Catch her out of the corner of your eye as she skitters across the stage of history. She has seen revolutions, war, disaster, pandemics, peace and joy, and survived it all. She is probably 3,500 years old, maybe more. She is called Pandora.

This episode looks at the unseen role miniature mannequins, or Pandora figures, have played in diplomacy, war, royalty, communications, and marketing, down the centuries from the time of the Egyptian pharaohs, through the Second World War, until today. Not bad to have been in fashion for several thousand years.

This podcast would not have been made without the knowledgeable and heartfelt contributions of Rebecca Devaney, textile educator and embroiderer, Steve Grafe, Curator of Art, Maryhill Museum of Art, and Sean Byrne, Maquitiste and proprietor of Madame Fou Fou.

Rebecca can be found at Textile Tours of Paris or on Instagram at textile_tours_of_paris.

Steve Grafe is at Maryhill Museum of Art in Washington State. Keep an eye on the site, they will be launching an online exhibition about the Theatre de la Mode in January 2021. The Museum is also on Instagram

Sean Byrne can be found on Instagram

Here is the Moschino Spring/Summer 2021 Collection referred to by Steve Grafe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7dpNzuRda0Y

And here is the wonderfully fey Dior collection for Autumn/Winter 2020, referred to by both Steve Grafe and Sean Byrne. It has a lot of shots of the work on the tiny models on their ateliers. The skill is astonishing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yxBFwqRbI8c

If you would like to sign up for your own link to the podcasts as they are released, for extra information and a chance to access the free textile gifts that I’ll be offering for each podcast in this series then please fill out the very brief form below.

If you are interested in a long read or two, or want to know why and how cloth speaks to us then you can find articles at www.hapticandhue.com/read

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name. You can see more of my work and that of other makers there or on the website.

And if you’ve got a great idea for Series Two (coming next year) then drop me a line via the website.

Have fun and enjoy your own making practice or just listening to the chatter of cloth!

Further Reading and Resources:

Here is the link to Maryhill Museum of Art, which cares for the Theatre de la Mode https://www.maryhillmuseum.org/inside/exhibitions/permanent-exhibitions/theatre-de-la-mode

Christine Shaw Checinska: TED Talk, Disobedient Dress, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=63-9YIVAhpI

Lydia Maria Taylor’s article, called Pandora in the Box, was a mine of information.

https://www.academia.edu/1751676/Pandora_in_the_Box_Travelling_the_World_in_the_Name_of_Fashion

Dolls, by Antonia Fraser can be brought cheaply on Abe Books or other sites.

https://www.abebooks.co.uk/book-search/title/dolls/author/antonia-fraser/

Early Georgian Pandora figure

Pandora made for the Queen of Sweden

Jointed wooden Pandora

Faience – Lucien Lelong, Theatre de la Mode, Maryhill Museum

Lucien Lelong – Short Dance Dress, Maryhill Museum

Crepe Dress by Mendel – Theatre de la Mode, Maryhill Museum

Cocktail Dress – Agnes Drecoll, Maryhill Museum

Cocktail Dress – Nina Ricci, Maryhill Museum

Poudre de Iris – Jacques Fath

Palais Royale set, Maryhill Museum

La Place Vendome, Set for Le Theatre de la Mode

Croquis de Paris, Maryhill Museum

Madame Fou Fou, Maquette

Madame Fou Fou

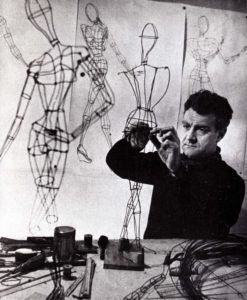

Jean St Martin, making the Mannequins, 1945

Script

Majesty and Mannequins

The English poet John Donne, wrote a wonderful poem in the early 1600s called A Nocturnal upon St Lucy’s Day. It begins like this:

‘Tis the year’s midnight, and it is the days.

Lucy’s, who scarce seven hours herself unmasks.

The sun is spent, and now his flasks send forth light squibs, no constant rays.

The world’s whole sap is sunk.

And here we are, nearly at the longest night in this difficult year. St Lucy’s Day, or the feast of Sant Lucia is December 13th. In Donne’s time, because he was using a different calendar, the 13th was also the darkest day of the year. For us in the northern hemisphere we will have to wait a little longer for the solstice and the wonderful moment when we begin the long slow climb towards the light again.

I am well aware that my friends in the southern hemisphere are moving into glorious mid-summer, but for the rest of us, it is time to pull the curtains, stoke the fire, draw up a chair and enjoy a story that comes out of the beginnings of history and continues right up until today.

Welcome to the last episode in this series of podcasts from Haptic and Hue, which looks at textiles of all kinds down the centuries and thinks about the role they play in our lives and the hidden hands that make them. I’m Jo Andrews, I’m a handweaver, and collector of stories about cloth. Haptic means the feel of something and Hue describes the pure spectrum colours.

This tale is about how ideas of style and changing fashions were communicated before printed drawings, photographs, moving pictures and social media made it easy.

It follows the fate of a mannequin, or doll-like figure called Pandora, through the firelight of history. A doll, you say, surely not: but I think her story goes to the heart of why clothes are important and what they say about us as people, what we value, how we express power, status, gender and the social and moral restrictions placed on us by our own age.

Christine Checinska, a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, says in a wonderful TED talk she gave:

“Things make us, as much as we make them.”

“Fashion is part of the process by which the unequal distribution of power within society is constructed, maintained and experienced. But fashion can also be used to challenge and contest one’s position in society”

It’s hard to know exactly when this story begins. I suspect that way back when we wore skins before cloth was invented, there would have been a cool way of wearing the stuff, if it was over that shoulder then you were behind the times, but if it was done like this with the belt tied like so, then that was hip.

I’m not sure anyone is an expert on Neanderthal fashion, but I bet they had ways of dressing that told others if you were male or female, married or single, successful or not.

Spinning forwards, we do know that a small human figure made of wood was found in Tutankhamen’s tomb – dating from 1300 BC. It was close to his clothing chest and academics believe that this may be one of the first fashion mannequins.

They were invented as an elegant solution to the problem of how to transmit changing ideas about style and fashion in a world where pictures could not be easily transmitted.

I have often wondered why some of the more extreme styles of dress, like the vast panniers of the Baroque era that made it impossible for women to pass through a door or sit down, or the bustles of Victorian times – become fashionable: why did women start to wear them, or for that matter why did men move from wearing a slashed doublet and a codpiece to a grey suit and tie?

Part of the answer lies with these miniature figures. They were Europe’s way of spreading new ideas about clothes and creating demand for them at a time when travel was difficult and fraught with danger. They were both an effective means of communication and a form of smart marketing.

Rebecca Devaney

But then these Pandora dolls as we see them, if we’re looking at it through a fashion point of view, yes, they’re very, very important. Before the advent of magazines or fashion illustrations or fashion plates, these little Pandora dolls were used to spread fashion throughout Europe and then across the Atlantic to America, and then throughout the colonies.

So fashion merchants would make up dresses in miniature and they would go through very long discussions with their clients about which ribbon to use, which lace to use, which buttons to use, which fabrics to use on which styles overall to use as well. And because at that time, everything was made by hand or made with kind of, you know, the best of materials, they were made in miniature first because it was cost, It was cost-effective. It just wasn’t an option for people to make up a full-size version. And then for the client to say, no, thanks. I want that in blue, or I want that in pink. When, you know, when lace is made by hand you need to make sure that your customer is going to agree with that you’re going, that you’re proposing to use.

Rebecca Devaney is an embroiderer and textile educator based in Paris. She has been tracking Pandora mannequins and, in particular, their role in helping to establish Paris as the first centre for fashion and style. We think of this as a relatively recent development something that happened in the last 250 years, but the small Pandora figures tell us that it goes back much further than that.

Rebecca Devaney

These Pandora dolls it said that they were used from the middle ages and that they had a really important place between the Royal courts in Europe. So the queen of France would send a gift of these dolls to say the queen of England. And generally once the dresses were made in miniature by the dressmaker, they, when the client was happy, the queen or princess or whoever it was, it would be made in life-size. And then once the dresses had been worn in court in the French court, then those miniature dolls could be sent around the Royal courts of Europe in Germany and Italy and Spain and England and so forth.

The first written records of these wooden or wax figures date back to the 1300s. French court records show us that in 1321 the French Queen sent fashion mannequins as a gift to the Queen of England, and then again in 1396, the Court Tailor of France, Roger de Varennes made a miniature wardrobe to be sent by Queen Isabel of Bavaria to the Queen of England, as an early form of diplomacy.

We know that Mary Queen of Scots, who was brought up in Paris, had a set of Pandora figures and that she and her ladies in Waiting – the four Mary’s – dressed them in different costumes while they were in Scotland.

When we think of Mary Queen of Scots, and her particular grace that comes down the centuries, she is wearing black velvet and white lace. This is how she chose to be painted and how she wished to be seen, and her mannequins played a central role in how she and her ladies in waiting worked that out.

Think too of Elizabeth the first of England, red headed, in magnificently embroidered costumes in russet colours, studded with jewels, huge sleeves, lace ruff, and the story of the Pandora mannequins makes you realise that the royal courts of Europe used ideas of fashion to project their majesty, to elevate themselves from the people and to help their subjects understand that they were Queens to be served and obeyed, which at that time was a difficult thing for a woman to pull off. The clothing was a central part of their display of power.

Rebecca Devaney

It wasn’t just fashion, like at that time fashion and everything that went with it, fabric lace, ribbon, embroidery all the undergarments and so on, so forth, they were hugely important to the French economy. And I think it was Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the minister of finance in the 17th century declared that fashion is to France what the gold mines of Peru are to Spain.

Perhaps because of their association with royalty, the little figures always seemed exclusive and desirable. Their heyday came in the 18th and early 19th century, as transport improved, aristocratic courts across Europe multiplied and tailors round the world began to order their own transportable mannequins to showcase their wares.

Men and Women became fascinated by fashion for the first time, and especially in England, far larger numbers could afford it as a prosperous mercantile class emerged. This was the start of the fashion retail market.

Every detail was perfectly made for the miniature mannequins, from the underwear to his or her hair and hats.

Rebecca Devaney

Your hair style was extremely important and hair like your coiff or your coiffure was made of a huge amount of, you know, there’s a lot of artifice went into it. It wasn’t all your own hair. And hairstyles could be built up and open up with extra wigs and things like that. And they, it was important for women that their hairstyles matched or were in, I suppose they were following the latest fashions from France as well. So the dolls would also have these beautiful hairstyles and they’d have beautiful shoes that have beautiful jewellery, everything was communicated and they would also at times have beautiful hats because in certain occasions you would be showing off your hairstyle, but in other occasions, you’d be showing off your hats. So both of these things had had importance depending on where you were going, depending on the occasion

The more I look at Pandora mannequins and their travels, the more they seem to skitter across the stage of history. You glimpse them out of the corner of your eye but never quite see them full on, perhaps because it’s hard for us now to understand the fascination people had for them and the joy with which the news that a new set of mannequins had arrived in town would be greeted.

It wasn’t just tea that the ships in Boston Harbour were carrying in 1773 which sparked the American Revolution, there was also a set of Pandora dolls on board too, or as they were known in America, ‘French babies’.

In the wars between Britain and France at the start of the 18th century the mannequins were exempt from trade embargoes, given a so-called “inviolable passport’ and a sort of cavalry escort, and, despite war, continued their journeys from Paris to London and beyond without hindrance.

Gradually as the 19th century progressed, the mannequins were replaced by cheaply published magazines with coloured fashion plates, and as the twentieth century arrived, the plates were replaced by photographs and, by rights, that should have been the end of the little mannequins.

But it wasn’t. Pandora figures refused to die and they have gone on to have several more lives. And part of their power lies in the way they play on our imagination, our hopes and aspirations, our fantasies that clothes will make us somehow different, more attractive, more successful and wealthier.

In 1945, Paris, like the rest of Europe, needed some of that. It was destitute after 5 and a half years of war. To raise morale, to show the French themselves that they were still a capable nation with skills and style, and to raise funds for humanitarian relief, a new set of Pandora mannequins was created to send round the world. Over 50 French couturiers took part, and they must have raided their pre-war fabric stashes, no doubt secreted away during the Occupation, to fit out more than 200 small wire figures, which were arranged in a series of tableaux called Le Theatre de la Mode – the Theatre of Fashion.

Steve Grafe:

It was important for the French public to see after four years of occupation that couture still existed and that it had not lost its creativity or its fine workmanship. And in fact, as we’ll probably talk about later, this is really important because they weren’t necessarily created as a commercial advertisement by the French fashion industry, but they were more about making a statement about the ongoing creativity and workmanship that was present there in Paris.

Another thing was that it illustrated that the, the sets and the mannequins illustrated the links between the worlds of art and fashion, which had been something that had been going on in Paris since early in the 20th century. And that’s why some preeminent stage designers and artists had been hired to create the sets. One of the, one of the really important things about the mannequins they were being made in 1945 and 1946, is that they establish the link between pre-war and wartime fashions and Christian Dior’s New Look that changed everything in 1947. And the last one, and I think this is extremely important is what the Theatre de la Mode as it exists now is, is a collection of 172 outfits from 52 fashion houses all from a single season. And that’s, you know, doesn’t really exist in any other collection.

That’s Steve Grafe, Curator of Art at Maryhill Museum of Art in Washington State, high above the Columbia River about 100 miles east of Portland, Oregon. He is an expert in this postwar collection of Pandora Mannequins.

Steve Grafe:

They were designed by a woman named Ellian Bonnie bell, who was a pretty well-known illustrator in Paris. And at the time of the Tatra Della mode was conceived in 1945, she was working for Nina Ricci’s a fashion house. And she had recently designed its logo and according to the 1946 catalog. So that would have been the New York catalogue.

She was thinking of an, of an outline sketch. And then she went from that to transforming that idea into three-dimensional space. And that would suggest then that you could use wire to create a body with a plaster head that was light and, and idealized let’s say, and that they could be created to have different postures that then would work well with the fashions that were on them. And then the next step in the process, she had been working and worked in the future with a Parisian sculptor named John St. Martin who had himself been involved in creating a different kind of wire mannequin. And he was the person in his studio, in his apartment, who then made all of the mannequins out of wire. He shaped the wire, twisted the wire, and then soldered it and made all of the mannequins. I sure would have loved to have seen a photo of his interior space where there are dozens and dozens of them completed. The heads were made by a Spanish sculptor, a Catalan sculptor who was known for sort of graceful slender figure forms. And he’s the person who made all of the heads. So each head is unique as is each mannequin

Each mannequin is just 27 inches high, around 70 centimetres. But despite their make do and mend genesis – they were full of life and ingenuity, each figures has its own character and way of standing, every stitch is perfect, every fold on the tiny wire shapes precisely executed, and they were dressed in millions of dollars worth of jewellery.

Steve Grafe

So the important thing about the mannequins, and it’s something I have to keep reminding myself because I get carried away with the story, is that they were made to benefit France in general and, and their travel throughout Europe and North America was to, to help fund French relief. So there wasn’t a commercial aspect to the Le Theatre de La Mode. In the beginning, there was an aesthetic aspect, the fashion designer, Lucien Lelong who was president of the Organization of Fashion Houses wrote an introduction to n the 1945 catalogue that accompanied the London exhibition. And what he said in the introduction is that the Theatre de la Mode was not intended to represent luxury or lavish use of materials, but it was instead of proof of ingenuity and good taste. And I think absolutely the traveling show affirmed that. So I would say Theatre de La Mode did exactly what it was intended to do.

The mannequins went to London, Leeds, Stockholm Copenhagen, and Barcelona, and then they were sent to New York and lastly to be exhibited in San Francisco, and then they were almost lost from view. No-one in Europe was quite sure what happened to them:

Steve Grafe

The jewelry was returned to France because it had maybe a $2 million total value. And then the mannequins and the fashions were stored in the San Francisco City of Paris department store appropriately in 1950. So a couple of years, less, several years later, the head of the department store a man named Paul Verdier at the encouragement of a San Francisco philanthropist called, Alma de Brecksville Spreckels, who is also considered one of Maryhill Museum of Arts four patrons. She encouraged Mr. Verdier to get together with the director of Maryhill Museum of Art. They had a luncheon in San Francisco and talked about the collection coming to Maryhill. The museum’s director Clifford Dolphy returned home. And this was in 1950 and didn’t hear anything for two years. And then in 1952 in the spring in March, more than 80 cases with their original, April’s still attached, arrived at the museum, but the cases only contain the mannequins and the fashions and the sets somewhere along the way had been lost.

The sets were eventually re-created in Paris and the Pandora mannequins were re-united with their proper settings. There are 172 of the original mannequins in Washington State, a long way from home, but carefully looked after. Steve Graf says different types of visitors come to see them.

Steve Grafe

We have neophytes, people who don’t know anything about them who kind of are wowed by, wow, this is strange. I thought the location of this museum was strange already. And now I’m really convinced. Things are strange here. That seems to be the majority of the people. We also have people who make the pilgrimage specifically to see the sets and the fashions. And some people will do that every two years as they rotate on the view. And then we have a third set where it, people come to see them because they think they’re clever dolls. And just me personally I bristle a little bit when the word doll is overused because it kind of diminishes the importance and the aesthetic value of the mannequins.

These beautiful figures are now 75 years old, they have been round the world several times, not just before they got to Maryhill, but on loan to other museums, since then, and in 1988 back to Paris to be spruced up. But Steve believes they have worn well.

Steve Grafe

Well, that’s a great question because I imagine any 75 year old clothes in your closet, some fabrics will wear well and others won’t. And some that have been exposed to light on the corner of his shoulder will be faded a little bit happily for most of their lives. Tempted automotive has been stored in a museum environment with controlled humidity and controlled light, and all of these other things. We have low light levels in the exhibitions. People complain about it all the time, but they are 75 years old. I think they look pretty well.

The aspect of Theatre de la Mode that’s problematic for us right now, though, is the mannequins themselves. Because if you imagine a wire, that’s a little lighter weight than a clothes hanger wire, that’s been soldered in dozens of places on a single mannequin. That’s where the great fragility comes is, is in, in the stability of the mannequins. And that’s why they’re handled so carefully. And so infrequently, if we can, if we can make that happen.

There are requests for them to travel all the time, but since 2015 the old ladies have rested in their home at Maryhill, too fragile to be shifted across oceans anymore. Mary Hill Museum of Art will open an online exhibition of Le Theatre de La Mode in January, it will show new photographs and lots of detail about the mannequins and beautiful clothes they wear.

Until this year these figures would have been seen as a quirk of fate and history, but in 2020 – a new disaster – the COVID pandemic – has seen the little mannequins rise again.

Steve Grafe

People who are paying attention to fashion in 2020, appreciate that the 2020 runway shows were a bust because of the pandemic. And as a result of that Dior’s fall, winter creations were showcased in a 15-minute long video that shows them. And that was, in fact, itself inspired by Theatre de La Mode, and what the video shows is a large crate with a drop-down front that has a bunch of miniature fashions in it, and a couple of men carrying them around. So the different women can see them and then order them in full size. It’s easy to find. It’s absolutely worth 15 minutes of anybody’s time. And then there’s another one that’s really quite lovely. Moschino’s spring, summer 2021 creations are, were presented in an online marionette show, and it’s just fantastic because you’ve got people sitting behind the runway that are miniature people marionettes, and then you have marionettes in the spring-summer 2021 fashions going down the runway.

I have posted links to both the magical Dior Show and the Moschino marionette show on the Haptic and Hue page for this podcast. They are an enormously fun and imaginative response to a new time of crisis, one, that very effectively references our pasts as well. Creating these new Pandora dolls has demanded a fantastically high level of technical skill to work in miniature:

Sean Byrne

But the Dior collection was just, it was spellbinding. It was just so beautiful. It was just really stoning. And I don’t like those people that make, that make those clothes on their mannequins are just, they’re just wizards, they’re obsolete wizards to have the hands, to be able to, to finish things perfect. Like that was, I was told it was insane. (22:02):

Sean Byrne works and lives in Paris. He has a very particular calling in the production of modern fashion collections. He is a Maquitiste, which involves, yes, working with miniature figures – the descendants if you like of Pandora dolls.

Sean Byrne

One thing that’s used very heavily in a lot of the haute couture houses in Paris a lot of the ready to wear houses in Paris are these little guys called maquettes and they’re they’re little small quarter size mannequins. And you basically, you use your hands to create concepts with fabric. And so it was a very free flowing way of design. You take a piece of cloth and it might just be some Calico, or if you’re working with like a stiffer fabric, you might be taking a piece of kind of silk taffeta or some, or something like that.

And you’re pinning it onto the mannequin. And, and you’re allowing your hands to kind of just work with the form or the shape of this little mannequin and basically, a kind of it does your bidding for you in a way. It, it, it, it develops your concepts along with you. It’s almost like a, for want of a better word. I remember doing it for the first time. And my professor said to me, you look like you’ve done this for a long time. So she said, this has, she said, this is where you need to go in fashion because this is what you’re good at. And I was really pleased to hear that because, when I start to do is, I didn’t know what I was doing, right, I didn’t know if I was doing wrong. But with, with, with working with the maquette, there’s no real right or wrong way to do it.

For someone who is a designer of clothes this skill frees up your imagination and creativity, its an approach that is only taught in France particularly at the wonderfully named Ecole De La Chambre Syndicale de La Couture Parisienne.

Sean Byrne

And I think it’s something where you either have the, you have the free skill to do it, or you don’t. And I think, cause I’ve told about it quite a lot, and I think it’s basically just the way your mind thinks. And if you’re not afraid of us, if you’re not afraid of going outside the box and not, you’re not afraid of like, you know, you’re not thinking in millimeters and centimeters, you’re thinking in a conceptual kind of way of doing things. If you have a mindset like that, it will work really well with you. And there’s a strange alchemy to it because you come up with designs that you never, you physically could not make. It’s just a pleasure that I’ve allowed, that I’ve had the opportunity to, to, to let it come into my life because it really gives me an awful lot of joy because even if I’m not working on anything to do with, like, if, if I’m not working on a project or anything, you can just sit with that mannequin and for an hour and just play around. And all of a sudden you’ll come up with kind of fantastic concepts that you’d never come up with just pen and paper.

Maquettes are used because they don’t waste expensive fabric and because they set designers free to experiment in a way that flat pattern cutting doesn’t.

Sean Byrne

So a maquette is a quarter size mannequin, and so it was probably about, I think maybe two feet tall and has little arms on us. It has its own little head and it’s on a little dress stand. And you basically just yeah, it’s just like, it’s like a little miniature mannequin.

So what I’m looking at is more of a concept kind of thing. So it’s very related to that kind of that French heritage of designing on a smaller scale. It’s really, really important in French fashion on it’s been around for, I know a very long time and for me as a fashion designer, it’s just, it’s, I’d be, I’d be lost without it because it’s such a help.

And I think with the little guy, the little one that I have, you can just develop concepts very quickly, and you might have a scrap of fabric that would be like nearly ready for the bin. Cause it’s so small, but you can do something, you could do something with it on a maquette.

Each fashion house will have a team of maquitistes, working in house producing possibly hundreds of ideas each week.

Sean Byrne

If you wanted to make volume and again, if you want it to make volume in a sleeve, if you wanted, you know, large billowing skirts, anything like that, the maquetistes would come in and they would be very quickly able to put together those concepts. If a designer came in and said today, I want to look at necklines. And I want to look at, you know, different kinds of like, you know, small collars with volume underneath them. They would give the Maquetistes the brief and the Macquitistes could go away then for the whole day or for a week or whatever. And they’d experiment with different volumes. Very, very quickly. They could come up with a concept. And what’s great about a Macquitiste, is you can put your little bolt of fabric on the arm of your mannequin. And within maybe a minute, you’ll know, if a,sleeve that you had in your head is working or not.. You take a photo of that. You take your fabric off, you keep the same piece of fabric and you put it a different way. You put it upside down, you turn it around, you bring it up towards the neck, you bring your arm line towards the neck, you drop it down underneath. And it’s a very quick concept because every two or three minutes, you’re seeing different shapes. So it’s evolving constantly, whereas with the larger mannequins, it’s, it’s a more, it’s a cumbersome process. Whereas the maquitistes you get to play around with shapes and, you know, you can see your design come to life immediately at, so they’re just, they’re so useful.

Sean’s own Maquette which he keeps in his apartment, is called Madame Fou Fou, – he believes the miniature mannequins like her, are integral to creativity in design.

So even today, the Fashion figure, the little Pandora mannequin has her or his place in creating and designing what we wear. Sean says the Maquette opens new doors for him:

Sean Byrne

It brings for me, it sounds a bit cheesy, but it brings my heart into the design completely, because it’s like a process between….. fashion is a very solitary work I find, being a designer can be quite solitary. And working on garments can be a solitary task, but you nearly have someone with you when you have that, when you have that little mannequin and you know, that it’s nearly like you’re working with it, it’s helping you along the way. It’s bringing itself into the situation. It’s bringing itself into the concept and to have that too, because that’s what it is for me. It’s a tool that allows me to push my vision more. It allows, allows me to think outside the box and it just, it pushes my fashion to an, to a level that I could never achieve with flat pattern cutting and or with like fashion illustration or anything. This just has been, has enabled me to take things to another level of design that I actually didn’t think I had in me.

In 1990 the celebrated Irish Poet Eavan Boland wrote a poem called The Shadow Doll. It was about the Irish tradition of the wedding dress maker in Victorian times giving a bride a miniature doll dressed in a replica wedding dress as a keepsake. In this poem the figure, keep under glass, is used as a motif of the memories of the wedding day and the family life that followed, but also expresses how women often experienced marriage as constricting:

Here it is read by Rebecca Devaney.

Rebecca Devaney

They stitched blooms from ivory tulle,

to hem the oyster gleam of the veil.

They made hoops for the crinoline.

Now in summary, and neatly sewn

A porcelain bride in an airless glamour

The shadow doll survives its occasion

Under glass, under wraps it stays

Even now after all, discrete about

Visits, fevers, quickenings and lusts.

And just how, when she looked at

the shell tone spray of seed pearls,

the bisque features she could see herself

inside it all, holding less than real

Stephanotis and rose petals , never feeling

satin rise and fall with the vows.

I kept repeating on the night before

astray among the cards and wedding gifts,

the coffee pots and the clocks and

the battered tan case full of cotton

lace and tissue paper pressing down then

pressing down again. And then locks

This episode of Haptic and Hue was written, narrated and edited by me, Jo Andrews. Many thanks to Rebecca Devaney, Textile educator, Steve Grafe, Curator of Art at Maryhill Museum of Art in Washington State, and the Paris based Fashion Designer, Sean Byrne –for sharing their thoughts and their expertise with us.

You can see pictures of Pandora dolls at www.Hapticandhue.com forward slash listen, as well as the Dior and Moshcino videos.

And You can find show notes there, I provide a complete transcript of this podcast and a list of resources and background reading that you might enjoy.

You can sign up there to get the Haptic and Hue newsletter. You will also find blogs and other information about textiles and Haptic and Hue there.

If you feel able to give this podcast a rating, or even a review, on your podcast provider that would be wonderful, it increases the chances of others enjoying it as well as making it more likely that I will make future series.

I am already planning a second series for next year and if you have ideas for an episode please do contact me at jo.andrews@hapticandhue.com

I am going to leave you with a quote from that master of textile design and production Alistair Moreton who ran Edinburgh Weavers from the early 1930’s to the 1960’s and who came through some hard times of his own.

“The arts may seem frail and superficial activities when we are beset by the more grim realities of life. But in the long run I am sure this is not so. Let us not forget that at all times the world has been coming to an end. Life has always been more dangerous, more fleeting and yet the arts have persisted, moulding our history. In the perspective of history it is only the persisting ideas, the frail values of the arts that we have available to us to stand up against the brutalities of politics and commerce and the indifference of science.

Thank you for your company it has meant a great deal to me these difficult months, enjoy your making or just listening to the chatter of cloth and I hope to re-connect with you next year.