Coarse Shifts & Fine Silks

What Clothes Tell Us About America’s Founding Fathers

Episode #36

This edition of Haptic & Hue is about the clothes of a community, the community that lived at Mount Vernon in America when it was the home of George Washington and his wife Martha. George is a hero to Americans as the general who commanded the Revolution against the British and went on to become the first president. But what do his clothes tell us about him as a living, breathing person? His estate, Mount Vernon, was not just home to him and his family – more than 300 people lived and worked on five farms there. Too often the focus of researchers and historians in the past has just been on the textiles and fabrics of the rich and powerful, but clothes can tell us a good deal too about the poor and dispossessed and we can look at the fabrics and the textiles that were used to dress everyone at Mount Vernon, from the Washingtons themselves to their field workers and labourers.

The people you hear in this episode are:

Amanda Isaac, Associate Curator, Mount Vernon.

Kathrin Breitt Brown, Historic Costumer and Lead Interpreter, Mount Vernon

Liz Millman, Director of Learning Links International.

Mount Vernon regularly exhibits examples of the clothing in its collection in its museum on a rotating basis. Most of the items held in storage can also be viewed online at https://emuseum.mountvernon.org/collections. Here is the link to the textiles specifically: https://emuseum.mountvernon.org/collections/45515/clothing-and-textiles/objects. Special focus groups and researchers can also make appointments to see the collection in storage, and it is a wonderful thing to do if you get the opportunity!

If you would like to find out more about Welsh Plains – the original project was called From Sheep to Sugar There is also a Facebook page which you can find at https://www.facebook.com/welshplains/ There is also an interesting lecture by Professor Chris Evans from the University of South Wales on Welsh Plains and the role it played in the economy of Wales: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxdCWFMQJz0

You can follow Haptic & Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic & Hue name.

Mount Vernon – the Mansion

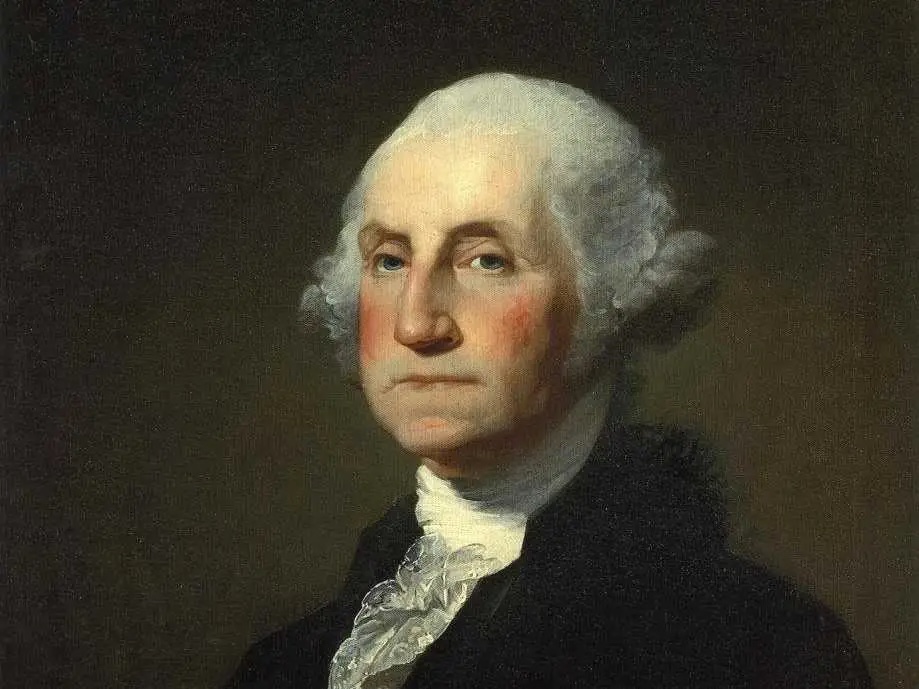

George Washington

Martha Washington

The Garden at Mount Vernon

View over the Potomac

Amanda Isaac and Jo in the Storage Vaults

Martha Washington’s Bathing Costume

Sleeve of Dress – Fabric Designed by Anna Maria Garthwaite

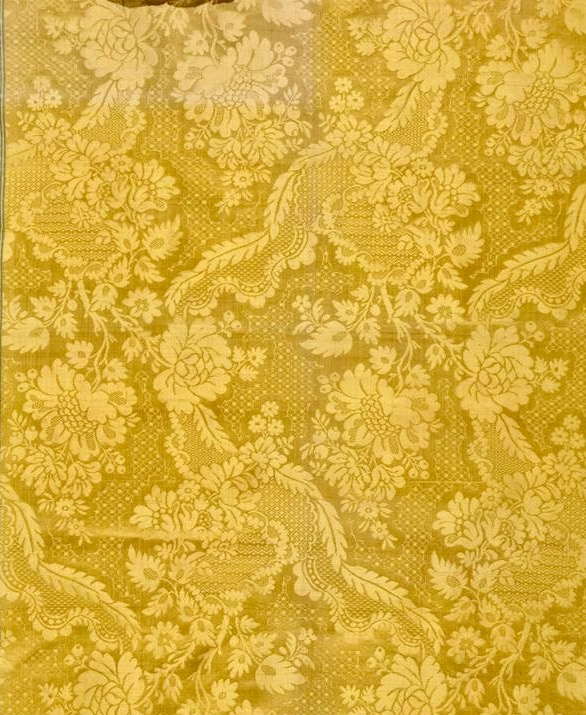

Yellow Silk Damask from Spitalfields

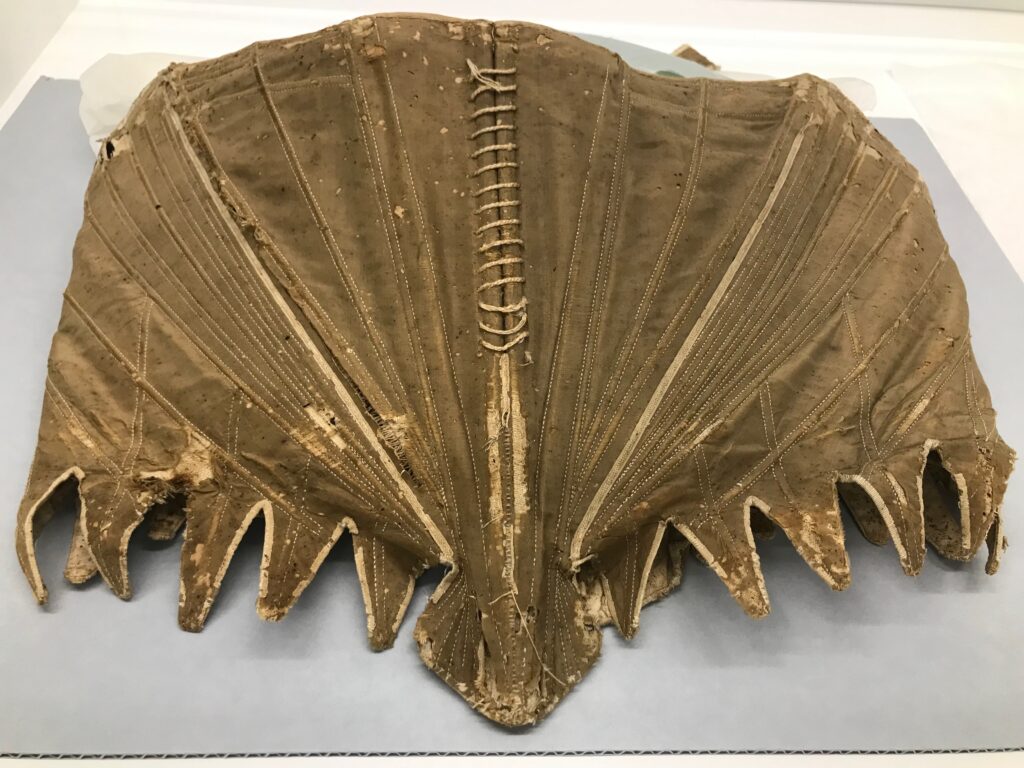

Martha Washington’s Stays

Martha Washington’s Stays

A Fragment of Martha Washinton’s Wedding Dress

The Spinning House in the 1930s

Kathrin Breitt Brown and Jo in the Spinning House

A Hog Island Sheep

Inside the Spinning House – with replica Enslaved Worker’s Shift

Wool Hand Dyed and Spun From Mount Vernon’s Own Sheep

Liz Millman

Coarse Shifts and Fine Silks: Script

JA script: One of the extraordinary things about clothes is that they open the door on the past in a way few other things can. Ever since human beings covered themselves, tens of thousands of years ago, textiles have been our second skin, protecting us, warming us, and allowing us to decorate and display ourselves. Textiles travel with us through life bearing the scars of our failures and the triumph of our hopes. How others dress themselves or were dressed by others helps us to see things in an honest light. This episode is about what textiles tell us about privilege and dispossession, about slavery and landowning at the time of America’s Founding Fathers.

Amanda: I think textiles ground us. They are fragile, but they endure hundreds of years, whereas humans barely can make it to a century. They’re so, they’re durable, they’re tactile. All of the grand ideas we may build up in our heads about what really happened. These bring us back in touch with reality. Sometimes it is grander than what we thought. Sometimes it is more humble than what we thought.

JA: Amanda Isaac works with the textiles of two of the most famous people in American history, George and Martha Washington, at Mount Vernon, their home in Virginia. The Washingtons are giants of the American story, George the successful military commander who beat the British in the American War of Independence, was one of the Founding Fathers and America’s first President, and Martha his wife, America’s first, First Lady. So much has been written and said about them, it’s hard to imagine that there is any way of understanding, at this point, who they really were, as living breathing people, so encrusted have they become by legend. But their clothes take us closer to them and tell us stories about who they were that would not otherwise be accessible. That’s what this episode is about in part – seeing how clothes can take us behind the façade of a public persona – But it is about more than that because Mount Vernon – the plantation they owned – was not just their home it was home to more than 300 people in total. Many of those were enslaved people, others were contracted craftsmen and women, hired labourers, and day workers who came in from the locality. And one of Mount Vernon’s primary functions as a farm was to produce textiles. Sheep were kept and flax was grown in the hope that those who lived there, apart from the Washington family, could be clothed from the land. One of the aims was to make it self-sufficient in cloth. So, this episode is about the Threads of Survival at Mount Vernon and what they tell us, not just about the Washingtons, but also about the entire community that lived and worked here.

Welcome to Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles, my name is Jo Andrews, and I’m a handweaver interested in what textiles tell us about the story of humanity and in particular, what they have to say about the often unrecorded lives of those who make cloth and fabric. I visited Mount Vernon at the height of last summer.

Recorded audio at MV JA: It’s a hot day at Mount Vernon high above the Potomac River in Virginia. This was the home of America’s first president, George Washington victorious general of the Revolutionary War against the British Crown. It’s a beautiful spot and something of a shrine for Americans, more than a million of whom come here every year to learn more about this man who has become a hero to so many.

It’s a miracle in many ways that there is anything to see. For years after the Washingtons’ deaths, Mount Vernon slowly deteriorated until one day in the 1850s a woman called Louisa Cunningham floated past on a boat, on the Potomac river, and looked up at the dilapidated mansion. She wrote to her daughter Ann Cunningham, that “seeing that the men of the United States were unwilling to save the estate, perhaps the women of America should do so instead”. Undaunted by the American Civil War, Ann and others raised the $200,000 they needed in one of the country’s first-ever popular fundraising campaigns. Ever since then the Ladies of Mount Vernon have run this establishment and they still do today: Here’s Amanda:

Amanda: One thing to appreciate is when the Mount Vernon Ladies Association got started, they did not have a lot of money. They knew they had this aging structure that was desperately in need, in need of repairs. They had launched one of the earliest and largest grassroots funding campaigns, and they managed to save the house, but then the Civil War broke out, and that, of course, changed everything. So the priorities at first were about the architecture. And these women, I would say they were needle workers themselves. They were very in touch with the value of textiles in that regard. But the first priority was getting the house and getting the furniture in. And it was only later as they got those things in shape if you will, that they had the opportunity to begin to think about, well, what, what would be the best curtains or bed covers and things like that. And much of those early acquisitions were gifts because they didn’t have a lot of funds to go out and purchase things. And they, as they could, they consulted with the experts in the field at the time. It is known that in the 1930s and forties, they looked to the curator of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Gertrude Townsend, to help them identify appropriate 18th-century textiles and to bring those in. And they did. And it was fantastic for that era. Shortly after that, though, philosophies changed again, and the realization that wait a minute, these are 200-year-old textiles, rather than putting them in a historic structure that is subject to dirt and dust and fluctuating temperatures and sunlight damage, we need to care for those differently. And then the whole shift began to take place moving to the use of reproduction textiles in historic museums.

JA: And then the thinking changed again and people began to understand that textiles had new and different stories to tell:

Amanda: So, the understanding that textiles, particularly clothing, is not just an illustration about a historic period, but tells us about those individuals about the, the economics and the relationships and the physicality of these. this whole understanding of material culture as history that has been, I think the new understanding of textiles as material culture, as artefacts that have important intrinsic information about the individuals who made them and used them, the relationships that brought them from one place to another, of the economics. All that of that type of historical thinking and philosophy. That attitude is new to this generation.

JA: And that led to a re-assessment of the textiles that Mount Vernon holds:

Amanda: In, 2015, we started looking at the textile collection with a new eye. And there were several important pieces that were very well-known and well-published. Martha Washington’s gown, George Washington’s coat, for instance. And that had been exhibited on a regular basis, but there were hundreds of other items, dozens of accessory types of stockings and pockets and caps, and then hundreds of these fragments from their clothing. There was a whole wealth of other material that because of the state of it and because it was so delicate, really hadn’t been researched or exhibited, or very well known. But in order to realize we had all those treasures we had to sort through a significant amount of other material that had accumulated over the course of the 150 years that Mount Vernon Ladies Association had been collecting.

JA: And that trail leads back to the reality of what it was like to be Martha and George Washington and places them back in the context of their age:

Amanda: Yes. Well, it’s what I find so interesting about the textiles and what they tell us about George and Martha Washington is, in many respects, they confirm the shape and the sizes of the man and the woman that these are ordinary humans. They are not they’re not divinity, they’re not anything superhuman, any superheroes. They were humans subject to all the trials and tribulations of being stuck in a body, you know, on this earth. And on another level too, the Washingtons were elite. They had incredible wealth. Washington was one of the richest Americans at the time of his death. But at the same time, their choices in terms of their garments, their furnishing, textiles, were relatively modest, and the emphasis on relative compared to what other elites had access to and decided, to use in Europe and England even in the far East. So, textiles really have that corrective property on your historical imagination and understanding.

JA: We can see that the Washingtons cared greatly about their clothes and the quality of them – they wanted the best:

Amanda: We see that in their writings and their correspondence of the back and forth with, with tailors and mantua makers or the lace sellers, Mrs. Washington gets particularly frustrated with a woman who tries to sell her lace that is not of the finest quality, is not what she, she thinks she’s paying for. And they are very aware of those subtle differences in quality between grades of lace or grades of linen or silt. More so than we, we might think today. And very in touch with changing fashions. What, is the latest in London? There was continual tension in the battle between the colonists and the merchants in London, the merchants in London wanting, to get goods out and out of their shops. And the folks in the colonies wanting to get the most fashionable, not just what you could offload to us type of goods.

JA: Martha Washington bought Spitalfields silks, woven by Huguenot weavers in London – which we explored in episode 28, and Mount Vernon still has pieces of this. It’s the first time I have ever seen a piece of fabric designed by the great Anna Maria Garthwaite, the first known professional women textile designer. Mount Vernon also holds parts of Martha’s wedding dress from her marriage to George Washington – a glorious yellow silk lampas that probably dates from the 1720s. It also startled me that this great hero of the American Revolution, George Washington, had his tailor in London and ordered his clothes from there.

Amanda: Before the revolution, they’re wanting the best, they’re wanting the finest quality of tailoring and fit. And at that time, England is the place to go because of course, here in Virginia on the banks of the Potomac, you are hundreds of miles from the nearest urban centre. The biggest one at that time would’ve been Philadelphia. Not easy to go shopping and get what you needed there. Williamsburg is several hundred miles in the other direction. But again, it’s a small town. And so the shortest route in some ways is to go across the ocean by a ship that you can get in a few months what you need and what you know, is the best quality in the latest fashion. And all after the revolution, though, particularly as they’re traveling more, and then during the presidency when they’re in New York and Philadelphia, they do shift to using local tailors and dressmakers and all that. Now they’re still importing their fabric from, England, but there those merchants are also getting things from France and advertising the latest French fashions.

JA: The collection at Mount Vernon is extensive and beautifully cared for in special storage rooms. It has everything from George Washington’s trousers to Martha Washington’s needlework and it was a privilege to be shown around it. There are two pieces though that caught my heart. They both belonged to Martha Washington. One is her bathing gown which survives as an entire piece. This is a long shift in an indigo and plain linen checked weave, designed for maximum modesty:

Amanda: This is the sort of piece where we, we wonder, we don’t know the maker. Was it done by one of these local seamstresses? Was it done here on the estate by enslaved woman? At that era, it might have been someone like Betty, who was the seamstress and close attendant for Mrs. Washington. It’s very simply constructed just like a shift would have been, but longer. And then the innovative part of this is in the hem. It has these circular weights to hold that hem down as you immerse yourself in the bath, in the water.

JA: This is a very humble piece, as far removed from a grand silk gown as you can get. But it has a sad story behind it. Martha’s daughter, Patsy, suffered from epilepsy and her seizures got worse as she grew older. Desperately seeking a cure, the Washingtons took her to Berkeley Springs.

Amanda: So many of the Washington garments don’t survive because they were reused as would have been typical by extended family members. And then the other part of the Washington story, because of their celebrity, not only were fabrics reused, they were also cut up and given away as souvenirs and relics. So most of them don’t survive. But with this one,, we get the sense that after that 1769 visit, when they go to the springs with Patsy, they try the waters. It evidently doesn’t have any effect. It isn’t worth the trip. It’s quite a hike to get out there. And so this piece gets packed away. Maybe initially she thought she’d unpack it and they’d do a visit next year, but it never gets pulled out again. And it stays unused. Patsy dies in 1773, just a few years later. And you also wonder, did this, you know, have all those memories and associations with that visit with the effort that she put in to save her daughter? Was it, saved because of the tragedy that it was associated with?

JA: The other item, which is deeply personal is Martha Washington’s corset, her stays. I have rarely seen a textile that brings a person so much into focus.

Amanda: These are Martha Washington’s stays. So perhaps the most intimate look, at who she was as a human, a vulnerable human. The shaping of them is interesting. They are not fully boned. And this is typical of what you see in later stays in the 1780s and nineties where you’re having less structure in the stays and you’re having a little more structure in the garments themselves. The measurements and the shape of these actually lines up very well with some surviving gowns we have of hers from the 1790s. They’re all covered in silk boned with baline lined in linen, bound with silk. They have these lovely triangular tabs along the edge, and you’ll see that they are, they’re not pristine. If you start to look where the arms are, you’ll see sweat stains. You’ll see places where they were mended and repaired, and where the baline broke through and new linen had to be added. So this is a record, of her movements, her life, the work that it took.

JA: Part of my astonishment is that this garment was saved at all. How many of us put aside and carefully preserve our grandmother’s well-used underclothes?

Amanda: It truly is amazing for, for all the reasons you, you say this is, this is so intimate. This is your undergarment is so utilitarian in a way, but it was saved by her granddaughter and Martha Custis Peter, and of course, at that time, Martha Washington had become a celebrity and was the founding mother. And so not only was this a record of her grandmother but also of this great personage who they all were looking up to. Still, I think it’s a very personal, a very female thing to do, to save something like your, your grandmother’s stays. And thankfully that family didn’t lightly throw anything out. They held onto things. And we are enormously indebted to them because now we know what the real Martha Washington looked like. So much of history and history writing tends to inflate these historical figures to build them up to great proportions, or in the case of Mrs. Washington, to reduce her to a more diminutive personality, almost to this fairy-like creature. And, this brings us back in touch with the reality.

But Mount Vernon was much larger than just the Washingtons. There were several hundred people who needed to be clothed and fed. The largest number were the enslaved. In 1799 there were 317 enslaved men women and children on the Washingtons’ five farms and about a hundred at the Mansion House, which was the hub of the property. The custom here was that each enslaved person was given two outfits a year. There were also indentured and hired white servants, ranging from clerks, overseers, gardeners, weavers and secretaries who had different agreements which might have specified clothing and laundry allowances. That’s a lot of cloth and the Washingtons tried to do this as economically and cheaply as possible, which is where sheep come in: Here’s Kathrin Breitt Brown, the Historic Costumer and Lead Interpreter at Mount Vernon.

Kathrin Breitt Brown: Well, right now we have Hog Island sheep. And they are genetically as close to the breeds that we think Washington had here. The Hog Island sheep have a bit of a history. So there’s a little part of Virginia that actually just off of Maryland into the Atlantic Ocean. And there is an island named Hog Island. And rumour has it that sheep, the Hog Island sheep inhabited that island, the very sturdy breed of sheep. And it was the last place that the ships stopped on the way out to sea. They would pick up the sheep and then slaughter them en route. So they had food. Now Washington is using the sheep for several purposes. They’re incredibly important to his textile industry. They produce better than the average. He has a breeding program in place. He’s trying to create more wool off of his sheep. They produce just over five pounds each in the good years. Not all the years are good years, when they’re well cared for is what he writes about. The average seemed to be at least a little bit less than that. And there are some years where there’s only a couple, few pounds, and it is almost always the years he’s not here. He is always concerned about the enslaved pilfering some of the skirting I’m sure you know, when you shear sheep, you got to get all those really mucky parts off and they seemed to be rather generous with that at times.

JA: And there’s flax too growing in the fields. All of this is harvested and taken to the spinning house, which is one of the original outbuildings and is still here. The end product is most likely coarse woollen and linen cloth for the enslaved. It is one of the many tragedies of slavery that the individuals who were enslaved are hard to trace, the record is close to blank and yet here at Mount Vernon, we can catch glimpses of the people who worked for the Washingtons, but they are only seen through the eyes of others who wrote about them or accounted for them. We never hear their own voices.

Kathrin Breitt Brown: So there’s record of an enslaved man by the name of Long Jack, who evidently is quite quick at processing the sheep, shearing them and then the fleece goes to Dolci and Vina who are working out in the washhouse just down the lane from us. And Dolci is also a spinner, so she knows how to wash wool. Because you know, if you don’t wash wool right, you’re going to felt it up, and Dolci and Vina wash it, and then it is being given to someone to card. But we’re not sure who. Washington kept pretty careful track of what every adult enslaved worker was doing every day. We have no record, at least by my understanding of who was doing the carding. But we know that one of Washington’s spinners, Miss Kitty, had nine daughters. Seven of them went on to be spinners. and the spinners were almost always enslaved women. But every once in a while, if Washington is a little bit behind, he might bring in a neighbour woman to help spin as well.

JA Anthony and Wally, two enslaved men at Mount Vernon were skilled weavers working at looms in the years before 1781, but then a British ship arrived in the waters below the house:

Kathrin Breitt Brown: In 1781, the HMS Savage anchors out there in the Potomac River. And when the Savage leaves, it leaves with I think 17 of Washington’s enslaved workers. And the two weavers are part of them. They are never found again.

JA: And there’s an interesting and little-known part of the story here. During the American Revolution, the British offered freedom to enslaved men and women who left their American masters, to destabilize the American economy. The arrival of the HMS Savage presented an opportunity for the enslaved men and women left at Mount Vernon, who were then under the watch of a white manager, while George Washington was away leading the Continental Army. Many of these former enslaved people later settled as free people in Canada and Trinidad. It cost Mr Washington his weaving expertise which he had to find elsewhere – here’s Kathrin.

Kathrin Breitt Brown: He loses his weavers. Thereafter, there are periods where there doesn’t seem to be a weaver in residence here, either as a hired indentured or enslaved. So itinerant weavers were likely coming in. And then since he’s producing clothing for the enslaved, we now have to pass that fabric off to tailors. The seamstresses were almost always enslaved women again, being supplemented by neighbour woman on occasion. Tailoring a more complex job, of course, than the seamstress putting seams together so they could do things like that shift we see over there. It’s all geometric shapes, very easy to cut and assemble, but breaches: much more complex. So, there are records of a particular tailor by the name of William Carlin who comes in to do measuring and cutting, and then probably passing it off to the seamstresses.

Here are skilled people who spin, sew and weave. What else did they make? What happened to the offcuts of the fabric they were cutting out, and that extra skirting from the sheep fleeces. The record is not quite bare here. The great American researcher on Black quilting, Cuesta Benberry, records in her book, Always There: The African American Presence in American Quilts, a Sugar Loaf pieced cotton quilt made by Diana de Gadis Washington Hine, a former slave born at Mount Vernon in 1793. There must have been a good deal of other material goods as well that are lost to us. The records do show though what the enslaved field workers got in terms of clothing every year.

Kathrin Breitt Brown: So the field workers seem to get essentially two outfits a year. Two so for summer and winter, two shifts, as I said, that’s a shift over there for the women, two body shirts for the men out of linen or Osnaburg, which is very coarse linen coming initially from Osnaburg Germany. But eventually, it’s made in a variety of places. And one pair of shoes and two pairs of stockings, that’s what they’re getting. That’s all on an annual basis. Oh, and a jacket, I’m sorry, a wool jacket.

JA: And no choice about it. But even with that tiny provision, the farms themselves were unable to produce enough homespun: Here’s Amanda:

Amanda: But you know, the economics of this were, no matter how hard the Washingtons tried here on the plantation with slave labour to produce cloth, they could never do it as fast and as efficiently as some of the operations in Europe and the Baltic, even in Russia and in England. And so all that is to say, we know that the Washingtons, at the same time as they’re producing cloth here, they’re also importing all different grades of cloth as well, and using them for different purposes.

JA: And just as they went to Britain for their luxury cloth, it is likely that the Washingtons turned to Britain to purchase cloth which was called “negro” or slave cloth. One of the areas this was produced in was thousands of miles east of Mount Vernon across the Atlantic in the hilly uplands of North and Central Wales. Here’s Liz Millman from the Welsh Plains or Brethyn Online Research Project:

Liz Millman: Welsh Plains was a cloth produced in the 1700s in Wales. It was handwoven by local people on their rented property. Wales was a country that had been taken over by the British way back in the 1200s. So, there were English landlords and Welsh workers, so Welsh Plains was the cloth that was produced on hand looms in little cottages, and later in special buildings which were easier to manage the increased production of a cloth that became extremely popular as one of the many fabrics that was needed to clothe enslaved workforces in the Caribbean and in America and other parts of the world.

JA: The cloth, which was made from the coarse wool of hill sheep, went from the valleys of north and central Wales up to Liverpool, one of the great Atlantic shipping ports and a major centre of the slave trade before it was abolished.

Liz Millman: And at this stage it was a transatlantic triangle. So ships from, Liverpool went to the West African coast. There, the cloth was used for trade purposes so that the local African, people would, require blue cloth or red cloth. They were very specific, in what they required. They very much valued this cloth, Welsh Plains, and so that was an interesting area of research, but we also know that the cloth was required, in the Caribbean and in the Southern States to cloth enslaved workers. And we also know that some of the enslaved, some of the plantations, also tried to replicate this specific cloth because its qualities were that it was hard wearing and cheap.

JA: Conditions in the country areas in Wales were hard – although nothing like enslavement:

Liz Millman: Poverty in Wales was a real issue. The landowner had good properties, but the ordinary people living in rural Wales were subsistence farmers. They were just trying to make a living. It was common for farmers and their families in Wales to undertake the production of cloth during the winter seasons when it’s very cold and nothing grows, and then to farm their land in the summer seasons. So advertisements to work on the farm would often include that men were able to weave because the weaving part of the production of the cloth required men who were strong enough to be able to literally, throw the shuttle from side to side. So the factors were offering incentives to local farmers to buy new looms and to have more workers be tempted to come into little towns, to produce cloth there. And so the dependency on production of the cloth, became an issue because then when the cloth was no longer required for the trade, then there was real abject poverty. And in a way it’s probably to this day, Wales still suffers from that story of at one time being able to create a reasonable lifestyle, but then the families must have really suffered, and then so many Welsh people either emigrated, so there would’ve been Welsh weavers going to America or Canada or Australia.

JA: Liz says that as time went on, before the Slave Trade was abolished, the Welsh workers knew where their cloth was going:

Liz Millman: They certainly did towards the end, because there were big campaigns in Wales against supporting the slave trade because it wasn’t just the cloth that was, an element in this, there were, local families who had plantations overseas about whose activities and income would be understood. Putting two and two together about the use of Welsh wool and cloth for clothing enslaved workers might have been a bit difficult, but that it was a part of the trade. And gradually over the years, the trade would have become better and better understood as being a fundamental part of the economy.

JA: Wales wasn’t the only area that produced this kind of cloth, Scotland produced Osnaburg, there was Kendall cotton from the Lake District, which was in fact wool, and similar cloth from Penistone from Yorkshire.

Liz Millman: So really right across Britain, there was activity going on in small communities, and larger communities that was in some way connected with supplying goods for the slave trade, but also for receiving goods into Britain, the sugar, the tobacco, these were all huge industries then to process and distribute those products in whatever format. The market took the cocoa, the rum, whatever it took, the people were involved. And from quite an early stage there was objection to the slave trade. And so, people would’ve known that this was an aspect. But it’s difficult to watch Georgian drama with all these gorgeous costumes in all these stately homes, and to realize that something big must have been going on, if these people actually didn’t have to work, they could just loll around <laugh> and, and enjoy being wealthy. Yes, there’s a lot still to be learned about that time and for stories to be told, honestly.

JA: And just as Mount Vernon would love to find a piece of cloth that they could definitively say was grown and processed on the estate itself, so Liz Millman and the other researchers would love to find some Welsh Plains cloth too. Both of these textiles would probably look quite insignificant in themselves, but they have the capacity to tell us something important about the honest story of Britain and America, of who we are and how the wealth of our nations was built.

On his death in December 1799 George Washington stipulated that all the enslaved people he owned personally, 124 of them, were to be freed. This Martha Washington did on January 1st 1801 – shortly before her own death.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Haptic and Hue, and a huge thank you to all at Mount Vernon for being so generous with their time and insights. In particular to Amanda Isaac and Kathrin Breitt Brown, and also to Kenneth Hill who arranged my visit to Mount Vernon and acted as my guide and cheerleader – I could not have asked for better company.

If you would like to see pictures of the textiles at Mount Vernon or read a full script of this podcast, you can find them both on Haptic and Hue’s website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen.

Haptic and Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast either via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a member of the new Friends of Haptic & Hue, which costs £50 a year or £5 a month. This keeps the podcast truly independent and free from sponsorship and advertising. The first Friends’ newsletter launches in two weeks time with a look at how this podcast was put together, and an interesting musical follow-up to the episode about Mary Queen of Scots. If you’d like to find out more it’s all on the website at www.hapticandhue.com/friends.

Haptic and Hue will be back on the first Thursday of next month with another Tale of Textiles but meanwhile I will leave you with a small story from Sojourner Truth, who was a remarkable woman. Born into slavery in New York State, she escaped in her twenties and spent the rest of her long life preaching and speaking against slavery and in favour of women’s rights. Here’s is a story she told children in 1852.

“This morning I was walking out and I got over the fence. I saw the wheat holding up its head. It was very big. And I goes up to it, and takes hold of it, and you believe it, there was no wheat there. I says: God! What is the matter with this wheat? He says, Sojourner, there is a little weasel in it. Now I’s here’s talking about the Constitution, and the rights of man. I comes up and I takes hold of this Constitution. It looks mighty big, and I feels for my rights. But there isn’t any there. Then I says to God, “What Constitution?” And he says to me, “Sojourner, there is a little weasel in it.”