Is The Needle Mightier Than The Sword?

The Secrets of Ancient Textiles and Tools

Episode #37

In this episode of Haptic & Hue we talk to one of the world’s most eminent textile archaeologists, Margarita Gleba. The evidence that she and others like her are piecing together for the first time from precious ancient textiles tell us new stories about how human beings organised their families, farms, towns, and cities, waged war and traded, how they expressed ideas of status and identity in clothing and how they used textiles in every corner of their lives. Some of the greatest mysteries of our existence remain to be unlocked and their secrets may lie in the textiles that have not yet been properly analysed or researched. Listen to Margarita Gleba as she takes us on an expert tour of the deep past and, with her knowledge of textiles, begins to sketch in some of the gaps.

Margarita Gleba works at the University of Padua in the Dipartimento dei beni culturali, Her book: Textiles and Textile Production in Europe: From Pre-History to AD400, written with Ulla Mannering can be found in the Haptic & Hue UK and US bookshops. Dressing the Past – an anthology of how and why ancient people dressed as they did, can be found in the UK bookshop

There is a YouTube lecture on Unravelling the Fabric of the Past that Margarita gave five years ago to the British School in Athens which you can watch here.

If you would like to know more about Must Farm, their website is: http://www.mustfarm.com/ .Susannah Harris, who worked on analysing the finds with Margarita made a series of short videos about the textiles which you can see at http://www.mustfarm.com/post-dig/post-ex-diary-11-the-must-farm-textiles-part-one/ Weavers will be most interested in the third episode!

There is also a Facebook page for those interested in archaeological textiles called Archaeological Textiles Newsletter at: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100064843172033

You can follow Haptic & Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic & Hue name

Margarita Gleba at Work

A Ball of Yarn 6,000 years old, La Tene Museum, France

Tabby Weave 9th-6th century BCE from Cumae near Naples

Yarn from Must Farm 1000-800 BCE

Fine Yarn from Must Farm 1000-800BCE

Must Farm Site – Late Bronze Age

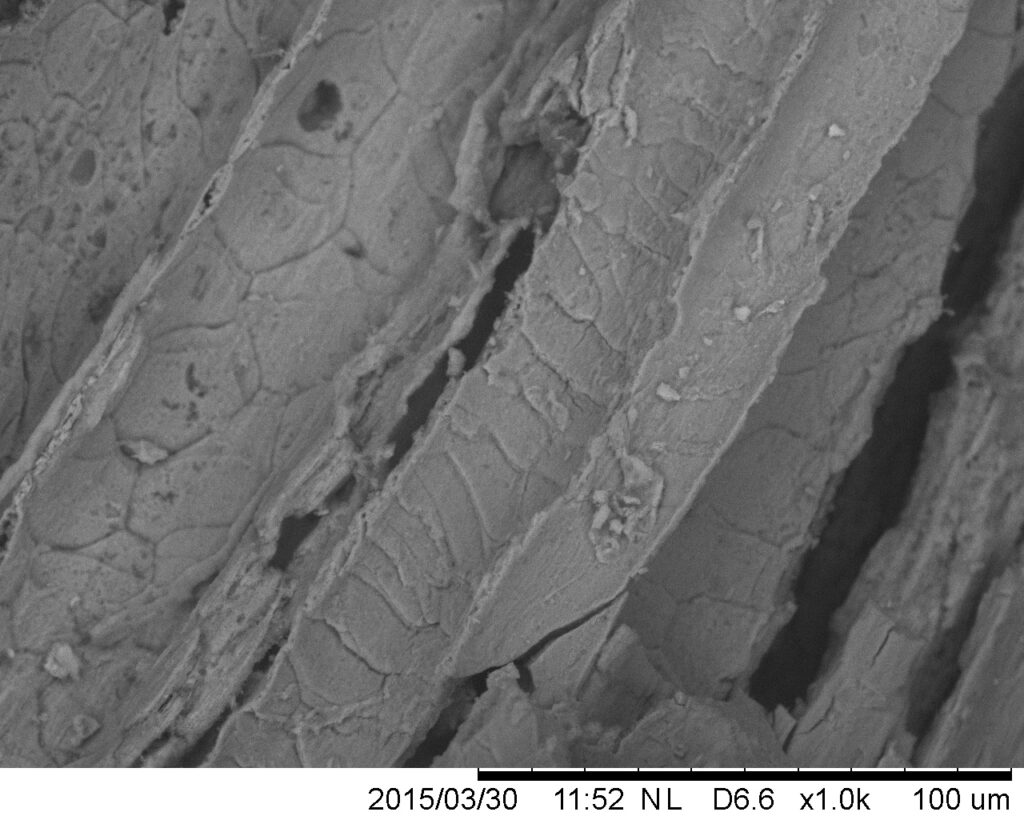

Mineralised Yarn under a Microscope

Magnified Plain Weave – Plant material

Twill Weave from Etruscan Settlement north of Rome

Ancient Needles From Siberia

Ancient Needles from Siberia

The 25,000 year old Venus of Willendorf with a Net on her Head

Is the Needle Mightier Than the Sword?

Script

JA: Sometimes to go, forwards, we need to go backwards – a long way backwards to the beginnings of human existence – if we want answers to vital questions like when were textiles invented, when did we start wearing clothes and how old are needles? These questions are fundamental to our humanity and yet very little attention has been paid to them in the past.

But recently a new kind of archaeologist has begun to rewrite the story, not just of cloth, but also the much larger tale of how human beings developed and organised themselves, how towns and cities developed, how people began to travel, trade and to wage war on each other, and in doing so they are changing everything we used to believe about the history of humanity. These are textile archaeologists, people who devote their work to unravelling the secrets of ancient textiles, rather than discarding them as worthless, as used to happen.

One of them is Margarita Gleba and we went to the University of Padua in Italy to talk to her. Margarita is a scientist through and through – but one who is fascinated by ancient textiles and how they were made and used. She is at the top of her field and recognised globally for her knowledge and work on early textiles in the Mediterranean and Europe. And one of the lovely things about her is her joy in textiles – her knowledge and enthusiasm bubble out of her.

Margarita: I think, first of all, I see my role as bringing textiles onto kind of wider radar of people who generally don’t think about them. Until recently, it was always, regardless, some sort of very specialized kind of research done by primarily conservators, because they’re the ones who have to deal with this in a way, very problematic, inconvenient material. Because it’s fragile, it is difficult, it is messy, and mostly archaeologists, when they find textiles in the field, it creates more problems than anything else. And I’m happy to say that over the last 20, 30 years, I think we’ve moved on, and textile archaeology has become much more mainstream. It, is now acceptable that this material, like any other, like pottery, like metals, like glass you have to study as part of material record of past cultures. And it’s important, not to separate it, but see it as more holistically as part of these past cultures. They absolutely needed textiles and anything that had to do with fibrous materials, going back already as, as we’ve seen to Paleolithic and certainly in later periods, we cannot live without them. It’s a necessity for us. So we cannot ignore them in terms of looking at economies of the past, as social organization of the past, of identity.

JA: Welcome to Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles, my name is Jo Andrews, and I’m a handweaver interested in what textiles tell us about the story of humanity and in particular, what they have to say about the, often unrecorded, lives of those who make cloth and fabric. This time we are taking a trip back as far in time as science will allow us, to try to answer some of the most fundamental questions about textiles and human beings and Margarita will be our guide.

Before we start I should say that this episode is for Gabriel and Ethan Khamsi who are 10 and 8 and regular listeners. They specifically asked for more about insects and textiles. This episode does include some insect content – but it is about a lot more as well – I hope it interests you, and the rest of us as well. This is an exciting time to study ancient textiles because so little has been properly looked at in the past so there are lots of gaps in our knowledge, lots to be discovered, and who knows where this road may yet take us? Margarita herself came into the field by chance.

Margarita: So I actually started my education at the university in biology. And in the roundabout way, I took a class in art history, which started with ancient art history. And I became so fascinated and so interested in it that I decided to do also degree in art history. I was doing those two in parallel. And when I was finishing university, the time came to decide which direction to take. I was sure I wanted to move on with graduate education doing a PhD, but I didn’t know anything at what an art historian does. So my professor of ancient art suggested that I should go in an excavation. I tried that and I absolutely fell in love with the process of excavating and uncovering the past and the combination that it allowed me to do of natural sciences that I knew and was interested in and humanities. So that’s basically how I became an archaeologist. And when I was doing my master’s degree, I wanted to work on actual archaeological material, and the excavation director of the site where I was working at the time, gave me spindle whorls and loom weights to work with for my topic. And the more I started looking into that, the more fascinated I became with the fact that nobody was really interested in textile production in ancient Italy, even though it seemed to me like this was a fundamental part of economy, of religious aspects, of social aspects of all ancient societies, and particularly in ancient Italy, I would say. So, the more I got to understand how little there is, the more I wanted to study it. And so, I continued with that now for over 20 years, not only in Italy, but in other parts of the world. And I suspect that I will probably be studying textiles until the end of my life.

JA: Margarita’s parents are both scientists, but looking back she realises that there were some good textile traditions in her family:

Margarita: There were probably some nudges because on both of my family sides, my grandmothers were textile producers, my Lithuanian grandmother wove textiles. She produced linen in fairly traditional Lithuanian patterns. And in fact, a loom was standing in the room that I was sharing with her when I was a child. On my Ukrainian side, my grandmother was an excellent embroiderer. She also did sewing and all sorts of other textile-related activities, but what she was excellent at and what she loved to do in her spare time was beadwork and embroidery, traditional Carpathian embroidery. And I still have some of her works with me, which is a wonderful heirloom, I would say. That reminds me also the background, I suppose that I come from.

JA: But Margarita’s world today is one in which she is peering back into the far past rather than the recent past of her grandmothers, trying to answer questions such as how long have people been wearing clothes? Of course, fabrics and fur crumble to dust quite quickly and very little from deep time survives. But insects, in particular lice, have given scientists a way to understand how long clothing has been around:

Margarita: So, if you may know that there are two types of lice that the human body hosts the head lice and the body louse, the body louse lives on your body, and primarily in the clothing, in any kind of cover that covers the human body. Whereas the head louse, of course, is only in the hair, and they have these very separate environments in which they operate. But at some point, there was only one species. About a hundred thousand years ago, according to genetic analysis, these two separated, which indirectly gives us an idea that at that point people start covering their bodies with something. These would’ve not have been textiles, fabrics, these probably would’ve been skins. And we are talking probably more in the climates and during the time periods that earth was cooler, and so people needed to survive to wear something. So, these would’ve been animal pelt, skins something that we imagine in fact, prehistoric people wearing all the time.

JA: So here we have clothes of a sort, something to dress in and decorate, not textiles, but clothes, and after that we find a small tool that would quietly change the world – a tool that is still in use today, all these millennia later:

Margarita: So, as far as I recall, the earliest needles we have are about 60,000 years old, and they come from South Africa, but of course, we don’t know what they were used for, because of course, skins would’ve required sewing as well. Needles are older than textiles, absolutely, because you need needles to sew your skin garments. You also need needles to attach sometimes thousands and thousands of tiny beads to your leather garments. And we have evidence for that from some of the burials in Russia, for example, where there are beautiful decorations on what we presume were skin garments. You need somehow to sew them on. You need to make holes in the leather to be able to attach these little beads or, or other elements that you want to use for decoration. So needles are older than textiles. That said, of course, the limiting factor with needles is the material because if you want to make a very fine hole, you need to have a very fine needle. But to make an eye in the needle that’s fine enough is always a problem, particularly with materials like ivory and bone, which shatter very easily. So you also then need materials to create the needle. And those would’ve been always a little bit thick. They may have been used more as awls rather than needles. So making holes and then passing the thread directly using, for example, boar bristles. That’s one of the techniques that we know ethnographically, and that works very well also in leather making. It was still used in medieval times, as far as I know, for making shoes. But once people invent metals, that is a game changer, because you can make a very fine needle, you can cast the bronze, or later on, of course, they’ve become made out of iron and steel. But bronze ones are particularly common throughout a very long period of time. That’s when I think they start being used with textiles. And again, it is not only sewing things together, because if we look at the fashions, if we can call it that, of the Mediterranean cultures and Mesopotamian, they’re not tailored. They’re generally pieces of cloth that are woven to shape and arranged on the body with very minimal sewing. Even Roman tunic, for example, it would be woven to shape with sleeves, and then only the side seams would be quickly stitched together. So needles were not strictly speaking even necessary in some of these societies, but if we look at the Eurasian side, where we have horse riding cultures, which are believed to have invented things like trousers, that we all use a daily basis, and kaftans and tailored garments that we take for granted, those, of course, would’ve required quite a bit of tailoring and sewing. And we have already quite advanced types of stitching that we observe already in the Bronze Age finds from the Taklamacan Desert, where we have quite a lot of mummies preserving, full clothing. So needles, of course, are absolutely fundamental for human clothing, but they’re not directly connected to textiles.

JA: This means that the needle is older than the sword by several thousands of years. In fact, the humble needle is one of the oldest human tools in existence, much, much older than the invention of the wheel, the introduction of farming, or the use of the boat. Its impact on humanity seems just as great as these, but it has been much less written about or celebrated. We now have to wait several thousand years, dressed in our fur and leather, with beads attached with needles. But then comes one of the great game changers in human existence – the invention of string and thread. It’s impossible to say which humans first discovered that rolling dead plant stems along their thighs could create a strong twine, but it altered everyone’s lives and it still does today. Elizabeth Wayland Barber, the academic and author of Women’s Work, The First 20,000 Years says: “So powerful in fact is simple string in taming the world to human will and ingenuity that I suspect it to be the unseen weapon that allowed the human race to conquer the earth”. Margarita agrees:

Margarita: I think it was absolutely a revolution when people started doing that. First of all, if you think of all the purposes that string can be used for, from building, to making tools, those arrowheads made out of stone, they have to be attached to the wooden part somehow. Of course, you can use sinew, you can use unprocessed fibres, and so on, but if you have an actual nice thread or a rope or a cord, you can do it much better and it’s much stronger, and it will work much better for that. You can start creating two-dimensional objects, such as nets, which allow you to capture animals, to catch birds, to catch fish or simply use a cord for fishing, as we still do today, of course we use synthetic materials, but in the past, these would’ve been all made out of various plant fibres. So, from subsistence to building to personal adornment, a string would’ve revolutionized the way people carried on with their lives.

JA: We are still in the Stone Age when this happens but the evidence is clear that string began to become dress:

Margarita: So in concrete dates, we are talking 27 to 20,000 years ago, and our evidence consists of little figurines that are known in archaeology as Venus figurines. You may have heard of the famous Venus of Willendorf, which is a tiny figurine of a rather plump female figure that is currently in the Museum of Natural History in Vienna, in Austria. And she has kind of a net on her head. There are other figurines like the Lespugue Venus from France that has sort of a string skirt on her and others from Russia, from Ukraine, from other parts of the world that again, have string like elements depicted on them. They’re very stylized, but it’s very clear that all of them have something on their body that is very much string like. And the curious thing is that these seem to be not so much elements that protect the body, but rather highlight certain parts of the body. So they’re very much connected to the identity rather than simple physical protection that we think of textiles generally having. So these are probably the earliest indications that by that point in time, people know how to make string and how to combine it possibly with other elements into objects that they wear on their bodies.

JA: We haven’t quite arrived at the catwalk and couture but here’s the beginning of the road, where string and then textiles slowly start to replace skins.

Margarita: So 20,000 years ago, roughly speaking, people start adding to that repetoire string-like elements, whether they were for decoration first or already start using them as true fabrics. We don’t know, we don’t have yet the resolution archeologically of that kind of data. Nevertheless, by, I would say 10,000 BC probably fabrics are starting to be as important in some parts of the world as skins, certainly in the warmer climates in the Mediterranean, in the near East, in the Mesopotamian regions where we have a lot of, some of the earliest developments that, that we see in terms of domestication, in terms of technologies and so on. Probably we start getting already textiles, starting slowly replacing skins as the primary material for human clothing and lots of other types of uses.

JA: And the reason this happens is that textiles work much better than skins, especially in hot climates:

Margarita: And the earliest textiles we have are actually made out of plant fibres. First. They’re using whatever is available in the environment, tree bast, various kinds of grasses, possibly until little by little experimentation shows that certain varieties of flax are particularly suitable for making beautiful fibres that allow you to create very long, very strong, very fine threads that in their turn allow you to weave beautiful, thin, comfortable cloth that can be used, particularly in hotter climates. And it’s also then, if we think about it, by that point, human beings insist on covering their body. So, you need this cover. It’s a necessity on a par with food and shelter.

JA: A necessity maybe – but right from the beginning textiles have been something else as well – they have been carriers and expressions of who we are and this is what makes Margarita’s work interesting and exciting.

Margarita: It very quickly becomes part of people’s identity. And I think that we can take back already to the earliest strings that we see on these little Venus figurines. They’re not protecting the body from the elements. They are expressing their identity. And I think textiles still remain one of the primary carriers of our identity, whether individual, one, our, our sex, our gender, our ethnicity, our religion, our age, but also group identity. We belong to a certain village. We belong to a certain profession. We belong to a certain cast, we belong to a certain rank. All of these elements can be read as far as non-verbal communication in an instant by somebody who understands the language of textiles, the language of dress, because in the end, now, most of our dress is textiles. We still use a little bit of leather and skin. But around the world, if we look the majority of costumes and most of dress is textiles.

JA: It’s hard for archaeologists to get this kind of data from ancient textiles because often they are working with tiny fragments – but this is where ancient mosaics, frescos, and vases come in:

Margarita: Once people start showing themselves in paintings on vases, in sculpture, all of a sudden we have this entire new body of reference that allows us to see, yes, in ancient Egypt, they wear very different things than in ancient Mesopotamia or in ancient Greece, or in ancient Iberia. And we can take it all around the world. This is why a single glance, not only at the style of representation, but also at the dress that the people represented are wearing, can allow us to place any work of ancient art in a particular culture. Very often it is about the dress we can all imagine a Greek peplos or himation on a Greek statue when we, we go to a museum and we immediately recognize that as something belonging to ancient Greek culture. Same with later periods as well. So, I think this is something that goes back a very, very long time ago. What element of textile was important, is more difficult to say. But we certainly see in later periods that it’s both the type of fibre they use, the type of weave that they choose to, to combine their threads into the colours, the combination of colours, additional elements, the addition of beads or appliques, embroidery, the way the textiles are combined with each other. And also, the type of clothing: Is it something that’s arranged on the body and woven to shape and to use pins and belts and other kinds of elements to fix it on the body? Or is it tailored? So, all of these can create an infinite variety of expressions that we see. And then the question becomes, why do certain groups of people in certain periods of time choose this particular combination or the other? And these are very difficult questions, of course to answer, but very fun ones to explore as an archaeologist.

JA: The great problem for textile archaeologists is that the stuff doesn’t last very long, I wear out even my own clothes – so how does clothing that is thousands of years old survive?

Margarita: But there are certain circumstances certain conditions in the environment that can preserve textiles. This can be very hot climate, very arid climate. We see that, for example, in Egypt, or high elevations and dryness and heat in the Andes, for example, most of the pre-Colombian textiles survive that way in perfect conditions, almost. Freezing, we freeze our food to preserve it. It works the same way with textiles. So, the famous Otzi the Iceman is preserved that way. He hasn’t got true textiles, but he’s got twinings and he’s got leather. And in a way, he’s our first sort of point of reference for prehistoric Europe in terms of what people were wearing at the time.

JA: And water can also be helpful.

Margarita: So water logging can be one way of also textiles to survive. If textiles fall into water, and there is very little oxygen in it for the microorganism to thrive and to effectively rot away, to eat away the textile, textiles can survive for a very long time, especially if, in combination, they have also been charred, exposed to fire, in anoxic conditions. And this is the case, for example, with a lot of Neolithic Swiss textiles that survive in the lakes. Some of them date to 4,000 BC and little bit later as well. Italian lakes as well, the pile dwelling cultures that lived on the, on the Great Lakes in central Europe around the Alps, they produced fantastic textiles, and we’re lucky to have them because often in these villages that were made out of wood, you would have fire, fire would sweep through, everything would fall into the water and get silted over and preserved. Another famous case recently excavated late Bronze Age settlement of Must Farm in Cambridgeshire, where we have absolutely fantastic preservation of fibrous objects and textiles, of coarse wood, and many other things. There, there is a particularity, because depending on the acidity of water, you might have preservation either of plant materials or animal materials. So if at Must Farm, and in the Swiss Italian Neolithic and Bronze age settlements, we have mostly plant fibres, not because they didn’t use wool, it’s because wool does not survive in the alkaline water conditions. On the other hand, in places like Denmark or Ireland, where we have the famous bog bodies, some of which are fully dressed, we have primarily wool, skins and materials made out of proteins. And that’s because they are acidic and acids destroy celluloses that we have plant fibres, but they preserve proteins. In the 19th century, there was even an idea that certain cultures had a preference for wool rather than linen based on these differential preservations. But of course, now we know that it has nothing to do with the real preference, but that we have certain part of material record missing.

JA: And then finally there is a form of textile fossilisation.

Margarita: We have a very particular type of preservation that I deal with as my daily bread effectively. And that is mineralized textiles. They’re not quite fossils. Basically, in contact with iron or with copper-based alloys, such as bronze in particular, textiles may survive as they’re sometimes called pseudo-morphs, meaning they are effectively casts of textiles. They can be positive or negative casts that survive because metal salts slowly replace or accumulate on fibres. And I say slowly, but in reality it happens actually within weeks or months. So sometimes these textiles reflect the reality even more so than some of the organically preserved material, which often shrink, degrades, swell and lose their original configuration. We cannot tell the colours of mineralized textiles because they’ve been replaced by these metal salts, but they are perfect copies of actual weave. And we can, we can even identify the raw material using techniques like scanning electron microscopy because they form perfect casts of the fibre on the microscopic level. So I can tell whether the textile was made out of wool or out of flax or some other fibre simply by analysing a tiny bit of this textile.

JA: And that is where Margarita is happiest – looking down a microscope at tiny bits of ancient textiles that tell her amazing stories about who people were and what they wore:

Margarita: I love that. I love that because it allows you that sort of constant little discovery moment where you see, aha, this is made out of this material, and this is the kind of technique they used to produce this teeny bit. Often mineralized textiles are just few millimetres, few centimetres at most. So, they’re really tiny, precious windows into the past that unfortunately in the past were also removed because in conservation it was considered that you need to try to get to the sort of metal object and make it pristine. And so, you know, you would get, I don’t know, the 565th spearhead or sword, but the unique textile that was on it was not considered of interest, and so it was removed. Fortunately, this has changed. And now we have wonderful conservators who realize the importance of this data. And even if for the conservation purposes they have to remove these traces, they at least record them, or they call somebody like me to study it, to analyse it so that we actually have the record of it.

JA: The earliest fibres are linen, nettle and hemp. It took time for other fibres to be used and new tools and methods of processing them to be discovered.

Margarita: Wool and cotton come in much, much later, only well into the Neolithic. So, sixth, fifth, millennium BC is when we start getting really evidence that these fibres, short fibres become usable, and only much later, say third, second millennium BC where we have really written and archaeological evidence that these become more mainstream.

JA: And now we have fully fledged textile societies, where fabric is critical to the needs of the thousands of people who lived in the ancient towns and cities. It was to have a profound impact on how life was organised and what people did for thousands of years.

Margarita: What does it mean in terms of let’s say a city like Athens in Greece or a city like Tarquinia in Etruria functioning on a daily basis. Because all of these thousands of people, they need to be dressed. They need bedding, they need curtains, carpets, cushions, everything that we have inside our houses today, they already had. And most importantly, they’re moving around the Mediterranean at this point more than at any point in history. And they need sails, and they need lots of sails because those ships are not going anywhere without their engine and their engine are sails. So you need huge quantities of flax to be grown, to be then processed to produce the cloth for the sails. And this has to be organized at some point. Certainly, it appears that for most of this period, and probably all the way until the Industrial Revolution, domestic production, domestic cottage industry still is really the main mode of producing textiles. This can be enhanced very quickly. If there is a necessity, let’s say the city is going to war, we need lots of sails for our warships. Every household gets sort a directive to produce a certain quantity. We can think of it as sort of taxation, which we have also examples of in much later period in medieval times in Viking age, where the production of Vadmal, this particular kind of cloth, then basically every household was producing that to pay taxes. And then this cloth was used for sails, for any other kind of purposes that was needed by the, the organization, by the state whatever entity that was sort of unifying the society that we’re talking about. So certainly, I think the textiles were absolutely fundamental to the development of the cities, but we do not have direct evidence as possibly with some of the other industries, because it remained in the hands very much of household.

JA And because textile production was in the household, that brings us to the questions of who was doing this work?

Margarita: And of course, that means also women and women are very often invisible, both in the archaeological record and in terms of how we approach it, it’s only recently that we start really paying more attention to what was the role of women in ancient societies. Our written records are very much biased because they’re written whether we like it or not, by men. And they were not interested in showing this side of life apart from a very particular side of it. So we have half of humanity really involved in an industry that was probably the most time consuming of all types of production in absolute until really the Industrial Revolution. And that is actually what the Industrial Revolution does when it comes around. It is all about textile production. It is about making textile production more efficient, faster, producing more in better ways. And that’s when things finally change. When, this switches from being something that’s done on a household level, even more advanced household industry, even small workshops. But until that point, humanity produces textiles primarily at home. And that is always less visible than anything that we can find in terms of workshops or factories for other types of materials.

JA Margarita says the central role women play in producing textiles is implicit in her work:

Margarita: But if we look at iconography, if we look at for example, where we find textile tools in Iron Age, Italy, in archaic Italy in Etruria, practically every woman’s grave includes a spindle world. It’s to the point that in the past where osteological determination, of the sex of the skeletal remains was not done, or in cases where it’s not possible because the bones are too degraded, or we have a cremation burial, the sex of the individual was assigned on the basis of the presence of textile tools. There are exceptions, but there’s so few that they prove the rule. In a way, it’s not the case maybe in all of the societies, but if we look also at iconography, who is depicted by the loom, it’s usually women. At the point when production becomes much more industrialized, you start seeing men coming in, and this is the case, possibly in medieval times, we will look at guilds, right? The Italian famous guild system for production of a variety of very high-quality textiles. Then of course, you start getting men involved. And this is something we see also in the ethnographic examples of other types of production, pottery even food production, who are the most famous chefs today? They’re mainly men. And yet it is women who are primarily associated with cooking on the household level. And it’s, it’s sort of a funny dichotomy.

JA: She also cautions against making wholesale assumptions, as she believes that such was the need at times whole communities would work together.

Margarita: For example, yes, we know that women were spinning and weaving, but who was tending the flocks? Traditionally it usually was the men because it was a dangerous thing to do. If you’re going out into the mountains, they are wolves, they are brigands. There are all sorts of things going on that women usually stayed at home and they had to look after the household, look after the children. Traditionally, that was the case. So sheep tending, sheep shearing probably was primarily done by men, and we had to remember that. Same possibly with production of flax, where entire communities would have to come together to do that. Spinning, it’s an activity that traditionally is associated with women, yes, but spinning is also the bottleneck of textile production. And therefore, when you need a lot of thread, everybody who’s capable of doing it will be doing it. Again we have historical and ethnographic examples of that where old and young men, women, whoever is available, everybody spins to produce enough thread for the weavers to carry out their work when they have sufficient amount of thread ready. But in terms of what the sort of the society wants to project, of course, it is the women that are the textile makers, just like the women are the carers, the cooks and, and so on. If we look around today, there is not such strong differentiation anymore, and yet the stereotypes persist. So, we need to be sometimes a little bit careful when we project the stereotypes, also in the past. There were stereotypes created by the past for us to sometimes maybe too simplistically take them and organize things into convenient little boxes. It, it is much simpler to divide, like, men do this, women do this. But it was as today much more complicated, much more nuanced than it is. So there’s certain tendencies and the tendency is that yes, women are primarily weavers and spinners and makers of textile, but it’s not a hundred percent.

JA: But we will leave Margarita with her microscope, and her knowledge that whenever she finds something with textiles on it, or as part of it, it has something to tell her:

Margarita: It’s also part of really, the story of the object. Why is the textile on it? What does it tell us about the past? But if it comes from burial or some other context. It means that there was a textile present. What was it doing there? What was its meaning? What was its function? Something that in the past would’ve been ignored. Now we can get a lot of information from these teensy little pieces that survive.

JA: I love the fact that these tiny unregarded pieces of fabric that have lain in the dust for centuries have the capacity to stir ghosts of long ago, to bring alive people who made beautiful and useful fabrics, who cared about what they made and what they wore. There is something breathtaking about being to see work that is tens of thousands of years old and understand how the woman who made it, designed her project and carried it out, to follow the thought processes of someone who came so long before us.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Haptic and Hue, and a huge thank you to Margarita Gleba of the University of Padova for sharing some of her knowledge and wisdom. If you would like to see pictures of some of the figures and textiles Margarita talked about, or read a full script of this podcast, you can find them on Haptic and Hue’s website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews, and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a member of the new Friends of Haptic & Hue, which costs £50 a year or £5 a month. This keeps the podcast truly independent and free from sponsorship and advertising. If you’d like to find out more, it’s on the website at www.hapticandhue.com/friends.

Meanwhile with thanks to Shannon Nottestad a listener in Portland, Oregon, I will leave you this time with a poem called Instruction by the American poet Hazel Hall, who made her living in the 19th and early 20th centuries using her needle:

My hands that guide a needle

In their turn are led

Relentlessly and deftly

As a needle leads a thread.

Other hands are teaching

My needle; when I sew

I feel the cool, thin fingers

Of hands I do not know.

They urge my needle onward,

They smooth my seams, until

The worry of my stitches

Smothers in their skill.

All the tired women,

Who sewed their lives away,

Speak in my deft fingers

As I sew to-day.