The Long and Winding Road of Lace

Episode #31

This episode of Haptic and Hue is about one of the most intricate and complex human skills ever developed – lace-making. But it is not just about the deeply storied history of lace, it’s also about its modern revival as a new and beautiful art form and how contemporary craftswoman and men are using lace techniques to address complex issues like gender, sexuality, and climate change.

The people you hear in this episode are:

Elena Kanagy-Loux, who can be found on Instagram as @erenanaomi. She is also on TikTok as https://www.tiktok.com/@erenanaomi She is the Founder of the Brooklyn Lace Guild. And she has her own Youtube Channel where she has all her recordings on lace. Elena also mentions in the podcast Lace in Context: By the Poor, For the Rich – by historians Dr. David Hopkins and Dr. Nicolette Makovicky which is a blog on lace with a number of wide-ranging articles. Elena works at the Met Museum in New York, which has nearly 5,000 digitized pictures of lace in its collection.

Jane Atkinson is on Instagram as @jane.atkinson_contemporarylace. Her website is https://www.contemporarylace.com/ where you can find her blog, pictures, and other pieces of interest. she is also the author of Contemporary Lace for You which you can buy from her website.

Pierre Fouché is on Instagram as @thelacemakersnotebook And you can find his website at www.pierrefouche.net

Both Jane and Pierre teach lace making and you can find their classes, with all previous episodes recorded and available at www.theadventurouslacemakers.com; https://www.patreon.com/join/theadventurouslacemakers.

If you are in the US on the East Coast there will be an exhibition of lace: Threads of Power: Lace from the Textilmuseum St. Gallen at the Bard Graduate Center in NYC, September 16, 2022 – January 1, 2023. Brooklyn Lace Guild will be artists in residence in a studio space on the 4th floor for the duration of the exhibition. They will also hold a special event for lacemakers on September 24.

Lace Organisations:

Germany: https://www.deutscher-kloeppelverband.de/.

Spain, Girona: www.puntairesdegirona.cat

Netherlands: https://www.lokk.nl/

UK: https://www.laceguild.org/

USA: https://internationalorganizationoflace.org/

Australia: https://australianlaceguild.com.au/

International: https://www.oidfa.com/

Tutorials and masterclasses for beginners to advanced:

With tutors Pierre Fouché, Jane Atkinson, Denise Watts and Dagmar Beckel-Machyckovà, www.theadventurouslacemakers.com; https://www.patreon.com/join/theadventurouslacemakers

At Doily Free Zone you can find a database of pre-recorded online courses in contemporary lace techniques taught by artists around the world.

Museums with Lace:

The Lace Museum in Sunnyvale, California – offers all manner of live virtual classes in traditional lace techniques including beginning bobbin lace, needle lace, Irish crochet, etc.

Northern New Mexico Museum of Lace – has a growing online collection of lace and ephemera.

Identifying Handmade and Machine Made Lace – pdf created by DATS and the V&A in London.

The Smithsonian, Washington: https://www.si.edu/

The Lace Museum, Sunnyvale CA: https://thelacemuseum.org/

Lacis, Berkeley CA: https://www.lacis.com/

The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl

St. Gallen Museum, Switzerland https://www.textilmuseum.ch/en/ .

Czech Republic (pioneers of Contemporary Lace), Prague Museum of Decorative Arts: https://www.upm.cz/

Vamberk (centre of their old lace industry): https://www.moh.cz/muzeum-krajky and

There are also many great smaller lace museums in Plauen, Germany; Calais, France; Chantilly, France; Arenys de Mar, Costa Brava, Spain; Burano, Italy.

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney: https://www.maas.museum/powerhouse-museum/

Lace Museums in the UK

Museums showing lace collections:

Allhallows Museum, High St., Honiton EX14 1PG

Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle, County Durham DL12 8NP

Fashion Museum, Assembly Rooms, Bennett Street, Bath BA1 2QH

The Lace Guild, The Hollies, 53 Audnam, Stourbridge DY8 4AE

The Higgins Art Gallery and Museum, Castle Lane, Bedford MK40 3XD

Wardown House Museum, Old Bedford Road, Luton LU2 7HA

Cowper and Newton Museum, Market Place, Olney MK46 4AJ

Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Queen Street, Exeter EX4 3R

Books for Learning:

The Torchon Lace Workbook by Bridget M. Cook

Beginner’s Guide to Bobbin Lace by Gilian Dye

Contemporary Lace for You, by Jane Atkinson

Books for Lace Identification:

Lace Identification: A Practical Guide by Gilian Dye and Jean Leader (just came out in November 2021!)

Identification of Lace, Dictionary of Lace, and Lace Machines and Machine Laces by Pat Earnshaw

Books of Lace History:

Lace: A History by Santina Levey

History of Lace by Mrs. Bury Palliser

Lace in Fashion by Pat Earnshaw

Romance of the Lace Pillow by Thomas Wright

The History of the Honiton Lace Industry, by H J Yallop

Individual Lace-Makers of Possible Interest

Tina Koder, Slovenia: https://www.idrijalace.org/en/designer-lace-products

Lauran Sundin, USA: http://lauransundin.com/

Pierre Fouche, South Africa: http://www.pierrefouche.net/

Cordula Profrock, Germany: lacebutwhy.de

Veronika Irvine, Canada: https://tesselace.com/

Erna Futselaar, Netherlands: https://ernafutselaar.nl/

Jane Atkinson, UK: https://www.contemporarylace.com/

Marian Nuñez, Spain: https://marianlilu.myportfolio.com/work

Marjolaine Salvador-Morel, France: https://marjolainesalvadormorel.fr/

Bistra Pisancheva, Bulgaria: https://www.bistrapisancheva.com/

Agnes Herczeg, Hungary: https://www.agnesherczeg.com/

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Elena Kanagy Loux – Photo by Rose Callahan

Elizabethan Cartwheel Ruff

Franz Hals’ Laughing Cavalier with Falling Lace Collar

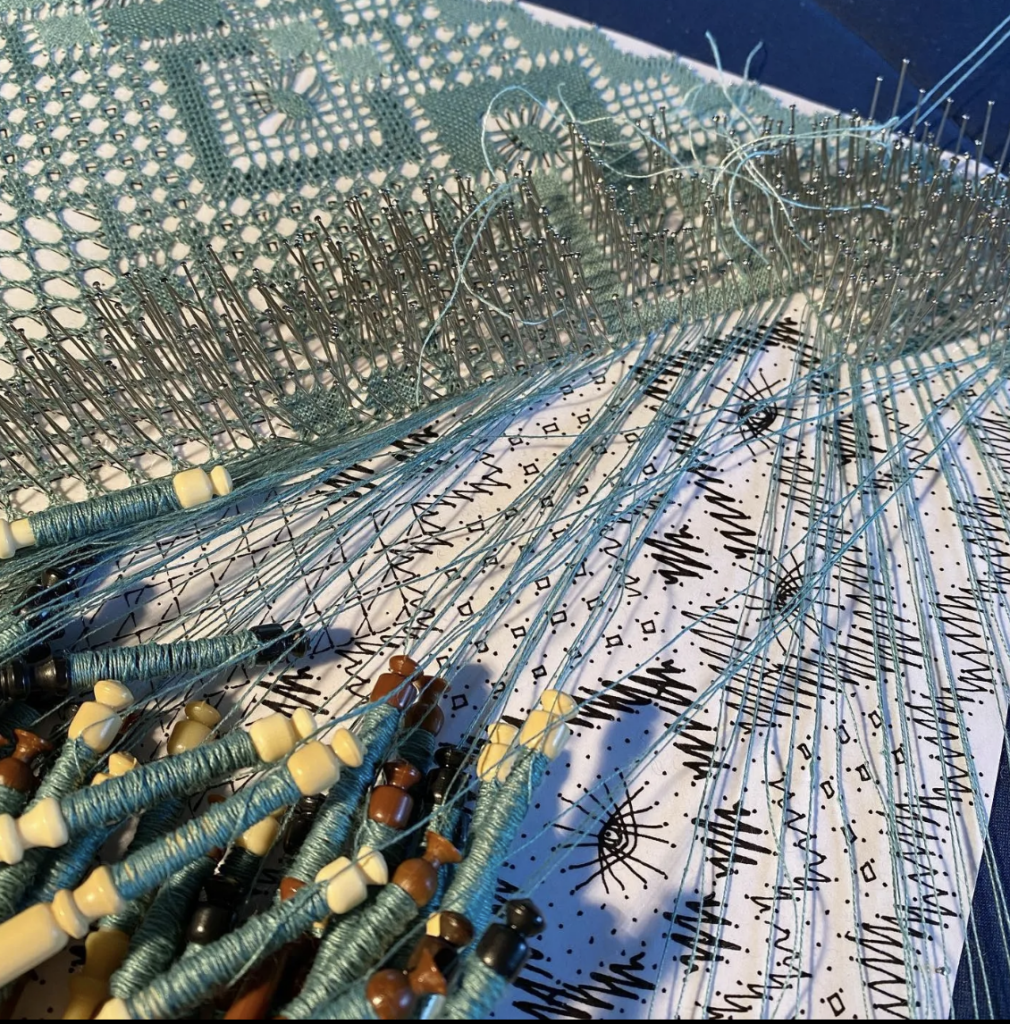

Jane Atkinson Making Lace

Close up of Jane Working

Jane Atkinson’s work On the Trawl (edited)

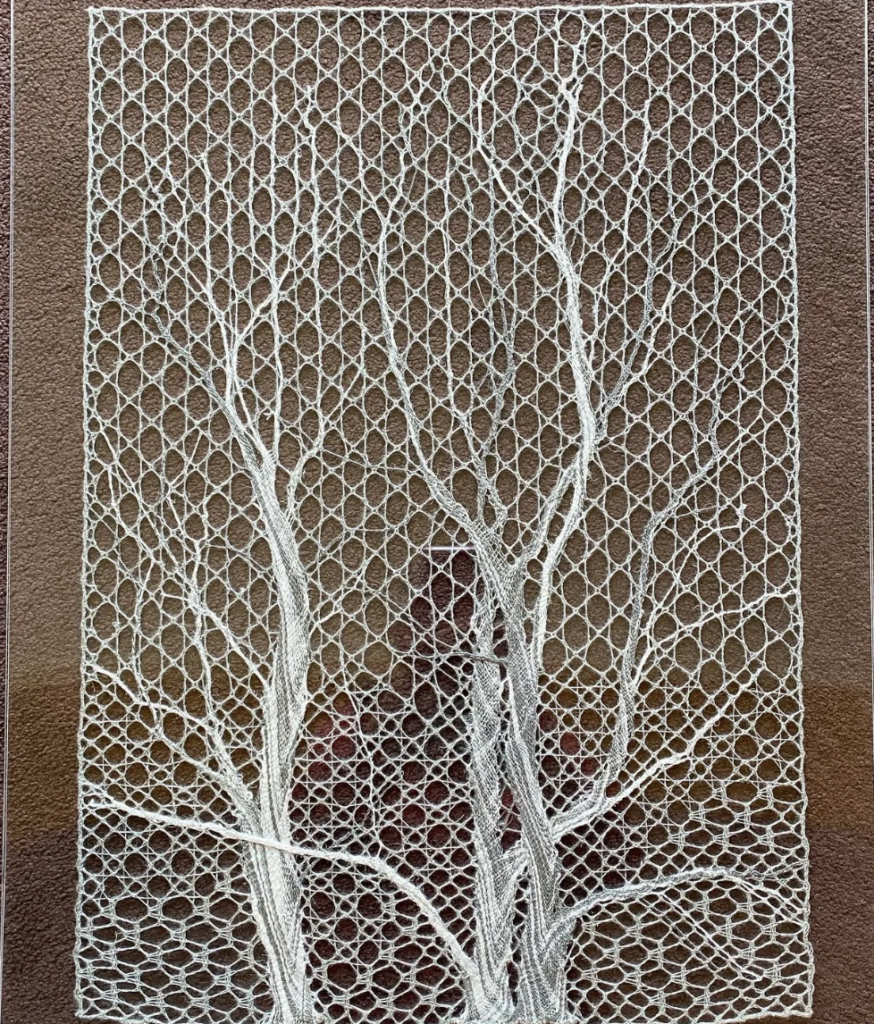

Arbor Mortis – Jane Atkinson

Lace Notation – Jane Atkinson

Mike Andrews in Christchurch Harbour

Christchurch Harbour – A Smuggler’s Paradise

Pierre Fouché

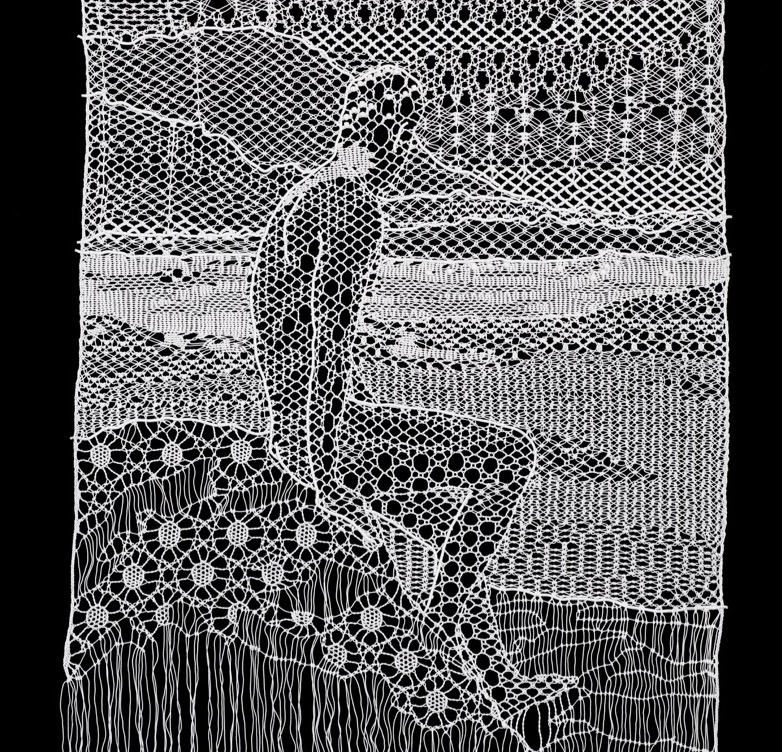

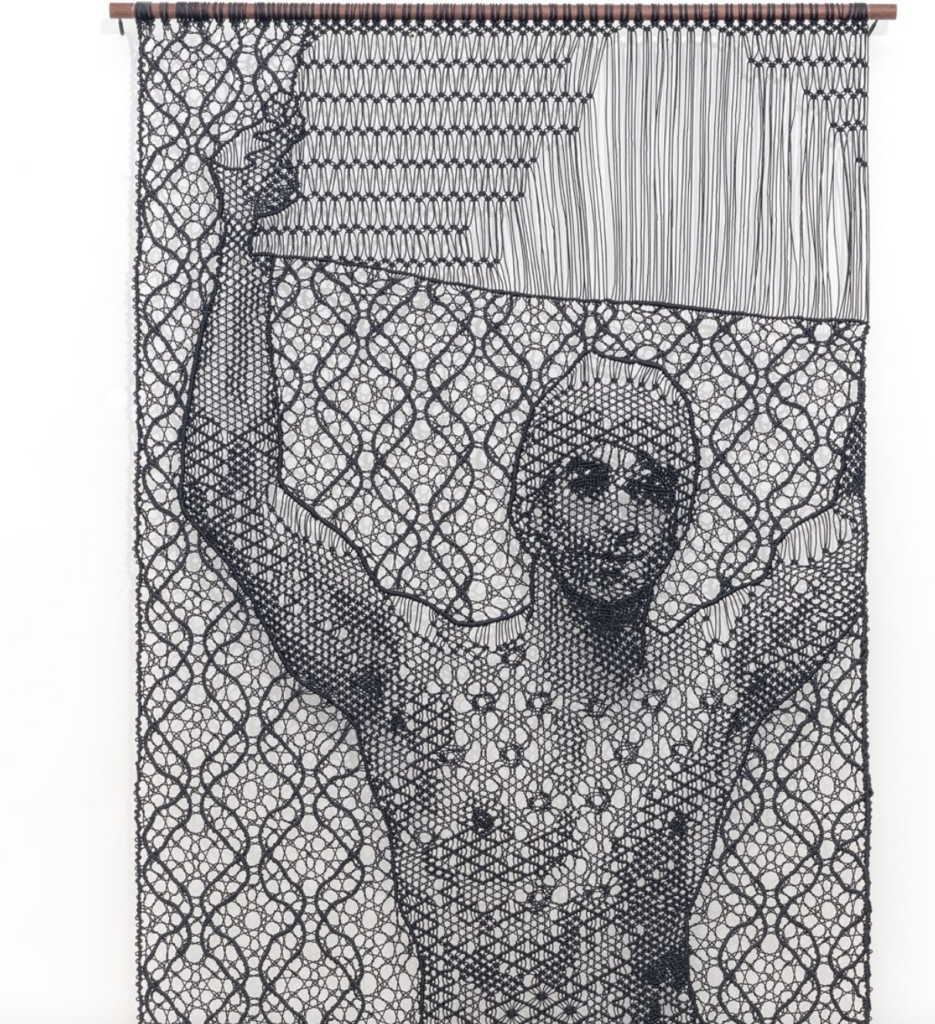

The Burden of Excess – Pierre Fouché

Aggregate of Countless Moments Pierre Fouché

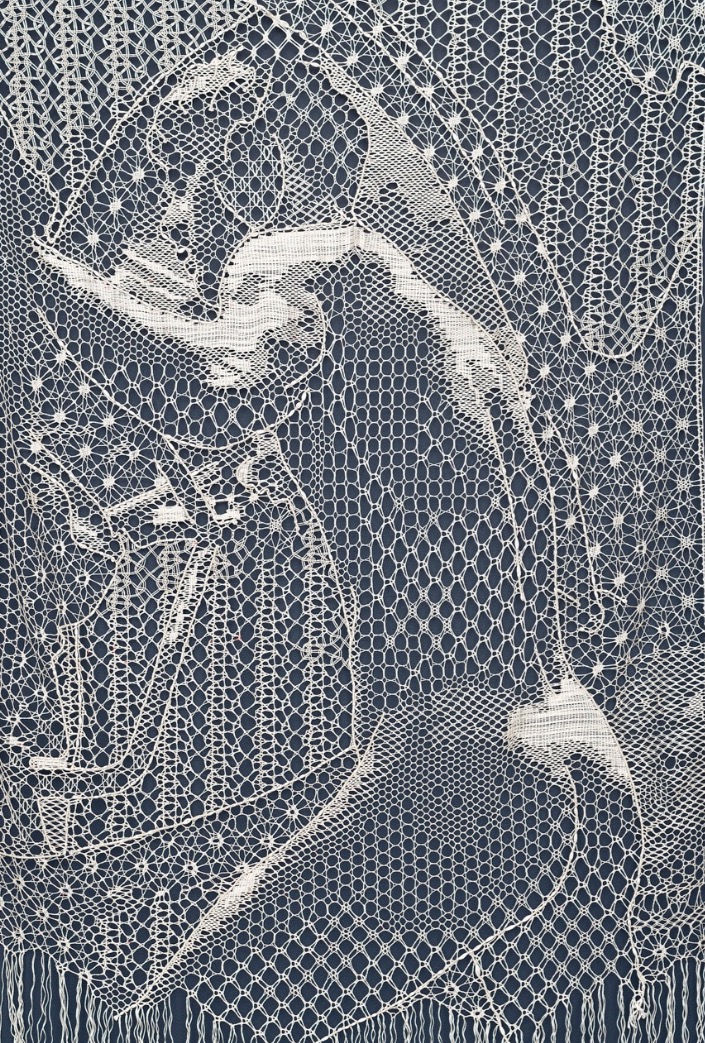

The Judgment of Paris (after Wtewael) III. Pierre Fouché

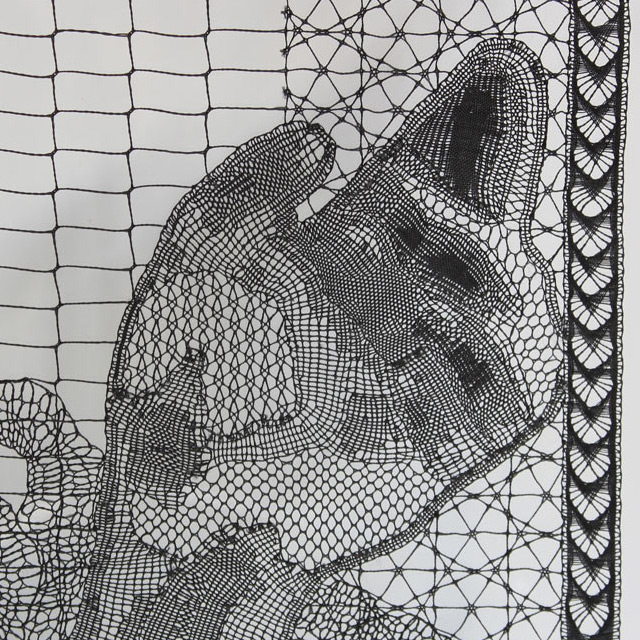

Lace Detail in a Hand – Pierre Fouché

Script for the Long and Winding Road of Lace:

There’s fact and then there’s fiction or myth, and when you are talking about an intricate human skill like lace-making – that has been passed down the generations by word of mouth – sometimes the legends tell you as much if not more, than the facts:

Elena: So it’s a really beautiful origin myth of lace making. And essentially it goes that long ago, a young sailor went fishing at sea and was suddenly surrounded by a group of enchanting mermaids. They tried to seduce him with their songs, but he would not be swayed as his heart belonged to his beautiful fiancée back on the island, impressed by his devotion, the queen of the mermaids, gifted him, a veil of ethereal seaweed also described sometimes a sea foam or coral depending on the version, which he took home to his bride and the girl was a needle worker and struck by the elaborate structure of the veil. She imitated it in small stitches with her needle and thread and produced a delicate textile, which quickly became the taste of all Europe.

That’s a story from Venice and telling it is Elena Kanagy Loux, who is a lace researcher and maker, and if I am granted a second life I’d quite like her job, she’s the Collections Specialist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Antonio Ratti Textile Research Centre in New York. And for the record here are the facts about lace:

Elena: Bobbin and needle lace kind of evolved in tandem out of two different techniques: needle lace out of cut work embroidery, which was worked on plain weave linen fabric. And then the patterns were cut out and buttonhole stitches were worked into them to create elaborate patterns. Eventually the base fabric was discarded and they worked directly onto the pattern base itself on parchment paper initially. So, this was called in Italy at first “punto in aria or ‘stitches in air’ because you’re doing embroidery into the air instead of on the base. And that’s how you create needle lace. Whereas bobbin lace developed out of braiding techniques, similar to passmenterie, it’s the sort of elaborate metal braids you see on military uniforms and things like that, or in upholstery still made today. And as it became increasingly elaborate bobbins and lace bobbins were attached to the individual threads to keep them organized. And essentially this is like someone describe it to me as cursive braiding. And I think that’s quite apt. It is in fact, a bit of circuitry.

Welcome to Haptic and Hue – and Season 4 of Tales of Textiles, called Threads of Survival. My name is Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver interested in what cloth in all its forms tells us about ourselves as human beings. Textiles have an incredible power to talk to us if we can hear them. They comfort and console us, create memories, and define who we are. They can tell others what we think and more than anything they tell us what sort of society we live in.

This episode is about lace, those elusive stiches in air as the Italians call them. But not just the extraordinary past of lace in which it has been a generator of poverty and harsh conditions for some – usually the female makers – and great riches for others, where it has been stolen and smuggled, desired and displayed by both genders as a sign of taste, fashion and status, it is also the story of how lace in the 21st century has risen from the ashes like a glorious phoenix and from being one of the most despised and discarded of crafts is now producing some of the most interesting and alluring modern art. Lace today is something great aunt Mildred would struggle to recognise, it is being deployed in all its complexity and beauty by skilled makers, to say something important about difficult issues like climate change, gender and sexuality. It has come a very long way from its apparent beginnings in early renaissance Europe:

Jane: People do reckon that it probably goes back to the 1400s but you see edgings in portraits, Tudor portraits. So, they start off really quite dainty and, and fine. And then they blossom into the Elizabethan ruff. There are some wonderful pattern books, which were published in the mid 1500s probably for amateurs rather than professionals. But, the ruff, you know, blossomed in all its gorgeousness and, and that’s where lace really took off.

Jane Atkinson is a fourth-generation lace maker and one of the leading lights in the modern lace movement.

Jane: The ruff developed into the falling collar, the Cavalier falling collar, and the, the cartwheel type ruff kept going on the Continent, I think longer than it did in England. but the Stuarts started wearing these falling collars. And whereas the early laces were spidery and geometric, the falling collars were much softer and they became more floral, you could do all sorts of things with, with, with those designs.

Jane is talking about the time of the Civil War in England, the war between the Puritans and the Cavaliers in the 1600s, and it was the Cavaliers, who supported the King, who loved lace.

Jane: They had lace everywhere and, you know you’d have it on your boot tops or rosettes on your shoes, collars and cuffs you know, fans. Everywhere you could have a trimming, you could use lace. I mean, the gentleman in the Restoration period, you would have these boots with lace over the, over the tops, you know, <laugh>, they just loved it. And, and it’s so lovely to think of men enjoying, wearing lace.

By this stage the beginning of the 1700s most of Europe seems to have acquired a serious lace habit – one that took quite some funds to supply:

Jane: The thing is it’s very pretty, isn’t it? And it’s very detailed. And once you get into lace, , you develop an eye for the differences between the different laces and, you know, fashion progressed from one type of lace to another. So, you had to keep up with it and you had to have the right kind of lace and worn in the right way. When the periwig came in that covered the shoulders there was no point in having a falling collar, because that would all have disappeared. So, gentleman had these wide cravats with a big area of lace over the upper chest and the most fashionable lace for that kind of thing was heavy Venetian needle point, gros-point. And that was completely different lace again from the early Stewart laces. So, there was no point in having your Van Dyck falling band made into a cravat because it would’ve been completely the wrong thing.

And people were prepared to pay huge sums of money for lace, and the higher their status the bigger the bills, Jane has been looking at the lace bills of the British King and Queen William and Mary at around the time of Mary’s death:

Jane: The best place really for extravagant lace bills is the Royal wardrobe account and William and Mary were a very tight unit. It’s one of those marriages that really developed from inauspicious beginnings and her last lace bill was the equivalent of about a quarter of a million in today’s terms. And William went into mourning afterwards and his next lace bill after that was nearly the modern equivalent of 300 thousand pounds. So, though a cravat could cost 50 quid when you multiply that by at least 10 times, they just wanted it and so they got it.

Just like other fine and complex fabrics, lace had by this stage become a marker of status, the more lace you had the greater your standing. In the early days of lace many European courts passed laws forbidding people below a certain rank to wear it.

Jane: Sumptuary laws have been going since medieval times and there was a point at which I think nobody below the rank of knight was allowed to wear sumptuous trimmings. So, I mean, not just here but in France. And I think you can replicate this in most, most countries, but everybody, everybody wore what they could afford. I mean, it’s really sad to think that you might make lace, but not be allowed to wear it. But it was very, very popular right through the 1700s until fashions changed in the latter part of the century and became simpler and muslin became the thing.

But in the 1700s lace had become so commonplace that the police were forced to issue advice to women travelling in horse-drawn carriages in London:

Jane: there was an account that I came across about how thieves would slit open the back of a carriage and steal the lady’s headdress wig and all. And because they have these, these marvellous lace headdress with lappets and feathers and, and all the rest of it. And so the police advised that ladies would, should sit with their back to the horses. <Laugh>

And because it was so desirable and expensive, taxing lace, and other luxury goods, was often the answer to the prayers of a cash-strapped government, but taxing goods has an inevitable consequence:

Mike: Well, for, for most of the 18th century, Britain was at war with somebody or other. So, we were either fighting the French, the Spanish, the Dutch, the Americans. And, of course, these wars were worldwide and we were trying to defend an empire and the cost was horrendous. So, a duty was put on goods, especially luxury goods as a way of raising money. And people were poor and people needed to make money and they could make a lot of money out of smuggling. Fortunes were made out of smuggling along this part of the coast.

That’s Mike Andrews, no relation, and we are sitting in his small boat deep in the reeds on a sunny morning in Christchurch Harbour in Dorset. Mike is a local historian and a specialist in the extensive history of smuggling along this coast. He explains why this harbour was a smugglers’ paradise:

Mike: Because it’s got an awful lot of features, which was so beneficial for smuggling. Firstly, it’s a sheltered harbour. Secondly, it’s got a rather difficult entrance and you’ve got to know your way in, there are a lot of sandbars on the outside of it. It’s got two rivers which flow into it, which means you’ve got river routes inland. It is close to some really good hiding places for goods. So that’s the New Forest and what was Bourne Heath, which is where Bournemouth is today. That was all open heathland. It has gently shelving beaches on the outside, no steep cliffs, no nasty rocks. And probably the most important reason is it has two tides. So, if a ship’s captain has missed the first tide, there’s a second tide that comes in and he can get in on that. One of the few places in the world, I think that has two tides.

Mike says the latter part of the 1700s was the golden age for smuggling and this particular part of the Dorset coast was the epicentre of this activity with thousands and thousands of barrels of brandy and other illicit luxury goods like French lace coming ashore here:

Mike: We have a very good story on lace. That was actually smuggled by individuals. They had a very clever modus operandi, and a particular lady by the name of Lovey Warren who actually came from Burleigh, and her brothers were into smuggling, but she had a wonderful method. She would wait for, obviously, this has been prearranged, but she’d wait for the ship to come into Christchurch Harbour, up to the quay at Christchurch. She’d go on board on the pretext of seeing the captain, go into the captain’s cabin, where the lace was waiting. She’d take her clothes off, wrap herself in lace and silks and any other valuables and then put her clothes back on and then walk off the ship and wave bye-bye to the captain. She was very nearly caught at a pub called the Eight Bells, which was a well-known smuggling pub in Christchurch. It’s now a gift shop, but it’s still there. And she went in one day after one of these operations and sat down with a, a cooling drink. And one of the customs officers came in, a new man who hadn’t been in the area long and obviously took a shine to Lovey, and sat down beside her. And at the point he ran his hand up her leg she knew she had to get out <laugh> she could be discovered. So she quickly slapped him and left. And I don’t think she visited the pub again, after she got very close to being caught.

And make no mistake this may have been a game of cat and mouse but it was also big business, fortunes were being made but, if people got caught there were consequences to take.

Mike: it could vary depending on one’s involvement. There were all sorts of laws that were brought in from various times, as obviously smuggling went on for some time. So legislation was coming and going all the time. You could be fined. There was an incidence of a smuggler in Lulworth who had a quarter share in something like a lobster boat, a family of eight. And he was caught smuggling, obviously poor as a church mouse, brought in front of the magistrates and the magistrates fined him 20 pounds. The smuggler walked up to the bench, put his hand in his back pocket, took out 20 pounds, slapped it on the desk and walked out. The money was incredible. One smuggler had admitted to a turnover, he sort of turned King’s evidence and admitted to a turnover of 40,000 pounds a year. The money made was incredible. Other punishments, of course, when you got into any sort of conflict with the Revenue and there were injuries, then obviously the punishments were more severe and it could be death or transportation.

But what of the lace-makers themselves, the people who created these deeply desirable items with the skill of their fingers, how did they fare, and did any of these riches come to them? Here’s Jane:

Jane: You could make a decent living. If you were a good lace maker, you could live an independent life, which was pretty unusual for a country woman. And I’d say quite a lot of lace was made in the countryside. Although I think a lot was made in towns, especially in Devon, but by and large, it was the equivalent of an agricultural worker’s wage. I think women could have been proud of keeping themselves you know with their skill. But the conditions were not good. The days were long, and if you were working in a group the rooms were crowded and it was very easy to transmit tuberculosis between them. You were under the control of the lace manufacturer who would give out the patterns and the thread. So, you weren’t able to make lace on your own account or sell it for yourself unless you could somehow get hold of the thread. Thread came in though from abroad and was heavily taxed, I think you paid about 25% on lace thread, which would be coming in from Flanders. And so money was tight and you could quite often be paid on the truck system where you had to take some of your wages in goods from a shop under the control of the manufacturer.

But no matter where you were this was a communal activity and many kinds of lace makers created songs or tells to chant as they worked. Here’s Elena Kanagy Loux.

Elena: So lace-making is very difficult to learn in isolation it’s so it’s often necessary to join the community in order to learn, to make it well. And you know, for me, I feel as a lace maker, myself, that all of the knowledge that I have directly comes from the vast community of lace-makers that today and that came before me. So, I always think about, you know, embodying them when I’m working at my pillow. So, it, it, to me, it makes sense that in this spirit of community that they would develop these stories together in, in lace

There hasn’t been enough work done to know if songs and tells from lacemaking regions in France, Spain and Italy have simply been lost on the winds of history, or if they never existed, but most of those that have been documented come from Flanders or Britain and Ireland.

Elena: So many of these tells come from the well-known book on lace history, The Romance of the Lace Pillow, by Thomas Wright. And they’ve also been published more recently by Dr. David Hopkins at Oxford, but sadly many lace tells with enticing titles like Blackberry Nan, The Squire’s Ghost and Little Goblins Hole have been lost to time, but also many have survived. So one of the most well-known English lace tells goes as follows:

Needle pin, needle pin, stitch upon stitch, work the old lady out of the ditch. If she is not out, as soon as I, a rap on the knuckle shall come by and buy a horse to carry my lady out I must not look till 20 are out.

So this is counted with the placement of pins. And after you would recite this together the lace makers would count out 20 pins while they worked. And if any lace maker looked up from her pillow before she finished, the others would cry out,

Hang her up for half an hour, cut her down, just like a flower.

To which the lace maker in question would reply, indignantly perhaps:

I won’t be hung up for half an hour. I won’t be cut down like a flower

And then they would repeat.

These aren’t pretty rhymes for comfortable lives, they are reflections of tough and often gruelling lives that many lace-makers led:

Elena: The patron saint of lace in Le Puy en Valais in France, Saint Regis, is a real story of the struggles of lacemakers in their earliest days. So Jean-Francois Regis was a Jesuit priest who lived in France from 1597 to 1640. And at the time Northern Italian lace was at the height of fashion. So particularly from Milan and Venice and the French monarchy under Louis the 14th tried very hard to sort of squash the desire for imported lace by passing sumptuary legislation against it. But this, unfortunately, caused the lace makers of Le Puy to become destitute. So St Regis saw that many of them had been forced onto the streets or had turned to sex work to survive and went to the French parliament in Toulouse to fight for the laws to be overturned and amazingly he succeeded. And today he has been canonized by the church and is still celebrated by lace makers in Le Puy for his support of the industry.

In England one of the curiosities of bobbin lace making was that lace makers marked great events with commemorative bobbins, they even marked sensational crimes that resulted in the death penalty with special so-called ‘hanging bobbins’:

Elena: There are only about seven known examples and the two sorts of best known are the hanging bobbin commemorating Sarah Daley’s hanging in 1843 in Lavenham in Bucks. And Daley was executed for poisoning her husband with arsenic in Wrestlingworth, Beds. And her conviction was sensationalized given that she was only 22 and it was rumoured that she had also killed a previous husband in the same way and intended to do it five more times. It is said. So, this was made into rare bobbins, although none are known currently. Perhaps the most well-known and heart-breaking also story is that of Joseph Castle, who was hanged in 1860 in Ravenstone, Bucks, forgive my American pronunciation. Castle was an abusive man, sadly married to a lace maker named Jane. And when she left him, he stalked her and eventually murdered her. So, Castle’s case caused a sensation by the way that it was solved. It was a bloodhound from the Luton police station that sniffed out enough evidence to convict him for murdering his wife. And on the night of his hanging, his wife’s friends held a huge celebration where each guest was given an engraved bobbin as a memento. it’s a heart-breaking, but poignant story because it’s the celebration of justice against a beloved friend and lace maker.

Jane Atkinson’s great-grandmother, her grandmother, and her aunt were all lacemakers in gentler times. They learned to make a specific lace in the 20th century that comes from just outside Salisbury called Downton lace. Jane herself has lived on the edge of Christchurch Harbour, in Dorset which is not that far away, for close to 40 years, and most days she walks around part of the harbour called Stampit Marsh:

Jane: And over that 40 years, I began to be aware that I could see it changing. And there are so many beautiful patterns that rise to the surface of water or even just the ripples on the water and the plants along the path. And I ended up making an exhibition from all of these things, drawing the inference that much is changing on the marsh. Whereas I started off making designs from thick patterns in the winter ice, this gradually got thinner and thinner until we’re hardly getting ice at all as the winter has warmed and the water’s rising higher over the path. And so really climate change has become the thing that I find really interesting to bring to people’s attention with the work that I do.

This is as far away from the kind of lace making that our grandmothers and great grandmothers would have recognised as you can get. Jane’s lace is not destined for a gentleman’s ruff but instead to make a much deeper point. Her lace marries beautifully the sense of fragility and the textures of the environment around her: the tides of the creek, advancing and receding, and the disappearing ice. Her work almost allows you to hear oystercatchers on the wing above the harbour, arriving earlier and earlier every year because of climate change, or to see the arching limbs of ghost trees damaged in the more frequent storms that have come as the weather changes. This is serious work in service of a cause and it is important. Jane is one of a number of modern lace-makers creating fresh work that deserves to be seen and appreciated far beyond the small community of lace makers – there is something about the combination of the intricacy of lace, the skills in manipulating it, and the multitude of textures and shapes that it can produce that enables lace-makers to give a new form and meaning to art. Pierre Fouché is one of the leading lace-making artists:

Pierre: Many contemporary lace makers like myself have discovered that lace is an incredibly versatile medium with which you can do anything. It is the perfect medium for expression because firstly it has a colourful history, you can represent anything with it in any style and with any mood or emotion. So, it needn’t be limited to its traditional forms. Now the traditional forms are really exquisite and they are technically ingenious and you cannot, but be awed and silenced when you look at a piece of historical lace at the fineness, the delicacy, the complexity of lace in its traditional form is exquisite. It is in my mind, probably the highest form of textile manipulation that one can get, if you imagine that it started with just the idea of interlacing loose strands of thread, and it evolved over time to become this incredibly complex system of patterns and organic weaving with which you can create irregular shapes. I think in that sense, it also represents our aspirational side that as humans, as a species we can aim higher. We can take a basic thing and explore it to its limits and that we can solve hard problems, and lace captures that. So, in a sense, I’m hoping that by using lace in my work, that I can also restore a little bit of faith in humanity, that because we are clever enough to have figured out this incredible technique, maybe we’re clever enough to solve our big problems too.

Pierre grew up as a gay man in South Africa – where he lives and works.

Pierre: Of course, as a queer artist, I will also have an activist streak in me. And so I think lace fits that role to a T. I’m still engaging with that iconography representation in my work. Just because I grew up in the eighties, oh, there was zero representation when I grew up, so I think that, that famine of role models just made it clear that one of my main goals is to provide as many images representing queerness as I can.

And using lace to create images of queerness is a leap of genius. The finished works Pierre has produced and the points he is making are all the stronger for being made in lace. The magical fragility of lace but its strong definition and durability gives these works immense power, they describe and depict beautifully and do it in a technique that is far removed from traditional masculinities.

Pierre: It was a combination of all these aspects coming together and my being in the right place at the right time giving the right message. Now that I’m a little bit more established and I think our world is also changing so rapidly. I think my activism is also incorporating other areas now, environmentalism and just a concern, for where we are culturally, ecologically. I think lace is a very useful medium for that, too, because as I mentioned, it represents the best of us and also the long arc of history of where we’ve been, where we’ve come from, what we’ve become in the sense that lace is an evolution of a textile technique. It started with, a basic thing, and then it becomes something special. So, I think that is where I’m at, at the moment in my view, of what lace means.

Pierre’s road to lace was through his grandmother who taught him needlepoint, he then progressed to crochet and onto lacemaking. His work is successful and he is able to command art prices. He is well aware of his privilege compared to many of the female makers who cannot do the same.

Pierre: I was already an established artist when I arrived at lace. So, so I think that is maybe my unfair advantage as to other lace-makers trying to break into the art world, which is hard enough, for even trained artists to do. I had already had a solo exhibition showing two of my tapestry works and also my sculptural assemblages.

Jo: So you were able to make a living doing that

Pierre: Tentatively at first. And, and later on, later on as a, as a professional full-time artist. Yes, that was my head star, into being able to make lace and sell it for a living, because many contemporary lace makers don’t have that luxury because they don’t have an in the art world.

Pierre also believes that the modern revival of handmade lace – freed now from its shackles of being a desirable fashion item – is helping to blur the boundaries between art and craft

Pierre: I think our views of art and craft is changing and for the better, I think those strict divides are not that relevant anymore. I think contemporary artists are relishing blurring boundaries. And I think contemporary crafters are also realizing that their work is important <laugh> as they rightly should. It’s those, those lace makers of old, even though they were just going through the motions, turning out lace as fast as they could that involved, incredible skill learned over years and years, of doing and making. And it is that learning that one gets from making it, that gives it value. And I think contemporary lace makers realize that and can start to exploit that in substantiating what they do as art.

Elena Kanagy Loux in Brooklyn, New York also sees lace as a way to question and re-draw boundaries.

Elena: I tend to get polar opposite responses. Either people are utterly dismissive and say, lace, you mean grandma doilies? And I say, yes, in fact, grandma doilies, I celebrate them. But the other reaction that I get increasingly and much more frequently than the negative one or dismissive one is that people are just overwhelmed. They’ve never considered that lace ever had to be made by hand and it boggles their mind to see it. So, you know, younger people today I think are really drawn to these sorts of things that they don’t necessarily have the same baggage as their mothers or grandmothers did, for example. And, you know, there are so many younger people questioning gender norms and embracing femininity and domesticity in these different ways. So, thanks to the internet and social media lace makers are now able to connect all over the world and there’s been such a positive outpouring over these techniques that I really see lace-making on the precipice of an exciting new era.

In talking to the lace-makers what struck me more than anything is the sheer joy they take in lace making. I think from time to time most of us get frustrated with our work – I know I do – but for the lace-makers, there seems to be this extraordinary delight in what they do, here’s Jane Atkinson:

Jane: The first time I, touched bobbins, I felt I saw stars. It was a physical reaction bit like being kicked in the head. And I get a great sense of peace and contentment when I make lace. Even if I haven’t been able to do it during the day, because I’ve been busy with other things, I look forward to sitting down with it in the evening, and I feel that it refills the bucket that I’ve emptied during the day. And I go to bed serene and, and calm, we all know that it releases endorphins that make you feel good. I just think lace-making ought to be on the national health. You know, it’s just so good for you. <Laugh> and it keeps your brain supple you know, lace makers, if they’re lucky can go on into old age, my favourite lace maker and German lace maker, Leni Matthaei died at 107. So we’re all keeping our fingers crossed that we can follow in her footsteps.

Thank you for listening to this episode on lace. I need to express my profound gratitude to Jane Atkinson for prodding me until I understood what a great story this is, it really has everything, from poisoners to smugglers, from great historical figures addicted to lace to good modern art with something important to say and some incredible skills behind it. Thanks to Mike Andrews for a great trip on a perfect day across Christchurch Harbour to understand how the smuggling worked, to Elena Kanagy Loux for keeping a fierce flame burning for lace-makers in the US, and to Pierre Fouché for his artistry, activism, and depth of thought on craft and art – now that was conversation we could have spent hours on.

As ever there are pictures, book recommendations, links to lace courses, a full script and more on the Haptic and Hue website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen. Haptic and Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production that is supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee. If you would like to contribute you will find the button on our website at www.hapticandhue.com. We will be taking a rest next month, August, but join us again on the first Thursday in September for a new episode of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’ll leave you this time with a poem found and read by Elena Kanagy Loux, it was written in 1651 by the Flemish poet Jacob Van Eyck. Here’s Elena reading it in English translated by Gwenda Lin Grewal and Travis Qualls:

Of many arts of young women one surpasses all; the threads woven by the strange power of the hand, the hanging threads which Arachne would in vain attempt to imitate, and which Pallas would confess she had never known.

For the maiden, seated at her work, plies her fingers rapidly, and turns round the smooth pillow a thousand threads into a circuit.

Often with her hand she fastens, and again unfastens the countless pins, to express the various patterns from her imagination; and in this amusement makes as much profit as the man earns from the sweat of his brow; and no maiden ever complains at even of the length of the day.

The issue is a fine web; permeable to the winds with many an aperture, which feeds the pride of the whole globe; which encircles with its fine border cloaks and bands, and looks brilliant round the throats and hands of kings; and, what is more surprising, it is equal in weight to a bird’s feather, which outweighs our purses in its great cost.