Second Season: Episode #16

A Feeling of Belonging

This episode explores the ultimate textile with a message – a flag. One commentator calls flags a kind of window onto history that can link people across time and anchor them to their communities. In this podcast we look at one particular type of flag, the joyful Asafo flags from Ghana’s coastal region. These are works of art that have a particular history and tell the stories and reflect the culture of the Fante people in a special way. We talk to an Asafo flag maker about his craft, to a collector of these flags and to someone who is helping to breathe new life into the creation of Asafo flags.

If you are interested to find out more about the flags you can find Barbara’s Eyeson’s website at https://www.asafoflags.com/ and a film about the flag makers at https://www.asafoflags.com/film. Barbara has a shop on Etsy where she sells Asafo flags: https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/AsafoFlags?ref=simple-shop-header-name&listing_id=670097492

Gus Casely Hayford’s film about Asafo flags, Stitches Through Time is on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uh2XaqB_pl0

Akwasi Aidoo’s book of poems is called Rhythms of Dignity and it can be seen and/or bought at https://uk.bookshop.org/books/rhythms-of-dignity/9782359261004

To sign up for your own link to the Haptic and Hue podcasts as they are released, for extra information and a chance to access the free textile gifts we offer with each podcast in this series, then please fill out the very brief form at the bottom of the Listen page here. If you are interested in a long read or two or want to know why and how cloth speaks to us then you can find articles at www.hapticandhue.com/read

If you are interested in books on cloth and textiles generally, Elementum which is a small independent shop in Dorset specialising in Nature and Story, has a curated Haptic and Hue list where you can view and purchase a number of books. Excellent for directing If you would like Elementum to post any of these books outside the UK then please contact Jay Amstrong at jay@elementumjournal.com

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Kwame Sasah in his studio

One of Kwame Sasah’s finished ASAFO flags

Peaceful Co-Existence, Kwame Sasah

Barbara Eyeson

Vintage Asafo Flag

Vintage ASAFO Flag

Gus Casely Hayford, Inaugural Director

V&A East, picture from the V&A

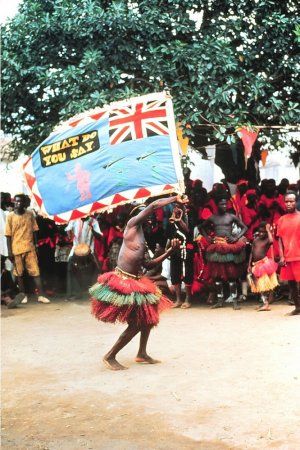

Dancing Asafo Flags in Ghana

Asafo Flags in Ghana at Festival,

Picture Credit: Joy Online

A Feeling of Belonging Script

Textiles are useful: items of purpose to dry the dishes or to cover us while we are asleep. Textiles are beautiful: we wear them to express who we are and how we feel. These are the ways we think of cloth and often we forget that textiles are objects of enormous power. We use them to express our core beliefs, our deepest emotions about our country, our political and religious beliefs, to tell people where and what we belong to, whether it’s our football club, our clan or tribe, our country or just our school or golf club.

I think there is something about cloth that we, in our relationships that we as communities try to draw ourselves together because there is strength in coming together. And so much of that is about shared narrative. It’s about closeness to others and cloth. I think in its very formation of, of warp and weft of weaving. It is about binding things together about a closeness. And about, as you started back, could you get perspective? You then understand how, what seemed like small knots, what seemed like, you know, tiny patterns become something which with perspective take shape in the way that communities, if we understand our, our part as a single individual within them, and that I think is something which makes cloth incredibly powerful, but then also the understanding that binding all of that materiality together, that texture pull, pulling it all together. Is it strength, but it is also its vulnerability, a single knot unravelling could lead to the unravelling of the whole piece.

That’s Gus Casely Hayford – currently Director of the new Victoria and Albert Museum East in London and former Director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington DC. Welcome to the second series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews, a handweaver interested in how all kinds of cloth speaks to us and the impact it has on our lives. Each of the episodes in this series takes an emotion and unravels how we express that in textiles. This episode is about A Feeling of Belonging and it looks at how we express our identity through textiles. Our lives are awash with fabric of meaning to such an extent that I think we have ceased to see the fabric and almost automatically see beyond it to the meaning presented to us. Do we see a piece of cloth when we look at our national flags, probably not? Instead, we think about what it means to be a citizen of our country. Some of the most powerful and dignified images we see are of our dead coming home draped in our national flag. We invest some of our deepest emotional experiences in cloth. Inquiring into how we express our sense of belonging through cloth is a lifetime’s work, and NOT that of a single podcast, or even a series. Imagine the rabbit holes we could go down! Medieval battlefields, clan tartans, gang warfare, football clubs, religious dress and emblems. But I decided we should set off instead for a small joyful corner of this vast topic of belonging.

We are in Ghana, in the coastal province of this West African nation among the Fante people. These people were some of the earliest in West Africa to have contact with European traders for better or for worse – and sometimes it was for a great deal worse. It would have been in the 15 and 16th centuries that British, and Dutch ships, began to arrive regularly on this coast.

Well, that, I guess one of the first things that, that the people of West Africa would have seen of Europeans when they arrived was that their ships coming over the horizon and on the master of their ships would have been flags. You know, flags were the ways in which I guess European nations would have defined themselves. And you know, that that would have been the thing that, that, that West Africans would have seen if them and when Europeans began to make their presence permanent on the West African coast, they built forts and they built trading encampments and they would, they would have small armies that they would have to protect their encampments. And they would fly their flags from the mosque, but they would also kind of seek to make alliances with local people to help to different defend their trading interests. And particularly in the Fante region on the Southern coast of Ghana, that these trading and interests became enormously profitable because of gold, that was being transported off of the coast that was coming from the Santee interior. And so they built a large number of castles and fortified encampments and on the coast, and they forged alliances with the local people who they formed into military companies and these military companies, they were allies of the British.

These Fante military companies collectively became called ASAFO companies, from the local words, Sa meaning war and Fo meaning people.

And the Asafo companies became a formidable force. And one of the ways in which they would rally their troops, their young was around this amazing tradition of flags and flag making. And when a young person reached the age of maturity that they might commission a flag and the flag would be a beautiful thing that would tell stories that in some way reflected the lives or the interests of that family, they may be mottoes. They might be passages from history. They might be depictions of things that people were trying to evoke the spirit of, you know, even that could even be machinery. So in the early 20th century that there are lots of flags with biplanes on them. There are flags with bridges on them, but often they are flags with mythical beasts, or trees or things that from nature. And that in some way that the picture evoked something that was special, that these flags could be flown on special occasions in their earliest manifestation, they would have been taken to war. But more often than not that they were symbols of, of, of families and of individuals and ways of binding people to these very special histories and of pulling and drawing communities together.

For hundreds of years the ASAFO companies have existed and survive today. There are around 15 to 20 companies in different towns on the coast. Each one has its own musicians and its own colours and mottos. In the old days, the flags were formed of a picture, expressing a story, and then in the corner a British or sometimes a Dutch national flag. Modern Asafo flags tend to have Ghana’s own national flag in the corner. These flags are quite different from what we imagine when we think of national or military flags, they have a joy and a fresh artistry to them which make them things of great beauty. Over the years they have become much more than flags of war. Today they are principally used in festivals.

If you imagine in these environments that, that, that life could be incredibly fragile, short for some people and, and challenging for many. And that the ways in which people could celebrate continuity and history was through the sorts of things that simultaneously endured across generations, but also demonstrated a kind of fragility, which became metaphorical. It, you know, that you could see in a flag, this was an old flag that had been repaired and loved over generations that had been flown on many occasions, had become sort of, you know, ragged and, and, you know you could see the threads had been torn over many times of being flown, but it was that relationship between permanence and, and, and fragility that made them special because, you know, that was like the continuity of family and on a special occasion that flags might be flown, but you would also have a flag dancer, someone who would move between, between groups, you know, or special festivals, and they would, they would dance with the flag, using it as a way of drawing people together, uniting them, binding them around these glorious symbols of, of continuity. And in those that it could be that these incredibly fragile, beautiful things that they would, you could see them rippling and tensing in the wind and tiny fragments of them flying out across these crowds to dust the cheeks and the foreheads and the shoulders of the crowds with, with just tiny little desiccated fragments of these beautiful flags. And it was a sense in a way of being touched anointed by history itself, being palpable in these beautiful objects, that of them representing something that was material, but also something that was something more, which was about continuity and, and heritage

ASAFo flags are appliqued and they have a language all of their own. They tell stories and express proverbs and mottos. They are made by men and originally they were made in secret and at night.

And they are, these flags are made by men traditionally. And I think that is about their connection to war. But traditionally in Africans, I guess in, in many parts of the world that many crafts are very highly gendered, that there are parts of Africa in which, you know, most of the potters of women. Many of the people who work in textiles may well be men, you know, that this is something which changes from territory to territory, but in Southern Ghana or the gold coast in the period in which these flags really kind of come into being that they were part of a tradition of war-making or of, of defense of territory. And one of the ways in which a young flag Baker would acquire their skills wasn’t just about learning to, so it was also about learning particular kinds of, of spiritual ways of enhancing the power of the flag. And those were traditions that were held within particular fraternities, particular male, male groups. And so the staff flag tradition, both the making and the flying of them became something which was very male. But one of the ironies is that in this part of Ghana, that the way in which you would inherit things the way in which you would inherit your, your bloodline your property was actually through the maternal line. And that is, again, that sort of connection of bringing together a kind of, of, of a dualism of bringing together seemingly opposing forces and uniting them to create a particular kind of, of power, which is something that is very much part of Southern Ghanaian and also an awful lot of African traditions.

Kwame Sasah is an expert maker of ASAFO flags. He lives in Kormantse in Ghana’s central coastal region. He felt called to do this after visiting one of Ghana’s best-loved National Parks – Kakum, which is in the south. Kwame – speaking to me on a difficult link from Ghana told me that when he got home he was determined to start a new life as a flag maker and he found a flag master really close to his home:

So I went to him and I told him, I want to learn how to make a flag. And he said, okay, I will teach you, or I will let you know how to do it. But then before then, you have to give me an amount of Ghana schnapps and then a chicken. And I said, okay, that is okay. That is how I set out to make the flag.

It took him 6 months to learn how to do it and then a further 6 months before he felt confident. He works not just for one company but for whichever company comes to him and asks for a new flag. Each company has its own colours and wants different stories told in the flag they are commissioning.

For the colour, it depends on which company they are coming from. They would tell you which colors they want, but it will come from what they tell you to do for them. If they want you to do something for them, they will tell you, they will give you the story. And you will come out with the, you know, what to do with it. But the colours, Company number One, you don’t add white, you don’t bring white in one of their flags because Number One Company is black and red. For Number Two Company, you don’t bring it black and red because its colours are white and blue, for number two. For number three companies, or number four companies, they determine what colour it should be. Otherwise you don’t make the colors. If you are from number one, you ask them and they tell you.

Each flag can take up to a month to make. One of Kwame’s favourite flags shows a snail and a tortoise, a man and a broken gun.

It’s easy to pick a tortoise in the forest. Or if it is a snail, you can easily pick it without having to shoot it. So if somebody tells you I want something to do with peaceful coexistence, then you have to come in with the person and the tortoise. I decided that with these two animals in the forest there won’t be any gunshots. This one is easy because you only have to bring in the tortoise. You put in a tortoise and the snail and a gun and it’s a broken gun. So that is how you do your flag, depending on the story,

There are also a lot of flags with sailing ships on, these have a less happy history. They tend to be reminders of the slave trade that was carried on for centuries along this coast. Other pictures show o whales as the big powerful beast of the sea and much admired by these fishing communities, Turtles which mean moving in silence, eagles that express power and control, and lions with castles. Each flag represents the flag maker’s personal representation of the message or proverb. Kwame regrets that more younger men aren’t taking up flag making and he is concerned that this tradition will have no future unless a conscious effort is made to save it. An incredible piece of Ghana’s history and culture is in danger of being lost if the makers aren’t replaced.

It has been part of our culture and it is a very powerful way of communicating with the other communities in the olden days, we didn’t have a military as such, but what we had is the ASAFO companies, like a paramilitary and that is what was used when going to war, or it’s also a question of when people die, if you are a member of the company, you use it, It’s a way of communicating with each other. So to me, it’s a very powerful thing and it’s very beautiful.

But one of the interesting things about ASAFO flags seems to be that while they may be in danger of falling into history amongst the Fante people themselves, outside Ghana they are now going through another transformation. The Ghanaian diaspora and the African diaspora more generally, value them as art. Here’s Barbara Eyeson, who lives in London. She sells ASAFO flags and also works with makers in Ghana to create new flags to sell to an international audience.

Oh the reaction is always a wow, that’s the first thing reactions always. And then they do their research because they want to know what this colourful flag is. And then they come back and as I say, wow, I’d really like one the Etsy shop is more sort of affordable. And the majority of people that sort of buy them are, I’d say interior designers, collectors as well. Some, people just want to collect them just for the history of it. I ship all around the world. So America, Japan. The interest sort of varies, but a lot of the people that collect are mainly people that are also interested in art as well. I think a lot of people want new artwork in their homes and it wants something that’s quite meaningful. Also what a statement piece. So it’s a unique sort of appliqued art that people want. So yeah, it is a variety of different people.

Barbara says that there are ASAFO flags in the collections of the Smithsonian, the British Museum and in Canadian Museums, the price of the older vintage flags has rocketed

So some of them sort of run into the thousands cause they’re quite rare now. So I’m working with the flag makers now to make new ones, as opposed to just, you know, everybody scrambling for the old ones. I’m sort of working with the flag makers that are currently there to produce new ones. I don’t know, for some reason, I think it’s, it’s probably gonna come back in a different way, not so much in a sort of traditional way, but it will be more represented and respected sort of outside of Ghana. A lot of people know about it more outside of Ghana, which is a bit of a shame, but you know, we’re trying to sort of change that.

She travels to Ghana regularly and talks to a variety of flag makers. Her work is not just about selling flags, but also about championing the makers as artists. She believes that awareness of the ASAFO flags is spreading:

Good question. Well I think now because most of the flag makers are of age, so most of them are sort of sickle two of, two of them are sort of like 60 plus there’s only one that’s quite young. That’s doing a, who is a grandson of a prominent flag maker. I think the awareness has been pretty amazing. So there’s a lot of people that are sort of supporting and are interested in the flags, whether it be vintage or new. But currently, now I’m sort of working on producing new flags for the collector as they are replacing the old ones. New flags are now coming to the market, but working directly with the flag week is not, you know, sort of purchasing a tourist site or be good to sort of work directly with them to produce new flags with new designs.

She also says that traditions in Ghana are changing and that women are beginning to find a role in making ASAFO flags.

Okay. So quite interesting. It was quite interesting when I met a flag maker back in March this year, actually, and the wife was there, the wife was helping out the husband with the work. They do get involved, but they don’t make a whole flag by themselves they sort of help out with the materials, the measurements or cutting. Another flag maker did say that a woman actually does it by herself. I haven’t met her yet, but I’m hoping to be home soon!

Over time Barbara has made links with a number of flag makers. Her work means that even though she is encouraging the flag makers to come up with new designs, and she is selling the work internationally, the flags remain deeply connected to the context in which they were first created. Barbara’s interest comes out of her own knowledge and her heritage:

I’ve always been interested in old things. So all textiles arts, old vintage photos and postcards, I’ve been collecting them for a number of years. And I actually came across a flag on a trip to Ghana about 10 years ago with family. And I was intrigued by sort of the odd-looking Union flag, because some of them have different types of union Jack designed on a corner. This one was quite odd-looking. So I was like, okay, this is a bit, it’s a bit weird. Cause I didn’t really look into the history of Ghana beforehand. Some of them had different sorts of flags, like the St George’s Cross. And then some of them had a Dutch flag on them. So when I got back to the UK, I did more research into the textile and even so more into my heritage.

It was the same story for Gus Casey Hayford who grew up as a London boy.

My father was Ghanaian and then my mother’s Sierra Leonean, but we grew up in South London and Africa in my youth, it seemed like a million miles away, you know, not like another part of the world, but almost a sort of an impossible dream, the sort of place of fiction. And, so as soon as I was able when in my late teens I traveled and I wanted to see this place, that my parents had talked about, that my aunts, who, when they came to visit wearing gorgeous cloth and with amazing baskets, full of delicious fruit and foods that I’d never experienced or could never buy in London at that time. And they also came with amazing stories and these stories were so often they were illustrated by pieces of cloth, that they would spend these gorgeous narratives about West Africa, through cloth and through their use and through their histories. And I wanted to see this place.

If Gus’ aunties achieved nothing else, they sparked a curiosity in him to explore this heritage. As soon as he was able he took himself off on a shoestring to West Africa.

And on my very first trip to Ghana, that I went to a place called Cape coast, which is the coast as the name would suggest, but in a region, which is a fantasy. And the Fante are one of the smaller ethnic groups, within Ghana, but they have a very, very expressive material culture. And one of the ways in which they are extremely good at telling their stories is through cloth, particularly flags. And it was there that I first saw one of these Asafo flags, which was shown to me by an old uncle who sort of unraveled one of these cloths, taking it out of a drawer, and then began to weave these incredible stories around and through the narrative of this incredible place of cloth. And it was this sense of understanding how cloth, it’s not just an object that had a utility, but it could be a kind of window onto history, a sort of window onto all kinds of narrative possibilities that could link people to place across time to mythologies, that it could be an anchor for communities that might tie them to, you know, to great myths or stories that were fantastical, but it was always a way of drawing people together. And it was something that absolutely got into my blood.

Gus now has his own small collection of Asafo flags. And because of his role as a museum director, he is also in a position to influence the way in which they are seen and valued in the wider international community. There is no doubt that in Ghana they are in danger of becoming a remnant of history as the flag makers themselves age and are not replaced. But there is a new real sense of energy and purpose that is just beginning to flow back into the making of Asafo flags. This time it is not coming from inside Ghana but from the diaspora who value these beautiful flags and are spreading the word of their existence and history. I find it a wonderful example of how textiles change through time. How different cultures alter the way they are used and made, fitting the needs of each succeeding generation. These flags began life as ship’s flags on European ships, they were then re-purposed as extraordinary ASAFO flags, expressing the heart of what it meant to be from Ghana’s coastal communities and now they are changing again into art and decoration for a new generation who value the skills and stories behind these flags as emblems of African identity. Gus say they are glorious things to live with, although he believes there is no substitute for seeing them on their home ground.

When you see a flag, there is something special about the visual language. There is something particular about when you see them flying about the way in which they work together. And particularly against those amazing settings, these coastlines are incredibly geographically dramatic. And you understand how this is a tradition, which is not just about a graphic understanding of something, but it is far more kind of intellectually resonant, which casts these flags, I think for me, into the realms of, of great art, rather than just something that could be considered to be a trade that you would pass down, that you would just learn one generation over another, but you could replicate by copying. This is something in which there is huge invention, huge thought, and consideration and imagination, and the great flag makers produce things that are on a par with the great art of any continent. So if you get the chance to see them, they are glorious things, but if you get the chance to see them flying, to see them being actually danced with, with drums it is, it’s a sight to behold. And I would imagine if you’re impacted in the way that I was on the very first time that I saw one of these, it will be something that you won’t forget

Thanks to one of Ghana’s dwindling band of Master Asafo Flagmakers, Kwame Sasah, to Gus Casely Hayford, and to Barbara Eyeson for sharing their own stories of how ASAFO flags came into their lives. I’ve posted some pictures of ASAFO flags on the website, and of Kwame creating them in his studio. You can find them at www.hapticandhue.com/listen, where you will also find a full script of this podcast and a form that gives you a chance to win the textile-related gifts I give away with each episode. If you want to see more Barbara also has some vintage flags in her Etsy shop, which is called simply Asafo Flags.

Before I go I wanted to thank all of you who have bought me a coffee. The response to this slightly hesitant request has been tremendous. I am extremely grateful. The funds- more than £450 – will be used to meet the costs of getting the next series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles on air in the autumn. I hope you all will feel it is worth it! There is however one more episode to go in this series. In that, we will be thinking about a Feeling of Nostalgia, how textiles hold memories, and how the sight of them years later can bring back long-forgotten feelings. I will leave you this time with work from a man who I am delighted to call a friend. The Ghanaian poet Akwasi Aidoo has just published his first collection of poetry, called Rhythms of Dignity. Here he reads one of his works from that book – called Query, which is about Africa.

Query:

We are a developing country you say?

That we need

Time to mature?

Unity to develop?

Discipline to comete?

Hmmmm…..when we have

Time

Unity &

Discipline

And before we

Mature

Develop

and

Compete

Can we

Dance?

Dream?

and

Struggle?

Can we resist your

folly?

With justice?

Can we?