Second Season: Episode #15

A Feeling of Wealth

This episode looks at why and how cloth and money have been inextricably linked throughout history. Cloth and money go hand in hand as much as bread and honey. This podcast unravels the story of how the consumer society and the capitalist system began, largely, with cloth trading. It looks at the times in which cloth itself has become a currency and uncovers some surprising links between textiles and banking that many have forgotten.

Virginia Postrel’s book, The Fabric of Civilisation was the principal inspiration for this podcast. It should be found at https://uk.bookshop.org/lists/haptic-hue-booklist, although they have been waiting for new stocks to come in, in which case all good online booksellers have got copies.

Other Books that I found helpful and/or interesting.

The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance, Paul Strathern

The House of Medici: Its Rise and Fall – Christopher Hibbert.

Medici Money: Banking, Metaphysics and Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence: Tim Parks

Jakob Fugger The Rich. Jacob Strieder

And just in case you are really interested, the Fugger Family has its own website which tells you a good deal about them. https://www.fugger.de/en/home.html

To sign up for your own link to the Haptic and Hue podcasts as they are released, for extra information and a chance to access the free textile gifts we offer with each podcast in this series, then please fill out the very brief form here. If you are interested in a long read or two or want to know why and how cloth speaks to us then you can find articles at www.hapticandhue.com/read

If you are interested in books on cloth and textiles, generally Elementum which is a small independent shop in Dorset specialising in Nature and Story, has a curated Haptic and Hue list where you can view and purchase a number of books. If you would like Elementum to post any of these books outside the UK then please contact Jay Amstrong at jay@elementumjournal.com

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Virginia Postrel

The Fabric of Civilisation

Florence: Built on Wool Foundations

Botticelli’s Venus, Botticelli was backed by the Medici

Botticelli’s Prima Vera

The Sistine Chapel in Rome painted by Michaelangelo

Michaelangelo’s David

The World’s Most Famous Painting – Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa

The Face of Venus, Botticelli

Not Beautiful but Rich, Jacob the Rich

The Fugger Family, Augsberg

The Fuggerei, Augsberg

Lehman Brothers Alabama Store

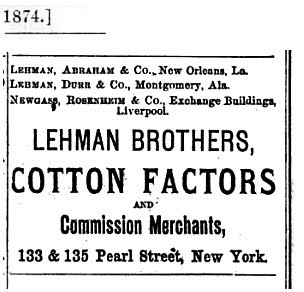

Lehman Bros, Cotton Traders

The End of Lehman Brothers

Sewbot

Sewbots

A Feeling of Wealth Script

Many of understand that textiles and working with them bring us a sort of wealth – a spiritual wealth – and that’s a privilege if we can pursue this as a thoughtful art, craft, hobby, or profession.

But down the centuries, cloth and money have gone hand in hand. As fabric production has developed, as methods and techniques of working with textiles have been invented, new systems of exchange have grown up alongside them, to allow them to be traded and to enable families and communities to turn cloth into wealth.

So this episode of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles is about actual dosh, the greenbacks, the moolah and the spondulicks tied up in fabric, right from that moment in the Neolithic when a bright human being rolled some old plant stems together and discovered string or yarn, to today – when we live in an age of plenty:

And so we take them for granted. We don’t think about where they come from. Obviously, if you go back before the industrial revolution, just simply clothing yourself, or having basic blankets or curtains or things like that was an enormous household activity. And so everybody had to think about textiles in the same way that everybody had to think about where food came from. We have textile amnesia because we enjoy textile abundance. So I want to say this amnesia is unfortunate and it blinds us to important things in history and makes us take for granted tremendous amounts of work and ingenuity that take place today. But it’s also a wonderful thing because it’s a product of textiles being abundant, and that is a recent development in human history and is a wonderful thing.

Welcome to the second series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews, a handweaver interested in how all kinds of cloth speaks to us and the impact it has on our lives. Each of the episodes in this series takes an emotion and unravels how we express that in textiles. This episode is about a Feeling of Wealth and it looks at something most societies have forgotten, which is that wealth and textiles are inextricably linked throughout human history in good and bad ways. It’s not too grand a claim to say that much of the system we call ‘capitalism’ is based on processes and systems that first grew out of the need to make and then to trade cloth over long distances.

It’s interesting because textiles are made pretty much everywhere and yet they are one of the earliest traded goods. And the reason seems to be a combination of, of the inherent division of labor in producing textiles, that is, this is it’s a process of with many stages and while they can be done, even within the same household, that’s not necessarily the most productive way to do it. And then that leads to them being done in different, possibly in different places, because some places are better for raising sheep or growing flax. And other places of the people might have particularly good skills at dying or at even weaving or spinning. So the fabric is easily transported and it’s fairly easy to understand. So you’ve got, you’ve got this easily transported, good, you’ve got fibers and dyestuffs that are agricultural products that do better or worse in different climates or different soils. And you also have particular skills, particularly in, in weaving, although other things as well, that develop in particular communities. So you have this whole history of specialization and the division of labor, and that’s what motivates trade.

Virginia Postrell, is a textile scholar and a financial journalist. She says that the story of humanity IS the story of textiles. Textiles touch everyone. Dig down far enough and you find that textile businesses funded the Italian Renaissance and the Mughal Empire, the quest for fabrics and dyes have drawn sailors across seas, they were a substantial element of the Spanish conquest in the Americas and British colonisation of India. More than any other traded good, textiles paved the economic and cultural crossroads of the ancient world as the Minoans exported wool to Egypt and the Romans frantically sought out Chinese silks. Our earliest records of long-distance trade are Cuneiform tablets around 4,000 years old that have come down to us from an Anatolian cave. They record letters backwards and forwards from one end of an ancient trade route to the other, in this case from close to Mosul in Iraq to Kanesh in Anatolia, and they reveal something surprising.

I think it would be fair to say that trade drives literacy because traders who were engaged in long-distance trade, they need to send instructions. They need to tell people that they’re trading with what to do, or their agents what to do, and they need to make contracts and agreements. And all of that requires literacy. And you can do that with scribes, but in the case of these traders in Mesopotamia, they were trading from a place called a Soar, which is near Mosul in modern-day, Iraq to a place called Kanesh, which is in What is now Turkey – it was about 900 miles, it’s a long-distance trade. And so they needed to send instructions back and forth. And they developed mass literacy and, and cuneiform tablets, which we have many of traditionally were written by scribes. And it was a very elaborate form of language, but these merchants simplified it. They made it easier to read and write, and it became a much more widespread ability reading and writing. Most of the men could read and write and a very large portion of the women could read and write. And that was important because the women were back at home base and they were the ones who were producing the cloth. And they were also the ones who were finding people to transport it to their husbands or other relatives, business partners who were basically ex-pats in this, in this town of Kanesh conducting business. So we have these letters many of them written by women that are about textiles.

We know these tablets were written by the women themselves as each rendition of the cuneiform script is individual.

Now I cannot pretend to be an expert reading cuneiform but they’re written in different handwritings that are distinctive, and you can tell, and the process by which they were produced, and they are much simpler than the ones that were written by scribes. The language is simpler and the merchants developed a way because they didn’t want to have to use a scribe. You didn’t always have one available, and you didn’t always want the scribes to know your business. So they did develop this, this sort of mass literacy.

Virginia has just finished a book called The Fabric of Civilisation in which she tells the story of how fabrics and cloth have driven immense human innovation, from the discovery of how to create silk thread in China thousands of years ago, to the invention of new chemical dyes in the 19th century, which produced a sensation amongst consumers, as suddenly they could have clothing and furnishings in bright permanent colours.

But what crystallized it all was this idea that through textiles, you could tell a lot of really important stories about history. You could tell stories about economics, about science and technology, about trade, about international relations and patterns of immigration and, and deportation. And just that through because textiles are so ubiquitous and so important. And until very recently consumed a huge amount of household budgets they are a way into the human story that opens up all kinds of fascinating areas of exploration.

What fascinates me about the tales she tells are the processes and the human skills that grow up alongside the cloth itself: female literacy in Mesopotamia is just one example, but double-entry book-keeping, bills of exchange, merchant banking, brokers, and joint-stock companies – the very pillars of the capitalist system all have their origins principally in the world of cloth.

Oh, definitely. Definitely. it’s not the only good that’s traded, but textile businesses are the earliest businesses that we find in Europe that are, you know, what we might label capitalist. They are the ones that develop systems of partnerships and later corporations and develop banking all of these kinds of essential institutions and, and even the joint-stock companies like the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company, and the French East India Company, all these East India companies they traded in many goods, but textiles were a huge part of their trade.

And what makes cloth the very foundation stone of our financial systems and our interconnected world seems to me to be two things, first of all, fabric is complex to produce, and secondly, compared to pottery or foodstuffs it’s much easier to trade it over very long distances.

So the texiles are traded goods. That’s what, it’s the same story as the literacy it’s because textiles and to some degree, dyestuffs also are very, very important traded goods. And when I say textiles, I don’t always mean finished cloth. That could be the wool or the silk threat, or it could be the wool or the raw wool or, or different stages of production. Textiles are so important in trade throughout the world that naturally enough, various social institutions, economic institutions arise from those trading needs. So, in Europe, you have ways of exchanging money without actually transferring coins. And so, you develop these paper bills of exchange, and in China, they developed something similar, which was called flying money. The term translates, flying money ways of conducting trade around guys from textiles. For the simple reason that textiles are one of the most important traded goods.

The Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman says economics isn’t a set of answers but just a way of understanding the world. He believes the so-called ‘dismal science’ really only has two rules: the first is that twenty dollars doesn’t lie around in the street for long – meaning that if someone can spot a way to make money they are going to take it, and secondly: to sell something you need to find someone to buy it. Hold onto that idea

Well, part of it, I mean, it has to do with the history of Europe. I mean, is it that textiles were a very important traded goods in Europe where you had wool out of England, which was then sold often at fairs in places like Champagne to Italians, who would take it back to Italy, where it would be finished and turned into these lovely textiles, which then would be sold in various places. So I have a lot of textiles moving around Europe and the money being exchanged originally in physical like Champagne. But then people start to say, well, why do we have to all go to this fair? Couldn’t we trade directly? Couldn’t we just, instead of taking the wool from, you know, from England to France and then down to Italy, couldn’t we just take it from England to Italy. And then that develops a need for moving the money around also because you’re not all in the same place with your money.

Now if I was going to hold a textile fair – Champagne would definitely be my top location. Sure, it was convenient, but how many bottles of the bubbly stuff got drunk or went home to England and Italy in the cloth packs? No wonder we have a taste for it. But the difficulty here in the 12 and 13 hundreds, as this trading system was being developed, was money, pounds, francs, florins, guilders:

So essentially you have this problem. The problem is money is heavy and subject to robbery. So you’re talking about a world in which money is gold and silver and hauling it around Europe over the Alps, going back before, or even around England is burdensome and dangerous because you could be set on by highwaymen. And so the question is, is there a way that you can transfer your money without actually carrying around precious coins?

The answer was bills of exchange, which are the first forms of cheques and paper substitute money. That means that, sadly, you don’t need to trek off to Champagne with a lot of gold and haul home a lot of cloth, or vice versa. Instead, if you are a British silk buyer, called, let us say, Peter, and you want some Italian silk, you get a bill of exchange from your British bank saying this is worth 1,000 florins to my valued contact, Piero in Florence. That goes off safely by fast horseback messenger, Piero sends the silk off to Peter, and then he gets his money by presenting his paper Bill of Exchange to his bank in Florence. We can see how a system of international banking and the much-needed systems of trust and confidence begin to build up – all from the need to move cloth around. Cloth making is a long process, even today, as we heard in a previous episode in this series – A Feeling of Warmth, but in early medieval times everything had to be done by hand:

There are so many steps in the textile production process that can be divided up over time and space. So, you’ve got an, and there’s a long period from the time you say, raise the sheep to the time you have a finished, beautifully dyed piece of wool and cloth, and each of those stages requires working capital. You need the money to do the job before the ultimate pay. So, you develop lots of financial institutions along the way also to facilitate that.

So alongside the new banking processes, the clothiers, the cloth dealers themselves became lenders of capital to farmers, spinners, dyers, weavers, and finishers, and as they have good reputations and everyone knows they have actual cash, they begin to write the bills of exchange, and so step by step the clothiers become bankers. These are the people who bankrolled the opulence of the Renaissance and most of the Royal houses of Europe.

Certainly by the, you know, by the 14th 15th century, you’ve got all these banks around Europe and particularly in Italy, but not exclusively that started with the textile trade. But the great, the great banking empire that starts in the textile trade is at Fuggers of Ausberg. And they start in the textile business in the 15th century, but they start lending out money. And then they, they would lend money to princes of which there were many, and, and the Princes had a very bad habit of defaulting on their loans. So then the Fuggers would collect mines that the princess owned as there would be often that was often the collateral. So then they became a mining empire, which helped their banking empire as well. So they became the richest people in Europe, and they had started as weavers. So the textiles basically provided the initial capital that then got them into lending out money. Then they built a banking empire. You know, there are other people like the [inaudible] who are bankers primarily, but lending to the textile business, but they didn’t actually start in the textile business. They, they had some textile interests, but that wasn’t the, but the Fuggers started as a textile business.

Augsberg is in Bavaria in southern Germany and Jacob Fugger – the founder of this banking dynasty was the son of a weaver, but he became probably the richest man Europe has ever seen. When he died in 1525 his fortune was equivalent to 2% of European’s entire production, far larger, comparatively, than any of the tech fortunes we see today. This was wealth beyond imagination. He helped to trigger the Reformation and is thought to have funded Magellan’s voyage around the world. He was the man who was the money behind the rise of the Hapsburgs and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He’s not the only one, the world’s oldest merchant bank, still functioning today is Berenbergs in Hamburg, who were originally cloth traders, the Baring family in Britain started life as Exeter wool merchants before they abandoned that for merchant banking. And then there are the Medicis who are in a class all of their own. In the early 1400s, we find them as wool traders in Tuscany before they worked their way up the ladder to became bankers, popes, princes, and queens. It was wool that took the leading family of 15th and 16th century Europe to the top. This was the family and this was the money that funded the Renaissance in Florence through their support for Leonardo da Vinci, Michaelangelo, Botticelli, Raphael, Machiavelli, and Galileo. They claim too to have funded the invention of the Piano and opera as well. And so it goes on, all over Europe as those in the complex trade of textiles transferred over to banking, from Lombardy to Norway from Lisbon to Istanbul. And let’s not leave out the US where Lehman Brothers – the great casualty of the 2008 crash – began in a little shop in Alabama.

They started just as many Jewish immigrants who came to the United States started they had a little general store and in a town in Alabama, this was before the Civil War. But from that store, they developed as many other people did into lending money first, you know, they would lend people money to buy the goods in their store because it’s an agricultural region. And you only get paid when you harvest your cotton and you sell your cotton. And then from that, they started, Oh, well, we could lend money against the cotton, not just for buying groceries in the store, but we could essentially be bankers a kind of financial institution. And so they, they became cotton brokers. They, they would, they would say, you know, here’s money that is lent against your cotton harvest. And instead of interest, we’ll take X percentage of the cotton harvest. I, they may have charged interest to it, but I, but essentially they, they came into possession of not just interest financial money, but they also came into possession of a lot of cotton, which then they would broker in New York and, and where it would then go to Manchester.

And from Cotton they progressed to other sectors.

They finance railroads and they finance the big department store chains. You know, like Sears and Macy’s that developed in the 19th century. And, and they finance some of the early computer businesses. And, you know, so every kind of I’d steal every kind of major business that was part of the development of, of the United States economy. They had a piece of it they’re not the most important. And then of course they became in 2008 when they collapsed. And that’s where the story of Lehmann brothers ends. But they started with this problem, which is in their case a cotton problem. But as one that in, you know, parts of England would have been a wool problem and parts of China would have had a silk problem. And the problem of you have to invest in the crop that you’re going to raise long before you’re going to get paid for it.

So think of that when you next stray into the shiny temples of finance, in New York, London, Frankfurt or Tokyo, or just pass by the Bank in your neighbourhood, or when you gaze upon a renaissance masterpiece – they are built on cloth foundations, and even though they have now forgotten it, we haven’t. But there have been other times in the past when cloth has actually been money:

This is different from bartering textiles. You know, I give you textiles and you give me wheat or whatever. These are standardized bolts, they’re standard denominations. They’re, portable, they’re divisible. They can translate into other types of currency. In some cases, in China, there was a shortage of copper coins. So in China, they were actually legal tender, this particular type, of silk bolt. You were required by the government to accept it. As currency you could pay could, in some cases were required to pay your taxes in it.

A similar system developed where cloth weavers became currency makers:

In West Africa where they traditionally make cloth by weaving narrow strips, like four to six inches wide, and then sewing them together into large claws that are worn like a to-go or a sarong. They developed a way of, they would weave specific types of strips that you would, instead of sewing it together into a large cloth, you would just roll it up. And that was your currency. That was the smaller denomination. And then a whole cloth might be the larger denomination. And this was very portable. It was easy to take around and they were understood.

And in Iceland too, a certain type of cloth became recognised as currency:

In Africa and in Iceland, it was not a top-down process: It was not the government saying this is money and you have to accept it. It was a bottom-up process. It was merchants saying, well, we’ll use this cloth as money. And then it was, it came to be recognized in legal and what you might call common law in legal dealings. So you could have contracts in it, or you could be paying fines in it, that sort of thing. But yes, cloth actually is, but in the pre-industrial world, it’s actually a very good currency. It’s hard to have inflation or deflation because it has this other use as actual cloth. So if, if, if it becomes less valuable because of essentially inflation, then people just turn it into clothes or whatever, until you get the money supply equilibrated if it, if there’s not enough of it, you weave more. And so it doesn’t have some of the problems that people had with gold and silver. And it, now once you have industrial production of cloth, this all goes out the window because it’s too easy to make. So you can have massive cloth inflation but in the pre-industrial world it is actually a very good currency..

But in all this talk of finance we are missing something important. While a section of society has got rich, sometimes incredibly rich, on cloth, millions of others have suffered and continue to suffer appalling abuses to produce the cloth that has fuelled the rise of a capitalist and consumer society, this goes right back to Egyptian, Roman and Greek times and even further back when most fabric was produced by slave labour.

And, and then there have also been, you know, various atrocities created committed in order to get textiles. And the most famous one of course is American slavery. But I write in the book about all the Mongols, bringing people from Afghanistan all the way into Northwest what is now Northwest China. And this is actually the origins of, of what we see today with the Uighers in China, which there’s a textile dimension to that as well, which has to do with the coerced cotton cultivation.

Where Slavery exists you will usually – not always – but usually find cloth production. When slavery is abolished in each country these become paid jobs – which is progress – but jobs that are dangerous and often poorly paid. In the US and the UK and elsewhere in developed economies – these jobs have disappeared – and there is an ambivalence about this.

I remember I toured a bunch of places in Northern England, all these mill museums, and the universal message was, Oh, these were the worst, most horrible places to work. Oh, we wish they hadn’t gone away.

The difficulty here is that even though these are boring or dangerous or poorly paid jobs, and people can work in extremely bad conditions, the manufacture of textiles as an industry employs large numbers of people and has played an important role in helping different countries at different times and lots of people move out of overall poverty.

One of the important roles that the textile industry has played over and over and over again is as the early step on the sort of ladder of economic development what the great enrichment as the economic historian, Deirdre McCloskey calls it, starts with the industrial revolution, and that’s what lifts global living standards worldwide. And you often see when you have a less developed country whether it’s, you know, it’s the American South or after World War Two, or South Korea and Japan, or whether it is Taiwan or whether it is China and India and Vietnam, depending on where you are in the country’s history, but when you have these less developed countries, often producing cloth, and then cutting and sewing, turning that cloth into clothing, is the way you start to get out of poverty and, and into manufacturing economy.

Textile production has been one of the great levers to achieve a better life for people and countries for centuries. But Virginia wonders if the new age of automation will put an end to that.

Now, the question today that people are concerned about, we economists who study economic development is whether, down the road, this may become so automated that you no longer need those. You know, and we talk about sweatshops and all of these things, and they are, you know, they are bad, but they are this a very important stage in rising up. And that’s happened in recent years in China, it’s happening in Vietnam. And the question is, does that process continue? Does everybody go through that? Or do we get to a point where we have what are called, sewbots, for example, robots that, you know, sew, and you don’t need those people. And so any economic development has to take place in a different way. And if so, how does that happen?

And that’s something humanity will have to solve, but it brings me back to this: down the ages, textiles have been some of the most astonishing producers of wealth that human beings have seen, and they still are. The difficulty has not really been about creating that wealth, but instead, it’s about ensuring that the wealth is fairly distributed between those who provide their labour, compared to those who provide the capital and the machines. It’s a big ask, but would it be a wonderful thing to live in a world where the clothes we wear and the textiles we use haven’t been produced in sweatshops, like the Rana Plaza, or in fields where forced labour is being used. It’s a dream – but a dream worth having!

Thanks to Virginia for sharing a very small part of her knowledge about textiles and civilisation. If you’d like a link to Virginia’s book and other books that I found useful in putting this episode together then please go www.hapticandhue.com/listen, where you will also find a full script of this podcast and a form which gives you a chance to win the textile-related gifts I give away with each episode.

By the way, I have always loved the American word Spondulicks – it comes from ancient Greece when spondulys – or shells – were sometimes used as money. How glorious to go down to the market with a bagful of clanking, slightly sandy shells to do the shopping. It makes you look at a trip to the beach in a whole different way.

Next time we will be thinking about a feeling of belonging and how textiles give expression to our deepest emotions about who we are and how we identify who is part of our community. But I will leave you this time, at Virginia’s suggestion, with a passage from Emile Zola’s book – The Ladies Paradise – published in 1883. It’s about the rise of the first big department store in Paris, which in the beginning was principally about buying fabric, about the consumers of this stuff, who are after all the people who have driven the Felling of Wealth that has clung to textiles throughout the ages. Here is Zola describing the silk department’s display.

A veritable torrent of stuffs, a puffy sheet falling from above and spreading out down to the floor. At first stood out the light satins and tender silks, the satins à la Reine and Renaissance, with the pearly tones of spring water; light silks, transparent as crystals—Nile-green, Indian-azure, May-rose, and Danube-blue. Then came the stronger fabrics: marvellous satins, duchess silks, warm tints, rolling in great waves; and right at the bottom, as in a fountain-basin, reposed the heavy stuffs, the figured silks, the damasks, brocades, and lovely silvered silks in the midst of a deep bed of velvet of every sort—black, white, and coloured— skilfully disposed on silk and satin grounds, hollowing out with their medley of colours a still lake in which the reflex of the sky seemed to be dancing. The women, pale with desire, bent over as if to look at themselves. And before this falling cataract, they all remained standing, with the secret fear of being carried away by the irruption of such luxury, and with the irresistible desire to jump in amidst it and be lost.