Episode #66

Jo Andrews

It’s nearly five years since the pioneering Anglo Trinidadian textile designer, Althea McNish, died in near obscurity in London. In that time her reputation and her standing has grown dramatically and she is now recognized around the world as the one of the first black designers of international standing. There has been a retrospective exhibition of her work, the Victoria & Albert Museum highlights her work, and there is a biography of this remarkable woman in progress.

Althea McNish as a designer was a magician of colour, a woman who brought the light and the hues of the Caribbean to a drab post-war London. Queen Elizabeth wore her dress fabrics, cruise liners sailed with her murals on their walls and she changed the lives of millions with her textile designs. This episode takes another look at the life of Althea McNish.

Notes

Ashley Gray has a website at https://graymca.com/modern-textiles/ and you will find him on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/graymca/

Christine Checinska website is at https://christinechecinska.com/

You can read more about the Althea McNish’s work and the collection of her designs that the V&A museum holds on their website at https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/althea-mcnish-an-introduction?srsltid=AfmBOooI4JRYYIGM0-gtYYGi8wWbsDPohB45DZof2sOZ2LpxcuvqlQrT

And at Liberty of London who still produce a number of her designs for sale in their tana lawn https://www.libertylondon.com/uk/features/craft/archive-althea-mcnish.html

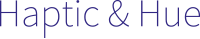

Althea Mcnish – Courtesty of Design Council Archive, University of Brighton

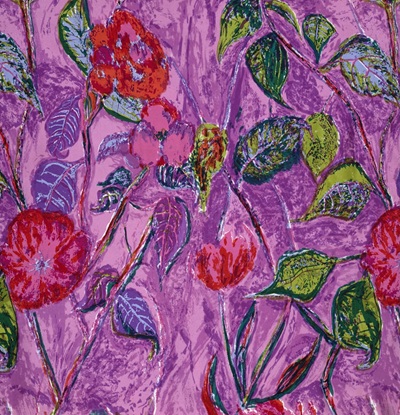

Golden Harvest Furnishing Fabric Designed for Hull Traders 1960s

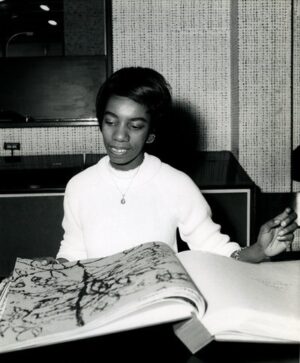

Tropique Dress Fabric, Designed for Ascher Ltd 1959

Bousada Dress Fabric for Liberty of London 1958

Trinidad textile print designed for Heal and Sons

Painted Desert for Hull Traders 1959

Colour is Mine Retropective Exhibition at William Morris Gallery in London

Script

Althea McNish – Queen of Colour

JA: A very Happy New Year and welcome back to Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles and the start of Season Eight. Five years ago, I began this podcast at the height of the COVID epidemic. I thought that it might run for a season or two and then peter out. But it seems that Haptic & Hue opened the lid on a blanket box of extraordinary textile stories and, much to my surprise, has found thousands of listeners around the world. I thought it was only me and a few eccentric people like me who were interested in this stuff. But it seems there are a lot more of us than I imagined.

During that time, we’ve had a lot of messages from listeners asking us to follow up on different episodes. So, for Season Eight here’s something a little different – a number of the best loved podcasts updated with what happened next.

The very first Haptic & Hue episode was about the textile designer, Althea McNish. I had been trying to track her down for some months, and then I discovered that she had just died. I was interested in her because she was one of that generation of women who was responsible for bringing great design into drab post war homes in the 1950s and 60s, and also because she was the first black textile designers of international standing.

But no-one seemed to know much about her. I said at the time that she was remembered here and there with a few lines and an obituary or two, but not with the acclaim she deserved. Maybe it was because she died at a time when so many others were dying too, or maybe it was part of a pattern in which this astonishing woman never quite got the recognition she deserved for her achievements and her talent in her lifetime.

Five years on and that has changed dramatically. Althea McNish is now one of the best-known post war textile designers. Children are taught about her in schools. The William Morris gallery in London has held a well-attended retrospective exhibition about her work, there is a biography of McNish in progress, and the price of her fabrics at auction have shot up. It is an extraordinary turn-around.

So here is the story of Althea McNish from a time when her reputation was just starting its ascent.

Ashley Grey: She’s somebody to be truly celebrated. She brought something truly stunning, a vibrancy, extraordinary knowledge of how to use colour to inspire, how to draw beautifully within a design context, and yet using her life experience really to celebrate the beauty of design.

JA: Ashley Grey is an expert in mid-century textiles, and Alexis Shepherd is a clothing designer.

Alexis Shepherd: She was a groundbreaker and a pioneer in terms of a Caribbean textile designer and artist who came to prominence a very early on, you know, in, in the late fifties before there were many black designers on the scene, so to speak, and I think she’s an inspiration to all designers, but particularly black designers who are students or aspiring to go into textiles or fashion.

JA: The woman they’re talking about is Althea McNish, the first black British designer of international renown. Althea who died in April, was responsible for some of the 20th century’s, most memorable printed fabrics. She was an important part of a talented generation of female textile designers who burst into our lives in the wake of the Second World war. Many of us who love textiles do so because we’re interested in colour, how it blends and shimmers, how different shades and tints alter the way we feel. It can light up a room or make it into a calm, reflective space. Althea McNish once said, colour is mine, and she was right. Her artistic ability and her majestic use of colour detonated an optimism and joy into a drab post-war Britain. She’s also credited with being one of the first people to blur the boundaries between art and design. And because she was producing domestic textiles, like curtains and fashion fabrics rather than fine art, they had a profound impact seeping into homes and lives around the world from palaces to cottages, changing them forever.

JA: This edition of Haptic & Hue looks at Althea’s work as a designer and supports the reassessment of her prodigious talent that has just begun. I can’t help feeling that if Althea had been French or Italian, she would’ve been a household name. But because she was British and a migrant, and because she worked in the relatively anonymous field of textile design, I mean, who knows the name of the person who designed their curtains? – only now is her work beginning to be appreciated. Here’s a snapshot of Althea from Christine Chechinska, curator of African and African Diaspora Fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, who knew Althea in the later years of her life.

Christine Checinska: To my eyes, she was always fabulously dressed. You know, my background is fashion design, so you, I do sort of notice people’s clothing, but she was, she always wore her own prints, and she always had beautiful colors and, and they would sort of be clashing colors, but they didn’t, they somehow worked, you know, they somehow worked. So she might have an orange print with a red cardigan and a head scarf in another bright shade, future pink. And she had these fabulously long and elegant hands, and she sort of spoke with her hands. So she was just like this, this wonderful vision of, of creativity, and always told fabulous stories. Um, and she had this power to, I would say, sort of engage a person and to light up a room. She really did. She was one of these people that you wanted to sit and just listen to for hours, so wonderfully elegant, wonderfully eloquent, and just very, very, very creative.

JA: The first thing anyone needs to know about Althea is that she came from Trinidad.

Christine Checinska: She always said that everything she worked on, she would see it through a tropical eye. I think this is where artists handwritings begin to develop and come out, because I think you do see the world through a particular lens, and it’s almost as though the, the tropics or Trinidad was a blueprint, and that was the starting point. She saw the heightened hues in colors, if you like, and that was what she responded to, so that the, the, the sense of a liking for bright colors, it’s because of the light in the Caribbean. And I think she somehow carried that and applied that, or saw everything through that lens with that light, if you like, almost like putting the world under a light box in which the colors are heightened. So although she might be looking at a typically English scene like the wheat fields, her eye would pick out the golden hues of wheat in a way that perhaps an English artist might not.

JA: Althea was born in Port of Spain, Trinidad’s capital, to loving and educated parents. Her mother was a well-regarded dress maker, and her father, a writer and publisher. She grew up in a world of ideas, books, and fabrics.

Christine Checinska: She talked about her mother being a dress maker, and so sitting in her mother’s studio while she cut patterns, and Althea would do the design drawings and tweak the designs that her mom was working on. So, it was very much a close relationship. She was a, a lone child, only child, very, very close to her parents, and I think her parents had had Althea when they were quite young. So, she always described the three of them almost as a little gang, you know, rather than parents and child. They were almost sort of equals in some respects, but absolutely her creativity was seen at a very young age. So, they encouraged her art classes in Trinidad. She won art prizes. She was apprenticed to artists in Trinidad, and that was all supported by her parents.

JA: But added to that artistic side of Althea was also a careful technical side, a woman who understood how chemical dyes worked, and a skilled drafts woman who took, what one writer describes as a very unusual interest in septic tanks. Here’s her friend, the clothing designer, Alexis Shepherd.

Alexis Shepherd: The most important thing is the way she sort of bridged the gap between art and textiles. She considered print design as paintings in repeat, like I said, the fact that at a very early age, or an unusually early age for a textile designer, she had already many skills to call upon. For example, she had been a cartographer and entomological illustrations back in Trinidad, which I’m sure would’ve sort of honed her skills. And of course, she was immersed in the environment of Trinidad, the flora and fauna, and she would’ve had that sort of wealth of, um, visual references to draw upon in her work when she came to Britain.

JA: By her late twenties, Althea was a successful artist and had good technical skills too. At this stage, no one could have predicted that she would become a textile designer. She came to it by a roundabout route. Althea’s father, Joseph McNish, got a job in Britain as a result of that. Althea applied for and got a scholarship and food grant to cover the costs of studying architecture in London. And in 1951, 3 years after the Windrush sailed for Britain with the first post-war Caribbean migrants, Althea and her mother left behind the light, the warmth, and the colour of a comfortable and successful life in Trinidad. They swapped it for the gray drabness of a scruffy, broke, post-war London. It must have been extremely hard, but there is a sense in which Althea never left Trinidad all her life, she carried it safely, stored within her, and expressed it in every piece she ever created.

Ashley Grey: There was no surrender about having to conform to something that was already happening here. What she was doing was bringing the, these vibrant colors, and again, the, the, the way of looking at textiles. You, you, you talk about looking at textiles as as fine art to my mind, she’s an example of somebody who had that fi fine artist aesthetic in her DNA already. Really.

JA: Ashley Gray is an expert in mid-century textiles. He believes that Althea arrived in Britain at just the right moment.

Ashley Grey: The timing of this, again, is so perfect. I would compare her to Marian Mahler and Jacqueline Groag and others, somebody who was arriving, on these shores who was bringing their, the richness of their experience with them.

JA: She quickly abandoned the idea of a long training to be an architect, and instead swapped to a shorter course at the London School of Printing and Graphic Arts, and in the way that our lives can change on a chance. While she was there, she went to an exhibition of textiles by students at the Central School of Art. She was interested, and as a result, enrolled on evening courses at Central. Ashley Gray says it was a good choice.

Ashley Grey: At Central before she into the Royal College. You had this more radical approach to the arts that understood that there was a wider context that wanted to influence beyond just the oil on canvas or, uh, or the drawing. And understood that textiles in a domestic arena was a way of literally a key of unlocking the door to modernism in the home. These textiles that Althea was producing were bringing something new and vital into the home.

JA: And there at Central, she meets Eduardo Paolozzi, the legendary Scots Italian teacher and radical civic artist, the man who became known as the father of pop art,

Ashley Grey: But it’s Eduardo Paolozzi who, who then says to her, you should be doing textiles. But he doesn’t do it in the same way as was said to so many other women at the time, oh, go and do it. It’s what women do. <laugh>, because of his role at, at Central and his thinking, uh, with that radical group of artists, he knew that she could actually bring something exciting into the home. On the one hand, you had those who were genuinely talked down to in terms of, oh, well, really, I think you should be doing this. It’s really what the women should be doing in this case. I don’t believe, uh, that that was what took place. I think it was a more innovative discussion about where to go with, with this form of art.

JA: And Althea McNish richly repaid his confidence. She graduated from Central and later from the Royal College of Art in 1957, with a rare combination of talent, technical understanding, and the training to become one of the finest textile designers Britain has ever seen. The day after she graduated, she was summoned to the London Department store liberties to meet the chairman Arthur Stewart Liberty. He commissioned work from her there and then and bundled her into a taxi to meet Zika Asher Europe’s best-known designer of art fabrics, particularly silk squares, Zika, and his wife leader, commissioned work from people like Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore, Picasso, Matisse, Cecil Beaton, and Althea McNish. He immediately commissioned her to produce designs for Christian Dior.

Ashley Grey: Often what the, the note of the genius is, the genius recognizes firstly, that less is more, and secondly, understands when to stop and not to overdo a design. When you look at Althea niche’s, textile designs, you see that incredible confidence of an artist and a designer who completely recognizes that they don’t have to go on and on and on and on. They can give the impression of a sunflower or something like that. Those subtle marking on the initial drawing, and then the fire blazing, the colors blazing from behind. But then yet, at the same time, the reason it works is because of the subtlety. Because of that genius of knowing when to stop, that was in her DNA.

JA: Althea’s almost immediate success meant that she didn’t need to become an in-house designer. Instead, she could establish herself as one of a small band of freelance designers with the independence to experiment and the freedom to produce work they liked. She sold designs to most of the UK’s leading firms, including Heals and Cavendish textiles. She worked for haute couture houses, including Dior, Schiaparelli, Givenchy and Lanvin, for textile firms in Paris, Milan, and Lyon. She designed murals for British Rail and for the restaurant of the cruise ship. SS Oriana, her prints appeared in the top European fashion magazines. And when Queen Elizabeth went to Trinidad in the early days of independence, she was dressed in Mcnish designs.

Christine Checinska: And I think Althea absolutely blurred the boundaries between design and art. And maybe she was one of the first people to do that. I know that that’s very much the way that textiles are taught now. There is that kind of blurring, but I think she, to my mind, is one of the first people of note to actually do that. Because that was just the way that she was. There was certain things that she wanted to express through a fabric design that would be worn, and other ideas that she wanted to express through a mural that might go on a wall, or it might be a painting that would sit in, you know, in a state office. But there were all different aspects of the one artistic voice.

JA: She created her most celebrated, designed Golden Harvest after a weekend in the Essex countryside, walking through golden wheat fields there and recalling childhood walks through rice fields and sugarcane plantations in Trinidad, the design successfully fuses an English country scene with the deep colors of the Caribbean. It sounds as though it couldn’t possibly work, but it does gloriously. It became the bestselling design ever produced by Hull Traders, one of the most prominent design houses of the era. Althea’s success rested partly on her ability to speak the language of the production process. And she once said that whenever printers told me it couldn’t be done, I would show them how to do it. And soon the impossible became possible.

Christine Checinska: She was well educated, she was striking, she was creative. Her technical knowledge was second to none. So, she would go to factories, she would go to, you know, in this country and in Italy, for example, I remember her saying, and because she could run rings around the technologists, she knew more about printing than they did. She just won everybody over. And I think any comments that she received, she would always say that it was water off a duck’s back, you know, because her mission was to create these works to, to produce her painting, to produce her fabrics. I can imagine some people just completely dumb struck, actually, <laugh>, uh, you know, when they met her.

JA: Althea was a young, striking black woman working in a very white Europe. And yet she said she never experienced discrimination adding, I was so rare, they were dumbfounded. Her friend Alexis Shepherd says that she was often the only black person and the only woman in the room.

Alexis Shepherd: She acknowledges that she was something of a rarity at that time, but she was warmly received generally by people in the, uh, textile business. She was unique in that sense, and she had the confidence, and the work was, was so good. You couldn’t argue with the work. I think she was so focused and so immersed in what she was doing creatively. She maybe didn’t pay much attention to what we might call today, microaggressions, or the little slights, which sometimes people were targeted with in those days. And still today, she was protected. She sort of had a, a protected aura around herself.

JA: And Alexis says that people might have known her name, but often they didn’t know who she was.

Alexis Shepherd: Even, um, her husband, John Weiss commented for years when he was an architect, he often had the opportunity to use Althea’s textiles for part of his work. And he said for years he thought that she was a little old Scottish lady because of her name, Althea McNish. And, uh, he was surprised to find that she was a, a black woman from the Caribbean. So, I think the textile designer, unlike perhaps a fashion designer, is less, uh, visual. They’re not as visually recognizable as a fashion designer is. So, um, the work speaks for itself.

JA; Christine Checinska remembers Althea describing a skiing trip.

Christine Checinska: She was an educated and cultured women, so she did go on skiing trips and she said that people would just stop and stare. It was almost as though they’d never seen a, a black woman on a set of skis, and they probably hadn’t. She had a great sense of humor, and I think she just thought it was quite funny to watch people’s reactions because they clearly had never seen a black woman on skis. And remember, she was really tall as well. So she used to, she modeled at one point in some of the French fashion shows. So she was this tall, willowy, stunning woman.

Jo: Christine says, Althea rose above it all.

Christine Checinska: She never really dwelt on the difficulties. And I think she just saw life as a challenge. And she saw all of these things as frameworks from which she could then become more creative. She never saw anything as an obstacle. And I don’t think I ever really had a conversation where she dwelt on hardships. She never spoke about that. She just saw everything that happened in her life as more Christopher, the mill of her creativity, if you like.

JA: Nonetheless, Althea McNish has not received the same profile and the same accolades that her white colleagues have. There is no foundation named after her, no permanent collection of her work. She was hugely successful, but lived a modest life. She was never honored for her immense contribution to British exports at a very difficult time in Britain’s history, or for her long years of teaching. Here’s Christine.

Christine Checinska; She’s so important. It saddens me as someone that has worked in the fashion industry for over 30 years. I didn’t hear about her work until I was sort of in my forties. I don’t want young fashion and textile students of any race, but particularly designers of color, artists of colour coming through not to know of her practice, not to know that she was in London in, in the 1950s, kicking up a storm at the RCA and selling her collection to Liberty. Because how empowering is that story? And I think the way that she handled, she must have experienced racism. I think everyone of colour does at some point, but the way that she was somehow able to elegantly rise above that and to produce fabulous work regardless and, and let her work talk for her in some ways is really inspiring. I think, I think we can all learn a lesson from that.

Jo: And Ashley Gray believes her contribution as a migrant to Britain is important.

Ashley Grey: She symbolizes for me in the wider story of this fascinating area of textiles. She symbolizes that whole point that within Britain, we may have had the raw materials, the wool, but we needed the innovation. We needed the ingenuity, we needed the vision of those who could come and work and understand and produce something beautiful, uh, with what we had here.

JA: Christine Checinska says there is beginning to be a reassessment of her career.

Christine Checinska: I think this is building momentum. Obviously, it was awful when we lost her this year. But with that, I think many people are gathering to re-look at her work, to acknowledge the contribution that she made to the British textile industry, and to acknowledge the inspiration that she was and is because although she was conscious of her contribution and her legacy, there was an interesting modesty within that, or a humility within that, which is very attractive, I think, because when she passed, I remember there was a sort of a flurry of, um, messages just on social media from, you know, artists who are possibly more household names than she is saying, oh, yes, I met Althea when I was an art student. She came and marked such and such a project, or she came and judged this, or she came and did that. So, I think that her influence is there in in generation upon generation of creative, black artists, and designers. And we, none of us really knew that. So, I feel that there is this kind of reassessment, and I feel confident, that there will be a kind of a flourishing around Althea’s practice, and that her legacy will be secured, as it should be, the sadness, of course, is that now that she’s gone, they can’t talk to her firsthand. And I’m so relieved that this is a sense of a garnering of interest around her work.

JA: And a concern from Christine Checinska, ever the museum curator that Althea’s work shouldn’t be lost to future generations.

Christine Checinska: I would welcome any materials, whether it’s notebooks, whether it’s artworks, whether it’s fabric, whether it’s scrapbooks or newspaper articles on her. I would welcome anything like that because I feel that in the museum we have the skills and we have people that are able to do the conservation work that are able to preserve her notebooks, artworks, fabrics for future generations to enjoy. And also, we have people that can gather the stories. You know, I’d love to speak to women that wore her clothes and to hear their stories of their first encounters with Althea’s clothing. You know, what difference did her wonderfully magical exuberance prints make to their lives? So there is a, there’s a body of deep, deep research work that could be done if we were able to access that archive and bring it into an institution somewhere where this work, where there are skilled people that can do this work. It’s not about us and our glory. I’m saying this because I am passionate about Althea’s work. I’m passionate about her legacy, and I want to share that, you know, I want, I want others to experience this, this exuberant, generous, creative woman that I experienced. Others can do that through seeing the brush stroke on paper. If we can find and gather those pieces and bring them that together.

JA: Some of that research into Althea McNish’s remarkable life has started, as she finds her place in the first rank of post war textile designers. If you would like to find out more about her and see pictures of some of her work, there are links to further articles and websites on the page for this episode at www.hapticandhue.com/listen and look for Season 8.

In the upcoming episode of Friends of Haptic & Hue – which goes out on the third Thursday of every month – we will be investigating rare medical samplers that were made to show surgeons how to stitch in 18th century Germany and Switzerland, and we will be talking to the textile archaeologist and heritage crafts teacher Sally Pointer about the difference between knitting and much more ancient nälbinding.

Sally Pointer: And when we look at, some of the earliest woollen näbinding, we’ve got some lovely pieces from Coptic period Egypt, which are children’s socks and really cheerful stripes. Now we, we’ve always loved putting children in bright clothing and I’m sure 2000 years ago nothing was different, but absolutely brilliant use of short amounts of what would otherwise be expensive died yarn is to save up the few arms’ length of this, a few arms’ length of that, and make your toddler a pair of stripy socks. It’s just wonderful.

JA: That’s all in the new Travels with Textiles on Friends of Haptic & Hue and if you are not already a member, you can find out more at www.hapticandhue.com/join Haptic and Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews. It is edited and produced by Bill Taylor and sound edited by Charles Lomas of Darkroom Productions. It is an independent podcast free of ads and sponsorship, supported entirely by its listeners, who generously fund us through Buy Me a Coffee or by becoming a Friend of Haptic & Hue. For now, until next month, its good bye from me and please, enjoy whatever you are making.