Episode #53

Jo Andrews

Flax is a fibre that looks back as well as forward. Like no other yarn, it is the ancient fibre of civilisation. Linen has walked the long centuries alongside mankind. In Europe and Western Asia, its cultivation reaches back thousands of years to the beginnings of human settlement and farming. It clothed the pharaohs of Egypt in life and death, it powered the ships of ancient Greece and Troy, it is mentioned more than 80 times in the Old Testament. This is the fabric that wrapped the Dead Sea Scrolls to keep them safe down the centuries.

Join us this month as Haptic and Hue travels to Ireland, once the undisputed centre of the world’s linen processing industry to see what it is making of the great flax revival and how Irish linen is faring.

Notes:

Fiona McKelvie can be found on Instagram as @mcburneyandblack and her Etsy site, selling Irish linen is at Mcburneyandblack.

Helen Keys and Charlie Mallon are at Mallon Linen. https://mallonlinen.co.uk/, where you can buy Irish flax for hand spinning. Mallon Linen are also on Instagram as @mallonlinen

Ciaran Toal is Keeper of Collections at the Irish Linen Centre and Museum in Lisburn. https://www.lisburnmuseum.com/ . The Centre is also on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/lisburnmuseum/

Duncan Neil is Creative Director of William Clark and Sons. You can find them at https://www.wmclark.co.uk/ and see pictures of the wonderful beetling machines at https://www.wmclark.co.uk/beetling

Mario Sierra runs Mourne Textiles, which can be found at https://mournetextiles.com/ They are also on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/mournetextiles/

One of the best books on Linen is called Linen/Flax Fabric of Civilisations. It does exist in English but appears not to be for sale, you can, though, buy it in French from Actes Sud who are distributing it.

Another source of information is the European Alliance for Flax-Linen and Hemp https://allianceflaxlinenhemp.eu/en which has a lot of detail and research about the current standing of flax and hemp crops in Europe.

Fiona McKelvie. Photo By Si

Charlie Mallon Gathering Flax, Mallon Linen, Moneymore

Helen Keys and Charlie Mallon Pulling Flax at Mallon Linen

Flax Waiting To Be Dried and Retted, Mallon Linen. Photo Fiona McKelvie

Retted and Rippled Flax, Mallon Linen

Rebuilt Scutching Turbine at Mallon Linen

Scutched Linen

Mario Sierra, Mourne Textiles

70 Year Old Wet Spinning Machine Mario Sierra is Renovating at Mourne Textiles

Old Damask Point Patterns at the Irish Linen Centre, Lisburn

Beetling Mill in Action, William Clark and Sons

Ciaran Tole – Keeper of Collections, Irish Linen Centre, Lisburn

The Beetling Mills, William Clark & Sons

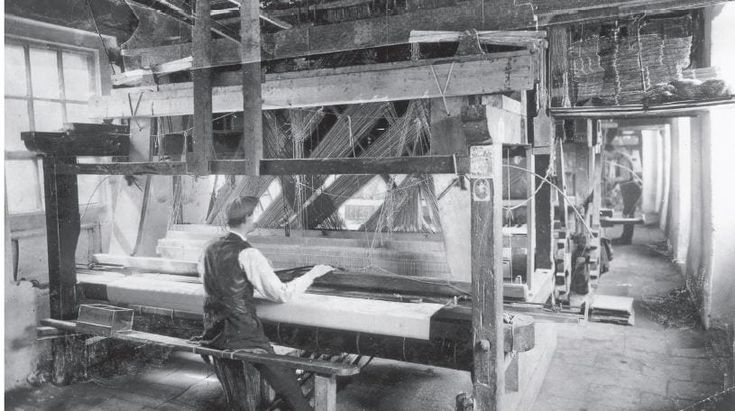

Hand Weaving Damask on a Jacquard Loom, around 1900 at Coulsons of Lisburn, Photo from Irish Linen Centre, Lisburn.

Script

Flax is Back! The Great Linen Revival

JA: All over North-Western Europe the past few years have brought the mid-summer sight of small blue flowers dancing in the fields in the most unexpected places as people have re-discovered a passion for flax. Thousands of hectares of new ground is being cultivated in the great linen belt that runs across northern France, Belgium and into The Netherlands. But it’s the little plots that lift your heart. There’s even one at the Palace of Versailles just outside Paris, although it’s hard to know what Marie Antoinette would have made of that. There is linen sprouting in England and Scotland too and yes, it is being grown in Ireland again as well. In a country where the words Irish and Linen were once inseparable.

Fiona McKelvie: As I go around the Province now giving talks about the history of linen and the future of linen, I know full well that if most people in Northern Ireland were to scratch their skin, they’ve got flax flowing through their veins. Because at one point between the wars, the First and Second World War, there were 50% of the population of Northern Ireland were directly or indirectly involved in the Irish linen industry. And that’s remarkable, when you think about it.

JA: That’s Fiona McKelvie, who like many people in Northern Ireland has long roots in the linen industry and now researches its history and trades in antique and vintage Irish linens. Welcome back to Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews, a handweaver interested in the stories textiles tell us, and the often hidden hands that fashion fibre and cloth into something useful and beautiful. These tales cast a fresh light on our communities, and usually have something new to tell us about ourselves as well.

This episode celebrates Irish linen– both its past and its future, which is not something most people thought it had until a few years ago. Here’s Helen Keys, who once again is growing flax in Ireland.

Helen Keys: And I think that’s where the future of linen production and textile production should lie. That it’s not some huge mill somewhere that everything goes to, that it’s lots of little small operations done at a very, very localized level. I think that’s much more sustainable in all kinds of ways. It’s not one person making all the profit, it’s lots of people getting paid fairly for producing a really sustainable textile, it just ticks so many boxes. And when we first started this, you know, it was just kind of a fun, let’s make some linen kind of thing. But as we’ve gone on, we’ve just sort of realized there’s just so many benefits to this kind of system. There are so many benefits for farming, there’s benefits for textiles, there’s benefits for, you know, reducing carbon footprint that it just, it just makes so much sense.

JA: The story of Irish linen is extraordinary: one of success built on adversity, yes, but also the skills and hard work of the people here in Ireland who created something that was without question the best in the world. Here’s Fiona

Fiona: There’s one amazing statistic that goes back to the late 1800s. In 1892, there were 12 million miles of linen yarn being spun in Belfast Mills every week. I mean, that’s very hard to get your head around.

JA: Those were the days when Belfast was known as Linenopolis:

Fiona: Some of it would’ve gone to be woven into cloth. Some of it was going into making netting for the fishing industry. It was going to book binding to shoemakers. And what’s quite interesting is the likes of Barbour Thread Company based at Hilden Mill in Lisburn. They were one of the leading thread making companies here. There were also one or two others, in and around Banbridge. But about nine companies, got together and formed the, the Linen Thread Company, the biggest thread producing company in the world. It’s Latin name is linum usitatissimum, linen most useful. And that’s actually at the core of this, linen in the past has been used for suture thread. It’s used for kitchen towels. Florence Nightingale nurses wore linen aprons., it’s naturally anti-microbial. It’s cool. It cools you down in a hot climate. It keeps you warm in a cooler climate. if you’ve never slept in linen sheets, I heartily recommend it.

JA: And of course, the Belfast linen mills were turning out complex and densely woven damask tablecloths and napkins that dressed respectable tables around the world from royalty to restaurants – and when the Titanic went down it took with it a quantity of the finest Irish linen ever made. But, it didn’t start like that, Ireland and linen have a long history. Ancient records say that St Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, who died in 461AD, was buried in a linen shroud, But the growth of the world beating linen industry, that sprung up not far from where he died, has its origins in the late 1600s in the ever-prickly relationship between England and Ireland.

Ciaran Toal: And it comes down to the question of wool. You might be wondering, what does wool have to do with linen? Because there was a, a huge industry in Ireland of wool yarn that would be produced and were going into an English market, and English weren’t happy with it. So you actually have a pamphlet war between lots of Bristol merchants Irish merchants, Irish constitutionalists, people who, who use this as an argument that Ireland should have its own parliament. It should be independent. And what happens essentially is there’s a tariff brought in and they try and prevent Irish wool yarn coming on to an English market.

JA: Ciaran Toal is the Keeper of Collections at the Irish Linen Centre in Lisburn. He says that as the English started to protect their own wool and exclude Irish wool, the landowners in Ireland backed the local linen industry.

Ciaran: So like, we don’t want the Irish wool so let’s encourage linen and block their export of Irish wool. And this all happens around the end of the 17th century. And you start to see then from almost a zero base to the end of the 17th century, we have 500, 600 active looms in the north of Ireland producing linen for domestic and, and export. And then we start to see the rise of the, what we’d recognize as the Irish linen industry at the start of the 18th century onwards.

JA: An important part of that rise is the arrival of the Huguenot families fleeing persecution in France. Many of them were skilled weavers and makers who understood the linen trade. Along with Quakers from Britain, they played a big role in establishing the Irish linen industry. At this time almost every community across Northern and Eastern Europe was growing and processing linen and hemp in some form or another. Look at the maps and you will see different names for hemp holes, bleaching greens, retting dams and more scattered across the land. And like everywhere else Ireland grew flax and processed the fibre, but this wasn’t what it became famous for:

Ciaran: The Irish were quite good at producing flax, but they were never the best at producing flax. They were the best at producing linen. But yes, people are growing flax on farms. And actually, you see in the 18th century, and particularly towards the end of the 18th century, there’s encouragement to grow flax from particularly the Linen Board, which is set up around the early 18th century as overseers in, in Dublin to promote and push this new industry. They have overseers who are producing texts on how to grow linen or how to process it eventually how to bleach it. But you have other factors too. You have the rise of landowners particularly where we are here in South Antrim, but also elsewhere around the north of Ireland. Landowners who have these large estates, and they’re given impetus to those on the land to produce flax or to spin yarn or eventually to weave. So if you grew X amount of flax, I think it’s maybe five acres of flax, you were given a spinning wheel. But if you grew more than that, I guess double or triple that, you’re actually given a loom.

JA: But what the Irish did become the best at was processing linen, they worked out how to improve bleaching so it could be done all the year round. The quality was assured and overseen, export markets developed, even though in the 1700s this was still very much a cottage industry

Ciaran: So in the 18th century, the industry was very much a domestic setting. You would’ve had, spinners who would’ve worked at home. The whole family might have been involved in that, because it would have taken several spinners to support a weaver. And then next door to the spinners, you would’ve had the weaver who would’ve been working likely on a, well, definitely on a plain loom in the 18th century. Perhaps in different places they might have a draw loom. So it was very much a domestic setting. And I think people look at the domestic setting and they think, oh, it was hours of toil. But actually, you know, these are independent weavers and spinners who are working on their own terms to an extent. They’re producing yarn, selling it at market, or they’re producing cloth and selling at market. So, they’re able to choose when they work, they’re able to choose who they sell that cloth to. So, they’re really independent weavers who value their position as independent weavers.

JA But gradually that began to ebb away, firstly the putting out system came in – manufacturers would hand out work to individual weavers and spinners, demanding that it be done to time and for the least possible wages. And then in 1824 the death knell of the cottage system sounded as James Kay of Preston developed a method of wet spinning linen on a machine by passing it through a warm water bath.

Ciaran: Almost overnight it kills off the domestic Irish spinning industry because they cannot compete with what’s been produced in a factory. Now, they can’t produce yarn for the higher ends of the industry. So for damask, with any really fine yarns, I mean, that can’t really happen. But more or less it wipes out the domestic spinning industry and it undermines these independent manufacturers. so that this whole domestic scene that you see, it starts to become a thing of the past. And if you want to be a spinner, then you have to be prepared for much lower depressed wages.

JA: And in the 1840s the Irish Famine also drove the mechanisation of linen production.

Ciaran: A really important moment in the history of linen is the Irish famine of the mid 1840s, because you start to see that the cost of labour wages go up, because There’s less people, so many people have left. So before where you would’ve had machine spun yarn, it would’ve went to hand weavers to produce cloth, suddenly that labour force isn’t here anymore, or their wages are too high. And then you start to see the increase of power looms. So, I think they went from maybe a couple of hundred power looms around the 1850s to, by the end of the century, I mean like 300,000. It’s, it’s a huge boom.

JA: The American Civil War gave it further impetus as people couldn’t get cotton easily, but linen was available and the city drew people in from all over Ireland and further afield. Here’s Fiona McKelvie:

Fiona: In Belfast in 1808, the population was 25,000. By 1841 it’s 70,000, but by 1911 it’s 385,000 people. It was the fastest growing city in Victorian Britain, Great Britain. And it was as a result of that, not only the linen industry, but also shipbuilding and rope making that it was eventually granted city status by Queen Victoria.

JA: Most of the workers in the linen mills and factories were women and children, and life was incredibly tough, but Fiona believes we can’t judge those times by our own standards.

Fiona: But generally, the women were, they were glad to have jobs. They’d made that huge move coming from everything they knew in the country up to the cities to live in some fairly straightened circumstances of houses packed together. But they were working, they were bringing home a wage. They were supporting their families. Yes, there were children working as well. About 70% of the workforce in the mills were women and children known as half timers. So, from the age of 14, you could work full time, but before that you would work maybe half a day. But also, mill owners weren’t all you know, the ogres that they’re sometimes painted, and actually quite a number of the mill owners provided schooling, and this is schooling that those children might not otherwise have had. So I think they, they get a bit of a hard rap. In, in my book, I think it’s very hard looking at it from the position of 2024 to look back even to 1924 and judge because they were happy in their work. There were wonderful songs that they would sing to one another and poems just to keep themselves, to keep themselves buoyed up during the working day with wet spinning.

JA: The wet spinning brought its own particular health hazards:

Fiona: Flax is a very brittle fibre, and it needs to be kept humid, otherwise it’s going to break. And as the thread breaks, that’s downtime on the machines and time is money, et cetera. So the floors of the factories would be spread with water. And whilst those working in the cotton industry in Manchester would’ve worn clogs here, the girls chose to work barefoot. Shoe leather was expensive. It would rot if they were standing in water all day. But sadly, with that came all manner of nasty complaints akin to trench foot, I suppose you might say, by standing in, in water. And they would walk home barefoot very often, it was tough times, but they were a jolly bunch. It’s what I’ve been told by people who, you know, who had factories here. They said generally there was a huge camaraderie between the workers. So yes, tough, but I, by the same token, they were putting food on the table.

JA Linen boomed right into the 20th century. In the First World War almost all the new aircraft that took to the skies were covered in fine Irish linen – leading General Sir John French to say that “the war had been won on Ulster Linen Wings”. But as our lives changed, linen began to die.

Fiona: The subsidies that had been given by the government to farmers to produce flax in Northern Ireland were removed, and the way we were living was changing. People didn’t have staff any longer. You weren’t having formal dining any longer on a damask tablecloth every day that was dying away. The whole way we were living our lives was moving away from that rather formal existence of the double damask napkin and the tablecloth. So that inevitably took its toll. And by the late 1990s and early 2000’s, the last spinning mills were closing down.

JA: And after the Second World War man-made fibres arrived which didn’t need to be ironed and looked after in quite the same way as linen. Today in Ireland there are just the remnants of a once proud industry.

Fiona: So sadly, spinning has gone completely, I’m not sure we’ll ever get it back on an industrial scale. But as far as fabric production goes, there are still producers who are continuing here. And the main damask weaver, the only one left is Ferguson’s of Banbridge. And they are still producing damask cloth working far faster than the hand weavers of, of the past. But that is still available. William Clarks of Upperlands who’ve always been experts in finishing cloth: they run the last commercial beetling mill. So that’s still in operation, and there are one or two other small pockets.

JA: And William Clark’s beetling mill is a wonderful survivor. Beetled linen is an extraordinary thing, very thin, and with an incredible lustre – much coveted by tailors and dressmakers. Clarke’s current engines are around 200 years old. They are machines of wood and metal that look like something out of a medieval painting. Duncan Neil is the Creative Director of William Clarks:

Duncan Neil: You’ve just walked in to get the, the cascade of noise. I mean, essentially beetling is a process that’s been used for probably about 300 years in its current form, or nearing 300 years. And essentially, it’s a process that hammers fabric, pounds it over a period of time. The thing with beetling, or the aesthetic thing with beetling, is that it develops a really high sheen on fabric. So that’s why it’s, it’s becoming increasingly desirable, because the lustre is really difficult to replicate with modern machinery. It’s really beautiful.

JA But the real reason these magnificent beetling machines are still in use is that beetled linen is incredibly thin and strong and valued by tailors and couture houses.

Duncan: And it’s a construction fabric, so it’s a fabric that’s never normally seen. It’s usually used in thin strips for seam reinforcement. And essentially the start of the process is taking fabric impregnated for the traditional product with starch, just the potato starch, and it’s put onto the beams wet, and then the hammers are dropped on it for round about four weeks. So to try and describe the engines, I mean, essentially there’s two, there’s two main cylindrical beams on the engines. There’s one on the bottom which is a perfectly round cylinder that’s made out of Beechwood, and that’s where the fabric is loaded onto. Then up above that, there’s a really beautiful spiral helix beam, which is called the wiper beam. And especially it’s like spokes and they lift and drop hammers onto the fabric on the beam below. So, I mean, during the course of the four weeks it takes to produce this fabric, the wet fabric slowly dries out. The fabric continues to soak up the, the solution it was placed in, in this case starch. So, the fibres swells slightly and between the, the swelling and the drying out, what you end up with is a much flatter fabric than you put in. So, it’s a much sleeker glossier surface.

JA: Thanks to Duncan Neil and William Clark and Sons we are giving away some small pieces of this beautiful beetled linen to Friends of Haptic & Hue with the next Travels with Textiles podcast. Duncan says it’s hard not to fall in love with the old beetling engines.

Duncan: I think that’s the one thing whenever we have visitors coming to see the factory, whether it’s existing customers, potential new customers this is the one thing you can always bring people to that. I don’t think I’ve ever had anyone here that said, oh, I’ve seen this before. Nobody’s seen it before. Yeah. And it’s fascinating. Yeah, it’s just, it is a real privilege to kinda be involved with the machines, to be honest and get to learn more about them.

JA: William Clark and Son’s old beetling machines have seen a good deal in their time – the spectacular rise and subsequent fall of a great industry, but they will last a little longer yet, and they are witnessing a new kind of linen industry rise again in Ireland, but this time a very different kind of enterprise.

Helen: The countryside would’ve been covered in flax during the summer. And it’s, it’s really mad when you think about it now that I had never seen a crop of flax. And I grew up in the countryside here. So it certainly wasn’t around being grown on a farm, I don’t think, during my lifetime. So we just had this moment where, you know, we thought, well, why would we not have a go at doing this? You know, we knew that flax had been grown on our farm here before, and we knew that it had been a very successful crop and a very profitable crop. So it just seemed an obvious thing to us.

JA: Helen Keys and her partner Charlie Mallon started growing flax on their small farm not far from Moneymore seven years ago. They are hugely determined people – but this hasn’t been easy. They assumed that if they grew the flax then because this was Ireland they could just send it away to be processed.

Helen: And that is where, you know, we were so naive about that, had we known what we were getting ourselves into, I’m really not sure we would’ve done it. But we just had this really naive assumption that, you know, once we grew the flax, there would be somewhere to send it, to get it processed. And that that was just wrong. <Laugh>. that somewhere, you know, down the road there would be, a scutch mill and, a spinners and a weavers. And we would just send it off to, to be processed. And we’d planned this great range of tableware, <laugh>. And I was, it was gonna be gorgeous.

JA: But the fact was that the entire complex chain of flax production in Ireland had been lost, there was no-one left to ripple, rett, scutch or hackle their fibre, let alone spin it, so being the people they are, they set about putting it all back themselves, and this being Northern Ireland, old linen processing machinery lies about in forgotten corners. So now Helen and Charlie sow their flax on the farm in late spring, and after a 100 days, they harvest it by hand, calling on the community to help them pull the long flax stalks. It’s then dried out and goes into an upcycled cheese vat to be retted, a process which incidentally stinks. It gets dried out again and is prepared to meet Charlie’s recreated masterpiece: the scutching turbine, which strips off the unwanted cellulose of the flax stalk leaving the soften linen fibres.

Helen:. And it was my dad who discovered the scutching turbine, which was in another man’s shed in honestly, in small little bits underneath a pile of other machinery, I would not have known what it was, I wouldn’t have had a clue. But my dad knew this guy who had sort of rescued it from the, the mill and he had stored it there for a good few years. And he and Charlie came up with this mad plan to, to get the scutching turbine. And I have to, I have to confess, I was a little bit dubious that we might be taking on a little bit too much. I mean it was just such a huge project where, you know, even just the process of getting it out of that shed, getting it uncovered, there was low loaders and lots of lifting gear. There was a huge operation to get it all transported over here to the farm. They set it up into the field and I remember seeing it going up there and thinking, when will it ever come out of that field again? That is such a thing for us to try and rebuild that. But really, Charlie has the heart of a lion and he knocked down a building, put the scutching turbine in, then built another building around that sort of rebuild everything around that. And I, I don’t know anybody else who could have done that. It was incredible.

JA: The revived scutching machine saves Charlie and Helen hours and hours of what would once have been back breaking handwork. Helen explains how the flax fibre is prepared.

Helen: So you just rub it back and forth between your fingers and you can see the chaff is coming off. So that’s the outer core, and the inner bit is coming off, and that’s just leaving you with the raw fibre. So if that comes apart really easily, you know, it’s retted and you know it’s ready to go through the machine.

Jo: And then what’s the next step?

Helen: Well, the next step is through the scutching turbine. So we, we can talk you through the sort of stages. It goes through this first, there’s two sets of breakers. So it goes through this first set of breakers and that breaks one side of the plant, gets carried through on the belt. That next little machine just straightens it all out again. Then it goes through a second set of breakers, which breaks the, the bottom half of the plant. So by the time it goes into the next bit, which is the turbines, it will have been crunched up and broken and ready to get the, the chaff brushed off it. So the next stage is the two turbines. And within those, there’s, I believe they’re called swingles, which is a great word, and the swingles spin round. And they brush all of the chaff off the fibre, and that reveals your real like golden hair-like fibre coming out the far end of the machine.

Jo: Then at the far end, you’ve got your fibre

Helen: You’ve got your fibre. It’ll be something like this, which is there might still be little bits of chaff in it. It needs combing out at that stage. And, the next stage would be to go through a process called hackling. And hackling is basically combing it through, through first quite broad combs, getting narrower and narrower. So at the minute we’re having to do that by hand. So that’s a long, long process. But it comes out as beautiful sort of golden hair at that stage. But the next project will be to restore the, the little mini hackler so that we can do that by machine and that will allow us to increase our, our production level again.

JA: But even just with the fibre in this state Helen and Charlie have found people who want to buy that incredibly rare thing, flax grown in Ireland.

Helen: Well, interestingly, we found a bit of a market for just that raw fibre which is amazing now because we can actually sell something, which is great. So 5, 5, 6 years on, we actually have a, a product now, which is great because we’ve spent a huge amount of time and money and energy to get to this point. Hand spinners will buy it and, and use it for processing. We have people who have bought it to make like fake fur. We have people who have bought it to make a sporran, which is amazing. We have people who have bought it for, for use in films and things as set dressing and, and that kind of thing. So there, there’s really interesting kind of market just for the raw fibre.

JA: But to close the circle completely and to be able to grow, process, spin and weave linen once again in Ireland there is still one piece of the puzzle missing, the ability to spin linen thread. On the east coast of Ireland close to the Mountains of Mourne there is someone who can’t do it yet, but is working his way towards it:

Mario Sierra: Over in that corner, there’s a huge motor that should be on top of that machine. We’ve bought a new motor, which is much smaller, but to get the new motor to power the machine, we have a big leather belt that we need to adapt a pulley wheel to go on the motor. It’s, there’s just so many things you need to adapt to, to get old technology and new technology to, to meet in the middle. But as far as the machine itself goes, it’s a, it’s a mechanical machine. There’s no computers to crash, which is great.

JA: That’s Mario Sierra of Mourne Textiles which is are artisan weavers. Mario has located a small wet spinning machine that is around seventy years old and he is busy restoring it in the hope that eventually it will be able to spin some of Helen and Charlie’s fibre. Mario says that not all the knowledge of spinning has been lost in Ireland.

Mario: There are people who still use these machines or members of their family who have spun on these machines. So, yeah, they can remember things. They can remember when, with every machine there’s always like little foibles that they can remember things, okay, well, that, that would always go wrong. So they do this and that. Those are the bits of gold that we need to learn, we need to retain. So the amount of time it takes to learn that, they’ve spent years of being an apprentice to, to get that knowledge. And it’s just, it can go in a generation.

JA: Mario thinks that he can get the machine up and running in the next year and maybe even quicker than that, and like everyone else he looking forward to being able to hold onto some linen grown processed, spun and woven in Ireland again.

Mario: To be honest. I’d look forward to just seeing a cone of the yard <laugh>, that would be success. But yeah, obviously to see something woven in it or, or see a, a garment made out of it would be amazing. I think it’s sort of a, it’s baby steps. It’s small steps. So at the minute we’re doing a very small scale, very just showing that you can make a fibre, you can make a yarn from a plant and, and sort of try and encourage designers to really design and want, trying to create the demand. Basically. If we can create the demand for it, then, then they’ll encourage other people to do it. And it’s sort of a bit like that. And also to encourage governments to encourage local councils you know, local tourist boards, whatever, to take an interest in this in this manufacturing.

JA: It will be an extraordinary moment when Helen, Charlie and Mario succeed in growing, processing and spinning genuinely Irish linen But the modern flax renaissance isn’t just about textiles, people are looking at far wider uses for this versatile plant: here’s Fiona:

Fiona: 10% of current flax production is now being used to produce composite materials. What is a composite material? Think of fiberglass. That’s a composite material, but the energy required to produce a flax composite is considerably less. Flax composite panels are being used to create door panels on the insides of race cars. There’s a company in Perth, in Scotland who are making skis from flax composites. Flax has always had amazing insulation properties and as well as making panels for inside concert halls, for example, to absorb sound or buffer sound. If you think of that in a ski or in a tennis racket frame, the shock to the athlete’s limb is being absorbed before it gets to the limb. So the skis can absorb more of the impact. There are surfboards, there are scooters, I believe the French are even trying to make a wine bottle. So the possibilities are endless. So I think if we think of Irish linen, we can’t just think of it in a traditional way any longer. You may still occasionally use your lovely damask napkin that your grandmother gave you, but the chances are in days not so far away, it may be in the inside panel of your car door will be made of a flax composite. So Irish linen will continue to exist, but in slightly different guise.

JA: Ciaran Tole at the Linen Museum in Lisburn believes Ireland is lucky to have that global brand recognition and hopes in future more will be made of it.

Ciaran: You know, when you think Apple, you think California, you know, when you think linen, you think Irish linen. I’ve actually seen linen produced in Belgium, but marketed as Irish linen because they, it has that association with the, the premium, you know, the zenith part of the industry. And I think we’re very, very lucky to have that. And maybe we’re starting to see locally retailers or manufacturers recognizing that, and that’s how they’re, they’re pitching, they’re not trying to, you know, they’re not trying to beat their competitors on price, but they’re, they’re trading up the fact that they have this linen heritage or, you know, or, or that artisan craft element to it. You know? And I, I think it’s a real advantage, you know I mean, speaking personally, if, if you, if you go into Belfast, you see a lot about Titanic, but it wasn’t Titanicopolis, it was Linenopolis. Where’s, where’s the support for the rich linen heritage, you know? Which really helped build parts of Belfast and support of the industry. I mean, it’s, it’s an industry perhaps we should be really proud of, you know?

JA: And now it has a future as well as past, with a new generation of much more mindful consumers searching for fabrics that have been locally and ethically produced, look beautiful and biodegrade easily. Helen and Charlie certainly think that in the years to come linen’s bright blue flower will be seen once again across many more fields in Ireland.

Helen: I hope so. I, I, I hope, you know, <laugh>, I’d be really disappointed if in the next five years we’re still the only ones growing flax. I really would like to see that there’s more and more people getting involved in it. More and more people growing flax and hemp and miscanthus and other alternative crops. Because We have to sort of get to a point where we’re replacing a lot of the plastic materials and other things with much more natural fibres. And this does it. Absolutely, this does it. I I mean, I just think there’s so many different avenues that you can go with this sort of natural fibrer. It’s really good as part of a, an overall agricultural system, it’s really beneficial for biodiversity. You see the crop in the middle of summer is absolutely, buzzing with bees and butterflies and all kinds of insects. So it’s good for the farm, I think. And it’s it works really well as part of that rotation. And I think there’s just so many applications for those natural fibres.

JA: Thank you to everyone who took part in this podcast, without their deep knowledge, determination, and skill – there would no story of Irish linen to tell, and certainly no hope for it as a modern fibre in a different world. You can find out more about this episode, and see pictures of the beetling mill and Helen and Charlie’s linen fields at www.hapticandhue.com/listen-series-6. Haptic & Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and edited and produced by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production entirely supported by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you something extra every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted by Bill Taylor and me, where we cover a whole range of different textile stories and news. The next Friends podcast will come from a very special exhibition on Scottish Embroidery. And we will be back next month with a new podcast which looks at a textile that had a huge impact on history but is rarely ever mentioned – ships sails. Join us then, but until then thank you for listening and enjoy your making.