Second Season: Episode #14

A Feeling of Sorrow

This podcast looks at the special place cloth plays in mourning a much-loved father, the loss of a child or partner in political repression, or how they can help us commemorate those who were victims of appalling events like the Holocaust.

The issues this episode deals with are not easy, but in one form or another, sorrowing is something all of us do at some stage in our lives, especially as we come out of a pandemic that has claimed millions around the world.

With thanks to Caren Garfen, whose stitched work on the Holocaust is enormously powerful, to Deborah Stockdale at the Centre for Conflict Textiles in Northern Ireland and to Judith Staley of Sew Over 50 for sharing the memory aprons she made to remember her Dad.

Caren’s website is at http://www.carengarfen.com/. She can also be found on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/carengarfen/

Conflict Textiles can be found at https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/conflicttextiles/ . If you would like further details of the arpilleras there is a good film on Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/243661034/26dfac47c5

Judith and Sew Over 50 can be found on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/sewover50/ And Judith herself can be found at https://www.instagram.com/judithrosalind/

To sign up for your own link to the Haptic and Hue podcasts as they are released, for extra information and a chance to access the free textile gifts we offer with each podcast in this series, then please fill out the very brief form here. If you are interested in a long read or two or want to know why and how cloth speaks to us then you can find articles at www.hapticandhue.com/read

If you are interested in books on cloth and textiles, Elementum which is a small independent shop in Dorset specialising in Nature and Story, has a curated Haptic and Hue list where you can view and purchase a number of books. If you would like Elementum to post any of these books outside the UK then please contact Jay Amstrong at jay@elementumjournal.com

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Judith’s sisters enjoying the aprons

Vern Staley – with one of his shirt collection

Judith Staley – apron maker and founder of Sew Over 50

|

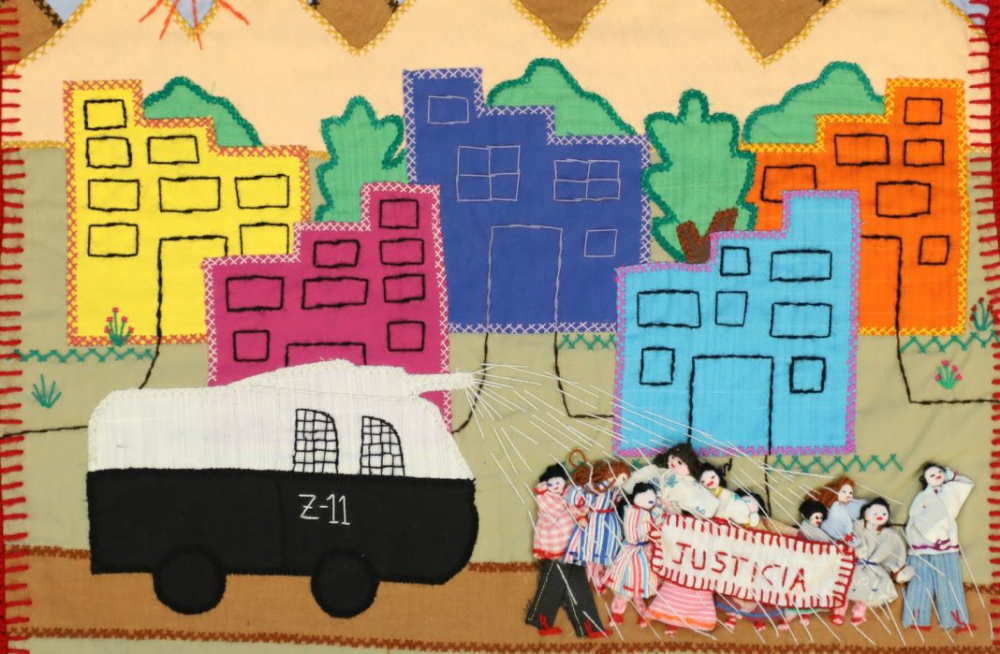

Puntadas de Vida / Stitches of Life Argentinean arpillera, Ana Zlatkes, 2015 Photo Ana Zlatkes, © Conflict Textiles |

|

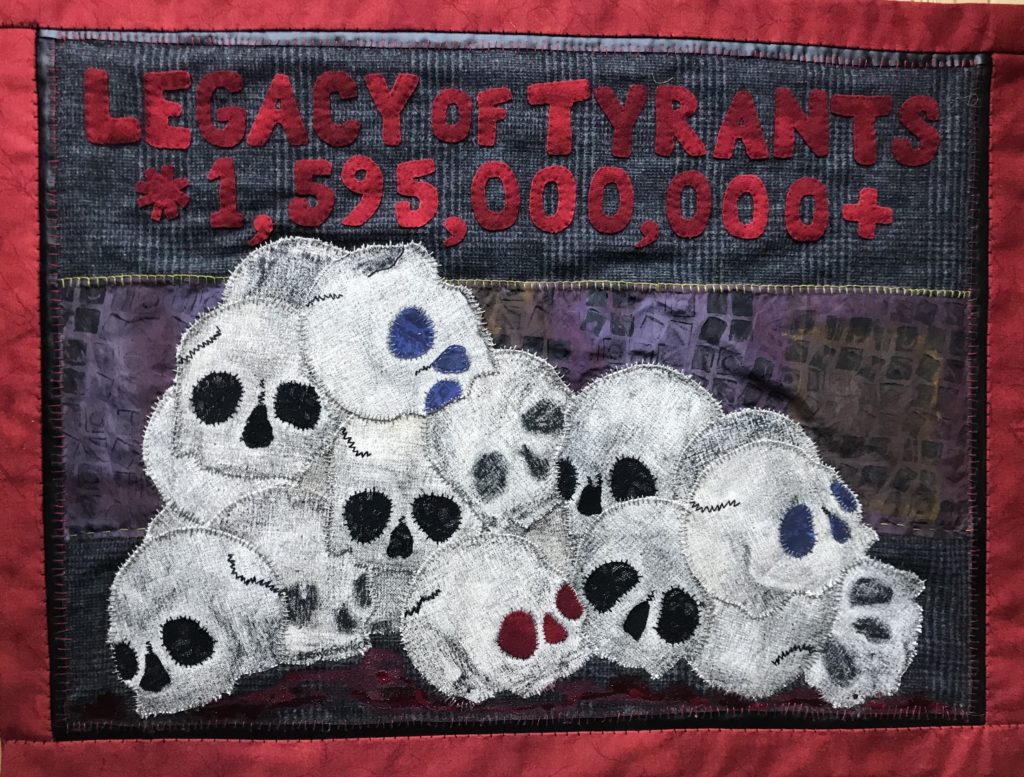

Legacy of Tyrants / El legado de los tiranos USA arpillera, Lisa Raye Garlock, 2018 Photo Lisa Raye Garlock, © Conflict Textiles |

|

They Fell like Stars from the Sky / Cayeron del cielo como estrellas Republic of Ireland arpillera, Deborah Stockdale, 2013 Photo Martin Melaugh, © Conflict Textiles |

Chilean Arpillera

Arpillera from the 1970s, Chile.

|

Hornos de Lonquén / Lime kilns of Lonquén Chilean arpillera, Anonymous, c1979 Photo Tony Boyle, © Conflict Textiles |

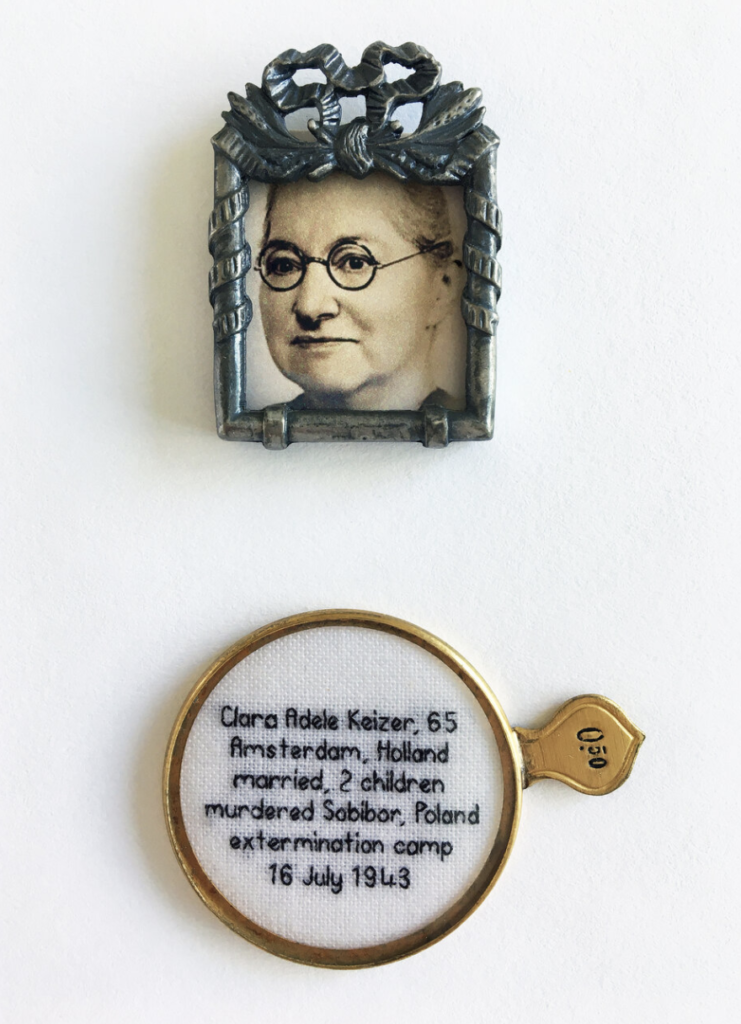

Caren Garfen

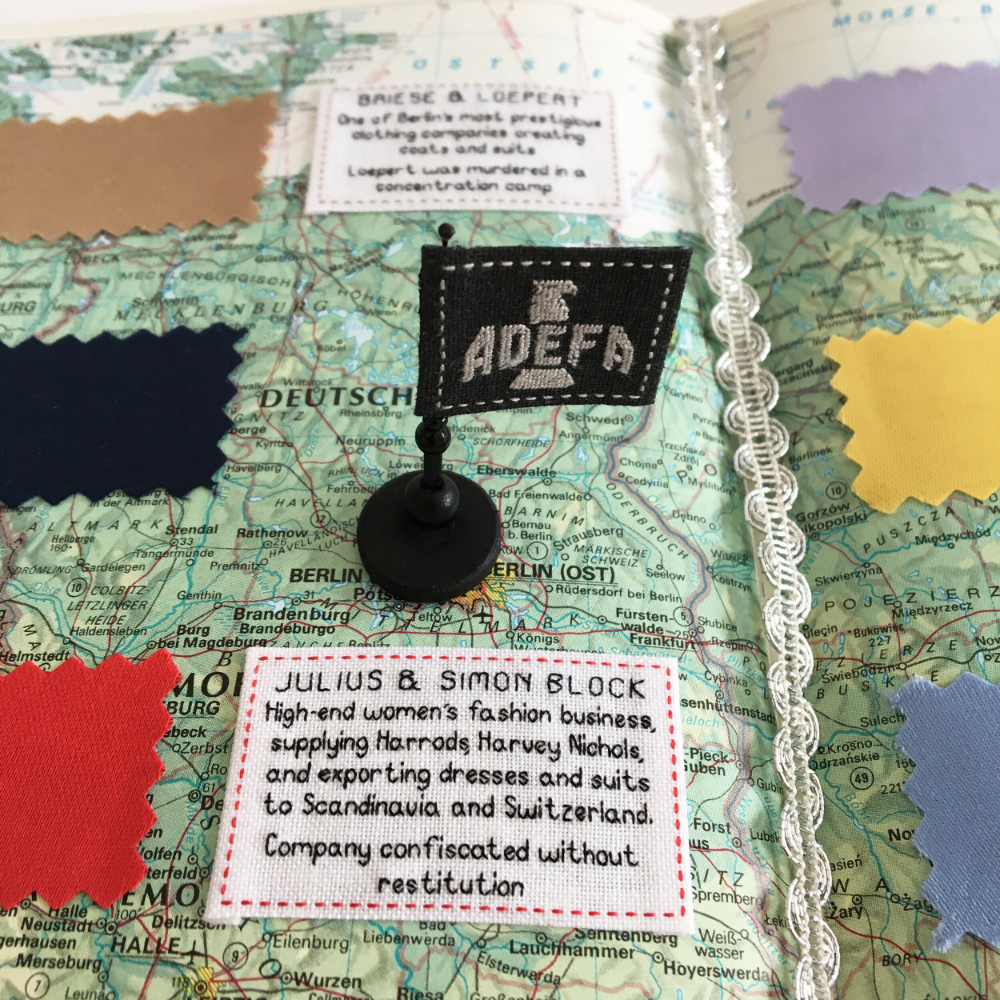

From ‘Selection’, Caren Garfen

From ‘Shattered Dreams’ Caren Garfen

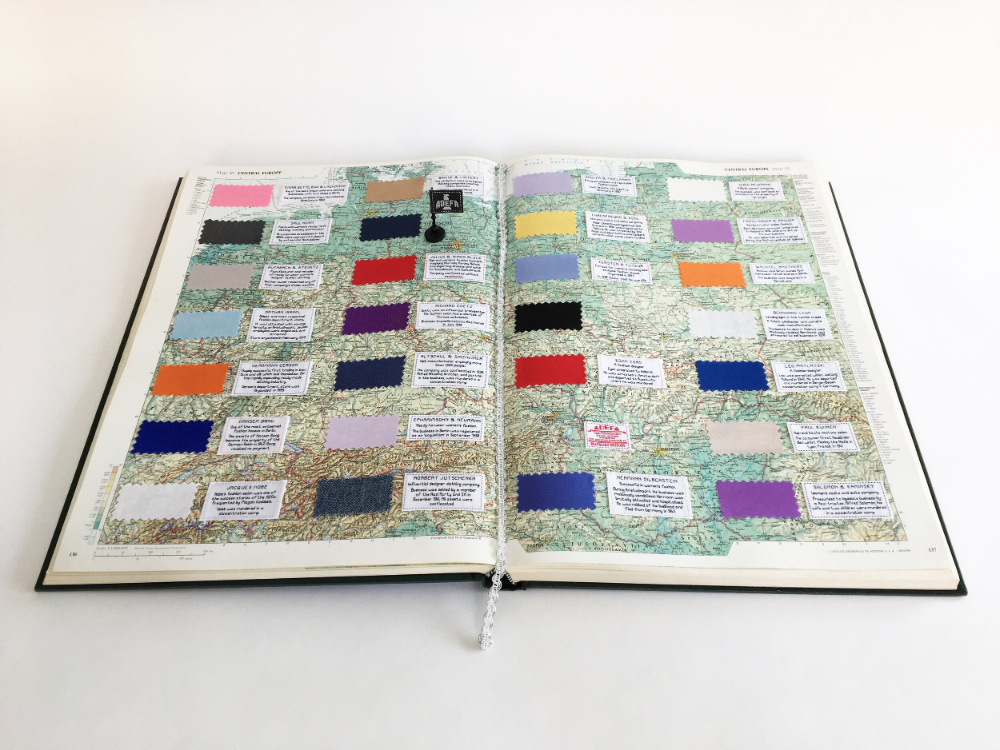

“Fragments’ Caren Garfen

“Fragments’ Caren Garfen

‘Fragments’, Caren Garfen

A Feeling of Sorrow Script

Welcome to the second series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews, a handweaver interested in how all kinds of cloth speaks to us and the impact it has on our lives.

Each of the episodes in this series takes an emotion and unravels how we express it in textiles. This episode is called a Feeling of Sorrow – and it’s about how we deal with the deep and difficult emotions that grief brings. It looks at the unrecognised and often unarticulated comfort that textiles can give us in this process. It also deals with remembering people who have lost their lives in political violence, how we commemorate huge events like the Holocaust and how we might use textiles to memorialise those lost in the pandemic.

This is not for everyone and please don’t listen if this distresses you. But sorrowing is a profound human emotion – one that we will all experience in our lives and textiles can play an important role in helping us to do this.

My father died in 2016 just before his 96th birthday. So, you know, he’d had a long life and he was, it was sad, but not, you know, not unexpected. And so I’d taken his shirts because I just thought, well, I’m the sort of keeper of everything really. I, in the family, it’s not that I like clutter. I don’t like throwing things away. So I took, I’ve kept the shirts.

That’s Judith Staley talking about her Dad, Vern. His shirts were pretty special.

We sort of bought my dad’s shirts latterly in the last 15, 20 years of his life. I suppose the one sister in particular always chose him a lovely shirt for Christmas. So it became part of him. And I think it was, he liked them because they were gifts from his daughters. And he was, he was a real family man. He is a very gentle man. He loved loved his family, loved nature, animals, children. And so I think he, the shirts were because it, he, he liked them because they were gifts from, from us, but it became very part parts of him, you know, that it was, and he had to have a top pocket to put his hearing aid in.

Judith is the founder of a remarkable movement called Sewover50, which is a gathering place for people of all backgrounds who sew and make their own clothing. I have no doubt that was it to become a political party it would take over the world. It has just celebrated its 30,000th follower. But even though Judith has all the sewing skills, it took her time to decide what she could make from the shirts for her three sisters.

And I wanted to do it as a surprise, but, but then I wanted to make sure it was something that they would, what they would want, you know? And I thought it would be nice to make some things that they could wear rather than a cushion. But again, I didn’t think making a top seemed appropriate. Somebody on Instagram had made an apron from a shirt or from a few shirts. And that just gave me the idea that I could do that for my sisters. Because it’s something that they won’t wear every, every day or out in public or whatever, but they can wear a home. And it’s sort of like wearing a part of a part of my dad.

Making the aprons brought back lots of memories of her father and helped Judith process her own feelings:

So as I was making my sisters the aprons, I, again, I was thinking, I was thinking of my father as I sewed them and, you know, pictures of him and the shirts and, and and being with him, you know, wearing the shirts, walking into the house and seeing him there.

And her sisters enjoyed the surprise.

Well I think I, my sisters all live fairly close together, down in England and they were, they did get together for Christmas day. So I’d sent a joint parcel with them in. I wanted them to open them together and luckily they were able to, and there’s a lot of humour in our family, a lot of joking. And, and so I think it was a mixture of being able to being able to laugh at themselves, but come comfort as well, you know, tears, tears of both laughter and, and sadness. And they were, you know, they really, they put them on straight away, sent to the photograph to send me and, and I think made Christmas dinner wearing them. I knew how they, how receptive they would be to it. And I knew, I knew they would be fine. They would, they would like it and the apron will pop, you know, hang them in the kitchen and they’ll catch glimpses of it and they’ll wear it sometimes, but they it’s just the catching glimpses of my dad, I suppose.

In the past many of us would have marked the death of a family member in very different ways. The Victorians, in particular, made this a highly formal and complex display with specialist fabrics and clothing worn for long periods of time. Dresses of Paramatta Silk or the cheaper Black Bombazine, veils and black armbands would be commissioned. The British textile manufacturer, Courtaulds, made a sizeable fortune just producing black mourning crepe, so widespread was the demand. Entire stores sprung up to provide appropriate dress to all family members as quickly as possible after a death – one of the most popular was Jay’s Mourning Warehouse in London. But today for many, our sorrowing is much more individual and private – there is very little expected of us in the way of dress or behaviour after a death, which leaves us with the question of how do we process sorrow? Judith thinks that working with textiles has a special power to do this and that it has a strong connection with memory and feelings.

I think it’s the touch of the fabric. The fact that the idea that, that has that the loved one has worn that close to their body and, and that’s, and then you can somehow feel them through, through that. Unfortunately, my mum died in 2012, before I began sewing again, and I didn’t keep any of her clothes. She had a thing for cardigans, I’d have loved to make something from those, but I do have an a silk jacket of hers that she bought, just after the war, I think in Bond Street and, and I wear that occasionally and I really love to wear that because, because that’s the one thing I’ve got of hers, clothes-wise, and she loved her clothes and that’s the one thing I’ve got and I, I love to wear it because she wore it. And it’s just lovely to have that, I suppose it is like having a hug, having them present on your body.

There is a sense that touch and handling fabric engages our brain in a way that gives the conscious parts of it something to do and allows deeper emotions to surface. It seems to access a different system to words or speech– a system that connects more directly to our feelings in a less formalised, calmer way. There has been a lot of research done, not least by the UK’s National Health Service on how knitting helps to deal with chronic pain, and what is sorrow if it is not a different kind of pain? But this is not the only role textiles play in sorrowing. In 1973 Chile’s democratic government was overthrown in a violent coup. A military dictatorship was established by Augusto Pinochet and thousands of people suspected of left-wing leanings were snatched off the street and disappeared. The repression was intense. Anyone who tried to say what was happening put themselves in great danger. There was complete silence until people took up their needles.

It came about as a way of mostly women in under these regimes of expressing the, the great tragedy that was unfolding in our country at the time, especially in Chile. The normal journalistic avenues were sequestered. They weren’t allowed to talk about it. You could be arrested for even having given support to a dissident or a protester. It was a way that they could call out to the world at large, their grief and sorrow and the difficulty of living under these conditions.

The textiles were called Arpilleras, which in Spanish means simply ‘burlap’, or hessian because that’s what the pictures were stitched on – a form of sacking. And as sewn materials, they passed below the radar of the state. Deborah Stockdale is a specialist in Arpilleras, she works at Conflict Textiles which is an international collection in Northern Ireland that focuses on elements of conflict and human rights abuses expressed in textiles. Deborah says the Arpilleras were made to send a message AND to express sorrow:

I think both of that is true. A lot of cases, they were making them for themselves. It was a way to deal with grief and to deal with that disappearance and to, and to hold the fabrics of the shirts and the trousers and the school uniforms. And to honour the person that would have worn these things and handle these things on a daily basis. And the difficulty with the Arpilleras is that a lot of them are very, very personal to the person. And it was a way of speaking out that they would have never been afforded as citizens. They, it was a way that they could communicate with the larger world that these things were happening and, and the way they were smuggled out to countries in Europe and other parts of the world, it was like an underground railway of information because they were so seemingly domestic and craft like they didn’t come to the authorities’ attention. And, and the authorities didn’t realize the significance of what the stories were telling to the rest of the world.

The Arpilleras were exhibited in Germany and Britain and were some of the first evidence of the repression that was spreading across Latin America and the terrible impact it was having on families. Deborah says she was immediately drawn to them:

For me, it was a combination of my love of storytelling and history and textiles, which runs side by side. The fact that they were small, miniature, very complex creations their domesticity and often prettiness or cuteness of the colorful fabrics and the small doll-like creatures belie their very complex background in history. And the story that they tell stories sometimes that are extremely difficult. We’ve talked about torture and disappearance, imprisonment, families in distress, loss. And the combination of all these things in one small, you know, 25-inch piece of fabric attracted me immensely

Deborah has been a quilt maker for 50 years and has worked with a number of community groups making historical or story-based textiles. She is no stranger to sorrow herself and has made textile pieces to commemorate the deaths of her brother and sister:

I think textiles have a language of their own. They have one of the things that I always say is they have prana. Prana is the connection between the animate world and the inanimate world. And I think the objects that we use and that we wear and are imbibed with our own energy, like old clothes, old hats, anything that’s in daily uses carries its energy onward, and it cannot exist without the person. And I, I find that when I am making a Memorial piece, like for my brother and my sister and making these Arpilleras that connect me with specific people, they have the energy from that person and by making artwork with it, I’m carrying that energy forward and displaying it for other people to see, I think that feeling of a soft old blanket, or like a scratchy Tweed coat evokes memories in us that are almost subliminal and very important. It cuts through a lot of the verbal connection that we would have with people. And I feel that by using these things, it gives them a further connection and importance in our lives.

And that sense of standing outside language means that many people have a specific reaction to the Arpilleras.

I think it depends on the person, but one of the first responses when people see Arpilleras is that they want to touch them, which is to me is a automatic connection, especially concerning textiles, the desire to touch, to feel, to use the other senses just beside the visual to connect. And I think that we all, we all desire to touch them, to feel what it’s a sense that it’s been less familiar to us in modern, the modern world. We’re all ever so slightly disconnected. And I think Arpilleras evoke this response in people. I know that, you know, as the textile artists, you aren’t really supposed to touch things that are on exhibit, as we all know. But they, they do evoke that in people they want to, they want to feel it as well, especially the three-dimensional part for the small dolls and the embellishments and people put on them.

The power of the stories Arpilleras can tell has meant that they have been adopted almost universally. Many artists and individuals have used them to convey their own feelings. In Deborah’s eyes, they can connect us with much bigger events, events which, otherwise, we find difficult to approach or understand.

One of the Arpilleras in the collection is by a woman called Anna Zlatkes, she’s an Argentinian and it portrays a man and a woman leading children out of war-torn buildings, you know, buildings that are been reduced to rubble. And it honours her piece honours, the men and women, the many men and the many women that led Jewish children to safety throughout Europe. So it’s, it’s a humble looking piece. It’s just a man and a woman on a child in a Chan, but it represents so much, it represents thousands of thousands of people and thousands of efforts and thousands of children that were saved. So in a way I think that, you know, a very small, simple artwork like that can connect you with a much greater picture.

Connecting with a much bigger picture is exactly what Caren Garfen does. Her work is powerful and moving – often all the more so for being very simple – stitched words on everyday objects. But there is nothing simple about the subjects she tackles. For many years Caren created stitched artwork about eating disorders and body dysmorphia. Here she is describing what happened when she exhibited these pieces at the big Knitting and Stitching shows in the UK and Ireland.

And people came in and the emotion and the sorrow and the fear and the relief from people was just unbelievable. First day, first morning, nobody really around am. I came into the space to just make sure everything was fine. And there was a young woman reading something on a drip. I had made her a drip bag, which was hanging from a drip stand. It was all hand-stitched. And she was reading the words on that. And she was crying really, really crying. And and I just hugged her and she said, she just said, this is me. And honestly, it was like, okay, after the first exhibition, which was four days at Alexandre palace I was just, just so drained because it was like people were crying. So many people were crying and S and, or, or they were talking, Oh, which was great.

She says she never forces her work it just comes to her – and what came to her next was a feeling that she had to tackle both the Holocaust and also the rise in modern anti-Semitism.

I said to people, my close family sisters, I said, this is what I’m going to do. And even my daughter, the same, I told, told her that I’m doing this work. And they said, don’t do it. Don’t do it because I think they were scared because for, for many years a lot of Jewish people don’t say they’re Jewish. I think it’s just, it’s just, something is sort of like a self-protection. Anyway, so I, I, I said, I’m sorry, but whatever happens, I’m going to do this. There’s something in me which says, this is the time to make the work.

Part of the power of the work she makes lies in her ability to give back individual identities to victims of the Holocaust. In one piece she selected people who wore glasses to create a cross-section of people across Europe. There is a photo of each person and then under a small spectacle lens a magnified description of what happened to them: Gita Heymanson, Riga, Latvia, Housewife, married 3 children, murdered 1943, Kaiserwald concentration camp, Riga. Hans Groenewoudt, 19, Eindhoven, Holland, Chemist, in hiding, disappeared, not heard from again.

I think you live with the burden of the story, but like I have to, as I did with the eating disorders, I had to sort set up some sort of mental barrier because otherwise it’s not my place to do week on. Well, I, I, I don’t, I don’t think it’s my place to do that. I think those people have suffered so much and it’s, it’s my job to tell the story and whether it’s painful to me, which it is I do it, I feel compelled to make the work and, and each story, excuse me. And each story is unique. There might’ve been 6 million and 6 million. It doesn’t really suggest anything to me. It’s just a number. But when you go into that and, and it’s one person I think that’s, but you realize they’ve had a life. They were happy children. And they lived with their parents in their home and they, they went to school or they worked, or, you know, they went to visit their auntie and, and, and they’re, they’ve lost everything. They’ve lost their, their whole, whole life really.

Caren’s work has contemporary meaning too, because mixed in amongst the photos of those who perished in the Holocaust are pictures of those who have been victims of modern attacks and in this way Caren draws a direct line between the Nazi era and anti-Semitism today.

So yeah, I think it’s, I think the textiles are very important because well, in the, in the Jewish religion and other religions and other cultures material is very important. It’s just part of a culture. And in, in the Jewish culture, there’s, you’re looking at, you’re looking at things like a head or a pressure or, or you’ll even looking at Challah. Challah is a sweet bread platted bread, which is eaten on a Friday night with a Friday night meal. And that’s covered with a cloth. Everything is sort of relates back to textiles, right from the very beginning, from a circumcision all the way up to death. And the actually people are treated even in death with respect and dignity with they wrapped in a very simple burial cloth, which is pain, white, plain, white, and made of linen or muslin and wrapped with care. The women will wrap the female body and treat it with utmost respect. So you’re going through a whole lifetime of textiles in the Jewish religion, but I know the burial cloth is, I think has used with Muslims as well, do that very similar thing. So it sort of is part of us. It’s part of being a human being and people are drawn , into the cloth.

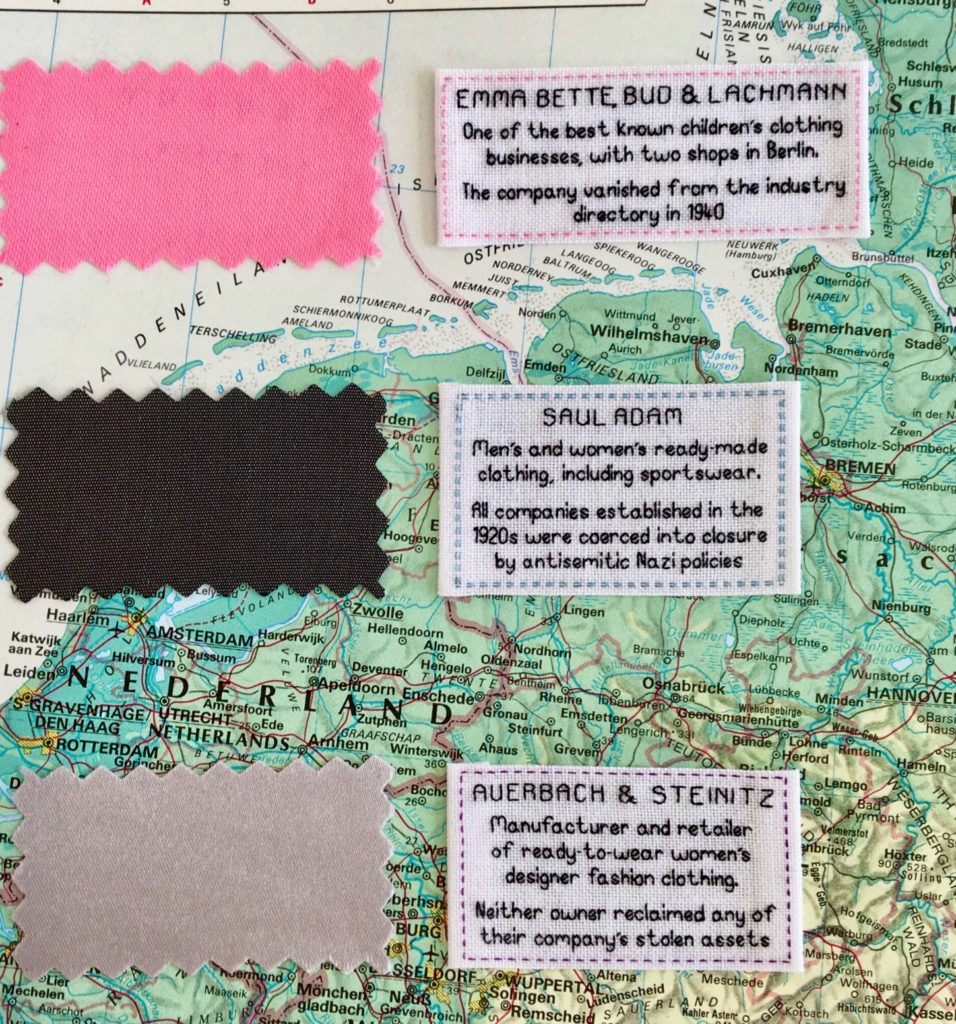

Caren also has a way of approaching the Holocaust that can help us see the outlines of the tragedy in a different way. One of her pieces – just finished – came as a submission to the British textile Biennale. The brief was to reflect on the impact of textiles on people and place through personal histories and geographies. She decided to look at the Berlin fashion industry in the 1930s, and all the companies that supplied it. At first she focused on those who escaped and built successful lives elsewhere, Bernat Klein, Jaqueline Groag and Marion Mahler, but then she changed her mind:

But then I was thinking, yes, but they are remembered. I want to look at those people that aren’t remembered or may have been remembered, but then forgotten who, who had incredible businesses, incredible talent, fashion designers and retail people people, you know, businesses that made corsets and buttons and all the things that connect to the fashion industry, they were really important to the economy of Germany and they were very talented people. And I think just under half of the population of Berlin who were in, in the fashion industry were Jewish. And, but they were working side by side with other people. They were all connected.

She wanted to create a piece that could illustrate the impact of Nazi policies on this thriving and innovative industry. Fragments is the result. At first sight it’s pages from an old fashioned atlas with little fabric swatches stuck in it:

And I mean, it was a very gradual thing because I didn’t actually have this set vision. It just happened, it evolved into this piece and I suddenly thought I’m going to make these labels because they’re the labels you would find in your own clothing. So you can relate to that. I decided to use the labels and write down the names, stitch hand stitch, the names of those people who lost their businesses or left the country. They, they escaped to the Netherlands or to France, or, and they were picked up or they were picked up when the, after the Nazis invaded those countries and they were arrested and sent to concentration camps and murdered, you know, it appears some really clever people, some really talented textile artists or textile, sorry, textile designers, and, and they’re gone, they’re lost forever.

Here are a couple of entries: Julius and Simon Block, high-end women’s fashion business supplying Harrods, Harvey Nichols, and exporting dresses and suits to Scandinavia and Switzerland – confiscated without restitution. Egon Zons – A Fashion Designer. Egon emigrated to Holland. He was arrested in Amsterdam and deported to Auschwitz where he was murdered. Caren stitches layers of meaning into her pieces. She didn’t want to use any old material to make the labels of these lost businesses, so she appealed for spare Yamulkas – or skulls caps to be donated.

So I use them because I felt that they really would fit, fit everything that they have come from Jewish people who are alive and well, and they’re a celebration, they’re a celebration of good things. So I picked them and cut them with pink and shares into these shapes and stuck them in and next to them when the label but also I made a label. It was so difficult. I did it, I dyed some material, black and stitched in white on it for, for a logo of something called ADEFA. Which is an acronym for, I can’t actually describe it because it’s very long, and it’s in German, but they were set up in 1933 and their main aim was to remove Jewish people from all areas of the fashion industry in Berlin and further and beyond in whole of Germany. And they actually did achieve their role. They, by 1938 there was barely, barely a fragment. And this is the word of Fragments, which is the name of the artwork left. I mean, people read the murdered or destitute or left the country. And on top of that, this page is open to central Europe. And, and so you see all these countries where there was a Nazi invasion and where there was huge, huge amounts of antisemitism in other countries in, in central Europe. So that was very important. And there’s one area where there’s a gap, there’s a gap and you can see, you can see what a past and Vienna where people, where Jewish people had to escape from. And also in that area, you can see Auschwitz is on there. It’s in the, on, in the Polish, the Polish word, which I can’t quite pronounce. So I’ll just say Auschwitz. So you can see that if you look closer, you can see the extra meaning to this piece. And the gap is also saying, these are the people that are forgotten that then, or here we can’t even, we don’t even know their name, but they’ve gone.

Her work is deeply moving and the reaction to it, unsurprisingly, has been supportive:

Incredibly positive from all people. I put the work up on Instagram and when I first did it, because of all these doom-mongers saying don’t do it. You know, I was scared. I was actually scared to put it up, but the actual response has been very positive and, and people are saying, yes, this is amazing. What you’re doing. Just carry on. It’s very important. And so, yeah, it’s, it’s actually been very positive. I’m not scared of doing it. I do it. And when I make an artwork, I’m not pointing a finger. I’m saying, this is what happened. This is, this is how, I mean, I’m doing it in my own way, but it’s, I’m not, I’m not accused tree I’m. I want to just do it in a very respectful way with real care and sensitivity because that’s the only way to go when you’re dealing with something as painful as this.

Which brings me right back to current events. We have been living through events over the past 18 months which have disrupted our lives completely and have meant the loss of millions of people. The pandemic is not over yet, but I have been wondering if people will find textiles a powerful and useful way to process the sorrow of this. Caren says she raises her hat to the bravery of anyone who is prepared to make work about COVID at present – she doesn’t feel ready. Deborah Stockdale though thinks it will come in time:

I think the pandemic has been a game-changer for so many people on the planet. The re-evaluation of our lifestyles, the use of, of goods and services, the way people have connected or lost, connected, lost connection with people the way that people have suffered and died and been put in conditions and it’ll help for the rest of their lives. These are all topics that artists will address in all kinds of art forms. I think one of the main things about how that’s resonated with me is the contradiction between isolation and connection, and the fact that never have most people been so isolated, but in a certain way, never have they been so connected. The fact that most people are working from home now and, you know, don’t have their usual lifestyle choices of socializing and athletics and travel, and all of those things is focused inward. And that’s a good thing in a lot of ways. And it’s also been a breathing space for wildlife and nature that was very timely. I think we appreciate those things more than ever. And they also have highlighted how fragile the planet is right now. So those are big subjects. And I think it’s something that most artists are coming to grips with either writers, artists, textile, artists, philosophers, all of these people are, are looking at a pandemic and trying to figure out what it actually means. The changes that the pandemic has brought, what that actually means to them personally. And as citizens of the universe

Thanks to Deborah Stockdale of Conflict Textiles in Northern Ireland, Judith Staley of Sewover 50, and to Carin Garfen for their insight, their courage, and for their work.

You can see images of what they have been talking about and find links to their work atwww.hapticandhue.com/listen, where you will also find a full script of this podcast and a form that gives you a chance to join the Haptic and Hue community.

It was hard to find a poem – mere words – to express some of the powerful feelings this episode has explored but after much searching, I think Mary Oliver – an American poet – comes close in this poem published in 1983 called In Blackwater Woods.

Look, the trees

are turning

their own bodies

into pillars

of light,

are giving off the rich

fragrance of cinnamon

and fulfillment,

the long tapers

of cattails

are bursting and floating away over

the blue shoulders

of the ponds,

and every pond,

no matter what its

name is, is

nameless now.

Every year

Everything

I have ever learned

in my lifetime

leads back to this: the fires

and the black river of loss

whose other side

is salvation,

whose meaning

none of us will ever know.

To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it

go,

to let it go.