A father stands at the top of the stairs, a family is preparing to go out. By the door the mother is putting on the baby’s coat and shoes. The father suddenly yells: ‘Rugga hunt!” and the other three children dive around the house searching for a bedraggled piece of worn out cotton, which might be anywhere. They can’t leave home without it, all know the consequences of trying to do this.

A mother pushes her child along the crowded streets of the city, the child drops off to sleep with the movement and unseen, lets a plastic doll dressed in orange acetate drop from her grasp. The mother and child spend tear-stained hours searching the gutters for this loss, without success.

A family reaches the airport for a much-anticipated holiday, a child panics as he remembers he has failed to bring a small, grubby, square of brushed cotton with him. Dad is despatched home in a taxi to pick it up, missing the flight, at considerable expense.

Alice’s Rugga

Most of us have seen the need for comfort blankets first hand, and if we haven’t, Schulz’s long-running Charlie Brown cartoon with Linus and his blanket as a ubiquitous reminder of the power of textiles to give security and comfort.

Much of the time we take textiles for granted: we wear them, wash-up with them, draw them as curtains at night, sleep in them, warm and dry ourselves, sit on them, and we protect ourselves in different ways with them, from firefighters to surgeons. They are everywhere and not a day goes past when we don’t feel them and the different textures they have, although this haptic sense of touch is usually an unremarked part of our everyday experience.

But for children the need for a particular piece of cloth can be intense, only that one will do and life is all but impossible without it. Alice – for whom Rugga was a vital companion in childhood – is now a mother herself, and Rugga is, these days, a thin piece of tasselled cotton with holes in, but still carries an emotional charge for Alice:

“I still have Rugga – I know exactly where she is although I don’t use her, but is lovely to see her. I found her soothing in the way that someone stroking your hair is, it was so calming to snuggle up with Rugga and get comfortable.” She covered her nose with Rugga and with the same hand sucked her thumb. “It was the soft texture of Rugga that was lovely and also the smell, of a detergent they don’t use now.” Rugga came to school with her: “I remember it wasn’t until I had just turned 10, that I said to my mother, I think I need to stop sucking my thumb and thinking this was a very grown up conversation.”

As she stopped sucking her thumb so the need for Rugga faded. When she was older she would find Rugga in the cupboard and “have a little moment”. She says her husband was introduced early on in their relationship, and he passed the test, which sounds vital!

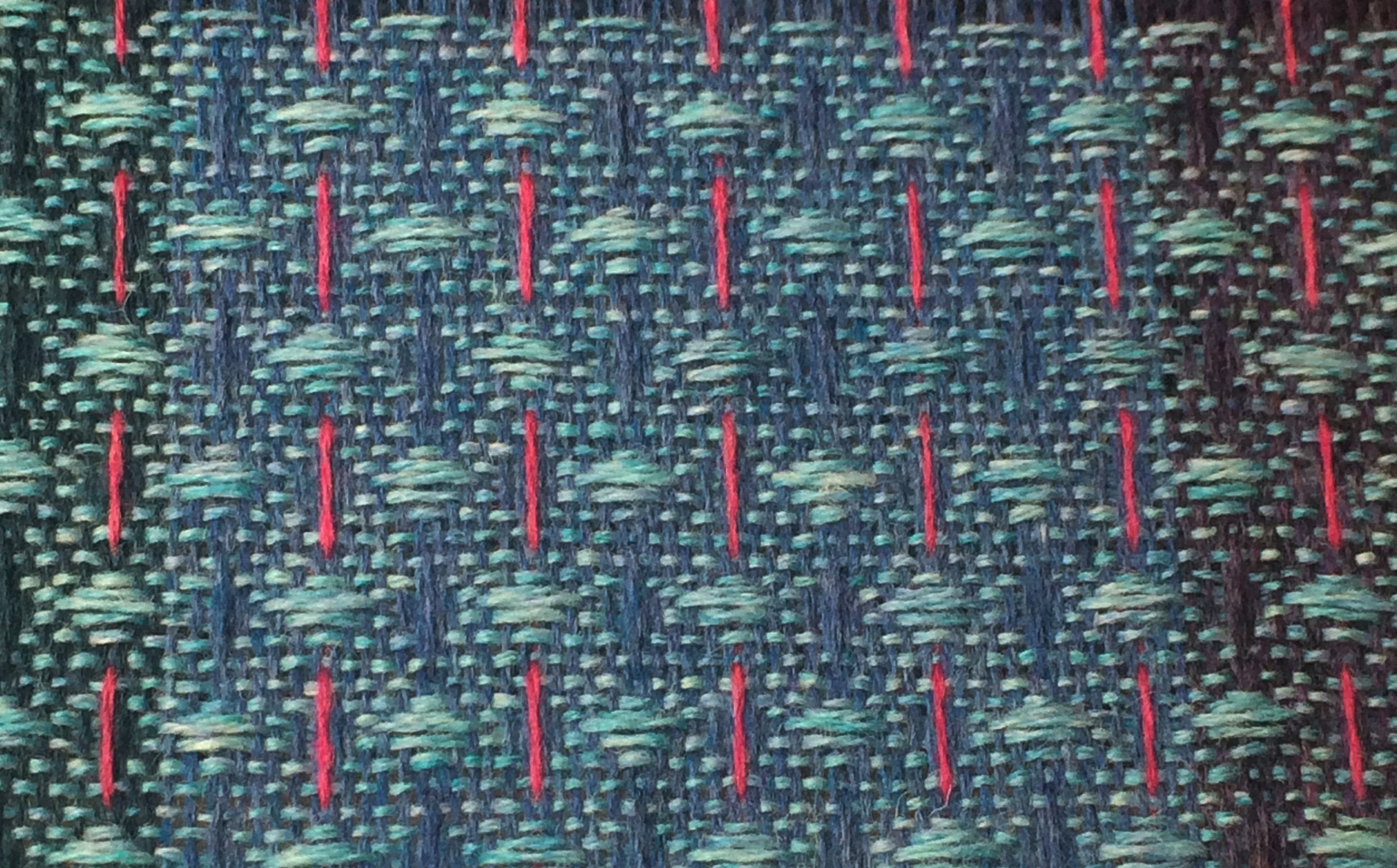

It is usual for security blankets to be invested with their own personality. Tess, now a journalist, was inseparable from Bider in her childhood. “I still have it in a basket in my room.” Bider is a piece of a pinkish checked brushed cotton sheet, much faded and the object of a great deal of love: “it was the feel and smell of Bider – I remember I used to get very upset when Bider was washed, and Mum would do it a little secretively, I’d be sad its musty smell was gone afterwards. It must have just smelt like me, I guess because I slept with it. I can’t recall exactly, but it was deeply comforting to sniff. I used to put it in the freezer during summer to make it cold and then put it on my cheek to cool down and I really liked that.”

It was also the feel of Bider that was important: “I’d wrap it around my hand while I sucked my thumb and fiddled with it and I liked the different textures. The main part of the blanket was soft but the edges were very special. They were sort of crispy and all creased up on themselves, and I’d run my fingers through the creases to make them unfold and I would do that over and over again because I liked the crunchy feel of it. It would make my head feel all nice and fizzy.”

“Bider was ultimately just hugely comforting to me. I didn’t give it a personality or anything or think it could talk, but it seemed slightly sentient to me like we had a connection and I really loved and cared for it and would get upset if it was lost in case it was cold or scared.”

“I guess it was a special thing that was very connected to me. It’s funny to think about it because it was so much just part of my life that I forget that specific thing isn’t part of every child’s life.”

“I love dog kisses – they are soppy

but I really love Bider”

Tess on Bider, aged 5

So apart from the pure transporting joy of a comfort blanket what’s going here? Do textiles have greater emotional power than other materials? Bruce Hood of Bristol University and Paul Bloom of Yale University say that children intuitively believe that comfort blankets possess a unique essence or life force, what Tess describes as “slightly sentient”. Hood says: “We look at them almost as if they have feelings. The children know these objects are not alive but they believe in them as if they are.” Which explains why only one piece of cloth will do and why it is extremely hard to replace.

It’s also a very normal part of childhood with up 70% of children developing strong attachments to toys or blankets. In the language of psychiatry, these are described as ‘transitional objects’ that help children move towards independence. They are much more common in western countries where children are expected to separate from their parents for sleep early on.

There is widespread understanding that it is the feel of the textile that is essential in giving comfort. The knowledge of this, although often unspoken, runs through our lives, when we can’t be given a hug by someone we love, a textile is the closest we can come to replicating the feeling of comfort, and we feel we can offer that essential security to someone else by giving a cloth.

In the early 1990s, my mother and I ran a Saturday blanket collection for the Kurds, who were then trekking into the mountains in deep winter to try to find shelter from Saddam Hussein’s murderous air attacks. We collected blankets all morning and didn’t have time to notice everything that was handed into us. But at the end I turned over a handmade patchwork quilt. I didn’t see who brought it. One side was brushed cotton, a striped winceyette, and the other side a melange of cheerful cotton prints pieced together. It looked old. I thought it had a history and wanted to know more. I made a donation to the campaign and rescued the quilt. It has a hand-written label in biro which says “WVS, Winona Circle, Grace United Church, Gananoque, Ont, Canada”.

It was years before I realised what it was when I saw one like in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s wonderful exhibition: Quilts 1700-2010 Hidden Histories, Untold Stories. In the Second World War, Canadian women made hundreds of thousands of quilts for children in Britain who were bombed out of their houses often under the organisation of the Canadian Red Cross. The children would be left sometimes with nothing but the clothes they stood up in, and to comfort them they would be given a handmade quilt. They were also distributed to evacuees, women’s land army workers, hospitals, convalescent homes, and children’s nurseries. Most of them have not survived, but the British Quilters Guild says: “of those which have, many are treasured by the families who own them, evidence of the kindness of strangers in a difficult time.” The one I have had evidently done its job comforting some-one and she or he wanted to pass that comfort on to another generation in need.

Quilt

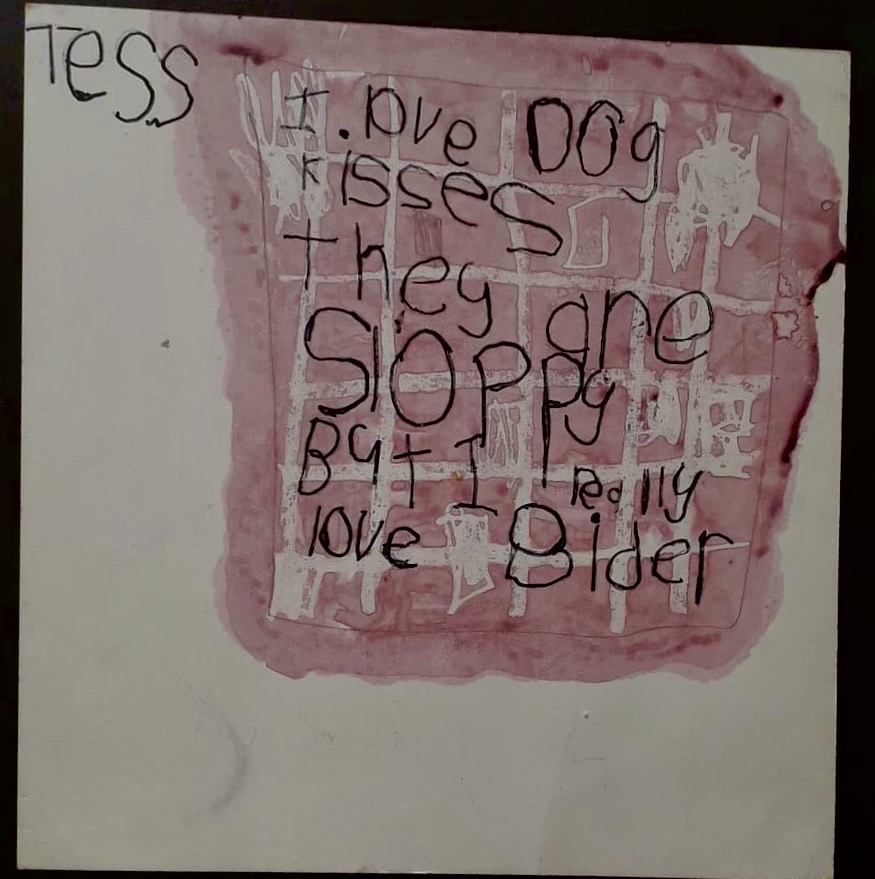

This action conveys perfectly for me the power of textiles to connect us at a deep heart level with events that took place decades or even centuries ago. In one of the green squares London is known for, sits the Foundling Museum on the site of what was once a vast orphanage – the Foundling Hospital. When mothers brought their children there – often in desperate circumstances – they would attach a small piece of fabric torn from their clothes or from the child’s clothes, and keep a similar patch themselves. In an age when many were illiterate, it was an effective way of identifying each infant and its mother.

The Foundling Hospital kept every piece and recorded them in leather-bound billet books – they now belong to the Coram charity. In 2010/11 the Museum showed these fabrics in an exhibition called Threads of Feeling. It is impossible to see the tiny scraps of material and the little mementos with them without being overwhelmed with sadness and a sudden understanding of the desperation of the mothers handing over the infants they had carried and given birth to, never to see them again or to know what happened to them. There is a cruel finality to this that the scraps connect us to. These would have been children born out of wedlock, or as a result of rape, or simply into a family with too many mouths to feed. Very few were ever reclaimed, but hundreds of years later the textiles are a visceral reminder of how it must have felt to have to do this.

Identifying scrap for child

left at the Foundling Hospital.

Toffee

When we think about textiles and their power to console and comfort us we are thinking about feelings derived from feeling. The two words come from the same root. Felan is the old English word which means both to touch something and to perceive or sense something. This connection makes intuitive sense, when we touch something it enables us to feel something whether we are summoning a ghostly memory of a parent’s love or fulfilling a primeval need for shelter and safety in our own caves.

This does not fade with childhood, not for everyone, and in the UK it seems remarkably common for adults to sleep with soft toys. Bruce Hood from Bristol University thinks that up to a third of people do this, more women than men, because, he believes it’s more socially acceptable. I confess to still having a childhood teddy bear, Toffee, on a shelf just beside my bed. He’s old, one-eyed, and balding. He was given to the family by an uncle who was very kind to us when we were children. The uncle is long gone now but the bear still gives me a sense of the loving childhood I was lucky to have. He also gives me an understanding of the span of my life. We grow old together and as he becomes more ramshackle I do too.

Textiles have a unique power to hold memory for us, both because of their feel but also the form they assume by use. Who has not looked at the shoes or clothes of someone who has died and seen their living form forcefully held within their jacket, their arm-chair, or their blanket?

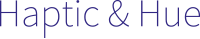

At the moment – a time of a global pandemic – I am making laundry bags for NHS staff and care workers to wash their clothes in, in an attempt the reduce the risk of infecting their families when they bring their uniforms home. I will sew a handwritten label into each bag in the hope that it will comfort the user. Who knows where this will end up and what powerful memories it will hold in future for the person who receives it.

© Jo Andrews 2020

.

Laundry Bags for Frontline Staff

Covid Crisis 2020

About the author

Jo Andrews is a weaver and writer. She has been weaving for over twenty years, slowly expanding her skills and the range of weaving she makes. At the same time she has been reading and thinking about the influence of cloth and cloth making on history and trade. She is the founder of Haptic and Hue.