Cabbage & Mungo:

Savile Row, in the heart of London, has been at the centre of high-quality men’s tailoring for 200 years. It has supplied handmade suits, from the finest woven cloth, to film stars and royalty, to statesmen and sportsmen. It has a reputation for quality and excellence second to none. Now it is embracing recycling, and it seems, its top-end clients are happy to pay for it.

It’s incredibly rare to find a recycling loop like this one – especially in textiles – where the waste is turned into quality new material to be used by the same workshops that created it in the first place. This episode tells the story of how this is happening and follows the journey that turns tiny bits of fabric that would previously have been binned, into new bespoke garments, ones that come with great credentials and an interesting story behind them.

Along the way Haptic & Hue gets a privileged glimpse into the world of Savile Row tailoring – the training and the standards that need to be maintained from start to finish to produce a garment that may well last a century or more.

The people you hear in this episode are:

Leon Powell: Senior Cutter at Anderson and Sheppard. Their website is www.anderson-sheppard.co.uk, and their Instagram is https://www.instagram.com/andersonandsheppardbespoke/

Su Thomas of the Savile Row Bespoke Association, at https://www.savilerowbespoke.com/ . Su has also set up a new website for the recycled cloth initiative called Ecoluxe100. You can find out more at https://www.instagram.com/ecoluxe100/

Richard Anderson of Richard Anderson Ltd. His website is at https://www.richardandersonltd.com/ He has also written a good book about his time on Savile Row which I really enjoyed. It’s called Bespoke: Savile Row Ripped and Smoothed, and you can order a signed copy directly from Richard at https://www.richardandersonltd.com/product/bespoke-ripped-and-smoothed-book/

John Parkinson is the Founder of IINOUIO which stands for It Is Never Over Until It Is Over. You can find out more about the yarn he produces at https://www.iinouiio.com/ . And you can hear the wonderful history of Shoddy and Mungo in Haptic and Hue podcast #24 called Shoddy: the Once and Future King.

Sam Goates is the founder of Woven in The Bone. https://www.woveninthebone.com/ . She makes artisan cloth for the tailors of Savile Row, and also on commission for a number of special orders in the UK and abroad. You can see much more about the processes needed to weave quality cloth on her Instagram https://www.instagram.com/woveninthebone/

The companies that took part in this initiative are Anderson & Sheppard, Gieves & Hawkes, Henry Poole & Co, Richard Anderson, Dege & Skinner, Kathryn Sargent, Holland & Sherry, Arthur Sleep, and Pickett London.

Wool Month is an initiative of the Campaign for Wool, which is a global campaign with events and activities around the world. The Campaign will have a pop-up at 30, Old Burlington Street London W1S 3AE, from Wednesday, October 4th.

Savile Row in the 1950s

Leon Powell, Senior Cutter at Anderson and Sheppard and their wool offcuts bag

Front Room at Anderson and Sheppard, Savile Row

The Busy Cutting Room, Anderson and Sheppard, Savile Row

Cutting in Progress, Anderson and Sheppard, Savile Row

Customer’s Patterns, Anderson and Sheppard, Savile Row

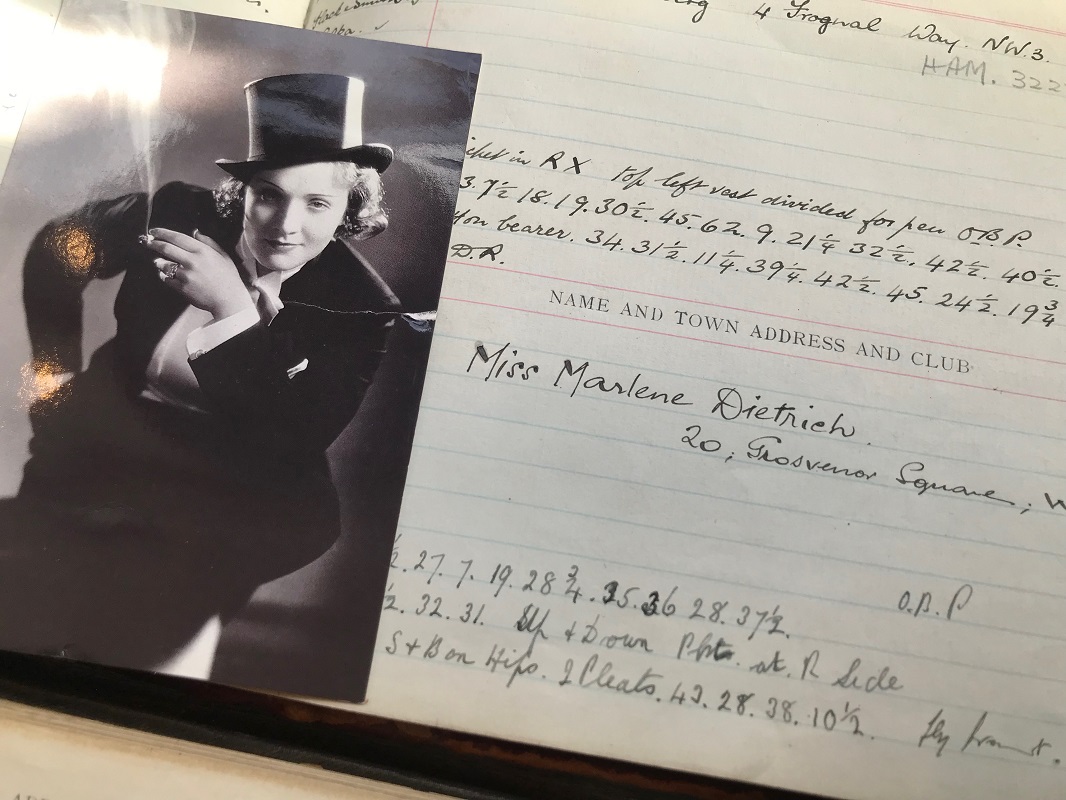

Marlene Dietrich’s Order, Anderson and Sheppard, Savile Row

Tools of the Trade, Anderson and Sheppard, Savile Row

Instructions to the Tailors, Anderson and Sheppard, Savile Row

Making a pocket, Anderson and Sheppard, Savile Row

Recycled Fabric, Ready To Be Re-cut.

Oliver Spragg with the jacket he tailored and Leon Powell cut from the recycled fabric, Anderson and Sheppard, Savile Row

Detail of jacket, Anderson and Sheppard, Savile Row

Su Thomas – Savile Row Bespoke Association

Richard Anderson with his daughter Molly – his apprentice – behind him

John Parkinson on the left

Shoddy being fed into the machine

Wool waste becomes new yarn

The Home of Woven in the Bone, Buckie, Scotland

The View from Woven in the Bone, Buckie, Scotland

Woven in The Bone Headquarters, Buckie, Scotland

Weaver Sam Goates and Her Looms

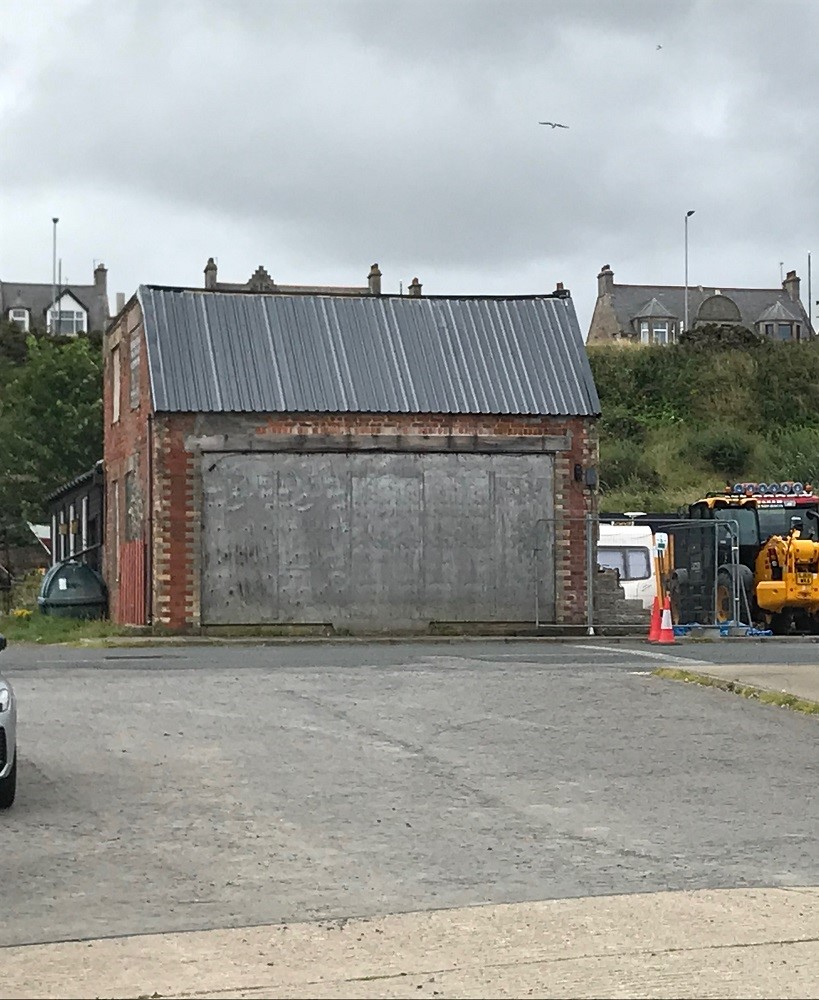

Recording this podcast at Woven in The Bone in Buckie, Scotland

Script

Cabbage & Mungo: How the Bespoke Tailors of Savile Row Started Recycling Again

JA: Savile Row is one of those very special places that makes London….well London. It’s a shortish street in the heart of Mayfair, just west of Regent Street, and for two centuries it has been home to a number of deeply skilled cutters and tailors producing some of the finest made to measure men’s suits in the world.

London used to be full of these little villages. Every craft had its corner, sadly few of them have survived. But Savile Row is still there and to this day the little streets in this area are busy with cutters and tailors in workshops right here in the centre of the city.

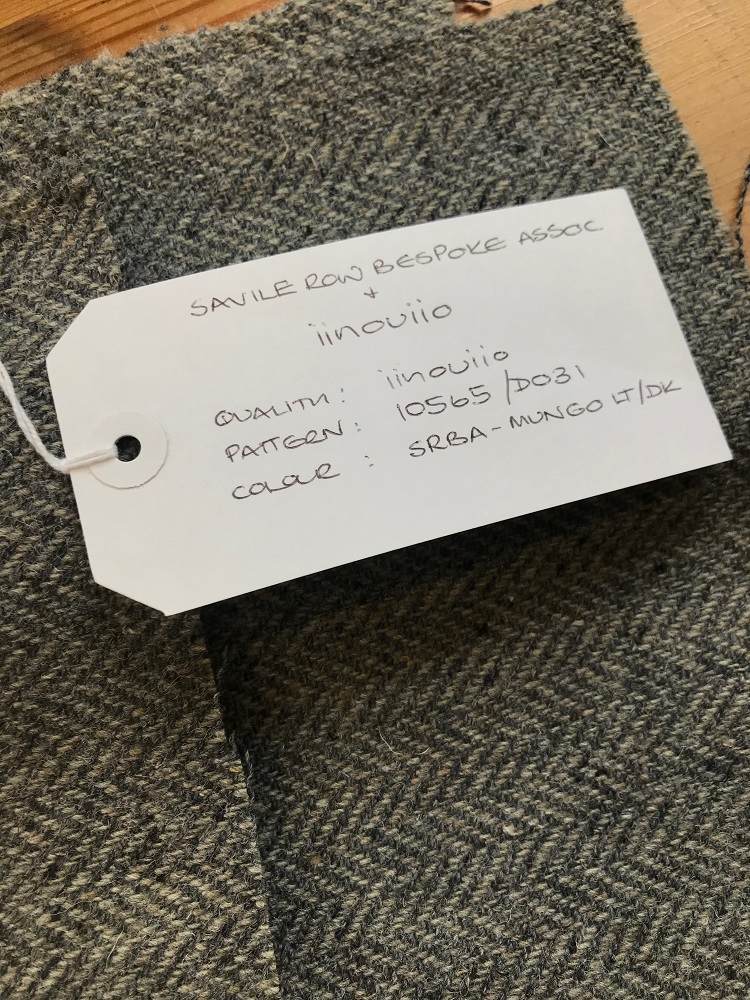

October is wool month in London, hosted by the Campaign for Wool, which has done so much to promote the revival and benefits of wool. And if you find yourself on the Row this month take a close look at the windows – a number of them are showing different handmade garments all cut from the same interesting, grey marled herringbone tweed. There’s a gentleman’s sports jacket, a ladies double breasted jacket, a two-piece men’s suit, bespoke shoes and a lady’s waistcoat, as well as a number of different accessories. This fabric and these garments are unique, they have been made from the floor sweepings and the offcuts of the Savile Row tailors, which have been recycled into cloth and for the first time in history, tailored back into quality garments to be sold to bespoke customers. Even more extraordinarily it seems that some of Savile Row’s high-end customers are happy to pay well for recycled fabric.

Leon: I think a lot of customers will really enjoy the story. I think, in today’s society, people want this. People even with normal cloths want to know where it came from. People want to know the background. So, I think in this day and age, it’s part of the story. So yeah, I think if people know this is available, know the background, there’s going to be certain people who think, wow, that’s fantastic. I like that idea. That’s really kind of forward thinking and clever. This straightaway was such a success and we were so impressed with the cloth. We have commissioned a length for ourselves straight off. The romance, the idea, everything about it, the crafts all coming together, all doing this is just fantastic for the industry.

JA: That’s Leon Powell, a Senior Cutter on the Row who has played an important part in creating this very special cloth. And my name is Jo Andrews, I’m a handweaver interested in what fabric – and the skills that go into producing and shaping it – tell us about ourselves and our societies.

This episode of Haptic & Hue is about the efforts of the tailors of Savile Row to recycle their own textile waste into cloth of such quality that it can be re-sold to their high-end bespoke clients. It’s a tale that starts and ends in London, but takes us to Yorkshire and onto the North East coast of Scotland as we follow the transformation of floor sweepings into brand new garments that will sell for thousands of pounds.

Anderson and Sheppard is a Savile Row tailor that has been in business for nearly a 120 years. It’s a civil tailor – that is it didn’t start life, like some of the older houses on the Row, making military uniforms. It’s known today for its more relaxed tailoring, and indeed the front shop looks like a rather wonderful gentleman’s club, complete with leather sofa and soft lighting. They have kept a handwritten record of every customer who has passed through the doors. In the pages of the old order books you can find the measurements and signatures of the Hollywood stars Cary Grant and Gary Cooper who had their suits made here, and more surprisingly those of Marlene Dietrich, who was also a customer of the gentleman’s tailor. Here’s Leon:

Leon: I’ve been at Anderson and Shepperd for 21 years. I started as a coat apprentice learning to make after coming out of university. An apprenticeship as a coat maker would last four to five years. But after about two and a half years, I was asked if I’d like to come into the cutting room and learn to do the cutting side of the production. So, I spent a number of years as a, what was then called an under cutter to a senior cutter. But today we call them apprentice cutters. The terminology has just evolved and changed over time. And then for the last probably about 10, 11 years, once they deem that I am capable, they allow me to start measuring customers up and doing fittings and cutting the patterns.

JA: Leon works in a busy back room, where people come and go all the time – phones ring, boxes arrive and depart, different groups cluster around the long tables for meetings and discussions. No-one sits down much.

Leon: So, the room you are in at the moment is what we call the cutting room. So, this is where the coat cutters and trousers, cutters will come cut patterns. After taking measurements, we’ll also strike in, that’s where we lay the cloth out using the patterns, lay the patterns on, and then chalk round the patterns and fill out all the details. And then we cut the garments. So, we all work on about three-metre-long boards. As you can see, Sunny cutting a pair of trousers, a cloth is laid out, it’s all struck in by chalk. Once it’s matted directly onto the cloth, we cut directly into the cloth. We don’t make toiles in that sense. We always work on the live garments, on the live cloth from the very beginning.

JA: The confidence with which they handle and cut into this expensive cloth is extraordinary to watch. It’s a hard thing to do:

Leon: It is and it isn’t from a point of view that we’ve done it so many times. As an apprentice, as an under cutter, as you’re training before you actually start cutting the cloth, you’ve done it over and over and over again. So, it’s like muscle memory. It’s something that is continuously kind of drummed into us from a very, very beginning. So even before you cut on the cloth, you’ll have practiced numerous times.

JA: Ranged at each end of the room is a wall of thick brown paper on hangers. These are the cutters’ libraries:

Leon: So the brown patterns behind us are customer patterns. So, each time a customer comes through the door a new customer comes in, we will do measurements. So, for myself, I will take a set of measures, then one of my colleagues on the trouser department will come in and they will take measurements from those measurements and configuration, which we also take. The configuration is the gentleman’s posture. The way he stands, this is very important as well. So, from all these details we take, they are noted in our measure box. From that, we cut each customer an individual pattern. We start off with usually cutting a single breasted, which is kind of the foundations the building blocks. If we need to cut. So, for myself being a coco, I will cut a single breasted, even if they want a double breasted or an overcoat, we’ll cut the single-breasted jacket to start off with. And then it’s adaptations from there onwards. So, we then develop and we’ll cut the next stage and build it up. So, the patterns you see behind us are what we call existing customers. So, some of these patterns go back to the early sixties, 1960s. And these are still customers that are coming to us to this day. So, and then obviously as we go through and towards the bottom end these are the newer customers. So, some of these patterns could be just a single-breasted jacket, and trousers. Some of them could have single breasted, double breasted dinner, jacket patterns, overcoat patterns, morning coats, dress wear. So there could be some of the customers, there could be several patterns to one name up there.

JA: And yes, even people who order Savile Row suits change shape over the decades but that is all catered for.

Leon: Well, people do change and that’s why we have the original patterns and they evolve. So, if a gentleman, over time, a gentleman may ease configuration, his posture may change. As a gentleman sometimes gets older, they might start to go over a little bit. So, all this is counted in. Someone might lose weight or someone might gain weight. This is always, it’s an evolving process. We’re always looking at that. We’re always checking that. So, the patterns evolve as well to the same proportions of as the gentleman.

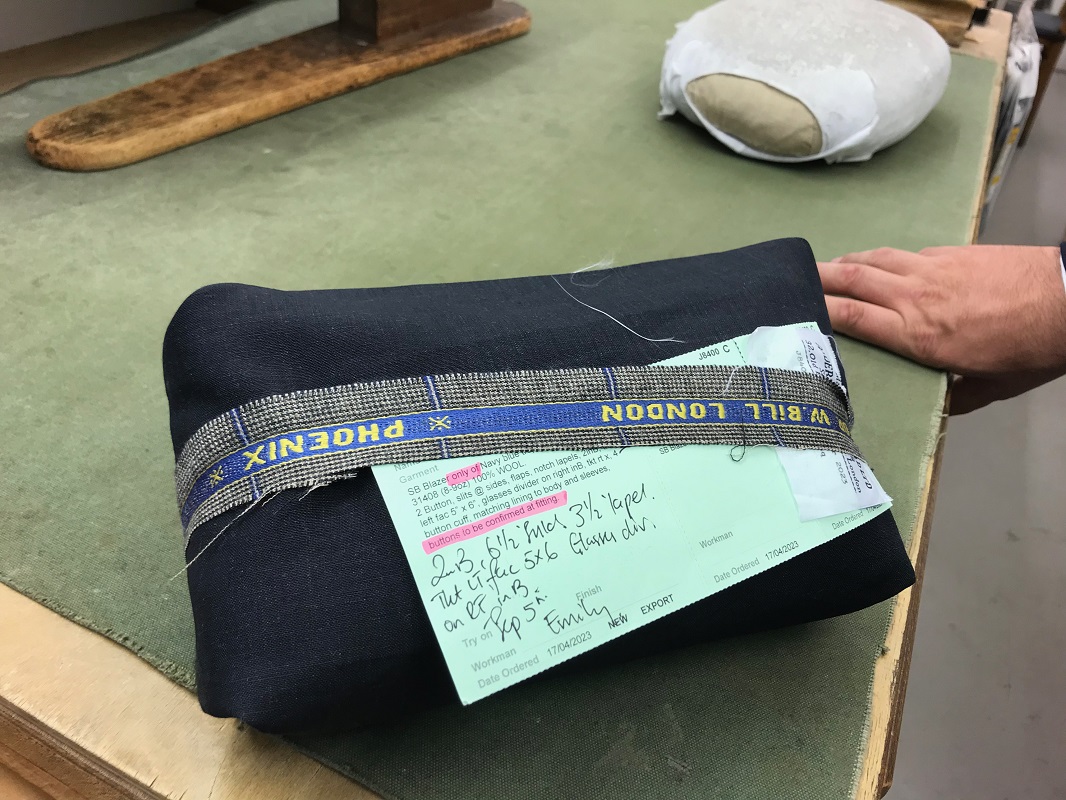

JA: I love the tactfulness of the language. Once Leon has cut his pieces, they are folded carefully into a small bundle and small card of instructions are attached – these look like a complex code to you and me, but they are very precise instructions to the makers downstairs, each of whom specialises in coats, waistcoats or trousers. They stitch the cloth together carefully – reinforcing with beetled linen where necessary and turning out perfect seams and pockets, beautiful lapels and linings.

The time it takes the cutters and makers to qualify and the specialised skills they have are an unusual thing in a world of just-in-time deliveries. They are doubly unusual in the age of throwaway textiles. But this is a place where the price customers are prepared to pay for the quality of the end product and the reputation of the tailors means that the knowledge survives.

Leon: I’m very fortunate. I love the job I do. I think the gentleman and the ladies in this profession, they want to be here. It’s not something they’ve stumbled in. Every one of the gentlemen in this cutting room wants to be a tailor, wants to be a cutter, want to be at Anderson Shepperd. I’m sure it’s the same for other tailors down the road. And in the city and worldwide. You don’t kind of stumble into this profession. It’s kind of a profession that you want to do and you kind of aim for it. And at the level we’re at, you definitely got to want to do it because there’s competition. Like any top industry in the world, you want the best people, the people that are excited for it, enthusiastic about it, who have got a passion and a love for the craft.

JA: But a couple of years ago there was someone watching these master craftsmen and women who thought something could be done better.

Su: I got really fed up of seeing the tailors in Savile Row, throwing away really high quality, a hundred percent wool waste. When I say throwing around, I mean in the bin. So, I started talking to some of the older master tailors who said, you know, we used to do this. We had a guy that used to pick the waste up, shoddy up, and we had the machines that, you know, in the UK that could break it down. So, I thought, gotta do something about this.

JA: Su Thomas has managed the Savile Row Bespoke Association for many years, developing the programme that protects the craft and trains the next generation of craftsmen and women. The first thing she did is ask the tailors to start to collect their waste again:

Su: I had to give them recycling bags that didn’t look anything like the current recycling bags that they put paper, et cetera in. So, I had some Hessian bags made. And one of the things about Savile Row is, particularly some of the companies that have royal warrants, in order to keep that royal warrant, sustainability is a really important box that has to be ticked. So, it wasn’t very difficult to say to them, I want you to collect all your hundred percent wool waste for me, and I will centralise and store it. So getting the tailors to collect the waste actually was the easy bit, really.

JA: And this wasn’t a completely new thing for the tailors, as Leon says there’s a memory in the trade of a time when the wool waste was collected.

Leon: Back in the day someone would come and collect that and we’re talking 30, 40, 50 years ago. That hasn’t happened for a number of years, unfortunately. That just kind of gets, even though there’s only a small amount of, it seems to be cast away. So obviously recently we were asked if we could start saving some of the scrap pieces just of wool, of course. Because obviously we cut linens and silks and they didn’t want us to mix it up. So, we have to be selective in what we’re putting aside. So, we started gathering some of the kind of what we call mungo. Instead of it just being cast onto the floor, we started to save that for someone who was interested in trying to develop a process where it would be all stripped back to raw fibres.

JA: And there’s that lovely word mungo, which is what the Savile Row tailors tend to call wool waste, the other word they use is cabbage. Mungo, technically is woven wool waste for recycling, while its close relative, shoddy, is knitted wool waste.

It took time to fill those hessian bags. Savile Row may be a luxury industry and a handmade suit may cost you around five or six thousand pounds – depending on the tax – but it’s not a wasteful trade. Richard Anderson has been a tailor on the Row for nearly forty years and runs his own establishment.

Richard Anderson: Generally, our main customer is a gentleman in, in his mid to late fifties, CEO you know, financial guy. But we do have a real crop of younger customers, late twenties through to their, into their thirties. As I say, sportsman pop stars, actors, all that.

JA: Richard says his suits are sustainable:

Richard Anderson: I think in the tailoring world, we are really quite good at that. But I think also bespoke clothing, it’s far away from this throwaway fashion thing because each bespoke suit takes 60, 80 hours man hours to make and they last for decades. They’re very often passed down from generation to generation. I’ve got three garments upstairs at the moment which have been passed down from father to son. So, you know, we are expensive. I mean, the Savile Row suits are expensive, but they’re great value for money because of the work that goes into them and the, sustainability that you know, goes along with that. there’s virtually no wastage at all.

JA: Each striker works out the way in which he or she can make the best use of the fabric.

Richard Anderson: So, each customer has his own individual pattern. You know, I’ll measure you, we’ll cut a pattern to your measurements or the customer’s measures, and then those patterns will be put down in a way which is very economical. There shouldn’t be any waste because obviously this fabric is very expensive. You don’t want to be kind of ordering an extra meter or half a meter or even 10 centimetres of cashmere or vicuna that you don’t need. So, if the striker is worth his weight is worth his salt, he’ll work out the length to the best most economical way.

JA: Even so after six months Su Thomas had a number of bulging sacks of Mungo and a storage problem – where was she going to put them while she worked out what happened next?

Su: Well, initially, believe it or not, in the car park underneath one of the buildings, you know, so I would get the trolley, you know, from Anderson and Shepherd and say, can I borrow your trolley Anda, you know, and on the bag in the car park, I stored it, and actually, it’s still in Savile Row. It’s actually in a different place in Savile Row at the moment. So, I stored it underneath the car park, which at the time was very handy.

JA: Su’s problem was that she was trying to re-invent a system that had been there in the past, and worked well in an age when fibre and cloth had value, before it became cheap and over-abundant. We told the story of how rags were carefully gathered and sorted from all over Europe and recycled it back into yarn in Britain in episode 24: Shoddy – the Once and Future King, and how that trade died out in the UK at the end of the 20th century.

To add to Su’s problems she was trying to re-create this supply line at the time of COVID. And she didn’t just want to make ordinary recycled cloth out of her mungo, cloth that gets sold at lower prices to make clothing at the cheaper end of the market. Su wanted this fabric to be special – good enough for Savile Row itself to tailor it back into suits. She wasn’t asking much. But she found her shining knight on horseback in a very down-to-earth Yorkshireman whom we have heard from before. John Parkinson describes himself as an old ragger. A man who grew up in the shoddy trade before it died and for the past few years has been doggedly working to re-establish new shoddy machinery in Britain that can take both knitted and woven wool waste: shoddy and mungo.

John Parkinson: I think the cliff hanger on the last podcast that I did with you was that we got the machine, it was built. We got a research and development grant, but the mill that was gonna house it had to go backwards on the deal because they were having troubles with their insurance, and we’d nowhere to put the machine. So, talk about drama, you know, we were eight, nine months, we’d talk to Su, we’d got all this sorted and we’re ready to start to do this thing, and all of a sudden, we’d no-where to put the machine. We’ve got a machine in storage and getting charged storage charges. And for 10 months we’re running around the trade trying to find a mill, and everybody was cheering us on, but for the one reason or another, they didn’t have the space and they were concerned about their insurance people and all that kind of stuff. We had nowhere to put it. And the project was in real jeopardy of not going ahead.

JA: At the last minute, John did find space for his machines at Camira Fabrics in Huddersfield. Camira exports bus and metro seat fabric worldwide, much of it made from wool, so that was good fit. Once John had his line up and running, Su drove her hessian sacks up to him in Yorkshire and John set his brand-new machines going to pull the fabric apart:

John: Yeah. And that’s the term we use, pulling. So, you know, the room, we call it the pulling shed, which I think is a great, great name for a nightclub, but it’s not a nightclub <laugh>. It’s where we do the, it’s where we do the work. And it, yeah, that’s literally it, it’s rollers that hold the materials tightly with a big drum. We call it a swift, with teeth on that pulls the fibre out of the, of the material that’s there. And so, the modern term is opening it up, some people would say shred, and it’s easier to imagine. But yeah, it’s pulling the fibres out of the construction, whatever that is. It can be threads, it can be tailor clippings, it can be post-consumer jumpers, throwaway jumpers, but in this case mostly fine worsted cloth.

JA One of the joys of processing cloth in this way is that there is no bleaching or dyeing, it is sorted into different colours by eye, and this is where the skill of a shoddy man like John comes in. He has to understand what he has, how he can mix it and what might need to be added in new wool to create interesting and usable yarns that can be woven together. Bear in mind that the waste John was starting off with was men’s suiting so that limited his choices.

John: We sorted just two colours, ’cause we didn’t have enough waste just to make lots of different colours. There wasn’t enough quantity. So we did a dark and a light shade. We got the dark shade and the light shade that we mixed with a GOTs certified organic British lambswool. So, trying to keep the provenance there. That’s undyed. So, the colour comes from the sorting into the two different types, the two different colours, and the colour that was originally on the waste in its first life. The new wool hasn’t been dyed, so it’s a hundred percent undyed product. And we spun the dark and the light. And then that was able to get woven into a cloth

JA: So Su had her yarn. Now she needed to send it somewhere special to be woven – so she despatched it 600 miles north to a woman who comes close to being revered by some of the tailors of Savile Row: here’s Leon Powell:

Leon: Some of this was given to a wonderful lady in Scotland called Sam Goates, who’s basically got a small kind of artisan cloth making company who we’ve been working for a number of years. So, it was arranged that some of it would be woven up as a sample piece. And she works on the old l foot, treadle mills and some real old machinery. It’s absolutely fantastic what the work she does. She’s a complete utter maverick inspiration when it comes to kind of keeping this old skill and trade and going. And what she’s produced is something quite wonderful.

JA: Buckie on the North East coast of Scotland is about as far from Savile Row as you can get. It’s a tough fishing port where there’s the same sense of pride about their work as there is on Savile Row – but here they tend to care more about the cut and durability of their waterproof oilskins rather than their suits. On the road right down by the docks where the trawlers come in to unload, there’s what looks like a derelict shop. Around by the side door is a small notice that says Woven in the Bone and from inside you can hear the magic sounds of foot powered treadle looms and flying shuttles. Haptic and Hue was there this summer, with John Parkinson, who had come to see what Sam Goates had made of his yarn:

Sam: So initially, as, as I would always do, I, I did a sample on a table room first. Because that way you’re, you’re sort of really close with the yarn and, and you’re getting, getting a good handle of how it feels. And yeah. So it was a perfect sort of precursor to what we got for bulk. And yeah, the, the only thing that came up was I did find that it was, it was, it hadn’t been steamed. And, and another with other looms, it might not been a problem for like a rapier loom, but because we’ve got the shuttle looms, there’s a, there’s a point in the, in the cycle where the shuttle’s coming back in from one side, the, the yarns being pulled out and as the, as the shuttle comes back in towards the cloth, through the fell, that the yarn has an opportunity to, to run loose. So, it was, it was sort of over twisting. So, you know, those, that’s exactly why you do samples to sort of work out, , what, what things needed to be done. So, John got, got it, steamed hey presto, no problems at all. It was great.

JA: It was the first time Sam had worked with Mungo:

Sam: Absolutely. Yeah. No, it was great., it was lovely to work with, absolutely fine. it has such a lovely quality, like so many what the UK’s famous for with fibre-dyed woollen yarns, it had all those qualities. It’s got the little flecks of colour, you know, the, the light would change through the day and, and you’d, you’d sort of notice different colours come up through the yarn. So it has bucket loads of character. It’s lovely.

JA: She and Su chose a simple weave designed to show off the colour contrast well:

Sam: We went straight for the herringbone. We did speak about it. We wanted just something pretty classic. We didn’t want to do anything too fancy. And, and everybody loves the herringbone and it, and I think herringbone, you know, it’s a classic eight by eight herringbone. It, it shows off the sort of speckled, the marled nature of it, the melange colours that, that, I mean, it’s something everybody loves and, and I must say people really love herringbone. So, you know, it was a, it was an easy choice.

JA: And Sam says if she didn’t know this was made from mungo – she probably wouldn’t have guessed:

Sam: I don’t think I would because, and, and I suppose I’ve been, I’ve been in the trade for far too long, 30 plus years. But I’ve never worked with that before. So, I guess, I have heard about it, heard about the shoddy trade, mungo trade but never really knew exactly what that was. So, no, I would, I wouldn’t have known. I feel so lucky to have been involved in this, I mean, it really ticks all the boxes of, of believing, you know, in times when the news can be quite daunting. It, it’s really nice to feel that and see tangible evidence of the things that we can all do to make good and, and to see something lovely come out of it. It’s really good.

JA: It’s a lovely story, but the acid judgement in this is that of the tailors themselves – was this something they could take seriously as a fabric or was it just a gimmick? Here’s Leon.

Leon: It’s absolutely fine. It’s lovely. It’s cut. It strikes well. it’s just soon as we saw the cloth originally I was like, I’ll be honest, I was quite shocked, pleasantly shocked in a good way. I was like, wow, this is kind of, I dunno what I really expected, but what we got was something far superior than I personally expected. And you’ve got to just look at what you get at a time and go, wow, this is, this is good. This can be used. This isn’t like just like, oh, we’re trying to do something. And it kind of, it’s kind of worked. It hasn’t worked. It has worked. And like I say, and this is a first attempt or not attempt, this is a first batch. It’s only gonna get better and better and better as people kind of learn to handle it a little better. And do might think, all right, we do this slightly different. Tweak things, improve things. I believe it’ll only get better.

JA: Richard Anderson in his shop around the corner also likes it.

Richard Anderson: I thought it was very good. It had a lovely kind of different colour or hue to it, which was, which was different ’cause it, it was predominantly grey, but there was a, little brown and sort of blue hues in the fabric as well, which I thought was interesting. So, it did look a kind of, although it’s a classic pattern, there was a kind of interesting colours, hues in there, which obviously comes through all the different fabrics that we collected. I thought the weight was good. The fabric was really quite dry. So yeah, you think it’s gonna be a substantial bit of cloth that’s gonna make up, well, quite frankly. And we’ll see, you know, ’cause I’m gonna be cutting it next week. I’m probably going to make a lady’s jacket out of it. Maybe double breasted. But yeah, we’ll see actually. Yeah.

JA: Each of the tailors who had collected mungo and cabbage for Su were offered yardage to make up in a new garment to put in their windows to celebrate Wool Month. When I was at Anderson and Shepperd, Leon Powell had already cut his fabric into a gentleman’s jacket and one of the workshop’s apprentices, Oliver Spragg, was tailoring it into a finished garment. Leon showed me how the jacket was being put together.

Leon: This is what we’d call a baste. So, it’s kind of the initial structure of the jacket. We obviously, we’ve got the lapels pad stitch, we’ve got the pockets in, we’ve got the canvas in, but the facings are not on. So, if we have to make adjustments to the front edge and do alterations, we can strip this down and everything can be kind of recut. This will be taken, but it’s gone on the mannequin. This is a display piece. So, this has gone onto the mannequin. I’m incredibly happy, a few little tweaks but this is a proven pattern. It is what I’ve been using for several years as the kind of Anderson Shepperd stock pattern. So, it’s made up very, very nicely. We’ll take it to a finished stage over the next couple of weeks.

JA: And the million-dollar question for any Savile Row cutter? Would you wear yourself? Leon would and he wouldn’t:

Leon: Not the colour <laugh>. And I don’t mean anything detrimental without that. Yes, I would, but I tend to be more no colour. It’s, this is a grey, this is a lovely grey herringbone. Unfortunately. I’m a bit pasty and pale. It washes me out. I tend to wear more blues, the do it in blue all day long. <Laugh> not a problem.

JA: Neither Leon nor Richard were in any doubt that this fabric will sell, and sell well. They know they have customers who will enjoy the story and be prepared to pay for it. But therein lies a problem, as this was a trial run. Su proved that it can be done and each of the shops that took part will have a made-up garment in their windows for Wool Month. But as Richard says – that leaves him with a difficulty.

Richard Anderson: So the downside is we make one jacket from it and someone, my customer goes, I want one of those. And you, you haven’t got it. So, it’d be nice to have a if, if this does work, if this did work from a commercial point of view, I think, you know it’d be nice each house to invest into 10 jackets worth or something like that. Because you would sell them. So by making one jacket, I’ll certainly have, if it makes up well and it looks good, then I can guarantee I’ll have some guy or or woman say, can I have one? And then we’ve gotta say no because you know, there, there’s none left.

JA: Su knows this and there are plans in hand to produce more cloth – but the first thing she says she had to do was to prove it could be done in the first place.

Su: There’ve been many ups and downs, but one of the things that was really important about the project was to try and evidence that it, it could be done and a high-quality cloth could be produced that could be made into a garment again. And one of the things that was very important was working with Campaign for Wool to promote not so much the garments or the garments that will be beautiful and be made by bespoke tailors and look glorious, but it’s really about the story from start to finish. And so, one of the things that I, we all want to promote is you know, the story of evidencing that it can be done.

JA: For John Parkinson, the man who has shoddy in his blood, this is much more than just a single story, its more even than a being a small contribution to arresting the appalling waste in textiles, it’s about keeping the knowledge and skills alive too, that he believes have a role to play in the future of all our economies.

John: So, from, from things that for too many decades have been dropping onto cutting room floors and put into bags and thrown away and not reused. Between all the people that’s been involved, we’ve now got a beautiful piece of cloth that’s ready to start a life all over again. This can make beautiful new garment all over again. And they’ll last for a long time, I hope. And, you know, the classic designs that Savile Row do or any, any other designer that might want to think about keeping the garment for a long time, but there’s nothing to stop this when this has got to the end of, of its life, coming back through, being mixed with some new stuff and being included again. So the whole thing just can keep rolling and rolling wherever you’ve got new mixed with old and the right kind of new, new wool put with it. And that’s the full circle, especially when we can offer the cloth back to tailors and other people that the waste came from. That’s the kind of full loop, that’s the full cycle. And everybody taking responsibility for that waste, not just ticking a box. Oh, it’s gone. Somebody picked it up, a waste man. It could be incinerated for energy or it could be whatever, neither of which is great. You wanna keep the value in it, as well as the craft. So we make a lot of play out of the environmental benefits. There’s also the heritage, the craft, the knowledge of setting the machines and knowing what to mix with it and all that kind of stuff that were a big risk had dying out. There were no traditional, what we call shoddy manufacturers left in the country. So, it’s a double-edged, at least a double-edged thing as well. Environmental things, And also a protection of an endangered species, which is the shoddy industry.

JA: And that knowledge is worth having. It’s almost as if the age of shoddy has arrived. For centuries this has been a despised industry, looked down on by people who preferred to buy new when they could. But today shoddy and mungo, if they can be responsibly revived, are an important part of the answer to textile waste, and if somewhere like Savile Row can do it, and their customers want to buy it – there’s no reason why it shouldn’t sell well as a quality cloth elsewhere too.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Haptic & Hue, and a huge thank you to everyone on Savile Row for being so welcoming and letting me understand what they do. It was a huge pleasure to travel to Buckie to see Sam Goates in her weaving shed and to meet Su Thomas and John and Linda Parkinson, thank you all for making this story come alive.

If you would like to know more about the speakers, see photos of them and their workshops, see the famous Savile Row mungo being collected or woven, please have a look at the page for this podcast at www.hapticandhue.com/listen. It is episode number 43.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews, and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a member of Friends of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast independent, and free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you extra content every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted Bill Taylor and me.

We’ll be back on the first Thursday of next month with another Textile Tale- this time it’s something I’ve thinking about for a long time – how do we pass on sewing skills, who teaches us to sew and why does it matter? We’ll be looking at how people were taught from Britain to Brazil and beyond, join us then for another episode of Haptic & Hue.