Episode #51

Jo Andrews

Today feed sacks are valued by collectors and makers in America and beyond, and there is a lively global market in them. But these soft cotton sacks have a much wider story to tell us than that. They have played a role in creating one of the world’s legendary cricket teams, they have saved a nation from the brink of starvation and in this episode of Haptic & Hue, we also tell the incredible story of how a flour sack re-united a family with something created by the grandmother they lost in the Holocaust.

Notes:

The music used in this episode is used under licence from Pond 5. It includes:

- This Land is Your Land by Woody Guthrie

- Delta Chain Gang – Old Time Delta Blues

- Belgian National Anthem: La Brabançonne

The people you hear in this episode are:

Linzee Kull McCray: she is on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/seamswrite/ and her website is at https://linzeekullmccray.com/

Her book is called: Feedsacks: The Colourful History of a Frugal Fabric.

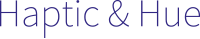

Sarah Walcott and Jamie Swartz are at the International Quilt Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska, USA. The Quilt Museum is on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/internationalquiltmuseum/. The exhibition called Feedsacks: An American Fairy Tale is on until July 27th 2024. You can find out more on their website at https://www.internationalquiltmuseum.org/exhibition/feed-sacks-american-fairy-tale

Rose Sinclair is on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/dorcasstories/

Annelien van Kempen is on Instagram as https://www.instagram.com/floursacksww1/ you can see a number of flour sacks there.

Her blog can be found in Dutch, French and English at https://meelzak.annelienvankempen.nl/

Her blog on Nelly Sassenrath is at https://meelzak.annelienvankempen.nl/tag/nelly-sasserath/

Linzee Kull McCray

Floral Feed Sack Fabrics. Photo courtesy of Linzee Kull McCray

Patterned Feed Sacks. Photo courtesy of Linzee Kull McCray

Jamie Swartz

Sarah Walcott

Stack of Colourful Feed Sacks. Photo courtesy of Linzee Kull McCray

Flag Quilt made c 1920 in Nashville, Tennessee, by Sarah Dorthula Hooper Taylor.

A Variety of Feedsacks in the IQM’s Exhbition

Mid Century Clothing Made from Flour Sacks, in the IQM Exhibition

Rella Thompson’s Quilt, Franklin County, North Carolina, United States, c.1935.

Quilt by Geneva Thomspon Alston, Franklin County, North Carolina, United States, c 1960-1970.

Rose Sinclair

Annelien van Kempen

Belgian Children in Dresses Made From American Flour Sacks c 1915

Belgain Girls Embroidering American Flour Sacks

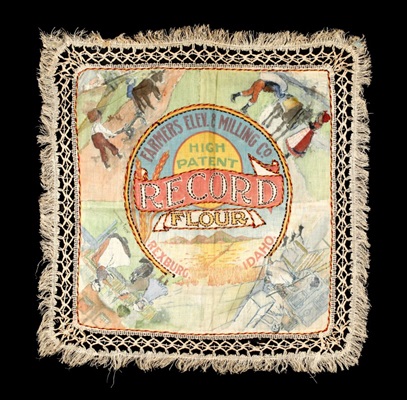

Nelly Sasserath’s Embroidered and Painted Tablecloth (picture Annelien van Kempen)

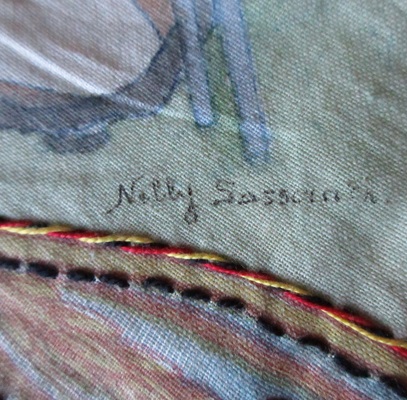

Nelly Sasserath’s Signature (picture from Annelien van Kempen)

Betty and Claudine, Nelly’s Daughters, After the War (Picture from Annelien van Kempen)

Script

America’s Cotton Feed Sacks: And How They Changed The World

JA: The cotton feed sack is a humble thing. I have one given to me by a listener. It dates from the middle of the 20th century and it’s an oblong of soft plain weave fabric with a small blue and brown flowered print. It is lock stitched up one side and at the bottom so that it can be opened out and used as a single piece. It’s extraordinary to think that this simple piece of fabric has had such an impact on so many people around the world:

Jamie: Feed sacks embody an important facet of the American dream where people, lift themselves up by their bootstraps and make do and mend and use and reuse and have us a sense of thriftiness in them.

Rose: In the Caribbean, flour is like a kind of all-consuming material that’s used for cakes, for bakes, for cocoa breads or whatever. It’s the dough for your patties. And so the fabric that’s then results from it is also a precious piece of fabric. You’re not going to throw it in the bin.

Annelien: The flour sacks with the logos were so exotic for the Belgian people when they arrived in the bakeries. It was also a kind of pride and also a patriotic thing against the Germans, the German occupiers. So when the bakers emptied each flour sacks, they presented the empty flour sack in their windows to show that they had American flour. And people were so excited by these sacks that apparently, they asked, okay, may we use these sacks?

JA: Welcome to this episode of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles, I’m Jo Andrews, a handweaver interested in the stories textiles tell us, and the often hidden hands that fashion cloth into something useful and beautiful. These tales almost always have something new to tell us about ourselves and cast a fresh light on our families and communities.

The feed sack has travelled far and wide and while it has unquestionably brightened millions of peoples’ lives – even saving some from starvation – it also has its dark side. It was born out of America’s cheap cotton crop which was grown and harvested on the back of enslaved peoples and then poorly paid and exploited sharecroppers.

Linzee: Well feed sacks or cotton sacks started in the mid 1800s, I think it was 1847 when Elias Howe patented the sewing machine, the lock stitch sewing machine. And that allowed bags to be held tightly shut in a way that they hadn’t before. And that coincided with a plethora of cotton in the United States, which in large part was due to slavery because we had all of this cheap labour. I’m, I’m doing air quotes on cheap labour. You know, that, that so much cotton was being grown and produced. So, this combined, and that was the beginning of the, the sack era.

JA: That’s Linzee Kull MCray who has written the classic book Feedsacks – The Colourful History of a Frugal Fabric. Linzee says that before the sacks appeared goods were moved around in heavy and awkward wooden barrels and boxes. The sacks were much lighter but they also had an unexpected impact:

Linzee: These sacks were largely just plain sacks. Sometimes they would have the, the logo stamped on them from the mill or whatever. But as soon as that happened, people started using the fabric, I mean, right away., fabric was something that cost money. And if you were a rural person, or a city person and didn’t have much money, this was like free fabric. And it didn’t take manufacturers long to figure that out. And then as time went on, they started trying to make their sacks more and more desirable. So, they, you know, would print embroidery patterns on them and they would print instructions on sew these four together to make a bedsheet or a tablecloth, or instructions on how to get the ink out from the, the label that was printed on the sack.

JA: And people began using the plain sacks for lots of things.

Linzee: And in Dearborn Historical Museum in Dearborn, Michigan has a wedding quilt, hand pieced in 1850. And the top contains more than a thousand pieces of fabric, and the back is sacks. The back is sacks. And that was a common thing that, you know, if you had a logo that was hard to get out of a white piece of fabric, you would use it where it wasn’t gonna show like the back of a quilt or the underwear was very common, You would use it in your undergarments because then you didn’t have to worry about getting the label out, so, and there’s the apocryphal story of the woman who was making undergarments for her husband. And she didn’t bother to remove the label from the flour sack that said, self-rising. You know.

JA: In America in the 1930s as The Depression took hold the flour millers started printing fashionable patterns onto the feed sacks:

Linzee: Manufacturers realized that these women, many of them rural farm women were not, maybe the people who were going into town and making the actual purchases. They were not the person who had the pay, the pay check, or the money in hand, but they very clearly drove the decision making. You know, I interviewed many, many people who told me stories about their mother or their grandmother sending them, sending the father or the son into town with a swatch of fabric and saying, get me two more sacks that looked like this, so that they had enough to make a garment or whatever they needed. So yes, women were very clearly driving the market for this. And the goal, I think, was to make the sacks almost as valuable as what was inside of them.

JA: This was one of the first marketing campaigns in America directed at women – and it worked:

Linzee: Yes, it was very successful. In, sometime in mid 1940s, there was something like more than 3 million people in the United States wearing clothing made from feed sacks. People used feed sacks, the fabric from feeds sacks for absolutely everything. One of the women that I gave a talk at my aunt’s retirement community, and she told me a story, which I thought was really a good example of feed sacks. She said her mother would make the girls dresses, and then as they would outgrow them, of course, they would pass them down to the younger daughter and the younger daughter. And then when they got to the point where no one else could wear them, she would take the fabric from them and make pyjamas. And then when those started to get worn out, she would take the fabric and that was still good and make aprons. And when that got worn out, she would make dish towels and then that fabric would wind up in the barn as a rag.

JA: No part of a sack, however trivial, was wasted:

Linzee: And in some homes, every bit of cloth was once a sack. Another interesting aspect of that is that people saved the string too. The string that held the sack together, people saved the string. And one woman that I interviewed told me stories about on her farm where she grew up, there was always a ball of string. And that string got used for tying up plants, for tying up packages, for mending her father’s overalls. You know, it was kind of a thick, thicker than a regular thread. So yeah, the, even the string was saved. And I’ve seen doilies that were made out of the string crocheted from the string. And one woman in Texas told me a story that her mother knit socks out of feed sack string, which I can’t figure out how they, they stayed up, but <laugh> with string.

JA: But in the 1930s and 40s the big draw were the prints. Over the years more than 18,000 different designs were used by the flour and feed sack companies.

Linzee: <Affirmative> Well, it was very important for the, the sack prints to be fashionable. I did have some wonderful stories about girls who got to go into town with their dad and pick out the fabric for their dress in the feed store, and these stories of them hopping from sack to stack of these big stacks of them and choosing their own fabric. So, some people certainly did get to pick their own fabric, but the, the prints, they wanted them to be stylish. They wanted them to be fashionable. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find out who these amazing designers were. And one of the things that has happened with many of the records of these companies is, the companies would be bought by one other company and then by another company, and the records were thrown away or lost. Sometimes someone will refer to a woman who designed the fabric with no name. And the only name that I had been able to find was someone named Charles Barton. And he was a European trained New York designer who was hired by one of the fabric companies or the bag companies to bring glamour to feed sacks. And there are stories that he came to the Midwest and drove around and saw what people were doing and wearing and got ideas for his designs. But other than him, I have never found a named designer, very sadly.

JA: Linzee thinks what made the feed sacks so successful in America was the mindset of the times.

Linzee: I guess I would go back again to that, that waste not want not use every last bit, it was just a matter of survival. For many people. It was like, if you wanted to have a diaper for your child, this is where you got the fabric. If you wanted a dress, this is where you got the fabric. And you know, all those little scraps that got left over from the dresses would sometimes be made into quilts or other things. And there was just no waste

JA: There is an exhibition on at the moment at the International Quilt Museum in Nebraska in the American Midwest called Feed Sacks: An American Fairy Tale. Its co-curated by Sarah Walcott and Jamie Swartz:

Jamie: <Laugh>. Yeah, it was intentional, the choice of our like subtitle. It was, a slight provocation to kinda get people in a different frame of mind to kind of have them wonder why we use this subtitle. A lot of the research around it characterizes the manufacturers of these feed sack bags or cloth commodity bags as benevolent, bestowing beautiful printed fabrics upon all these poor rural people for their reuse. And a lot of the time people treated the marketing of feed sacks as sort of a gospel in a way, not kind of questioning the motives behind the manufacturers. And you know, cotton that was grown for the feed sacks, was largely produced by poor people and African Americans in the South. And that sort of facet of the history of feed sacks is largely undiscussed or not discussed at all. And people often think of feed sacks as being like purely American phenomenon when their use and reuse was global.

Sarah: I guess sort of spinning off the last thing Jamie said., and I think our research kind of bore out this idea that feeds sacks are one of these kind of points of myth in American culture around quilt making and textiles. A lot of Americans tend to see quilts and quilt making as the very American phenomenon when obviously we borrowed it like everybody else, <laugh>. And the roots go back thousands of years further and you know, in India, in the Middle East and elsewhere. But I think part of the fairy tale is, like Jamie was saying, that feed sacks and repurposing feed sacks in order to create clothing, quilts or other objects is some kind of product of like American thriftiness and ingenuity. It’s, it’s really not <laugh>. And I think that those myths are really interesting. I think why we want to believe in them is interesting, but I think we can’t really get to the heart of that until we understand what the actual facts of the production and use were.

JA: For Jamie and Sarah the story of feed sacks is much more complex than just the accepted mythology, and one of the ways the exhibition seeks to add layers to the tale is to include quilts made by the people who harvested the cotton:

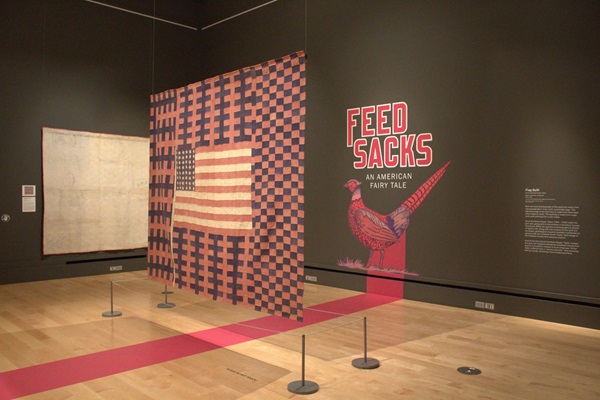

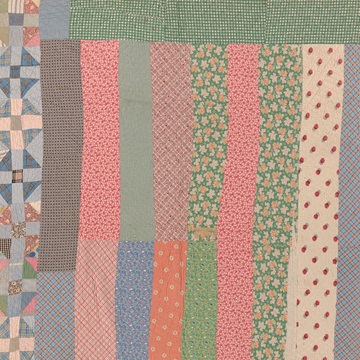

Sarah: And the first, the older of the quilts was made by Rella Thompson, who was born in 1887 to formerly enslaved parents in North Carolina. She lived and worked as a sharecropper and she would trade eggs and produce in order to be able to purchase thread, fabric, things like that, for creating quilts and other items for her household. And so on the quilt that we have, that she created, you can still see part of a paper label affixed to one of the feed sacks. There’s also a pretty thick cotton thread used to do the quilting, and so we think there’s a good chance that was the thread that originally held the bag closed. And the other quilt is by her oldest daughter, Geneva, who was the oldest of her five children. And Geneva’s quilt features over dyed feed sacks on the back. So, the print is still faintly visible but she over dyed all of them in a really lovely blue. So, we were really happy to feature these because it really shows that not only were feed sacks used for through generations, but also quilt making is something that was passed down, was a tradition among families, who have been historically left out of that kind of quilting narrative.

JA Jamie says that the feed sack era also covers a period of rapid change as rural families move into the cities.

Jamie: Agricultural production in America shifted so rapidly throughout the 20th century and we saw the evaporation of the family farm as a means for people to, you know, gain money for employment for also like people were making, trying to make a living on the family farm. And it was becoming increasingly hard with the rapid industrialization of agriculture. That’s another important facet too, I think.

JA: The exhibition has a range of items made with feed sacks from trivets to boxer shorts – dresses to dolls clothes, but as ever it is the quilts that have the best stories:

Jamie: I would say my favourite piece is gonna be the first piece you see when you enter the gallery. It is a quilt that we’ve called the Flag quilt. I’m not sure if the maker called it that we don’t know, but we know who made it. And her name is Sarah Doula Cooper Taylor. She lived her life in Tennessee. She made the quilt about 1920, and it’s made entirely a repurposed fabric. The front side is made of small cotton sacks that were used to house tobacco, even tobacco was sold in little cotton sacks and she dyed them hand dyed them all. And she made this in incredibly beautiful quilt that is an American flag, waving on a pole in this kind of checkerboard background that’s blue and pinkish red. The backside of the quilt is entirely made out of sugar sacks. It said that she dyed the, the thread that she used to quilt it with she had she dye it to match the front patchwork. So, it’s either dyed red or blue or kept white. And, her life, we know a little bit about her through genealogical research And she was born into sort of prominent family, or father was a judge. She married a guy who ended up, for whatever reason going insane and entered an asylum. He committed suicide by drowning in a river that was up near the insane asylum. There was a really dark story, a newsprint article that appeared at the time of his death where it said people at the asylum tried to raise his body from the river through the use of dynamite, which was something I had never encountered, never heard never heard of somebody doing this. They ended up finally dredging his body up near the banks of the river and she gave some of her children up to an orphanage and got them back at some point. Throughout all these life events, she made this quilt that is a symbol of America. That’s why we chose it as the, first piece you see when you come into the gallery just because it embodies, the story of America. life is hard but through it all she’s still like created this quilt and it’s just so cool. So that’s why it’s my favourite piece. <Laugh>.

JA: Sarah thinks that the way in which the feed sacks were promoted has echoes for us today in the age of fast fashion, and that the marketing of feed sacks was one of the first efforts to promote over-consumption.

Sarah: Yes, exactly. I think there’s a lot of great things about, of course, all the, the creativity and the frugality of the reuse. But I also think there was, there were huge pushes in advertising as well as even from the United States government encouraging people to buy and reuse these sacks. During World War Two, feed sacks were classified as an industrial use. So the Government really wanted people to be buying and using them in order to make clothing rather than purchasing ready to wear clothing or trying to purchase yardage when there were shortages of those. And so, I think between manufacturing and a big government push to encourage people to buy, buy, buy, use, use, use <laugh> I think it really, yeah, it really does boil down to capitalism like most things.

JA: The Quilt Museum’s exhibition has a number of items from outside the US: from India, Pakistan and Japan. But the place where flour sacks have a culture and a mythology all of their own is in the Caribbean. Flour is a vital part of Caribbean cooking. Here’s Rose Sinclair who is a lecturer at Goldsmith’s University, in London, and an expert on the histories and craft practices of Black Caribbean women.

Rose: Flour is used for key things. Like if you want to make your soup, you make spinners. spinners are like a fine kind of finger dough that you make to put into your soup. Or they make them for their fried dumplings or their fritters, it’s the food thing that you go to. So it’s your hard dough bread, it’s your bun, it’s your whatever the, the foods that you have., it’s something that’s used every day.

JA: And with flour, came flour sacks – these were plain cotton with blue millers’ brand names on them from America and Canada. It took a great deal of work to get these logos out.

Rose: My mum said it was the soap plant. So, there’s a plant called a soap plant, but she didn’t tell me what the Jamaican name was. She just called it a soap plant. And, you kind of rub it onto the cloth and it creates a soap lather. And then they bash it and wash it on the rocks. So, they would wash it in the river. Or, if you’re at home, you would wash it on like on a ridged board: And you would wash it, rinse it, wash it, rinse it. the soap would actually let that blue stain come out or the dye come out. And once you’ve done that, you would then use what they call the blue, which is like a little pot of dye. But it has a whitening agent in it. And it kind of enhances the, the white. And then you hang it up. And because the sun’s so hot out there, it bleaches, So, they come out ultra-white.

JA: And after all that work the sacks could be sewn into garments, shorts, skirts, short pants, bloomers, and of course, this being the Caribbean – cricket whites:

“If you were watching a cricket game and your eyes were good, you would often spot a small speck of blue, as large as a comma or a period, on a player’s shirt. And you would immediately recognise that the shirt was made from a flour bag. All that bleaching and blueing and the rays of the hot sun failed to obliterate all the letters. That spot, that lingering fraction, perhaps part of the letter C, in the word Canada, would be all it took to stamp this young, ambitious cricketer with the poorness of his social origins……Blame would rest at the door and in the washtub of the poor cricketer’s mother, and the cricketer would suffer the teasing and the many reminders of class and poverty for years and years afterward, until he was welcomed into his grave: “Boy you are wearing flour bag!”

JA: That’s from Austin Clarke’s Barbadian Memoir: Pig Tails ‘N Breadfruit, written after the legendary West Indian cricket team, captained by Clive Lloyd, stormed the world. It intrigues me that some of them may have begun their illustrious careers in cricket whites made of feed sacks, because it is clearly shameful to be dressed in flour bags.

Rose: Yeah It is. Because the element of shame was thrown back at the woman because, she hadn’t been able to wash out the blue dye. So is that because she didn’t know how, or that knowledge hadn’t been passed to her or she just missed that spot, that’s the bit that makes me laugh. Why is it thrown back on the woman? And this is about passing on intergenerational knowledge. And I think if people ever read that piece of Austin Clark’s work, what they see is that legacy that’s been going on for 300 years that kind of work Because they don’t grow wheat in Barbados or in any of those Caribbean islands. That knowledge came out of necessity. So, he’s going by what his mum was doing, but his grandma would’ve done that. His great grandma would’ve done that. So that, that’s learned knowledge that he’s, he’s then passing on to his literature.

JA: Rose has also found evidence that flour sacks were used to make demob suits for Caribbean soldiers that had served in the British army during World War One.

Rose: Well, there were no jobs, but, they needed outfits and stuff. what I’ve found so far is that men were given rations and one of their rations was flour sack fabric to make de-mob suits. I think what would’ve happened, they would’ve either got fabric from either the Americas or Canada and had that imported into the islands. That would be the only way they could make the suits out of flours sacks, or there would’ve been surplus flour sacks on the islands. From the pictures that I saw, I don’t think they were dyed or bleached. I think they were just left plain. Because you’ve got to remember, we’re in a hot country, so you don’t need to dye or bleach it. I don’t think there was any printing on them. So, I think they might’ve acquired the fabric before it got printed. But it does say their de-mob suits were flour sacks.

JA: For Rose, flour sacks and the way they were used, is about so much more than make do and mend. It’s about the knowledge and the skill women in the Caribbean passed down the generations, and it’s about the craft and the know how that help them and their families live with dignity:

Rose: These were valued pieces of fabric that meant that you could go out in your Sunday best. That meant that you could embroider the best pieces of designs on them. And they were saluted when they were on display at the farmer’s fairs. So, this tells us that this cloth had value, it was regarded as high status, as a piece of craft.

JA: And Rose says if anyone has any of this buried in their trunk in the UK or in the Caribbean, she’d love to see it, and she’s not the only one. In London one of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s new acquisitions is a set of beautifully made table mats. A gift to a Windrush generation migrant. Turn them over and put them together they spell out the words Flour, Bleached, Hard Wheat, Buffalo, New York. Once, those words spelt the difference between starvation and survival. Flour and the sacks they came in played an extraordinary role in saving the Belgians from famine in the First World War. This is a tale of American and Canadian generosity that had unexpected consequences.

Annelien: Well, there, there was a rich harvest in 1914, summer, 1914 in North America, and it was usual to bring the grains from North America, to Europe. Europe would didn’t grow their own crop anymore.

JA: Annelien van Kempen has made the story of the flour sacks that were sent to Belgium her life’s work.

Annelien: When the war broke out, there was around the world a lot of concern about the situation in Belgium. Belgium was occupied by the German army, and very soon, because they were used to import their flour, or no, their grains, I must say, because they were grind it in Belgium. But there was a shortage within two, three months. There were no imports available anymore.

JA: And that’s because the British were blockading the big ports to try to stop the Germans supplying their army and people with weapons and food. In London, Britain, which had no wish to see the Belgians starve, agreed that the independent International Commission for Relief could transport American and Canadian flour to Belgium, and the Germans agreed that it could be distributed – overseen by the Americans – which was at that stage still a neutral nation.

Annelien: Now in the meantime, because of the war United States as in Canada, as in Australia, as in Britain, as in everywhere, the people, the population really wanted to help the country that was in need. And it was Belgium. Now, in the United States, there were a lot of Belgian immigrants, and their roots were from Belgium. So, they started their collection of money, but also of products and, and said, okay let’s send these to Belgium to help our people.

JA: Until then flour had come into Europe as grain, to be ground locally. But, because it was so urgent at this stage there was a change and it was decided to send flour already milled in flour sacks.

Annelien: There were three reasons. First of all, the cotton industry in the United States was under pressure. they really needed help. So cotton was a good thing for America to export. Secondly, it would be handy to have them in a 49 pound sacks, which would enable the people to carry them. And then third, they were already aware of the fact that the cotton could be used to, or reused, I must say, to make clothes of it, and in fact, they also marketed the idea of the use of cotton sacks and said, well, let’s do these cotton sacks, because three reasons we help our in own industry it’s handy for the people there. And thirdly, they can reuse because we don’t need these sacks back to the United States, which of course was even thinking about it, a ridiculous idea that you could, in wartime, <laugh> sent back these flour sacks.

JA: So one of the great American fund raising drives of the 20th century began in the autumn of 1914:

Annelien: if every village, every church, every school was involved, for example, in Kansas, in Minnesota, in Ohio they collected money to buy flour from the local mill.

JA: Mills across America and in Canada charged ‘friendly’ prices for their flour and they stamped each bag with their own logo and different texts, like Colorado’s Flour Donation to Belgian Non-Combatants. Or: From Pawnee County Donated to Belgian Sufferers.

Annelien: From the end of November, the railways accepted these, this flour transportation for free. So that was the reason that all the States in the United States were encouraged to immediately send their flour in a very short time. And after the 20 December in fact, the flour was in the ports and from then transported by ships to Rotterdam.

JA: And the impact was extraordinary – this really did save the Belgians from hunger, and it also gave them hope.

Annelien: And imagine that you are in an occupied country having no food, and then comes in these flour sacks and flour. I mean, that looks the same wherever it comes from. But here come in, the packaging, and packaging can be decorated already with prints. So it, it was colourful prints. It, it was with maybe one or two colours, but somewhere really with three or full colour.

JA: The Belgians used the flour sacks for children’s dresses and table runners, underwear, sheets and pillowcases, just as the senders imagined they would. But what they also did was to embroider the sacks, often incorporating the logos into their designs as a way of saying thank you to the generous Americans and Canadians who had rescued them from the brink of starvation:

Annelien: And many Belgians thought, okay, we will embellish these flour sacks. But they also wrote letters, postcards, etcetera. And they donated all this and brought it to the Minister, the American Minister in Brussels. he had to organize, all these gifts into his, his residence. And we know from representatives who travelled back to see their family in, in May, June July, 1915, they took some presents that they received back to the United States. And then of course, to show the Americans what, how well they had done with the charity that they did to send flour in, in the cotton sacks to Belgium. They wanted also in the papers to, to, in the newspapers to show how grateful the Belgians were for this help.

JA: The quality of work on many of these sacks in very beautiful. Several hundred of them expressing thanks to the American people are held in the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library Museum in West Branch, Iowa. Others are still in Belgium. The vast majority of them are unsigned. No-one now knows who made them. But Annelien has been able to find a number that do have names on them, and one of them from Liege was signed NELLY SASSERATH:

Annelien: Nelly was 15 or 16 years old. She lived with her father and her sister, and she had a step mother. Nelly painted a very nice kind of little story on the flower sack, and she also embroidered it. But really, she did a very nice actual painting.

JA: Nelly, was the daughter of a dentist in Liege, and on her flour sack she painted and embroidered scenes of how wheat is grown and milled – so how she imagined the flour reached Belgium. After the First World War, Nelly married and had three children. But the 20th century had more horrors in store for her, because Nelly and her family were Jewish. She and her children went into hiding at the start of World War 2 but horrifically they were betrayed and sent to Auschwitz. Nelly was killed there, but her daughters, Betty and Claudine amazingly survived.

Annelien: So by knowing that there had been two daughters surviving, Hubert and I were thinking, Did these girls marry and have children themselves? Are they still alive? And we found, finally found the granddaughter of Nelly Sasserath living in the United States. And that was such a, such a touching story, to be connected with someone who in fact didn’t know anything about this flour sack. But we were able to get it all together because of the flour sack. And that’s because the educational collection in the museum, is there. This ordinary flour sack, what, what stories they, they still tell to us about wartime and very sad circumstances.

JA: What was the reaction of Nelly’s grandchild when you told them this?

Annelien: A complete shock. It was a complete shock.

JA: Did they, did they know about their grandmother?

Annelien: They knew about their grandmother. Oh, yes. Yes. then you come into the, the whole history of the Jewish people and, and Jewish families. And it’s, that is such a fragile, and, I really was overwhelmed myself by going from this educational collection of flour sacks in the Liege museum to, the, yeah horrifying story of the Jewish people in the Second World War, for every, everyone there, it’s still so precious.

JA So Annelien’s work did enable Nelly’s Grandchildren to be in touch with something that had been made by their Grandmother all those years ago – her work, painted and embroidered onto a flour sack – the last part of her that survives.

Thank you to everyone who took part in this podcast, without their knowledge, research and interest in the story of feed sacks and how they have changed the world, this episode could not have come into being. A special thanks to Glenn Charles for voicing the extract from Austin Clarke’s Pig Tails and Bread Fruit.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me, Jo Andrews, and edited and produced by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund us via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you something extra every month with a separate podcast called Travels with Textiles, hosted by Bill Taylor and me, where we cover a whole range of different textile news and topics. You can find out more about this episode, and see pictures of the feed sacks we have talked about and get details of the music at www.hapticandhue.com/listen-series-6

We are taking our summer break for the next two months and will be back in September with some brand-new episodes of Tales of Textiles. But Friends of Haptic & Hue will continue for June and July with a couple of special episodes. But I wanted to sign off this time by saying that we have now reached the milestone of 50 episodes of Haptic & Hue with over 450,000 downloads. No-one is more amazed than I that the podcasts have been listened to around the world by so many of you who love textiles and social history, and I wanted to salute you all, each and every one for coming with me on this extraordinary textile journey over the past three and half years. So thank you for listening and enjoy your making. I’ll be back in September.