me. In Europe, the first place a festival called Carnival seems to appear is Venice, where it can track its history back eleven hundred years. Francesca de Stefani lives in Venice. She is a city guide knowledgeable about Venice’s history. We talked outside by one of the little canals and, yes, you can hear boats passing in the background.

Francesca: Carnival is a Christian festivity that was celebrated all over the Christian world before Lent started. So it was actually the last opportunity, you had to do whatever was going to be forbidden during lent. So, parties drinking, eating meat, anything you can think of.

JA: But in Venice the governing class turned it into something more:

Francesca: And so the only social class with power and political rights were the wealthy merchants who have always been very smart, because, to them, political power was worth more than money because as long as you stay in power, you can keep doing excellent business. So how did they manage to prevent revolutions and keep the general population happy with a lot of different political tools, by giving them privileges? Among these were the way they were celebrating Carnival. So whenever they were celebrating Carnival here, everybody had to wear the same white plain mask. So back then it wasn’t a Carnival, you think of nowadays where you dress up, like fancy dress. It was like you were going to a party, you were celebrating, if you wanted to dress up, up, you were dressing up, but in better clothes than usual. But everybody had to wear this white mask that would make you anonymous. So at least during Carnival, everybody felt they were equals, even though they weren’t. Okay. And this mask also allowed you to eat and drink without having to take it off. So, while at the end of the day, you could recognize who was who, because you know, of the stature or the way they were moving, but that was the idea.

JA: And the idea of being masked not only gave you a measure of equality it allowed you to change:

Francesca: And then over the centuries, they realize that wearing your mask and hiding was quite an interesting phenomenon. By which I mean when you’re wearing a mask are masked, or are you actually showing your true face, because obviously, people start to behave in a different way, you know? And so slowly, whenever people were celebrating private parties, which were quite particular parties later on in the history of Venice, they started to wear different masks as well.

JA: What the Venetian State wanted was for Carnival to act as a kind of safety valve – a way to keep them in power and it was part of a set of levers that worked. Venice’s independent mercantile government survived for nearly a thousand years.

Francesca: The state was actually organizing, you know, public receptions and games, you know, so in order to allow the population to let off steam, to go crazy, to go wild. And I don’t know how familiar your listeners are with Venice, but Saint Marks Square is divided into three parts. There’s the main part, which is in front of Saint Mark’s church. And then there’s the small Saint Marks Square, which is the part facing the water. There on Fat Thursday, the state was organizing kind of a wild party slash ritual commemorating a victory they had in the 11th century over the Patriarch of Aquileaum. And so just to scorn him, the Patriarch was then forced to deliver one bull and 12 pigs every year. And so these animals were then being slaughtered on the square, and the meat was then given to the people. Okay. And in this part of the square, they also organized games. A really popular one was the strength of Hercules by which different teams had to build human pyramids. So the taller these living sculptures, the better. One of the criteria by which you would judge was also creativity in shape, so not just the plain pyramid, so to speak. And then once you had finished the shape, you also had to be able to rotate, rotate around yourself, 360 degrees without having anybody falling off this living sculpture. So, these teams were actually training for the whole year you know, to be the winners. There was no money involved, but it was, you know, people were very proud, you know, well, I guess human nature never changes. They have always been very competitive.

JA: But at the centre of Carnival is this idea that for a few days you can, with the help of a mask made of papier maché and some textiles, become someone else: Here is Christine Checinska again:

Christine: We’re speaking about this idea of turning things on their head and transforming, becoming someone else. And I think that that is what the costumes bring to Carnival. It brings that power of transformation, and you get a sense of the ritual of dressing. You know, when you see these wonderful carnival performers that, you know, they’ve taken hours to get ready. They’ve taken hours to make the costumes, to design them, to make them, and then the ritual of getting dressed. And I think it’s all part of this idea of transformation, and it’s a magnified version of what we do every day. Actually. I think we, many of us have, you know, favourite clothes or the one pair of jeans that you feel great in, and you become a bigger version of yourself. You know you become more confident that you feel that you have maybe a more can-do attitude changes your mood. And I think that carnival costumes operate in a similar way. So as we put on the costumes, we absolutely inhabit that character.

JA: One of the joys of Carnival is that it adapts itself to the culture and the needs of each society where it grows. It crossed the Atlantic with Catholic plantation owners in the 1700s. On the Caribbean Island of Trinidad, French settlers and free people of colour held elaborate masquerade balls for Mardi Gras. Tradition has it that enslaved people watched through the windows and decided to hold their own celebrations, not so much to mark Lent but instead to celebrate the burning of sugar cane, so the festival became known as Cannes Bruleés and then Canboulay:

Christine: These were the three days of freedom that the enslaved had. And so these were the days where they could inhabit those powerful political positions, you know, those powerful characters. They could, you know, present themselves as landowners present themselves as generals present themselves as people with power and poke fun at the real people with power.

JA: In Trinidad, Carnival developed its own music, Calypso, and later Soca, and its own characters. One of the enduring figures is Dame Lorraine, who is now several hundred years old, often a man dressed as a woman, her role was to mock the elaborate fashions of the French planter’s wives, as Pennie Mendes a fashion designer, who worked on a number of Trinidadian Carnivals explains:

Pennie: She is characterized as a voluptuously large woman who wears long dresses. And the liberated slave would mock the original 18th-century French court dress complete with, elaborate with fans and hats, but made them distinctly in their own fashion, using materials that were readily available, such as assorted rags and imitation jewellry, and emphasizing and exaggerating the physical characteristics by putting pillows or stuffings down them to make their bosoms, <laugh> bosoms and their behinds, larger <laugh>.

JA: Trinidad has a wealth of different cultural traditions to draw on for its Carnival, not just West African storytelling and mask traditions or Northern European feasts, but also Bengali and Bihari cultures from its Indian indentured labourers shipped there by the British Colonial authorities, the indigenous Caribbean population, Syrian and Lebanese people who came as haberdashery merchants and Portuguese who sold food and hardware. It all adds to the rich mix Trinidadians call Calalou:

Pennie: Then you have the Moko Jumbie, the Moko jumbie, oh gosh, a wonderful, wonderful character. They’re stilt walkers and they’re originally from an African cult figure, and they dance on stilts as high as 14 feet high: I mean, they must practice for ages and ages and ages. And then there’s the midnight robber. Love this one, the midnight robber. He wears a long floor length, dark cloak and a wide-brim black sombrero hat. And he has assails his victims with long-winded speeches of doom and gloom. And this is reminiscent of the African storytelling, the griot character from the Yuruba District in Africa. And then you have the Souymayree character, and she performs, yes, it’s a she, performs to tassa drum music and the character is derived from East India culture of Diwali. And this character dances in a bamboo frame in the shape of a donkey.

JA: But Trinidad’s carnival has always had a political edge, particularly in the unofficial events:

Pennie: So Jamborees called Jour Ouvert which were outlawed, were organized to be held before dawn on a Monday morning to mark the opening of Carnival. This still happens today. These jamborees would always reflect the mood of the rebellious street people. It was a time for them to display their wit and, and satire in Pecong patois. People dressed up as imps and jab-jab devils, some covered in blue paint wearing just a loin cloth and horns on their heads. And they would prance in the streets holding up placards with insults and jibes at their former masters, and the governments and many of them went to prison for the right to dance uninhibited and for defying colonial authority control.

JA: Other Caribbean islands have their own traditions. Jamaica celebrates Junkanoo at Christmas and there too they draw on incredibly diverse costume and cultural sources. One of the Carnival characters is called Pitchy Patchy, whose role is to stop Carnival from getting out of hand: Here’s Christine Checinska.

Christine: And there are theories about his costume being related to the Jack and the Green costume, which is a costume made up of layers and layers of leaves in UK traditions. And so then Pitchy Patchy is this kind of creolised coming together of the kind of Jack in the Green Leaf costume with west African, Ghanaian masquerade traditions to create certain characters, costumes, Pitchy Patchy, covered in rags, multi-coloured sort of fragments of cloth oh, I want to say to make mischief in. But Pitchy Patchy is the person that kind of keeps the carnival masquerades and performers in check, you know, and almost sort of oversees the carnival in all of these multi-coloured strips. But you absolutely get a sense of people becoming Pitchy Patchy, taking on that role as they don the costume. It’s really about the power of fashion to transform us in everyday life. And then, you know, as I say, in a magnified way within the world of Carnival.

JA: But these elaborate costumes across the Caribbean were first developed by people who at that time owned nothing, they were enslaved or later very poor, so how did they create such wonderful things?

Christine: It was a mixture of, being handed down pieces from the masters, bartering and swapping and exchanging garments between themselves, military costumes. Remember plantations were spaces of violence, of cruelty. And I think it’s Kamau Brathwaite, the Jamaican historian, that famously said that, plantation slavery systems were cruel, but they were creative. So, there is this kind of will to survive and this will to adorn that feeds into this customization of clothing. The wearing of hand-me-downs, the wearing of military costumes that may have been seized by someone who had fallen, for example. The collecting of trimmings, whether it’s ribbons or buttons or epaulets. And then using that within one’s clothing, particularly during this Christmas festival season. So, it was a mixture of what you were given, what was handed down, what was purloined, I’m going to say, because I’m sure there was that going on, and then what was exchanged., it is always quite hard to speak about because I’m obviously not condoning enslavement, but what I sometimes want to consciously celebrate is the power of the people that survived. the ingenuity, the creativity. And for me that that kind of creolisation that happened in that, you know, as cultures came together and the tensions between them, that’s when you get these wonderful flowerings that are Caribbean Carnival that is the Notting Hill Carnival and various other carnivals in the UK and elsewhere now. They come out of that tradition of the clashing of different cultures, the upending of power structures, the embracing of the power of costume to transform.

JA: Carnivals wax and wane as the community needs them and invests in them. In Venice it died out altogether until it was revived in its modern form in the 1970s. In Trinidad in the 1970s and 80s it stepped beyond its origins and became something different. At the heart of that change was man called Peter Minshall, who in 1974 was asked to make a Carnival costume for his sister Sherri Anne Guy, who was just thirteen at the time. With the help of 12 people working on her costume for 6 weeks he turned her into an iridescent, trembling, hummingbird. Pennie Mendes, who spent many years working for Peter, describes the impact it had.

Pennie: He said this little thing, because Sherri Ann Guy was this very petite girl, right? This little thing exploded like a joyful sapphire on that stage. And then 10,000 people exploded with her. And he realized that mas could be a high form of art and communication. And so it was, and Minshall for that costume had studied how bats were engineered or structured, and used that as a guide for his costume. The hummingbird’s wings made, for Sherry Ann Guy were made from cane cloth and feathers. Her arms extended horizontally out, and the wings came right down to the floor and caught onto each of her feet. it allowed Sherry Ann total mobility, total, total mobility. She was able to freely dance, rapidly fluttering her wings to the music. And as, as if she became the hummingbird itself, I can just see that. So that was Minshall’s innovative carnival design where cloth became truly, truly kinetic if that makes sense.

JA: And from then on Minshall effectively re-designed Carnival and told huge global stories. Until then Carnival Kings and Queens had been on static floats trundling through the streets of Port of Spain. That wasn’t what Minshall had in mind at all. He created stories using two and three thousand performers wearing elaborate costumes with ten foot wing spans or battling with each other in representations of good and evil. One critic wrote “It is doubtful that the work of any single individual has had so instantaneous and so searing an impact on the consciousness of an entire country.”

Pennie: He took the streets of Port of Spain as his own theatre, and the masqueraders became performers in the stories. And throughout Minshall’s whole career, these stories evolved as visual explorations on wide world issues, such as environmental problems. political and social issues, on capitalism, greed, disruption, and exploitation. For instance, in 2006, his band The Sacred Heart was an army of urban samurai cowboys and girls marching against hate, selfishness, disease, and prejudice. These works of art created a platform for political debate and controversy. So, they were not just pure revelry. You could join the band and do the revelry, but you also could join the band and have a political message. And that was the genius. He didn’t take the joy out of Carnival.

JA: Above all Pennie says that Peter Minshall understands the magic that happens when someone puts on a costume:

Pennie: He said: “Trinidad Carnival”, because he, to me, he expresses everything far better than anybody else. <Laugh> Trinidad Carnival is a form of theatre, except the costume assumes dominance. So what you wear is no longer a costume. It becomes a sculpture, whether it is a puppet or a great set of wings. Once you put a human being into it, it becomes a dance. It begins to dance. The costume begins to dance. And this he said was his discipline. He said, I have the streets, the hot midday sun. I have 2000, 3000 people moving to music. I put colour, shapes and forms onto these people, and they pass in front of the viewer like a visual symphony. The artist in Carnival becomes a medium through which people express themselves.

JA: The Streets of Port of Spain reverberated to Peter Minshall’s grand narratives. “Paradise Lost” complete with fallen angels, imps, and a serpent, “Papillon” which released two and half thousand human butterflies with ten-foot wing spans onto the streets to demonstrate the fragility of life. “River” in 1983 was a battle between the pure river personified by his queen, “Washerwomen”, dressed in white with rows of washing pegged out above her head, and his king “Mancrab”, representing greed and selfishness. “Madame Hiroshima”, from his band Callallo personified the evil of the nuclear bomb and later led a Peace March in Washington in 1985. His designs and performers opened both the Barcelona and the Atlanta Olympics in the 1990s

Pennie: You know, you felt working for Minshall that you were in the middle of something very new, very creative, and very wonderful. He looked at the craftspeople in Trinidad, the metal benders, the foam makers, the leather makers, all the technical craftspeople to help him produce the works, right? I worked with out workers and it was just a wonderful experience. For me, It was better than going to art college <laugh>. I learned so much <laugh>

JA: Meanwhile back on the east side of the Atlantic, Trinidadians and other Caribbean migrants who’d come to Britain after the Second World War repurposed Carnival yet again to make a new political statement. In 1958 there were race riots in Notting Hill in London. After that bitter event, a Carnival was organised so that West Indian families could celebrate their own culture and gather as a community. For five years it was held indoors before it took to the streets in the 1960s:

Pax Nindi: Personally, I look at it like that was a statement to say, whether you like it or not, we are black as black as you want, but we’re here to stay. So we’re going to beat our drums, we’re going to play our steel band until you read, have that understanding of who we are.

JA: That’s Pax Nindi who is Zimbabwean and a global carnival director. He runs and mentors Carnivals all over the world, He has organised them in places as diverse as Abuja and Oxford, Bosnia and Accra and he says they are all different:

Pax: Well, every country has got a different feel about Carnival, a different reason for doing carnival, different themes and so on. But at the end of the day, when people see it, whoever sees it generally, there’s always one thing, that it looks like a celebration. Now you might be somebody from Brighton or from Zimbabwe who lives in Brighton. When you see that celebration, it becomes part of you. It’s like, really this is our community. We are celebrating together because with Carnival there’s no language. You know, you don’t need a qualification to do Carnival. So, it allows everybody to take part. And by yourself, carnival, if you are by yourself, you’ll never get a carnival going. It has to be a community. That’s what people love about Carnival.

JA: He also says that lots of cultures do carnival – they just don’t call it that – even in Zimbabwe there are events like Carnival:

Pax: Now the interesting thing is if you come in my village and they see a chief, a new chief being ordained, right, or getting married, when you look at it, you tell me that is the best carnival you have ever seen all your life. So we do this naturally, but we don’t package it as Carnival. But what’s happening at the moment, if you go now to Zimbabwe, Ghana, and so on, they will tell you they’ve got a carnival. But what we’ve done is we just packaged what we normally do and call it a carnival. Then for tourism is good, but culturally that is sort of like, it loses its value because now it’s become commercial. So that, that’s, that’s what it is, really. Because people say you don’t do carnival in Zimbabwe. We know we don’t, but we do <laugh>.

JA: And in Britain too there are much older traditions of challenging authority that predate modern carnivals, medieval festivals that were called upside-down-days, where there were Kings and Queens for a day, and the poor became equal to the rich, and in some northern English towns a trace of that just about survives in the tradition of mischief night. But today modern carnival is less about art or protest and more about money and tourism. Carnival, whether it’s in Venice, Rio, Notting Hill or Port of Spain, brings in money and that’s a problem because it shuffles out the craftsmanship and the meaning: Here’s Pennie:

Pennie: It seems today in our body-conscious environment that the Modern Carnival is all about masquerading in just beads, feathers, and bikinis. I hope that doesn’t sound harsh, but it’s a modern Mardi Gras and, it sort of is about commercialism, catering for tourists. We didn’t cater for the tourists in the eighties and the nineties. We hardly saw tourists, right? And so being the sort of beads and bikini and feathers carnival, many of the costumes are made abroad, I was devastated to hear. The Trinidadians are in dire danger of losing their skills, their carnivals, crafting skills.

JA: But Christine Checinska is more hopeful:

Christine: I think there will always be people that see it as that just a big party, but equally I think that it will become so exaggerated, so party-like, I think when it gets to that extreme stage, we’ll then find smaller local groups that feel, no, this is part of my heritage. You know, for many of us of Caribbean heritage in the UK, Carnival, traditional Carnival, was the only time that our culture, was being seen. So I think there will always be those of us that feel, no, this is part of our history. We want to keep the history and the roots of actual Carnival alive. So I, I think almost like, you know, when a flower goes over is what I want this a picture I have, and I think that that’s what will happen. But out of that, I would hope comes maybe smaller localized carnivals run by people for whom it is central to their history or our history. I think there will always be a need for everyday people to protest or to have a sense of freedom from everyday life. And, I think Carnival will continue to be a manifestation of that, that desire and that working through of that push against society.

JA: Thank you for listening to this episode of Haptic and Hue, and a huge thank you to Francesca, Christine, Pennie and Pax for sharing their wisdom and insight about different Carnival traditions. If you would like to see pictures of some of the Carnival figures and the different performances that they spoke about, or read a full script of this podcast, you can find them on Haptic and Hue’s website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews, and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a member of the new Friends of Haptic & Hue, which costs £50 a year or £5 a month. This keeps the podcast truly independent and free from sponsorship and advertising, and brings you extra content every month. If you’d like to find out more, it’s on the website at www.hapticandhue.com/friends.

Next month we will be unravelling the mysteries of the Derbyshire Records Office where Haptic and Hue helped to uncover an extraordinary piece of cloth survivor that has a tale of its own to tell.