With thanks to Janet Phillips for sharing her reflections and her life with us.

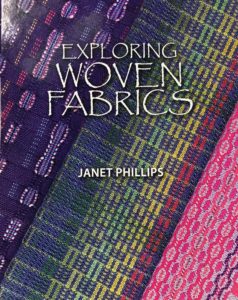

You can order her new book, Exploring Woven Fabrics, on her website: https://www.janetphillips-weaving.co.uk/ where you can see more of her work, and book courses with her for next year.

She is also on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/janetphillipsweaver/

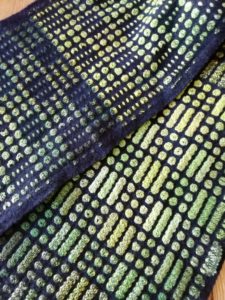

Diatom, from Exploring Woven Fabrics

Pink Wings, Janet Phillips

Lakeland Landscape, from Exploring Woven Fabrics

Script

A Weaver’s Tale

How many of us have grown our skills in embroidery, sewing or knitting, and thought in an idle moment, wouldn’t it be wonderful if I could earn my living doing this? It’s a question everyone who makes things faces: I love this, but how could I make it feed myself and my family?

Welcome to Haptic and Hue’s first series of podcasts, which looks at textiles and cloth of all kinds down the centuries and thinks about the often, hidden hands that make them and the role they play in our lives. I’m Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver and a broadcaster. And before you ask: Haptic means the feel of something and Hue describes the pure spectrum colours.

Janet: “A craftsman they say, has to be a master of their materials 48.12 and master of their tools, you mustn’t let the tools or the materials rule you and then you will produce individual things that are beautiful that will work and that people will want in their homes.”

That’s Janet Phillips, the well-known teacher and weaver, who is marking 50 years at the loom, half a century in which, one way or another, she has successfully earnt her living as a handweaver, that’s a remarkable achievement in an age of mechanisation when fabric can cost pennies to produce.

Janet: What I try and do is work on solid design principles, so I’ve had clients who have come and asked me to weave things, in colours for instance that I completely dislike, and I think how am I ever going to do this? But I follow clear design principles and it is well woven and invariably I end up liking the piece afterwards. And it’s because it’s been well designed the proportions are good, the structures are interesting. It will work.

Janet, affectionately known by her students as the Queen of Structure – is publishing a much-awaited new book this autumn. In her life, she has taught hundreds of students and reached thousands more through her books. Her career reminds all of us – whatever we make – that earning a living can be done, even in an industry that has undergone several dramatic revolutions in the past decades.

This podcast looks at how Janet has done it, and what lessons makers – whatever their materials – can draw from her practice. It thinks about what sets her, and other designer-makers, apart from those of us who practice craft entirely for our own enjoyment. And it asks what do we need to do to make items that are original, beautiful, and functional, rather than the same as everyone else’s?

Janet’s story begins in Scotland in 1968 with a chance outing for a teenage girl who was, by her own admission, picky about her clothes.

Janet: It was a fluke in a way. My grandparents came to stay one summer and we went on a day trip out from Edinburgh and we went to Galashiels and we visited the mill of Bernat Klein, who was in the late ’60s really revolutionises the Scottish tweed industry, and I just found his mill so exciting, there was so much colour and so many wonderful fabrics and this notion in your head that maybe you could earn your living doing this, this was just a 16-year-old thinking whoah! 36;00 I didn’t know this existed or that all of these fabrics that I had been so fussy about, I hadn’t contemplated how they were made, or that I could make them. And next door to Bernat Klein’s mill was the Scottish College of Textiles, so I decided I wanted to go there.

And if you don’t know Bernat Klein’s work, look him up, his use of colour and his willingness to push the boundaries of what was possible resulted in some of the most iconic high fashion ‘tweeds’ of the 1960s and 70s, fabrics that decorated almost every catwalk of the day. His work led Janet to enroll on a four-year course in weaving, and from the first time she sat at a loom she knew she had found her path in life:

Janet: I loved it, I just loved it, I loved every single second of it. And its like everything when you know what you are doing, it’s not difficult, its either up or down its either showing or not showing, it’s not actually complex.

There was no question in Janet’s mind that she was being trained as a professional weaver:

Janet: You have got to realise I was entering an industry, there was no question for my parents that this was a trivial thing to do, I was going to work, I was being trained to work in a mill to design fabrics. I wasn’t going down the handwoven route here.

But it didn’t turn out like that when she graduated there were no jobs, so rather than her expected career in a Mill in Scotland, she found herself on the train to London with a job designing coating and suiting fabrics for one of the fashionable women’s wear chains. For a young woman in her very early twenties, it wasn’t easy.

Janet: You are straight out of college, you don’t what you ambition is going to be ever. It was difficult for me, I’ve always looked very young, its in my genes, and when I was 22 coming out of Galashiels I looked like a 12 year old. I’m very small, I’m petite and who knows what it was, but I used to have to wear an awful lot of makeup, so that I might look like I was 14, and I was dealing with Mill owners in Yorkshire and it was difficult, I couldn’t do it, I was too young.

She stayed three years and learnt a lot, but industry wasn’t the right place for her so she bought herself a 16 harness loom and set up as a commission weaver working from home:

Janet Phillips: I was married by this time, so I had a shared income, I happened to be living in Henley on Thames in South Oxfordshire so I was living in an area of the country where people appreciated beautiful things and they maybe had a bit of spare money. There were also no other weavers doing it. There was almost no competition. So you weave something you go to a craft fair, you get an order, they tell their friends, and you get another order, it just happened.

She makes it sound easy, but Janet’s training means she brings a professional eye to her work, which sets her apart from many of us who weave for pleasure and maybe hope to sell some of it on the side. It was no mistake that in these early years as a commission weaver she made rugs – an item that people understand is often handmade and which crucially they are prepared to pay money for:

Janet: I need a design brief, I need to know what I am weaving for, I need to know what its end use is, where it’s going to live, whose going to be using it, and that then gives you so many answers. It will tell you what quality of yarn you may need to buy. It will certainly tell you what colours you might want to use and so, I need a brief – I need to know what it’s for. Virtually everything you look at, maybe it’s just me, maybe I just see weaves in everything I look at – that’s how my brain works as I have been doing it so long, but I can see a shape in something, I just look at something and I can see a shape and once you can see a shape, you can design it, you can weave it, because weaving is really just two shapes, a black and white picture, and the black areas are one quality of weave and the white areas are another quality of weave. It always has to be a bit stylised with weaving because at the end of the day, all you can do is stripes and checks actually. But once I can see it in my mind then I’m off really.

It’s this approach, combined with a lifetime’s understanding of the structures underlying cloth and a passion that her pupils should be able to make original, functional fabric that makes her a rigorous and gifted teacher.

Janet: when my children were very young in Oxford, there was a community education class that had been running since before the war, it had this sort of portacabin which had about 50 looms in it and the lady who had been teaching it stopped and they were looking for someone who could teach those classes. And it suited me very well, my youngest daughter was about 3, so she was still at home, so every Thursday morning and every Thursday evening I taught a community Education class in Oxford. There were 18 students in the morning and 18 students in the evening and we had a wonderful time.

She did that until all community education classes were stopped twenty years ago, then she began teaching at home, commission weaving and, crucially, writing. Janet had published a book in the early 1980s, which had done reasonably well, but her book, Designing Woven Fabrics, published 12 years ago, has now sold several thousand copies – an achievement for a weaving book! It was a departure, not just for her, but for weaving textbooks as a whole.

Many weaving instruction books work like cookery books, do this and do that and you will produce a dish that pretty much looks like this. And for most of us this is enough, it’s a joy to be able to reproduce a good cloth, even if we don’t quite understand how this has come about. Janet wants something more for her students and for the wider weaving community:

Janet: “So many books describe weaving in terms of what the loom can do, in terms of threadings and liftings, but I like the weaver to be in control, not the loom to be in control. And then you have that step back and look at ends and picks. So in Designing Woven Fabrics, I constructed a multiple section sample blanket that allows you to explore a weave structure on the loom. It’s the way I design and the way I have always designed

And it’s the process of sampling on a multi-section blanket, which is key both to Janet’s own weaving practice and to her teaching. It’s what sets a designer apart from a practitioner who follows a recipe someone else has created and thought through. What Janet is doing in her books is encouraging us all to be designers of our own cloth, writers of our own stories.

Janet: You can very well start from a recipe but once you have your recipe as you do when you are cooking if you don’t have the right ingredients you might change it for something else, or you might burn it one day and find that that made a much more tasty meal. So it’s all about taking something that is classic and developing it, breaking all the rules if you like, that the book, my book is telling you. But you can break rules if you are prepared to sample, to have a play, to explore.” So I would take a pattern from a book, take the lifting sequence, and the threading, but while I am sampling it I will have maybe five of six other possible threading plans, or colour proportions, or yarn types adjacent to it. So you can start weaving with the pattern in the book…but while you are weaving you can say why don’t I change the order in which I do these liftings, so you do a little section of that. So then you think, why don’t I make that pick that’s weaving plain weave, green instead of blue and you weave another bit. And then you will find that very attractive patterns are coming up, sometimes the pattern is absolutely awful. But this is a sampler, that doesn’t matter. You will also find out that all the other sections that you were weaving on will come up with sections that you were never, ever able to contemplate. So you suddenly get patterns that relate to each other adjacent to each other. So you are not just weaving one idea, you can actually weave several patterns on the same loom, with the same number of shafts and the same number of liftings.

Most people who are skilled at a craft, particularly weavers, get upset about mistakes and feel it reflects badly on their skills, but what Janet is saying here is that to discover new weaves and designs that you like, you have to abandon set ideas and experiment.

Janet It’s been enormously enjoyable because it’s just exploration it’s exciting, the sampling bit is exciting because you can’t go wrong if you are sampling, you can’t make a mistake, the only mistake you can make is not to try something. Once you get it onto the loom and are weaving a finished product then that’s a different mindset. You’ve got to weave this cloth that you have planned and it’s got to be accurate, but not in the sampling stage. The messier the sampler, the more mistakes you make……You have to record what you are doing, of course, you’ve got to know how these cloths are produced. People who feel they are very new to weaving come up with 150 patterns, so simply, so easily. And they know exactly how each pattern is made so they are immediately in a position where they think, I can do something that is unique to me.”

Janet spent 8 years sampling on a four-shaft loom to produce the weaves for ‘Designing Woven Fabrics’. Her new book, which has just been published, is called ‘Exploring Woven Fabrics, and yes, it has taken her another 8 years sampling, this time on an eight-shaft loom, to produce the designs for this book.

Janet: As long as you can put on a warp on, thread a loom and get it going, you will be able to weave all the sample blankets that I am giving you, there are very specific instructions on how to thread and how to weave it. Once it’s on the loom you can do what you like. And you will hopefully think of different ways to explore my sample blankets. It’s not prescriptive, we are not saying, I have discovered everything there’s a lot more every weaver can discover from my sample blankets.

Janet has reached an age where she wants to pass on what she knows. Unlike many makers who guard their hard-won knowledge, she wants to share it: the books are part of that effort, but the work that has gone into them has also informed her own practice.

Janet: After I get these sample blankets, I wash them of course so that they shrink, I spend a lot of time just looking at them. I looked and I saw this and I thought, that’s quite nice – it seems to have two very different qualities about it. That’s an interesting combination and I immediately say oh if I had the warp in that colour and the weft in that colour that would be interesting. This is a crossing that is turning up, this is not weaving a section that I was dreaming of this is something that is coming by accident on the loom, and I will think oh that’s nice and again I will weave a sample, put it onto a table loom and use different colours. Never put a single sample on, always put a multi-section sample blanket on, you might as well try it with a different colour, you might as well try it with different yarns, you just put on anything, it doesn’t matter, and then you start weaving it. And here it is, after weaving it I created this cloth. It’s small changes, and that’s one thing I have learnt in my life of weaving is that a minor change makes a big difference, which again is why you sample and you do these multiple section sample blankets, it’s because a minor change will make a huge difference. It’s the choice of yarn and sett that will make it a functional cloth.

And more than that, after 50 years in front of a loom she has an ability to marry structure and colour in a way that is producing a startling array of original work and a series of fresh designs, in which she is extending the vocabulary of weaving. This is not a matter of greater complexity, better machines that create more intricate work, instead it’s a focus on simplicity and a willingness to perfect that work which goes far beyond anything most of us attempt.

There’s also a sense in which Janet as a maker is only just getting into her stride as she approaches her 70s.

Janet: There is one other book in me and again writing a book and passing on my knowledge does seem to be an important aspect of my weaving at the moment. I have so many ideas in my head and don’t think I have got enough time in my life to make them happen or to see them. I still find it fascinating so hopefully, I’ll keep going,

JA until your nineties?

Janet: I’m looking forward to that.

This episode of Haptic and Hue was written, narrated and edited by me, Jo Andrews. Many thanks to Janet Phillips for sharing her life as a weaver with us. You can find show-notes at hapticandhue.com/listen, where I provide a complete transcript of this podcast, a list of resources and background reading that you might enjoy, and a link to order Janet’s new book. You will also find blogs and other information about Haptic and Hue there and a form to enable you to get these podcasts directly into your inbox.

Next time we are off to Paris, yes really. I went there just before the first lockdowns were introduced in Europe in the Spring in what proved to be the last days of our old lives before you know what changed everything. French Haute Couture with its extraordinary creations and its role in leading global fashion has been with us for over 200 years.

In the next podcast it’s not the frocks, the catwalks, the supermodels or the even the undoubted environmental costs of this big business that I will be focusing on, but instead the hidden hands and that lie behind the industry: the embroiderers, weavers, seamtresses, hat makers, lace makers, and pattern cutters, whose skills make it all possible.

Come with me to the streets of Paris and find out more next time. And thanks for listening.