Britain has been a quiet place these past weeks: no planes, no pubs, few trains, and no traffic, except for the sad howl of ambulances. But if you listened carefully you might just have been able to catch the whirr of sewing machines in households across the country. It’s the sound of a small homespun cavalry coming to the aid of the NHS and other frontline workers.

Homemade Scrubs Trousers

Dorset April 2020

Independent of governments, voluntary organisations or management structures, thousands of women and men in lockdown have hauled out their machines from under dust covers, found their cutting scissors and set to work to produce scrubs, laundry bags, masks and gowns for care and health workers to protect them and their patients. This has been the real Great British Sewing Bee of 2020.

In Britain more than 37,000 have died so far in the Covid epidemic (May 2020) with a disproportionately high death rate amongst those from minority ethnicities and in public facing jobs. More than 300 medical staff have died and, although figures are still sketchy, we know that there has been a higher than average death rate amongst social care staff and public transport workers. Over 40 transport workers have died in London alone, many of them working without protective clothing and equipment (PPE)

It is anger and concern about people carrying out these key jobs without the right protection that has been the fuel of this movement. So far it has gone under the radar of ministers and managers. who have said almost nothing in the way of thanks for the thousands of home-made items that have come to the rescue of their desperate staff. But if you look you can find the evidence everywhere, from Shetland to Land’s End, and it carries some important messages for our communities and our futures, as well as echoes of the past.

By its nature the Scrubs movement is fragmented, it really does come from the grassroots and has sprung up spontaneously in different ways. I have been part of it, making scrubs slowly and not very well in the garage at home. This isn’t an attempt to describe the whole movement, merely some of the pieces that I have seen. There are many other parts to this and everyone has their own tale. Those stories are important and I don’t want them to disappear without some record, in the way contributions to past crises that have been lost – especially those made largely by women.

Many of the groups were set up in late March and early April as the families and friends saw the piteous lack of protective equipment provided for health workers and care staff. One group, For the Love of Scrubs with over 53,000 members, was set up by Ashleigh Linsdell, an Accident and Emergency nurse in the West Midlands. It acts as a hub for a whole series of other more local groups and offers them advice and patterns, as well as being a place where those who need scrubs can register their needs. There are other groups too, like Scrubs Up, Scrub Hub and For the Love of Gowns. These larger groups have acted as umbrellas for the tens of other more local regional and county groups, like Somerset Scrubs, or just for people sewing on their own.

Free Online Sewing Pattern

For Home Sewers

Covid Crisis 2020

All of these groups have seen some desperate cries for help. Often, the larger umbrella groups have asked hospital managers and care homes if they need anything, to be told no, and then to get posts like this from a member of staff:

“We couldn’t get supplies of anything (no matter how much they were prepared to pay) as it was all funneled to the NHS. That’s totally understandable, I would even give up my own PPE to an intensive care/respiratory/A&E staff member in a heartbeat, as their risk is more than mine I feel, but it did leave private/care homes/dentists, etc very vulnerable. My colleague died, me and my daughter had Covid, along with other staff members. But I came home tonight at 9:45 pm after 3×15 hr days in a row, to 2 pairs of beautifully made scrubs!!! I swear to god, the excitement! ❤️. Best present EVER!!!”

Or these

“Can anyone make scrubs for midwives? Desperate.”

“I am putting out a plea for an NHS Foundation Trust, they desperately need scrubs of all sizes”

“Hi all, I am a secondary school teacher and after today’s briefing, it appears that secondary schools will also be opening for y r10s and 12s on 15th June. Is it possible to request scrubs for my school’s staff?”

“Hi, we cannot buy scrubs anywhere, all out of stock. We are a GP surgery in Canvey Island, Essex”.

The messages from people on the frontline of this trackback over the months of the British lockdown, with no let-up, and tell the real cost of the government’s failure to provide sufficient PPE. Some of those who posted messages asking for help in the early days have almost certainly died, while others will have caught Covid19 and suffered. They needed everything from scrubs to wear underneath PPE, to scrub hats to keep their hair back, gowns and face coverings to protect them, as well as laundry bags to pile everything into at the end of the day and put in the wash, in an effort to prevent the spread of infection at home.

Dr Sarah Wookey in unique

scrubs made from a duvet cover

and sheets. April 2020

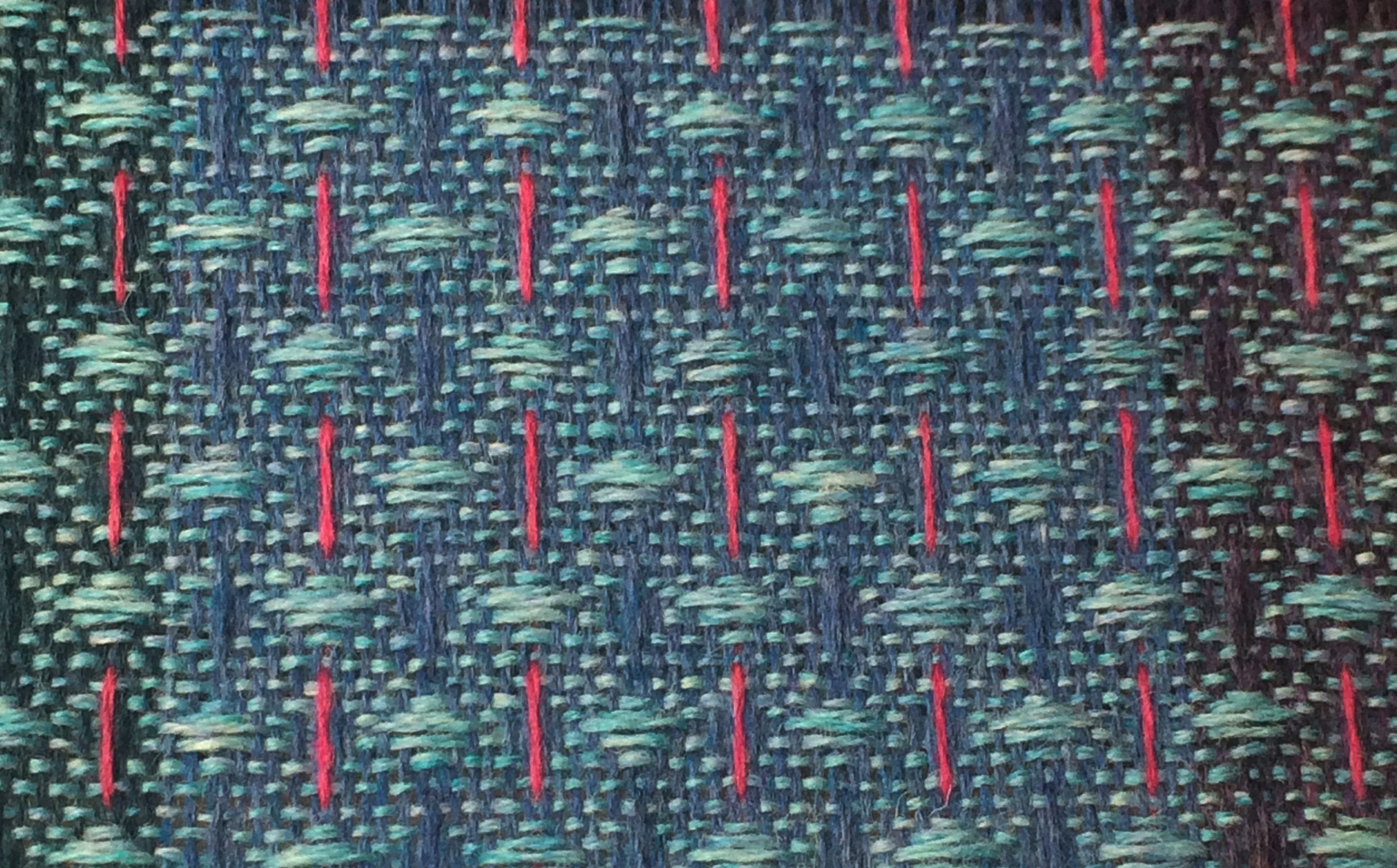

What went wrong needs a proper inquiry, but what went right was the phenomenal grassroots response that came to the aid of organisations and individuals quickly and practically. Sewers have been able to use online patterns posted by professional sewing websites and, without access to the usual NHS polycotton, have made unique scrubs from duvet covers and sheets, curtains, and any spare material. All that is needed is that the fabric washes well at 60 degrees to kill the virus. I even had some blackout material, last used in the Blitz of the Second World War, donated to me for scrubs and laundry bags.

Somerset Scrubs – which I have been part of – was set up shortly after lockdown began in late March. Christine Atkins, owner of a soft furnishings business in Bruton, and Clarissa Love, a student at Bath Spa University, with a child on the COVID high-risk register, were moved by the sight of a nurse crying in her car outside a supermarket and wanted to help. They opened a Facebook page and in 6 days raised £6,500, enough to order rolls of NHS grade polycotton at a discount from a manufacturer in Lincolnshire.

Somerset Scrubs began with one group of sewers – about ten people – and quickly burgeoned to 9 groups sewing scrubs, plus one making laundry bags, and another delivering scrubs and bags around the county. More than a 100 people were involved, able directly and quickly to send the items that were needed, in the right sizes, to local hospitals, care homes, doctor’s surgeries, vets, health visitors, mental hospitals, midwives, charities working with refugees, end of life care teams and, in fact, anyone with a frontline role.

Clarissa says: “So far we have made over 700 sets of scrubs and over 2,000 bags. Some of the people who have been given our scrubs have said how much well-made they are, better than the official ones, which is lovely. I’m lucky enough to see the gratitude of the people who get our scrubs every day, one lady just wrote: “thank you so, so, so much, this means the world to me to know that people are thinking of us.”. We will go on making scrubs until we aren’t needed anymore and all the frontline workers can carry out their jobs safely.”

All of this has happened and been coordinated without anyone meeting face to face. I have communicated almost daily with the sewers in my group, getting encouragement, information, wonderful photographs of ‘our’ scrubs in action, messages of thanks, and new sets of scrubs to make from an efficient network that any business would be proud of. I have only met one member of this group for a few minutes when I collected my first sets of cut out scrubs from a doorstep.

All my experience of how networks function tells me that they don’t work well unless there is a level of trust created by real time meetings. People usually need to look each other in the eye before they will work well together. But not here, these groups have had a tremendous sense of camaraderie, despite the fact that they don’t know each other and come from diverse backgrounds, people who do minimum wage jobs, retirees, teachers, parents, designers and wedding dressmakers, men and women, people who normally have nothing in common and yet they have been able to work fluidly and fast with teams forming and dissolving as the tasks change.

Lenin would be envious! He never created anything half as effective in his mass organising. It has struck me more than once that this has been the perfect model of underground cells, or a resistance movement, with anonymous motorcyclists appearing in my garden to collect or deliver mysterious packages from people I don’t know and have never met. But instead of political change, this movement has had that truly revolutionary device – the home sewing machine – at its centre.

This is the sort of network the British government needs to carry out its community-based case finding and contact tracing, without which there is no safe exit from lockdown. A leader in this week’s (May 26th 2020) British Medical Journal might be describing the scrubs network when it says the network: “Should be low tech and locally driven, with trained staff and volunteers providing boots on the ground, as employed to good effect in Africa during the Ebola outbreaks. It is ironic that the UK promoted and supported the approach in Africa but seems unwilling or unable to adapt it at home.”

Somerset Care Home Staff

in Scrubs made from Undyed

Polycotton Drill – May 2020

Scrubs being made on

a Domestic Sewing Machine

April 2020

Scrubs made for a

Somerset GP’s Surgery

May 2020

Dr Heli Vaterlaws, London GP,

in Scrubs Made by a Yeovil

Wedding Dressmaker – April 2020

It has helped that this has been hyper-local. Somerset Scrubs works across the County, but my small groups work within a few miles of me, and we are often supplying those who are similarly local. I know my local doctor and if she asks for scrubs she is going to get them, as that protects me, my family and my community, and that has been a powerful incentive.

It’s important that the leadership model, where it’s been needed at all, has been servant leadership, supporting and encouraging people, removing obstacles, solving difficulties, and not putting themselves or the organisation first. Becky Owers in Yeovil, furloughed from a job where she says she doesn’t use her brain, has shown exceptional leadership, organising teams of people into raising funds for fabric, finding and printing patterns, cutting out fabric, distributing cut pieces, encouraging sewers, making sure that each set of scrubs has its own laundry bag and is finished to an acceptable standard, getting logos put on them on the other side of the county, and then finally distributing them. She has done this without leaving her house, while home schooling two children.

In Becky’s teams everyone pitches in, does what they can and gets properly thanked for it. I’m not the strongest of home sewers (I’m a handweaver) but no-one has suggested that my scrubs aren’t up to scratch, they have been happily accepted even though my first set had to be finished by Becky as the instructions defeated me! Above all we have shared a common sense of purpose and that has made it easy, our goals have been clearly defined and well understood.

It has also given us a way to make a contribution. It has been difficult for many of us, furloughed from work, to sit at home and do nothing, as the Government ordered, listening to the ever-rising toll of death. But this movement has helped to dissolve the lassitude and torpor we have felt as the days have run into each other. It has taught us new skills, allowed us to bury our anxieties and fears in making something useful, and made us new friends. One scrubs making in the South West commented: ‘It has been humbling to part of something like this, but also it has given me a real anchor in these difficult days.’ Most of those who have taken part have gained as much from their participation as they have given, benefiting from that peculiar magic of doing something with your hands that calms anxieties and dissolves fears. These small acts of solidarity and the love that exists both as motive and reward for this work have had enormous power.

Women in a Hastings Street

Knit for the Troops – 1940

The Queen’s Weekly Sewing Bee

Buckingham Palace, during

the Second World War

I’m astonished that in the 21st century the domestic sewing machine has played such an important role, but it follows the pattern of other, older crises where home production was vital. My mother, now in her 90s, was at school during the Second World War, and along with millions of British women she knitted for the forces: “the wool was ghastly rough stuff, we were issued with it and I wasn’t very good at it. It was khaki, or, if it was for the men on the Arctic convoys, it was white: we knitted scarves, socks, balaclavas and those who were really good at it, knitted long sort of woollen gaiters.” She too was part of a movement of makers, one that enlisted the help of millions of women up and down the country: knitting went on in Buckingham Palace – where the Queen organised and took part in weekly sewing bees with the staff, to the smallest boarding house. Looking at the pictures of women knitting from that time, I envy their ability to sit close together and talk to each other as they knit, seeking reassurance from each other, we have not had that chance. But I recognise in their faces the camaraderie that comes from having a sense of purpose and the ability that making something with your hands has to quiet your fears about the people you love.

Look further back and you see the same pattern of response. Each crisis tends to have a fabric or material that is in short supply, depending on the moment, with small scale domestic production used to fill the breach. In the time of Covid, the material of the moment has been polycotton drill fabric, used by health workers and other key staff across the land as the foundation of their equipment. Suddenly everyone needs scrubs and the supply chains from China are disrupted or not functioning. In World War Two every scrap of silk went to parachutes and at that time most of it was made in Japan, an enemy power. There was little cotton too – it had to cross the Atlantic, to fill the breach makers at home stepped in with wool, which was in plentiful local supply, to make the items troops needed. In the First World War the items in scarce supply were canvas for the wings of planes and wool for soldiers’ uniforms, you can go back even further to Crimean War when there was a world-wide shortage of hemp used to make ropes to tow guns and dock ships. Those would be harder to make in your front living room!

In a lovely book written about the power of myth called ‘When They Severed Earth from Sky” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber and Paul Barber, they write about how mythical stories, the tales that are told around the fireside on a cold night, often have a kernel of important information at their heart. This was the way people who had experienced catastrophic events that only come along every few generations were able to transmit information in pre-literate societies. If you had experienced a tsunami and you wanted your grandchildren and their grandchildren to know about it long after you were gone, then the one way the information could be passed through the generations was through a memorable story.

We need some new myths for our grandchildren and their children, ones that are told over and over again about how in times of need people who have skills and can make things are important. No matter how much we talk the greatest transformation comes from what we can do with our hands – because its the doing that counts. None of us knows what the next crisis will be, or when it will come, and what form it will take, but if we tell the tale of how makers responded in this crisis and in past crises, we will pass on the knowledge that someone with a needle and thread should never be under-estimated, they have the power to save lives and perform miracles.

Resources:

Heide Goody’s excellent Linked In article on the lessons for business from the Scrubs Movement.

V & A Blog: Pandemic Objects: Sewing Machine

When They Severed Earth from Sky – How the Human Mind Shapes Myth: Elizabeth Wayland Barber and Paul T Barber, Princeton University Press 2004.

© Jo Andrews 2020

[ssba-buttons]

About the author

Jo Andrews is a weaver and writer. She has been weaving for many years and at the same time she has been reading and thinking about the influence of cloth and cloth making on history and trade.