A Sliver of Deep Blue Cloth:

Unravelling the Textiles of Enslavement

Episode #39

This podcast and the text below discuss terms considered offensive and inappropriate today

This episode of Haptic & Hue unravels the story of a tiny piece of cloth that begins on the upland moors of Yorkshire and takes us to America and the Caribbean. The tale also involves Wales, the Lake District, Ireland, Scotland, Germany, Poland, Russia, and the Baltic. The different light that textiles cast on this history show us how profits from the system of slavery were part of the everyday lives of workers and merchants all over Britain and Europe and didn’t just benefit a few rich plantation owners.

Further Information

In this episode, the bills of lading refer to ‘ells’ of fabric. This was an old measure of fabric that came out at just over a metre, or about a yard and a quarter.

University College London’s Centre for the Study of Slavery has a wonderful collection of public resources detailing estates held and compensation paid to individuals as well as other records. You can find it here.

The Bank of England’s inflation calculator is great fun. It will calculate prices in modern equivalents right back to 1209. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator

The People you hear in this episode are:

Sarah Chubb, Archives and Local Studies Manager at Derbyshire Record Office. The online records can all be found and searched at: https://www.derbyshire.gov.uk/leisure/record-office/derbyshire-record-office.aspx The DRO is on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/derbyshirerecordoffice/

Professor Chris Evans can be found on Twitter @cevans3

You can find out more about his work at https://www.southwales.ac.uk/research/research-excellence-framework/ref-2021-impact-case-studies/wales-and-atlantic-slavery-redressing-historical-amnesia/. His book: Slave Wales: The Welsh and Atlantic Slavery: 1660 – 1850 can be found here

Cromford Mills is always worth a visit. You can find out more here. David Smith is a volunteer guide at the Mills and happy to show you around.

From Sheep to Sugar is the Community Project that set out to find out more about cloth making in Wales. So far very little work has been done on cloth making in this context in any other part of the UK.

There are two other books that may be of interest: the first is David Alston’s book: Slaves and Highlanders which is about the ‘silenced’ histories of Scotland and the Caribbean. Then there is a new book coming out in June called Slavery, Capitalism, and the Industrial Revolution, by Maxine Berg and Pat Hudson, in which Welsh Plains, Kendal Cotton, and Penistone cloth feature in a chapter on the industrialisation of the textile industry in Britain.

Box at Derbyshire Record Office

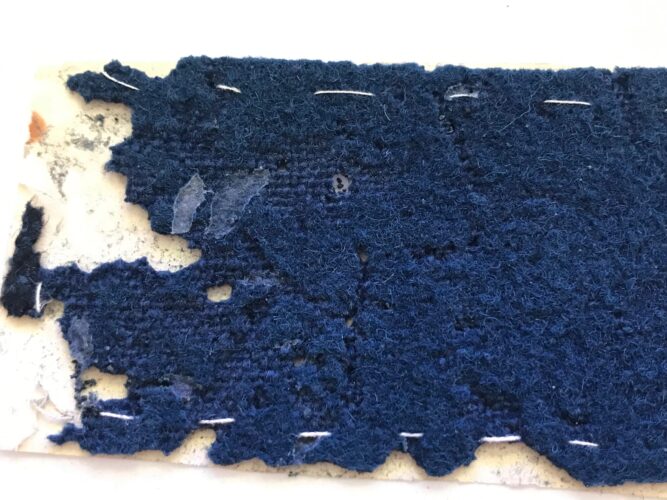

Cloth Sample – courtesy Derbyshire Record Office

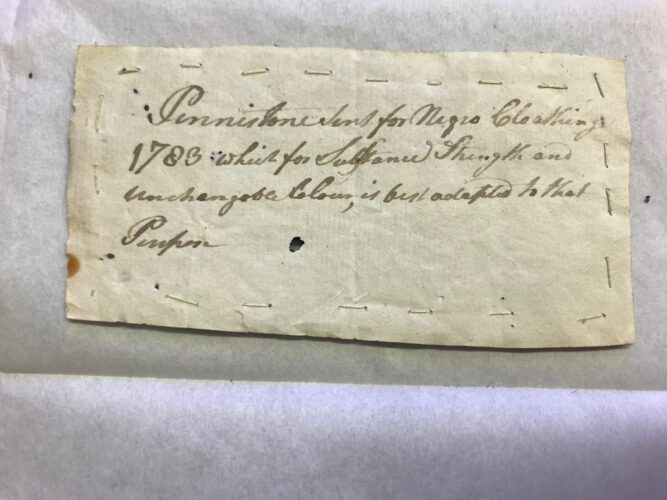

Reverse of Sample, courtesy Derbyshire Record Office

Sarah Chubb, Archives and Local Studie Manager, Derbyshire Record Office

Derwent Valley January 2023

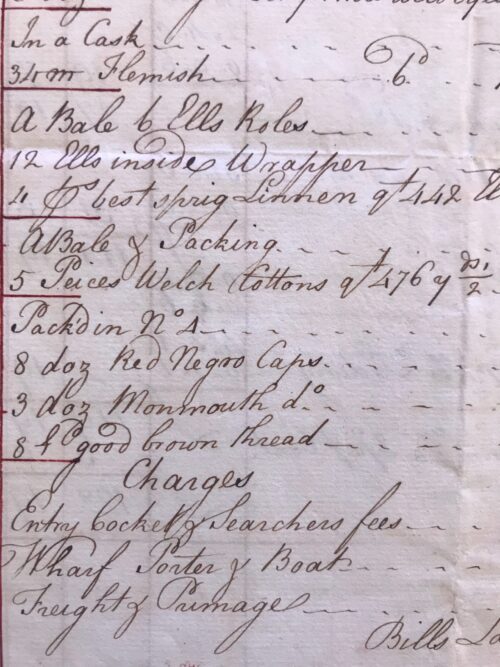

Lading Bill 1752, Courtesy Derbyshire Record Office

Professor Chris Evans

Welsh Fulling Mill – Postcard Collections, National Monuments of Wales

Sugar Cane Workers, Jamaica, copyright unknown, circa 1900.

David Smith

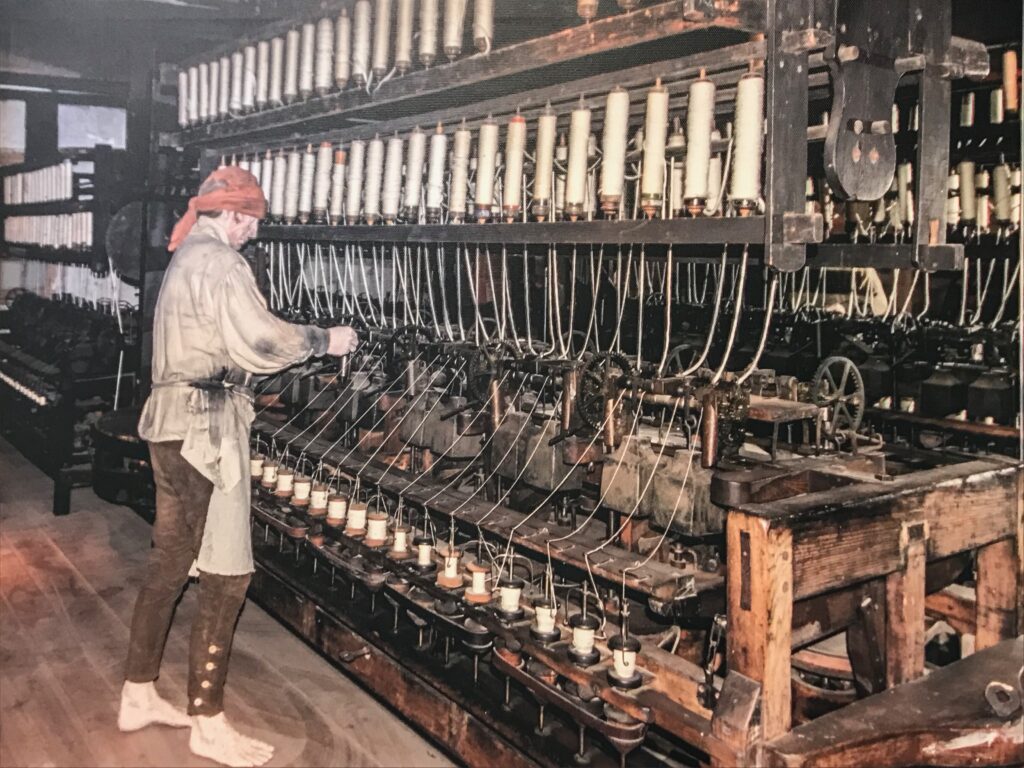

Richard Arkwright’s Spinning Frame, Cromford

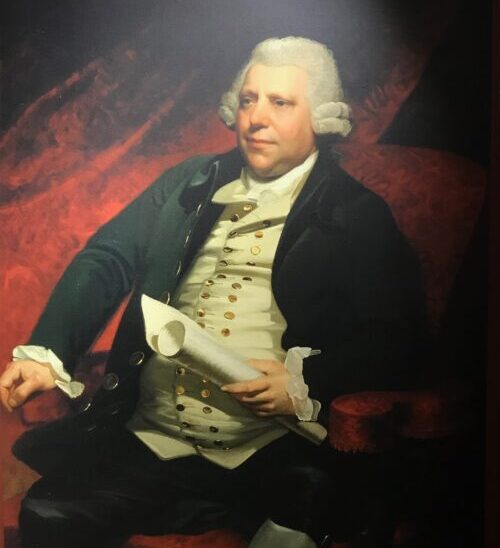

Richard Arkwright

Cromford Mills

The Factory System Arrives

Cromford Mills

Script

A Sliver of Deep Blue Cloth: Unravelling the Textiles of Atlantic Enslavement.

JA: It’s extraordinary that a tiny sample of forgotten cloth can open the door to an unknown world of the past and change how we see history, but it can. One academic has called the small sliver of fabric that is at the centre of this episode ‘as rare as hen’s teeth’. Much more than that it reveals the truth about the textiles of enslavement, and crucially about how the economics of slavery were part of the everyday lives of workers and landowners all over Britain and Europe. It also points the way to the start of the industrial revolution. It is a remarkable survivor, it’s a deep blue colour and slightly moth-eaten, but then it’s nearly 250 years old and for the past 60 years it has lain unnoticed – but not uncared for – in a public record office in England.

Sarah Chubb: It’s a sort of relatively small swatch of an indigo blue fabric quite thick and coarse I suppose. It’s tacked with white thread onto a piece of paper. That’s cut down to about 12 and a half centimetres by six and a half centimetres. So that’s the size of it.

JA: For those who don’t do centimetres, that’s five inches by two and half. And that’s Sarah Chubb – the Archives and Local Studies Manager at Derbyshire Record Office in England. On the back of the piece of paper the sample is tacked to, is some writing:

Sarah: There’s a little note written in 18th-century handwriting saying that it’s “Penistone sent for Negro clothing in 1783, which for substance, strength and unchangeable colour is best adapted to that purpose”.

JA: This is Penistone cloth, which is thick and deeply fulled with a high nap like a kind of baize, and it is currently the only known surviving sample that has been found in Britain of what used to be called ‘slave’ or ‘negro’ cloth. This episode of Tales of Textiles is about this fabric, which was used to clothe millions of enslaved people In America and the Caribbean for nearly two hundred years, and more widely about the textiles of enslavement. I need to say that in doing this we explore some of the records from that time that often use words like those written on this piece of cloth that we consider offensive and inappropriate today. We will look at what archives and records officers are doing to address this, but you need to be aware that this episode tackles the system of enslavement and European and American attitudes to it in the 18th century. In the research on transatlantic slavery, almost no-one seems to have asked about the different light that the fabrics of enslavement can cast on those who were enslaved and the system that treated them so appallingly. That’s partly because so little of this cloth has survived, which is why this tiny sample of cloth matters so much. And the threads that we can pull in this tale are surprising. This is a story that involves Wales, Ireland, Scotland, America, Brazil, the Caribbean, Germany, Poland, the Baltic, and Russia as well, of course as England.

Welcome to Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles, my name is Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver, interested in what cloth tells us about ourselves and our societies. Often the stories and information that textiles can give us are ignored and we lose a whole dimension of human experience. This podcast is about trying to restore that.

But back to Derbyshire, and in particular, Matlock where Bill – Haptic and Hue’s Editor and Producer – and I found ourselves, on a half-dark freezing day in January having made a 200-mile trip from home. We’d made the drive because in the episode about Mount Vernon – number 36 – uploaded in January – I’d talked to Liz Millman of the Welsh Plains Online Research Group. She had told us about the different kinds of cloth that were made in Britain and exported to America to clothe enslaved people – but she told me she’d never seen any of it herself and had never heard of any that had survived. No sooner had the episode gone out than news arrived of a tiny sample of cloth called Penistone Cloth – made in Yorkshire – that was in the Derbyshire Record Office in Matlock. Could we go and see it? As we turned out to be the nearest to Derbyshire, Liz herself being in Australia. Well yes, we could, and we arrived in Matlock, at the wonderful Record Office, to be shown a tiny box containing this rectangle of cloth and a sheaf of original documents relating to a plantation in Barbados. Here’s Sarah:

Sarah: So this piece of cloth is part of the archive of the Fitzherbert family of Tissington Hall in Derbyshire. So they’re one of our local county gentry families, and they’ve been at Tissington Hall since the 11 hundreds, I think, it’s a very long-standing old family. And as tends to happen with these kind of old gentry family collections, it had been deposited at the record office for safekeeping and public access for a number of years. I think it first came in 1963. And then we got bits more, and more and more over the years. And then finally I think the last deposit came in 1992. The collection was owned by the Fitzherberts, but then its ownership was transferred to the public realm basically in lieu of inheritance tax. So, it’s been allocated permanently to the record office.

JA There are public record offices like this all over Britain and they care for and provide free access to lots of detailed information that wouldn’t otherwise survive.

Sarah: The archives of these kind of landed gentry families tend to be very rich in both local history and national and international history because these were people who, for a start, they were able to keep records in the way that ordinary folk weren’t. So, they had in their houses muniment rooms where they would be storing their title deeds that showed the land ownership and all their family correspondence and their estate records. So, the people that they employed, how much money they spent on repairing buildings or on how many pheasants they killed <laugh>, all sorts of things like that. So, it’s this kind of amazing record of, these sort of very privileged people in the county. But within that is also information which can be relevant to anybody. If somebody wants to research the history of their house, for instance, and their house was part of the Tissington estate, then there would be material in the archive that would tell them that. So, you can have people who use it for a very local interest because they’re perhaps researching an ancestor who worked at Tissington Hall, for instance. Or then they have a, a much broader sort of academic interest because these people were often sort of a bit the movers and shakers in society, or they tell us about that their level of society and, and the way people dressed, thought, ate all, all sorts of things.

JA: But inevitably these records skew history because we see events through the eyes of the land and plantation owners, not those who worked for them or were enslaved by them.

Sarah: Oh, yes, yes, very much so. Because the poor people who were working perhaps on the estate or, had some sort of small cottage somewhere they may not have been able to write, they wouldn’t have been able to afford paper, they wouldn’t have been able to afford to keep these records for generations to hand them over. So yes, so history is often written very much from those kinds of collections, and it does give a bit of a skewed record. And, I suppose, the history of enslaved people is the absolute epitome of that because we have records within the Tissington archive of people who were enslaved in Jamaica and the Fitzherbert family owned those plantations. And we can glean tiny amounts of information about those people because we have names, for instance. But an enslaved person would often just have a single name given them to them by the enslaver. Trying to track the history of these people is phenomenally difficult. So, we have vast amounts of information about the people who owned the plantations, but incredibly little about the people who worked on them.

JA: But the records in the Derbyshire Record Office that came with this tiny cloth sample have lots of information about the textiles that were sent regularly to the Turner’s Hall Plantation in Barbados:

London: August 1st 1752: An invoice of sundry goods shipped on Board the Prince of Orange – Captain Stiles for Barbados for the proper account and risk of William Fitzherbert:

Bales of Six Ells Roles

12 Ells Inside Wrappers

Best Sprig Linen Wrapper

A Bale of Packing

5 pieces of Welsh Cottons

8 dozen Red Negro Caps

3 dozen Monmouth Caps

8 dozen good brown thread.

JA: Every year the ships leave for this one plantation in Barbados with around 140 people living there with a great deal of fabric on board:

London 31st December 1784: Invoice of goods shipped on board The Supply. Luke Meriton Commander of Barbados, on account and risk of Sir William Fitzherbert viz:

7 pieces brown Penistone – 410 yards

24 yards best straining cloth

60 pairs of blankets

36 and a half yards of Silesia Lawn

100 yards of Irish Holland

JA: And there is more – Osnaburg Flaxen, Kendall Cotton, yards of plain white cotton, more blankets and lots of thread, but only in brown. These are just the fabric items that we can see recorded in the documents that survive. Of course, alongside those are all the sugar ladles, mule bags, harnesses for horses, muskets, gun and pistol flints, swords, ropes, chains:

Chris Evans: What we need to remember is that the slave economy of the Atlantic is a really critical element of the wider British economy as it starts to industrialize in the 18th century. So, Atlantic slavery has ramifications that are not restricted to a wealthy elite. Its effects ripple out more widely, indeed. Think of it this way, that the Caribbean Sugar Islands in particular are best thought of as being akin to oil rigs. That’s to say they are dedicated production platforms specializing in producing something that is very high value, that’s to say sugar and everything else that’s needed is bought in from outside. That is the workforce, of course, enslaved Africans, but it’s also most of the food that those people eat. And it’s also the clothing. And of course, it’s the industrial plant as well. So, everything is being funnelled into the sugar islands from outside. They’re very artificial environments. And what that means is that the sugar islands support a wide range of support industries that are necessary to keep sugar production, the real profitable part of the operation going.

JA: That’s Professor Chris Evans of the University of South Wales who specialises in the Industrial history and the history of Atlantic slavery in the age of abolition. He says textiles were a significant part of the imports needed:

Chris: These people have to be maintained. They have to be fed, they have to be clothed because they are assets from the point of view of their enslavers. And that meant that they needed, if you like, prison uniform to keep them productive. Because if people were poorly clothed, they didn’t work very well. They suffered greatly in winter, their productivity declined. It’s worth remembering at this point that we’re talking over time in the little ice age. So particularly those people who are enslaved in parts of North America endured very bitter winters indeed. So, clothing was highly necessary. Workwear that would sustain people and that would protect them from the most adverse environmental conditions was something that was very, very important. And that required that two particular types of fabric were imported. One was linen, which most enslaved people wore next to the skin in the form of a, a loose shift perhaps. And the other was wool outerwear, which would protect them against the cold.

JA: So, we have these two kinds of fabric, wool and linen, both hardwearing. These weren’t exclusively made for the plantations but the demand did make a big difference to some very poor areas of the UK:

Chris: In Britain, we know that the wool outerwear was usually made in wet upland parts of Britain that were not good for arable agriculture. And where small rural households needed something to keep them going during sort of slack periods of the agricultural year. So we’re talking about areas like mid-Wales, we’re talking about areas like the Lake District, and we’re talking about moorland Yorkshire, in other words, places where it’s pretty hard to make a living. These are not rich areas. They’re not rich areas now, and they weren’t rich areas then. So, they were therefore full of households, of families who were looking for a kind of industrial by employment, if you like. And that could take the form of spinning or of weaving.

JA: In Britain there were several types of this kind of handspun handwoven woollen cloth all with different names reflecting the area it was made in:

Chris: We know of Welsh Plains. We know of what were called Kendall Cottons, which is a form of woollen made in the Lake District. We know of Penistone, of course, from that huge moorland parish of Penistone in the West Riding of Yorkshire. We know that these are made on a sort of cottage industry basis in rural locations, and we know that they were bought up and funnelled to port cities by local merchants. We know the outlines, but we don’t know a great deal in detail.

JA: Chris and his colleagues are starting work on a project that they hope will fill in some of the gaps. Our tiny sample is Penistone cloth which means that it would likely have been made from local sheep. Penistone had its own breed of sheep adapted to harsh upland conditions. The wool was probably spun and woven in a cottage or farmhouse in West Yorkshire and then finished locally and pinned out on tenterhooks on a drying green before being taken as a bolt of undyed cloth to Penistone Cloth Hall – which still survives today – and sold to a merchant. It is likely at this stage that it was taken to London and dyed deep indigo there. It was then sold to the agents of Sir William Fitzherbert and, like millions of yards of other upland cloth all of it, save for our tiny sample, was then shipped to the Caribbean and America: A long journey for those days:

Chris: Well, I think the little sample of Penistone cloth is very, very important, because it is a reminder that this stuff existed. That it was sufficiently important for a merchant to have a swatch of it. That it was something that was exchanged over long distances. And therefore, that these ostensibly remote rural places that have no connection with the world of Atlantic slavery were in fact far more networked than we imagined. Even today, we think of sort of mid Wales that have been incredibly remote place that has been untouched by the modern world, but that’s really not the case. Mid Wales in the 18th century made cloth for very, very distant places across the Atlantic Ocean.

The other type of material mentioned in the ships’ invoices is Osnaburg. This fabric crops up over and over again in Europe and America. In many senses it is the stuff of history.

Chris: Osnaberg is a very interesting material. The name in English is a corruption of Osnabrück, the Northern German city-state, which was a great centre of linen production in the early modern period. So in the same way, now that we say, right, I’m going to do the hoovering, we don’t mean you’re necessarily going to use an article made by the Hoover Corporation. You are, going to just use a vacuum cleaner that we call a Hoover in the same way. Cheap coarse linens in the 18th century were called Osnabergs or Osnabriggs. They might not even been made in Osnabrück. And as you suggest, many of them were made in Scotland. Many of them were, were made in Ireland. This is quite a widespread activity.

JA: In fact, Osnabergs were pretty much made everywhere: in Germany, America, England, Ireland, and Scotland. So much of this cloth was turned out of the village of Dairsie in the Scottish county of Fife that they renamed the place Osnaburgh. This fabric was ubiquitous in the 18th and 19th centuries – it is the stuff that covered many of the wagons that rolled west across America – sailors’ uniforms were made out of it, sheets, curtains, feed sacks as well as clothing for the enslaved. The flax processing and weaving were done in Britain, Ireland, and Germany. The flax itself was partly locally grown but also came from Poland, the Baltic, and Russia. The market for both Osnaburgs and the Woollens was dramatic:

Chris: The great mystery, of course, is how much went to the Caribbean or to British North America, and how much was used for other purposes. But certainly, we can be sure that absolutely enormous quantities went across the Atlantic because you’ve only got to look at the way in which the market was expanded. Think of it in this way, in 1690, the number of enslaved people in the British Sugar Islands stood at something like 87,000. By 1812, the enslaved population of the British Caribbean was at 743,000. So, if you’re looking, where is the most expansive market available to cloth merchants in the 18th century? It’s going to be found in the Caribbean. And the population for figures for the British colonies on the American mainland tell a similar story. Slavery, there is a little slower to get going, but it very rapidly accelerates in the later 18th century. So, by 1812, you have nearly 1.2 million enslaved individuals in the United States. So, the market is absolutely colossal and it’s come from nothing to enormous over the course of a century.

JA: What we do know from the records is that every enslaved person probably received between four to six yards of cloth every year – that’s around 4-5 metres. And there’s a simple reason none of this survives except a few samples:

Chris: It was used, it was worn out and it was reduced to rags. No one had any interest in keeping it because it was a mark of degradation. And the market for, say, Welsh plains declined very sharply after emancipation in the British Caribbean because people did not want to wear rough Welsh wools. They wanted, where they could, a form of costume in which cotton featured more prominently.

JA: And of course, we have very little in the way of direct evidence that tells us what people thought of the fabrics and clothes they were given under this system;

Chris: Very little that’s direct and certainly not from the 18th century. There’s some evidence from the 19th century in the form of slave narratives from the United States, that’s to say sort of testimony from people who had escaped slavery and were writing autobiographical material where they looked back on their enslaved time of youth for the 18th century. We don’t have a great deal, but we have indirect evidence about how people felt because what they always tried to do was embellish what they were given. The materials we’re speaking of are usually undyed. They’re very coarse. They’re not of sort of superlative quality needless to say they are workwear. But what we invariably find out is enslaved people were never satisfied with the ignoble materials that were given out to them. And they did try to add flourishes of their own, adding ribbons or head scarfs, or any kind of little touch of colour that could individualize what they were wearing and make of it something that was more than what their enslavers intended.

JA: And there again is that wonderful spark of creativity amongst the enslaved that Christine Checinska spoke about in the last episode about carnival and costume. They were makers and creators and they had hard-won, deep textile skills even though there was only brown thread to work with. But what also interests me is did the people who were producing this cloth understand where it was going?

Chris: That, of course, is very difficult to determine because the people we’re speaking of are very, very poor. Some of them would’ve been illiterate in areas like mid-Wales in the 18th century. There really wasn’t any kind of newsprint to speak of. So, you couldn’t buy a newspaper. There wasn’t a great deal of information available to people. So, we really don’t know. They may have done, they may have not. I think the thing to stress here is the vulnerability of these households, these were people who were living on the edge at a time of great economic hardship and who were trying to keep body and soul together. So, from their vantage point, I think they were just producing something that would bring in a few pennies every week that would help survival at a time of great hardship.

JA: There’s another important link in Derbyshire’s story. I’m standing at a World Heritage Site Cromford Mill – not far from Matlock. This complex of old stone buildings was built in 1771 by Richard Arkwright, inventor of the water frame for spinning cotton – Cromford is known as the Mother of the Mills. Cromford is just a few miles from the Derbyshire Record Office. It’s a fascinating place and has a unique position in textile and industrial history. It plays a vital role in this story, but we need to go on an enjoyable detour to get there. Here’s David Smith who is a guide at Cromford.

David Smith: Its claim to fame is, it’s the world’s first successful water-powered spinning mill. Now that’s rather a mouthful. It may sound rather obscure, but what Arkwright did here was to establish the principles of the factory system, the principles of mass production, which went on to change industry in this country and throughout the world. So when he died, people referred to Arkwright as the father of the factory system and Cromford, where we are, as the mother of the mills. So that’s why it’s important.

JA: Richard Arkwright was one of the great figures of the British industrial revolution – a man who made his fortune from cotton spinning.

David Smith: He became the richest commoner in the country. <Laugh>. So he, started off from a very humble background a poor family, a large family. His father was a tailor, mother pretty busy looking after all the children. He didn’t go to school because he had to work, he was just taught basic reading and writing at home. So, for him to become the richest commoner in the country is some achievement. But to top it off, he also became Sir Richard Arkwright. So, a tremendous achievement.

JA: Arkwright was nothing more than a barber by trade, but he proved to be a brilliant businessman. Until the late 1700s, all textile production globally had been more or less in the home. Our swatch of blue cloth was produced in a cottage system. And as Margarita Gleba explained in Episode number 37 – Is The Needle Mightier Than The Sword, that had been the case since time immemorial. Into this picture comes cotton in the mid-1600s, cotton from India, Europe goes mad for it because, unlike flax and wool, it can be easily printed and washed, it’s light and soft, and it looks wonderful. It starts to be imported in its raw form for households to spin.

David Smith: Families produced cloth and women did the spinning and men did the weaving. So, the obvious thing to do was to give the women the raw cotton and say spin that into yarn. They found that very difficult simply because they weren’t used to doing it. They were experts at spinning wool because that’s what their mothers and grandmothers had taught them to do. Spinning the cotton was much more difficult. So, they could do it, but it was slow and the end result was often not very good.

JA: Arkwright teamed up with an inventor called John Kay who had half an idea for a machine that would spin cotton. He had been unable to get it to work and one story even says he’d thrown it in the garden in disgust. Arkwright offers him a wage to work on it in secret until it functions properly. Kay eventually achieves this and as soon as he does, Arkwright seeks backers with capital and gets a patent on the machine.

David Smith: Now this is the basis of his fortune because of course if he can make this machine work on an industrial scale, he’ll make a lot of money and he’s got a monopoly, anybody wants to use it has to pay Richard Arkwright for doing so. But first of all, he’s got to get it to work. Now at this point, he has an important idea because the obvious thing for him to have done was to hire his machine out to people, to women to use at home for spinning, because that’s how industry worked. For some reason, Arkwright said, no, I’m not going to do that. Instead of taking the machines to the people, I’m going to bring the people to the machines. So, he’s going to put all these machines together in one site. He’s going to do that in a mill. And that’s what we’re sitting in at the moment, his first mill. So instead of taking the machines out to the people, he’ll bring the people to the machines and that’s what he progresses to do in Cromford.

JA: And that is how factories and mills were invented, and although it did change the world in the early days it was touch and go:

David Smith: Well, eventually it was very efficient, but moving from his small prototype to a big industrial machine wasn’t easy. So he built this in 1771 and we believe it took him five years to get everything working properly because going from a small machine to a big machine introduces all kinds of new engineering problems. Of course, he can’t buy these anywhere, he’s got to make them here. So it was a real struggle to do that. He’s got to build his mill, he’s got to recruit a workforce here in Cromford. Nobody’s ever done this kind of work before. There are a few mills, the one in Derby predates this but was not a mass-production place. It took him five years during which time we can only imagine. He got a great deal of harassment from his financial backers.

JA: Today the old stone mill buildings are a beautiful place but two hundred and fifty years ago this would have been very different. Arkwright employed largely women and children and it would have been hard and dangerous work with long hours.

David Smith: He was certainly employing over a thousand people at its peak. So, a lot. Not just in this mill. He built other mills here. But, of course, this is only one bit of Arkwright’s empire. He built mills in other places and crucially, anybody who was using his machine was paying him royalties. So, at one point it was estimated there were 140 cotton spinning mills in this country in the late 18th century. And Richard Arkwright had a financial interest in a hundred of them. So, he had a huge empire.

JA: And where was the cotton coming from to keep these increasing vast cotton spinning mills turning?

David Smith: We believe the cotton was not really coming from India, where the finished cotton cloth came from. We believe it was coming from the West Indies and Brazil in the early days. Of course, the United States soon cottoned onto this, sorry, about the phrase, but they started their own cotton industry and, and eventually they became a supplier. So it is coming from the West Indies, it’s coming from Brazil and later it’s coming from United States. Some bits may have come from the Levant. And of course, it’s all produced by slave labour. It’s coming from plantations operated by slaves.

JA: So in Derbyshire – just one county – we have records of the wool and flax that left Britain to clothe the enslaved, who harvested and processed cotton, which was then imported back to Britain to be spun and made into yarns and textiles here. It would be a similar story in Spain, France and the Netherlands. David thinks that, to begin with the mill workers would have had little or no idea about where the raw cotton was coming from:

David Smith: It’s a job. And, of course, for nearly all of them, it’s their first regular paid job prior to doing this. They’ve had, they’re poor people with irregular work. The men are probably doing some framework ting the women, maybe some spinning the children helping at home, maybe a bit of agriculture. But this is their first regular paid job. So yeah, it’s a job with a house.

JA: But by the late 1700s people definitely did know and many of the workers and even the mill owners themselves became wanted to see the abolition of slavery: Here’s Sarah Chubb of the Derbyshire Records Office.

Sarah: There was a nationwide movement for abolition for many years. So in the Derwent Valley for instance, the owners of the cotton mills, many of them were actually pro-abolition, but it’s very difficult for them not to use cotton that was produced by enslaved people because that was, the bulk of the cotton that was out there that was suitable for their purposes. If you want to parallel with the modern day, I think this is very much like us now being very conscious of the climate crisis, but needing to get around in our cars. And I think it was a bit of a similar situation in the late 18th century and early 19th century where people were very aware that this was an evil, but they couldn’t quite work out how to not participate in it. And we do also have within our collection, we have the archive of the Wilmot Hortons, another Derbyshire family, where one of the Wilmot Hortons worked for the government and was very involved in this discussion. And we have his papers, collecting views and the evidence of people about the abolition question as well. So yeah, you see both sides really in the archives.

JA: During Covid lockdown one of the volunteers at the Derbyshire Record Office began tracking the names of all the enslaved mentioned in the Fitzherbert records to try to restore some humanity and individuality to the enslaved.

Sarah: So, we had those all in an, in a big spreadsheet. And what we’ve been trying to do, and this is a very, it’s, it’s difficult <laugh> and we’ve only sort of been partially successful so far, is to try and create a biographical entry for every enslaved person and link that to the documents in which they’re mentioned. What’s very difficult about that is that names are reused and you can’t be sure that the Ben mentioned in one document is the same as the Ben mentioned in another. Sometimes it’s possible and very, very occasionally, the names will say something like Suki’s Thomas, for instance, so that, you know, that Thomas was the child of Suki. So that’s our ultimate aim. It’s, it is a really, really painstaking and long and difficult piece of work. But ultimately that’s what we would like because that would help to redress that balance, between the people who are mostly mentioned in our catalogues, who are the wealthier people, and the people who did the actual work which are the enslaved people and, give them an actual presence.

JA: And what about the language we find in these old records?

Sarah: Well, one thing we don’t do is kind of remove that language if it’s original to the document because it’s important to understand the context of the time, and understand that that language wasn’t considered offensive in the day. So, times change and within our living memories we can think of, I’m sure of changes in vocabulary that have happened. So, these, these are always changing and you, you do want to kind of preserve what was originally said because that is our history. But what we would tend to do now in catalogues is, for instance, put it in quotation marks. So, when it talks about clothing for Negroes, you know, the Negroes is, is a deeply offensive term now. So, we would be putting that in quotation marks to show that that is original language, not our language. And one of the pieces of work that we trying to do as well is look back at actually the archivist’s language in our catalogues as well, because perceptions change, language changes. And we need to also think about how we’ve catalogued who we’ve fore-fronted in our catalogues. We recently noticed in one collection that where there were photographs of family members, the boys are always listed first with their full names and then the girls attached on at the end. and with just their Christian names and that will have been, an unconscious bias on behalf of the archivist <laugh>. So, that’s an ongoing process because we’ve got kind of how many about half a million catalogue records, <laugh>. So, you can imagine it’s an immense job to try and keep those up to date. But the other thing we do, is when we do find something, as in with the FitzHerbert collection and all the material relating to enslaved people, is that we do put a content warning on now to acknowledge that we know that this is offensive and oppressive language. We think that is important.

JA: The slave trade and then the institution of slavery was outlawed in a series of steps across the British empire that were completed in 1838. The slave owners were compensated for the loss of their slaves. Sir Henry Fitzherbert, who owned five plantations in Barbados and Jamaica received nearly £20,000 in compensation, which according to the Bank of England inflation calculator is around £1.7 million pounds in today’s money. It’s a long time ago, but Professor Evans believes that there is still a culture of denial about the prosperity that the system of enslavement brought Britain.

Chris: Oh, completely. I think national amnesia is a great failing of ours. I remember, I think it was in 2015, the then British Prime Minister David Cameron, addressed the Jamaican parliament and said very bluntly, it was time to move on as he put it, from slavery and to stop complaining about it and complaining about the legacies that it had left. Well, that’s very easy to say. But David Cameron has never, to my knowledge, suggested we should move on from World War I and junk Remembrance Day on November the 11th. No one says that in Britain, we will remember them, this is the mantra. But when it comes to slavery and British colonial activity, people are very, very happy to say it’s nothing to do with us. It’s something in the past. And something for which we feel no connection. Whereas if you ask people who won World War ii, they would come back instantly. We did <laugh> even though we weren’t alive. I contributed nothing to victory in World War 2i <laugh>, none, hardly anybody left alive today did. But we won World War 2, and yet we have nothing to do with colonial slavery.

JA: There is a great desire on the part of many of us to say ‘Slavery, oh this wasn’t my family, we weren’t plantation owners, mine were just peasants’– I’ve said it myself. But what the textiles tell us is that it goes much wider than the elite families. Millions of people who lived in Britain, America, Ireland, the Baltic States, Silesia, Spain, France, and The Netherlands profited from the trade in textiles from the poorest to the richest and our entire societies have acquired wealth at lots of different levels from the institution of slavery. And Professor Evans believes we continue to benefit today.

Chris: Oh, I think the legacies are very clear. The riches that were made in the colonial world in the 17th, and 18th into the 19th centuries were colossal. And most of that was transported back to Britain. And there some of it was used for conspicuous consumption by the very rich, but large amounts of it disappeared into the British financial system. It was used for industrial development. It was used for infrastructural development. And the results of that are still around us. We are a rich society in global terms. Yet the places where those original riches were generated remain extremely poor places because the flow of investment was outward. They invested in Britain. We didn’t invest in them. So what you have left in the Caribbean societies where there was no educational system set up, where infrastructure was geared exclusively to the export of sugar and other plantation commodities, and where very little was done to diversify economic development, once the sugar boom had ended, there was nothing left. And the legacies, therefore in the Caribbean, are of sort of intergenerational impoverishment and a very unhealthy system in terms of education and in terms of healthcare.

JA: Thank you for listening to this episode of Haptic and Hue, and I owe a great deal of thanks to the wonderful staff of the Derbyshire Records Office and Sarah Chubb, to Chris Evans for his work in unravelling the mysteries of Welsh Plains, Kendall Cottons and Penistone cloth, and to Dave Smith for his enthusiasm and knowledge of the extraordinary site that is Cromford Mills. If you would like to see pictures of the Mills, the cloth, and some of the documents in the file at the Records Office or read a full script of this podcast, you can find them all on Haptic and Hue’s website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews, and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a member of the new Friends of Haptic & Hue, which costs £50 a year or £5 a month. This keeps the podcast truly independent and free from sponsorship and advertising, and brings you extra content every month. If you’d like to find out more, it’s on the website at www.hapticandhue.com/friends.

Next time we are off to the ballet – a very special ballet where artists and designers working with textiles helped to change the fashion and art of the time.

But this time I would like to leave you with the Christian hymn Amazing Grace. This was written in 1772 by the poet and clergyman, John Newton who had himself been involved in the Atlantic slave trade as a ship’s captain, transporting captives. He wrote the hymn after becoming convinced of the need for abolition and it has been seen through the years as carrying the message of delivering the soul from despair and allowing sinners to repent. It is sung here by the Golden Gospel singers.