Lyon

City of Silk

Episode #23

This podcast explores one of the great textile cities of the world. For hundreds of years, Lyon was a byword for weaving skill and savoir-faire. The silk fabrics exquisitely woven here dressed the royal families of Europe, clothed merchants and muses, priests and politicians, courtesans and courtiers and produced some of the most coveted fabrics of the day. Come with me and explore the old and winding streets of this lovely city, the secret pathways created by the weavers to move around the district, the buildings they lived and worked in, how their children went to sleep to the sound of looms, and most of all the astonishingly beautiful cloth they made.

This episode runs for 31 minutes.

Thank you to Marion Falaise and Suzanne Lasalle at the Musée des Tissus in Lyon. The Musée is currently closed for renovations but will open again in a few years’ time. You can keep up with the progress on instagram: @museetissuslyon. I am hoping to return to Lyon for the opening of the new Musée when all the work is done!

If you are in London and wanted to see a silk weaver’s house then the Dennis Severs House provides a much, much grander setting for a silk weaver’s home than any of those I saw in Lyon. But many of the Huguenot weavers who fled to to Britain at the end of 17th century came from Lyon.

Blandine Rauzy works for the Soierie Vivante, https://www.soierie-vivante.asso.fr/ENG/. If you are ever in Lyon it is well worth a visit.

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

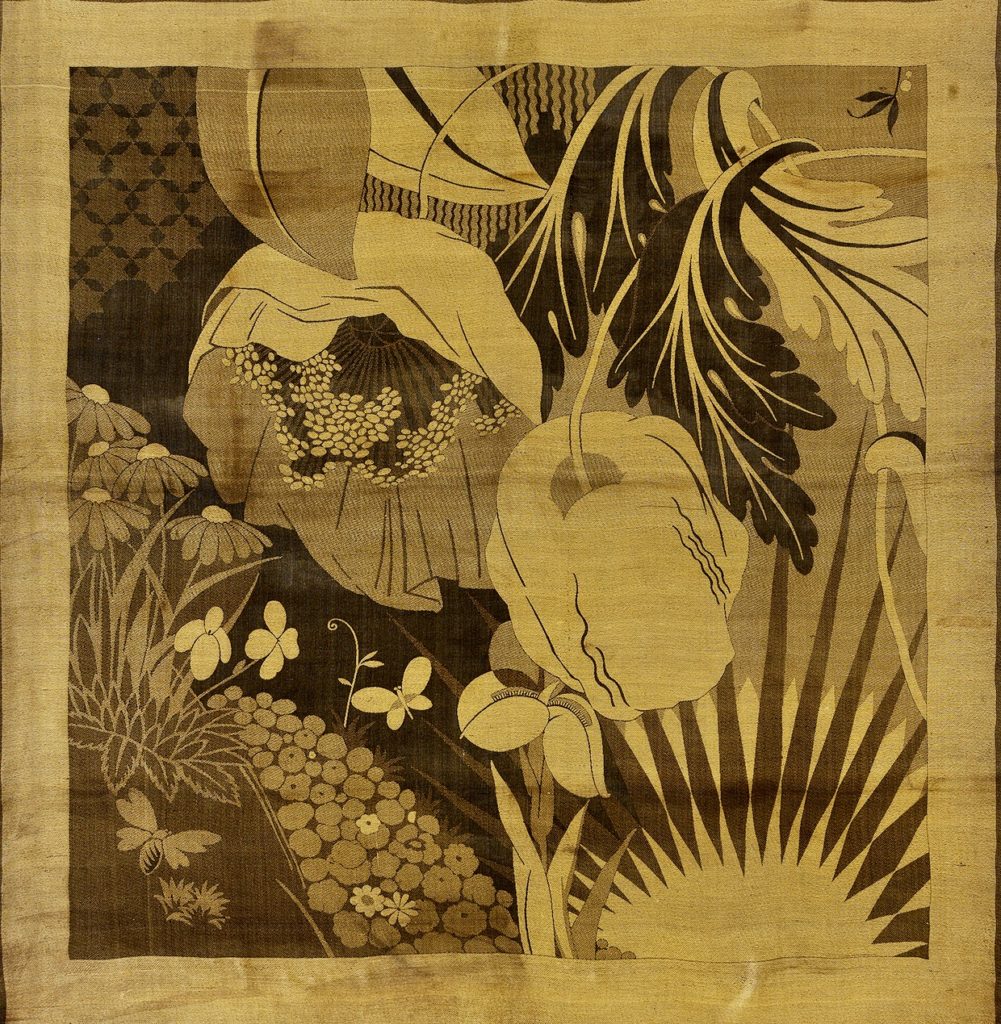

Day and Night from Francois Ducharne’s Design House

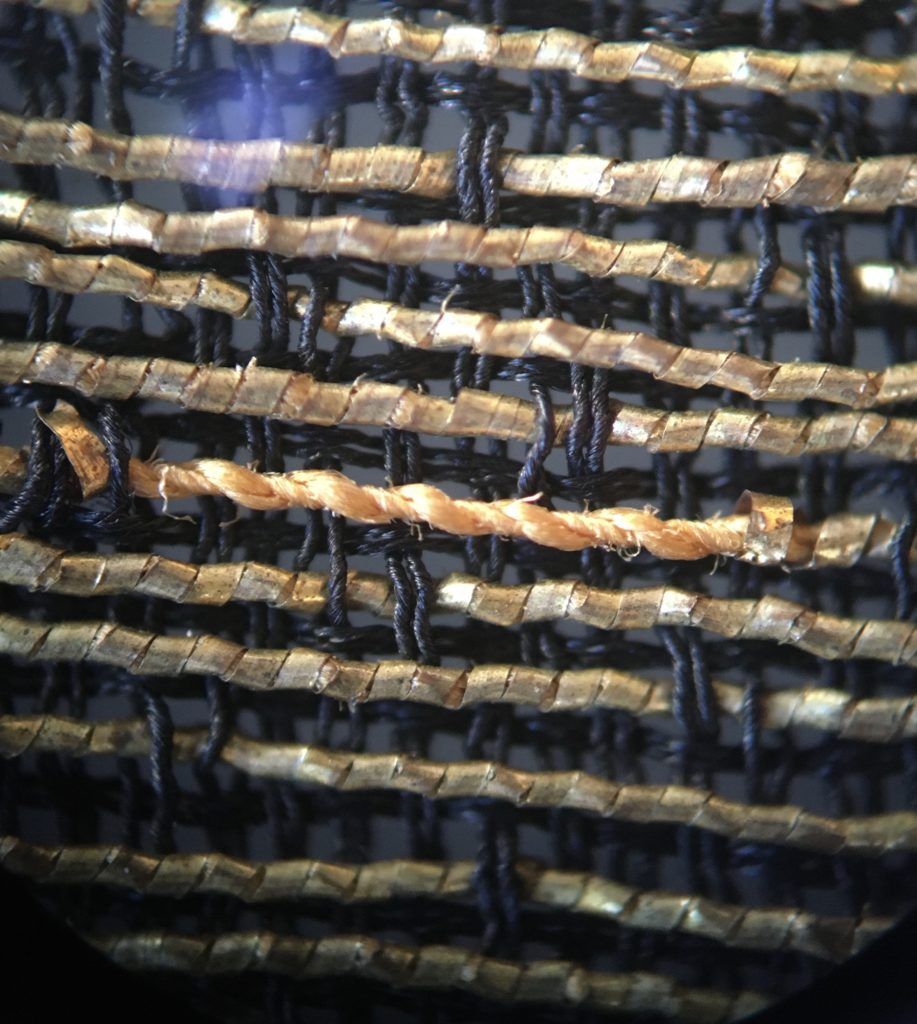

Detail of Day and Night

Safely Covering up Day and Night in the Restoration Studio

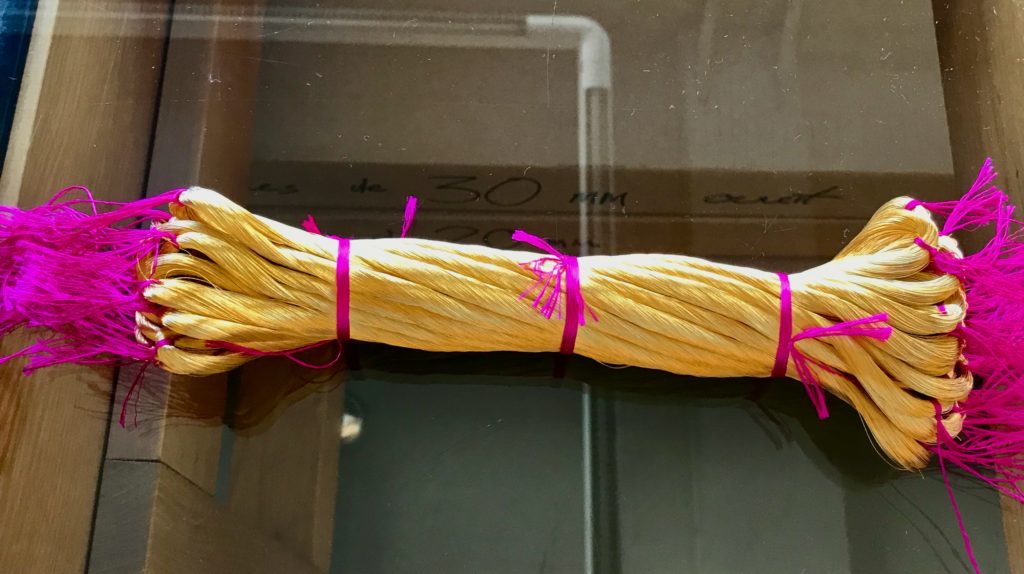

Gold Thread Made in Lyon

Suzanne Lasalle and Marion Falaise

Musée des Tissus – Being Renovated

Lyon’s Old Town

Lyon – on Two Rivers

A Traboule in the Old Town

Benedicte Roy – City Guide

19th Century Weavers’ Apartments

Workspace Inside an Apartment

Blandine Rauzy at the Soierie Vivante

Jacquard Punch Cards Sitting Above a Loom

Loom Weaving Silk

Lyon – City of Silk

Script

Welcome back to Haptic and Hue’s third series of Tales of Textiles, I’m Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver interested in the different light fabrics casts on humanity. This series is called the Chatter of Cloth and that’s because textiles are – if we can listen to them – detective stories that we can hold. They tell us a huge amount about ourselves and the world we live in. They also offer us a window into the lives of ordinary people. People whom history has largely forgotten, but by looking at what they were doing and making we can find a way to understand more about who they were and how they lived.

Join me in this episode to look at one of Europe’s great cities – one that for hundreds of years was a by-word for exquisitely woven silk fabrics that dressed the royal families of Europe, clothed Merchants and Muses, Priests and Politicians, Courtesans and Courtiers, and produced some of the most coveted fabrics of the day. Lyon is more or less in the centre of France and this episode is about how textiles shaped this city and how the city and its people, in turn, shaped and changed the world of cloth. Without Lyon, France would not have become the hub of the world’s fashion industry. Paris may be the city of couture – but it could never have acquired that status without Lyon standing behind it as its production and textile design house. In fact, it’s fair to say that it is the skills and the talents of the craftsmen of Lyon that played a central role in the birth of the whole idea of fashion, where styles change from year to year.

We are in a very grand building in the centre of modern Lyon – in the restoration workshop of the Textile Arts Museum. The building is undergoing extensive renovation at present and is closed for a few years, the sounds of construction work are everywhere. But just before the textiles were packed away and transferred to another location during the work, the Head of Collections, Marion Falaise let me in a side door to show me something extraordinary – a fabric of great beauty and skill that really makes the relationship between Lyon and Parisian fashion plain. It’s a couture scarf about a hundred years old made for a French fashion house at the height of the Art Deco period. Marion speaks French here, and she is translated by Lesley Fonlladosa.

Marion: Peut-être que vous ne vous attendez pas á un tissus comme ça, noir et doré c’est un tissu du premier desinée du vingtième siecle…..

Leslie: Jo, maybe you weren’t expecting to see a textile like this it’s from the beginning of the 20th century. So we wanted to show you a piece from the 20th century, that would show you that our collections here are very rich with more modern fabrics. It’s a scarf with very generous dimensions, two coloured, black and gold. In the middle of the composition we have two poppies that dominate the composition One has opened and the other one is still closed. And the lower part, we have a little bush with daisies and butterflies. These are elements of nature that are very stylized are completed by more geometric forms. At the bottom, a rising sun, and at the top, a starry night sky, these two elements explain the title that was given to this scarf: Day and Night

This piece is exquisite – woven in a black silk crêpe with a supplementary yarn made of gold lamella wrapped around a yellow cotton core. It gives the scarf an astonishing drape, It is simultaneously light and heavy and yes, I was given permission to touch it – briefly.

The scarf was destined for clients of the high fashion houses in Paris. At that time.

It is one of the most complex and beautiful woven textiles I have ever seen and draws much of its style from the art movements of the day. It was made in Lyon in the 1920s on a complex Jacquard loom. It has 52 threads per centimetre in the warp – that’s over 130 ends per inch, individually threaded by hand with black silk yarn highly twisted in different directions to create a flat crepe structure.

It was designed for Maison Ducharne which was set up by Francois Ducharne – who had been trained in Lyon. He took himself off to Paris to set up one of the first weave design houses that employed graphic designers to create new textiles. He worked with some of the top couturiers of the day – Paul Poiret and Madeleine Vionnet. He was also friends with the celebrated French novelist Colette:

Marion: Colette a beaucoup écrit sur Ducharne……

Leslie: Colette wrote about her friend, Francois Ducharne, quite often, she even wrote that Francois Ducharne was the man who could weave the sun, the moon and the blue rays of the rain.

Ducharne understood that if a design was going to work it needed to be adapted to its use. And that piece does this absolutely– it is a fabric completely of its time and one of Marion’s favourites in the Museum’s collection:

Marion: Je croix que je un gout personelle for cette carré…………

Leslie: I have a personal preference for scarves and we can see how you can stylize by simplifying foliage, flowers. And at the same time, it’s also a perfect example of Art Deco, with the geometric designs and the choice of the gold and black colours. So, what’s interesting here is in this piece, we have a concentration of Lyon’s textile know-how. So, one of the strong points here in Lyon was to have textile designers who understood new weaving techniques and were able to translate, transcribe their designs to a loom. That’s one aspect, but there’s also the fact that the threads and yarns used in this scarf are also a result of Lyon’s know-how. And in particular, the frisé, a gold thread that was used here, it’s a definitely a Lyon specialty. And even to this day, Lyon is renowned for this type of gold thread that is still produced here.

In fact no self-respecting member of the British House of Lords was seen without a little bit of gold thread from Lyon on his robes. And this scarf represents, in many ways the height of Lyon’s skills and its design approach. But like the annoying child forever asking questions I want to know why this happened in Lyon and who were the people who made it possible?

I’m across the river from the Museum of Textiles in the old town of Lyon – this is where the city’s story as the world’s top producer of luxury silk fabric begins. This part of the city is crowded onto the bank of the Saone river, its tiled roofs and cobbled streets framing the stone houses that face each other across narrow streets. Even today you can still see the gutter running down the middle of the lanes which would have carried everything into the river. It helps us to imagine what the smells and the sounds must have been like hundreds of years ago. These people were not rich or well-fed, they didn’t live comfortable or long lives – in fact, they lived in considerable squalor, and yet for hundreds of years, they were producing the most luxurious and highly coveted silk textiles of the day.

The first answer to the question of Why Lyon is: look at a map. It’s in a great place, it sits at the meeting of two big rivers, the Saone and the Rhone, the Rhone gives it a waterway to the Mediterranean, which meant that raw or spun silk could be imported from Spain, Italy and the Middle East, and yet it is far enough north to make it a place that the rich merchants of the north could reach from Paris, London, Antwerp and Amsterdam.

By the 1400s Lyons was the site of one of the great medieval fairs with traders coming from all over Europe and Asia Minor to see, to buy, and to exchange. But textile production is expensive, especially silk production, and for that you need capital. So, hand in hand with the textile trade come the bankers, in this case, they came from Italy which in this era had Europe’s most sophisticated banking industry. That gave Lyon the raw materials, the markets, and the capital it needed. All that it lacked then was what the French call Savoir Faire – the skill, the talent, and the know-how. And that’s where this city really comes into its own. Here’s the Museum’s Director of Textile Analysis, Suzanne Lassalle, explaining this, translated again by Leslie Fonlladosa.

Suzanne: Mais les success de Lyon explose dans le dix septieme…..

Leslie: But Lyon’s success story really starts to take off in the beginning of the 16 hundreds. Because their technical capacity and skills had been established. And they were also able to produce new designs quickly, which led to the idea of, uh, changing designs more often. The idea of fashion as it’s reflected in fabric design. And the fact that the production changes, the designs change that attracts a new clientele who were at the court in Versailles and allowed Lyon to take the leadership in this domain.

So this is where the idea of fashion is born – It’s a very long way from the fast fashion of today with new designs every week, but Lyon with its flexible system of production, its capital, and its concentration of dealers, brokers, designers, and weavers could offer styles that changed and developed from year to year, which is really at the root of what fashion means. By the 19th century earnings from Lyon’s silk cloth brought in more money than any other French export, and at its height it employed around 100,000 people not just weavers, but dyers, finishers, those involved in sericulture, traders, bankers, agents, shippers, and all the people needed to make a great industry function. But at the heart of this were the weavers and the system in Lyon meant that everything happened, not in giant industrial factories but in a domestic system. Benedicte Roy was born in Lyon, is fiercely proud of her city. She works as a city guide, specialising in its textile history:

Here in Lyon, never, we have seen a big factory of silk. In fact, the people work at home. I can compare with English system that we call the domestic system. You work and you live in the same place. It means that all the life of a silk workers was around the machine because the mechanical loom was in the centre of their life to work, but physically in the apartment.

Look inside one of these apartments – there is one that is maintained as it was by an association and the looms dominate the single room, there is a small boarded-off or curtained area for cooking and a sleeping platform above it for the whole family. It was cramped and incredibly noisy during working hours.

Look inside one of these apartments – there is one that is maintained as it was by a living history foundation – Le Soierie Vivante and the looms dominate the single room, there is a small boarded off or curtained area for cooking and a sleeping platform above it for the whole family. It was cramped and incredibly noisy: Here’s Blandine Rauszy who works for the Foundation

So in the 19th century, the traditional family is made of five persons, the two parents, two children, and one apprentice, and everyone was sleeping in the same area. It’s a sort of mezzanine. So it’s very useful because we win a room. As the ceilings are very high, we can make a mezzanine with the kitchen and the sous pent, bedroom, and everyone was sleeping, eating in this little corner. And it was also quite useful because you are directly on the place of work. So you just needed to wake up in the morning and go to work. But that means also that the, the everyday life is, uh, the, is major with the work of the looms and especially the sounds of the looms. And we said earlier that the children were sleeping in the [inaudible] in the bedroom with the sounds of the loom. And they were able to sleep only with the sounds of the room, like a lullaby. So really the looms are part of the family also and the everyday life.

This was a tough life. Each weaver was responsible for developing his own skill and craft. He was paid on piecework system. It didn’t matter how long it took to finish a piece – the payment was the same. These weren’t industrial workers in factories, they were individual or family artisans working for the cloth dealers, they had to be literate and numerate: Here’s Benedicte – the city guide again.

Its proof that it wasn’t just a group of workers who spend his time to work, but it was people who know how to count, read. And then it’s the proof that it was the excellence of the workers. And you remember, we talk about the silk as a complex weaving and you, you need to know to count, for example, because to prepare you a mechanical loom you must install several thousand of yarn of silk mean it’s, it’s very complex and it’s the proof that it was very clever people, in fact, and not just someone who work all along the day will never think to other things.

Lyon was one of the first places in Europe where labour began to organise and where the workers set up their own sick pay and welfare system for themselves and their families. Lyon was one of the places Karl Marx had in mind when he wrote Das Kapital. There were workers revolts and riots in Lyon to protest at conditions and exploitation by the Silk Traders. Blandine Rauzy – who helps to run one of the only working silk weaving workshops left in Lyon today – explains:

You never knew how much you were paid. So they wanted to create a minimum salary in order to have something to live on. There’s this sense of community because all the weavers were weavers. So they knew how it was difficult to live. And they wanted to have just one voice instead of so many little voices that they have no weight. And just one voice put together, all the weavers put together with one voice is more powerful than many voices.

It was a battle over workers’ rights that was to go on for hundreds of years. But this enterprise and intelligence – this focus on textiles also led to the invention of something extraordinary. In 1801 Joseph Marie Jacquard – born in Lyon – demonstrated the first Jacquard loom in the city. This would not only change the face of Lyon utterly but would also go on to change the world – and is still doing so right up until the present day.

Before the 19th-century complex weavers had drawlooms, which had laborious systems for individually raising sets of shafts, by hand to create the pattern – that meant that every weaver had to employ drawboys to work with him. Joseph Marie Jacquard invented a punch card system instead and installed a Jacquard head with the new punch cards on top of the existing looms. It was a brilliant solution and it’s estimated that it sped up the production of complex silk fabric by a factor of three. Blandine calls the Jacquard mechanism was a kind of brain for weavers.

It’s to replace the human brain. Because before the Jacquard mechanism, all the threads were lifted by hand. So the people who did this type of job had to remember all the sequences of lifting, of the threads and the Jacquard Mechanism was able to replace the human brain. So it’s kind of a mechanical brain. It’s working thanks to the punch cards, which are the beginning of the computer. It’s a binary code in the computer. It’s one and zero here. It’s if there is a hole, that means, yes, the thread is lifted. If there’s only the card, that means no, the thread remains where it is. So thanks to this binary system, we can do all the patterns we want. There’s no limit to imagination.

It changed the face of textile production across the world, and it continues to bring about change in other ways as well, as Blandine says, Monsieur Jacquard’s punch cards were based on a simple binary system, in this case, up or down for weaving shafts. This was adapted by Charles Babbage in Britain later in the 19th century to create the first computer – which leads us step by step from weaving innovations to the digital age in which we now live. But at the start this innovation was hated in Lyon as it put the drawboys out of work, – here’s Blandine again.

So the Jacquard mechanism was not very, very popular, but we saw that it was very useful for production. And also it was quite expensive to put the jacquard mechanism on a traditional loom. That’s why at the beginning, not so much people had, could put a jacquard mechanism on their looms. So it take, it took time to settled all the mechanisms on all the little workshops.

Monsieur Jacquard also changed the face of Lyon as a city too. His jacquard box which fitted on top of the old looms meant that the ceilings of the apartments in which the weavers lived and worked in the old town were too low and the district too cramped. So the weaving community moved stock and barrel to a new suburb of Lyon, high above the river, called La Croix Rousse – the Russet Cross – where new apartment blocks were built to house the looms and their jacquard attachments.

I’m standing in front of one of the workers’ buildings constructed during the early 19th century in La Croix Rousse. It is, like so many others in this district utterly plain – there is no ornament or decoration, there are only high windows, as many as possible in each wall. On the ground floors would have been the silk fabric shops with their small storage mezzanines above them, and then for up to six or seven floors above that the weaver’s apartments, places where they would have lived and worked with their families. Each flat would have housed two to three looms. These buildings are made of huge slabs of stone to hold the weight of so many looms and they filled the spaces between the floors with gravel and sand to absorb some of the vibrations – even so the noise coming from just one of these buildings must have been intense, imagine what street after street of it would have sounded like.

That’s the sound of a Jacquard loom weaving – just one – it makes a special noise which the Lyonnaise called Bistanclaque, a word that has transferred itself to describe the looms themselves. The weavers also created a network of paths through the city, these were essentially private passageways which allowed them to move about the city quickly trundling silk or finished goods – these Traboules as they are called are still there today, open a door that looks like a the front door of a house and suddenly you can find yourself in a warren of covered paths that take you through the city under houses and apartment blocks and lead you out of another door, back into a different public street. Lyon’s fabric production reached its peak in the second half of the 19th century, and after that began to decline, as other centres rose up to take its place and the demand for highly complex woven silk fabrics declined and we moved into a different age of more democratic fashion. The only looms that are working today are looked after by Blandine Rauzy and her colleagues in an apartment that was given to them by one of the last weavers in city. Madame Letournau was a passmenterie or trimmings weaver and left them a magnificent loom that can weave 18 different tiny ribbon warps at the same time. Otherwise, the looms are quiet and the city seems to have moved on:

Lyon today is an enormously prosperous and successful modern city. The Lyonnais quite righty have a huge pride in it. Its textile industry has largely disappeared – there is very little of the weaving skill and savoir-faire that once made Lyon a byword for beautiful silk textiles. And yet – dig a little deeper and you see that even today the city is built on the foundations of textile wealth. The thriving banking sector – including the huge French bank the Credit Lyonnais grew up to finance silk weaving, the modern chemical industry here as the silk dyeing works, the 20th century car production here grew out of the mechanical skills of making and repairing complex jacquard looms and even the food for which Lyon is justly famous is a cuisine developed out of a need to take cheap ingredients – the kind of things you could afford on a silk weavers pay – and turn them into something delicious. So the textiles have gone but they provided the foundations on which this city thrives.

Benedicte Roy – the city guide says that the link with silk is still important

You can take all the activities, all the economical activities. Each time you find a link with the silk. It means for me that if there is no silk activities, now there is no industries, there is no economical development. it’s very important for us.

Benedicte also points out that Lyon does still have a connection with fabric, just not silk. It makes modern textiles such as Kevlar the fireproof fabric, and also seating material for planes and trains. But today in the heart of La Croix Rousse the streets are silent and the old weavers’ apartments are now smart flats for families and young professionals – the only clue to their past is the odd drift of sand or fragments of gravel dropping sometimes from the old ceilings – a ghostly reminder of what once was and how the city’s prosperity and success were built on the sound of thousands of looms creating magical fabrics.

Thanks to Marion Falaise and Suzanne Lasalle at Lyon’s Textile Arts Museum. To Leslie Fonlladosa for valiantly translating, to Benedicte Roy for her passion for her home city of Lyon, to Blandine Rauzy at the Soierie Vivante, and most of all to Stephanie Engelvin at the offices of Go Lyon – who played a big role in making this podcast possible. If you would like to find out more about them or about silk weaving in Lyon, then you can find resources and links at https://hapticandhue.com/tales-of-textiles-series-3/. Thanks too to Bill Taylor of the Lark Rise Partnership who produced this episode, and lastly to all those listeners who helped to make this third series possible by supporting it via the Buy Me a Coffee button on our website. Next time we will be exploring a story of scandal and subterfuge, I’ll leave you with four clues – here they come: the American Civil War, Rhubarb, Smuggling Recycling. Join me next time to hear more, and thanks for listening.