Sewing, mending, knitting and all the fibre skills are seen as ‘Women’s Work’ in Western cultures. Why is this? We hear from men who were taught to sew and knit in wartime, in prison or in isolation, and we talk to men who freely choose to stitch, knit and spin as a hobby. What are the barriers men face if they take up these skills and what does the world lose if they don’t? This episode looks not just at the gender divide of the West but also thinks about the fabric traditions of Africa where men are deeply involved in textile production.

This episode would not have been made without the contributions of:

Eric Bacon, who lives in Somerset.

Joe Sullins, who weaves, spins, knits, and does needlepoint. You can find him on Ravelry as Joe Sullins, and on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/joesullins/

Precious Lovell is Associate Professor of Fashion and Design at Moore College of Art and Design in Philadelphia. She has her own website which features some of her amazing making, which you can find at: https://www.preciousdlovell.com/

Fine Cell Work which does fantastic work with male and female prisoners in the UK is at https://finecellwork.co.uk/ Its Christmas sale is on at present – be warned, it is all covetable.

My thanks too, to the prisoners Yusef and Tony who write so movingly about their experiences with Fine Cell Work, and to my friends Bill and Jamie who took their parts.

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name. You can see more of my work and that of other makers there or on the website.

And if you’ve got a great idea for Series Two (coming in the New Year!) then drop me a line via the website.

Have fun and enjoy your own making practice or just listening to the chatter of cloth!

Joe Sullins

Joe’s lace knitting

Joe’s Needlepoint

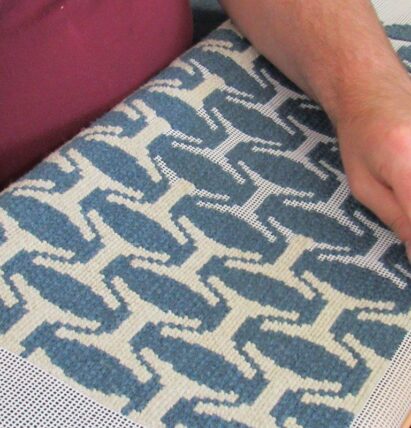

Weaving by Joe Sullins

Precious Lovell

Prison Stitching for Fine Cell Work

Stitching in Prison

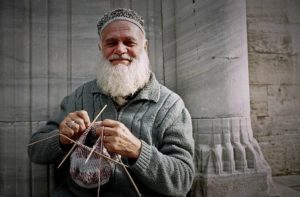

Sailors Knitting

Sewing on board ship

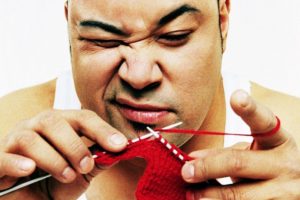

Complex Knitting

Embroidery

Knitting

Script

Making Men

I’d like you to meet Eric. He lives in Somerset, in the west country of Britain, He can knit, mend and darn and he’s also been a cross-stitcher and a sewer. He has made his own fitted sheets and pillowcases. These days he makes teddy bears for refugees and also knits squares for blankets to be donated to charity. He is 97. His journey as a maker started in 1942 when he was conscripted into the Navy at the height of the Second World War:

I had to learn how to sew and darn and launder. You’ve got to remember everything was by hand in those days.

What else could you do? You had no option. You just had to do it.

Well, if you didn’t, you soon had a leading hand on your neck telling you, you were filthy and if you don’t do it we will scrub you down.

After the war, Eric came home, married, and had children – and unusually for a man of his generation he always did the ironing – but he gave up the sewing and mending skills he’d been forced to learn onboard ship until something happened later in his life which led him back to cloth.

Welcome to Haptic and Hue’s first series of podcasts, which looks at textiles of all kinds down the centuries and thinks about the role they play in our lives. I’m Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver and a broadcaster. Haptic means the feel of something and Hue describes the pure spectrum colours.

Since this series of podcasts started over 250 people have subscribed to the newsletter so that they can get the podcasts directly in their in-box and stay up to date with what we are doing. Thank you to each and every one of you. For this episode I counted up every subscriber and judging by names only, its clear the overwhelming majority of you are women, in fact there are only three brave men amongst you, and, it seems to me this is not unusual. I expected this. All of the guild meetings over the years I have been to have been predominantly attended by women.

And that’s what this episode is about. It looks at why in industrialised northern societies, in Europe and North America and Australia and New Zealand it is almost exclusively women who learn the skills and crafts of soft materials, and work hard to conserve them, seeing value and pleasure in them, whereas many men seem close to frightened of them, almost as if their masculinity will evaporate if they pick up a knitting needle or sit down at a sewing machine.

In another life I ran gender workshops for charities and commercial organisations. To break the ice and to show how pervasive these stereotypes are I would ask everyone there to name one thing that they did that was typical for their gender and one thing they wished they could do that was outside traditional gender roles. It always amazed me the number of times men came back and said they wished they had taken up knitting or embroidery.

They could sense the joy this gave their mothers, wives, sisters and daughters and yet because they were men they felt this was barred to them.

As I made this episode and talked to men who do work with textiles, one theme that came through strongly was that more men than you think sew, crochet, weave and knit, but many of them do it almost covertly, unless there been a disaster in their lives that breaks through the constraints.

And this is where Eric is important. He was forced to learn these skills in the Navy, left them to one side afterwards and then something happened:

So, the next time that sewing came into being, as it were, was in 1992 in March, when I had a stroke, which left me unable to use my hands. And the only way I could get them working was sewing again. And that’s when I took to sewing fitted sheets and a pillowcase for two. And when I done that, my wife taught me to how to knit. And when I came to a tricky part I passed it over and she did it.

Well, I wouldn’t say working with them and trying to get the feel of a needle and things like that was enjoyment it was something I had to do to get the use back into my fingers.

Eric is a good knitter and sewer, he’s a member of a knit and natter group, but he is clear this is something he does – not because he gets enjoyment from it, but because he has to, to keep his hands working.

Well, it’s helped me at various times my life. I mean, it was just accident in life, its never been a hobby as such. Well, what else am I going to do? And nothing on television I can read. And there’s not much else is there.

And he doesn’t have any truck with the idea that other men might think this was odd.

Well, but then you got, yeah. Well, don’t start me off about men.

I haven’t a lot of times for a lot of men.

One organisation that does have a lot of time for men, is Fine Cell Work in the UK. It’s a charity that teaches mainly male prisoners to cross stitch and embroider. Their work is skilled and exceptionally beautiful. I’ve posted pictures of their work on the Haptic and Hue website. Fine Cell Work demands high standards from the men, it teaches them new skills and sells their work to generate income for them and their families.

I wanted to talk to one of those they have trained for this episode, but British prisons are currently on strict lockdown with postal service as the only method of communication. It isn’t easy for the charity to get supplies in and out of jails at present, let alone arrange for a prisoner to do an interview.

But we do have written accounts from prisoners and it’s clear that apart from having something to do while spending incredibly long periods in their cells they find value and enjoyment in the work and they write movingly about their stitching work.

Here is Yusef’s story read by a friend of mine.

Hello to you all and I hope this finds you all well and safe. Being in prison can be very difficult at times, there are so many things to deal with on a daily basis. We cannot change our pasts or the world we live in, but we can change for the better. Meeting the Fine Cell team and being part of it for me is very rewarding.

As with most prisons we are in lockdown, with this comes a lot of boredom. With the boredom and being confined to a small cell for so many hours in some cases can cause mental health issues. I have in the past suffered with mental health issues. Keeping myself occupied really helps me through the long days and nights.

Fine Cell Work keeps me occupied and for so many reasons is an uplifting experience. I take great pride in my work, this alone when seeing the finished product gives me great satisfaction.

And here is Tony’s story which for me gets to the heart of why these skills are joyful.

It’s not just about the sewing and getting paid which some might suggest is the motivation – nor is it about filling sometimes long and arduous hours of free time, though that is true for some. No, what I find most gratifying about Fine Cell Work is that my efforts are not judged in the light of my crimes, nor the fact that I am in prison, but rather on their own merits – the artistry, the attention to detail and the aesthetic pleasure they give to people. That truth and the knowledge of it is more valuable to me and more illustrative of a truly rehabilitative approach than many I have come across in the prison system. Thank you to Fine Cell Work and all those members of the public who continue to support our endeavours. You show us what our work, and thereby we, are truly worth.

So here are men, who when the gender barriers are overcome, enjoy textile skills, and derive self-worth from them, and earning money in prison is no small feat, so less risk of being laughed at.

There are lots of other men too who down the centuries have knitted or sewn: wounded and convalescent men in hospitals, lighthouse keepers locked up for long dark nights offshore, knitting ganseys, men and boys knitting socks and hats for soldiers in both world wars. Like Eric they accept at times that it something useful they can do.

But what about men who freely choose to knit and sew as a hobby – how difficult is it for them?

I was always my own person. I grew up in an environment in the South of the United States, Georgia and Alabama. And that is what everyone refers to as football country. And my, one of my uncles was a college football star. And so there was a lot of pressure for me to be a football player. I have the build, as you can see and I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to, I wanted to play music. I wanted to create, I was more interested in making things and creating things then running around, chasing a football.

Joe Sullins is a big, white, American man from the Southern States, who has a great beard. He looks as though you might find him driving a pick-up truck after a day’s hunting, but no: he spins, knits, embroiders, weaves and crochets and loves it. But he admits he has been ridiculed for it:

Oh, Oh my gosh. Relentlessly. I was, yeah. I mean, it was, it’s tough, but the thing is that throughout my, my life it’s always been about, I don’t know. I, I, the best way I can explain it is I have a Ravelry account. And most of the people I know on Ravelry, all of them have these very creative names and they’re all, you know, it’s, it’s clever puns or what have you. And yet my name is it’s Joe Sullins, it’s me. And it’s, and people will say, well, why didn’t you come up with something? And the truth of the matter is that at the end of the day, who else am I going to be? Who I already am? And for me, you know, I, I, I don’t know my, and, and I, I should probably credit my mother because she was also quite headstrong and made, you know, she fostered that in me

Joe was lucky enough to have the support of both his mother and his father. He says his mother was his most vehement ally and his father has always been wonderful and open to change and difference. Nonetheless, the pressure to conform to his gender type was intense:

Well, well, I mean, really, you know, the, the funny thing is that it was just outside of our family, our immediate family where the pressure was greatest. I mean, I had uncles that again were football stars, hunters and they were all, Oh, you have to be a manager, but you know, this is how things work and you don’t do this and that. And yeah, again, if I didn’t have the fierce and stolid support of my father and my mother, it, I don’t know. I don’t know

It has taken Joe great courage to develop his skills and to be open about practicing them for pleasure. But he has endured and his work is beautiful, lace knits, fine needlepoint, weaving and spinning.

He thinks the root of these problems lie in the association these crafts have with the home:

You know, a lot of these crafts, like knitting needlework sewing, a lot of those originate from home decoration. And so I think a lot of that has been unfortunately, well, not fortunately, unfortunately, but, you know, it’s been relegated to women as caretakers of the home.

The French have a descriptive and disparaging word for this, they describe those skills that are practiced as hobbies in the home as ‘chiffon’ – flimsy, amateurish and associated with women.

I hope that as gender definitions become more fluid, these terms will disappear and everyone, however they define themselves will feel enabled to take part in these skills.

Joe thinks that in the past schools have had a lot to answer for in reinforcing rigid gender divisions.

I’m a, I’m a child of the seventies so I, I grew up eh, yeah. Oh yeah. Everyone in high school, junior high, high school, they were all most of the boys took shop or some sort of trade related skill stuff. And the girls all did home-ec home economics, which would include sewing cooking, you know, pretty much everything.

But he believes things are changing for the better:

Years ago we had a local yarn shop and I used to teach several classes. Usually they were knitting nine one, one kind of things you know, emergencies like I’m stuck, and I don’t know where, how to figure this out. And, but because of my close work with that shop I saw tons of young professional men coming in to pick up knitting. There were several I re I remember meeting a couple of guys that were Traveling insurance executives, and they would wind up doing seminars in various places. And this, this one fellow says, well, I like to have something small, like socks to take around, or a scarf so that when I’m in the hotel, I can just, you know, sit there, watch TV and, and decompress you know and, or I’d see, I remember meeting a few doc medical students that were also picking up knitting or crochet.

Well, the nice one of the, one of the nice things about our current day and time in, in history is that all the crafts are, are really not as gender-biased, I think, as they used to, as they, maybe once were. I feel like knitting has somehow really transcended a lot of the previous roles that were, you know, I mean, it was normally your grandmother and your mother that knitted socks and sweaters, not necessarily your uncle or father. But then you have, you know, major and popular football players, like Rosie Greer publishing, needlepoint books.

Rosie Greer is a male African American former football player, who published a book called Needlepoint for Men in 1973.

Joe Sullins though remains a complete enthusiast for all fibre crafts

Oh, I love the ones, the one that I do at the, at the moment that I do it, but, and, and, and that’s, that’s really honest because when I, whenever I pick up something that I haven’t done for a while, I’m like, wow, I love this. I am so excited. And then I start, you know, thinking about other projects to make and then, but, you know, so it really is whichever one I’m working on. I get really excited about it.

I used to be just a knitter. It was, that was all I did for years and years. And I’ve, I’ve knit probably anything and everything, four or five times over that you can make with knitting. I’ve done it. And I still love it. Oh, my God. Making sweaters is so gratifying.

He is a firm believer that fibre crafts and soft making are good for people’s health and he thinks they could help address the epidemic of self-harm and suicide particularly amongst young men in western societies.

And I feel like maybe that’s another aspect that, that, that encourages people to, to delve into textiles is that it, it can mirror and, and become a part of our lives and represent those times that are, you know, okay. Maybe I had a tough time, but look at what I’ve created since then, or which would have been able to do, you know, in spite of

So there is a small but determined movement in western societies of male knitters, quilters, spinners and sewers – there have always been more male weavers as the technology, humble as it is, seems to deter them less, or interest them more. We think of this as new and cutting edge and transcending gender boundaries, but I can almost hear the astonishment of men from other cultures who are and always have been intimately involved in making and enjoying textiles:

I think in the bigger picture, men have always played a big role in the creation and production of textiles in African culture. You know, most of the weaving in African culture was traditionally done by men. Now that’s changing. I have certainly seen women Kente cloth weavers in Ghana, but traditionally many, many important textile roles were performed by men. But when I think about the African continent in particular you know, I see men as a very vital part of the cloth and textile traditions and clothing.

That’s Precious Lovell, Associate Professor of Fashion Design and Textiles at Moore College of Art and Design in Philadelphia. She has a wide knowledge of the textile practices of African and African diaspora communities. She is also an inspired and very well-regarded artist working with cloth.

She describes herself as a Stitching Griot. A Griot is a story teller in the West African tradition who has the responsibility of carrying on the narrative thread of a particular culture, city or family. She says ‘when I pick up a piece of fabric, a needle, and thread, I am reminded of how stories and histories are revealed in cloth and clothing. Excluded, under-told and forgotten stories, combined with a passion for making and materials, merge and unfold as new storylines”

I look at Ashoke in Nigeria and that was traditionally woven by men. You look at Kuba cloth from the Democratic Republic of Congo, which was formerly Zaire. It’s a collaborative effort between men and women, the men weave the rafia base cloth and the women embroider the patterns and these patterns that the women embroider are held in their memory. Let’s see, Oh, Bogolanfini Malian mud cloth is also a collaborative effort. Again, the men weave the base cloth and the women paint the patterns onto the cloth. The Kano Indigo dye pits, which I believe established in 1498 in Nigeria they’re staffed by men who do the Indigo dying there. In Ghana, again, the Asafo flags, the beautiful Asafo flags 6:09 are appliqued primarily by men. And again, all of these traditions you know, are starting to pivot and women are doing many of these things now, but I’m talking about traditional production. The prestigious Hausa robes of Northern Nigeria were traditionally embroidered by men.

So weaving, dyeing, embroidery, applique, all of these things. So men have been involved in textile production on the African continent you know, for as long as it has existed

And by the sound of it, carefully guarded their knowledge and their own skills. Precious says that if you suggested to these male textile makers that their practice should somehow be just the domain of women – they would disagree.

It was never anything that was looked down upon. It was actually something that was honoured and respected. So as long as you’re doing something that’s honourable and that your culture respects why would you, why would you know, you think that you were doing something less than, or something that only belonged in the world of women.

She traces the loss of this respect and the disappearance of textile practices amongst men in Western societies to the industrial revolution, which mechanised production and relegated hand-made to the home:

Maybe because after the industrial revolution, it became sort of the, the realm of women and women have decided to protect the things that they had such a big part in developing, maybe you know, I think that there is a sort of global movement at the moment of going back to traditional textiles and trying to preserve them as so much technology is coming into the world with regard to cloth and clothing production.

And I think that I think women know how much, you know, time, effort and knowledge and skill goes into all of these practices. And they know that these things should not be lost to technology. And I am not anti-technology, but I’m saying that they both need to co-exist. And I think that’s a part of the, you know, slow fashion movements and slow textile movements and really trying to preserve these traditions. And I think maybe, and I’m certainly not an expert on this, but that man had just, you know, sort of abandoned these, these ideas on a, on, on a grand scale. Men certainly still do these things, but I just think that women maybe perhaps at this moment have a greater appreciation for them.

But Interestingly she had good male role models in her own family:

But when I look at my own family and I’m, African-American, my father always had a sewing machine. He you know, for hemming his pants and for doing minor repairs, my grandparents owned and operated a dry cleaning business. So my grandmother was always doing alterations for people. So it was normal within our family. My dad’s older brother, my uncle Jim, he did needlepoint. He stitched a reproduction of what was it called? The Unicorn Rests in The Garden from the unicorn tapestry series that were developed between 1495 and 1505, I believe. So it was not unusual in my own family for men of African descent to sew and do needlepoint.

Jo

And did they attract ridicule for that?

Precious

No, nobody was going to mess with them in my family. They absolutely did not. No. I don’t know that they’re maybe their friends or something, but no, as far as I knew again, because it was something that, excuse me, all the women in my family did. My, all of my great aunts and my grandmother, as I said, my mother, everyone had the ability to sew beautifully. I was really blessed to come from a family that had these traditions. And there was just nothing unusual about the fact that my dad and his brothers could sew and stitch it was normal. Yeah. I’m not saying that it’s the case in every family. I’m just saying that for my family, it was not unusual.

She too tracks the rigid gender divide in the practice of these skills to the school programmes of the post war period, where boys did Shop and girls did Home Economics:

But that certainly that absolutely played a big part in that divide. And to be perfectly honest, it’s, it’s sad because so many of those programs have been eliminated from high school curriculum now. And, you know, we’re finding at the university level that some very basic skills, students are now coming into university without them, basic stitching skills and, and, and, and engineering skills that can be developed from both sewing and woodworking, you know, so they’re lacking in some of those skills. And I really think that they should be re-introduced to high school curriculum, maybe even middle school. Ooh. But but they should not be gender specific. Anyone that wants to take any of them should be allowed.

And she believes that our societies are infinitely poorer for not practicing and teaching these skills.

Oh my gosh. I just think that all of those things involve, you know, critical thinking and planning and, and, and developing, developing, you know, a course of action. And I think that is applicable in every aspect of our lives. So I think it’s really important to do those things for very basic reasons.

But there’s more than that and both Precious and Joe understand this very well, as I think do most makers. Using our hands to create things or repair them gives us a sense of satisfaction and a release from our troubles. It also gives us a connection to humanity that transcends gender, politics, culture, and geography. It attaches us to the people who have gone before us and those who are yet to come, who have and will join us in darning and sewing, quilting, knitting, weaving or spinning and derive pleasure from practicing their skills, using their hands and eyes to protect their families and communities and to tell their own stories.

Oh, absolutely. From my own personal practice,e I have said to people many, many times stitching has saved my life. Now. I don’t mean anything super dramatic, but what I mean is I can be really stressed about something and I can pick up a needle and thread and start to stitch and two things can happen. And sometimes both of them happen. I can completely forget about whatever my trouble was or as I’m stitching, I work it out. You know, I calm down. It’s methodical. It is the most amazing experience when I pick up a needle and thread. I’ve I have often said that stitching is not second nature to me. It’s first nature to me. I think about it every day. If I could, if I could, I would stitch every day. It is the thing that, that connects me to myself. And the thing that connects me to the world at large, it is just, you know, it literally, it’s like, you know, stitching my life together, constantly, stitching things together to make them make sense. It really is. For me.

Joe Sullins gets the final word:

At least from my perspective, there’s something really wonderful and satisfying about taking something in your hands and using oftentimes really, really simple tools to make something that you can use and, and appreciate, and, and also still handle it. I don’t know. I mean, you know, baking, I like to cook and I love baking, but, and that’s a lot of that is the process of doing things with your hands and, and making something. But after it’s eaten, it’s gone, it’s now a memory, you know, a faded memory. When you make something, some kind of textile or something with your hands, even, you know, art or sewing, stitchery, what have you, anything you do with your hands, it’s always going to be so much more satisfying when you have a, a product, a finished product to appreciate maybe pass on maybe give away.

This episode of Haptic and Hue was written, narrated and edited by me, Jo Andrews. Many thanks to Precious Lovell, Joe Sullins and Eric Bacon for sharing their thoughts and their making practice with us.

You can see pictures of them and some of their work at www.Hapticandhue.com forward slash listen.

You can find show notes there, where I provide a complete transcript of this podcast and a list of resources and background reading that you might enjoy.

You can sign up there to get these podcasts directly into your inbox and have a chance to win the textile-related gifts that I give away with each episode. You will also find blogs and other information about textiles and Haptic and Hue there.

Next time will be the last episode in this series. To finish off, we will be reaching right back into the past to find out how the world communicated the idea of changing fashions before printed drawings, photographs, and moving pictures made it easy. We will be following the fate of a doll called Pandora through the firelight of European history from the medieval era right up to today.

Join me next time and Thanks for listening.