Fabric and Foundlings

Episode #29

This episode of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles looks at the system where mothers leaving babies at the London Foundling Hospital often left small textile tokens with them. It gave both of them anonymity but meant that the mother could identify her child in the future.

The dress of the elite tends to be preserved, but we know very little about the garments of the poor, did they dress in hand-me-downs or homespun, or did they have access to anything fashionable? Two hundred and fifty years after these tokens were first left in desperate circumstances we can see them both as a way to tell us about the lives of women in the past and a way to understand what they wore and how they dressed their babies.

The people you hear in this episode are:

John Styles: Professor Emeritus in History, University of Hertfordshire and Honorary Research Fellow at the Victoria and Albert Museum. His book about the Textile Tokens of the Foundling Hospital is called Threads of Feeling and it was written to accompany an exhibition of the same name at the Foundling Museum in 2010. It is still in print and can be bought at https://artuk.org/shop/gifts/books-stationery/product/threads-of-feeling-the-london-foundling-hospitals-textile-tokens-1740-1770.html

His longer book The Dress of the People is in the Haptic & Hue UK bookshop but does not seem to have made it across the Atlantic, but you may be able to find it at a good local bookseller.

Caroline de Stefani is the Conservation Studio Manager at the London Metropolitan Archives. The Archives themselves are an incredible place to disappear down any number of rabbit holes about the history of London and the people who lived in it going back over a thousand years. You can find out more on their website. And if you find yourself in London you can arrange to visit and see documents of interest. It is not possible to see the billet books at the Archives, but you can see two or three of them on display at The Foundling Museum.

The Foundling Museum is one of London’s great secrets and always worth a visit if you have a spare hour or two, www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk

If you would like a lighter read on the subject of Foundlings then I recommend Stacey Hall’s book, The Foundling which was published recently: it is in both the Haptic & Hue UK bookshop and published as The Lost Orphan in the US bookshop

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

John Styles

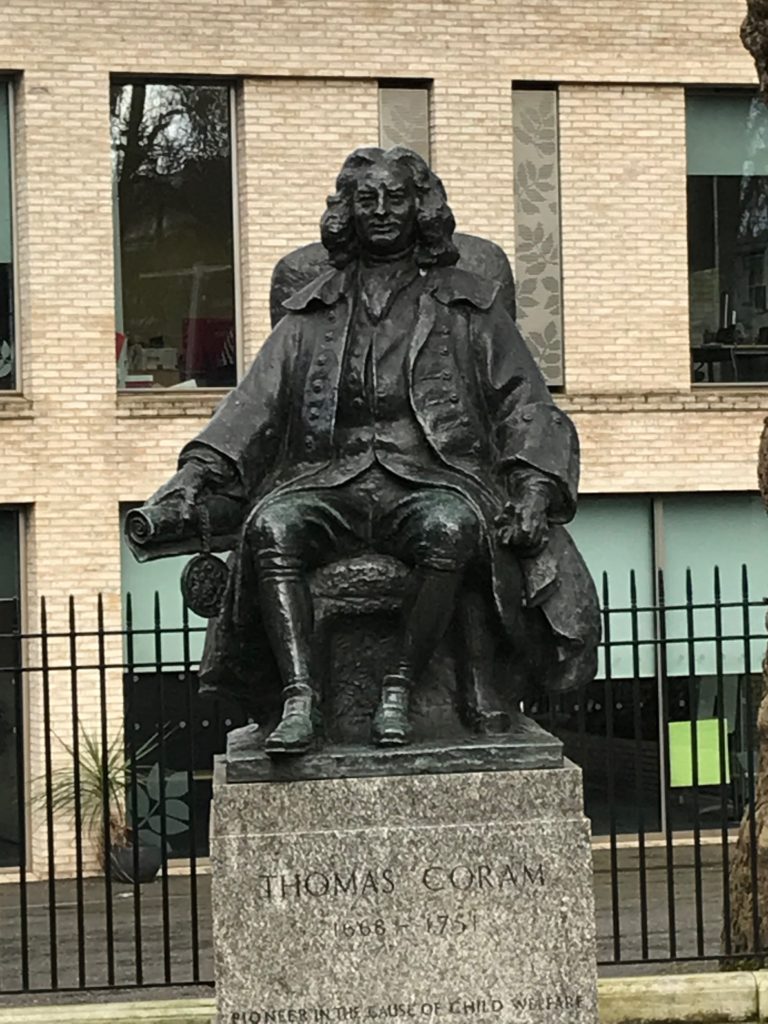

Statue of Thomas Coram

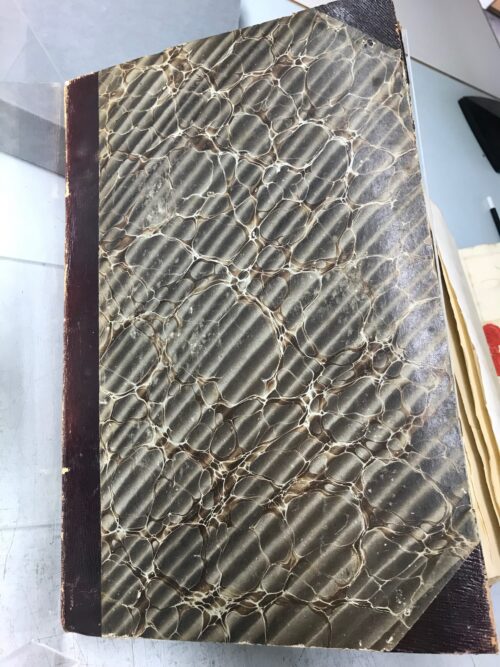

A Billet Book

Caroline de Stefani

Conservation Studio, London Metropolitan Archives

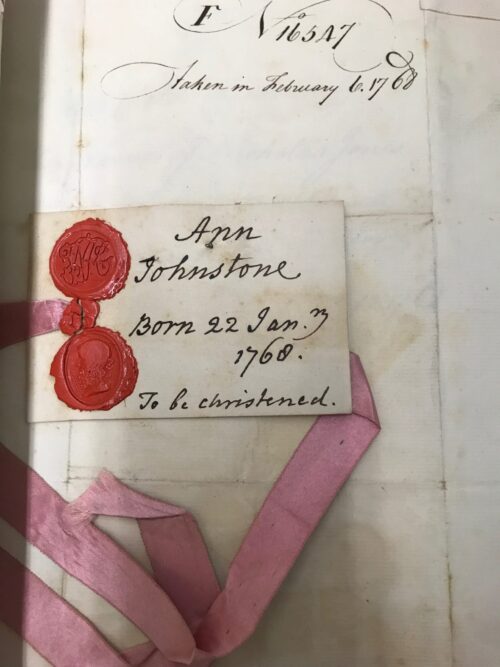

Billet for Ann Johnstone

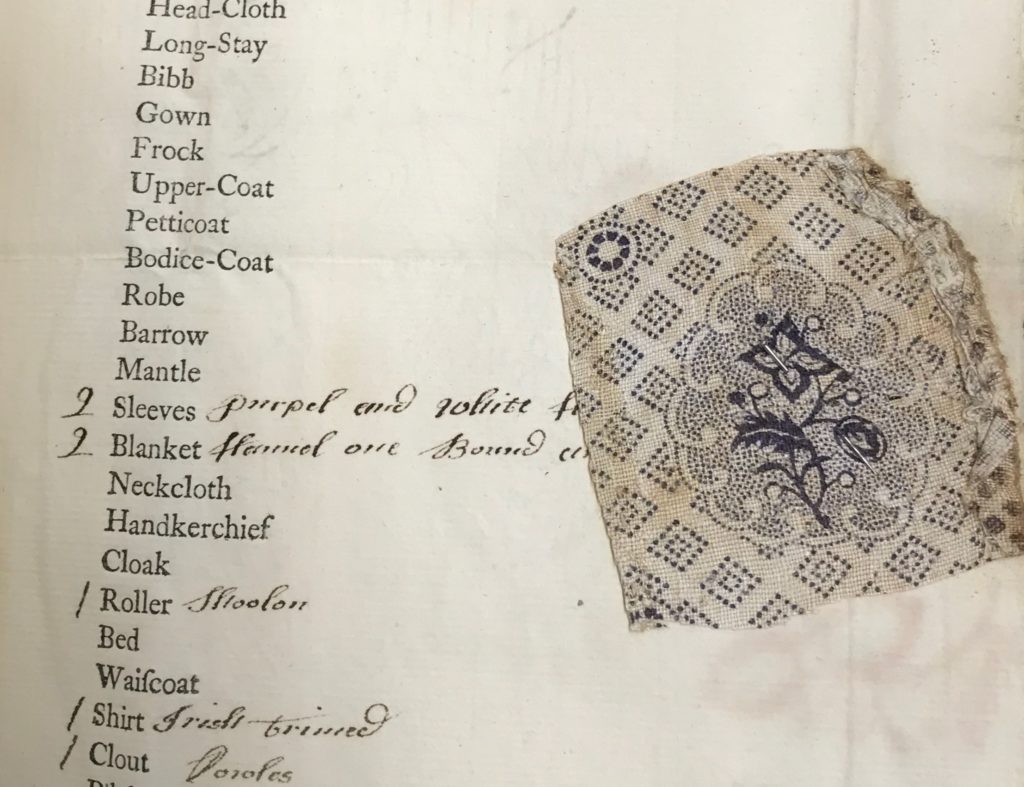

Token for a Foundling

Token for a Foundling

Coram’s Foundling Hospital

Token for a Foundling

Token for a Foundling

Billet Book Page Being Restored

Fabric and Foundlings

Transcript

We begin this time with a sea captain and a voyage to discover how one of London’s darkest problems – the abandonment of newborn babies on the streets – was tackled. His efforts to solve this problem led to something completely surprising – the creation of one of the world’s largest collections of everyday fabrics worn by ordinary women and their babies in the 1700s.

And even though this is history and those described here have long since passed from the stage, it’s a story that has a capacity to move us profoundly and to raise strong emotions – something you might like to be aware of especially if, like Pippi Longstocking, Harry Potter, Snow White, James Bond, Huckleberry Finn or Scarlett O’Hara, you too were a foundling, fostered or adopted.

Welcome to Haptic and Hue – and Season 4 of Tales of Textiles, called Threads of Survival. My name is Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver interested in what cloth in all its forms tells us about ourselves as human beings. Textiles have an incredible power to talk to us if we can hear them: they comfort and console us, create memories, and define who we are – and nowhere more than in this episode in which the secret of your true origins hung on a scrap of cloth.

London in the mid-1700s was a successful and rich city. But not all its citizens shared in that wealth. Grinding poverty, sickness, and violence stalked many of its inhabitants, especially women and children. And this, above all, is a story of these working-class women and their babies, it is also a tale of how textiles gather meaning as time passes, what begins life as something quite mundane, down the years can acquire layers of significance and be transformed into something powerful and extraordinary.

But we start with our sea captain, who returned to London from North America and was appalled:

John: Well, the key to the Founding Hospital being established is a man called Thomas Coram who was a ship’s master, a merchant, a shipbuilder, English, but he worked in the early 18th century in Massachusetts for many years. And when he came back to London in the 1720s, he was horrified to see children abandoned in the streets. And he was determined to set up an institution to house them, but it took him a long time. It took him the best part of 20 years.

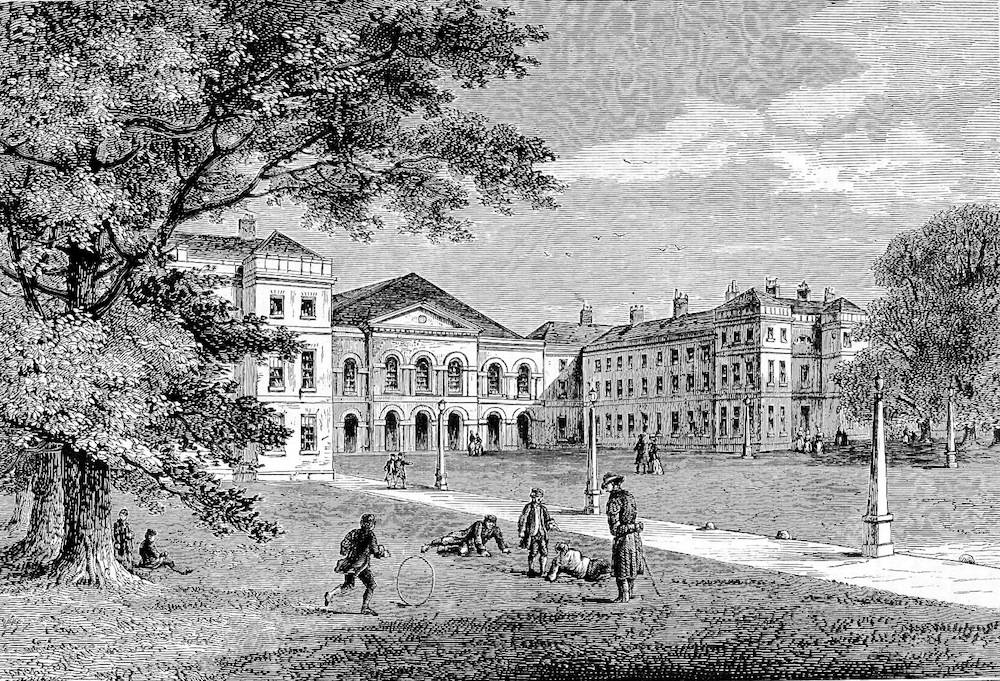

That’s John Styles, Emeritus Professor of History and a specialist in the textiles of this period. Thomas Coram was a man on a mission who simply wouldn’t take no for an answer. He assembled something many of us might recognise today, a committee of the great and good, or at least their wives, and painstakingly, bit by bit, he raised the private money he needed to build his Hospital – London‘s first orphanage – which opened its doors in 1739. In this London was way behind other European cities where convents and nuns had long taken in orphans. But Coram convinced artists like Hogarth to exhibit his paintings for the hospital and eminent composers like Handel to create music to raise money for his project.

Coram’s Foundling Hospital was a grand establishment in what were then open fields on the outskirts of the city. Immediately it had a number of problems: how to select the limited number of children it could afford to take, how to keep raising the money to support them and how to guarantee anonymity to the mothers so that they could bring their babies to the hospital without being identified.

John: The whole system was anonymous. They were very, very worried that if the mother’s name was known, this would be a source of shame because often some but not all of the children were illegitimate. And that abandoning a child was regarded as shameful. So that mothers might and especially mothers who are rejected, might feel so ashamed that they killed themselves, killed the baby, very bad consequences would stem from that. And this, in fact was not just the policy in London. It was the policy of all these founding hospitals across continental Europe as well. They all worked on this anonymous system.

And so the Foundling Hospital had to find an anonymous way of registering each baby, but one that allowed them to be certain which child was which.

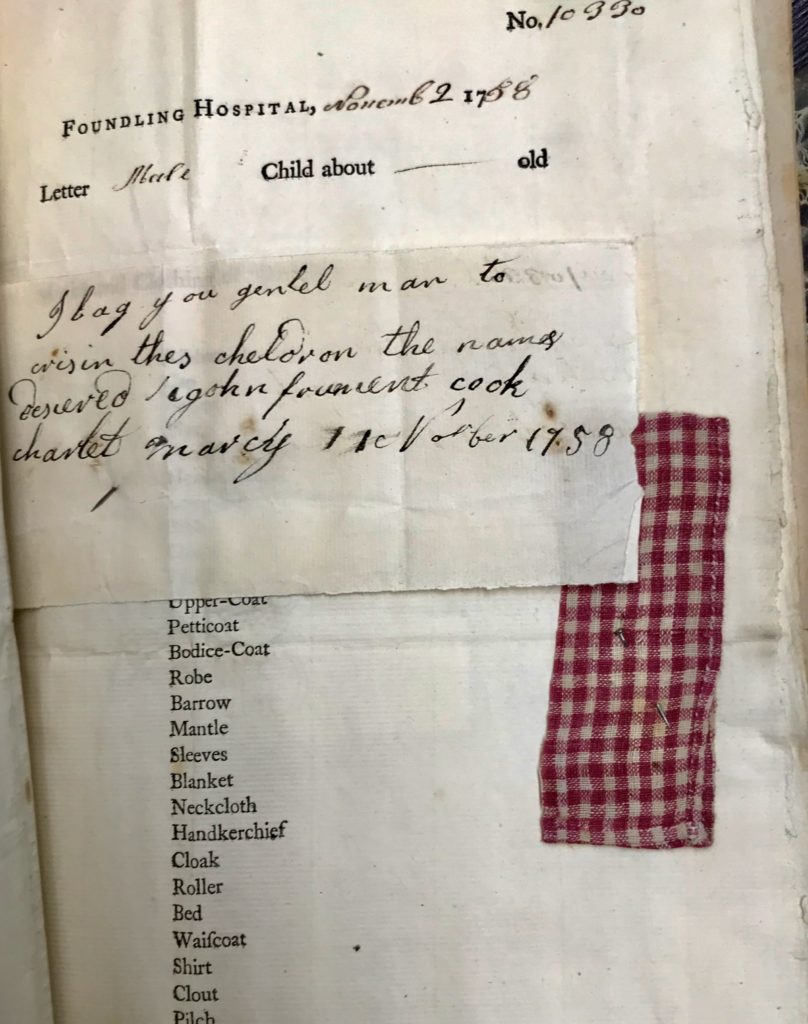

John: Because the other rule, which all these hospitals across various parts of Europe followed, was the idea that if the mother’s circumstances changed, she could take the child back. I mean, there’s a very, very strong belief in 18th century, European culture, Christian European culture, both Protestant and Catholic, that maternalism, that children should be looked after by their mothers. And so that in all these hospitals was a high priority. So you’ve got an anonymous handing over of the child at the start of the process. But you also have a belief that the mother should be able to reclaim the child. If her circumstances change, how can those be reconciled? How do you know whether the mother who reclaims the child is the mother of the child being reclaimed? And that’s where the so-called billet system came in, what the billet was essentially is a registration document for each child.

And although the billet didn’t contain the mother’s name it recorded a lot of useful information:

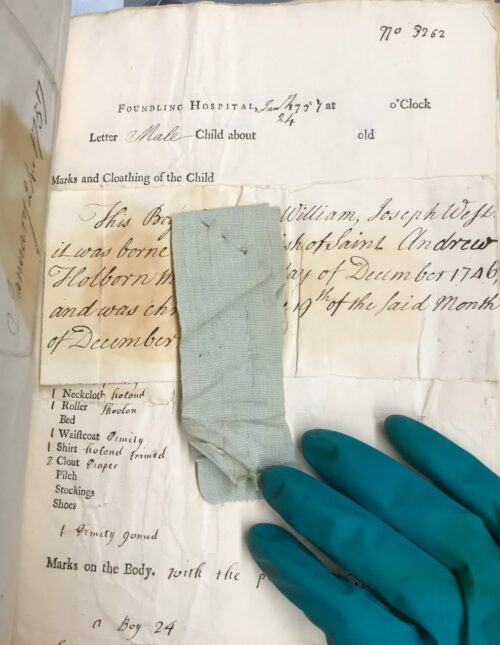

John: It had all sorts of details about the child registered on it in particular how old it was when brought in and its sex. Obviously, it had lots of details about the child’s clothing when it came into the hospital, although the hospital re-clothed all the babies as they were brought in. And remember, we’re talking very often about tiny, tiny babies, one day, two days three-day-old babies. So, they had a list of all the baby’s clothing that it was wearing. And then they had any details of any particular features of the, of the child whether they had a, a mole here on their face or some other characteristic. So that gave a basic document, which identified what the child was like when it came in. And that’s what this billet system was set up for.

The Foundling Hospital also encouraged each mother to bring in a token to attach to the billet – something only she knew about and that she could describe, or produce the other half of if she came back to collect her child. It is hard for us to stand in the shoes of these women in the past who faced this choice – not all of these children were illegitimate by any means – many of them had two married parents, but parents who just couldn’t feed them or afford to keep them. What would you have chosen as your token as you handed over a child that you couldn’t keep, a baby that was probably just a few days old? Most of the women would have been illiterate, to bring a letter might have been difficult, so they often brought what they had to hand, which were the textiles they used every day: snippets from their dresses, a length of coloured ribbon, a fragment of a bright, printed scarf or a little silk cockade or rosette.

John: For a token, you needed a textile that was going to be retrospectively recognizable that a mother five years, six years later, was going to be able to come back and say, this is my textile. Of course, textiles had one other advantage in this respect, which is that you could, unlike a letter. You could cut them in half. So, you could take a length of ribbon and cut it in half, and you’d leave one half, maybe a foot, you know, or six inches of ribbon with the hospital who then pinned it to the billet, to the registration document. And you would take away the other half, which you could then keep as your evidence that you had left that child on that date with the hospital. So textiles had an advantage over, over letters and text and paper. And, and actually, I think interestingly very often in the 18th century, that was a very widely held view. Paper is, you know, easily lost, easily burned, easily wetted, you know, 18th-century homes weren’t exactly weather fast, a lot of the time. So paper is vulnerable in a way, textiles were not vulnerable. Textiles will survive a lot of bending, folding, ripping, you know, experiences that paper would, would suffer with. And so I think textiles to do it with textiles made a lot of sense for both the hospital and the women concerned.

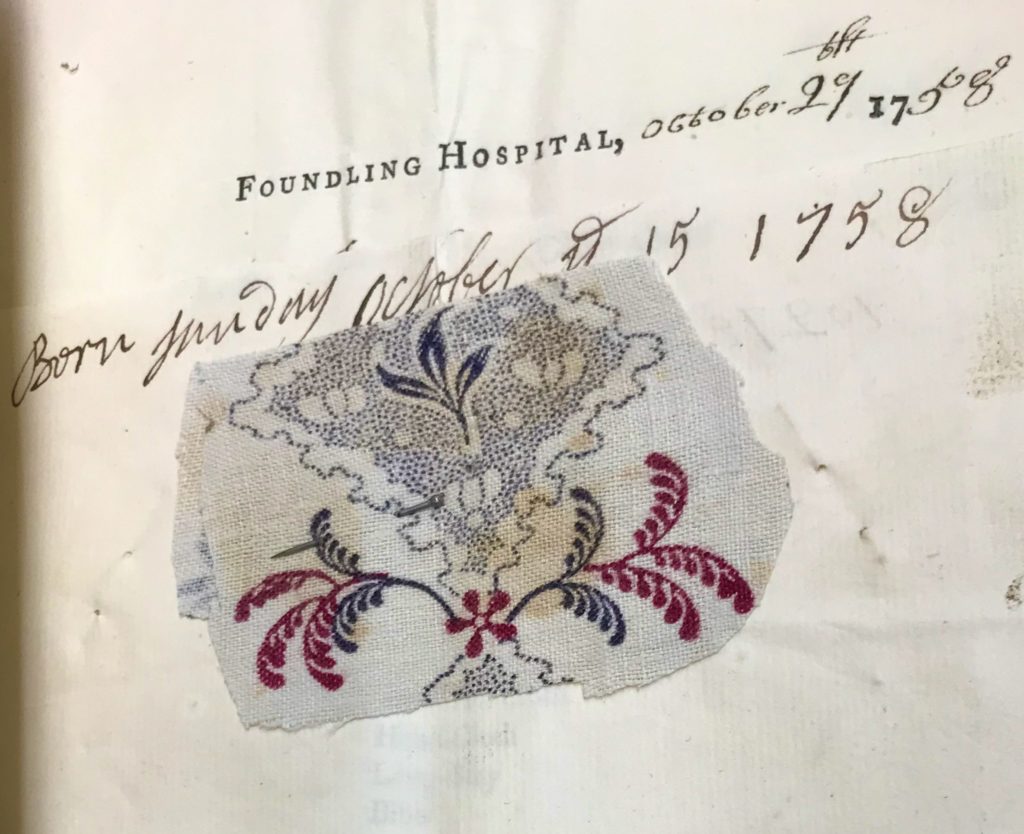

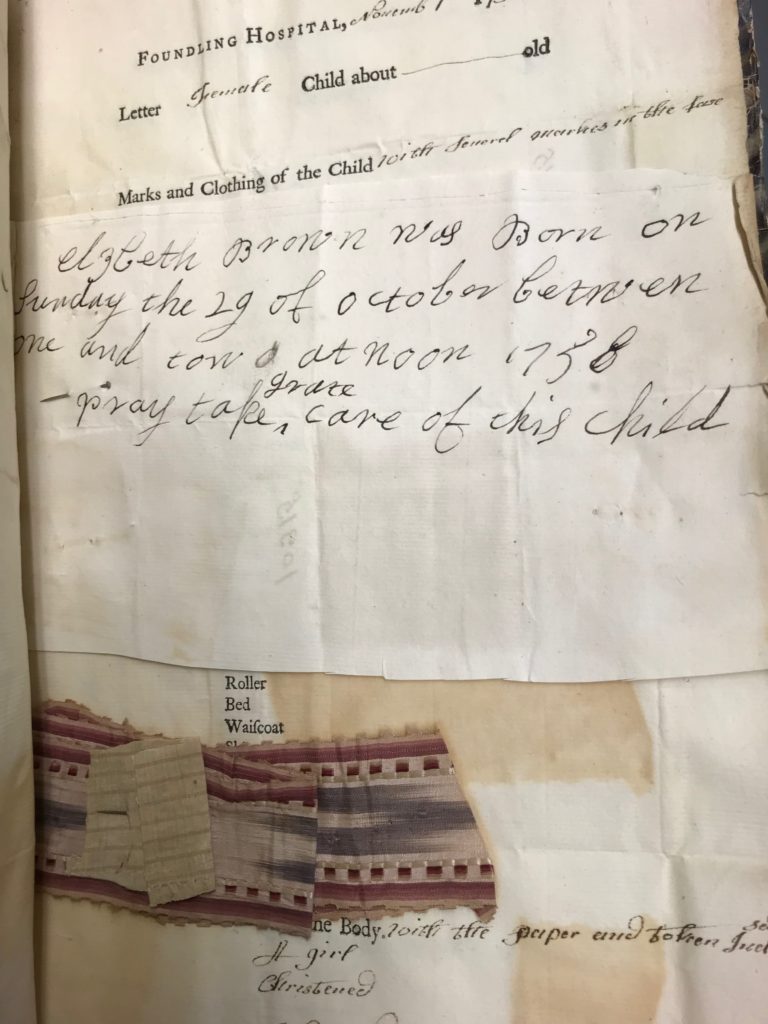

These billets were all collected and carefully kept and later in Victorian times they were bound into books – called the billet books. Each page in these volumes represents an extraordinary time in the life of the child and its mother, the moment at which they were separated, and the textiles, that are still pinned to the pages over 250 years later, are all that connect them together. The little pieces of fabric are the last gift each mother gave her child, and also a record of the parting between the two. I find the pages emotional reading – although we cannot know the circumstances in which each child was given up. Here are some entries:

Foundling Hospital June 30th, 1753: number 1109: A male child about a fortnight old. And with him as his token a tiny handwoven baby’s cap in linen, fringed with lace.

Foundling Hospital November 1st, 1758: Female Child, christened, with several marks in the face. And a handwritten note attached that reads “Elzbeth Brown was born on Sunday 29th of October between one and two in the afternoon 1758, Pray take grate care of this child”. And below it is pinned a beautiful silk ribbon with a deep plum centre and pink squares down the side.

Foundling Hospital December 6th, 1759: Number 14695 A male child about 14 days old. Who came with part of a colourful embroidered sampler as his token.

And finally, there is the baby girl whose token was a cut-out red woollen heart, pinned to a small piece of her linen baby cap and a ribbon of blue silk underneath.

John: The typical token that was left with the babies was a piece of textile if it was not a letter. So the physical token is a piece of textile and three types of textiles stand out. First is ribbons, which tended to be colourful, but cheap. You could buy a length of ribbon, a yard of ribbon for two pennies, three pennies, they were silk, cheap waste silk very often, nevertheless silk, and silk dyes well. So they were very brightly coloured. The second group was check fabrics, which were very widely worn among working women at the time, especially, for aprons, for neckcloths, and so on. So, they were used for accessorizing in one way or another, and of course, checks were made in mainly blue and white, which was the fashion at the time. But, they came in many different sizes of checks, combinations of lines, and so on. So presumably these people could recognize them retrospectively. And then the third group is printed fabrics, and these have been printed principally either on linen or on linen-cotton fabrics. In other words, fabrics with a linen warp and a cotton weft. And, these were the product of the print works around London, which were using the technology of colourfast printing, which had been introduced from India in the late 17th or the early 18th century. It was pretty new technology for Britain and Europe that they were using.

Looking through the billet books and the tokens – one of the things that astonishes me is that these fabrics come from a time before mechanised spinning and weaving. Every square inch of fabric in the billet books was hand spun, hand-dyed, and handwoven. Each one would have taken a great deal of time to wrest from raw material to finished garment. This was a process that many people were involved in and it gave them an understanding and knowledge that we have lost. We have evidence of this because for a short time Parliament, worried about a lack of manpower during a new war with France, ordered the Foundling Hospital to take every child that arrived at its gates, and underwrote the cost. The result was that briefly thousands of children were admitted – over four years they took in 15,000 children.

John: So, you know, the staff were overwhelmed. So what did they do? Well, my guess is that there was a clerk because he wrote out the form and the baby would be held by the nurse, by the female nurse who would be calling out the textiles items of which the clothing was made. And you can see these lists and they say, you know, that this is made from linen. This is made from cotton. I’ve got one here, which goes, you know, the cap, this is from 1759, right in the middle of the war. And it says the cap is made from Holland, which is a kind of linen with a cambric border, a very fancy, expensive, fine linen, a forehead cloth, which is lawn, another fine linen. The gown is sprigged linen, and in this case, red sprigged linen, a blanket, which was a yard of blanketing, a so-called roller – which was something the baby was rolled up in – is a lace cloth. She has a calico waistcoat, a linen shirt, and a piece of rug, what we in England called a nappy, and what in America is called a diaper. And what’s clear is these nurses really know their textiles because I’ve done an analysis of all the printed fabrics for certain years to look at whether the staff of the hospital got the difference between a print on a linen fabric, all linen and a print on a cotton linen fabric, a mixture of cotton linen, 95% of the time they get it right. And, I can only get it right by using a microscope, but they didn’t have a microscope. So they were good. They really knew their textiles. They had a kind of what I’ve called a material literacy, which we don’t really have in the same way now.

John says that some of the most moving tokens are those where the mother has customised part of printed pattern.

John: So what mothers would do sometimes, especially mothers who had a very powerful investment in their children’s future, they cut out one of these little elements in the design, which held some sort of symbolic significance. So you find little bits of fabric with a bud cut out, a bud design cut out, or a butterfly design cut out or, or an acorn for growth and flourishing. You know, these are designs, which symbolize something for them up and that’s what they used as a token.

Children who were admitted to the Foundling Hospital had their billet written out, they were re-clothed and as soon as that had happened they were shipped out to the countryside to wet nurses who were specifically employed by the hospital for that purpose. The other thing that happened was that each child was given a new identity, a new name but one of the interesting things about the billet books is that in a number of entries the mothers try to insist that the child keeps its birth name.

John: It must have been a risky thing to do for a mother because you imagine you’re in a terrible situation, your are destitute, you want your child to be taken in. You know, the policy of the hospital is to rename the baby. The hospital doesn’t want your name. And yet you do have a this bond with the child and you are saying, my child is called. And so, you get these ribbons and these pieces of textile with embroidery, all with these statements. I think that is very powerful. I mean, we know from modern welfare institutions and from a, and from the history of welfare institutions the people who receive welfare are not powerless. They get very quickly to know the system. And that’s one of the reasons why the people who run these systems often fret so much about malingering and exploitation and dishonesty, you know, often unjustifiably, but it does mean that you can’t always believe from when you see a piece of textile on one of these registration documents, these billets, that looks like a, a bird flying free or an acorn that will grow, whether it’s is that what the mother really thought? I mean, she’s dumping her baby on an institution, you know, or was it what they thought the hospital would want, that the hospital would look more favourably on them and their baby if they performed or presented themselves as, you know, deeply concerned with the baby’s welfare, that that’s what the hospital would expect, and that would encourage them to take the baby. So there’s always this sense: was the hospital being played? I mean, I think very, pretty rarely actually, but that was, that’s always a concern. If you are looking at these things and trying to interpret them when we know nothing about the actual mother herself or anything it’s hard. But when the mother, you know, gives a ribbon with her name on, when she knows that’s exactly what the hospital doesn’t want, you have this sense, this mother really, you know, has something, has a bond with this baby that she may be giving it up, but it, you know, it’s, that’s still the bond. And that must have been a heart-wrenching decision for the mother.

The Foundling Hospital did its best by these children – but in the 1750s half of all babies in Britain died in their first year of life. On top of that, the babies that came to the Foundling Hospital were from deeply disadvantaged backgrounds, two-thirds of them died, which is hard for us to comprehend. But there are some bright stories in there, some of the children – just a handful of the thousands that were handed over – were reclaimed. There is a beautiful patchwork needlecase made of many highly coloured woven and printed fabrics. It was the token given in with Foundling number 16516, a Male admitted on February 11th, 1767. He was given the name Benjamin Twirl by the Hospital. His mother Sarah Bender, who had christened him Charles, reclaimed him when he was 8, in June 1775. These are tremendously compelling stories but over the years both the lives of the mothers and children have disappeared in the candlelight of history, and what we are left with are the Billet books and their fabrics, which give us, nearly 300 years later, a way to peer into the past and to understand a little more about how these women lived their lives.

JA: We are on a Windy Street in London, in front of an anonymous 1930s building, it doesn’t look like much, but it’s one of the city’s great treasure houses, home to over 1000 years of its history, stored in 70 miles of archives.

This is the London Metropolitan Archives – I lived in London for many years and I had no idea it was there – but it’s an incredible place and this is where the Billet Books now live. They still belong to Coram, which today is no longer an orphanage but a charity working for better chances for children. Caroline de Stefani is the Conservation Studio Manager at the Archives and she is responsible for conserving the billet books:

Caroline: They are in various states. I mean, considering that they are textiles and, as you know, textiles are very light-sensitive, and obviously when they have been added to the letter, they were not clean. And at the time the quality of the material was probably not the best. I mean, we’re not talking about velvet or very expensive textiles. So, they already were attached in not in a perfect condition. Unfortunately, obviously, because it’s organic material, they do degrade naturally. And because they also bound in volumes, some textiles, they have been folded several times, they have been pinned with pins and needles on the paper. And that also doesn’t really help the textile and the paper. So, the textile while degrading has also stained the pages, which are now discoloured, and you can see, the shape they have left on the paper. So overall, they’re quite vulnerable and fragile. And this is the reason why usually the billet books, have restricted access because they’re also difficult to handle.

Caroline’s focus is to ensure that the billet books and the textiles, tokens and notes they contain don’t deteriorate any further:

Caroline: They are kept in strong rooms where the temperature is low and the relative humidity is also relatively low, and they are kept in an environment that is stable, which is very important for textile and paper and, and books in general, you sort of delay the natural degradation of organic material and the other way that we, we, we are, we make sure that we minimize the damage is providing good packaging. So, every single book has a bespoke box and the boxes are kept in other boxes that’re made of archival grade materials. So it’s buffered. Another element is providing document handling to staff and readers so that they know how to handle a particular book or document. So you also to minimize the damage because handling, especially items that are complicated, like the billet books, can enhance then if you don’t do it properly, then you can enhance the damage. So by providing also document handling, you can limit the damage. And then obviously we do intervention let’s say proper conservation, which means if there are tears on the pages, if the textile is particularly dirty, we do dry clean it.

At the moment Caroline is preparing 3 billet books for display at the Foundling Museum – which tells the story of the Hospital.

Caroline: So, what we have here, we’ve got three volumes. They have been selected for the next display. That’s, we’ll be open in April and it’s an introductory gallery at the family museum. So, these three billet books they are, as we see them, they’re on book stands because they’re very important that they are supported when they’re open. And what we see here is a random opening of the three books, this one has a pink silk ribbon, I think and it’s the silk ribbon is attached to a piece of paper with two red wax seals. And the ribbon is a little bit crumbly. So, we need to work a little bit on making sure that is secure while it’s on display. We see needles because this textile has been attached to the document with the needle. There are tears along the page. And so, we need to sort that out as well before it goes on display.

Caroline: Let’s see, this is a little bit difficult to identify, Yeah. It’s, it’s quite solid. It’s very dirty here and it’s quite degraded as well. So the pin is rusting and the degradation products from the textile has transferred to the next page. So you see a discolouration on the other side of the page, and this is also a problem that you find quite a lot on this billet of books. The tokens and the textiles they are coming in various colours and patterns, they are printed embroidered. This one it’s folded, unfortunately, is that a leaf printed?

JA: Yes. It’s a beautiful printed leaf with dots in the background.

Caroline: Yeah. So, it’s very fascinating to see all the patterns

John Styles became interested in the Billet books because he was writing about what ordinary people wore in the seventeen hundreds – but it was tough to find information about them:

John: And I was working in a museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, at the time and so I was surrounded by the clothes that had been worn by very rich people in 18th century, England, but none of the clothes worn by poor people survived. I mean they do survive, but they survive in the British Library because all the linens were converted into paper because paper was then all made from linen rags. but that wasn’t a help to me.

But the billet books were a goldmine for him – the only large collection of clothing samples worn by poor people that survives from that period. It pointed him to a number of interesting things. The first was that most babies in poor families wore garments cut down from women’s clothing – there were very few purpose-made baby clothes. The second was more surprising, it was that even very poor women in this era could follow fashion.

John: It alerted me to the fact that these women were able to have these very fashionable garments or very fashionable fabrics in their cheaper varieties, coarser and less colours. I mean, the cost of a printed cotton or linen turned basically on two things, first of all, how fine the fabric was, its fabric, weight. And secondly, on how many colours you had, the price went up for each colour you added. So, a two colour was a lot cheaper than a five-colour and indeed in the commercial correspondence, that’s how they described it, a five colour, so and so, a six colour so and so. So, these women, and as we know, that the designs of these fabrics often followed the broad trend of fashion in fine silks, I mean the fine silks worn by Duchess and the ladies and, you know, the royal court set the fashion. And that was true all over Europe. I mean, and principally the silks of Lyon, but Spitalfields was a near competitor, those set the fashion, but you could reproduce at least some of the look of those silks with print blocks very much more cheaply on cotton and linen.

And if you want to know more about silk making in Spitalfields and Lyon there are Haptic and Hue podcasts on both – these were both of course centres of production for the elite and what we have in the billet books is very much the fabric of the poor. But they tell us that by the mid-1700s cheap printed cottons were being turned out in large amounts and in patterns that could be quickly updated – according to fashion, and it was being produced much closer to home than previously thought.

John: This demonstrated to me that by the 1750s, very poor women could have access to these printed fabrics, but they, but it also alerted me to the fact that they were not getting that access with imports from India. The calico craze of the 17th century is often said to have transformed what women wore in Europe, not true, what they’re doing, what they’re wearing are fabrics that use the Indian technique of fast colour printing, but it’s fast colour printing that’s done on European fabrics in the area around London, by print works in London, which have if you like hijacked the technique, they’ve learnt the technique.

So the key elements of a system of fashion for all women – whatever their status – seems to have come into being much earlier than we thought.

John: There isn’t a kind of class split between the clothes that poor people wear and the clothes that rich people wear, essentially the look, the basic look of women’s clothing is what they all wear, you know, some sort of combination of a gown and the petticoat, and that’s true of very poor women, and it’s true of very rich women. Now, the poor may strip the gown off and just work in their shift and petticoat when they’re washing or whatever, but still, they all virtually all have gowns. And they often have a work-a-day gown, which is, and that’s why by the later 18th century, you get the idea of the so-called stuff gown, the cheap worsted gown is the typical working woman’s workwear. Then for the weekends, for Sundays and for holidays, high days and holy days, as they say, these women will have something that’s much more fashionable and coloured. And very often it’s one of these printed fabrics. So the Founding Hospital collection of tokens actually tells us a lot about women’s fashion and especially about the trickle-down character of poor women’s fashionability in the mid 18th century.

The billet books have lots of tales to tell us – but at the end of the day it’s the mothers and their babies that draws Caroline de Stefani

Caroline: It’s really moving. And yeah, I, you didn’t think that someone would put all these efforts to make sure that some children would survive? We have to see the positive, many children, they were not claimed back, but they, they at least had a future, some of them.

And for John Styles – the historian – it’s the sheer diversity of what the billet books can show us that fascinates him:

John: They have many, many different meanings they’re relevant to many, many different debates and issues. And that’s the joy of them. But on the other hand, one can easily kind of slightly forget their original purpose, but sooner or later, you always come back to this sense, to that, that very visceral physical realization that these things represent a child, a child who, given two-thirds of them died very quickly, probably died. And that child also that was separated from its mother. And that there’s the tragedy of that comes back. Even, even when you’ve looked at 5,000 of them.

Thank you for listening. If you would like to find out more about the modern-day Foundling Museum where you can see the billet books and find out more about the Hospital, or if you would like to see pictures, links to background reading for this episode or read a transcript of this podcast you will find these resources at www.hapticandhue.com/listen.

Haptic and Hue is an independent production which is supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee. If you would like to contribute you will find the button on our website at www.hapticandhue.com.

Next time we will be travelling to Italy to discover if the astonishingly beautiful textiles depicted in the paintings of the Renaissance can still be made – or if they have disappeared just as surely as the Montacutes and Capulets no longer pursue their deadly feud. Join us on the first Thursday of every month for a new episode of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’ll leave you this time with a short anonymous poem by one of the mothers who left her baby at The Foundling Hospital in 1759.

Hard is my Lot in Deep Distress

To Have No Help where most should find.

Sure nature meant her sacred laws

Should men as strong as women bind.

Regardless he, Unable I,

To keep this image of my heart.

‘Tis Vile to Murder! Hard to Starve,

And death almost to me to part.

If fortune should her favours give

That I in better plight might live

I’d try to have my boy again

And train him up the best of men.