African Wax Cloth

A Long and Winding Tale

Episode #22

The is episode explores the curious origins of African Wax Cloth and the twists and turns in an extraordinary story that is behind the creation of one of West Africa’s most iconic fabrics. It’s a journey from Java to West Africa, via a small town in The Netherlands, it’s a tale that upends the idea that textile production always exploits women. We travel through a history where astute African businesswomen helped to redefine their countries’ relationship with their colonial pasts. And like all good tales, this has its dark side – from the ruthless trading tactics of 19th-century Dutch colonial merchants to the brutal economic realities of modern-day textile production. It’s a story ultimately of resilience and triumph and the creation of a new design ethic from chance encounters.

This episode runs for 39 minutes.

A big thank-you to Dolapo James and Jessica Hemmings for their help with this episode.

Dolapo runs Urbanstax, which you can find at https://www.urbanstax.com/ or on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/urbanstax/ And Facebook https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=urbanstax. An article by Dolapo on African Wax Cloth is at https://craftindustryalliance.org/buying-and-wearing-african-wax-prints-an-exploration/

Jessica Hemmings is online at https://www.jessicahemmings.com/ She is best known for her book, The Textile Reader, which is a wonderful collection of articles and writing about Textiles. It is in the Haptic and Hue book list for this series. It can also be found second-hand on Amazon or Abe Books. Access to Jessica’s interview with Vlisco is at https://www.academia.edu/50902105/Dutch_wax_resist_textiles_Roger_Gerards_creative_director_of_Vlisco_in_conversation_with_Jessica_Hemmings. It was also published in a book called Cultural Threads: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/cultural-threads-9781350171756/

A number of artists use wax cloth in their work – many people will know of Yinka Shonibare’s work, you can find out more on his website. http://yinkashonibare.com/. There is also the current work of Lubaina Himid, which is on display at Gawthorpe Hall for the British Textile Biennial. You can see and hear the artist talking about it at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=403tfQB9oTQ

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Dolapo James, Founder of Urbanstax

Speedbird, Dolapo’s favourite wax print

Darling Don’t Turn Your Back On Me

Jessica Hemmings, Professor of Craft, Gothenburg

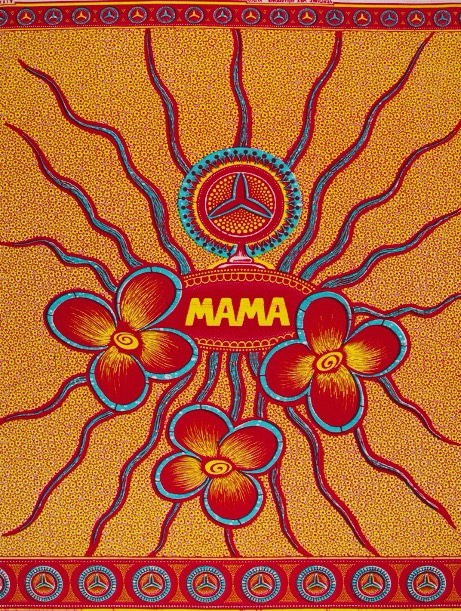

Mama Benz Cloth, Vlisco Fabrics, Made in The Netherlands

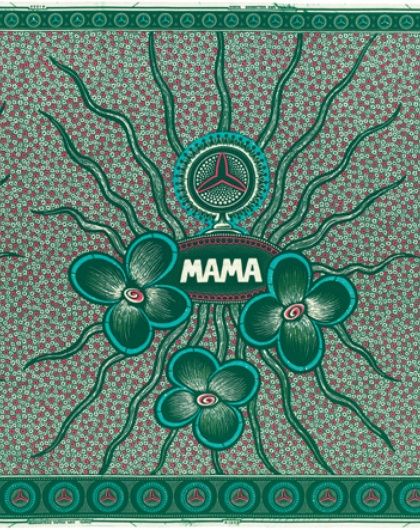

Mama Benz Cloth, Vlisco Fabrics, Made in The Netherlands

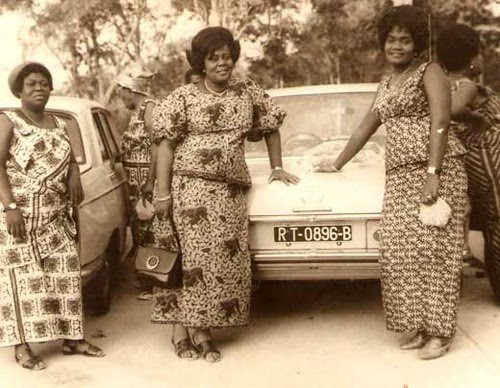

Nana Benz in Togo with a Mercedes.

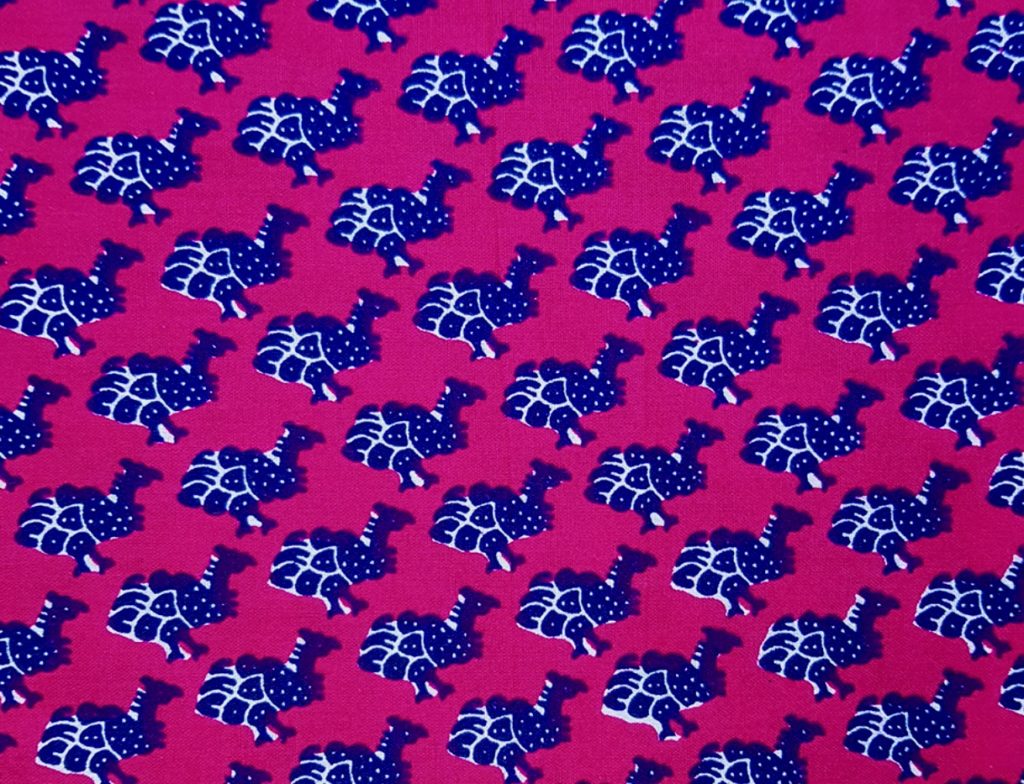

Fuschia and Blue Guinea Fowl made in Ghana

Purple, Blue and Green Fronds made in Ghana

Wax cloth made in China

Green and Maroon Arrow, Made in Ghana

Record or Wishing Well, made in Ghana

African Wax Cloth

Script

There’s a cloth that has been storming the catwalks and filling the shops of the world for some time. African Wax cloth or Ankara cloth is having its moment in the sun. From couture houses to high street stores this stuff is everywhere, in a riot of designs and colours. And these intensely joyful patterns have been added to the ever-growing list of fabrics that have soared beyond their origins and taken flight globally. They can be found in small provincial drapers’ shops in France, smart department stores in Australia, and in interior design shops as far as apart as California and Calcutta.

But the story of this fabric is a strange and surprising one with many twists and turns, it’s a journey from Java to West Africa, via a small town in The Netherlands, it’s a tale that upends the idea that textile production always exploits women. We travel through a history where astute African businesswomen helped to redefine their countries’ relationship with their colonial pasts. And like all good tales, this has its dark side – from the ruthless trading tactics of 19th-century Dutch colonial merchants to the brutal economic realities of modern-day textile production.

It’s a story ultimately of resilience and triumph and the creation of a new design ethic from chance encounters.

At the centre of the tale is Dolapo James, a businesswoman who sells wax cloth all over the world. It is something that is in her blood and has been part of her family’s life for generations – her grandmother sold wax cloth from her house in Nigeria:

My grandmother ran a fabric shop in a state called Ondo State. That’s where my dad is from. She, she sold different types of fabric, so she sold lace, but she also sold wax prints. So I think probably my earliest memories are sitting in a shop and it has a very distinct smell and smelling the fabric and watching her interact with customers and sell them this fabric. But also it’s a fabric that my mum would buy and make little outfits for, for us as children. It’s what you would wear to the markets if she went shopping. So yeah, it’s, it’s, it’s like sort of everyday wear, but that my earliest memories would probably be sitting in my grandmother’s shop as she, as she spoke to customers and selling the fabric. I think the bold patterns and colours definitely appealed to me because they are so vivid. And I do remember it and actually speaking to my sister, even recently, we have similar memories where she would say, we call my grandmother mama, I will say, oh, remember mamas Ankara that’s had that pattern or colour or would find a picture and we’d both be like, wow, I remember that one. So I think maybe it’s something about just the sheer boldness of the designs, but absolutely very distinct memory of always wanting to touch them. I’d help her hold the fabric when she was cutting it. Yeah. So I think, I think as a child, it definitely just drew your eye, something you wanted to touch and play with even.

Dolapo thinks her grandmother made a reasonable living doing this:

I don’t know, but the setup was an interesting one because her shop was actually in the house. So it wasn’t the front of the house in front of my grandfather’s house. And the road is quite a busy road and people would constantly in and out of the shop. So I can only guess that she did. I have to be honest. I’m not entirely sure. She was always busy. That’s a good, that’s a good indication.

Welcome back to the third series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles, which is called The Chatter of Cloth. My name is Jo Andrews and I am a handweaver interested in how textiles speak to us and in trying to unravel the meaning they hold in our lives.

This episode is about African Wax cloth, what it is and where it came from. To help us unravel this story, Jessica Hemmings, currently Professor of Craft at Gothenberg University and a writer on all things textile, has chosen an unusual wax cloth. It celebrates women – like Dolapo’s grandmother – who made their living by selling wax cloth – not in this case in Nigeria but in the close by West African country of Togo.

So the Mama Benz cloth is made by the Dutch company Vlisco and we are talking about a relatively recent design. So it was made in produced in 2010, but it is in recognition of the women who traded and continue to trade Vlisco cloth in the country of Togo. it’s on a mustard orange background, you could say. And it has the rather iconic Mercedes Benz logo as the centre feature of it. With rays radiating out, it comes from a series of cloths by Vlisco called Sparkling Grace. And you can see the adaptation of the car manufacturer’s design in the centre, but it’s also accompanied by three, three flowers and an additional logo beneath the Mercedes Benz one that we’re so familiar with the letters that spell out Mama. And the explanation for the story behind this cloth is that the trade of Vlisco fabrics in Togo is a matrilineal agreement. So, it passes from grandmother to mother, to daughter through the female side of, of families with licenses granted by law. I understand. So you have quite a, quite a formal agreement. And we often think of textiles as something that contributes to the oppression of women, maybe particularly in developing contexts. Textile labour can be very poorly compensated. Factory working conditions can be highly problematic, but this is a little story of an inversion of that because of the matrilineal agreements to, to the licensed, to, to trade Vlisco in Togo. It meant that the Mama Benzs and a woman in particular, a woman called Madame Rosa Crepie was the first person to own a Mercedes Benz, as I understand it, in the country of Tog in West Africa. To have the affluence to be able to purchase a car of such financial significance was through the profits of the cloth trade. So, I always like to refer to it as a story of the textile trade which is not always about the oppression of women. It often is, I’m not naive enough to deny that, it comes with very, very significant problems, but we also, we also have examples where it, it, it absolutely contributed to something very, very different. And this is actually about the financial empowerment in this particular context.

In the 1960s and 70s This cloth played an important role in enabling women to establish a level of economic independence, In Togolese Mama is said as Nana and in a lovely piece of language re-purposing, the daughters and granddaughters of the original Nana Benzs’ – who have inherited their grandmothers’ shops, are known as Nannettes.

Wider than Togo these densely patterned and highly coloured fabrics have come to be an integral part of what it means to be a West African, a signifier of identity. Here’s Dolapo again:

I do think that’s fair because it’s, yeah, it’s, it’s, it’s so woven into people’s existence that actually it’s, it’s hard to separate.So when somebody was getting married there’s this sort of a tradition of the groom’s family, given a bride sort of present in a suitcase. And one of the things that would always be included would be wax print. So by, so, I mean, so now that that has filtered into marriage sort of wedding, so what, how do you start to even separate this? So I, I absolutely do think of them as African now.

But as Dolapo suggests, the story of wax cloth begins in a different place altogether, a very long way from Africa. The company Jessica talked about as the producers of the Mama Benz cloth is Vlisco. It is based in the Netherlands near Eindhoven and curiously, for over 100 years it has dominated the trade in African Wax cloth. The reason behind that begins thousands of miles away in the Indonesian archipelago. In the early 1600 Dutch colonisers began arriving in what was then Java in search of valuable spices and a land to colonise, and they remained the colonial power for 300 years, in the 19th century they had an idea. Jessica picks up the tale:

It’s a long story, and it has many, many explanations, which at this point it is very difficult to confirm the accuracy of, of everything. But the Dutch colonized, the islands that are present today, Indonesia. And one of the things that they did was look at the textile traditions and batik in particular, which is very much the textile tradition of the island of Java. And they decided that there could be a business opportunity in this, if they mechanized the production in, in the Netherlands they could possibly produce the cloth more quickly, more efficiently and sell it back to the islands for a profit.

But this didn’t work out in quite the way the Dutch manufacturers hoped.

But what we understand is that the local market rejected the Dutch imports of the cloth. And there are a lot of explanations as to why the poetic one is that the mechanized cloth production brought in flaws that the local market disliked that’s that’s a lovely, poetic explanation, but another one that researchers have put forward is that there was also a system of taxation, a system of taxation that the Dutch imposed. And so they may have been cannibalizing their own idea that the Dutch imposed on an on import to preserve the value of the material culture of the islands that they were colonizing. So it, it could actually have, have been money rather than aesthetics that, that caused that first idea not to work

It has also been suggested that in Java hand-made batik had a particular smell, which the Dutch, machine produced substitute didn’t have – so it wasn’t accepted as genuine, but Jessica Hemmings, who is a specialist in Javanese fabrics, points out that in this region batik isn’t just cloth, to buy and dispose of easily – it is a fabric that has great ceremonial meaning for Indonesians– even today.

I think that batik in particular is a very strong example of a living tradition. It does have UNESCO world heritage status as an intangible heritage. And even today there’s a day of the week designated for everyone to wear batik. Government employees would use batik clothing. So it’s, it is something that has remained utterly, utterly alive. It’s an odd idea, isn’t it? So the finest most valuable cloth where the wax was drawn, drawn by hand, and that batik is a design technique that requires the maker or the designer to think backwards. You, you maybe could say, so the colour is not being layered or added, but the wax is protecting pieces sections of the cloth from being exposed to the dye bath. So you have to think in inverse layers, whereas the lots of, if you think about how somebody would paint a painting, you would build up the colour, but this is, this is thinking in the other direction, it’s incredibly labour intensive and time consuming. And I think that the Dutch agenda in what we call Indonesia today was a trade. They weren’t particularly interested in learning about the local culture, it really was about the profit.

But even though the cloth was rejected in Java it found a welcome home somewhere else.

And so the journey, if you bring, bring to mind them, the map of the globe, we’re traveling all, leaving the Netherlands and traveling all the way down the west coast of Africa, all the way around the Cape. In, in South Africa and over to the, what was then the Dutch East Indies, a very long journey, they needed to refuel along the way, and they were stopping along the west African coast to do that. And the cloth found a welcome, a welcome market there. People have put forward the idea that there were mercenary soldiers, particularly from Ghana who travelled to the Indies and may have brought the cloth back as gifts which could have established a certain taste for this, for this cloth in, in west Africa. Others pointed out that that’s unlikely the salary of a soldier wouldn’t necessarily have covered that type of gift being brought back with them. So there’s tension over, over which piece of history is correct, but regardless of disentangling those, those suggestions of how it’s occurred by the time we get to the fifties and the sixties, when the Western central African nations gaining their independence from colonial rule, this form of textile tradition is what many of them looked to when building new national identities. So there’s a real irony in a colonial project then becoming an emblem in a different part of the world of post-colonial national identity.

So a cloth with its design roots in Java, made in the Netherlands had by the time the 1950s and ’60s came around become an emblem of West African and Central African identity. So much so, that when Congo became independent from Belgium, the new president decreed that people HAD to wear wax cloth to demonstrate their Africanness. This gave Vlisco in the Netherlands a welcome boost in sales. But the Dutch weren’t the only people producing cloth for the West African market, the English also produced their own Wax cloth. And For West and Central African consumers, one of the attractions of this cloth was that it came from abroad, it was new and fresh and it was quality: Here’s Dolapo again:

The batiks, the wax prints, even in the wax prints category, people would differentiate and go, oh, I have Dutch wax. I have English wax. It wasn’t referred to as African, it was referred to as Ankara or Dutch wax or English wax. So it, in my mind, I didn’t think of it as being any particular thing in a sense it’s, as I got older, that I, this association with it being African sort of seemed to establish itself, may be speaking to the older people in that time, they, they might have a different view, but as a, as a younger person, this, this was what I thought.

But as much as West African consumers perceived that were buying cloth that was interesting because it came from abroad, so too in the early 21st century this astonishing fabric is now seen by non-Africans as fresh and original precisely because it comes from Africa: And Dolapo believes it has earned its right to be seen as African.

I do think it has an African identity because over time it’s, it’s become part of the parcels of peoples it’s, it’s become part of our culture, essentially. Yes, the origins are not necessarily African, but that sort of exchange has happened where fabric would be sought in Africa, depending on their popularity or the motifs on the fabric, they would, you know, stories will be ascribed to them. And this has now become part of the histories of these countries. And also the fact that production then did move into African countries, gave them even more of sort of an ownership of the fabric, where the fabric was designed in, in, in these countries and producing these countries and warning these countries. So it’s sort of like it’s evolved. So I do think of them as Africa now, actually,

And some of those stories that have become woven into the different designs are wonderful:

So my absolute favourite is one called the sweet bird, which is like a motif of a bird in sort of an oval shape. And in Ghana, apparently in the markets the phrase that goes with that fabric is ‘money has wings’. And the idea is that if you’re not careful with your money, it’ll fly away. So that is one of my absolute favorite ones, not just because of the story, but I actually really liked the motif and it comes in so many beautiful colour combinations.

Another glorious cloth is called Santana or alternatively and delightfully: Darling don’t turn your back on me:

I think that was down to a particular seller who sold a vast amount of it. But the idea is that if I’m a wife was, if a wife was upset with her husband, she would turn her back on him and it was, you know, please don’t be angry or don’t be annoyed with me. And I mean, the motif is almost like a twist and turn. So again, that one is quite interesting. Another very popular one is, has many names. You, hear it referred to as record, you hear it referred to as well. So it’s sort of like a big disc. Again, that comes in many, many colors, I think sometimes it’s even called the wishing well so a particular design in different countries might have a different name.

Fabric is also used as a way to commemorate events, both national, international and family events. Most of us will have seen fabric with Nelson Mandela’s or Barack Obama’s image printed on it.

So when something, you know, monumental is happening or a new precedent or something, something historical, the manufacturers would release a print, a limited edition print with the, with the face of, of, of the person usually for a limited run. And then that will be it. So it’s, it’s, it’s actually quite common. Even it’s even for lesser-known people. So in Nigeria, if there’s a chieftaincy or sort of coronation, but the group or the society, or, or whoever would go to the manufacturers and they would print huge runs of to commemorate that event

And Vlisco as a company has survived where all the other overseas companies producing this kind of cloth have folded because it has worked very closely with individual traders in Nigeria, Togo, Benin, and Ghana and adapted its designs to what they want. Even so, there is something bizarre about the designers of these vibrant strong fabrics, sitting in The Netherlands. Here’s Jessica Hemmings again.

My understanding of the company today and I, and I couldn’t vouch for how far back this goes, but my understanding of the company today is that they’re designers that are based in the Netherlands are admittedly pre our current pandemic travel restrictions, but they are all supported to travel to the countries where Vlisco has the strongest market because you can imagine the design challenge of sitting, sitting under a Dutch sky, very much like an English sky, a completely different colour palette outside your window. And the Vlisco fabrics tend to have an incredible vibrancy to them. And so the designers are encouraged to take research trips to ensure that they are understanding actually the interest of the market that they are designing for.

The Creative Director of Vlisco, Roger Gerards, told Jessica Hemmings in a rare interview that he gave some years ago that when his designers, who now come from all over the world, go to West Africa they develop a much stronger bond with the consumers of the fabric. Fifty years ago as the countries of West and Central Africa became independent there was a sense that the production of this cloth should and could move closer to the consumers. Here’s Dolapo:

I think at the time a lot of African countries and West African countries were gaining their independence from the colonial times. And there was sort of new vibrancy. So things were becoming more industrialized. I mean, somewhere like Nigeria, for example, they discovered oil. So it became a very wealthy country quite quickly. So the government was essentially prosperous and you know, factories were being set up and there was sort of a more positive outlook to everything. So this obviously fed into this aspect of, the economy. So from my understanding, they, they were quite a lot of factories up north in Nigeria, as well as a few down in the south of the country. The cotton was being grown, it was being processed and it was being used in these factories. So other African countries were being exported to because they were also experiencing this sort of newfound independence. So a lot of African prints from Nigeria ended up in Ghana and the general sort of West African region. So this is my understanding. It might not be entirely accurate, but this is what I understand happened so that the Dutch on wax prints, although still very popular and actually sought after, because it was seen as, you know, I guess a little bit more unique or exclusive because, you know, they came from somewhere else, but they were the production. Nigeria was then of course more affordable. It’s not an import. So it was commonplace to actually just wear a Nigerian print in the more every day. And then the Dutch and English prints for, I guess, maybe slightly more special occasions.

But sadly this didn’t last and today very little cloth is produced in Nigeria itself.

There’s one or two that are on paper still in existence, but in terms of production, I do know that anything is coming out of those factories, except so they still have this huge market in what we call Aso Oke. So when there’s a funeral or a wedding, people will wear the same cloth. So what has happened is that to make it that bit more special, they will go have it customized and they’ll order it in bulk from these factories. So my understanding is that they still have that side of things going, not in a big way, not in the kind of way that will sustain the sheer, sheer scale of these factories, but I’m aware that that is something that they still do. And similarly, as I mentioned, for like political rallies and that kind of thing, they will print customized fabric. But in terms of, you know, the one-off designs that they run on and sell wholesale, that reaches the markets there’s, as far as I can find, nothing,

Dolapo says this happened because of a combination of factors:

So over time, a combination of things have happened to the economy in Nigeria it has taken a dive. The interest in certain aspects of the economy has, has, has been diverted away. Chinese imports unfortunately have pretty much nailed the coffin shots because they’re so much cheaper than anything that can be produced in Nigeria. Niger has infrastructural issues. How has supply transportation amongst other things, but to my mind, those are the obvious ones. So production is expensive compared to these imports. So people can only vote with the power of the pocket. They will buy the cheapest stuff there. There’s no sort of solidarity when it comes to that. You either have it either can’t afford it, or you can’t.

And here is the next chapter in the wandering journey of this cloth – China – currently the premier fabric manufacturer to the world started making wax cloth – more cheaply than elsewhere.

So initially when I would go to the markets and pick stuff up, I would note the brand and put it through, the washing machine or wash it by hand and see what happened. So initially it would run, it was often imitations of Vlisco, the Dutch brand. So initially it was actually pretty poor. Some of it had a high synthetic content and just not great, but I have to admit that that’s changed over the years. The quality is fine, the design again, and you find there’s such a huge variety. I mean, it’s down to taste now. It’s not, it’s not the case of the designs are awful. Some of them are fantastic, but my issue would have been, or is, the starting points. And actually what still carries on, which is a lot of it is imitations of existing designs of existing African brands, as well as the Dutch and English brands. They’re just copies. They’re just direct copies. They are relentless in the copying. But in terms of the fabric, it, of course, there’s a huge, huge range, but I’ve come across some that they wash fine. They, the designs are fine, the colours are fantastic. It’s, it’s down to taste it’s down to whether or not you like one design over the other.

And here is part of the clue as to why so much wax cloth is currently around in our stores and on the rails of clothes shops. It is being produced in China in a huge number of designs far more cheaply than before. And this is where Dolapo’s personal journey intersects with this story: she began using this cloth in her own accessories business.

And I found that there was a lot of interest in it, but in order to source more of the fabric and use more of it, I also wanted to learn more about it and then discovered that it had almost this darker side where a lot of it was being copied. A lot of it is not even made in African countries but is sold as such. So for me, it’s almost like a learning experience as well as a little way of promoting actually stuff that is made in African countries and is beautifully made and has a history or a scale or a craft that needs to sort of be highlighted rather than just copied or forgotten. So for me, it’s about trying to source, fabric that is made in African countries and send them out to other people in different countries that are interested in this fabric.

She set up her business Urbanstax which focuses on cloth that is genuinely made in Africa – but it’s a tough journey trying to educate consumers about what they are seeing and what they are buying.

Sometimes I feel almost like I’m fighting this losing battle because I will not buy a fabric that isn’t produced in an African country. This is not to say some of these companies sometimes are owned by a European company, some sort of parent company somewhere else. But, the key thing for me is at least as a starting point, is that the fabric is produced in an African country, which means it’s employing African staff. It has a factory that’s physically there, which has been paying taxes and you know, all that stuff. But the general feeling is that once it looks a particular way, it has to be African. This is so wrong. And I belong to a lot of sewing forums and groups and Facebook groups. And I see this almost on a daily basis where people will say with great pride, that they bought six yards of fabric for five pounds. And I think if you just stop to think for a second, that doesn’t make sense, because if you accept that, actually probably isn’t African fabric and you’re buying it because that’s what you want to buy, then that’s fine, but it’s not because it’s African fabric that is five pounds. It’s because it’s an imitation or it probably isn’t cotton or, you know, various other things.

Dolapo says that she has endless conversations with customers who come to her stand at many of the shows she goes to, and they ask the same question over and over again: Why is your cloth so expensive compared to the fabric I can buy in my local fabric store?

I’ve had people who have refused to buy the fabric I sell because they don’t see why they should pay 60 pounds for six yards of fabric, but actually will come back because they went and bought the one that was a fraction of the price and try to wash it and then, you know, ended up with the results they ended up with. So it’s, it’s frustrating, but I also think it’s, it’s a bit of a slow process where you almost have to justify why the fabric deserves to be treated, just, I mean, people would pay 25 pounds for a metre of fabric that was from Liberty, it’s been designed by in-house Liberty designers, you know, and whatnot: And yes, they have a history, but why should African wax be that different. It’s been designed by this young student who’s come out of Yabba college of technology. It’s been produced by the kind of person that would wear it. You know, People will see this stuff and not question it, but they’re not bad people. They just don’t know. You know, the thing for me is always the clincher, the clincher, which is the price. If, if you, if you think six yards of fabric at 10 pounds make sense, then I don’t think there’s much. I can tell you.

The story of Wax cloth whether it is Indonesian, African, Dutch, English, or Chinese points up for me one of the most interesting things about cloth, which is that it changes its meaning for the people who buy and wear it depending on the context. The same cloth can do different things for different people, it can say that you respect tradition, that you are wearing something of quality made abroad, or that you support this political party or that you are a member of this family or, simply it can say look at me – I’m wearing something interesting that comes from Africa. Jessica Hemmings believe this cloth with its complicated backstory is something that belongs both to West and Central Africa and is also a global phenomenon.

Would it be possible to say yes to both? It, it has very particular connections to two parts of, Africa now, that should be acknowledged, but the history of how it arrived there and where it came from is part of that story as well. And I think that maybe where these conversations sometimes run into trouble is hoping to find that type of singular explanation or answer that trumps all of the other answers. To say it’s African at the expense of acknowledging that the tradition is also alive and utterly vibrant with deep historical roots in present-day Indonesia, that’s s inaccurate because it has its own meaning and purpose and use there as well. So it’s not African cloth at the expense of not also having, having its relationship to, to the Indonesian islands. So I, I think that maybe if, if we can start to accept that sometimes the answers to these questions are multiple and different, and with pieces of history that’s that we have to take with a pinch of salt and recognize that many of the pieces of records that remain are very skewed as far as they are European records of what this is. So we don’t have the complete, the complete picture.

But if you do want to and if you want to buy and to use cloth that is genuinely made in Africa here’s Dolapo’s advice: try to educate yourself about which brands are genuinely made in Africa because this is important.

You’re constantly working against what’s, what’s accepted as being the right price and the right quality and people don’t understand why they should pay so much for the fabric. But for me, it’s still important to try because it’s sort of simple economics. These are people’s jobs and people’s lives. I’ve visited some of these factories. These are some of the people, I’ve seen them working. So for me, it’s really powerful because it’s jobs, it’s employment. It feeds into being able to educate your child if you know, so for me, that’s still very important, especially because a lot of these countries are not that strong economically. It’s, it’s a tiny little is my own tiny little contribution to, towards the kind of people that I grew up with and know deserve, you know, something of the best quality of life.

Thanks to Dolapo James and Jessica Hemmings for their help in untangling part of this story. If you would like to find out more about them or about wax cloth then you can find resources and links on the page for this episode at www.HapticandHue.com/series-three

Thanks too to Bill Taylor of the Lark Rise Partnership who produced this episode, and lastly to all those listeners who helped to make this third series possible by supporting it via the Buy Me a Coffee button on our website.

Next time we will be in France unwrapping an astonishingly beautiful scarf that was woven in Art Noveau style for a French couture house in the early 20th century. It opens a door for us to understand a little more about the people who were at the heart of one great centres of silk weaving for hundreds of years. Join me next time to hear more, and meanwhile thanks for listening.