Stitches By Candlelight

Mary, Queen of Scots in Fabrics and Embroidery

Episode #35

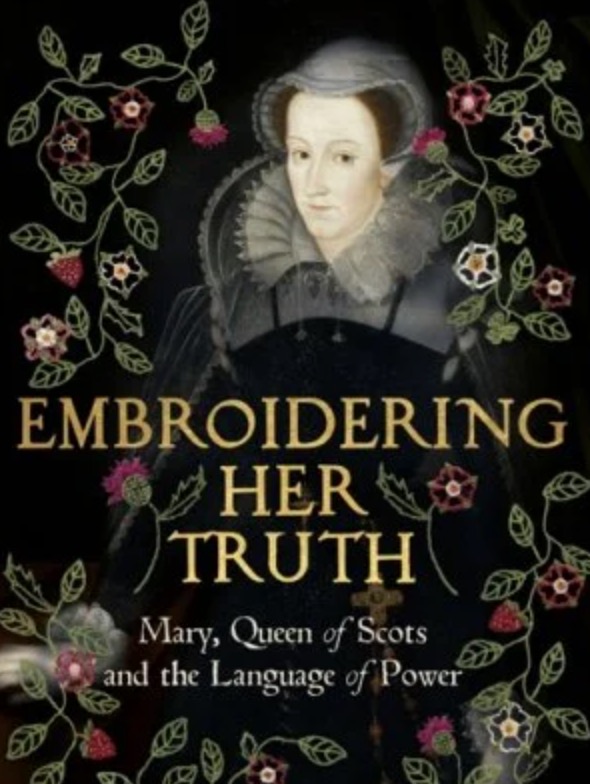

This episode celebrates Haptic & Hue’s pick as its book of year for 2022 which is Clare Hunter’s Embroidering Her Truth, Mary Queen of Scots and the Language of Power. In this special end-of-year episode, Jo talks at length to Clare about her research and what it told her about Mary.

For the first time, Clare looks at Mary with textile eyes. She sets Mary in context both as a consumer of elite textiles and also as an embroiderer during her long captivity. At her death, Mary left over 300 embroideries, many of which can still be seen, both in Scotland and England. These were the only form of communication left to her and she used them to tell her own story in the way she chose. They give us an insight into her state of mind and the messages she was trying to convey to the outside world.

Clare Hunter has her own website – where you can find out more about her practice as a community stitcher, banner maker and curator, as well as a wonderful writer. https://www.sewingmatters.co.uk/about.html

You can also find her on Instagram @sewingmatters

Both the hardback version of her book Embroidering Her Truth and the paperback edition (which is due out early in the New Year) can be found in the Haptic & Hue UK Bookshop. Sadly it has not been published in the US (yet), but it can be found here, and in the rest of the world, at good independent booksellers online and real concrete ones! Please note that if you buy the book through the H&H bookshop, Haptic & Hue gets a small commission at no extra cost to you.

If you would like to see Mary’s surviving embroideries either online or in person, here are the places to look:

The Victoria and Albert Museum, London: Online. I don’t know if they currently have any on display you would need to check with them before visiting.

Holyrood House in Edinburgh – where you can see the ginger cat with the little mouse under its paw – that Clare talks about and some other work as well.

Oxburgh Hall in Norfolk – which is run by the National Trust has the Marian Hangings on display, which were stitched by Mary and Bess of Hardwick during Mary’s imprisonment.

Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire holds an extensive embroidery collection, one of the largest in Europe, including a number of pieces by Mary.

You can follow Haptic & Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic & Hue name.

Clare Hunter

Embroidering Her Truth

Mary, Queen of Scots circa 1559

The Ginger Cat plays with the Mouse

Mary’s Cipher

A Bird of Prey kills a small songbird

Hammerhead Shark Embroidered by Mary

Prison Embroidery by Mary

Prison Embroidery Bearing Marian symbols

Stitches by Candlelight

Jo: This episode is a bit different from the others. It’s a way of waving goodbye to 2022 with a great book. It’s a special extended interview with the author Clare Hunter, who has published her wonderful reinterpretation of the story of Mary Queen of Scots this year. It’s called Embroidering Her Truth, Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Language of Power. I keep a reasonably close eye on new books about textiles, mainly because I’m an avid reader myself and for my money, this book stood head and shoulders above the others, not just for Clare’s very human approach and easy writing style, but because of the way she turns up so much fresh information in a story we think we know so well. If you haven’t already got it on your holiday reading list, ask for it now. It’s just the thing for the Northern Hemisphere’s long winter nights.

Welcome to Haptic and Hue. My name is Jo Andrews and I’m a hand weaver interested in what textiles tell us about the story of humanity and in particular what they have to say about the lives of those who make cloth and fabric. Clare does a great job in this book of looking in a different way at Mary and the women of her time. She shows us how in an age before widespread literacy, people communicated through their clothes and the colours they wore and that these could be read and understood just as we can read books and magazines. This is Clare’s second book, her first: Threads of Life, The History of the World Through The Eye of a Needle was for me one of those great gateway books that helps you really understand why textiles are so important to the story of humanity. This time Clare has taken one of the most written about women in history and discovered something fresh to say, despite the clichés that surround Mary’s life and her story.

Clare: Well, I think obviously for me being Scottish that Mary Queen of Scots was a figure in my life from my childhood and I used to lust after those little dolls that you saw behind cellophane boxes, which would always have Mary Queen of Scots in her kind of iconic black velvet with her white veiled trailing. You know, I could never afford one, but I desperately wanted one. And then when I was writing Threads of Life, then of course I did feature Mary in the chapter on Power as the central figure. And in the research I did for that chapter, I just became fascinated by how much material there was that hadn’t been explored, particularly in all her inventories, the treasurer’s accounts, which uh, basically were her kind of Amazon purchase history for the years during her reign. And I just thought there’s something here to be said, both about Mary and about women’s culture in the 16th century.

Jo: And do you think that women’s culture in the 16th century is something that is really completely new ground? It’s something that we really haven’t looked at or are researchers beginning to start to look at this?

Clare: Yes, I think there’s been a groundswell both from a feminist angle obviously of people looking at the lives of women and the neglect of women’s culture. And also, now increasingly there is an interest in the material culture of women. And I suppose that’s the angle I’m coming at it from, to look at Mary’s life through the prism of the textiles that she displayed gifted, bequeathed u and indeed created and what that said about forms of women’s agency, which maybe hadn’t been looked at or examined.

Jo: I always feel this is astonishing and every time I consider this, I think this is completely amazing. This is a whole section and side of history that we have simply left out and almost always changes everything. Does it seem like that to you when you begin to reconsider these stories and these histories in the light of textiles and material culture?

Clare: Well, yes. I think it’s maybe not surprising that it’s been overlooked, partly because through the centuries the main chroniclers and historians were men and they had little interest in, as I say, women’s culture or indeed not that much interest in material culture beyond architecture and art. And so other aspects of material cultures were neglected. And I think that with more women coming into the fray of historical research as curators at museums and as writers and being published, then there’s increasing interest and capacity to unpick what the material culture of different times tells us about, particularly the women who were living through them.

Jo: And could you set Mary in her time for us? We think we know her, we think we’re familiar with her story and her image, but what did it mean to be a queen at that time, particularly one who was brought up at the French court?

Clare: Well, we’re talking about a time in the late Renaissance when the power of the monarchy was becoming more uncertain because it was a huge time of change, religious, social and cultural. And basically, in trying to forge better and stronger political allegiances, princesses were being bartered for peace. And Mary was a queen of higher value and she became a queen when she was just a baby and she was a political prize. And you can see in the French treasury accounts how much they invested in her presence at the French court by the kinds of fabrics they were purchasing for her small girl wardrobe, the damasks and the velvets and the cloth of golds and the damasks you know, embroidered with gold and silver threads. And that investment was, as I say, a political investment to show Mary off for the worth she had in terms of politics of the time.

Jo: And was it a privilege for her to be at the French court in a sense? Was this a court that was particularly invested in textiles?

Clare: Well, it was particularly invested in material culture and basically had, you know, imported artisans from different parts of particularly Europe to come and create a new visual splendour and magnificence that would express power and capacity and prosperity as did other monarchs and other countries at the time. And Mary leaving a Scotland, which did have aspects of renaissance glory that her father and her grandfather had introduced to the country, but it had none of the largesse of the French chateaux, none of the sumptuousness it had invested in. So for her it was a kind of luxury of a material world that she maybe hadn’t encountered on such a vast scale.

Jo: And in the book, you talk, and I love this, how the textiles and clothes worn at court became, and I’m quoting here, became declarations not just of who they were but how they wish to be regarded. You also delightfully say that the skilled artist of the court could transmit emotion through imagery. Can you explain that a bit more?

Clare: We’re talking about a time when the visual culture was paramount and textiles were read like a book in terms that every interior was festooned in textiles. And not only that, because courts moved from place to place and textiles were portable, they were also the trappings of power as it went through nations or when there were ceremonial events, et cetera. And we’re talking about a whole vast array of textiles from tapestries on the walls to the bed hangings to clothes themselves to embroidered carpets, table runners, because there wasn’t much in the way of furniture in those days it was textiles that were not just the main form of decoration, but the main form of layering meaning onto court surface with messages of power, lineage, erudition and allegiance.

Jo: And you also talk about these kings and queens, princes and nobility transmitting public charisma through the textiles. Can you tell me a bit about that?

Clare: The sumptuary laws at the time which were originally designed to control trade then became more and more interested in controlling the hierarchy of social status and as part of that, it was only the elite and in particular the monarchy who were allowed to wear the most beautiful of fabrics and most expensive fabrics, allowed to have embroidery to wear lace. There were all sorts of laws pertaining to what people could wear, and also a time of great moves forward in textile production and the technology of textile production. So, you didn’t just have velvet, for instance, you had all different kinds of velvet, some that were under woven in silver and gold, some which were voided to allow patterns to become more prominent under light and shadow, all sorts of different ways that people manipulated fabric to give it in itself a presence, particularly under candlelight. So that play of light on fabric amplified the glittering presence of a court

Jo: And so was this idea of presenting yourself through textiles and then through the pictures, was that a new idea? Because we have this really strong idea of what Mary looked like and how she dressed, but if I was to say to you, William, the Conqueror, we would have no idea of what he looked like or what he was dressed in. So, was this a new idea of her time?

Clare: New in terms of its variance and its layering of meaning. Deep red was often the colour of people in power. Now that’s simply because of the expense of the dyes that people had access to. And those colours were the most luxurious colours to wear. And there’d always been rich and embroidered fabrics, but not to the level that we see in the renaissance. And that again is because the kinds of materials, the kinds of threads and indeed the kinds of needles that people had access to by the 16th century allowed there to be a much greater finesse of detail in what was shown on clothes and on interior textiles.

Jo: And you talk about deep red being if you like, the colour of royalty, but even the colours, even if they weren’t red, colours seemed to hold a very specific meaning. And it seems as though every dress Mary wore would be, you say, read like a book. Can you just explain a bit more about the dresses she wore in France, which I think were often black and white, weren’t they?

Clare: Well, not in France, and France was during her girlhood, her dresses were all sorts of colours. I mean colour in itself is really interesting in terms it was symbolic and green signified rebirth, yellow stood for hope and silver for purity. And red itself being the colour of blood was the symbol of strength, and people wore it as an aid to good health. And there were also the pairings of colours. So, for instance, white and tawny, which was an orange-brown, indicated patience, red and purple stood for strength and blue and violet stood for loyalty and love. And people would’ve been able to read all those singular colours and the pairings of colours and understand, you know, the message behind them. Mary in the French court was dressed as a girl, as I say, in a range of colours, but when she was widowed at the age of 18, she was then painted in what was the jewel white, the French colour of mourning for royalty. And then when she came back to Scotland, as far as we were aware, and her treasurers’ accounts seem to bear this out, for at least the first years of her reign she was generally as you see in black.

Jo: And what do you think it was like for her on a personal level to leave glittering Paris and to come back to Scotland?

Clare: Well, I think for Mary both the physical experience of leaving the French court and also the emotional experience of leaving what was really the first family that she had been around and been nurtured by. Because when she came back to Scotland, she was newly orphaned. She was newly widowed. She had spent the last 13 years supported by her Guise grandparents and uncles and aunts and basically under the protection of the very powerful Valois dynasty. But when she arrived back in Scotland, there was no one of her status there. And also, her religion, her Catholicism was just newly prescribed in that Scotland was newly under the Reformation, and the Reformation had happened. It was a Protestant country, not just Protestant, it was a Calvinistic Protestantism. And with that came a censure against decoration, embellishment, material sensuality if you like. They were seen as a sense of vanity. And you have John Knox who is the spiritual leader of that reformation, Scotland being askance at Mary and her entourage, who were mainly young girls, the four Marys that we know of skipping alone in the house at night. And basically, as he describes it, having far too much ‘joyestie’. So, she comes back to this court, which has been in its culture, very male-dominated, a martial culture in the main, and she comes as a young girl with a sense of merriment and gaiety and basically finds a much sterner climate in which she has to rule her country.

Jo: And as Queen of Scotland, it seems to me that her clothes and her joyety came under absolutely huge scrutiny. How did she change the way she dressed and how did she use her textiles during this time?

Clare: One of the things she did quite early on her was to begin to remove from the royal wardrobe clothes that had belonged to her mother, who had died just before Mary had returned to Scotland. And Mary De Guise herself was plagued by the reformists who basically wanted her deposed and so had struggled to try and contain peaceful and religious terms in the country. And when Mary came back that kind of re-apportioning of her mother’s clothes to herself was a statement of her restating the power of her mother. But another lovely example I think is at Mary’s first parliament in 1563, then she dressed herself and her entourage in the most sumptuous of clothes with long trains. And Mary was dressed in purple velvet and taffeta, violet taffeta, and they were sparkling in jewels. And you can just imagine what was this posse of, Queen Mary was five foot 10 inches tall. She was a very tall woman who already had stature, and against a Scottish population, she would’ve seemed extremely tall. That sight of her posse of young girls, her ladies strutting down Princes Street in Edinburgh Mary in her purple velvet and her ladies equally sumptuously, dressed sparkling as I say in their jewels, must have been an extraordinary sight to the population. And basically of course it was a statement of female power.

Jo: And how did that go down?

Clare: Well with John Knox? Not at all, he called it “the stinking pride of women as was seen that day in parliament”, he was quoted to have said.

Jo: I think we can safely say that John Knox wasn’t a feminist as in “the monstrous regiment”.

Clare: That’s right, absolutely. And, of course, Mary had to contend with that. And at the time there was a major debate that was going on throughout Europe about whether women, the Querelle de Dames it was called, about whether women had any capacity at all to rule

Jo: Looking south of the border at the other woman who was showing whether or not women had the capacity to rule, her cousin Elizabeth when we look at the portraits of these two women, Mary appears to be much more austerely dressed and Elizabeth always appears to be much more colourfully and much more grandly dressed. Is that a coincidence or were they trying to use their clothes to say different things?

Clare: Oh, definitely trying to use their clothes to say different things. I mean in portraits of the day in the 16th century, they were deliberate statements of really what the idea of majesty was. So, you know in the 16th century when portraits were painted, then generally there would be different artists working on the same portrait. And the painter who painted the facial features of a sitter would be paid less than the painter who actually painted the fabric the sitter was wearing because it was the fabric that told the world about power and prosperity, not the facial features, which is absolutely astonishing and really interesting. So basically, in Mary, I mean there are only a few portraits of her painted in her adult life and she chose to have herself painted because as I say, these were deliberate presentations thought through and done with an eye to the outer world, particularly other monarchs and what kind of person you would appear to be and what kind of as the body politic of your country, how it would actually show your own nation. And so Mary chose generally to be painted, wearing black, her iconic black velvet dress with the flowing white veil. Now, as I said about colours, then this was a deliberate contrast in terms of what she was showing was constancy, and black was also the colour of statesmanhood. So, she was showing constancy, governance and also through the white veil, innocence and piety, because to Mary, particularly in captivity, her Catholicism and her possible martyrdom was the thing that she wanted to point up to the outside world. Liz however, is dressed in a concoction of fabric, she’s festooned in ribbons and bows and jewels and expansive in huge ruffs, gigantic sleeves, big skirts, all that because she used her clothing and the clothing that was shown in her portraits as material armour as a defence for herself, who always had had insecurity in terms of her right to rule. She had been written out of the succession by her father at one point, and although she was reinstated, she was never really sure that that would still stand. And, of course, in Catholic Europe, her succession as queen was not accepted, was not acknowledged because she was a Protestant. And so, she was in an insecure position and she used her clothes and her portrait to basically show an idea of majesty that was stable. As I say, that was prosperous and that was uh, outward-looking and explorative

Jo: In the book, you are not just writing about Mary’s clothes, you are also writing very much about her embroidery. And I think in Mary’s time, embroidery had a very different place in women’s lives. Can you expand on that a bit?

Clare: In the 16th century, embroidery began to move out of the ecclesiastical quarters of monasteries and nunneries and fall into more secular hands in terms of the courts. Now it had always been there in the courts in terms of the workshops of professional embroideries, but actually as these new threads and fabrics and particularly needles became accessible, then elite women were able to take up embroidery as another form of writing, and they saw it as a form of writing. And basically, they used their own needlework both as a way to stitch messages that could assert their own worth in terms of relationships and their knowledge, but also, they used it as a way to gift handmade personal items to others as a form of diplomacy and as a form of garnering support.

Jo: Can you give some examples of that?

Clare: Well, a nice example I think is Elizabeth the First and, well, as I said, she had lost her place in succession but then regained it. But as a girl, she embroidered for her father Henry, the Eighth and his then-wife, uh, Catherine Parr, books which had embroidered covers. Now, these were done in a very thoughtful way. She had an interlaced patterning, which showed the interconnectedness between her and Henry and Catherine. She had pansies for thoughts, sometimes she sported the Tudor Rose to show again her connection to that Tudor lineage. And what she was really trying to display there was the continuity of the capacity and uh, the finesse of women through the Tudor dynasty, connected to others who’d show that she had these queenly accomplishments. Because as I said, embroidery was an accomplishment of the elite. So, to show that she had these queenly accomplishments, but also in the time that it would’ve taken her, she used very intricate forms of needlework, again purposefully in order to show that she had given her labour for love of them. And they would be able to read those different things, not just the imagery and what symbolically it meant, but also the act of sewing was a metaphor in itself for the time and patience that she was wanting to spend on showing her love for her father and his then-wife.

Jo: Do you think we’ve lost something in the modern world because we can’t read textiles and stitch in the same way as they could at the time of the Renaissance?

Clare: Yes. I mean obviously, we have in our century placed it in a much more reduced form. So, we happily use emojis without thinking of them as a shorthand, visual images for emotional things that we want to see. But actually, they are the same thing. It’s in the same territory. And I think increasingly people are turning back to the handwrought as a way to make more potent the things that they give to others or the things that they leave behind for others. So, I think we have seen a, a new upsurge of interest because of the kind of age we live in and because of people not wanting to be reduced to an algorithm then that kind of personal way of actually speaking of who we are. And I think the wonderful thing about embroidery is that actually the sense of it, the essence of it, of us who make it still lingers in the cloth itself, um, you know, it holds the rhythm of our stitches. It holds the tension of our threads. And so, it does speak of us in a particular kind of way. And I think that’s very beguiling for people increasingly, as I say, as they feel that their individual persona is becoming blocked out by our social media world.

Jo: Did Mary’s embroidery do that for you?

Clare: I had seen Mary’s embroidery but behind glass before, and although I found it really, really fascinating, it didn’t really speak to me. But however, I went to the Palace of Holyrood House and the curators there took out, they’ve got two small embroideries of Mary’s and they took them out of their cases. And although I wasn’t allowed to touch them, I was able to see them close up. And I did find that really, really illuminating because when you look at Mary’s embroidery close up, then actually she’s not a fantastic needlewoman. She was never interested in the stitching. She’s really only interested in the message it conveys. And her stitching in itself is, is quite unsettled. You imagine her in captivity when she did most of her embroidery. She did embroider in Scotland, but we’ve got very little information about that. But the embroidery of which she did a lot in captivity, basically you can see it as unsettled work, it kind of runs along very evenly for a while and then her settles become, her stitch has become more unsettled and then, then you can feel her calming down. You can just imagine the thoughts that were going through her head as she was stitching. And that unsettled needlework points to the moments of calm, as I say, or the moments of agitation. The one that I saw was a cat, an embroidery of a cat, as a monogram piece. And that one piece of the cat is really interesting because it features a ginger cat with a little kind of stolid mouse running by its paw, and the image of the cat, that was taken from a book of woodcuts at the time, black and white woodcuts. So, Mary had obviously purposefully coloured her cat ginger to personify Queen Elizabeth, who was of course known to be red-haired, and she had inserted, which wasn’t in the original woodcut, the little mice as personifying herself. And tellingly the cat’s paw is very firmly placed over the mouse’s tail holding it down. So, it’s actually a little image of Mary’s sense of defencelessness in captivity.

Jo: And what happens to Mary’s embroidery and her clothes off to her death? Do we know anything about that?

Clare: Well, we know that a lot of her clothes in the royal wardrobe in Edinburgh were sold off, and her half-brother James Murray, who became Regent, was in need of funds to fund what became the Civil War after Mary was taken into captivity, between the Marian party who were the supporters of Mary, and the King’s party who was supporters of her son, who was then just a child, who became James the Sixth of Scotland in the First of England. Others were bequeathed. So, Mary in her last will then bequeathed some of her embroideries. She left over 300 unfinished embroideries or mostly unfinished embroideries when she died, bequeathed to members of her own household. She had also given some as gifts in other times to both her ladies in waiting, to her four Marys, to female friends that she’d made at the Scottish Court, et cetera. And we are very lucky because a number of embroideries that she made when in captivity in the company of Bess of Hardwick, who was the wife of her guardian for a long time, the Earl of Shrewsbury, then those still survive. So, a lot are in Oxburgh Hall in Norfolk. There are three large panels and a single valence which are crowded with embroideries, over 30 of which are verified as Mary’s because they bear her monogram or a thistle or a Scottish word for something that she’s entitled to. And then there are also two cushions at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire, which of course Bess of Hardwick was the architect of, and the V and A also has some on display and the parts of Holyrood House in Edinburgh has two little ones. So we can go and see them, which I’d recommend, it’s well worth doing.

Jo: Thank you. I think this book was your lockdown project. How difficult was it to research it?

Clare: Well, you can imagine Jo, how difficult that was to be doing historical research when all the libraries, the archives, the stately homes that might have seen her pass, castles, museums, et cetera. Luckily, I had done an MA in historical research at the University of Stirling with the theme of Mary’s textiles as its subject. And so, I had visited a number of places, thank goodness beforehand. The online digitalization was also really, really essential in order to be able to write the book. The difficulty about that is that when you actually look at, you know, things like the state papers, then the font is very small. So, you have to zoom up per page and zoom down again when you turn the page. And as each volume has like 700 pages, it’s a very, very, very tedious job because I was searching for the nuggets that had been overlooked and I was searching for things about needlework or embroidery or textiles or clothes that maybe male historians or male chronicles of earlier times hadn’t found interesting. And so I was looking into the darkest corners of these primary papers and so it was very, very difficult. The other thing I think that was hard is that, as I say, her contemporary chroniclers and historians were men. And so the books that were written at that time, the reports that were made at that time about Mary took no interest in her clothes or the interior decoration. It was not part of the things that they were interested in. So apart from John Knox, we’ve got very little allusion to anything Mary was actually embroidering or wearing or displaying. So that’s just again, an example of how women’s history can get erased.

Jo: Last question. We often end episodes with a poem or a piece of writing and I wondered if there was any particular poem or piece of writing that you had come across about Mary or relating to textiles that you would like to share.

Clare: Not related to textiles, but it is about Mary and I just signed up very poignant. It’s very just a short court and it’s from the French poet Pierre De Ronsard, who had basically inculcated in Mary a love of poetry. And Mary did write a lot of poetry herself and he wrote it after she had been executed in 1587. And he was very grieved when he heard the news of her death and he said, ah, Kingdom of Scotland. I think your days are now shorter than they were and your night’s longer since you have lost that princess who was your light. Isn’t that lovely? And in the tragic life of Mary, which was a very tragic life, then those words of Ronsard at least show her as a light.

Jo: I think she had a bit of fun.

Clare: Oh, she did have a bit of fun. Definitely. She was a merry person at heart, I think. Mary

Jo: Thank you to Claire Hunter, author of Embroidering Her Truth, Mary Queen of Scots and The Language of Power. Her book can be found in the Haptic & Hue UK bookshop. And if you live elsewhere, it can be bought from any good online bookseller. This episode was presented by me. Jo Andrews. Haptic & Hue’s editor and producer is Bill Taylor. If you would like to read the script of this episode or see details of where to find Mary’s embroideries head over to Haptic and Hue’s website at www.hapticandhu.com/listen. We’ll be back with another episode in early January and we’ll also be launching a new way to support this podcast and access more from our textile travels. If you’d like to find out about Friends of Haptic and Hue, it’s on our website under the New Friends tab. We’ll also shortly be sending out more details to all our subscribers. Meanwhile, this comes to wish you all are very happy, end-of-year celebration wherever you are and however you do it and above all: thank you for listening.